Memory: The Key to Consciousness (2005)

Chapter: 5 Amnesia

5

Amnesia

Sudden memory loss has been an important plot element in many works of fiction. The film Memento, released in 2001, features a protagonist named Lenny who suffers brain damage in an assault. He is shown as being mentally normal in many ways: His language production and comprehension are normal, he has retained perceptual skills and knowledge (he knows the names of objects and what they are for), his social behavior is appropriate, and he remembers his personal past that preceded the brain damage. What Lenny has lost is his ability to form new, durable memories. He cannot remember the previous day’s experience and he has to write notes to (sometimes onto) himself if he is to remember his plans, intentions, and recent experiences.

The Majestic is another movie that appeared about the same time as Memento. Its central character also suffers a head injury, this time in a car accident. Like Lenny, he retains his perceptual memory, language, and habits of social behavior but, unlike

Lenny, is still able to form and retain new memories. The problem is that he has lost most memories of his personal past.

Neither film is science fiction. Memento presents a generally accurate depiction of severe anterograde amnesia. The Majestic depicts a very severe case of retrograde amnesia, although in a somewhat improbable way, since retrograde amnesia caused by brain damage is usually accompanied by some anterograde amnesia. In this chapter we examine these two kinds of amnesia in detail, along with a discussion of other kinds of amnesia produced by disruption of the normal state or functioning of the brain.

Temporal Lobe Amnesia

Lenny’s memory problems are very much like those of patient HM, described in Chapter 1. HM’s story began in 1953 when a neurosurgeon named William Scoville performed a series of surgeries on a group of mentally disturbed patients in an attempt to treat severe and intractable psychotic behavior as well as on one nonpsychotic individual with severe epilepsy whose seizures were becoming more frequent and not controllable with medication. The surgical procedure consisted of making two holes in the forehead above the eyes, inserting a surgical tool to move the frontal lobes out of the way, and then removing brain tissue from the medial temporal lobes, including the hippocampus and amygdalae.

Scoville reported improvement in some of psychotic patients, but he also reported that the procedure had a terrible side effect for one psychotic patient and for the epileptic patient—“grave loss of recent memory,” or what we have referred to as severe anterograde amnesia. These two patients (one of them HM) were now severely limited in their ability to form new (postoperative) memories of everyday events, and performed very poorly on tests of episodic learning and memory. The two patients did show some retrograde amnesia but it was relatively mild compared to the anterograde amnesia. Their abilities to recognize objects and their language skills were intact.

The memory problems of the epileptic patient HM have been studied for 50 years now, and many other similar cases have been identified since the 1950s. The surgical procedure that HM experienced was discontinued when the adverse side effects were discovered, but other cases of temporal lobe amnesiacs have occurred as a result of brain damage from accidents, encephalitis, or conditions that interrupt blood supply to the brain. Under some conditions, these kinds of events damage hippocampal tissue without much damage to other areas.

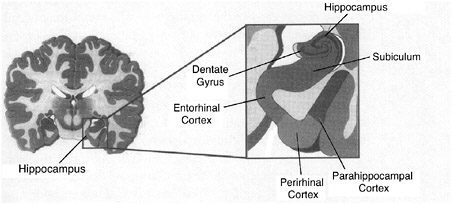

The findings of these studies have had an enormous impact on memory theory. To start with, they drew attention to the possible importance of the hippocampus for learning and memory. Figure 5-1 is a coronal (frontal cross-section) view of the hippocampus in the left hemisphere of the brain. It is about eight centimeters long and is located on the inner (folded) part of the temporal lobe in both brain hemispheres. (“Hippocampus” is Greek for “seahorse.” With a little imagination, you can see why this brain region is so named by looking at the structures in Figure 5-1.)

A second major finding of temporal lobe amnesia research is that hippocampal damage impairs some kinds of learning and

FIGURE 5-1 The hippocampal complex in the temporal lobes of the human brain.

memory functions while leaving others unaffected. For example, HM’s memory has been described as consisting of the following sets of spared functions:

-

Intact immediate or short-term memory (his memory span is in the normal range).

-

Intact general mental functioning (his IQ did not decrease following the surgery).

-

Intact ability to learn some new motor skills.

-

Preservation of language skills.

-

Preservation of perceptual skills (recognition of objects and their meaning).

-

Intact implicit memory and priming (he is faster at pronouncing a word if he has seen or heard the word earlier).

-

Retention of most personal or autobiographical memory, but with some loss of memory for events a few years before the surgery (time-limited retrograde amnesia).

