Finding Hazardous Asteroids Using Infrared and Visible Wavelength Telescopes (2019)

Chapter: 3 Current and Near-Term NEO Observation Systems

3

Current and Near-Term NEO Observation Systems

When sunlight hits an asteroid’s surface, it both reflects photons and absorbs them to emit their energy in the infrared. Astronomers use telescopes to amplify the light in the night sky combined with sensors designed to detect signals at wavelengths carrying pertinent information about the target under study. This chapter describes the systems for near Earth object (NEO) detection and characterization and explains the value of searching for NEOs while simultaneously characterizing them using a space-based platform.

NEO OBSERVATION ASSETS: PAST, PRESENT, AND NEAR FUTURE

In the past 23 years, the search for NEOs has been dominated by ground-based, visible-wavelength telescope systems. These systems are described briefly below.

- Lincoln Near-Earth Asteroid Research (LINEAR) program.1,2,3 The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Lincoln Laboratory LINEAR asteroid search program began in 1998. Between 1998 and 2013, the program used two 1-meter, ground-based, visible-wavelength telescopes located near Socorro, New Mexico, to detect asteroids. In 2013, the program transitioned to using the Space Surveillance Telescope (SST) at White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico. The program has since continued as a joint operation between MIT Lincoln Laboratory, NASA, and the U.S. Air Force. In 2017, ownership of SST was transferred to the Air Force. The telescope is currently undergoing relocation to Western Australia, where it is expected to resume operations—possibly including the search for NEOs—in the early 2020s.

___________________

1 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Lincoln Laboratory, 2019, “On The Watch for Potentially Hazardous Asteroids,” https://www.ll.mit.edu/impact/watch-potentially-hazardous-asteroids.

2 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Lincoln Laboratory, 2019, “Space Surveillance Telescope,” https://www.ll.mit.edu/r-d/projects/space-surveillance-telescope.

3 J.D. Ruprecht, G. Ushomirsky, D.F. Woods, H.E.M. Viggh, J. Varey, M.E. Cornell, G. Stokes, 2015, “Asteroid Detection Results Using the Space Surveillance Telescope,” paper presented at the American Astronomical Society, DPS meeting #47, id.308.02, https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/1001992.pdf.

- Near-Earth Asteroid Tracking (NEAT) program.4,5,6 The NEAT program, operated between December 1995 and April 2007, was a collaboration between NASA, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), and the Air Force. The monthly automatic search program used three 1-meter aperture, ground-based, visible-wavelength telescopes (two located in Hawaii and one at Palomar Observatory in southern California).

- Spacewatch.7 Spacewatch is the small object—including NEOs—observing program of the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. The program began in 1980 and since 1998 has focused on follow-up astrometry of targets, focusing on the orbits of those objects that may present a hazard to Earth. Observations are made using two ground-based, visible-wavelength telescopes with 0.9-meter and 1.8-meter apertures located at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona.

- Lowell Observatory Near-Earth Object Search (LONEOS).8,9,10 LONEOS was an NEO-detection program run by Lowell Observatory between July 1998 and February 2008. The project used a 0.6-meter-aperture, ground-based, visible-wavelength telescope located at Anderson Mesa near Flagstaff, Arizona, to conduct the survey with observations happening on average 200 nights per year.

- Catalina Sky Survey (CSS).11 CSS, founded in 1998 and operated by the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, is an ongoing program to detect and track NEOSs with diameters larger than about 140 meters in order to assist completion of the George E. Brown Act requirements. CSS utilizes ground-based, visible-wavelength telescopes with apertures of 0.7, 1.0, and 1.5 meters located in Arizona, two for discovery and two for follow up.

- Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS).12,13 Pan-STARRS is a fully operational astronomical imaging system designed and run by the Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii. The system has been in operation since 2010 and uses two 1.8-meter ground-based, visible-wavelength telescopes on Maui, Hawaii (see Figure 3.1). Pan-STARRS 2 only began operations in 2018.

- Asteroid Terrestrial-Impact Last Alert System (ATLAS).14 The ATLAS system, developed by the University of Hawaii, was funded in 2013 and began detecting asteroids in 2015. The system is composed of two 0.5-meter ground-based, visible-wavelength telescopes located in Hawaii 100 miles apart. The survey views the whole sky several times each night.

