Memory: The Key to Consciousness (2005)

Chapter: 8 Language

8

Language

Language is the most astonishing behavior in the animal kingdom. It is the species-typical behavior that sets humans completely apart from all other animals. Language is a means of communication, but it is much more than that. Many animals can communicate. The dance of the honeybee communicates the location of flowers to other members of the hive. But human language permits communication about anything, even things like unicorns that have never existed. The key lies in the fact that the units of meaning, words, can be strung together in different ways, according to rules, to communicate different meanings.

Language is the most important learning we do. Nothing defines humanity so much as our ability to communicate abstract thoughts, whether about the universe, the mind, love, dreams, or ordering a pizza. It is an immensely complex process that we take for granted. Indeed, we are not aware of most aspects of our speech and understanding. Consider what happens when one person is speaking to another. The speaker has to translate thoughts into

spoken language. Brain imaging studies suggest that the time from thoughts to the beginning of speech is extremely fast, only 0.04 seconds! The listener must hear the sounds to figure out what the speaker means. He must use the sounds of speech to identify the words spoken, understand the pattern of organization of the words (sentences), and finally interpret the meaning. This takes somewhat longer, a minimum of about 0.5 seconds. But once started, it is of course a continuous process.

Spoken language is a continuous stream of sound. When you listen to a foreign language you do not know, the speakers seem to be speaking extremely fast, indeed producing a continuous stream of incomprehensible sounds. Yet in our own language we hear words. We actually learn to perceive sounds and words from the continuous stream of speech. A classic example is the r and l sounds. In the Japanese language these two sounds do not exist as separate sounds. Patricia Kuhl and her colleagues showed that while all young babies, including Japanese babies, easily distinguished between r and l sounds, Japanese adults are unable to tell the difference.

Early Learning of Speech and Language

Imagine that you are faced with the following challenge. You must discover the internal structure of a system that contains tens of thousands of units, all generated from a small set of materials. These units, in turn, can be assembled into an infinite number of combinations. Although only a subset of those combinations is correct, the subset itself is for all practical purposes infinite. Somehow you must converge on the structure of this system to use it to communicate. And you are a very young child.

This system is human language. The units are words, the materials are the small set of sounds from which they are constructed, and the combinations are the sentences into which they can be assembled. Given the complexity of this system, it seems improbable that mere children could discover its underlying structure and use it to communicate. Yet most do so with eagerness and ease, all within the first few years of life.

The rate of language learning by infants (from infantus, “without language”) and young children is quite amazing. Somewhere between 10 and 15 months of age the first word is spoken. But infants recognize and remember words well before then. Six-month-old infants shown side-by-side videos of their parents while listening to the words “mommy” and “daddy” looked significantly more at the video of the named parent. But when shown videos of unfamiliar men and women, they did not look differentially to “mommy” or “daddy.” By age 2 children know about 50 words, and by age 8 the average child has a vocabulary of about 18,000 words. So between the ages of 1 and 8, the child is learning an average rate of eight new words a day!

It appears that learning the meanings of new words by young children can be extremely rapid. Children ages 3 and 4 were given just one exposure of a new word. At a nursery school the children were told to “bring the teacher” the chromium tray, not the blue one (there were two trays, an olive one called “chromium” and a blue one). Upon later testing the children remembered that the word “chromium” represented a color, and some even remembered what color (olive). This extraordinarily rapid learning of new words by children has been termed “fast mapping” and has been demonstrated in children ages 2 to 11. How many words do you think a two-year-old is exposed to every day? The average is between 20,000 and 40,000! But, of course, most of this is repetition of common words the child already knows.

Babbling, a Universal Language

Babies the world over begin to babble between four and six months of age. Early on, babbling is the same in all languages and cultures. “Skilled” babbling sounds very much like language, but so far as we know it conveys no meaning. Infants of deaf parents babble normally. It appears that early babbling is largely innate, but by about 10 months of age babbling begins to become differentiated. English-speaking babies begin to babble differently from

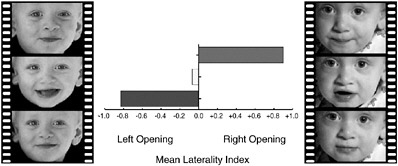

FIGURE 8-1 When smiling the left side of the baby’s opened more (left) and when babbling the right side of the mouth opened more.

French babies, who babble differently from Chinese babies, and so on.

It appears that the left hemisphere of the brain is more involved in the control of babbling. The left hemisphere is specialized for language function in most adults, whereas the right hemisphere is more concerned with emotions. The evidence for hemispheric control of babbling comes from very simple video recordings of babies’ faces made while they were babbling and smiling (see Figure 8-1). When babbling, the right side of the mouth is more opened and moving (left hemisphere), and the left side of the mouth is more involved with smiling (right hemisphere). These results would seem to argue that the neural determinants of babbling are fundamentally linguistic, that left hemisphere control for language function exists from birth.

In a striking recent study an optical method of measuring brain activation was used to compare activation of the left and right hemispheres of the brain when newborn infants (two–five days old) were listening to speech. This ingenious optical method is completely harmless—lights are shined on the scalp, and the light reflected back from the surface of the brain (cortex) can be measured. The newborns were played language spoken in “motherese” (see below) versus the same recordings played backward. The left brain hemisphere posterior speech areas (see below) showed much greater activation for forward than backward

speech. No such differences were seen in the right hemisphere. Indeed, in the first few months of life, speech elicits greater electrical activity in the left hemisphere and music in the right hemisphere, as is the case with adults. However, the right hemisphere is also much involved in language in young children.