HM’s main memory problem is a severe anterograde amnesia, based on extreme difficulty in creating new episodic memories. He is described as being unable to remember peoples’ names despite being introduced to them repeatedly, as having little memory for news events, and as not knowing the meanings of words that started appearing in everyday language long after 1954 (jacuzzi, frisbee, mousepad, slamdunk). This would seem to indicate that his semantic memory has also been affected. His performance on the battery of memory tests making up the Wechsler Memory Scale is very poor (a memory quotient of 64, compared to his IQ of 110). Many of the tests that make up the Wechsler Memory Scale are tests of explicit episodic memory in which new information must be retained in the face of distractions and delays.

The sparing of implicit learning abilities in temporal lobe amnesics was an important discovery. Temporal lobe amnesics do have the ability to store and retain new information as long as they are tested in ways that do not require explicit, conscious attempts at memory retrieval. This has been shown in studies of

repetition priming. For example, when normal research subjects read a list of common words, pronouncing each one as quickly as possible, and then at some later time are given a second test with a word list that includes words from the original list as well as new words, they will pronounce the repeated words faster than the new words in the second test. (As we saw in Chapter 2, this can happen over intervals of several weeks or more between the first and second tests.) The same is true of temporal lobe amnesics. Some studies have found that these patients show as much priming (that is, benefit from a previous experience) as normal control subjects. Clearly, for there to be a priming effect in this experimental task, a subject must retain information from the first experience with the words. These same studies also show that temporal lobe amnesics have poor memory for the original word list when this memory is tested by an explicit test procedure (“Recall as many of the words as you can from the list you saw yesterday”). These combined results are referred to as the dissociation of explicit and implicit memory systems.

The anterograde amnesia that temporal lobe patients display is often described as a “complete inability” to remember, and their implicit memories are described as being “normal.” but these descriptions appear to be somewhat exaggerated. HM, for example, can perform reasonably well in a memory experiment if he is given ample study time or many learning trials, and not all studies find that implicit learning is really as good in patients as in control subjects. Nevertheless, temporal lobe damage that includes the hippocampus and adjacent structures reliably leads to severe deficits of some kinds of memory, with a relative sparing of other kinds of memory. A relatively recent example of this involved three children who suffered early hippocampal damage. All of them seem like patient HM in that their episodic memory measured by explicit tests is very poor, but all of them had acquired language, world knowledge, and schooling. Some researchers take this to mean that “fact memory” formation does not require the hippocampus; only episodic memories of personal experience do.

Animal Models of Amnesia

In the years since his case was described, numerous unsuccessful attempts were made to re-create HM’s massive memory impairment in animal models. It was only in 1978 that Mortimer Mishkin, working at the National Institute of Mental Health in Bethesda, Maryland, reported success. He worked with Rhesus monkeys, a popular animal model of human brain function. Although this animal’s brain is considerably smaller than the human brain, it has a similar organization of the cerebral cortex and other higher brain regions. The Rhesus monkey has color vision that is identical to human color vision, and visual areas (30 or more!) in the cerebral cortex that are very similar to human visual areas. Indeed, humans and Rhesus monkeys are only separated by some 20 million years or so of evolution. The key to Mishkin’s success came in the behavioral task he set for the monkeys. It is called delayed non-matching-to-sample and is very simple. The animal is first presented with an object (see Figure 5-2). He moves the object and obtains a reward of a peanut or raisin. He is then presented with two objects, the one he has seen before and a new object. If he moves the new object, he gets the reward, but if he moves the old object, he does not. New objects are used for each test, so the animal cannot form long-term memories of the objects in order to solve the problem. A delay is introduced between presentation of the single object and presentation of the two objects. Once the monkey has learned to do this task, he can remember the initial object for delays of many minutes. Monkeys greatly enjoy this task. As with humans, they like novelty and new experiences. Interestingly, if we reversed the task and required the monkey to choose the old object instead of the new one, it would take him much longer to learn the task.

Mishkin made extensive brain lesions in the medial temporal lobe on both sides that included the hippocampus and closely adjacent brain regions. These animals were markedly impaired on the tasks for delays beyond a minute or so; however, they performed normally for very short delays, showing that their percep-

tions of the objects were normal. This is a simple form of recognition memory; rather than remembering where the object is, the monkey must remember what it is. This task seems to capture at least some aspects of HM’s memory impairment.