- Zwicky Transient Facility at Palomar. This telescope is serendipitously finding a modest number of asteroids, despite not being funded for that purpose by NASA.15

There have been far fewer space-based NEO surveys, including the following:

- NEOWISE.16 NEOWISE, funded by NASA’s Planetary Science Division, leverages the Wide-Field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) space-based, infrared telescope, which ended its primary mission in 2010. NEOWISE operated from September 2010 until February 2011. Observations were halted until December 2013, when the telescope was reactivated; observations continue to the present as the NEOWISE Reactivation Survey (see Figure 3.2). The survey’s lifetime is governed by the spacecraft’s evolving orbit, and predictions of when the survey will cease to provide useful data are uncertain.

___________________

4 S.H. Pravdo, D.L. Rabinowitz, E.F. Helin, K.J. Lawrence, R.J. Bambery, C.C. Clark, S.L. Groom, et al., 1999, The Near-Earth Asteroid Tracking (NEAT) Program: An automated system for telescope control, wide-field imaging, and object detection, The Astronomical Journal 117:1616-1633.

5 Ibid.

6 T. Morgan, 2019, Near Earth Asteroid Tracking V1.0, NASA, urn:nasa:pds:context_pds3:data_set:data_set.ear-a-i1063-3-neat-v1.0.

7 T. Bowell and B. Koehn, 2008, “The Lowell Observatory Near-Earth-Object Search,” last modified April 1, https://asteroid.lowell.edu/asteroid/loneos/loneos.html.

8 T. Bowell and B. Koehn, 2004, “About LONEOS,” last updated July 23, https://asteroid.lowell.edu/asteroid/loneos/loneos1.html.

9 T. Bowell and B. Koehn, 2000, “Searching for Near-Earth-Objects,” last updated May 30, https://asteroid.lowell.edu/asteroid/loneos/loneos2.html.

10 T. Bowell and B. Koehn, 2008, “LONEOS Asteroid Observations,” last updated December 16, https://asteroid.lowell.edu/asteroid/loneos/public_obs.html.

11 University of Arizona, 2019, “About CSS,” https://catalina.lpl.arizona.edu/.

12 See http://pswww.ifa.hawaii.edu/pswww/.

13 See the University of Hawaii Pan-STARRS1 data archive home page at https://panstarrs.stsci.edu/.

14 University of Hawaii, “ATLAS Project: Asteroid Terrestrial-Impact Last Alert System (ATLAS),” http://atlas.fallingstar.com/home.php.

15 NASA also funded NEA searches with the Dark Energy Camera on the 4-meter Blanco Telescope in Chile between 2014 and 2016.

16 California Institute of Technology, 2019, “The NEOWISE Project,” https://neowise.ipac.caltech.edu/.

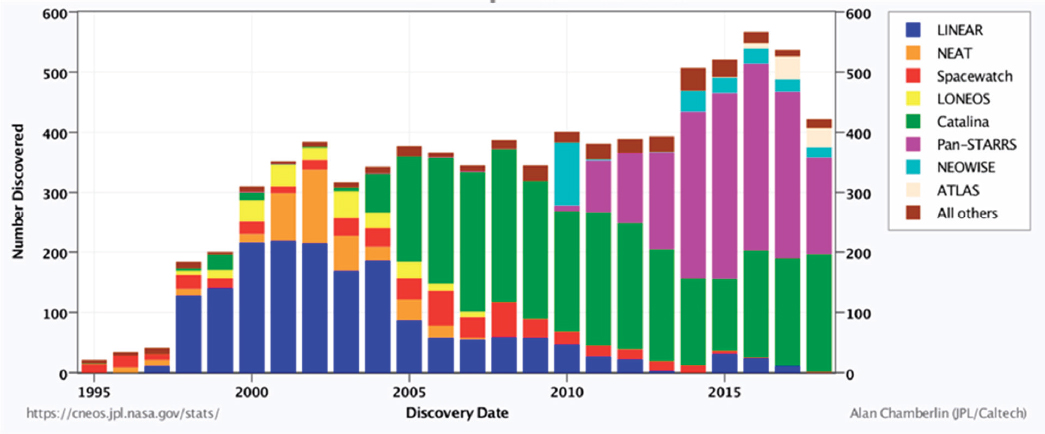

Over time, NEO surveys have used larger telescopes that have more sensitive detectors and observe larger regions of the night sky. As a result, the rate of NEO discoveries over the past 20 years has risen steadily, to the point where more than 2,000 NEOs were discovered in 2017 alone—two orders of magnitude more annual discoveries than in 1995. The impact of adding new, complementary telescopic search programs can be seen in the increase of the number of new NEOs discovered as systems have come online over time (see Figure 3.3).

