Memory: The Key to Consciousness (2005)

Chapter: 7 Emotional Learning and Memory

7

Emotional Learning and Memory

Emotions are among the most powerful forces in human behavior. This is particularly true for learning and memory. The carrot and the stick, rewards and punishments, are the most effective ways of training animals and humans. Food rewards and unpleasant stimuli like loud sounds and electric shocks are extremely effective in training animals to learn anything they are capable of performing. Except in the laboratory, such direct rewards and punishments are not common for people. Instead, social approval and disapproval and more remote rewards like money are key to much human learning and behavior. Considerably more is known about the role of negative emotions and their brain systems in learning and memory than is true for positive emotions.

Fear

Fear and anxiety are compelling emotions (see Figure 7-1). Intense anxiety when remembering or reliving traumatic events can exert

FIGURE 7-1 The Scream.

disruptive effects on people for many years. Indeed, the problem is not so much being able to remember such traumas but instead being able to forget them.

One of the most famous (or infamous) experiments in psychology involved frightening a baby. John Watson, a pioneering psychologist, was convinced that most human behavior, including fear, is learned. He set out to demonstrate this in his experiment with “little Albert,” together with his wife-to-be, Rosalie Rayner, in 1920. Little Albert was about 10 months old at the time. Luckily films were made of the experiment.

First, Albert was presented with a tame white rat. He petted the rat and showed no fear (see Figure 7-2). When the rat was given again to Albert, Watson stood behind him and made a very loud clanging sound by hitting a steel bar with a hammer. The loud noise greatly disturbed Albert and made him cry. Albert received seven such pairings of white rat and noise, an example of Pavlovian conditioning. Five days later Albert was presented with a variety of objects, including wooden blocks, Watson’s actual

FIGURE 7-2 Little Albert being terrified by John Watson.

head, and a white rabbit. Albert showed intense fear of the white rabbit, a somewhat negative reaction to Watson’s head, and no negative reaction to the blocks. Watson argued from this experiment that fear is learned, which was certainly true here, and that little Albert had developed a phobia to white furry objects. One wonders if little Albert went through life incapacitated by a fear of white furry creatures. Unfortunately, there was no follow-up study of Albert as an adult.

It seems that most human fears are learned, from the minor (or not so minor) fear of speaking in front of a group to incapacitating fears of horrifying events that can lead to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). But are all fears learned? It seems clear that lower animals have genetically programmed innate fear re-

sponses to certain types of stimuli. A classic example is the effect of hawks on chickens. When chickens see a silhouette of a hawk flying overhead they run and hide and show every evidence of fear. But if that same silhouette is flown backward (in which case it resembles a goose) over the chickens, the chickens are not disturbed.

A very simple example of an innate behavior is bug catching by frogs. Frogs are programmed to strike out with their tongues at small buglike objects flying past, but only if they are moving. A frog will starve to death in a field of perfectly edible dead bugs. The decision to strike at bugs is made in the eye itself. The relatively simple neural networks at the back of the eye (retina) activate the brain tongue-strike reflex only when stimulated by moving bug like objects. There are neurons in the frog retina that serve as bug detectors, but they are activated only by small irregularly moving objects. It is not difficult to see how evolution could shape these simple neural circuits in the retina of the frog; they are genetically determined. Frogs that were not good bug catchers didn’t survive long enough to reproduce. Judging by the size and shape of their eye sockets and brains, the same appears to be true for dinosaurs. These animals had no need to think about the appearance of the bug or other prey, no need to analyze the stimulus in the brain. The eye does it all. In these primitive animals seeing is indeed in the eye of the beholder.

Evolution took a very different tack in mammals and humans. The human eye codes only the simplest aspects of stimuli, basically the tiny light and dark spots, the pixels, that make up visual scenes. This simple information is projected to the brain, where it is synthesized into perceptions of objects. Decisions about the nature of stimuli, be they bugs or bears, are made in the brain. This was a profoundly important development. We can learn to perceive and recognize any visual stimulus because analysis of the visual world is done in the brain rather than the eye. We can learn to perceive letters and words, to read, which could never have happened if our perceptions were formed in the eye, as they are in the frog.

Are Fears Innate or Learned?

The famous psychoanalyst Karl Jung argued that humans do have genetically predetermined responses to certain types of stimuli and situations, what he termed archetypes. Snakes are a case in point. Most people are afraid of snakes, even though few of us have ever been injured by one. In the primate laboratory the standard fear-inducing stimulus is a realistic toy snake. For many years it was thought that monkeys’ fear of snakes was innate, determined genetically. It turns out that most laboratory monkey colonies were started with monkeys caught in the wild. In the jungle, large snakes prey on monkeys and wild monkeys are terrified of them, presumably because of experience. Infant monkeys born in the laboratory apparently do not show fear of snakes upon first exposure in the absence of their mother. But if the infant is with his mother and the mother shows signs of fear, so will the infant and will do so in the future. It would appear that the fear of snakes by monkeys may at least in part be learned and passed from generation to generation.

When the daughter of one of the authors (RFT) was very young and just beginning to talk, one of her words was “bow-wow” for our dog. We were out on the lawn one day and a garter snake wiggled past. Kathryn smiled and pointed at the snake and said, “bow-wow.” She was clearly not afraid (her mother was terrified of snakes and Kathryn quickly learned to become scared too). Interestingly, even though she didn’t yet know the word for snake, Kathryn had the right idea; it was a living thing like the dog. This sort of reasonable overgeneralization is very common in toddlers who are just learning to talk.

But the fact remains that most people are afraid of spiders and snakes. Do humans have some sort of genetic predisposition to learn to be afraid of such creatures that in earlier times threatened the survival of our ancestors? If there is a genetic basis for these fears, then genetic variation must exist—some people must be more afraid of spiders and snakes than others, which does seem to be the case. Of course, this argument overlooks the possibility that people have different experiences with spiders and snakes.

Actually, phobias of objects and situations that would have posed serious threats to our early ancestors—snakes, spiders, heights, enclosed spaces, seeing blood, darkness, fire, and strangers—are much more common than phobias about equally dangerous items that our ancient ancestors did not have to deal with, such as stoves, bicycles, knives, and cars.