Following Mishkin’s discovery, other researchers repeated and extended this work, most notably Larry Squire and Stuart Zola at the University of California at San Diego. We now know that the hippocampus is critically involved, but closely adjacent regions of the cerebral cortex are also involved; the more of these that are damaged, the worse the impairment in the memory, in both monkeys and humans.

Where Are Permanent Memories Stored?

Mishkin’s monkeys have something else in common with human temporal lobe amnesics: Damage to the hippocampal area does not result in the loss of all knowledge and skills that existed prior to the damage. That is, there is no massive retrograde amnesia. As Squire and Zola showed, these animals are impaired in remembering only things they had learned up to about two months prior to the brain lesion. As we’ve seen, patient HM shows a time-limited retrograde amnesia and no loss of language skills or IQ. All of this seems to say that long-term permanent memories are not stored in this temporal lobe-hippocampal system. But then where are they stored? The cerebral cortex is the main possibility.

The most compelling evidence for long-term storage of factual information like vocabulary in the cerebral cortex comes from patients for whom damage to the neocortex resulted in selective loss of certain categories of words. Damage to left temporal-parietal regions or left frontal-parietal regions (Figure 5-3) might impair knowledge of one category of words—for example, small inanimate objects such as brooms and chairs—but not knowledge of words from another category such as living things. On the other hand, damage to the ventral and anterior temporal lobes can have the opposite effect. Elizabeth Warrington and asso-

FIGURE 5-3 The four major lobes of the human cerebral cortex.

ciates, who discovered these patterns of brain damage and word category loss, suggested that the particular sensory and motor systems used to learn about the world influence where information is stored in the brain. For example, people learn about living things primarily through vision, and many aspects of vision are coded in the temporal lobe, whereas people learn about inanimate objects like hammers and furniture by manual and postural movements, involving the parietal and frontal lobes.

In part because animals cannot speak, we have less knowledge about where information might be stored in their brains. When monkeys are taught visual discriminations, where they have to learn about particular objects and store that information

in long-term storage, damage to an intermediate region of the temporal lobe termed TEO can markedly impair these long-term visual memories. Remarkable studies by groups in Japan and at the National Institute of Mental Health in Bethesda, Maryland, report that when monkeys have learned to discriminate particular objects well, neurons in their temporal lobes seem to code these objects (and respond selectively to the sight of them). An unanswered question is whether this TEO region of the monkey cortex is where memories of objects are stored or whether TEO is just necessary to perceive the objects; in either case, damage to TEO impairs the animal’s ability to recognize objects. Studies such as these are only the beginnings of the study of a major scientific question; at present relatively little is known about how neurons and patterns of neural activity actually represent and maintain specific memory information.

Memory Consolidation and Retrograde Amnesia

The concept of memory consolidation is very old and very simple. It is essentially the idea that, when memories are first formed, they are relatively fragile and easily interfered with. Over a period of time they become much more firmly fixed and resistant to decay and interference. Consolidation has been proposed as an explanation of time-limited effects in retrograde amnesias—of why forgetting experiences that occurred just prior to brain damage is more likely than forgetting older memories. Allan Brown of Southern Methodist University has performed detailed analyses of studies of retrograde amnesia in humans and concluded that there is strong evidence for such temporally graded retrograde amnesia as well as evidence for a consolidation process in human long-term memory that occurs over periods of several years at least.

One problem with the evidence from human studies is that very little of it comes from controlled experimentation. You cannot concuss human subjects, starve them of oxygen, create lesions in the cerebral cortex, or induce massive convulsions (with

one exception, as we’ll see). But such treatments are possible with nonhuman subjects. One in particular has been studied in detail: the effects of an electric current applied to the head that is strong enough to produce massive disruption of the normal electrical activity of the cortex, unconsciousness, and a convulsion.

The classic study of electroconvulsive shock (ECS) was done by Carl Duncan at Northwestern University. Rats were given one trial a day for 18 days in a simple learning task in which they had to run from one side of a box with a grid floor to the other side when a tone came on to avoid getting a foot shock. Normal animals learned this task well and remembered to avoid the shock on the last 12 or so days of the test. Duncan ran this experiment on several groups of animals. One group was given ECS 20 seconds after the learning trial, another group 40 seconds after, and so on up to an hour or more. The results were dramatic. Animals given the ECS very soon after the learning trial learned nothing—they acted as if they had not learned any association at all between the tone and the shock. But there was a pronounced gradient such that animals given the ECS an hour after learning were not impaired at all compared to controls given no ECS.

