Memory: The Key to Consciousness (2005)

Chapter: 9 Mechanisms of Memory

9

Mechanisms of Memory

In an espionage movie an American secret agent discovers a horrendous terrorist plot to destroy a U.S. city. With this discovery he knows how to stop the terrorists. Unfortunately, before he can tell anyone else about it, he is killed. Government scientists extract protein memory molecules from his brain and inject them into the movie’s hero. He acquires the memories from the dead agent’s brain molecules and stops the terrorists.

Sound far-fetched? Actually experiments have been done that gave some credence to this sort of scenario. The initial studies involved little flatworms called planaria that have a very primitive nervous system. These little creatures are able to regenerate after being cut up. Planaria were “trained” using electric shocks to make a certain movement. When “trained” planaria were cut up, the regenerated worms remembered the task. As it happens, planaria are cannibals. So the experimenters then ground up trained worms and fed them to untrained worms. It was reported that the untrained worms then performed the learned response.

Memory Molecules

Studies like this gave rise to the notion of “memory molecules,” the possibility that particular memories could be stored in protein molecules. This rationale led to further studies with rats, which were trained to approach a food cup. The brains of the trained rats were ground up and injected into untrained rats, who were then reported to have acquired the learned response.

Unfortunately, these dramatic experiments were not well controlled. Attempts by other laboratories to repeat these findings on planaria and rats failed completely. Indeed, a Nobel Prize–winning biochemist, hoping to identify memory molecules, devoted some 20 man-years of his laboratory’s efforts to training planaria, with complete lack of success.

Donald Stein and his students at Clark University did a critical experiment that shed much light on this puzzling situation. They trained rats in a simple task where they had to remember not to step forward in a little box (if they did, they got shocked). Brains and livers from these trained animals were ground up and injected into untrained rats. Both the brain and liver recipients showed some degree of “memory,” but the liver group did better than the brain group!

How could this happen? No one believed that memory molecules were stored in the liver. The answer is that injecting foreign protein tissue into an animal causes an immune response and other problems and can be very stressful for the animal. Stress can markedly influence activity and performance in simple learning situations. The untrained recipient animals did not “remember” the task at all; they were simply less active in the situation and didn’t step forward in the box.

Other studies involved extracting RNA from the brains of trained animals and injecting it into untrained animals. There was a bit more logic here. RNA is the messenger molecule that takes information from DNA and uses it to make proteins. So if memory involves changes in the genome, the DNA, the extracted RNA should have this new information. Unfortunately, none of

these studies could be replicated. As with the planaria, proper control conditions had not been used.

We now know that such experiments could not work. Proteins and RNA are large complex molecules and cannot pass the blood–brain barrier, a very special structure that prevents many harmful chemicals and large molecules for passing from the blood into the brain tissue. It is a kind of connective tissue lining all the blood vessels in the brain. We also know that when large foreign molecules are injected into the blood, they are generally broken down, so even if they could cross the barrier, the “memories” in the molecules would have been destroyed. Attempts to transfer memories from one brain to another by means of “memory molecules” did not work. But these studies encouraged Time magazine to suggest a solution for what to do with old college professors.

The possibility that memories could be coded in DNA and RNA raised yet again the old notion of inheriting acquired characteristics, the idea that memories could be coded by changes in the DNA of the genome as a result of experience. As far as we know, this does not happen. But the genome is very much involved in memory formation, particularly long-term memories. Studies on animals ranging from invertebrates to goldfish, rats, rabbits, and other mammals all agree that synthesis of proteins is necessary for the formation of long-term memories. The specificity of memories is in the connections among networks of neurons.

Synthesis of Proteins

Genes, DNA, are simply long chains or sequences of four different forms of a type of molecule called nucleic acids: adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), and thymine (T). A given gene may be hundreds of molecules long and has a specific sequence of these four nucleic acids. These sequences determine the protein made from the genes. Basically, all that genes do is generate proteins. RNA molecules transfer these genetic instructions from the DNA to make proteins in cells. Proteins, of course, can do many things.

Some form actual biological structures like neuronal synapses, and others serve as enzymes, controlling chemical reactions in the cell. Consequently, blocking this process of making proteins, which prevents long-term memory formation, means blocking the activity of the genes.