This notion that humans have predispositions to learn to fear certain types of stimuli has been tested in the laboratory. Volunteers were given fear training by pairing various visual stimuli with unpleasant (but not harmful) electric shocks. The stimuli included snakes, spiders, houses, and flowers. When pictures of these objects were paired with electric shocks, people developed conditioned (that is, learned) fear of the pictures, much as little Albert did with the white furry objects. Here the learned fear responses, such as increased heart rate and sweating of the palms, were emotional in nature. The volunteers (who by this time may have had second thoughts) were then given repeated exposures to the pictures without shock to see how quickly they would forget or extinguish the fear responses. The results were striking—people quickly stopped showing fear of objects like houses and flowers but did not stop showing fear of snakes and spiders. Once learned, these fears could not easily be forgotten.

It seems we do have some sort of predisposition to learn to fear certain types of creatures and to remember these fears. In a sense this would seem to support Jung’s notion of genetically programmed “archetypes” in humans. As we saw in our discussion of memory development, newborn humans come into the world with many genetically determined predispositions—for example, to prefer faces to other types of stimuli. We have some beginning idea of how the brain codes faces but as yet no understanding of the brain bases of more complex predispositions or archetypes.

Flashbulb Memories

Older Americans will remember where they were when they learned that President Kennedy had been assassinated. For most of us it was an intensely emotional experience. Ten years after the

assassination, Esquire magazine asked a number of famous people where they were when they heard the news. Julia Child, a well-known culinary expert of the time, was in her kitchen eating soupe de poisson, the actor Tony Randall was in his bathtub, and so on. As Esquire said, “Nobody forgets.”

It is not just the fact that Kennedy was killed that is remembered. As Roger Brown, a distinguished psychologist at Harvard who coined the term “flashbulb memory” stressed, we don’t need to remember this fact; it is recorded many places. What is remarkable about flashbulb memories is that we remember our own circumstances, where we were and what we were doing upon hearing the news. We remember the trivial everyday aspects of life at that moment in time; they are frozen in memory.

But how accurate are such flashbulb memories? A classic study by Ulrich Neisser involved the Challenger disaster. In January 1986 the Challenger space shuttle blew up just after liftoff. The event was particularly horrible because a schoolteacher was on board and her pupils were watching the lift-off on television. Neisser queried a group of college students the day after the disaster and again two and a half years later. Consider the following two quotes:

When I first heard about the explosion I was sitting in my freshman dorm room with my roommate and we were watching TV. It came on a news flash and we were both totally shocked. I was really upset and I went upstairs to talk to a friend of mine and then I called my parents.

I was in my religion class and some people walked in and started talking about [it]. I didn’t know any details except that it had exploded and the schoolteacher’s students had all been watching which I thought was so sad. Then after class I went to my room and watched the TV program talking about it and I got all the details from that.

The first report is from a college senior two and a half years after the event. The second report is from the same young woman taken the day after the event. Interestingly, at the interview two and a half years after the event, she was absolutely certain her memory was completely accurate, even though it was not.

Several other studies of flashbulb memories have similar findings. There seems to be little relationship between how accurate the memory is and how certain the person is that the memory is in fact accurate. But it does seem to be the case that the more closely a person is involved in a traumatic event, the better it is remembered. Neisser studied people who had been involved in the 1989 earthquake near San Francisco soon after the event and a control group from Atlanta who had heard about the earthquake on television. Several years later, those who had actually experienced the earthquake had much more accurate memories than did those of the Atlanta group.

Suppose we were to ask these two groups what they were doing 35 days after the earthquake. Assuming no special events had occurred on that day, the memories of the people in both groups would be virtually nonexistent. So flashbulb memories are especially well remembered, but distortions can alter these memories over time. The memories become less accurate, but the certainty of their accuracy does not.

A recent study measured college students’ memories of the 9/11 tragedy at various times after the event. All students were initially tested the day after 9/11. Then one group was tested at a week, another group at six weeks, and a third group at 32 weeks after 9/11. As a control for nonemotional memories, each student was asked the day after 9/11 to pick an ordinary day between 9/7 and 9/11 and describe the events of that day. Each student picked a day when something ordinary like attending a party or a sporting event or even studying had occurred. In addition to measuring the accuracy of the memories, students were asked to indicate the vividness and emotionally arousing aspects of the memories. The results were surprising. Both 9/11 and everyday memories were remembered well and, most important, equally well over the 32-week period; however, the 9/11 memories were reported to be much more vivid and emotional. In this study, at least, flashbulb memories were remembered no better than ordinary memories but were thought to be much more vivid and accurate. But there is a problem with this study. The students rehearsed their memo-

ries for both days soon after. If the ordinary day had not been so highlighted in their memories, it might not have been remembered as well as the events of 9/11.

Emotionally charged memories can elicit extreme emotional responses even if the memories are completely false. In a Harvard study, people who claimed to have been abducted by space aliens observed videotapes of their earlier recorded stories of these events. As they watched the videos they showed markedly increased heart rate, sweating, and muscle tension—all signs of extreme emotion, particularly fear and anxiety. Recall our discussion of false memories in Chapter 5.

We think now that flashbulb memories are a milder aspect of learned fear and anxiety, a continuum of emotionally charged memories that range from minor to catastrophic. Even very mild emotional shading can influence memory. People were told a story with visual slides in two different ways. One version seen by one group of people was rather dull, indeed boring, but the version seen by another group of people was emotionally arousing. In both versions a mother and her son visit the father at his workplace and see him perform a task. In the neutral version the father is a garage mechanic working on a damaged car. In the emotional version the father is a surgeon operating on a severely injured accident victim. In one slide the surgeon is shown bending over the patient. Two weeks later the two groups were given a surprise memory test (they were college students). People who had seen the emotional version of the story remembered the basic plot of the story better than those who had seen the boring version.