So began a large and fascinating field of science. Many alternate ideas were proposed: Perhaps the ECS hurt, so animals were being punished; perhaps they were learning fear. One by one these hypotheses were overturned, and the consolidation view survived. Key experiments showed that if the animals were anesthetized and the seizure activity was limited to the brain using in-dwelling electrodes, the same memory impairment occurred. Massive interference with normal brain activity can markedly impair the consolidation of memories.

If treatments like ECS can interfere with memory formation, perhaps it would also be possible to facilitate memory formation. Many years ago Karl Lashley, a pioneering scientist who studied the brain mechanisms of memory, did just such an experiment. He gave rats a powerful stimulant drug and found that they learned a maze better than did nondrugged animals. (Unfortunately, they also ran faster, so it was not entirely clear whether

they actually learned faster or not. The drug affected their behavioral performance, but this was not necessarily due memory factors.) This issue was resolved years later in now-classic studies by James McGaugh and his associates at the University of California at Irvine. They introduced the post-trial treatment procedure. Animals were given a trial of training, perhaps in a maze. A stimulant drug was then administered right after the learning experience. The animal was tested the next day, after the effects of the drug had worn off. The results were striking: Stimulant-injected animals developed much better memories of the maze than did control animals injected with saline. The drug could not have affected performance during the learning experience because it was not injected until afterward. It must therefore have facilitated consolidation of the memories. Just as with ECS, there is a time gradient for memory facilitation. In rats, injections right after learning are most effective. Later injections are progressively less effective, and injections an hour or so after learning do not work in rats.

A number of chemicals and drugs can markedly enhance the formation of memories if injected after a learning experience. Most of this work has been done with animals, but similar results have been found with humans. Two of the most effective memory-enhancing drugs (in rats) are strychnine and amphetamine. Don’t try this at home. Strychnine is a deadly poison; it blocks inhibition in the brain and in higher doses leads to epileptic seizures and death. Amphetamine is a powerful and addictive stimulant and repeated use leads to psychosis.

Actually the body and brain produce their own memory consolidation agents, particularly in times of stress or anxiety—for example, the arousal hormone adrenaline. For both animals and humans, adrenaline can enhance memory consolidation and thus improve later retention of a learning experience. There are many substances that can enhance memory consolidation, the safest being glucose. If you eat a candy bar right after a learning experience, it can enhance your memory of the experience.

Is there such a thing as a memory pill? The substances we

discussed here, such as adrenaline and glucose, can enhance memories somewhat, depending on the circumstances. But there is no pill that can make ordinary memorizers into supermemorizers. The memory pill has become the goal of a major search by the pharmaceuticals industry, primarily because of Alzheimer’s disease, where the basic symptom is progressive loss of memory ability, due to brain tissue degeneration. There are now drugs on the market that can help memory a little in the early stages of the disease but as yet there are no really effective treatments.

To return to the idea of memory consolidation, the hippocampus and surrounding structures in the cortex are critically important for the formation of long-term memories. Patient HM and monkeys with damage to these structures cannot form long-term memories of their own experiences, even though their short-term working memory processes are normal. These cases are among the strongest evidence favoring the consolidation view and the hypothesis that the hippocampus and other structures are necessary to consolidate working memories into long-term memories. These cases also strongly support the distinction we have made throughout this book between short-term working memory and long-term memory.

There is another kind of evidence that supports the distinction between short-term and long-term memories. Studies with animals have shown that if drugs are injected that block gene expression and the manufacture of proteins, long-term memory formation is prevented, but short-term memory processes are not impaired. This strongly implies that long-term memory formation requires structural growth changes in neurons, changes that require proteins to be made.

Human Memory and Electroconvulsive Therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for the treatment of severe depression is a very common medical procedure in many countries. Its use is strongly endorsed by the National Institutes of Health: “Not a single controlled study has shown another form of treat-

ment to be superior to ECT in the short-term management of severe depression.” For many patients a series of two or more treatments a week for perhaps four weeks results in remission of the most severe symptoms of depression and reduction in the risk of suicide. It is not a cure, because recurrence of depression is quite common. The modern form of the treatment consists of inducing a convulsion by passing an electric current through the brain by means of electrodes applied to the head. The patient is first given a muscle relaxant, an injection of a fast-acting barbiturate that produces unconsciousness, and is then given the convulsion-inducing electrical current.

