Incorporating Climate Change and Climate Policy into Macroeconomic Modeling: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 2 Federal Macroeconomic Modeling Examples

2

Federal Macroeconomic Modeling Examples

This session aimed to gain insight into the macroeconomic models and inputs used at the decision-making level. In his talk, Robert Arnold, Congressional Budget Office (CBO), echoed Stock by stressing that models are tools. He reminded the participants that there are no good or bad models and no unified model of the economy to which policymakers can turn. He said that there are only models that are or are not useful for the task at hand.

TROIKA PROCESS

John Lindner, Office of Management and Budget (OMB), and Frances Moore, Council of Economic Advisers (CEA), jointly presented the Troika economic assumptions and long-term budget projections used in the President’s budget. Lindner outlined the inputs to the macroeconomic models used for forecasting gross domestic product (GDP) and other headline numbers, highlighting three key points. First, the models used in the Troika process are designed to answer specific questions and largely rely on empirical data rather than theoretical models. Second, they use the Macroeconomic Advisers U.S. (MAUS) model,2 which has budgeting advantages and provides projections for national income products and accounts. Third, Lindner said that although models are essential tools, they require judgment. Although MAUS is a framework to understand the economy, Lindner made the point that economists in the Troika process must impose the administration’s outlook—which is informed by the proposed policies within the President’s budget—into this framework.

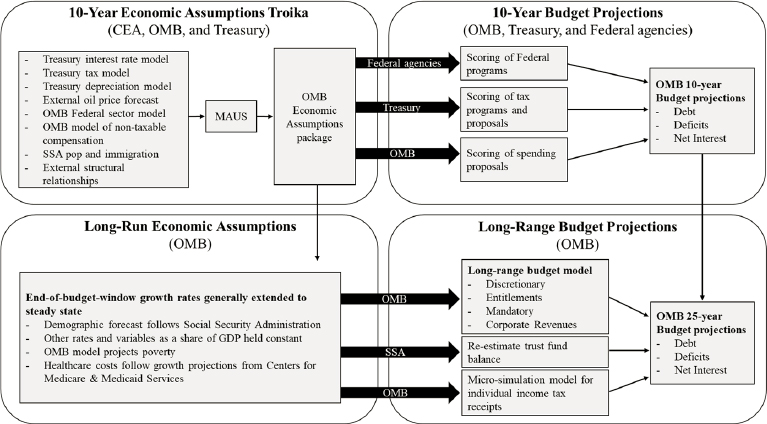

Figure 2-1 summarizes the framework used by CEA, OMB, and the Department of the Treasury. Lindner focused on the two left panels. The top left corner represents the framework for generating the economic assumptions in the 10-year budget projections. He noted that many important input variables (first gray box) come from external sources and are integrated into the MAUS framework. He said that this requires careful adjustments to ensure compatibility and accuracy without disrupting relationships between the important variables, including the national income accounts, needed for budgeting. After producing the economic assumptions, OMB uses them to produce a subset of variables for 10- and 25-year budget projections. After they make the 10-year budget projection, OMB extends it to produce an economic outlook over the following 15 years. Lindner said that after the initial 10-year projection, the economy is generally assumed to be on a balanced growth

___________________

2 Created by Macroeconomic Advisers, now owned by S&P Global.

path, although this may not work when incorporating climate risks. This may be due to their nonstationary and asymmetric nature which can change the economy’s structure and the historical relationships that underpin the Troika forecast.

In the bottom left box, OMB assumes that the U.S. economy is on a balanced growth path, keeping most growth rates, income variables, interest rates, and the unemployment rate constant over a 15-year window. In President Biden’s last two budgets, climate-influenced alternative scenarios were considered in which physical damages alter the long-run productivity path, producing a set of alternative debt-to-GDP paths.

Lastly, Lindner discussed how the MAUS model represents real-world processes. First, it imposes some structure to capture some of the historical economic relationships. Modified variables incorporate additional factors such as market data, policy proposals, and external forecasts. Notably, across the budget, the climate impacts on the macroeconomy are not explicitly considered beyond the alternatives in the long-run assumptions and projections or what is captured in historical relationships in the economic assumptions.

After Lindner outlined the macroeconomic forecast framework for the President’s budget, Moore explained OMB’s and CEA’s efforts to integrate aspects of climate risk into the long-term budget scenarios and potential next steps for full integration. In the fiscal year 2024 Climate Risk Alternatives, Moore described how CEA and OMB introduced central estimates of climate change’s physical risks into the Troika macroeconomic forecast. Moore said that the Interagency Technical Working Group (ITWG) led by CEA and OMB is limited in capacity and timing and relies on published estimates of macroeconomic effects—specifically, on U.S. or North American GDP effects.