Motherese, Another Universal “Language”

How do you speak to a young infant? You may not be fully aware that you are speaking motherese. The pitch of your voice rises, you drag out vowel sounds, you use very simple words, and you speak in a sing-song tone (“Heellooo, baaabeee”). Motherese is not limited to English. Groups of English, Swedish, and Russian mothers were studied when speaking to their infants and to adults. In all three languages motherese had exactly the same characteristics. Speaking to babies in this manner emphasizes the basic characteristics of vowels and syllables, providing the infant with a simplified example of the language. Adult speech is extremely variable, with many subtle variations from person to person. As someone said, “When it comes to understanding language it’s a phonetic jungle out there.” How is the infant to learn language correctly? Motherese helps provide a more uniform speech. But why do we speak motherese to infants? It is certainly not with deliberate intent to instruct them. It turns out that babies pay much more attention to motherese than to adult language. It would seem they are training us to speak motherese to them, an example of infants operantly conditioning adults!

Infants are able to discriminate speech sounds and words when as young as four days old and are sensitive to the rhythms of speech but not nonspeech sounds. Thus, newborns can discriminate sentences from Dutch and Japanese but not if the sentences are played backward. Very young infants are able to do this equally for all languages; they show a categorical perception of speech sounds. Adults do not have this ability. We are much better at discriminating critical speech sounds in our own language than in other languages. Infants begin to lose their ability to discriminate

speech sounds in all languages between the ages of 6 and 12 months, the very time when they are beginning to learn their own language.

Until recently it was thought that this ability of young infants to handle speech sounds in all languages was unique to humans. It now appears that this ability may be common to all primates. In a most intriguing study, it was found that cotton-top tamarin monkeys are able to distinguish between Japanese sentences presented normally or backward. It seems to be a basic ability of the primate auditory cortex.

What Is Language?

The basic elementary sounds of a language are called phonemes. They roughly correspond to the individual sounds of the letters. The total number of phonemes in all language is about 90. English uses 40, and other languages use between 15 and 40. Babbling infants can say most of them. This production of the basic sounds of language is called phonetics and it is clearly innate. All normal babies the world over do it in the same way.

The English language has rules for how these basic sounds can be combined into words. We have learned these rules but are not usually aware of them, only how to use them. In English the word “tlip” cannot exist—you can’t begin a word with a t followed by an l. You knew that but you were not aware of the rule. On the other hand, “glip” is fine; it just doesn’t happen to exist, as a word. As one linguist put it, if a new concept comes along and it needs a name, “glip” is ready, willing, and able.

Words are the next step, formed from combinations of phonemes, called morphemes. Morphemes are the elementary units of meaning. “Cars” is a combination of two morphemes, “car” and “s,” meaning more than one. Again, English has rules for combining morphemes, even though most of us cannot state them. You know that the plural of “glip” is “glips” and the past tense of “glip” is “glipped,” even though you have never encountered this word before. English has more than 100,000 morphemes combined

in various ways to yield the million plus words in the English vocabulary. A typical educated adult English speaker will have a vocabulary of about 75,000 words. Talk about memory storage!

But there is much more to language. The way words are arranged in sentences following rules is called syntax. Many rules have been spelled out, as in the grammar parsing some of us suffered through in school. But the rules existed long before any of them were described or written down. Finally, we come to the whole point of language, to convey meaning, termed semantics. Both the words and the ways they are combined into sentences convey meaning. “John called Mary” is not the same as “Mary called John.”

Interestingly, languages show little sign of evolution. All languages from English to obscure dialects of isolated aborigines have the same degree of complexity and similar general properties. They all have syntax—rules for making sentences—and although the particular rules differ for each language, in a general sense syntax is universal. This point may seem somewhat academic, but it is crucial, as in trying to determine whether apes can really learn language.

King James the first of England was a scholar and philosopher. Among other matters he was responsible for the King James version of the Bible. During his reign in the early part of the seventeenth century a hotly debated issue concerned the original human language. Some favored Greek; some favored other languages. But most scholars were convinced that there was an original language. King James devised an experiment to settle the matter. A number of newborn infants would be transported to an uninhabited island and cared for by Scottish nannies (he was Scotch) who were totally deaf and unable to speak. King James was convinced that the children would grow up speaking Hebrew. History doesn’t record whether the experiment was actually carried out. We know of course that there is no “original” language. But some authorities argue for a fundamental commonality in all languages, determined by the structure of the human brain.

Brain and Language

Since language is so important to our species, it is not surprising that substantial areas of the cerebral cortex, the “highest” region of the brain, are devoted to language functions. One of the great mysteries about the human brain is hemispheric specialization. For most humans, language functions are represented in the cerebral cortex of the left hemisphere, corresponding to the fact that most of us are right-handed (the left side of the cortex controls the right side of the body). Indeed, the original sign of hemispheric dominance was handedness. About 90 percent of us are right-handed in all societies and throughout history. Even our most remote ancestors that could be called humanlike, the australopithecines who lived in Africa several million years ago, may have been mostly right-handed. Australopithecines walked upright and apparently used crudely chipped stone stools, although their brain was only about the size of a modern chimp’s. Judging by how they bashed in the skulls of the animals they ate, they were right-handed.