Here is a description of what it is like to undergo ECT, written by Norman Endler, a psychologist whose own depression was not responding to drug treatments:

I changed into my pajamas and a nurse took my vital signs (blood pressure, pulse, and temperature). The nurse and other attendants were friendly and reassuring. I began to feel at ease. The anesthetist arrived and informed me that she was going to give me an injection. I was asked to lie down on a cot and was wheeled into the ECT room proper. It was about eight o’clock. A needle was injected into my arm and I was told to count back from 100. I got about as far as 91. The next thing I knew I was in the recovery room and it was about 8:15. I was still slightly groggy and tired but not confused. My memory was certainly not impaired. I knew where I was. I rested for another few minutes and was then given some cookies and coffee. Shortly after eight thirty, I got dressed, went down the hall to fetch my wife, and she drove me home.

This description of ECT bears little resemblance to the descriptions often found in films, magazine articles, and in statements by certain advocacy groups (including the Church of Scientology). These sources depict ECT as a barbaric practice that robs people of their emotions and autobiographical memories. The idea that severe memory loss commonly results from ECT is widely believed, at least outside the medical specialties that actually use the procedure.

What is actually known about memory and ECT? First, massive erasure of personal memory is simply not a risk with modern

ECT. As Max Fink, psychiatrist and longtime proponent of ECT puts it, “There is no longer any validity to the fear that electroshock will erase memory or make the patient unable to recall her life’s important events or recognize family members or return to work.”

At the same time, there is evidence that some impairments of learning and remembering can result from ECT. For example, retrograde amnesia may occur following the treatment. This was evident in the results of an experiment by Larry Squire in which patients were tested for their memory of the names of television shows before and after ECT. The names were selected from shows that had originally aired for one season from one to 15 years earlier. Prior to ECT, patients’ memories for the names of the TV shows showed the usual forgetting curve, with memory accuracy generally decreasing the older the show. Following ECT, there was a selective impairment of memory for the more recently experienced shows only.

This result might be attributed to incomplete consolidation and increased vulnerability of the relatively recent experiences. However, there was another very important outcome of this experiment. On a later follow-up test, memory returned for the shows that could not be remembered immediately following ECT. This suggests that the memory failures in the first test were in fact only performance failure, reflecting the inaccessibility of otherwise intact memories. The ECT-induced memory loss and subsequent recovery in this experiment also resemble the pattern of loss and recovery often reported following a concussion.

Some of the most convincing evidence about ECT and memory loss comes from experimental studies in which depressed patients were randomly assigned to a real ECT treatment or a “sham” ECT treatment in which they underwent all the usual components of the ECT procedure (muscle relaxant, general anesthetic) but were not actually shocked and did not convulse. Experiments like these are very powerful from the standpoint of research design because they control for the effects that depression itself might have on memory, as well as the effects of drug-

induced unconsciousness on memory functions. Some experiments along these lines have also used double-blind controls, meaning that the patients did not know what treatment they would receive and the people evaluating a patient’s mood and memory functions after treatment did not know either.

What experiments like this have shown is that there appears to be no permanent loss of memories that existed prior to the ECT treatment, and no impairment of general cognitive functioning in the days following the procedure. In fact, memory functions sometimes seemed to improve following ECT. This is probably due to the effectiveness of ECT in alleviating many of the symptoms of major depression, which itself appears to interfere with memory functioning.

What are the risks to memory associated with ECT? They seem to be mild. ECT does seem to produce some retrograde amnesia, but this can be followed by memory recovery. It does seem to have some anterograde effects (for example, Professor Endler’s grogginess following the procedure), but these do not persist. There is still some concern that an extended program of ECT might have negative effects on cognition in general.

Why then does ECT continue to be controversial in many quarters? There are several reasons. One is that the safeguards and specific procedures used in modern ECT evolved from earlier procedures in which neither the benefits nor the risks were well understood, and in which the procedures used were crude by today’s standards. A second reason is that there is still no clear scientific understanding of why ECT works to alleviate symptoms of major depression, although there are many hypotheses involving hormonal changes, alteration of neurotransmitter activity, and possibly growth of new neurons in the hippocampus.

This may leave you wondering what the rationale for the ECT procedure was when it was first used 70 or more years ago. There are varying accounts. One is that it originated in the observation that patients suffering from both epilepsy and schizophrenia seemed to show a reduction in psychotic behavior following an epileptic seizure and that this rather naturally led to the specula-

tion that deliberately inducing a seizure might have the same result.

In any event, as scientific understanding of memory progresses, newer and more sensitive forms of memory testing will become available, and there will be continuing evaluation of ECT’s effects on memory and cognition. This is what Anne Donahue called for in a compelling personal account of her experience with depression and ECT. Although she thinks that ECT may have impaired her memory, she is thankful that she had a course of treatments: “I remain unflagging in my belief that the electroconvulsive therapy that I received may have saved not just my mental health but my life. If I had the same decision to make over again, I would choose ECT over a life condemned to psychic agony, and personal suicide.”

