Incorporating Climate Change and Climate Policy into Macroeconomic Modeling: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 6 Public and Financial Sector Climate Risks and Response and their Macroeconomic Implications

6

Public and Financial Sector Climate Risks and Response and their Macroeconomic Implications

This session examined how many aspects of the economy are already being affected by the climate crisis, across sectoral, spatial, and temporal scales. In particular, physical climate risks are largely felt at the local or regional scale and currently may appear as individual sectoral risks. However, Rachel Cleetus, noted how these risks may aggregate to affect the macroeconomy and how the community can learn from research to shift policies and actions from a reactive disaster response to a proactive recognition of the risks. This could aid in planning toward climate resilience that could impact the livelihoods and critical infrastructure of so many people and parts of our country. This session explored these themes by focusing on recent work studying trends and behavioral patterns in the insurance and housing markets and the local government response to climate change.

INSURANCE MARKETS AND BELIEF HETEROGENEITY

Laura Bakkensen, University of Arizona, discussed her research on analyzing natural disasters using econometric techniques. She highlighted the importance of bridging the micro- and macroeconomic gap, potentially leading to richer results to incorporate into macroeconomic modeling. Bakkensen and her co-author, Lint Barrage, ETH Zurich, attempted to bridge this gap by translating local and sectoral climate risks into their macroeconomic impacts.

Rather than focusing on the impact of natural disasters on economic growth, Bakkensen and Barrage used empirical estimates of the impacts of cyclones on the structural determinants of growth (Bakkensen and Barrage, conditionally accepted). This method allowed them to use extensive data and integrate their findings into a stochastic endogenous growth cyclone–climate–economy model. Additionally, they found that using a structural approach aided in informing empirical specification and interpretation. For example, they showed that modeling decisions, such as operationalizing a climate risk, can lead to diverging results in empirical studies. However, Bakkensen and Barrage found that the difference in findings may not be in conflict but rather represent different parts of the overall equation. The structural approach also enables a more direct integration of empirical findings into the macroeconomic literature and for the findings and models to be more connected to the real world.

Next, Bakkensen highlighted her work on climate risk in the collateralized debt market. Specifically, she and her collaborators built a novel extension of an economic model

to account for belief heterogeneity regarding climate change (Bakkensen et al., 2023). Contrary to previous findings (e.g., Geanakoplos, 2010), Bakkensen’s team found that, when considering long time horizons and belief heterogeneity, optimistic individuals, while more likely to pay high prices for risky assets, were less likely to use leverage.

Instead, Bakkensen and coauthors’ recent research using extensive home sales and sea level rise data along the eastern U.S. seaboard over a decade shows that pessimistic individuals are more likely to use leverage and opt for longer-term debt contracts. Bakkensen suggested that this might be because mortgage default can serve as a form of implicit insurance, potentially addressing gaps in climate risk coverage in insurance markets. For example, flood risk in the United States is predominantly covered by the National Flood Insurance Program. However, Bakkensen noted that the coverage has limits, typically up to $250,000 per property and are often short-term policies, which may not adequately address long-term climate risks.

Moreover, Bakkensen emphasized that having better climate information and awareness may not automatically resolve the concentration of climate risk in financial markets. In fact, she suggested that the increased attention to climate risk could lead to more people getting mortgages. She stressed the critical role of policy and government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs), building on previous work such as Ouazad and Kahn (2019). She noted that current policy constraints mean that climate risks are not factored into pricing securitized mortgage portfolios. As a result, banks might still be willing to issue riskier loans, knowing they can securitize and transfer them to GSEs. Empirically, Bakkensen’s research suggested that this pessimistic channel, where individuals who are cautious about climate risks take on more debt, is primarily in the conforming loan segment that can be securitized to GSEs.

As such, Bakkensen stressed the need to examine the interaction between public policy and collateralized debt markets, the influence of belief heterogeneity, and the role of climate information in addressing climate-related risks in financial markets. She suggested that insights in this realm are critical in developing effective strategies to mitigate the impact of climate change on the financial sector.

Lastly, Bakkensen discussed her research on insurance and climate risks, particularly flood insurance. She noted that flood insurance is primarily a public insurance product in the United States, but private markets are actively involved in insuring against other climate risks. In a joint paper with Lala Ma (Bakkensen and Ma, 2020), they examined how individuals sort themselves by flood risk, specifically within metropolitan areas in South Florida. Similar to common assumptions, they found that wealthy White populations tend to live in higher coastal flood risk areas in South Florida. However, for inland flood risks in the same region, low-income Black and Hispanic residents are more likely to move to flood-prone areas, often due to lower property prices. Bakkensen and Ma (2020) employed a structural sorting model to assess the counterfactual price performance of the National Flood Insurance Program. They found that certain groups, particularly low-income Black and Hispanic residents, might not move away from high-risk areas when insurance prices increase, leading to potential unequal burdens of cost from these price reforms. Bakkensen

thus highlighted the importance of considering unintended consequences and potential disproportionate impacts on vulnerable groups when implementing policy changes.