Many studies in which long-term memories were prevented by blocking protein synthesis involved injecting these blocking drugs systemically (that is, into the body and ultimately the bloodstream). These are powerful drugs, and they make animals sick, which might account for their effect on memory. However, infusion of these drugs into places in the brain where long-term memories are being formed can also prevent the memories from being established. One of the present authors (RFT) infused such a drug, actinomycin, into the cerebellar nucleus in rabbits, where long-term memory for the learned eye-blink response is formed. This procedure completely prevented learning of the eye-blink response. However, if the drug was infused in this location in trained animals, it had no effect. It only prevented learning of the conditioned response. Interestingly, a new protein was formed in this region as the rabbits learned the task. This protein is an enzyme that is normally involved in cell division. Since neurons do not divide after birth, perhaps such enzymes do other things in neurons.

One possibility of why gene expression—making proteins—is necessary for the formation of long-term memories is that new structures must be formed in the neurons to store the memories. Synapses, the connections between neurons, are an obvious candidate for new structures in neurons.

Synapses and Memory

The number of possible synaptic connections among the neurons in a single human brain may be larger than the total number of atomic particles in the known universe! This probability calculation assumes that all of the connections are random, and indeed many do seem to begin at random in the developing brain. But the

actual number of synaptic connections in a typical adult human brain, is of course, very much less, roughly a quadrillion (1 followed by 15 zeros), still an impressive number.

The human genome contains a great deal of information, perhaps the equivalent of an encyclopedia set. However, the information capacity of the genome is orders of magnitude less than the number of synaptic connections between the neurons in the brain. So these connections cannot all be determined genetically. Instead, experience must shape the patterns of nerve cell connections in the developing brain. To be sure, the organization of major structures and areas of the brain and their patterns of interconnections are determined genetically. It is at the finer grain, the details of synaptic connections on the dendrites of neurons, where experience comes into play. In Chapter 3 it was noted that brain synapses increase dramatically in number over the first few years of life, the same period when much of our learning occurs. This is particularly true for the brain systems critically involved in memory formation, the cerebral cortex, the hippocampus, and the cerebellum. Synapses form, alter, and disappear throughout life.

We have a good understanding of how the patterns of synaptic connections form in the primary visual cortex. The axons from the visual thalamus conveying information to the cortex terminate on primary receiving neurons. Initially, each neuron has equal synaptic connections of input from each eye. Then as a result of visual experience after birth, input synapses from one eye or the other dies away, so each of these primary neurons is activated by only one eye or the other.

The key is visual experience. Covering one eye results in all the input from that eye dieing away from all the primary neurons, so the eye, actually the visual cortex, becomes blind. Seeing is necessary for normal development of the visual cortex. But how? It turns out that nerve cell activity, spike discharges, or action potentials are necessary. When seeing the world, the neurons projecting information from the eye to the visual cortex are very active, conveying many spike discharges per second to the primary

receiving neurons in the visual cortex. Covering the eye prevents these action potentials from occurring. Suppose both eyes are functioning normally and the neurons projecting information from one eye to the cortex are inactivated, perhaps by infusing a drug that reversibly shuts down neurons, preventing them from generating spike discharges. The result is the same as if we cover one eye. The development and maintenance of the normal visual system is dependent on normal activity of the neurons in the visual brain.

Recall the rich rat–poor rat studies. A normal stimulating environment is necessary for normal development of the cerebral cortex. A poor environment results in many fewer synaptic connections. A similar type of process is thought to occur in the brain when we learn.

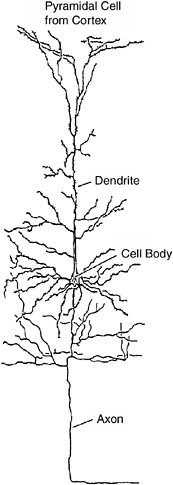

A typical neuron in the cerebral cortex is shown in Figure 9-1, the same one shown in Chapter 3. The dendrites receive connections from hundreds or thousands of other neurons via axons forming synaptic connections on these dendrites. Each little bump or spine on each dendrite is a synaptic connection from another nerve cell axon terminal. As you can see, the dendrites are covered with these little spine synapses. Rich rats have many more dendritic spine synapses than poor rats. Indeed, people with college degrees have more spine synapses on dendrites in certain areas of the cortex than do people with only high school degrees, who in turn have more synapses than people who did not finish high school. The memory trace, the physical basis of memory storage in the brain, may simply be more synapses. But this begs many questions—for example, how and where are they formed? We return to these questions later.