Virtual Lesions

In the last few years a new technology has been developed that might be an alternative to ECT and that might also be a valuable research tool for the study of normal human memory. It is called transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and it consists of generating a magnetic field in a coil held near the head (see Figure 5-4). The magnetic field penetrates the scalp and the skull and generates an electric field that can disrupt the normal electrical activity of neurons in the cerebral cortex. For example, when the coil is held near the motor cortex (a narrow band lying across the top of the cerebral cortex), it can cause the muscles of the thumb to twitch. Several studies of TMS as a treatment for depression, with sham treatment controls, have suggested that it temporarily reduces the symptoms and risks of major depression (but again for reasons that are not clear).

Unlike ECT, the TMS procedure is simple and apparently safe enough to use as a research tool to study brain function in normal subjects. In one study, subjects looked at pictures of familiar objects presented on a computer monitor, fixing their gaze on the midline of the display. A TMS coil was held over the visual pro-

FIGURE 5-4 Transcranial magnetic stimulation of the brain.

cessing areas in the right occipital-parietal lobes. After a few minutes of stimulation, subjects reported that the left half of the visual display could no longer be seen. When the coil was deactivated, their perception immediately returned to normal.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation has also been used in the study of memory. In one experiment it was applied over the left and right frontal lobes while subjects were either studying a set of pictures, or being tested for their memory of the pictures. The experiment was conducted as a test of Endel Tulving’s HERA theory (hemispheric encoding-retrieval asymmetry). This theory states that the left frontal lobes are more active during learning or encoding (trace formation), while the right hemisphere is more active during retrieval (trace access). The results of the experiment were consistent with the theory. Stimulation applied to the left-frontal lobes disrupted memory performance if applied during learning but not during testing, while stimulation applied to the right frontal lobes disrupted memory performance when applied during testing but not during learning. Interestingly, this seems to imply that if subjects were later retested without TMS, their “lost” memories would return. In any event, the TMS technology seems to provide something that until now has not been available

for studying human memory: a way of producing safe and reversible “virtual lesions.”

Dementia and Memory

Case histories like the one presented in Box 5-1 are all too common these days. There are several different conditions that consist of a steady, inexorable decline in the brain and its functions and lead to dementia. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common of these, and it is equally prevalent in men and women. The affected initially have trouble learning new material and eventually cannot learn at all. Death usually comes after 10 years or so and is often caused by other factors such as pneumonia. By this point the patient is unaware of his surroundings, does not recognize anyone, and is unable even to care for his own bodily functions. Some 10 to 15 percent of people over 65 develop the disease, as will one in every four Americans over 85.

The decline in memory with Alzheimer’s disease is dramatic, even in the early stages. Unlike normal aging, both short-term and long-term memory abilities are compromised and patients gradually lose their long-term semantic and personal memories. Eventually, everything goes. Simple tests show how marked the impairment can be even in moderately advanced cases. Patients have difficulty with such questions as:

-

How many wings does a bird have?

-

If two buttons cost 15 cents, what is the cost of a dozen buttons?

-

In what way are a tiger and a lion alike?

-

Draw the face of a clock set to 11:10.

This last question causes problems even in the early stages of the disease. Patients have difficulty placing the minute hand on the 2: instead they try to place it on the 10.

A number of tests have been devised to diagnose the initial stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Most are simple memory tests like

|

BOX 5-1 Harry seemed in perfect health at age 58, except that for a couple of days he had had the flu. He worked in the municipal water treatment plant of a small city, and there, while responding to a minor emergency, Harry became confused about the order in which the levers controlling the flow of fluids should be pulled. Several thousand gallons of raw sewage were discharged into a river. Harry had been an efficient and diligent worker, so after puzzled questioning, his supervisor overlooked the error. Several weeks later, Harry came home with a baking dish that his wife had asked him to pick up; he had forgotten he had brought home the identical dish two nights before. Later that month, on two successive nights, he went to pick up his daughter at her job in a restaurant, forgetting that she had changed shifts and was working days. And a week later he quite uncharacteristically became argumentative with a clerk at the phone company; he was trying to pay a bill that he had paid three days before. By this time his wife had become alarmed about the changes in Harry’s behavior. She insisted that he see a doctor. Harry himself realized that his memory had been failing for perhaps as long as a year, and he reluctantly agreed with his wife. The doctor did a physical examination and ordered several laboratory tests and an electroencephalogram (a brain wave test). The examination results were normal, and thinking the problem might be depression, the doctor prescribed an antidepressant drug. If anything, the medicine seemed to make Harry’s memory worse. It certainly did not make him feel better. Then the doctor thought that Harry must have hardening of the arteries of the brain, for which there was no effective treatment. Approximately eighteen months had passed since Harry had first allowed the sewage to escape, and he was clearly a changed man. He often seemed preoccupied, a vacant smile settled on his face, and what little he said seemed empty of meaning. He had given up his main interests, golf and working. Sometimes he became angry—sudden storms without apparent cause—which was |