Fear and the Amygdala

In recent years a great deal has been learned about how the brain operates to generate our experiences of fear and emotional memories. The key actor is a structure called the amygdala (Latin for “almond,” for it is shaped like one) buried in the depths of the forebrain. Basic studies with animals years ago showed the critical role of the amygdala in fear. Rats are terrified of cats, seem-

ingly an innate fear. Place a cat on top of a laboratory rat’s cage and the rat will cower in the corner of the cage in abject fear, a behavior termed freezing. By remaining immobile the rat stands a chance of not being seen by the cat, an adaptive behavior shaped by evolution. Suppose we now destroy the amygdala on each side of the rat’s brain. This operation does not appear to have much effect on the rat’s normal activities. But present the rat with a cat and the now-foolish rat will climb all over the cat. Its innate fear of cats has been abolished. It has also been documented that direct electrical stimulation of the amygdala in humans elicits intense feelings of fear and anxiety.

The amygdala is also critical for learned fears. Place a normal rat in a cage with a grid floor, sound a tone, and then briefly electrify the grid with a current that will feel painful to the rat (but not strong enough to cause any damage to the rat’s paws). After even one such experience the rat learns to associate both the cage and the tone with the unpleasant shock; it learns to be afraid. The next time the rat is placed in the cage or hears the tone, it will freeze in fear. But if the amygdala has been destroyed, the rat does not learn to be afraid in this situation.

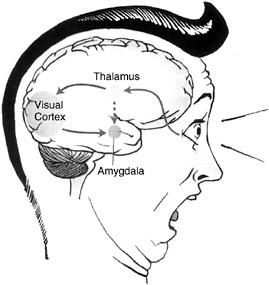

The amygdala is ideally placed in the brain to serve as the arbiter of fear. It receives information from visual and auditory regions of the brain and information about pain (see Figure 7-3). In turn it acts on lower brain regions concerned with both the emotional and behavioral aspects of fear (see Table 7-1). It can control heart rate and sweating of the palms (in humans) and behaviors like freezing, flight, or fight, about the only behaviors available to deal with immediate threats.

Monkeys with damage to the amygdala also show lack of fear and like rats (and humans) cannot be trained to show fear of situations associated with shock. Perhaps more importantly, they develop severe social problems. Monkeys, like humans, live in social groups, but in monkeys the social hierarchies are much more extreme. One alpha male rules the group, and there is a strict pecking order all the way down to the lowliest monkey, who is picked on by everyone. If the alpha male’s amygdala is destroyed, the

FIGURE 7-3 Visual input to the amygdala.

monkey quickly descends the social scale. Indeed, any monkey in the group whose amygdala has been damaged loses the ability to cope with social interactions and becomes an outcast or may even be killed. The amygdala thus plays an important role in social behavior. How this can occur became clear in recent years when humans with amygdala damage were studied.

There is an extremely rare hereditary disorder called Urbach-

TABLE 7-1 Biological Signs of Fear and Anxiety

|

Measures of Fear in Animal Models |

Human Anxiety |

|

Increased heart rate |

Heart pounding |

|

Decreased salivation |

Dry mouth |

|

Stomach ulcers |

Upset stomach |

|

Respiration change |

Increased respiration |

|

Scanning and vigilance |

Scanning and vigilance |

|

Increased startle |

Jumpiness, easy startle |

|

Urination |

Frequent urination |

|

Defecation |

Diarrhea |

|

Grooming |

Fidgeting |

|

Freezing |

Apprehensive expectation—something bad is going to happen |

Weithe disease in which, beginning in childhood, the amygdala progressively disintegrates. The brain tissue in the amygdala becomes calcified on each side of the brain, with apparently little damage to other brain structures. One such patient was studied in detail by neurologists Hanna and Antonio Damasio.

At the time of testing Miss A was about 30 years old, and her intelligence tested within the normal range. She was trained in a fear-learning procedure, in which neutral stimuli like colored slides and weak tones were paired with a very loud sound from a boat horn, a procedure much like the one Watson used on little Albert. Learned fear was determined by measuring the increase in skin conductance in the palm of the hand. The skin on the palm conducts electricity much better when the sweat glands are active. This is measured by applying a weak current to the palm, so weak that the person cannot feel it. Increased palm sweating (skin conductance) is a good measure of emotional arousal and fear.

Miss A and the control subjects were given a number of training trials pairing the neutral colored slides and weak tones with the boat horn. Both the control subjects and Miss A showed the same large increase in skin conductance (palm sweating) in response to the boat horn alone, as would the reader, for it is very startling. After training, the control subjects learned to give the same increase in skin conductance to the neutral stimulus, an example of Pavlovian conditioning. But Miss A showed no increased response at all to the neutral stimuli—no sign of learned fear. Unlike little Albert and normal adults, she could not be conditioned to show or experience fear.

Unlike monkeys with amygdala lesions, Miss A is more or less able to cope with life. She does have a history of inadequate social decision making and failure to maintain employment or marital relationships and depends on welfare, but she is not a social outcast and is a rather talented artist. Perhaps the most surprising aspect of Miss A is her complete inability to identify facial expressions of fear in others. Not only can she not learn to be afraid, she cannot perceive fear in others.

Miss A and normal control people were tested on their ability

to identify pictures of faces displaying basic emotions: happiness, surprise, fear, anger, disgust, and sadness. The emotions displayed in the pictures of faces were all easily and correctly identified by the normal subjects. Astonishingly, Miss A correctly identified all the emotional expressions except fear. But she had no trouble identifying the fearful faces as faces; she just couldn’t tell if they were showing fear. Indeed, she is able to draw pictures of faces showing all the emotional expressions except fear, as shown in drawings she made (see Figure 7-4).

FIGURE 7-4 Miss A could draw faces expressing all emotions except fear.

Human brain imaging studies also show that the amygdala is selectively activated by viewing faces showing fear. We think that the degree of response to the fearful faces may in part be genetic. People with one variant of a particular gene show greater activation of the amygdala than those without this gene variant. It appears that some 70 percent of Europeans and North Americans have the gene variant. Perhaps these people tend to be more fearful and less likely to get themselves into threatening or dangerous situations. They may be more “law-abiding.”

The selective role of the amygdala in fear would seem to make sense. It is a relatively old structure in the evolution of the brain. Fear is perhaps the most important emotion for survival of the individual in the primitive world. It was very important to detect cues to potentially dangerous situations. If you can’t learn to be afraid of man eaters, animal or human, you won’t survive. This would account for the key role of the amygdala for successful social behavior in monkeys. If you can’t learn to be afraid of the alpha male or if you are the alpha male and can’t detect fear in others, you are in trouble.