In closing, Bakkensen emphasized the need to address gaps in insurance markets, the role of state-run flood insurance markets, and public insurance interventions to cover climate risk–prone areas where private insurers may be hesitant to provide coverage.

PHYSICAL CLIMATE RISK AND HOME BUILDING AND BUYING TRENDS

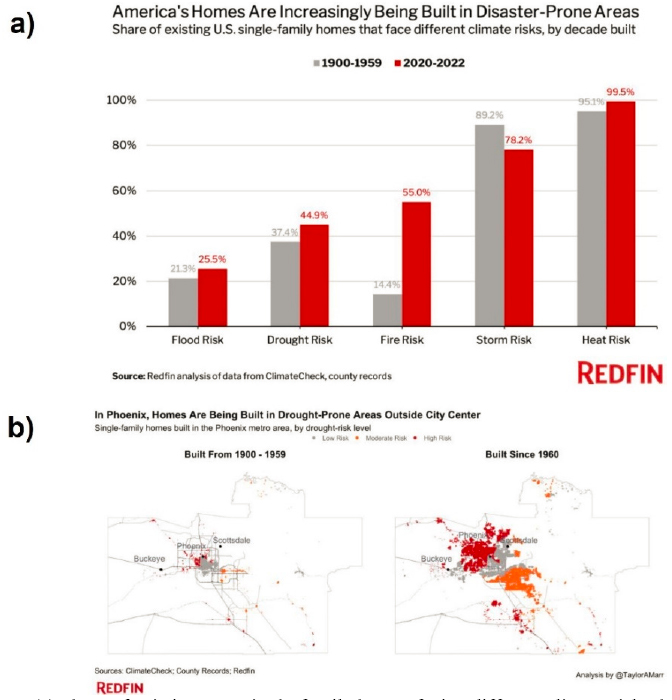

Daryl Fairweather, Redfin, discussed her research on climate risks and their impacts on the housing market. She mentioned that Redfin incorporated climate data into their platform in late 2020, providing data on various climate risks at the individual home level. Fairweather said that their research revealed a trend in homes being built in riskier areas, especially for fire risk. In the first half of the 20th century, only 14 percent of homes were built in fire risk areas, which has risen to 55 percent (Figure 6-1a). Fairweather noted that building patterns can exacerbate climate change because of the encroachment into climate-risk areas. For example, in Phoenix, Arizona, housing development in high drought-risk areas has strained water resources, leading to limits on further construction (Figure 6-1b).

Moreover, Fairweather pointed out that people are not only building homes in risky areas, but are also moving to them. Their data show a trend of people leaving less risky places (e.g., Midwest, Northeast) and moving to places with some of the highest climate risks (e.g., Florida, inland California). Fairweather also discussed an experiment Redfin conducted when they first introduced climate change data on their website. In a 3-month experiment, they showed flood risk data to half of their customers, while the other half were not shown the data.

Fairweather and her team found that Redfin users who viewed homes with severe flood risk were more cautious in their bids, choosing homes with significantly lower flood risk. Additionally, users in flood-prone areas such as Florida, Texas, and Louisiana were more likely to use the flood risk data. Fairweather emphasized the value of owning a home with lower flood risk, predicting that over time, homes in high-risk areas would appreciate less than those in low-risk areas. Moreover, she said that the trend of choosing lower-risk homes among the user group shown the risk data amplified over time. By the end of the experiment, there was a 25 percent decrease in searches for homes in high-risk areas.

Additionally, Fairweather discussed Redfin analysis of homeowner survey data, revealing that 58 percent of users have spent money to protect their homes from climate risks. About a third said they have invested $5,000 or more in resilience improvements, such as roof upgrades and landscaping. Although flooding and hurricanes are significant concerns, Fairweather said that extreme temperatures were the most common climate risk homeowners protected against, often using air conditioning or insulation. She also noted that roughly 36 percent of homeowners have flood insurance, which is the highest share among climate risks, underscoring the urgency of climate resilience for many homeowners.

SOURCE: Redfin analysis of data from ClimateCheck, county records.

Fairweather also discussed the policy implications of climate change and its impacts on different communities. Wealthier people and corporations have more resources to protect themselves and their investments, and governments are incentivized to protect more valuable assets. Historically discriminatory policies, such as mortgage redlining, can have lasting impacts on communities today.8 For example, Fairweather pointed out that historically redlined neighborhoods, which primarily targeted areas where Black and Brown individuals bought homes,9 often exhibit higher flood risk. These areas are still inhabited by

___________________

8 For more information on mortgage redlining, please see https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/redlining.