CSS and Pan-STARRS are both extending the number of discoveries and finding smaller objects. Figure 3.4 shows the impact of the CSS and Pan-STARRs surveys contributing to the discovery rate of objects >140 meters.

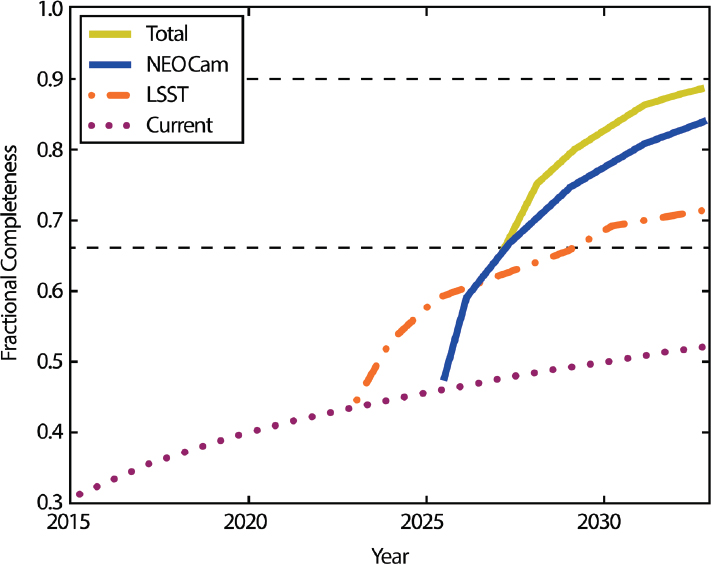

As shown in Figure 3.5, current NEO survey systems will not satisfy the George E. Brown Act goals regardless of how long they operate.

PROJECTIONS FOR LSST

Ground-based telescopes continue to add to our inventory of NEOs, as seen by the steep slopes of the cumulative numbers of NEOs discovered larger than 140 meters in Figure 3.5. This trend will continue into the future, particularly as new ground-based telescopes come online.

Of particular importance to the ground-based NEO search, the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST)17 is scheduled to come online in 2023. Located in Chile, it will conduct a 10-year baseline survey using an 8.4-meter mirror (see Figure 3.6). One of LSST’s four science goals is to observe the solar system. The other three goals are astrophysical: understanding dark matter, exploring the changing sky, and tracking motions of stars in the Milky Way galaxy. The planned operations will find many more NEOs, but the accuracy of the diameter measurements is not as good as that determined by infrared observations and will not reach the completeness requirements of the George E. Brown Act. LSST’s contributions to NEO survey goals have been modeled, yielding the following results:

- If the contributions of NEO search efforts from their inception in the early 1990s to the present are included, the LSST will result in an NEO catalogue for objects with an absolute brightness, or H value, of less than 22, which is 75 percent complete by the end of its 10-year baseline survey. (As mentioned later in this report, diameter estimates from visible observations at the LSST will have very large uncertainties due to the unknown albedo of a given object.)

___________________

17 National Science Foundation, 2019, “Mirror, Mirror on the Mountain—LSST Primary/Tertiary Mirror (M1M3) Arrives on Cerro Pachón,” May 11, https://www.lsst.org/news/mirror-mirror-mountain.

- The astrometric accuracy of the positions obtained by the LSST will be on the order of 50 milli-arcseconds (mas) due to use of the Gaia star catalogue and the large number of catalogue stars per image frame.18 These measurements result in accurate orbital calculations for the detected NEOs.

At the same time that LSST will contribute to the NEO search and discovery, photometric measurements obtained by the telescope can be used to infer diameter estimates that have larger uncertainties than those derived from infrared measurements. LSST diameter estimates are derived from the absolute magnitude (H) from visible photometry and an assumed geometric albedo.19 Unfortunately, catalogue H values are notoriously unreliable (see,

___________________

18 A milli-arcsecond (mas) is one-thousandth of an arc-second, and equals 1/3,600,000th of a degree. It is an angular unit of measure used to describe the apparent size of an object in space as viewed from a telescope either on the ground or in space.