SOURCES: Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) and Office of Management and Budget (OMB) (2023).

After combing the literature, CEA extracted damage functions from various published studies, including ones that used computable general equilibrium (CGE)–style models, bottom-up or enumerative sector-by-sector models, and top-down econometric studies. CEA combined the single, aggregated damage function with three global temperature scenarios, altered by the future global emissions pathways, resulting in different GDP trajectories. Moore reinforced that these trajectories are then used in fiscal planning measures passed on to the OMB budget model to determine the alternative fiscal trajectories under the different future GDP trajectories. In this way, climate risk alternatives were presented in the most recent President’s budget.

CEA and OMB (2023) also outlined a broader agenda for integrating the transition and physical risks of climate change into the macroeconomic forecasting framework. They considered two previously unused sources of information for this purpose: research on energy systems and climate policy and studies of climate damages and their impacts.

Moore said that because they are most concerned with connecting to the macroeconomic forecasting framework used by the Troika, CEA focuses on factors of production, primarily capital, labor, and productivity. She noted that energy is also a key consideration. Table 2-1 outlines the broad categories of critical macroeconomic variables that the ITWG considers and how the energy system or physical climate risks could affect those macroeconomic outcomes, though it is not exhaustive. CEA and OMB relied particularly on collaboration with the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and the Environmental Protection Agency’s National Center for Environmental Economics and the Climate Change Division on transition and physical climate risk quantification, respectively.

Moore then explained how climate may enter the Troika process. Starting with the 10-year economic assumptions, Troika uses the MAUS framework to understand the macroeconomic forecast. Climate change and climate policy could affect the macroeconomy through the energy system, key supply-side factors, and other relevant variables (gray box in Figure 2-2). CEA also considers how those variables may feed into the longer-term macroeconomic assumptions performed by OMB, which assumes a future balanced growth path. CEA has identified several variables that could potentially be linked to preexisting climate and energy system models. Moore proposed a framework to incorporate climate better using the MAUS framework (Figure 2-2). The framework could start with a comprehensive climate transition scenario, covering U.S. greenhouse gas emissions and global climate policy. Moore noted that considering physical climate risks also involves assessing actions taken by other countries. However, because of the simplified balanced growth path assumption, there are limitations to the number of variables that can be incorporated into the MAUS framework, particularly for the long-term economic assumptions.

Moore highlighted several challenges. First, the MAUS model’s reliance on historical relationships, particularly around energy production, creates difficulties when economists try to impose significant changes in the energy system. For example, the models may be parameterized around the assumption of the current importance of oil imports and exports for net investment; however, that importance is likely to change with the growing

adoption of electric vehicles. Moore said that it is difficult to represent these changes without a structural model of the energy system. Moreover, the model is limited to the United States, yet there are important international spillovers in energy, capital, clean energy, technology markets, etc.

TABLE 2-1 Linkages Between Macroeconomic Variables and Climate Risks

| Macroeconomic Variable | Transition Risks | Ability to Quantify | Physical Risks | Ability to Quantify |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capital | Increased investment in clean technologies | Good | Destruction from storm damage, resources required for adaptive investments | Moderate |

| Lower investment or premature retirement of fossil fuel infrastructure | Good | Added uncertainty, risk premia, and insurance availability | Limited | |

| Labor | Potential skill and geographic mismatch from shifting energy (and connected) industries | Limited | Labor supply | Moderate |

| Population (mortality and migration) | Moderate | |||

| Energy | Effects on energy price levels and volatility from global climate policies | – | – | – |

| Productivity | Improved energy productivity from new technologies | Good | Land | Good |

| Labor | Good | |||

| Capital | Moderate |

NOTE: This is not a comprehensive list of possible pathways.

SOURCES: Adapted from John Lindner and Frances Moore workshop presentation, June 14, 2023.

Another challenge that Moore identified is the missing quantification of climate damages, especially in the short-term, 10-year framework where economic equilibrium is uncertain. Although tools exist for short-term responses and shifts in equilibria, this might lead to different sets of models. Lastly, Moore noted that addressing or representing risks and uncertainty is difficult when producing a single set of economic assumptions that goes to agencies for budgeting.

SOURCES: Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) and Office of Management and Budget (OMB) (2023).

CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET OFFICE

Arnold discussed CBO’s role in creating an economic baseline and forecasting models, emphasizing their nonpartisan support for Congress and that they make no recommendations about policy. CBO’s Macroeconomic Projections Unit has two main tasks: (1) providing economic information to Congress and, more importantly, (2) producing an economic forecast that is used as an input to budget projections. CBO usually produces a forecast twice yearly, aside from producing a rapid sequence of forecasts since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. In a standard year, CBO produces a forecast in January, an update in August, a long-term or 30-year budget outlook, and a Social Security analysis during the summer, typically extending 75 years.

CBO operates with different divisions, like the Troika process. The Macroeconomic Projections Unit provides economic data used by the budget and tax divisions, which produce budget and tax revenue projections, respectively. CBO produces around 50 variables—including GDP, interest rates, and incomes—which are provided to the budget, tax, and other divisions. Arnold noted that CBO’s emphasis on incomes, especially in their forecasts under current law, sets them apart from the private sector, as they assume current laws persist throughout the forecast horizon, leading to potential forecast differences with private-sector forecasters.

SOURCE: Presented by Robert Arnold on June 14, 2023.

Arnold provided an overview of the models that CBO uses (Figure 2-3), which is like the Troika process. Arnold noted that the most important aspect of their models is that they enforce the variables to add up to, for example, the National Income and Product Accounts. Their central macroeconometric model combines behavioral equations and identities, with identities being equations that are true regardless of the values of the right-hand-side variables. For example, GDP is an identity, where GDP is always going to equal the sum of consumption, private investment, government consumption and investment spending, and net exports, regardless of whether consumption, for example, is high or low. Identities are vital for CBO to maintain internal consistency.

CBO’s model also includes many behavioral equations. For example, consumer spending is a behavioral equation based on factors such as disposable income and wealth. These relationships are mathematically expressed using a stochastic equation. Like OMB, CBO has numerous inputs to their model, called exogenous variables, shown on the far left of Figure 2-3. These receive limited feedback from other economic outcomes, such as population, energy prices, and foreign growth. They also consider external policy variables. CBO’s forecasting model also represents labor force participation and long-term growth outcomes.

CBO follows an iterative process of inputting data into their model, generating outputs, and reviewing them internally and externally. Arnold noted that the key element of CBO’s model is the interaction of aggregate demand (how much entities want to spend) and aggregate supply (what businesses want to provide) at a given set of prices. CBO models both sides, determining outcomes for other model variables. For example, potential output is determined by the growth model, which uses supply-side factors such as labor supply, capital stock, and labor and capital productivity.

Arnold explained that the model distinguishes between the short term (~2–5 years), where business cycle fluctuations matter because aggregate demand drives most economic

outcomes, and the medium and long term, where supply-side factors play a larger role. In the medium and long term, all real GDP movements are assumed to be determined by potential GDP changes. Lastly, the budget projections, on the right of Figure 2-3, are CBO’s outputs but also serve as inputs in subsequent iterations for their model.

After outlining the forecasting model, Arnold highlighted a couple of paths for climate to enter the framework in the short term:

- Analysis of fiscal policy: Traditional analyses of fiscal policy, such as the Inflation Reduction Act (see Chapter 5), can impact economic activity in the short term by reallocating government spending and resources, potentially displacing more-productive activities.

- Infrastructure: CBO assesses the rate of return on infrastructure investment, which not only has direct spending effects, but also affects productivity due to infrastructure changes.

- Risk on the cost of capital and productivity: CBO’s models rely on historical data, and so contemporary changes to historical relationships, such as those related to climate, are not directly incorporated into their models.

Arnold acknowledged that while the CBO model’s projections include minor impacts of climate change, the model is not well suited to estimate the overall economic effects of climate change, since it consumes rather than produces climate effects on the economy. He argued that their model is better suited for incorporating external estimates of climate effects on the macroeconomy and tracking their implications for budget and economic variables. For example, CBO’s Micro Studies Division estimated that real GDP will be ~1 percent lower in 2050 compared to a scenario without worsening climate conditions. This estimate is integrated into the Macroeconomic Division’s forecast by adding it to their estimate of total factor productivity, influencing real GDP and various model variables, including tax revenues.