Does the proliferation of cortical synapses in the rich rat and well-educated human reflect specific memories or simply more general factors like intelligence and well-being? It has been difficult to answer this question, in part because for most kinds of memories it is not known exactly where they are stored in the brain. Indeed, some neuroscientists think that complex memories like those of our own experiences (declarative memory) may

FIGURE 9-1 The dendrites of a neuron are covered with thousands of little bumps or spines, each of which is a synapse receiving information from another neuron.

be stored in widely distributed networks of neurons, probably in the cerebral cortex. The jury is still out on this question. But there are a few examples of where particular memories are thought to be stored in particular places in the brain.

Mark Rozenzweig of the University of California, Berkeley, and William Greenough of the University of Illinois pioneered the rich rat–poor rat studies. The first studies simply showed that

the cerebral cortex was thicker in the rich rats. Greenough showed that this was due primarily to the growth of more synapses and more nonneural supporting cells called glia. (But remember that the rich rats were really normal rats, and the poor rats had fewer than normal numbers of synapses and glia.)

Greenough and his associates have provided a clear example of where a type of memory may be localized. When rats are trained to reach with a forepaw through a small hole in a piece of clear plastic to retrieve a bit of food, the region of the cerebral cortex that represents movements of the forepaw becomes critically engaged. After the animals have been trained, damage to this small region markedly impairs their performance in this task. As animals learn the task (no damage) there is a dramatic increased growth of synaptic connections among the neurons in this region.

Pavlovian conditioning of the eye-blink response provides an example of associative memory (see Chapter 7). As noted one of the present authors (RFT) and his many associates have been able to localize the basic memory trace for this form of associative learning to a particular place in the brain, a group of neurons in a cerebellar nucleus. Lesions of this small region completely and permanently abolished the learned eye-blink performance.

Studies by Jeffrey Kleim at the University of Lethbridge and John Freeman at the University of Iowa demonstrated that there is a dramatic increase in the number of excitatory synapses in this localized region of the cerebellum as a result of learning the conditioned eye-blink response. This particular memory appears to be stored by the increased number of synapses in this nucleus.

New Neurons and Memory

For a long time it was believed that people are born with the full compliment of neurons in their brains and that no neurons are formed afterward. We now know this is not the case. New neurons are formed in some limited regions in the brain throughout life. But they are not formed from other neurons. Once formed, neurons never divide. Instead new neurons are formed from stem

cells adjacent to brain tissue. Stem cells do divide and in fact can form many different tissue cell types. Some stem cells migrate into brain tissue, becoming neurons. This process is now well established for a region of the hippocampus. Indeed, it is estimated that up to 5,000 new neurons form every day in the rat hippocampus! Pioneering work establishing this heresy was done by Fred Gage at the University of California, San Diego, and Elizabeth Gould at Princeton University. However, there is considerable disagreement about the extent to which new neurons form in regions of the cerebral cortex. In the hippocampus it appears that new neurons may actually become functional in circuits of neurons.

In a series of elegant experiments, Tracey Shors at Rutgers University showed that new neurons in the hippocampus play a critical role in learning and memory. She used eye-blink conditioning as her basic procedure. In the standard procedure, a tone is presented that lasts about half a second. At the end of the tone an air puff is delivered to the eye. Initially the air puff, of course, elicits an eye-blink response, but the tone does not. After repeated presentations of the tone and air puff, the tone comes to elicit the eye blink, a conditioned response.

There is another procedure, initially developed by Pavlov, called trace conditioning, in which the tone stimulus ends before the air puff begins. This trace interval can extend as long as a second or more and learning can still occur. Pavlov called it a trace procedure because a trace of the tone must be maintained in the brain to become associated with the occurrence of the air puff. The cerebellum is the essential structure for the standard procedure, as we saw earlier. However, both the cerebellum and the hippocampus are critical for trace learning.

Remember HM? After hippocampal surgery he was unable to learn and remember his own new experiences and could not remember events that occurred in the year or so before his surgery. But his memory of his experiences and knowledge before that time was normal. Exactly the same is true for animals (rabbits, rats) trained in trace eye-blink conditioning. If the hippocampus is re-

moved before training, the animals are unable to learn trace eye-blink conditioning, but they have no trouble learning the standard procedure. If the hippocampus is removed immediately after training, the trace memory is abolished, but if it is removed a week or two after training, the trace memory remains intact (unlike the hippocampus, appropriate cerebellar damage always completely prevents learning and abolishes the memory for both trace and standard procedures).