19 The relationship between size, geometric albedo (pV), and absolute visual brightness (H) is: D = 10−H/5 × 1329/![]() km.

km.

for example, Pravec et al. [2012]20) with errors of up to 0.5 mag or more, depending on the brightness of the object. This problem will probably worsen as smaller (fainter) objects are discovered in future surveys, with a consequent increase in the uncertainty of diameters derived from visual observations. It should be noted that H values are not required for the derivation of diameters from thermal-infrared observations and cannot be provided by the latter. As previously noted, the extreme range for visual albedos is 0.01 to 0.5, whereas the more typical visual geometric albedo (pV) values are between ~0.02 and ~0.35 for well-observed NEOs in the size range greater than ~1 kilometer, and this albedo distribution is assumed to be the same for small NEOs. Under these assumptions, a random NEO LSST discovery with H = 22 will have a diameter between 90 and 375 m. Assuming full multicolor photometry is available, these limits can be reduced to a size range of about 140 to 240 m. Surveys at visual wavelengths are biased against discovering low-albedo objects. A LSST survey starts to become significantly incomplete fainter than H = 21 (Jones et al. 2017); it is likely that many of the missing H = 22 NEOs in visual surveys will have albedos closer to 0.02 than to 0.35. LSST can detect objects fainter than H = 22, but only a fraction of these low-albedo NEOs will be discovered at higher values of H (fainter). Their relatively high infrared fluxes favor detection with an infrared telescope, which is also the preferred method to provide accurate diameters. In this regard, ground- and space-based telescopes are synergistic.

The committee heard from experts on LSST who informed the committee that LSST would be 50-60 percent complete on H < 22 NEOs in 10 years. When combined with other search efforts, this would be approximately

___________________

20 P. Pravec, A.W. Harris, P. Kušnirák, A. Galád, and K. Hornoch, 2012, Absolute magnitudes of asteroids and a revision of asteroid albedo estimates from WISE thermal observations, Icarus 221:365-387.

77 percent. The committee was also informed that even a second dedicated LSST would not achieve the George E. Brown Act goals, and the committee determined that any additional LSST-class telescope would take up to a decade or more to make operational.21

Finding: No existing ground- or space-based platform can satisfy the size and completeness requirements of the George E. Brown Act goals in the foreseeable future.

Finding: It might be possible to build a ground-based telescope that could satisfy the completeness requirement of the George E. Brown Act if operated for a very long time (i.e., many decades). However, such a telescope would not meet the goals for size measurements. A new, dedicated, space-based infrared survey mission is required to achieve the George E. Brown Act goals.

Finding: The LSST will find many NEOs, despite the fact that this is only one of the telescope’s four goals. However, it will not achieve the George E. Brown Act goals. Even an LSST dedicated to finding NEOs would not achieve the George E. Brown Act goals alone, or even in combination with other current ground-based assets.

Discovery observations provide positions for determining orbits and estimates of either diameter (for thermal infrared systems) or absolute magnitudes (H, for visual systems). Additional observations for physical characterization—for example, to determine composition and estimate density—must be obtained by nonsurvey assets. This is because, in general, survey telescopes do not have the required instrumentation and, even if they did, characterization observations would reduce the time spent surveying, and thus reduce the discovery rate. The same is true of follow-up astrometric observations; survey time and space-based instruments should not be spent on obtaining necessary astrometric data for objects that can be observed from the ground and accomplish the same goals.

Finding: Despite the limitations of ground-based telescopes for detection of NEOs, observation by ground-based systems is necessary for subsequent characterization of NEOs after discovery.

Recommendation: If NASA develops a space-based infrared near Earth object (NEO) survey telescope, it should also continue to fund both short- and long-term ground-based observations to refine the orbits and physical properties of NEOs to assess the risk they might pose to Earth, and to achieve the goals of the George E. Brown, Jr. Near-Earth Object Survey Act.

This chapter has identified the current state as well as some of the limitations of ground-based visual NEO surveys. Chapter 4 addresses space-based platforms for NEO surveys.

___________________

21 S. Chesley and P. Vereš, “LSST’s Projected NEO Discovery Performance,” briefing to committee, February 25, 2019.