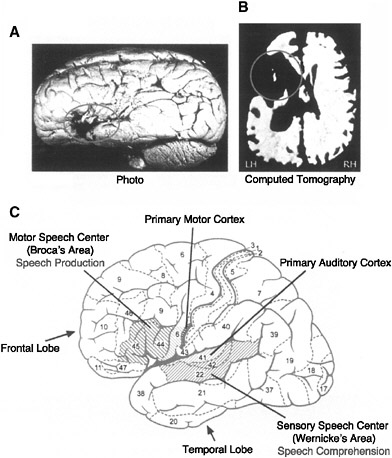

The first hint that language might be localized in the brain came about 140 years ago when the French neurologist and anthropologist Paul Broca reported the case of a patient who had lost the ability to produce language except for a single syllable “tan.” But he was able to understand simple questions and indicated yes or no by different inflections of “tan.” The patient died two years later, and Broca was able to obtain the brain. As it happened, he did not dissect the brain but preserved it whole. Luckily, the brain resurfaced 100 years later in an anatomical institute in Paris, and it is available for study today (see Figure 8-2). Actually the damage was extensive. It does not appear so while looking at the surface of the left hemisphere, but when a CT (computed tomography) scan was done, the damage was clearly much greater. Broca’s case was extreme. Patients with smaller lesions in the same general area of the frontal lobe of the left hemisphere have less severe symptoms. They are able to speak but have some difficulty doing so, have poor grammar, and omit many modifying words. This is the classic Broca’s aphasia.

FIGURE 8-2 (A and B) The brain of Paul Broca’s patient deceased in 1865. (C) Broca’s and Wernicke’s speech areas on the human cerebral cortex.

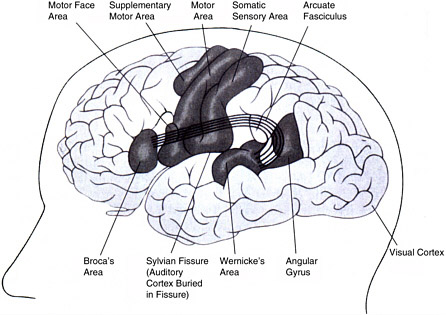

Several years after Broca’s patient was reported, the neurologist Carl Wernicke reported on a series of patients who produced speech that conveyed little meaning. Also, they could not understand speech. Their common area of damage was in the temporal lobe (Wernicke’s area; see Figures 8-2 and 8-3). Patients with damage to this region suffer from Wernicke’s aphasia. They speak fluently and grammatically but convey little meaning and cannot understand spoken or written language.

FIGURE 8-3 Language areas in the human brain.

Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas are interconnected by large bundle of nerve fibers (Figure 8-3). When this fiber bundle is damaged, as in a particular kind of stroke, a characteristic speech disability termed disconnection syndrome, occurs. You should be able to guess what this would be like. Wernicke’s area is spared, so language comprehension is fine. Broca’s area is spared, so speech production is also fine. But the patient’s speech is exactly like that of the patient with damage to Wernicke’s area—fluent but meaningless. It is no longer possible for Wernicke’s area to “transmit” meaningful speech to Broca’s speech production area. This must be very frustrating since the patient has good speech comprehension.

Figure 8-3 depicts the classical picture of the brain language areas. A frontal region (Broca’s) just anterior to the motor cortex is concerned with speech production, phonology, and syntax, and a posterior temporal-parietal area (Wernicke’s) is concerned with

semantics and meaning. But it is oversimplified. Thus, meaning is given by syntax as well as words. Consider the following two sentences:

The apple that the boy is eating is crunchy.

The girl that the boy is chasing is tall.

In the first sentence, syntax is not needed to understand the meaning; boys eat apples, but apples don’t eat boys, and apples can be crunchy, but boys are not. But in the second sentence, either the girl or the boy could be chasing the other and either could be tall. Syntax—that is, word order—tells us the meaning. Patients with damage to Broca’s area have no problem understanding the first sentence but have great difficulty with the second sentence.

The classical view of brain substrates of language was based on patients with brain damage and was developed well before the days of brain imaging and only for patients who came to autopsy. With the advent of brain imaging, it was possible to determine the extent of brain damage while the patient was still alive and, even more important, to identify brain areas that become active in various language tasks in normal people. The story is now more complex than the classic view, although the Broca’s and Wernicke’s area notion still has some validity.

Evidence now indicates that Broca’s area actually includes subareas concerned with all three of the fundamental aspects of speech: phonology, syntax, and semantics (meaning). This last aspect came as something of a surprise. Wernicke’s “area” also seems to involve subregions. One area is concerned with auditory perception of both speech and nonspeech sounds; another area is concerned with speech production, and a more posterior area responds to external speech and is activated by recall of words. It does appear that this last region is critical for the learning of long-term memories for new words. The total area of this posterior speech region is larger than the classical Wernicke’s area and includes parietal as well as temporal association areas of cortex.

Brain imaging studies indicate that the cerebellum, the ancient “motor” system, is also much involved in language. It is, of course, involved in the motor aspects of speaking but also in the meaning aspects of language, as in retrieving words from memory. A final complication from current brain imaging studies is that the right hemisphere is also involved in some aspects of language.

There does indeed appear to be some degree of localization for different categories of words in the posterior language area, judging by studies of patients with brain injury, thanks to work by Elizabeth Warrington in London and others. One patient, JBR, suffered extensive brain damage as a result of encephalitis. His aphasia was such that he was impaired for names of living things and foods but not for names of objects. Another patient, VER, following a major left-hemisphere stroke, had almost complete loss of comprehension of words for objects, even common kitchen items thoroughly familiar to her, but her memory for living things and foods was good. Patient KR, with cerebral damage, could not name animals but had no difficulty naming other living things and objects. Actually, she could not name animals regardless of the type of presentation (auditory or visual). When asked to describe verbally the physical attributes of animals (for example, what color is an elephant?) she was extremely impaired, but she could correctly distinguish colored animals from those that were not so colored when presented visually. Her symptoms suggest that there are two distinct brain representations of such properties in normal individuals, one visually based and one language based.