Robert Clark and Larry Squire at the University of California, San Diego, worked with human patients with severe amnesia due to hippocampal damage similar to that of HM. These patients are completely unable to learn the trace eye-blink conditioning procedure with a trace interval of one second. But they learn the standard procedure (not hippocampal-dependent) normally. Some normal humans have difficulty learning the trace procedure, and others do not. Remarkably, those people who were aware that the tone would be followed a second later by an air puff to the eye learned well, and those who were unaware of what was happening had difficulty learning. You may remember that conscious awareness is a key feature of declarative memory. So it would appear that trace conditioning provides a simple model of declarative memory in both humans and animals.

Returning to the work of Tracey Shors, she trained rats in eye-blink conditioning using both the trace and standard procedures. Remember that removing the hippocampal prevents trace but not standard learning in rats. She discovered a substantial increase in new neurons in the hippocampus in rats that had learned the trace procedure but no increase in rats that learned the standard procedure. In a dramatic follow-up study she injected rats with a chemical that prevents cell division, including the formation of new neurons. Treated rats were unable to learn the trace procedure but learned the delay procedure normally. It seems that formation of new neurons in the hippocampus was essential for trace learning. This raises the intriguing possibility that other forms of new learning also may involve the formation of new neurons.

Plasticity of the Cerebral Cortex and Memory

Suppose you had a serious accident and lost a finger. What would happen to the brain area that represents your finger? The body skin surface is represented precisely on a region of the cerebral cortex called the somatic sensory area. We will refer to it here as the skin sensory area. Representation of the body surface on the cortex is indeed precise but very distorted and is determined by use and sensitivity. The more sensitive the skin is to touch, as in the fingers, the greater the amount of cortex that is devoted to it. Indeed, judging by the area of cortex devoted to each area of the body, humans are largely fingers, lips, and tongue. Each finger has its own little area of representation in the cortex.

To return to the hypothetical accident, after you lost your finger, the area of cortex representing this finger gradually shrunk. The areas representing adjacent fingers spread over the missing finger area and gradually took it over. Michael Merzenich and his associates at the University of California, San Francisco, have demonstrated this in a series of elegant experiments with monkeys. They also showed that if a finger was stimulated for a long period of time, perhaps by a vibrator, the skin cortical area for the finger expanded and spread into adjoining finger areas.

A dramatic example of this “takeover” of skin sensory cortex has been described for some patients with arm amputations. Long after the amputation, the patient may experience sensations of the nonexistent hand being touched when a region of his face on the side of the amputation is touched! It would seem that the face area of the skin cortex adjacent to the area for the missing arm has “taken over” this area. But the sensation is still of the hand being touched, not the face. By the same token, if we were to electrically stimulate the missing arm area of the skin cortex, the sensation would be localized to the missing arm.

Musicians provide a ready source of people with extreme overuse of their fingers. This is particularly so for violinist. The little finger of the left hand (for a right-handed violinist) works particularly hard. The area of representation of the left little fin-

ger on the skin sensory cortex is relatively small. In brain imaging studies, the extent of the left little finger representation in the skin cortex was determined for string instrument players. As expected, there was a major expansion of the left little finger area in the cortex. Indeed, the degree of expansion of this left little finger area increased in close association with years of experience as a violinist!

Regions of the cerebral cortex of adult humans can expand and contract with experience just as they do in an infant’s brain as it grows and develops. It is plastic and dependent on experience throughout life. Part of this is probably due to changes in the number of synapses, but other kinds of processes occur as well.

Although it seems possible that growth of new synapses and even new neurons could be the physical basis of the memory trace for all forms of memory, this is known with some degree of certainty for only a few types of learning. But making new synapses takes time and new memories seem to be formed rapidly. As we experience events the initial memories are formed.

The First Stage in Memory Formation

When you experience any event, from items you hear on the morning news, to something a friend or loved one says, to a dream, you experience it only once, yet you remember it. If the event is not special, you do not rehearse it—keep thinking about it—but it remains to some degree in your memory for some time. Something must happen very rapidly in the neurons of the brain, in milliseconds to seconds, to form this initial memory. And whatever this process is, it must persist at least for days.

Long-Term Potentiation and Memory

Two scientists working in Oslo, Norway, in the laboratory of Per Andersen discovered the phenomenon of long-term potentiation (LTP). Tim Bliss, from England, and Terje Lømo, from Norway, were electrically stimulating a nerve pathway projecting to the

hippocampus in an anesthetized rabbit. After giving a brief train of stimuli at a rate of 100 per second to this pathway for one second, they found to their astonishment that the neurons in the hippocampus activated by this pathway increased their responses substantially and that the increase lasted for hours—for the duration of the experiment. The neuron response was potentiated following brief high-frequency stimulation. This finding assumed particular importance because the hippocampus is critically involved in experiential or declarative memory.