How does the visual information reach the amygdala? There are two visual systems in the brain, a primary system that leads to our awareness of seeing and a more ancient system that does not have access to awareness but does have access to the amygdala. We described the primary system and how it develops when we looked at critical periods in development (in Chapter 3). Information from the eye is sent (via the thalamus) to the primary visual area of the cerebral cortex and on to higher cortical areas. This is the system that allows us to see and identify objects in detail and be aware of doing so. If the primary visual cortex is destroyed, it causes complete blindness. Patients with such brain damage insist they are completely blind; they cannot “see” anything. But in fact they have “blindsight.” From Chapter 2 you may recall that such patients could accurately point to a source of light even though they claimed they could not see it. The pointing behavior is guided by a much more ancient visual system that does not have access to awareness.

This ancient visual system is well developed in lower animals such as the frog. Information from the eyes is projected to a visual structure in the lower brain, the visual midbrain. The frog does not have much cerebral cortex; its highest visual brain is the visual midbrain. This is the structure that guides the frog to strike its tongue accurately at a moving bug, much as our “blind” patient points accurately to the spot of light.

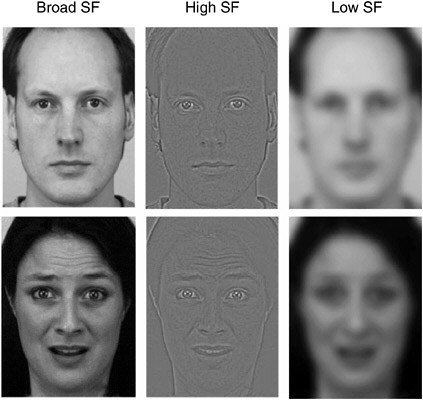

This ancient visual system has projections to the thalamus and the amygdala. Brain imaging studies show that the amygdala can be activated by fearful faces even if the person is completely unaware of seeing the faces at all, let alone identifying them as fearful (see Figure 7-5). The amygdala controls emotional re-

FIGURE 7-5 Photographs of normal (above) and fearful (below) faces with normal (broad) spatial frequencies (left), high spatial frequencies (middle), and low spatial frequencies (right). Broad and low pictures of fear “speak” directly to the amygdala.

sponses like palm sweating, as we saw earlier, which can occur in response to fearful stimuli even if the person is unaware. Shades of subliminal perception! The advertising industry is well aware of this fact.

In higher animals and humans, the primary visual system involves the visual cortex and the cortical face area (fusiform gyrus) responsible for detail vision of faces. However, the ancient midbrain visual system responds to much fuzzier pictures of faces, particularly fearful faces. A neutral face and a fearful face are shown in the left panel of Figure 7-5. The middle panel shows just the detailed outlines of the faces, and the right panel shows the fuzzy versions. Brain imaging indicates that the cortical face area responds better to the left and middle pictures, regardless of expression. On the other hand, the amygdala response to the fearful face is much greater for the intact face on the left and the fuzzy face on the right than to the detailed outlines in the middle panel.

Photography buffs will probably realize that the middle panel shows only higher spatial frequencies of the photographs on the left and that the right panel shows only lower spatial frequencies of the photographs. The key point here is that the amygdala can be activated by rapid and crude representations of potentially dangerous situations from the ancient midbrain visual system. This can occur more rapidly than the highly evolved cortical visual system that is so adept at perceiving details. The difference is only on the order of milliseconds (there are 1,000 milliseconds in a second), but this can be a huge advantage when responding to danger. The amygdala is on guard for potential threats and can rapidly trigger defensive actions. Note that in the classic painting of The Scream by Edvard Munch, shown in Figure 7-1, lower spatial frequencies predominate. Perhaps one reason this is such a powerful painting is that it speaks directly to the amygdala.

To return to Miss A, in another study she was compared to patients with severe amnesia, due to a different type of brain injury of the hippocampus who are more or less unable to remember their own experiences, as was true of patient HM (see Chapter 6). Miss A and the amnestics were given the test of facial expres-

sions of emotions. Again, Miss A was able to identify all the expressions except fear. On the other hand, the patients with amnesia correctly identified all the emotional expressions, including fear. After the testing was finished, Miss A and the amnestics were given a quiz to see how much they remembered about the faces. The amnestic patients were not able to remember much at all, but Miss A’s memory was excellent. Indeed, she can verbally describe her cognitive knowledge of what the word “fear” means; she just can’t experience it or perceive it in others. This raises a question: Are our perceptions of fearful faces due more to learning or more to innate genetic factors?

There are two different aspects to learned fears. One is the experience of being afraid, which involves the amygdala. Miss A is unable to experience fear. The other aspect is cognitive understanding of the meaning of fear. Miss A understands what the word “fear” means perfectly well. Amnestic patients also understand what the word means, but they can’t remember the fearful experience. Amnesia of the sort so extreme in HM does not involve damage to the amygdala but rather damage to the hippocampus and related structures.

So when we experience a situation that is fearful, both the amygdalar and hippocampal brain systems become engaged. The same is true for the lowly rat. When it is shocked in a distinctive cage and becomes afraid of the cage, both the hippocampus and the amygdala are necessary for the animal to remember the fear. Damage to either structure, particularly soon after the fearful exposure, will abolish the fear memory.

Human brain imaging studies of normal people being shown faces expressing various emotions seem to indicate that different emotions involve different brain areas. As we noted, the amygdala is consistently activated when normal people view faces expressing fear. A perception of sadness involves the amygdala to some degree and a cortical region of the temporal lobe, and a perception of anger activates two frontal cortical regions (orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate). It seems that the amygdala is also sensitive to the direction of gaze. If the role of the amygdala is to detect threat

of danger, it should respond more to a fearful expression directed to the subject rather than away, but the opposite might be true for anger. In one study, at least, the amygdala was activated much more by angry faces looking away from the subject than if looking directly at the subject.