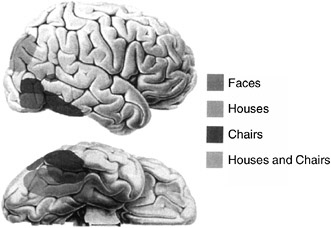

Brain imaging studies agree in showing a surprising degree of differential localization of different types of objects in the temporal area of the cerebral cortex. In addition to the face area, there appear to be differentially overlapping areas representing houses, chairs, bottles, and shoes (see Figure 8-4). It would seem obvious that there cannot be a separate area of cortex for each different object, there being billions of different objects in the world. Furthermore, it is difficult to see how a “shoe” area could have evolved since humans did not wear shoes until well after the brain had achieved its fully modern form. This represents yet another fascinating puzzle about the brain.

FIGURE 8-4 Faces, houses, and chairs activate different areas of the ventral temporal cortex.

Perhaps most extraordinary are studies of bilingual patients—for example, those who are fluent in Greek and English. Localized inactivation (a technique used in surgery) in central regions of Broca’s or Wernicke’s areas tended to disrupt language functions for both languages, but inactivation in the posterior language area outside classical Wernicke’s area could disrupt only Greek or only English, depending on the locus of inactivation. Yet another example is Japanese writing. There are two forms of written language—picture words (Kanji) and alphabetic writing (Kana). Brain damage can have differential effects on the ability to read and write these two forms of writing, depending on the area of damage.

All these data would seem to argue that our long-term memories for words and their meanings are stored in the posterior language area and that there is some degree of differential localization of word categories. But we have no idea yet of how words and other aspects of language are stored in terms of the actual circuits, the interconnections among neurons. There is much to be done.

An intriguing hint comes from work by one of the world’s

leading neuroanatomists, Arnold Scheibel of the University of California at Los Angeles. He and his associates measured the degree of dendritic organization for neurons in Wernicke’s area in a number of cadavers whose brains had become available and compared the anatomical data to the degree of education the people had had (see Figure 8-5). You may recall from Chapter 3 that dendrites (from the Greek for “tree”) are the fibers extending out from

FIGURE 8-5 The multitude of dendritic branches of a neuron.

the neuron cell body that receive input from other neurons via their axons. Dendrites are covered with little spines, each one a synapse receiving input from another neuron. The more dendrites a neuron has (its dendritic material), the more synapses it has from other neurons. The Wernicke’s area neurons from the brains of deceased people who had had a university education had more dendritic material than those from people with only a high school education, who in turn had more dendritic material than those with less than a high-school education. There is, of course, the usual chicken and egg issue here. Did the dendrites expand because of education or did the brains of those people with more dendrites seek more education? In some sense, increased connections among neurons may equate to increased knowledge.

The Critical Period in Language Learning

There is no question that children are more adept at learning language than are adults. Consider the following anecdote from Harvard neurobiologist John Dowling:

We brought our daughter to Japan at the age of five for a seven-month period and in just four months she became fluent in Japanese. Her pronunciation of Japanese words was generally superior to that of my wife, who had been studying the language for the previous three years!

It seems that there is a critical period in language learning but it is long, ranging from birth to adolescence. We are all aware of the fact that it is very difficult for adults to learn a second language to the point where they can pass for native speakers. There have been many studies of people’s initial efforts to learn a second language but not of their ultimate proficiency as a function of the age at which they began to learn it.

Elissa Newport of the University of Rochester answered this question in some ingenious studies. She selected people who had come to the United States from China or Korea at ages ranging from 3 to 39 and studied English as a second language for at least 10 years. They were all students or faculty members at the Uni-

versity of Illinois. Newport and her colleagues developed a test of English grammar competence. The results were striking. Those people who had come to this country before the ages of 3 to 7 performed as well as native English speakers. Thereafter there was a steady decline in performance, the worst being among people who began speaking English at ages 17 to 39.

Language is represented in both hemispheres of the brain in infants. Over the years leading up to adolescence, language representation shifts to the left frontal and temporal speech areas for most of us. Consistent with this, if the speech areas in the left hemisphere are damaged in childhood, there is good recovery. Unfortunately, with the same damage after the age of about 17, there is little recovery. In terms of synapse formation there is a steady increase in the number of synapses in the cortical speech areas in childhood that peaks around ages 3 to 5 and then declines to stabilize in adolescence. Similarly, brain energy utilization increases until about age 4, at which time the child’s cerebral cortex utilizes over twice as much energy as occurs in adults. This high-energy use persists until about age 10, after which there is a gradual decline to adult levels. So the critical period for language learning is very real; it is in the first several years of life and then gradually declines.

Reading

The human brain evolved to its fully modern form well over 100,000 years ago. No changes in brain structure or organization have occurred for a very long time. Yet written language, and hence reading, was invented only about 10,000 years ago. Reading, after all, is a very unnatural act. There was no evolutionary pressure to develop reading ability in the brain. Learning to read is a slow and difficult task for children, unlike learning to speak, and it is especially difficult for those who learn to read as adults. Our cultural evolution has forced us to use certain areas of our brain in tasks for which nature never intended them. Spoken language, on the other hand, evolved along with the evolution of our species and brain and is natural and adaptive.

An interesting question is: What areas of the brain are used or misused in learning to read? It appears that certain higher regions of the visual and association areas in the cerebral cortex may be enlisted, particularly a region called the angular gyrus (see below). There is tantalizing evidence that aboriginal peoples who have no written language have almost photographic visual memories. Such abilities would seem to be adaptive for survival. “Are the leaves bent a little differently than they were earlier along this place in the path?” Perhaps reading has co-opted these visual areas of the brain. There is a suggestion that children have better visual memories before they learn to read. Brain imaging studies indicate that wide regions overlapping both the posterior and anterior speech areas are engaged when we read.