We learned earlier that the hippocampus is not the repository of permanent long-term memories. HM can remember his life up to a few years before his surgery; monkeys remember up to about two months before hippocampal removal. Rats and rabbits remember events up to a week or two before surgery. Hippocampal-dependent memories are time limited. The hippocampus acts like a buffer memory system. It is necessary to hold memories for some period of time but not permanently. The final repository for long-term declarative memories is thjought to be among the neurons of the cerebral cortex, but the data are not clear.

In freely moving animals with electrodes permanently implanted in their brains, LTP can be measured for days or weeks. In rats, at least, LTP decays slowly over weeks. Neurons in the cerebral cortex also show LTP, and this may be a way that memories are initially stored in the cortex.

The mechanisms responsible for LTP in hippocampal neurons are well understood (see Box 9-1). The key actor is the chemical neurotransmitter glutamate. Molecules of glutamate are released from the terminals of the nerves that connect to (synapse on) hippocampal neurons. Glutamate, incidentally, is the workhorse excitatory transmitter for neurons in the brain. It increases the excitability of neurons and appears to be the key “memory” neurotransmitter wherever memory processes occur, in the hippocampus, cerebral cortex, and cerebellum.

Much of our understanding of the mechanism of LTP has come from a special procedure developed in Per Andersen’s laboratory in Oslo—the hippocampal slice. Animals, usually rats or

|

BOX 9-1 In hippocampal neurons, glutamate acts on several receptors on the neuron cell membrane at synapses. Two receptor molecules are critical for LTP: AMPA and NMDA (abbreviations for very long clinical names). Under normal circumstances where the pathway to the hippocampus is active only a little, AMPA receptors are activated and hippocampal neurons respond in a normal not a potentiated manner. However, when the pathway is stimulated at high frequency, the NMDA receptors are also activated. They in turn permit calcium ions (charged atoms) to enter the neuron. Calcium activates biochemical processes that result in more AMPA receptors becoming responsive to glutamate. Hence, the next time glutamate molecules act on the AMPA receptors, the activity of the neuron will be greatly increased. So the basic mechanism is an increase in the AMPA receptor response to glutamate in hippocampal neurons. How it was discovered that high-frequency activation of the NMDA receptors causes them to become active, to pass calcium ions into the neuron, is a fascinating story. With normal low-frequency activation of the pathway, glutamate attaches to the NMDA receptors, but it is not enough to activate them. Why? Because there is another kind of ion, magnesium ions, in the calcium channels of the NMDA receptors that blocks the channels. If the pathway is now strongly activated by high-frequency stimulation, the magnesium ions are removed from the NMDA channels in the neuron permitting calcium to enter. This in turn increases the number of functional AMPA receptors, resulting in LTP. The actual mechanism causing the magnesium ions to be removed from the NMDA channels is a change in the neuron membrane voltage level. It becomes more positively charged or depolarized. This removes the magnesium ions from the channels. |

mice, are anesthetized and painlessly killed; then the hippocampus is removed from the brain and cut into slices. The anatomy of the hippocampus is arranged so that each slice contains the key circuitry of the hippocampus, from input to output. The slice can be maintained alive and functional for many hours in its nutrient bath. Under these conditions the complete environment of the slice can be fully controlled, which is simply not possible when the hippocampus is in the brain. LTP can easily be induced in the hippocampal slice.

Some years ago a young neuroscientist anmed Timothy Teyler spent a year in Per Andersen’s laboratory learning the slice technique and its use to study LTP. He then joined one of the present authors (RFT) at Harvard, where he set up his slice laboratory and taught several American scientists the method. Another young neuroscientist, Philip Schwartzkroin, also spent a year in Oslo and brought the method to the West Coast at the University of Washington in Seattle.

The form of LTP we have described is NMDA-dependent LTP (see Box 9-1). The NMDA receptor is one type of receptor for the chemical transmitter substance glutamate. A great deal is known about the biochemistry of the NMDA receptor. For example, substances have been developed that completely block its functions. One such drug, APV for short, completely blocks the development of LTP and has been used to study the role of hippocampal LTP in memory. In a pioneering study, Gary Lynch and Michel Baudry, at the University of California, Irvine, and Richard Morris, from Scotland, infused APV in the hippocampus of rats while they were trying to learn a maze. This completely prevented learning, suggesting that LTP in the hippocampus was key for this form of memory.