those given above. But these tests only identify probable Alzheimer’s (or at least dementia) once the disease has progressed to the point where clear memory impairment and accompanying neuron loss in the brain have developed.

A test that shows promise in diagnosing the initial stages or

|

quite unlike him. He would shout angrily at his wife and occasionally throw or kick things, although his actions never seemed intended to hurt anyone. He became careless about personal hygiene, and more and more often he slept in his clothes. Gradually his wife took over, getting him up, toileted, and dressed each morning. Harry himself still insisted that nothing at all was wrong, but by now no one tried to explain things to him. He had long since stopped reading; he would sit vacantly in front of the television though unable to describe any program that he had watched. His condition slowly worsened. He was alone at home through the day because his wife’s school was in session. Sometimes he would wander out. He greeted everyone he met, old friends and strangers alike, with “Hi, it’s so nice.” That was the extent of his conversation, although he might repeat “nice, nice, nice….” He had promised not to drive, but one day he took out the family car. Fortunately, he promptly got lost and a police officer brought him home; his wife then took the keys to the automobile and kept them. When he left a coffee pot on the electric stove until it boiled dry and was destroyed, his wife, who by this time was desperate, took him to see another doctor. Harry could no longer be left at home alone, so his daughter began working nights and caring for him during the day until his wife came home after school. Usually he sat all day, but sometimes he wandered aimlessly. He seemed to have no memory at all for events of the day, and he remembered very little of the distant past, which a year or so before he had enjoyed describing. His speech consisted of repeating over and over the same word or phrase. Because Harry was a veteran, she took him to the nearest Veterans Administration hospital, 150 miles distant. Harry was set up in a chair each day, and the staff made sure he ate enough. Even so, he lost weight and became weaker. When his wife came to see him he would weep, but he didn’t talk, and he gave no other sign that he recognized her. After a year he even stopped weeping, and after that, she could no longer bear to visit. He lived on until just after his sixty-fifth birthday when he choked on some food, developed pneumonia as a consequence, and soon died. |

even predicting subsequent development of the disease has come from an unexpected source—classical conditioning—in studies by Diana Woodruff-Pak at Temple University and Paul Solomon at Williams College. An example of such a study of eye-blink conditioning is shown in Figure 5-5. Note the massive impairment in

FIGURE 5-5 Eye-blink conditioning in normal control subjects and Alzheimer’s patients. The graph shows the percentage of conditioned responses (CRs) in each group.

learning by early Alzheimer’s patients compared to normal age-matched controls. Note also that a few of the normal subjects performed as poorly as the Alzheimer’s patients. In a three-year follow-up study, several of these low-scoring normal people developed Alzheimer’s disease but none of the high-scoring normal people did!

Before examining the causes of Alzheimer’s disease we look briefly at another devastating form of dementia, Huntington’s disease, where genetic factors are clear. Huntington’s is a terrible disease with marked movement disorders, involuntary writhing movement of the limbs, together with rapidly developing brain degeneration, dementia, and death. It is due to an abnormality of a single dominant gene on chromosome 4. This means that 50 percent of all children of someone suffering from the disease will have the gene too and virtually 100 percent of these will also develop the disease. About half of those who have the gene will develop the disease before the age of 40 and the other half not until after 40. Someone with the gene may not be aware of this

fact and have children, half of whom will be destined to suffer the disease.

The defective gene can be identified in a simple test done on DNA from cells in blood or saliva. Unfortunately, there is no treatment. This raises serious issues about genetic counseling. One person is reported to have committed suicide after learning of his genetic diagnosis of Huntington’s disease by telephone without prior counseling.