The neurosurgeon George Ojemann has succeeded in recording the activity of single neurons in the human cerebral cortex during learning of word associations. The patients were undergoing neurosurgery to treat epilepsy. They were, of course, anesthetized during exposure of the brain and also given local anesthetics. They were then brought to awareness while the nerve cell recording was done (the brain itself has no sensation of pain). They had to learn associations between word pairs. A unique sample of neurons were found in the temporal lobe in the general region of Wernicke’s area (but in both hemispheres) that showed substantially increased activity only for associations that were learned very rapidly during initial encoding. These neurons could be distinguished from other neurons because they showed decreased activity during word reading (no learning involved) and increased activity during remembering of words just learned. These results are among the few examples showing single-neuron correlates of verbal learning.

Dyslexia

The aphasias are the major deficits in language caused by extensive brain damage. Dyslexia is a much more common language disorder and can range from mild to severe. Dyslexic children have trouble learning to read and write. An unfortunate case of a dys-

lexic child who was killed in an accident and came to autopsy has been described. There was a clear abnormality in the pattern of arrangement of the neurons in a part of Wernicke’s area. Although this is only one case, it raises the possibility that dyslexia may be due to brain abnormalities. Dyslexia is five times more common among boys than girls.

Dyslexia also tends to run in families. It is to some degree heritable, indicating that it has a genetic basis. Just recently, a gene was discovered that appears to be involved in dyslexia. Called DYXC1, it is located on chromosome 15. The chromosomal region containing DYXC1 had earlier been associated with dyslexia by studies of families with the speech impairment. There appear to be at least two different mutations of this gene that are involved in dyslexia. This gene, incidentally, is different from the recently discovered language gene (FOX p2) described later in this chapter. It seems likely that more than one gene will be found to be involved in dyslexia. After all, the condition ranges from very mild to severe.

A study by the National Institute on Aging examined the degree of activation of the angular gyrus relative to visual regions during reading in normal and dyslexic men (see Figure 8-3). This is a brain area above Wernicke’s area thought to be an auditory-visual association area critical for reading. In normal subjects there was a strong correlation between activation in the angular gyrus and visual regions. In marked contrast, in the dyslexic subjects there appeared to be a disconnection between the angular gyrus and the visual regions. There was no correlation between activities in the two regions. Additional studies of reading done at Yale University found decreased activation in the angular gyrus in dyslexics. Also found was decreased activation in Wernicke’s area and in the primary visual cortex in dyslexics relative to controls in a reading task.

In addition to problems with reading, many dyslexic or language-impaired children have trouble understanding spoken language. Ingenious studies by Michael Merzenich at the University of California at San Francisco, Paula Tallal of Rutgers Univer-

sity, and their colleagues showed that such children have major deficits in their recognition of some rapidly successive phonetic elements in speech. Similarly, they were impaired in detecting rapid changes in nonspeech sounds. The investigators trained a group of these children in computer “games” designed to cause improvement in auditory temporal processing skills. Following 8 to 16 hours of training over a 20-day period, the children markedly improved in their ability to recognize fast sequences of speech stimuli. In fact, their language functions markedly improved.

A group at Stanford University imaged the brain activity of a group of dyslexic children before and after the training treatment noted above. Before treatment there was a virtual lack of increased brain activity in the language areas when the children were reading. Remarkably, after training, activity in these areas increased to resemble that of normal children, in close association with improvement in reading skills in these children.

Stuttering

Stuttering is a language-speaking difficulty that plagues many people. It occurs much more frequently in males than females and clearly has a genetic basis—it runs in families. Analysis of the inheritance patterns indicates that it does not involve a single gene defect but rather several genes, as yet unidentified. Brain imaging studies show differences in the language areas (Broca’s and Wernicke’s) between stutterers and nonstutterers. However, as William Perkins of the University of Southern California, an authority on the subject, points out, this cannot be the cause of stuttering. Stuttering is an aberration of very high speed synchronization of producing speech sounds and is involuntary. The cortical speech areas, on the other hand, process information at a slower rate—syllables and thoughts occur at about the same rate, much slower than the rate of syllable production. Perkins thinks the cerebellum may be the critical structure for stuttering. It is specialized for very rapid timing, and its activities are “involuntary”; they do not rise to conscious awareness.

Evolution of Language

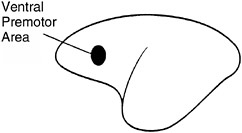

There are tantalizing hints from studies on monkeys of how human speech areas may have evolved. In the general region of the anterior cortex, where Broca’s area is located in humans, an entirely new premotor area appeared in monkeys, new in that it does not exist in other animals. It is just ahead of the primary motor area and is called the ventral premotor area (see Figure 8-6). In the monkey it serves as an additional cortical area for control of the muscles of the body. Neurons in this new motor area are activated when the animal performs visually guided reaching and grasping movements, as when the monkey reaches out and grabs something. In studying this area, the neuroscientist Giacomo Rizzolatti and his colleagues made an astonishing discovery. When the experimenter reached out and grabbed an object in front of the monkey, the neurons responded just as though the monkey had done the reaching. They termed these neurons mirror cells. This area seems to be involved in observational learning of visually guided tasks in monkeys.

Note that these ventral motor area neurons were able to establish a correspondence between seeing an act and performing it. As it happens, brain imaging studies in humans show that Broca’s area is also activated by hand movements. So perhaps in early prehumans Broca’s area-to-be was involved in matching observed vocal and hand gestures in communicating. As John Allman of the California Institute of Technology notes, these mirror neurons may be active when a human infant learns to mimic speech.

But this monkey area also receives visual input. Actually, in

FIGURE 8-6 The location of the ventral premotor area on the monkey cerebral cortex.