There are other forms of LTP as well. Teyler discovered a kind of LTP in the hippocampus that does not depend on NMDA receptors. Instead, calcium is moved into the neurons by channels that are activated when the neuron cell membrane becomes depolarized (voltage becomes positively charged). These are called voltage-gated channels. Teyler found that this voltage-gated form of LTP is widely present in neurons in the cerebral cortex and may be critical for the formation of long-term memories.

Other kinds of changes not involving synapses may also serve to code memories. John Disterhoft and his associates at Northwestern University discovered that changes in neurons in the hippocampus occurred within the neurons themselves, following eye-blink conditioning in rabbits. These changes did not involve synapses but made the neurons more responsive to synaptic activation.

A Tale of Snails, Flies, Mice, and Memory

Evolution is exceedingly conservative. If something works, it persists. The way a nerve cell sends information out its axon from the cell body to the synaptic terminals to act on other nerve or muscle cells—the action potential—is basically the same in all animals, from the most primitive animals with neurons, the jelly-fish, to humans. Perhaps many other ways of conveying information were tried at the beginning of multicellular creatures. But once the action potential appeared, it worked so well that it was kept throughout the next billion or so years of evolution. The action potential, incidentally, is simply a rapid, localized change in the voltage across the neuron cell membrane that begins at the cell body and travels out the axon.

The speed of the action potential is slow relative to the speed of electricity, from about 1 mile per hour to something under 200 miles per hour. But distances are short, at least in the brain.

Habituation

The process of habituation—a decrease in response to repeated stimulation—is a clear case of conservation in evolution. To take a human example, if you hear a sudden, loud sound, you will be startled and jump briefly. If the sound is repeated often, you will stop being startled; you will habituate. Suppose you are then given an unexpected and unpleasant or fearful stimulus, perhaps an electric shock. The next time you hear the sound you will be startled, perhaps even more than you were initially. You have become sensitized.

The mechanism underlying this rapid or short-term habituation appears to be the same in all animals with nervous systems from simple invertebrates to mammals. The basic process is synaptic depression as shown in work by Eric Kandel, one of the present authors (RFT), and others. As a result of repeated activation of nerve axons, the amount of chemical neurotransmitter released from the axon terminals decreases. The chemical neurotransmitter molecules in the nerve axon terminal become less

available for release. They are not simply used up. Following a strong stimulus like a shock, they now release much more transmitter than they did to the first presentation of the habituating stimulus. The circuit becomes sensitized.

Rats are startled by sudden loud sounds just as people are. But not all the synapses in the circuit from hearing the sound to jumping habituate. Instead, habituation occurs primarily at the synapses connecting the sensory system neurons, here the auditory system, to the motor system that controls the startle response. The same appears to be true for humans. Indeed, the same is true in simple invertebrates where the sensory neuron connects directly to the motor neuron.

Some years ago, one of the present authors (RFT), together with a graduate student, Philip Groves, developed a “dual-process” theory of habituation. The basic notion is that stimuli that elicit responses (like startle to a loud sound) induce both habituation processes in synapses and also sensitizing processes, and these yield the final behavior. This simple theory was able to predict a wide range of behaviors.

So the basic mechanism for habituation, at least for relatively short-term habituation, is well understood, perhaps the best-understood example of a “memory trace”: synaptic depression. However, even for this simple form of learning, the mechanisms underlying long-term habituation occurring over days or weeks are not well understood.

Long-Term Memory

Snails

Eric Kandel and his many associates at Columbia University have used a relatively simple invertebrate, the sea snail Aplysia as an animal model to study the basic processes of memory. The nervous system of this animal has only a few thousand neurons, many of which are large and can be identified individually. Kandel focused on a simple circuit where a sensory neuron conveying information about touch connects directly to a motor neuron that

activates a muscle. This piece of the nervous system is very hardy. It can be removed from the animal and kept alive in a dish. In fact, a tissue culture can be prepared with just the sensory neurons synapsing on the motor neurons. This system shows habituation—that is the response of the motor neurons to repeated stimulation of the sensory neurons decreases.