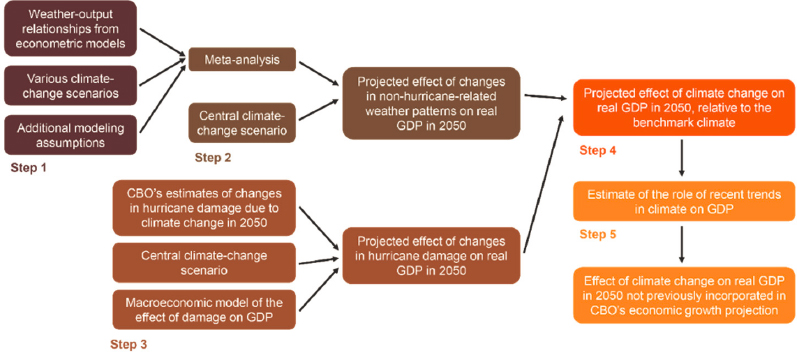

Although Arnold acknowledged that he is not well versed in their model, he gave a brief overview of the Micro Studies Division’s method (outlined in Figure 2-4), which consists of two parts. First, they estimate the GDP effects of temperature and precipitation changes, derived from external research and consolidated into a single estimate. Second, they estimate the impact on GDP due to hurricane damage, which was initially separate but was integrated into a macroeconomic model to quantify its effect on GDP.

DISCUSSION

In the subsequent discussion, Galina Hale, University of California, Santa Cruz, brought up the emergence of new industries in response to climate change, such as alternative energy and direct carbon capture. She questioned whether these could potentially boost GDP growth and if federal macroeconomic models could incorporate those effects. Moore noted that CEA, with OMB and the ITWG, is assessing the combined effect of shifting investments, such as the investment in new technologies and the divestment from

polluting industries and the aggregate effects of that. She said that their model has captured the first-order effects of those shifting investments, but imperfectly captures second-order effects of newer industries with network or tipping dynamics within the Troika process.

SOURCE: Presented by Robert Arnold on June 14, 2023.

Arnold added that structural change is a constant aspect of the macroeconomy because the economy is constantly adapting. Although CBO’s models are not designed to capture energy shifts, they do account for some structural changes. Moreover, Moore noted that energy plays an important role in the macroeconomy, impacting factors such as inflation and inflation expectations. Therefore, the economic relationships with energy are embedded into aspects of the macroeconomic forecast. Moore emphasized the importance of examining how the energy transition specifically affects the macroeconomy, distinct from more general structural transformations.

Lori Hunter, University of Colorado, Boulder, asked Evan Herrnstadt, CBO, about the weather–output relationships in econometric models and if there are any concerns or gaps. Herrnstadt mentioned that these models study aggregate output in relation to temperature and precipitation shocks, but do not examine individual mechanisms. He acknowledged that uncertainties and missing elements are discussed in Herrnstadt and Dinan (2020). Additionally, he mentioned that the models are U.S.-specific and do not account for global factors, such as trade spillovers and migration, suggesting potential areas for academic research.

James Rising, University of Delaware, noted that both OMB and CBO constrain inputs but emphasized the need for targeted models to understand the variables endogenous to physical climate and transition risks, their economic costs, and their relationship to the

overall economic system. He inquired about the opportunities to endogenize externalities, shifting from constraining inputs to integrating them into the core models.

Moore agreed that endogeneity is a concern and mentioned that CEA has a chain of modeling that connects one model to another. For example, the Global Change Analysis Model takes energy demand as a given, but if energy prices are changing, energy demand is not exogenous and potentially quite important. Although Moore appreciated the value of a whole-economy modeling approach, she recognized that equilibrium frameworks may miss dynamics. Lindner emphasized that models serve a specific purpose and can have limitations in endogenizing other macroeconomic impacts.

Chris Varvares, co-head of US Economics at S&P Global Market Intelligence, raised two key points. First, he added that a big source of uncertainty is the energy efficiency parameter, which relates output to energy inputs. This parameter depends on energy prices and is technology dependent, making it hard to forecast. He suggested explicitly addressing this parameter as a separate assumption calibrated in the production functions that will be used in the future. Second, he brought up the availability of critical minerals, advocating for its inclusion in the list of climate uncertainties affecting macroeconomic factors. Varvares emphasized that while economists typically consider supply and demand in equilibrium, the physical limit of commodity supplies should be considered. Moore agreed, noting the difficulty of capturing global supply constraints in a U.S.-focused modeling framework. Arnold added that Congress typically wants a single number or a path of numbers in budget projections, but scenarios may be useful for visualizing different outcomes.

Robert Kopp, Rutgers University, asked the panelists how their models consider shocks. Arnold said that shocks are not forecastable, so they try to get the risk in as well as possible. For example, CBO includes the possibility of a recession in their projections. Moore added that the Troika process could consider physical risk in the 10-year time frame but echoed Arnold’s remark that shocks are not forecastable. At the macroeconomic level, an extreme event has to be major for it to show up in aggregate GDP, such as Hurricane Katrina resulting in measurable aggregate energy system impacts. As such, Moore suggested focusing on identifying the pathways from shocks that aggregate into larger macro effects.