FIGURE 8-7 The McGurk effect.

normal human speech the appearance of the speaker’s face while speaking is important. Enter the “McGurk” effect, first described by a scientist named McGurk. The shape of the mouth while speaking helps determine the sound perceived. This is illustrated in dramatic movies of Baldi, a computer-generated face created by Dominic Massaro at the University of California at Santa Cruz. In the movies, Baldi is seen pronouncing various sounds while either the same or different sounds are heard. The illusion is compelling. If the image of the speaker’s face when pronouncing D is presented together with the acoustic sound B, the observer will hear an intermediate sound V, even though the actual sound is B (see Figure 8-7). The “McGurk” effect even seems to occur with infants only 18 to 20 weeks old. They look longer at a face pronouncing a vowel that matched the vowel sound they heard rather than a mismatched face.

As noted earlier, both young human infants and monkeys are able to distinguish the boundaries between similar speech sounds, such as ba and ga. In the temporal lobe of the monkey’s cerebral cortex, in the general region where Wernicke’s area exists in humans, there is a specialized auditory association area. Neurons in this area respond selectively to the vocalizations typical of the species. As it happens, these neurons are also very sensitive to the acoustic boundaries between speech sounds, as are monkeys and human infants.

Below this “speech” area on the temporal lobe is the monkey “face” area, where neurons respond selectively to monkey (and human) faces. Damage to this region in monkeys impairs their ability to respond appropriately to eye contact, a critically important social signal in monkeys and indeed humans. So it would appear that the beginnings of the human language areas were already developing in monkeys, in regions of the evolving brain that are critical for social interactions.

There is anatomical evidence that the region including Wernicke’s area is larger in the left hemisphere than in the right in most humans. Evidence of this enlarged left speech area can even be seen in our remote ancestors. The temporal lobe leaves a clear marking on the inner surface of the skull, which is different on the two sides because of the enlarged speech area on the left side in modern humans. The same enlarged left temporal area was found in the skull of our brutish-looking distant cousin, the Neanderthal. The Neanderthal skull that was studied is more than 30,000 years old and was found in France. Even more remarkable is the same enlarged speech area reported in one study of the left hemisphere of a skull of Peking man in Asia, our much more remote ancestor Homo erectus.

The astonishing quadrupling in size of the human brain over the past 3 million years must have been molded powerfully by natural selection. Language marks a major difference between humans and apes, and much of the human cerebral cortex is involved in language. It seems likely that improving communication with developing language gave a competitive edge in survival to big-brained social animals. Some great apes, chimps and orangutans, also have an enlarged area of the left hemisphere in a region analogous to the human language area, although it is nothing like the human asymmetry. Monkeys, however, do not have this type of cerebral asymmetry. Incidentally, the brains of our early modern ancestors (Cro-Magnon) were significantly larger than our brains, judging by skull sizes. It may have taken more “brain power” to survive in the primitive world. Thus, dogs have smaller

brains than wolves. But we stress that evolutionary arguments are always somewhat speculative.

A handful of African peoples speak by clicking their tongues. The two groups of Africans who speak this way are the !Kung (Bushmen) of Namibia and the Hadzabe of Tanzania. Genetic analysis suggests to some researchers that these clicking sounds may be vestiges of a language spoken by a common ancestor 112,000 years or so ago. Today, the click language is only spoken by the !Kung when hunting, perhaps in order not to scare their prey. In any event, even the click language has structure and syntax.

The Language Gene

Complex aspects of humans like intelligence and personality are influenced jointly by genes and experience. Such complex traits are generally thought to involve many genes. We noted earlier that autism, which is strongly heritable, is believed to involve somewhere between five and 20 different genes. Given the great complexity of language, it would seem likely that many genes are involved. Imagine the excitement in the field when a “language gene” was identified.

The discovery of this gene is a fascinating detective story in science. A few years ago a large family (called KEs) of several generations was discovered in which half the members suffered from a speech and language disorder. The fact that it was exactly half the members suggested that a single gene effect was involved. The affected members have problems articulating speech sounds, particularly as children, and in controlling movements of the mouth and tongue. But they also have great trouble identifying basic speech sounds and understanding sentences, and trouble with other language skills. They completely fail such tasks as “Every day I glip; yesterday I ___________.” The answer is, of course, “glipped,” as any four-year-old will tell you. They are particularly impaired in syntax. Sound familiar? In many ways this resembles the classic Broca’s aphasia.

More recently, a group of British scientists were able to show that the gene was on chromosome 7, over a region that contained 50 to 100 genes. Then an unrelated individual was found who had exactly the same language disorder. This person had what is called a chromosome translocation; chromosome 7 broke at a certain locus. It turned out that this locus was the region where the defective gene for the KEs family was thought to be. Making use of the results of the Human Genome Project, the investigators were able to localize and identify the actual gene, which they named FOXp2. In all of the affected members of the KEs family, but none of the unaffected members, this gene is defective. The gene is not defective in 364 chromosome 7 in unaffected people studied.

A brief word about genes. They are long strings made up of four different compounds called nucleotides. The four components are: adenine, thymine, guanine, and cytosine. Genes are “simply” long strings of these compounds, typically hundreds long, arranged in double strands—the famous double helix. These in turn determine the synthesis of proteins, which are long strings of amino acids. The coding is precise. A change in just one of the hundreds of nucleotides in a gene can markedly alter or impair the functioning of the gene. In the case of the language gene, a single guanine nucleotide at a particular locus is replaced by an adenine. This results in synthesis of an abnormal protein. (The normal protein is 715 amino acids long.) The normal FOXp2 gene is strongly expressed in fetal brain tissue and plays a critical role in the development of the cerebral cortex. Only one copy of the gene is defective in the KEs family, but this is apparently enough to impair normal brain development, at least for language functions.

But the story doesn’t end there. Two teams of scientists, in Germany and England, set about to sequence the FOXp2 gene in the chimpanzee, gorilla, orangutan, Rhesus monkey, and mouse. The last common ancestor of mouse and human lived some 70 million years ago. Since then there have been only three changes in the FOXp2 protein. Two of these changes occurred since the time that the human and chimp lines split, about 6 million years

ago. Strikingly, the third change, when all humans harbored the modern gene, occurred 120,000 years or so ago, the time when fully modern humans appeared on the scene.