Strong and persistent activation of this system can result in long-lasting sensitization, an increase in synaptic transmission that can last for hours. Actually, the best way of inducing this long-lasting sensitization is by adding a chemical neurotransmitter, serotonin, to the system. This method provides a simple model of persistent use–dependent increase in synaptic activation, which they use as a simplified model of long-term memory.

Eric Kandel and his associates analyzed the biochemical processes that occur in neurons as a result of long-term sensitization in great detail. Indeed, Eric was awarded a Nobel Prize in 2000 in part for this work. A particular molecule in the neuron is critical for this process of long-term sensitization, CREB (cAMP responsive element binding proteins). When strong and persisting synaptic activation occurs on a neuron, a chemical inside the neuron called cAMP becomes activated and in turn activates CREB. CREB now acts on the DNA of the genome to change the expression of certain genes. Among other things, expression of these genes can result in structural changes at synapses and even the growth of new synapses.

This work on CREB was an elegant analysis of how long-term memories might be formed in neurons, but the model system was after all a rather simple invertebrate nervous system. How general might this possibility be? As it happens, CREB has been implicated in memory function in flies and mice, as well as Aplysia, and therefore must also be involved in memory formation in humans, or so we think.

Flies

It used to be thought that flies lived from birth to death without ever learning anything. Now we know better. The fly actually has

a rather complex little “brain,” as do bees, ants, and other higher insects. A geneticist at the California Institute of Technology, Seymour Benzer, decided to explore the genetic basis of complex traits like memory using the fruit fly, Drosophilia melanogaster. You have probably seen these little flies on fruit that is becoming spoiled. They die of old age about a month after they are hatched, making them particularly useful for genetic studies. Benzer treated the animals with procedures that induced mutation in the genes of the parents, resulting in mutant offspring. Many of these mutants had clear structural abnormalities, for example, different colored eyes.

Chip Quinn, a young neuroscientist working in Benzer’s laboratory, developed a method for teaching the flies to discriminate odors, by pairing certain odors with electric shock, an example of Pavlovian conditioning. In these initial studies Quinn and a young scientist from Israel, Yadin Dudai, discovered a mutant they christened “dunce” that was unable to learn the odor task.

Tim Tully developed an ingenious procedure by which he could train large numbers of flies at the same time. He placed the flies in a central chamber with two side chambers, each having a different odor. One side chamber odor was paired with electric shock and the other was not. After several trials of training, the flies were placed in a new set of chambers with the same odors as before. Most of the flies congregated in the side chamber with the odor not associated with shock.

An important outcome of this work was the discovery that flies, like mammals, appear to have both short- and long-term forms of memory, at least for this olfactory task. One mutant called “linotte” could not learn the task at all. Dunce and “rutabaga” did show some learning but forgot immediately; they could not even form short-term memories. On the other hand, “amnesiac” and some other mutants were able to form short-term memories but could not form “long-term” memories (a relative term since the flies live for only a month).

A key point in this work is that the conversion from short-term memory to longer-term memory involves CREB. If CREB

function is impaired, so is long-term memory. On the other hand, in a genetically altered fly with amplified CREB function, the fly forms long-term memories more rapidly than a normal fly.

Mice

An extraordinary new genetic approach to the study of memory in mammals is the gene “knockout” technology. It is possible to block the functioning of a particular gene by manipulating the DNA. The technical details are rather complicated, but the end result is mice with a particular gene being nonfunctional. Actually, it is even possible to create a mouse whose gene functions normally until the animal is given a certain chemical. The animal’s genome has been so modified that this chemical temporarily shuts down (or turns on) the functioning of the gene.

This approach to the study of memory in mammals was pioneered in the laboratory of Susumu Tonegawa at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Tonegawa had earlier won a Nobel Prize for his work in immunology and now focuses on memory. A young scientist in his laboratory, Alcino Silva, prepared a mutant mouse with a gene for CREB deleted. These animals showed markedly impaired ability to form long-term memories in several types of learning situations, including learned fear and a form of maze learning. In normal mice, hippocampal damage also causes marked impairment in these learning situations.

One other set of discoveries brings the story full circle. LTP is easily induced in the hippocampus, as noted earlier. Some researchers have argued that LTP has two phases, a short time period of one to two hours after the one second high-frequency stimulation and a long time period of more than seven hours after stimulation. It is reported that inhibiting protein synthesis does not affect short-duration LTP but prevents long-duration LTP, as is true for the formation of long-term memories. CREB knockout mice do not develop the long-duration LTP.