Perception of disgust is particularly interesting. It selectively activates the striatum (also called the basal ganglia). This structure is severely damaged in some brain disorders, including Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease. The latter is a progressive and severe genetic disorder leading ultimately to death. It is due to a single dominant abnormal gene (see Chapter 5). The sufferer typically does not show any symptoms until about age 40. For this reason a person with the abnormal gene may not know he has it unless he has been tested for it. People who have the abnormal gene but who have not yet exhibited any symptoms are termed carriers. Huntington’s patients appear to be selectively unable to recognize facial expressions of disgust. Remarkably, even carriers also seem to be unable to recognize the expression of disgust. These rather surprising discoveries suggest that different emotions have very different evolutionary histories, as do the brain regions that seem to code them.

Interestingly, negative emotions display much more consistent patterns of brain activation than positive emotions. Results of brain imaging studies of people viewing happy faces have been inconsistent. Light was shed on this question in a study at Stanford University. People were rated on their degree of extroversion and then imaged while viewing happy faces. People who were rated high on extroversion showed much greater activation of the amygdala than did less extroverted individuals. The relationship of this finding to the well-established role of the amygdala in fear remains to be determined.

The amygdala indeed plays a special role in emotional memories. In a study done by Larry Cahill, James McGaugh, and colleagues at the University of California, Irvine, normal adults were exposed to a video composed of neutral film clips and one composed of emotionally arousing clips (animal mutilations and vio-

lent crimes). Brain images were taken during the viewing of the videos. Three weeks later the subjects were given memory quizzes. They remembered many more details of the emotional films, as expected. Importantly, there was a high correlation (positive relationship) between the amount of activation in the amygdala and the amount of material remembered from the emotional video but no correlation for the neutral video.

Studies like this one raise the possibility that the amygdala is the key structure in flashbulb memories. But what are the mechanisms and where are the memories stored? We must take a brief look at studies of emotional memory storage in animals. The basic association between neutral stimuli and fear-inducing stimuli, and the expression of this learned fear, as in freezing in rats and increased heart rate, sweating, and muscle tension in humans, critically involves the amygdala, as we saw earlier. But what about all the memories associated with fearful events?

Hormonal Effects on Fearful Memories

When animals and humans are emotionally stressed and experience fear, a well-understood series of hormonal events occur. The end result is release by the adrenal gland of adrenaline, the “arousal” hormone, and “corticosterone,” the stress hormone. These hormones exert actions on the brain. We focus here on adrenaline. If rats are given fear training using electric shock, there is a marked rise in adrenaline following the experience. Later, where the rats are tested for their memory of the event, they typically show excellent memory. Indeed, the amount of increase in adrenaline release at training is directly related to the strength of the later memory.

In an important series of studies, James McGaugh and his colleagues showed that if rats were trained in a simple fear task using a moderately intense shock and were injected with adrenaline (into the bloodstream) after the learning experience, the rats later remembered the experience much better than control animals that received injections of a neutral salt solution. Since the drugs

are injected after the learning experience, they can’t act directly on the experience. Similarly, since they are injected well before the memory test, they can’t act on the performance of the animals at the time of the test. The drug must somehow be acting on the brain to enhance or “stamp in” the memory of the initial experience.

This phenomenon, termed memory consolidation, is very general. As we saw earlier, emotions that occur in association with traumatic events can markedly enhance later memories of the events, as in flashbulb memories. The increased release and actions of the hormones occur well after the emotional event; they have a much slower time course than the actual experience of the events.

To return to McGaugh’s studies, he and his colleagues were able to show that the actions of adrenaline and other memory enhancers are on the amygdala. There is a very high concentration of one type of adrenaline receptor in the amygdala, termed the beta-adrenergic receptor, which we will refer to as the beta A receptor. Receptors in the brain are tiny structures on the surface of nerve cells made of proteins. Only one kind of brain chemical or hormone can act as a given kind of receptor—the chemical molecule fits into the receptor like a key in a lock and causes certain reactions in the nerve cells. A particular hormone like adrenaline acts on several different types of receptors, each causing a different action on the neuron. Here we focus on the beta A receptor acted on by adrenaline on neurons in the amygdala.

If the brain form of adrenaline is injected directly into the amygdala after fear training in rats, the same enhanced consolidation of memory occurs as with injections of adrenaline into the bloodstream. Further, if a drug is injected into the amygdala that blocks the beta A receptors, so that the brain form of adrenaline can no longer act on this receptor in the amygdala, both the memory-enhancing effects of adrenaline injected into the bloodstream and the similar effects of direct injections into the amygdala are blocked. The blocking drug’s molecules also fit into the beta A receptors, much like adrenaline, and remain on the

receptors, so adrenaline can’t attach to them. But when the blocking drugs attach to the receptors, the receptors do not exert any actions on the neurons.

In a dramatic study, Cahill and McGaugh blocked the beta A adrenaline receptors in one group of human volunteers by injecting a beta A receptor blocking agent (called propranolol) into the bloodstream when the volunteers were experiencing a very emotional story or a neutral story. Control volunteers received an injection of an inactive substance (placebo). The two stories, accompanied by the same set of slides, are shown in Box 7-1. The placebo control group remembered details of the emotional part of the story much better than the corresponding part of the neutral story. But the subjects given the beta A blocker did not. They remembered both versions of the story at the same level as the placebo group remembered the neutral story. There was no memory enhancement of the emotional part of the story when the beta A receptors were blocked, presumably in the amygdala, judging by the animal studies.

These experiments provide us with a rather compelling explanation of the brain mechanisms involved in flashbulb memories. Following emotional experiences there is an increase in release of arousal and stress hormones that act on the amygdala to enhance the storage of memories in the amygdala and at various other places in the brain.

As a further validation of this idea, Cahill and McGaugh had the opportunity to study a patient in Germany suffering from Urbach-Weithe disease, which destroys the amygdala. They gave the German translation of the emotional story shown in Box 7-1 to him and also to normal individuals. The control people showed the expected memory enhancement of the emotional part of this story, but the patient did not.