As of this writing we do not know all the causes of Alzheimer’s disease. A clear brain pathology definitely identifies Alzheimer’s disease: senile plaques, BB-sized accumulations of debris left over from destroyed neurons surrounding a central core of protein called amyloid; tangles of neurofilaments inside neurons; and, ultimately, massive loss of neurons and brain volume. These are most prevalent in regions of the cerebral cortex critical for declarative and working memory: the medial temporal lobe–hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Actually, normal elderly individuals may also develop some plaques and tangles.

A possible lead to genetic factors in Alzheimer’s disease came with the discovery that people suffering from Down’s syndrome also had plaques and tangles and loss of neurons in the brain, but at a much earlier age, always before the age of 10 years. Children with Down’s syndrome are typically mentally retarded and have a collection of unusual symptoms, including folded eyelids. The genetic basis of Down’s syndrome is well known. These individuals have an extra chromosome 21. Down’s syndrome incidentally, is not inherited; it is caused by abnormality in the development of germs cells. Three copies of chromosome 21 means 50 percent more DNA and this means 50 percent excess protein product, possibly in the form of plaques and tangles.

The genetic factors in Alzheimer’s disease are rather complicated. There is a particular form of Alzheimer’s disease that involves at least three abnormal genes and is associated with early onset of the disease, before the age of 60. However those genetic factors account for only about 10 percent of Alzheimer’s patients. Another gene termed apoE on chromosome 19 is implicated in a

different way. There are actually three different forms of apoE—2, 3, and 4. It is only the apoE 4 that is associated with Alzheimer’s disease. But the presence of apoE 4 does not cause the disease; it simply increases the likelihood that the disease will develop in old age. The apoE 4 gene is present in some 40 percent of people who develop Alzheimer’s disease in old age. But this still leaves 50 percent of all Alzheimer’s patients with no known genetic causal factors.

The neurotransmitter acetycholine (ACh) may have some involvement in Alzheimer’s disease. Studies of the brains of a number of patients who died from Alzheimer’s disease have indicated a marked loss of neurons in the basal forebrain, which contains ACh neurons projecting to the cerebral cortex, and much lower levels of certain chemicals associated with the ACh system. But some loss of ACh neurons in the nucleus basalis also occurs in normal aging.

It has been known for some time that anticholinergic drugs, which counter the effects of ACh, impair memory. Drugs that block this enzyme lead to increased actions of ACh at these synapses. Such drugs facilitate memory in animals and humans. More ACh is good for memory. It is not yet known whether loss of ACh neurons is the sole or even a major cause of Alzheimer’s disease, or whether there is any causal relationship among the appearance of senile plaques, neuron loss in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, and the marked loss of ACh neurons in the nucleus basalis.

There is clear evidence in studies of normal young adults that drugs that enhance ACh function in the brain enhance memory performance and drugs that antagonize ACh impair memory performance. Unfortunately, these memory-enhancing drugs have unpleasant side effects. But new classes of drugs that antagonize AChE have been developed to treat Alzheimer’s disease.

Tacrine (Cognex) is one these drugs. It does have less severe side effects but may cause nausea and vomiting in some patients. Tacrine was evaluated in a series of clinical trials with Alzheimer’s patients. It seems to be most helpful in treating the

memory and cognitive impairments seen in the early stages of the disease. Patients on the drug show a modest but significant improvement on measures of basic cognitive skills. Tacrine does not prevent Alzheimer’s; it seems to slow development of the debilitating symptoms somewhat. But this still has important consequences. If patients on the drug can remain at home for just a few months longer before going to a nursing home, it will save billions of dollars, not to mention enhancing the quality of life for the patients, at least for this period of time. Another new drug, Aricept, appears to be somewhat more effective in slowing progression of the disease.

There has been much interest in the possibility of predisposing environmental factors in Alzheimer’s disease. An earlier hypothesis was the presence of aluminum. However, to date, no specific environmental villains have been identified.

So far we have considered ultimate causes about which little is proven beyond the genetic 10 percent. More is known about the immediate or proximal causes of Alzheimer’s disease. A protein present in cells, beta-APP (amyloid precursor protein), may be directly responsible for the abnormal accumulation of fibrillar material that kills neurons, resulting in tangles and plaques. But we still do not know why it happens.

The general notion is that certain genes may suddenly begin expressing proteins that lead to plaques and tangles or may cease producing proteins that prevent these abnormal phenomena, or both. If this proves to be the case, chemical therapies may be possible. Thus, if genes start expressing abnormal proteins, drugs might be developed that would prevent the expression of these proteins. Perhaps the ultimate preventive treatment will involve some form of genetic engineering. The causes of and possible treatments for Alzheimer’s disease are some of the most active areas of research today in neuroscience.