Space, Place, LTP, and the Hippocampus

Rats and mice live in a world that is made up of complex spaces, a mazelike world. They have developed impressive abilities to construct internal representations of the spatial features of their worlds, and in recent years a great deal has been learned about how this is done in the brain.

One of the most intriguing discoveries about the hippocampus was the identification of “place” cells by John O’Keefe, working in London, as noted briefly in our discussion of dreaming. He was recording the activity of single neurons in regions of the hippocampus in freely moving rats. He noted that, when the animal was traveling along a runway, a given neuron might start firing only when the rats moved past a particular place on the runway. Other cells responded to other particular places on the runway. It takes only a few place cells to “fill” any environment. That is, each cell responds to some part of the spatial environment that the animal is in and perhaps 15 cells will code the entire particular environment.

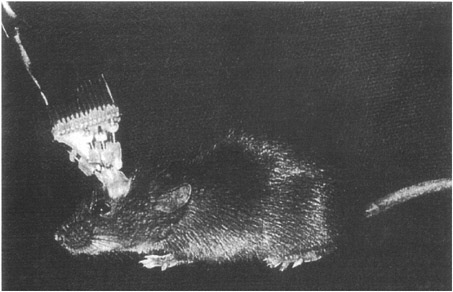

Perhaps the most extraordinary recent studies on hippocampus place cells have been done by Bruce McNaughton and Carol Barnes at the University of Arizona, and Matt Wilson (now at MIT). They developed a system for recording the activity of many single hippocampal neurons at the same times, as many as 120, using sets of movable microelectrodes implanted in the animal’s head (see Figure 9-2).

When the animal is in a particular environment, perhaps on the floor of a square box, different neurons in the hippocampus respond (fire action potentials) at different places on the floor of the box as the animal moves to these places. The activities of those neurons that respond to the different places in the box actually form a “map” of the box floor. By looking at the patterns of activity of these neurons at any given moment in time the experimenter can accurately tell exactly where the animal is in the box.

Are place cells learned? In rodents they appear to form rapidly, almost instantaneously, when the animal is put into a new environment. This contrasts markedly with the many trials and

FIGURE 9-2 A mouse with an implanted microdrive to record simultaneously from a number of single neurons in the hippocampus while the animal is freely moving about.

long periods of time it takes a rodent to learn a complex maze. The relationship between place cells, learning, and memory is unclear, but hippocampal lesions do impair spatial learning and memory performance in rodents. A common hypothesis concerning place fields is that they are initially formed by a process like LTP.

Susumu Tonegawa, Matt Wilson, and their collaborators at MIT developed a most interesting mouse whose gene that makes a subunit of the glutamate NMDA receptor is knocked out—that is, deleted from its genome. Specifically, they knocked out this gene but only in one particular region of the mouse’s hippocampus. They showed that in this animal it was not possible to induce LTP in this region, even though LTP induction was normal in another region of its hippocampus. The NMDA receptor is necessary for the induction of LTP in this region. Furthermore, these animals were markedly impaired in a spatial maze-learning task. Accordingly, there were abnormalities in the place field organiza-

tion of this region. The place fields in normal mice are localized to particular places in the environments. The knockout mice showed much larger place fields with less discrete organization.

Conclusion

This research on the possible mechanism of memory suggests a working hypothesis about how memories are formed and stored in the brain: A learning experience induces rapid functional changes in neurons such as LTP. Over a period of minutes to hours and days, a complex series of events involving CREB and other biochemical processes acting via the DNA results in changes in the structures of synapses, the growth of new synapses, and other changes in the neurons resulting in the establishment of long-term memories. But we hasten to add that for most forms of memory we do not actually know where in the brain these memories are formed and stored or the actual molecular/synaptic mechanisms involved.

Processes like LTP, synaptic growth, and other changes in neuron excitability may indeed occur when memories are formed. Will our knowledge of these processes enable us to understand memory storage in the brain? The answer is clearly no. All these changes do is alter the transmission of information at neurons where they occur. The nature of the actual memories so coded is determined by the particular neural circuits in the brain that form the memories. The memory for the meaning of the word “tomato” is not in molecules or at particular synapses; it is embodied in a complex neural network embedded in larger complex networks that can code and store the meanings of words.

Molecular genetic analysis may someday tell us the nature of the mechanisms of memory storage in the brain, but it can never tell us what the memories are. Only a detailed characterization of the neural circuits that code, store, and retrieve memories can do this. We are still a long way from this level of understanding of memory.