Anxiety

We have all experienced feelings and symptoms of anxiety in this “age of anxiety.” Indeed, we could not function adequately in our

complex contemporary society without feelings of anxiety. But taken to the extreme, such feelings become anxiety disorders. In psychiatry there are three general categories of anxiety disorders: phobias, post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD), and anxiety states. All three have similar emotional-physiological symptoms, which closely resemble the symptoms exhibited by animals trained in conditioned fear (Table 7-1). Indeed, much of what we have said about learned fear applies to human anxiety. Phobias and PTSD clearly involve learning. However, the picture is not so clear in anxiety states.

Phobias

Phobias, ranging from fear of crowds to fears of specific objects and animals, are thought to be due to traumatic learning experiences in childhood, examples of Pavlovian conditioning. Consider the following case history:

A young woman developed during her childhood a severe phobia of running water. She was unable to give any explanation of her disorder which persisted without improvement from approximately her seventh to her twentieth year. Her fear of splashing sounds was especially intense. For instance, it was necessary for her to be in a distant part of the house when the bathtub was being filled for her bath, and during the early years it often required the combined efforts of three members of the family to secure a satisfactory washing. She always struggled violently and screamed. During one school session a drinking-fountain was in the hall outside her classroom. If the children made much noise drinking, she became very frightened, actually fainting on one occasion. When she rode on trains, it was necessary to keep the shade down so that she might not see the streams over which the train passed. (When she was 20 years old an aunt visited her and, upon hearing of her condition responded: “I have never told.” This provoked a recall of the following events that took place when she was seven years of age.) The mother, the aunt, and the little girl … had gone on a picnic. Late in the afternoon, the mother decided to return home but the child insisted on being permitted to stay for a while longer with her aunt. This was promptly arranged on the child’s promise to be strictly obedient and the two friends (aunt and niece) went into the woods for a walk. A short time later the little girl, neglecting her agree-

|

BOX 7-1

|

ment, ran off alone. When she was finally found she was lying wedged among the rocks of a small stream with a waterfall pouring down over her head. She was screaming with terror. They proceeded immediately to a farm house where the wet clothes were dried, but, even after this the child continued to express great alarm lest her mother should learn of her disobedience. However, her aunt reassured her with the promise “I will never tell….”

This case is unusual in one regard—the traumatic event was identified. In many cases of specific phobias the initial learning experience cannot be identified. This is not so much a case of

|

repression as it is interference by repeated experiences. How do you remember the first time you were scared by a snake (or running water) if it has happened many times?

Since phobias are in large part learned, they should be treatable by applying what is known about learning, particularly forgetting. Indeed, successful treatments of specific phobias involve procedures to induce extinction, to reduce and “extinguish” Pavlovian conditioned responses. When a rat is trained to fear by pairing a tone with a shock, the tone fear-freezing response is extinguished by presenting the tone over and over again with no shock. Eventually, the animal stops freezing. In treating humans

for phobias, this process of extinction is called desensitization. But conditioned fear in humans to certain phobic objects like snakes does not extinguish readily.

Albert Bandura at Stanford University has developed procedures for extinguishing phobias that make use of desensitization but also emphasize the person’s cognitive awareness of feelings. In a classic study he compared simple desensitization by repeatedly exposing the “clients” (suffering from snake phobias) to desensitization together with modeling (acting out) the behavior only by the therapist and by the therapist and the client, with a focus on personal feelings of efficacy.

We conducted a series of experiments in which severe phobics received different types of treatments designed to raise their sense of personal efficacy. We selected adults who suffered from severe snake phobias. Virtually all had abandoned outdoor recreational activities. Some could not pursue their vocational work satisfactorily. The most pervasive effect of the phobia was thought-induced distress. Most of the participants were obsessed with reptiles, especially during the spring and summer, frequently dreaming of snake pits and being encircled or pursued by menacing serpents.

To begin, we asked our clients to perform as many tasks as they could with a snake—looking at it caged, touching it, holding it, and so on. For each task, they rated their perceived self-efficacy, which was extremely low. Indeed, may clients refused to enter the room, let alone interact with the snake.

During the treatment phase, one group of clients was aided through participant modeling to engage in progressively bolder interactions with a snake until they had mastered their fear. A second group merely observed the therapist modeling the same activities with the snake, relying solely on vicarious experience to alter their efficacy expectations.

After their respective treatments, we measured the clients’ perceived self-efficacy and behavior toward different types of snakes. We found that treatment based on performance mastery produces higher, more generalized, and stronger efficacy expectations than treatment based on vicarious experience alone. In both treatments, behavior corresponds closely to self-perceived

efficacy. The higher the sense of personal efficacy, the greater were the performance attainments.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

This kind of anxiety stands in contrast to phobias in that the traumatic experience is too well remembered and cannot easily be forgotten:

Jim Griggs is a twenty-six year old married Vietnam veteran recently laid off from a job he had held for three years. He was admitted to the hospital for severe symptoms of anxiety, which began after he was laid off at work and found himself at home watching reports of the fall of South Vietnam on TV. When asked what was wrong with him, he replied, “I don’t know. I just can’t seem to control my feelings. I’m scared all the time by my memories.” Jim described himself as well adjusted and outgoing prior to his service in Vietnam. He was active in sports during high school. He was attending college part-time and working part-time to pay his way when he was drafted to serve in Vietnam. Although he found killing to be repulsive initially, he gradually learned to tolerate it and to rationalize it. He had several experiences that he found particularly painful and troubling. One of these occurred when he was ambushed by a Vietnamese guerrilla, found his gun had jammed, and was forced to kill his enemy by bludgeoning him over the head repeatedly. Many years later he could still hear the “gook’s” screams. Another extremely painful incident occurred when his closest friend was killed by mortar fire. Since they were lying side by side, the friend’s blood spattered all over the patient.