9 For more information on how redlining specifically targeted Black communities, please see https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/17/realestate/what-is-redlining.html.

predominantly Black and Brown communities. She raised the question of who bears the cost of climate change and who is allowed to stay or is forced to move, leading to considerations about government investment and relocation policies.

One potential path forward that Fairweather suggested is limiting building in high-risk areas, encouraging denser housing by eliminating single-family zoning in low-risk areas, and raising climate risk awareness. She emphasized the importance of providing climate risk information to homebuyers, as the Redfin experiment showed that people do not respond to general climate risk information. She explained that the key is to deliver and explain risk data effectively during the home-buying decision process to have a significant effect.

STRESS PATHWAYS ON LOCAL GOVERNANCE FINANCIAL RESPONSE TO CLIMATE CHANGE

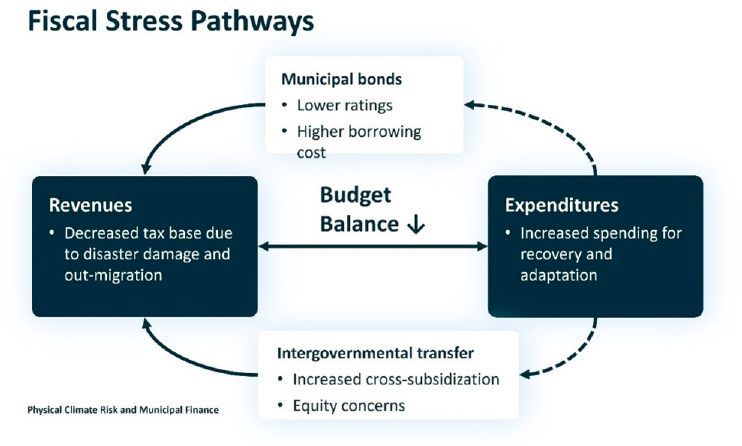

Penny Liao, Resources for the Future, highlighted the significance of considering local government finance in relation to the macroeconomic consequences of physical climate risks. She pointed out that local governments play a vital role in responding to and adapting to climate and disaster risks, and their capacity is essential. Liao also outlined multiple fiscal stress pathways by which physical climate risks stress local governments (Figure 6-2).

SOURCE: Presented by Yanjun (Penny) Liao on June 15, 2023.

After a local disaster, local governments face budget challenges for two main reasons: (1) increased expenditure on recovery and adaptation and (2) reduced revenues. Liao used California as an example, where her research showed that after a major wildfire event, a community’s spending increased by 40 percent for recovery, adaptation, public safety, transportation, and disaster preparedness. On the revenue side, disaster damage initially decreased the community tax base, and population migration can lead to long-term erosion of the property and sales tax base.

Liao explained that to address budgetary gaps and/or fund major adaptation projects, local governments have two additional funding mechanisms. The first involves municipal bonds, which offer cost-effective borrowing for short-term deficits. However, Liao said that research shows disasters often lower municipal bond ratings for affected communities, leading to increased borrowing costs and liquidity challenges. The second mechanism is intergovernmental transfers, such as federal disaster resistance and aid programs. Although these can aid recovery, Liao said that they also shift the perception of affected communities from low risk to high risk, potentially raising equity concerns.

Liao’s fiscal stress pathways (Figure 6-2) illustrate how communities’ budgets change after disasters. However, there is significant variation among communities. High-income counties tend to increase spending substantially, while low-income counties struggle to do so, often reallocating funds from other services. High-income counties can raise funds more easily and their tax revenue increases with intergovernmental transfers, resulting in moderate debt decreases. In contrast, low-income counties face challenges absorbing disaster damage due to fewer financial resources and limited ability to raise funds, leading to more debt. Underlying institutional factors may be the root of the difference in intergovernmental transfers received across communities. Recent research suggests that wealthier communities receive more disaster aid, potentially worsening the divide between high- and low-income areas, leading to varying economic trajectories. These results highlight the potential for equity concerns and implications for the spatial distribution of the population and production.

In her final remarks, Liao highlighted two potential surprises in the fiscal challenges faced by local governments following disasters. First, properties at risk may be overvalued due to various factors such as disclosure laws, lack of information, socialization of disaster clause, and subsidized flood insurance. Liao and collaborators recently showed that correcting this overvaluation could lead to acute revenue decreases in counties reliant on property tax revenues (Figure 6-3), necessitating alternative funding sources for community services. Second, insurance availability and affordability issues are increasing, posing challenges for homeowners who rely on insurance to fund disaster recovery. Because of ample coverage, California’s property tax revenues have not been impacted significantly by increasing wildfire activity, but this is changing. Liao’s analysis revealed that high-wildfire-risk areas in California will experience up to 20–30 percent increase in insurance rates, which will also likely increase with time (Figure 6-4). Most recently, two major private-sector insurance companies announced they will not offer any new policies in California owing to rising wildfire risk. Similar trends in rising insurance rates have been observed in other states facing increasing physical climate risks, such as Florida, Louisiana, and Texas.