A word of caution. This gene and its protein product seem particularly involved in the normal development, articulation, and other presumed functions of Broca’s area, including some aspects of language understanding. But there is much more to language. Other genes must also be involved.

Enter the Neanderthals

The Neanderthals had large heads, massive trunks, and relatively short but very powerful limbs. They evolved in Europe from an earlier hominid form about 350,000 years ago and emerged in their fully “modern” form about 130,000 years ago. Their bones are found throughout Europe and Western Asia. Then, between 50,000 and 30,000 years ago they disappeared from the face of the earth, at the time when modern humans swept through Asia and Europe from their origins in Africa.

The Neanderthals were a fascinating but now completely extinct side branch of humanity. They were more brutish looking than modern humans, with jutting brow ridges. But their brains were fully as large or larger than those of modern humans. Their skulls were differently shaped, with a lower frontal area, large bulges on the sides, and a larger area in the back.

There has been much speculation over the years about whether we killed them off or simply interbred with them. Actually, modern genetic analysis from tissue extracted from Neanderthal bones indicates that the last shared ancestor of Neanderthals and modern humans lived between 500,000 and 600,000 years ago. Furthermore, there appears to have been little Neanderthal contribution to the living human genome.

It would be inaccurate to describe the Neanderthals as simply primitive. They shared with our early ancestors the ability to flake stone tools, bury their dead, and to use fire, and they had a heavy dependence on meat. Skeletal remains of both types of humans

sometimes show severe disability, indicating they cared for the old and the sick. As one anthropologist put it, “There could be no more compelling indication of shared humanity.” It isn’t necessarily the case that we killed them off. Our early culture was much more complex and more adaptive to varying conditions. Our minds were better equipped to survive.

The discovery of the FOXp2 language gene suggests an answer to why we survived and Neanderthal did not. As was noted, this gene only appeared about 120,000 years ago in modern humans. Modern speech would seem to give our ancestors an enormous adaptive advantage in all aspects of survival. Although it is a bit of a guessing game as we improve our ability to analyze the genetics of tissues extracted from fossil bones, perhaps we can actually determine when the modern FOXp2 gene appeared and its impact on early human culture.

Learning and Language

The role of learning in language is a matter of some dispute. As noted, phonetics—speaking speech sounds—seems to be innate. All babies everywhere do it at the same stage. At the other extreme, the words of a given language are learned, as are the rules for putting words together. But perhaps the fact that all languages have this kind of structure, a syntax, could also be innate. Noam Chomsky, a pioneer in the modern analysis of language, argued that there is a “deep structure” to language that is universal and innate. Languages have to develop in a specific way in accordance with a genetic program controlling brain development. The discovery of the FOXp2 gene certainly lends credence to this view.

A common example of the innate view is the way children learn the rules for the tenses of verbs. At a certain age children use the regular past tense for irregular verbs: “I digged a hole.” No one ever taught them “digged,” only dug. But “digged” is the way it should be according to the rule for regular verbs. How can a child have learned this rule without having been instructed in it?

Cognitive and computer scientists have constructed artificial

neural networks in computers, actually complex computer programs that learn language. One such network was given the task of learning the past tenses of verbs. A very large number of correct past tenses were fed into the network. As the network learned, it began to generate “digged” for “dug,” regular past tenses of irregular verbs. It did this on a statistical basis. In the early stages of learning it experienced many more regular past tense verbs. Only with much additional experience did it master irregular past tenses.

So neural networks can learn the rules of language by experience, but what about children? In a most intriguing study at the University of Rochester, eight-month-old infants learned the segmentation of words from fluent speech solely on the basis of the statistical relationships between neighboring speech sounds. Furthermore, the infants accomplished this after only two minutes of training exposure. The investigators concluded that infants have access to a powerful neuronal mechanism for computation of the statistical properties of language. Shades of neural networks! The infant human brain is, of course, vastly more complicated than the most advanced computer neural networks.

Language in Animals?

There are some interesting examples that come close to language in monkeys. Most monkeys are social animals, living in groups, and they make sounds that clearly convey various meanings to the members of the group. Some neurons in the auditory cortex of a species of monkeys responded selectively to certain of their species-typical sounds but not to any pure tones. They responded like feature-detector neurons to sounds that conveyed meaning, as noted above.

An extraordinary example of a tiny “language” in monkeys was described by Peter Marler and his associates, then at Rockefeller University. They were studying vervet monkeys living freely in their natural state in Amboseli National Park in Kenya. Vervet monkeys make alarm calls to warn the group of an

approaching predator. All the adult animals make the same three different sounds to identify three common enemies: leopards, eagles, and pythons. The leopard alarm is a short tonal call, the eagle alarm is low-pitched staccato grunts, and the python alarm is high-pitched “chutters.” Other calls also could be distinguished, including one given to baboons and one to unfamiliar humans but not to humans they recognized.

The Rockefeller group focused on the leopard, eagle, and snake alarms. When the monkeys were on the ground and one monkey made the leopard alarm sound, all would at once rush up into the trees, where they appeared to be safest from the ambush style of attack typical of leopards. If one monkey made the eagle alarm, they would all immediately look up to the sky and run into the dense bush. When a python alarm was made, they would all look down at the ground around them. The investigators recorded these sounds and played them back to individual monkeys, with the same results. Perhaps most interesting were the alarm calls of the infant monkeys. The adults were very specific. The three alarm sounds were not made to the 100 or so other species of mammals, birds, and reptiles seen regularly by the monkeys. The infants, on the other hand, gave the alarm calls to a much wider range of species and objects—for example, to things that posed no danger, such as warthogs, pigeons, and falling leaves. When an infant would make such an error, a nearby adult would punish the infant. Even the infants, however, understood the categories; they gave leopard alarms to terrestrial mammals, eagle alarms to birds, and python alarms to snakes or long, thin objects. As the infants grew up, they learned to be increasingly more selective in the use of alarm calls. Why a given monkey would sound an alarm call is an interesting question. By doing so this monkey places himself in greater danger because the predator can notice him. Why then this altruistic behavior in monkeys?