Although he had some difficulty adjusting during the first year after his return from Vietnam, drifting aimlessly around the country in Easy Rider fashion and finding it difficult to focus his interests or energies, he eventually settled down, obtained a steady job, and married. He was making plans to return to college at the time he was laid off. At home with time on his hands, watching the fall of Vietnam on TV, he began to experience unwanted intrusive recollections of his own Vietnam experiences. In particular, he was troubled by the memory of the “gook” he had killed and the death of his friend. He found himself ruminating about all the people who were killed or injured and wondering what the purpose of it all had been. He began to experience nightmares, during which he relived the moments

when he himself was almost injured. During one nightmare, he “dived for cover” out of bed and sustained a hairline fracture of the humerus (arm). Another time he was riding his bike on a path through tall grass and weeds, which suddenly reminded him of the terrain in Vietnam, prompting him to dive off the bike for cover, and causing several lacerations to his arms and legs when he hit the ground. He also became increasingly irritable with his wife, and was admitted to the hospital because of her concern about his behavior.

Jim’s symptoms are common in PTSD: reliving, reexperiencing, and flashback episodes. In flashbacks the reliving may be so intense that the person is, in his mind, back in the stressful episode. In Jim’s case a combination of antianxiety drugs and desensitization training, repeatedly recalling and reliving his traumatic experiences in Vietnam, proved helpful.

It has become standard practice in the United States to provide grief counseling to people immediately after extremely traumatic events such as high school shootings. In the wake of the terrorist attacks at the World Trade Center on 9/11/01, more than 9,000 counselors and therapists descended on New York City to offer aid and comfort to families and surviving victims. These therapists believed that many New Yorkers were at high risk of developing PTSD.

The most widely used method to counter the effects of a trauma is psychological debriefing, talking about the traumatic events as soon as possible. You may be surprised to learn that what evidence exists suggests that such interventions are of no help at all and may even interfere with normal recovery. People vary widely in their vulnerability to trauma. The vast majority of trauma survivors do not develop PTSD.

A remarkable new treatment for PTSD has been developed, based on basic research. We saw earlier that the drug propranolol which blocks the beta A receptor prevents the enhancement of memory of emotional or traumatic stories. A group in the psychiatry department at Harvard Medical School used this drug to treat PTSD. The drug (or a placebo) was administered to a large group of patients in the emergency room who had just experi-

enced a traumatic event. The patients who received the drug showed a marked reduction in PTSD symptoms compared to those who received the placebo!

Anxiety States

Two major forms of anxiety states are panic attacks and generalized anxiety. With panic disorder, a person suffers sudden and terrifying attacks of fear that are episodic and occur unpredictably. The symptoms of a panic attack are dilated pupils, flushed face, perspiring skin, rapid heartbeat, feelings of nausea, desire to urinate, choking, dizziness, and a sense of impending death (see Table 7-1). Generalized anxiety disorder is a persistent feeling of fear and anxiety not associated with any particular event or stimulus.

Recent evidence suggests that both panic attacks and generalized anxiety have a significant genetic basis. Interviews of relatives of anxious patients in clinical studies indicated that up to 40 percent of the relatives also have had anxiety neurosis. It is tempting to postulate that anxiety states are learned: A person who grows up in a neurotic family seems likely to resemble the rest of the family in mental disposition. However, studies of twins show that if one identical twin has anxiety neurosis, the chances are greater than 30 percent that the other will too, whereas the chances of both twins having the disorder are only about 5 percent if they are not identical. Isolated cases in which one identical twin was adopted away from the family and the twins were raised separately show the same general result. But environmental factors (learning) also must be important.

In the mid-1930s dye compounds attracted the attention of chemists at the pharmaceutical company Hoffman-La Roche. The chemists were attempting to make a particular group of dye compounds biologically active. Unfortunately, the compounds they made did not seem to have any biological activity. The compounds were put aside, as were others. By 1957 the laboratory benches had become so crowded that a cleanup had to be instituted. As the chemists were throwing out various drugs and other compounds,

one drug was submitted for pharmacological tests. It had extraordinary calming and muscle relaxant effects in animals. When the chemists analyzed the structure of the drug, it turned out to be a rather different compound than they thought they had made. It was, in fact, the substance that came to be known as Librium.

The discovery of Librium and other minor tranquilizing (antianxiety) drugs provided an intriguing new approach to understanding the anxiety neuroses. These drugs are all closely chemically related and are a class of compounds called the benzodiazepines (BDZ).

Antianxiety drugs are the treatment of choice for panic attacks and anxiety. In proper therapeutic doses they are relatively safe, have few side effects, and are not particularly addictive. In higher doses they are addictive, both in terms of tolerance that is built up (increasingly high doses are required to produce the same effect) and the variety of symptoms that follow withdrawal, including anxiety and emotional distress, nausea and headaches, and even death. Antianxiety drugs have also become drugs of abuse.

Antianxiety drugs ease anxiety and panic attacks. They are of little help in treating schizophrenia, even for treating the anxiety symptoms associated with the disease, and they may even make depression worse. Interestingly, they are not particularly helpful in the treatment of specific phobias, although they may be helpful in PTSD. These antianxiety drugs act very specifically on the brain. They enhance inhibitory processes in neurons, leading to a general decrease in brain activity.

There are many different chemical forms of BDZs. Indeed, the tranquilizer of choice varies from year to year. They all act to enhance inhibition of neurons in the brain. Hence, it might be expected that they can impair memory formation and indeed they do. Specifically, they interfere with long-term encoding of new episodic information—memories of our own experiences—but not with already established memories. They have little effect on memories for general knowledge (semantic memory) or on nondeclarative types of memory. Interestingly, the amnestic ef-

fect is not correlated directly with the sedative effects of these drugs.

Some BDZs have particularly powerful effects on episodic memory formation. Rohypnol, sometimes referred to as the “date rape drug” is a case in point. It induces drowsiness and sleep and is powerfully amnestic. Furthermore, it is water soluble, colorless, odorless, and tasteless. It can be slipped into a drink and afterwards the victim may be completely unable to remember anything that has occurred, including sexual assault. A number of such unfortunate cases have been reported. Fortunately, the drug is now illegal.

The Brain Reward System

Identification of the “reward system” in the brain is one of the most important findings yet about the brain and learning. It was discovered by a brilliant psychologist, James Olds, at the beginning of his career when he was working as a postdoctoral fellow in the laboratory of Donald Hebb, a pioneer in the study of the brain and memory, in Montreal. As Olds said, he arrived at Hebb’s laboratory, only to be given a key to a storage area in the basement where pieces of wood and old equipment were kept. He had the impression Hebb would return a few months later to see what he might have discovered.