This may result in a widening disaster insurance coverage gap, leaving more homeowners underinsured for rebuilding after disasters, further straining local governments’ finances.

SOURCE: Gourevitch et al. (2023).

SOURCE: Gourevitch et al. (2023).

DISCUSSION

During the discussion, Cleetus asked how the range of risk trends discussed in the workshop—spanning individual homes, property tax base, mortgage market, retirement portfolios, government budgets, insurance, etc.—might impact the macroeconomy. Fairweather highlighted the significant role of housing in the economy. She mentioned that the mismanagement of the housing market, especially in places such as California where insurance companies are withdrawing due to rising risks, could lead to increased costs for homeowners that will have large impacts on household spending. Moreover, she said that properly pricing in risk may result in acute fiscal stress in vulnerable communities. Liao highlighted that many risks related to climate change are not priced into economic models. She proposed that future work will need to explore when and how the risk will be priced in and what these implications mean for the macroeconomy.

Bakkensen emphasized the need to carefully observe and quantify risks and their interactions to integrate them into macroeconomic models. She said this will involve understanding how risks affect decisions on aspects such as where to live, invest, and save for both firms and individuals. Quantifying these trends using climate stress testing can provide insights into what to expect in financial areas. Bakkensen highlighted the importance of considering long-run climate risk, including both the longer-term dynamics and individual climate events, and examining tail events to understand potential shocks across sectors, firms, and homes.

A workshop participant asked Liao about assessing overvaluation in the context of homebuying under speculation of various factors, such as government interventions, bailouts, and subsidies. Liao explained that her current model quantifies overvaluation when comparing expected damage versus discounts on the values of properties at risk, which does not account for expectations about government aid. In general, she mentioned that people are overly optimistic about government aid. In the future, Liao noted that this gap between expectations and reality, combined with policy uncertainty, will result in price uncertainties accumulating over time and appearing in the valuation discrepancies.

Another workshop participant asked if there are opportunities to address potential overvaluation or mispricing of assets by providing more risk information. Liao suggested that the way information is presented is important, as people tend to struggle to process information about rare but high-impact events. She proposed presenting risk information in financial terms, such as economic and insurance costs and trends in current and future values, as it might make it more understandable for individuals.

Fairweather emphasized that the timing and audience of the risk information can have large impacts. She noted that currently, large real estate corporations are the most interested customers in climate data. However, this information is also important for individuals buying homes, municipalities, state governments, real estate investors, and urban planners when making decisions about construction and zoning. Furthermore, Fairweather remarked that people tend to forget about risks and disasters over time, so providing information during the decision-making stage serves as a helpful reminder of potential risks.

Bakkensen remarked that disaster events have more digestible information available and can be transformed into great learning tools over time. She cited examples from Vietnam where households adapt their finances, saving more and changing investments, following tropical cyclones. Bakkensen suggested that access to risk information may influence household decisions, which can potentially have macroeconomic implications.

The panelists also discussed the tension between individual homeowner decisions and the need for public policy regarding flood risk and managed retreat. Fairweather remarked that resolving this tension may require federal coordination, as incentives vary across communities. She highlighted the “political economy prisoner dilemma” that can arise due to these differences and proposed federal-level incentives or prescriptions to address these challenges. Fairweather also noted that local policies can have a large impact through spillover benefits that can reduce overall risk and improve resilience in the community. She cited the example of the Coastal Barrier Resources Act as a successful measure to curb development in risky coastal areas. Fairweather emphasized that proactive local land use choice can be effective in reducing risk in communities.

Robert Kopp asked the speakers if the locally significant impacts discussed in the session could propagate up to national macroeconomic significance. Fairweather mentioned migration, as people leaving high-risk areas can affect neighboring communities and the entire country. Liao suggested systematic devaluation of properties in high-risk areas due to large-scale insurer withdrawals. Bakkensen pointed to the mortgage and property markets as a potential channel for further study, noting how unanticipated (nonclimate) risks in these segments historically had global repercussions during the Great Recession.

Cleetus highlighted the significance of understanding risk. She emphasized the need to quantify these risks and understand how they can interconnect and amplify, spanning various sectors and encompassing climate, economic, and policy factors. She emphasized that what might seem like small local risks can, in fact, have substantial implications, underscoring the importance of making informed economic decisions.