The alarm calls are perhaps similar to phonetic expressions in humans; they are innate. But the objects of the calls—leopards, eagles, and so on—must be learned, just as humans must learn the meanings of words. Of course, this tiny “language,” consisting of one-word sentences, has no syntax.

“Hurry!” “Gimme toothbrush!” “Please tickle more!” “You me go there in!” “Please hurry!” “Sweet drink!” No one would be surprised to learn that the speaker of these utterances was a small child. The intended meaning is clear, but the grammatical structure is primitive. But it may surprise you to learn that the “speaker” was a chimpanzee. Beatrice and Robert Gardner obtained Washoe, a one-year-old female chimpanzee, from the wilds of Africa and raised her in a trailer “apartment.” During her waking hours, Washoe was constantly with human companions. She did not learn to speak English; in fact, Washoe did not learn to “speak” at all. The chimpanzee was taught American Sign Language. Many other experimenters had attempted verbal language training of chimpanzees and had failed. The Gardners reasoned that such failure was not due to an innate intellectual inability to learn language. Instead, it was due to the limitations of the animal’s vocal apparatus. There is good reason to use the chimp as an animal model of language learning. The chimp is the closest living relative of the human species; 97 percent of the DNA in chimps and humans is identical.

From the very beginning, the Gardners “talked” to Washoe only in sign language. They started with a very limited vocabulary of the most important or meaningful objects in Washoe’s environment, such as concepts of self and food, and gradually built the vocabulary. Washoe was rewarded first for trying to manipulate her fingers in imitation of the Gardners and then for making signs that were successively more like the desired ones. Finally, Washoe was rewarded only for making the desired signs. She learned rapidly. After several months of training, she had mastered 10 syllables. In three years her vocabulary increased to more than 100 words. Even more important, Washoe showed an amazing ability to generalize the signs to many situations other than the teaching situations. Gradually, she began to combine the signs into rudimentary phrases and sentences, using the signs spontaneously and appropriately. For example, when she wanted to go outside and play, she would make the appropriate sign with her hands. Another sign, pantomiming “peek-a-boo,” indicated that

she wanted to play a particular game. In the end, she was forming sentences of up to five words.

Was Washoe exhibiting “real” language? She certainly was communicating her wants, needs, desires, emotions, and reactions. She was able to carry on two-way communication with her experimenters. However, her language behavior was not at all like that of a child. Washoe was just as likely to say “Hurry! Gimme! Toothbrush!” as she was to say, “Gimme! Hurry! Toothbrush!” She did not seem to exhibit grammar and syntax.

So the key issue with Washoe (and Kanzi; see Box 8-1) is whether she will exhibit syntax. To date, the jury is out. On the other hand, Washoe, Kanzi, and other chimps have learned to communicate with humans very well. Indeed, such “talking” chimps provide a fascinating window on the mind of another species. Chimps, incidentally, may have some degree of self-awareness, judging by their behavior in front of a mirror.

|

BOX 8-1 A discovery that may prove to be extremely important has been made by Sue Savage-Rumbaugh and Duane Rumbaugh, working at the Yerkes Primate Center in Atlanta, Georgia. Researchers there used a simple language (called Yerkish) made up of symbols to communicate with chimpanzees; the chimps can communicate by pressing the symbols on a large keyboard. As in other studies, the chimps learned to do this very well; they could communicate their wants and feelings, and they pushed the correct symbols showing pictures of objects. As in other chimp studies, the Rumbaugh chimps did not learn to respond to spoken language. The Rumbaugh’s previous work had all been done with the common chimp (Pan troglodytes). The pygmy chimp (Pan paniscus) is a different species found only in one region of Africa. The pygmies are not actually much smaller than the common chimp but have longer and more slender bones, tend to walk upright on their feet more of the time, and have a much wider range of natural vocalizations. They seem more humanlike. Indeed, they differ so much from common chimps that a separate genus has been proposed: Bonobo. Matata was one of the first pygmy chimps the Rumbaughs studied. She was caught wild and her son, Kanzi, was born at Yerkes. In contrast to common chimps, at six months of age Kanzi engaged in much vocal babbling and seemed to be trying to imitate human speech. From this time until age 2 1/2 Kanzi accompanied Matata to her Yerkish training sessions. He was then separated from his mother for several months while she was being bred and was cared for by humans. The Rumbaughs decided to try to teach Kanzi Yerkish in a manner more like that of natural language learning in humans (no food reward for a correct response, no discrete trial training). He began using the keyboard correctly and spontaneously, which no common chimp had ever done. And quite by accident, it was discovered that Kanzi was learning English! Two of the experimenters were talking together. One of them spoke a word to the other and Kanzi ran to the machine and pressed the correct symbol for that word. Upon testing, Kanzi proved to have a vocabulary of about 35 English words at that time. More recently, it was reported that Kanzi has begun speaking “words.” The chimp started making four distinct sounds corresponding to “banana,” “grapes,” “juice,” and “yes.” Mind you, the sounds Kanzi made were not at all like the sounds of English words. But according to the experimenters, he used the four distinctive sounds reliably to refer to the appropriate objects. As far as we know, this is the first report of a chimp “speaking” discrete sounds to refer to objects. |