In a series of experiments, Olds and a graduate student, Peter Milner, discovered the brain reward system. They implanted small electrodes in different regions of the brains of rats under anesthesia and later, when the animals were awake, delivered mild electric shocks to the brains. When the electrodes were in certain places in the brain, the rats liked it. If they hooked up a lever so that a rat could deliver a shock to its own brain, the rat would press the lever as fast as it could to get those “fixes” (shocks). In a particularly “hot” spot in the brain, the rat would press the lever as much as 2,000 times in an hour! Electrodes have been implanted in this same brain system in a few human patients. They find it difficult to describe the sensations, except that

the brain stimulus feels intensely pleasurable and they want more of it.

The brain reward system is a neuronal pathway from neurons in the brain stem that projects to forebrain structures, particularly the prefrontal area of the cerebral cortex and a structure called the nucleus accumbens in the brain (see Figure 7-6). The neurons in this reward pathway use dopamine as their chemical synaptic transmitter; that is, they release dopamine to act on neurons in the forebrain. Electrical stimulation of this pathway in animals by the experimenter to elicit pleasure causes the release of dopamine on neurons in the cortex and accumbens.

Stimulation of this brain reward system in rats serves as a powerful reinforcement for learning. Such brain stimulation can be even more effective than food or water in teaching the animals any particular task. They will learn and do almost anything to get their electrical brain fix.

This reward system in the brain is, of course, strongly activated by normal rewards. Thus, food for a hungry rat, water if thirsty, or a sex partner causes marked release of dopamine from the brain reward pathway on to neurons in the accumbens. The great unknown in this story of reward learning is how the associations between neutral stimuli and situations and appropriate behaviors become greatly strengthened with activation of the brain reward system, that is, how reward learning occurs. This is an important question for future research since so much of the learning people do involves rewards.

Drug Abuse

A remarkable fact about addictive drugs is that, to the extent studied, they all strongly activate this brain reward system. Cocaine and amphetamines (speed, crack) act primarily on this brain system but also on the amygdala. The opiates (morphine and heroine) act on this brain reward system, on the amygdala, and on other brain systems. Alcohol acts on this brain reward system and on a number of other brain systems as well.

There are three major aspects to drug addiction: addiction itself, tolerance, and withdrawal. Addiction is really a behavioral term—the user seeks out and takes a substance with increasing frequency. Cravings, which increase after repeated use, are a large part of the reason for this behavior. We use the term tolerance to mean that increasing doses of the drug must be taken to achieve the desired effect. Finally, withdrawal refers to the very unpleasant symptoms, including intense cravings, that develop when the user stops taking the substance.

These phenomena of drug addiction profoundly involve learning. Behavioral tolerance is a good example. Substantial tolerance develops with repeated use of heroin. In rats, tolerance is so extreme that a dose that would kill a rat new to the drug is easily tolerated by addicted rats (yes, rats can become just as addicted as people). Furthermore, much of this tolerance is actually learned to be associated with the environment where the drug is given. A dose of heroin that is safe for the addicted rat in the environment where the drug normally is given will kill the same rat in a different environment. This phenomenon of learned tolerance may account for some human overdose deaths—for example, if an addict takes the high dose to which he has become tolerant in a different and unusual environment.

Craving is learned. It appears that the memories relating to the effects of the drug are transformed into craving for the drug in the amygdala. Imagine a drug user who usually buys cocaine at a particular subway stop. This stop is normally a neutral part of the environment. But it becomes linked in the mind of the user to the positive rewarding effects of cocaine. Even long after rehabilitation, sight of this subway stop can bring on a powerful craving for cocaine. The same is true for nicotine addiction. Circumstances where the smoker usually lit up, like with the first cup of coffee in the morning, can elicit cravings for cigarettes a year after quitting. In animal studies, lesions of the amygdala appear to block cravings. Recall that the amygdala is critically involved in learned fear and anxiety, feelings not too different from the unpleasant aspects of cravings experienced by the addict.

Alan Leshner, then director of the National Institute of Drug Abuse, stresses the fact that drug addiction is a disease:

Scientific advances over the past 20 years have shown that drug addiction is a chronic, relapsing disease that results from prolonged effects of drugs on the brain…. Recognizing addiction as a brain disorder characterized by … compulsive drug seeking and use can impact society’s overall health and social policy strategies and help diminish the health and social costs associated with drug abuse and addictions.

The addict is not simply a weak or bad person, but rather a person with a brain disease.

EMOTIONS AND ETHICS

Many people believe that science has no place in moral and ethical matters. Indeed, many moral philosophers and ethicists maintain that moral decisions must be based on pure reason. However, it seems obvious that the moral and ethical views that people hold are learned. Factors that underlie moral values include brain systems involved in learned feelings and emotions. Indeed, recent imaging studies of brain regions involved in emotions seem to cast light on some aspects of moral decisions.

Consider the following moral dilemma:

You see a streetcar careening out of control, headed toward the edge of a cliff. There are five terrified people on board, and all will be killed unless you do something. As it happens, you are standing beside a switch that will send the streetcar onto another track and all will be saved. But, unfortunately, there is someone standing on the other track who would then be killed. (We know, it’s a little unrealistic, but philosophers seem to like such scenarios.) So the question is, should you sacrifice one person to save five people? Most people think you should. But suppose now that there is no other track, and the only way you can stop the streetcar is to push a very heavy person onto the track in front of the on-rushing vehicle. This person would, of course, be killed. Most people think it would be wrong to stop the streetcar in this manner.

There is no logical reason why one outcome should be preferred over the other. Why is it OK to kill one person to save five

in some circumstances but not others? A group at Princeton University imaged brain activity in people who read and reasoned their way through a number of scenarios of each type. In the body-pushing situations, areas of the brain particularly involving sadness and other emotions showed increased activation, but this did not happen in the switch-pushing situations. People felt much more emotional distress in the body-pushing situations, due in turn to learning, which accounts for their moral judgments. The outcomes are identical in that five people are saved and one is killed, but they differ in that only one course of action feels really wrong. So perhaps psychology and neuroscience will someday supplant philosophical approaches to morality and ethics.