Incorporating Climate Change and Climate Policy into Macroeconomic Modeling: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

Macroeconomic models play a crucial role in decision making and federal budget planning but may not fully account for the economic disruptions caused by extreme climate-related impacts (e.g., extreme heat, storms, and wildfires) as well as slow-onset events (e.g., sea level rise). However, accurately quantifying and predicting these impacts is challenging due to the complexity of climate dynamics and the variations in impacts across different scales.

Although economists have advanced in developing data, analyses, and tools to understand climate-related impacts on the macroeconomy broadly, scientific understanding of climate change dynamics has outpaced economic understanding of climate change and climate-related impacts and their incorporation and representation in macroeconomic models and analyses. Additionally, research on the potential effects of climate change and climate-related policies on forward-looking macroeconomic indicators (e.g., economic growth, inflation, employment, income and wealth distribution, interest rates, tax revenue, government expenditures, and trade balances) and the effects of economic systems on the environment and climate is lagging.

Efforts to incorporate climate and climate-related factors into macroeconomic analyses often grapple with complexities related to macroeconomics, climate science and impacts, multiple policy instruments, and their intersection and interactions. This workshop explored the current macroeconomic models and approaches to representing and incorporating climate and climate-related impacts in macroeconomic models and analyses. It attempted to outline the landscape in which this work is embedded to summarize the gaps and limitations, data analyses that may be useful, and potential areas for improvement in existing approaches.

WORKSHOP DESCRIPTION

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine convened a workshop on June 14–15, 2023, in Washington, D.C., and virtually online to consider current macroeconomic models and suggest opportunities that may improve the incorporation of climate-related factors into macroeconomic modeling. The workshop was the first orga-

nized under the Roundtable on Macroeconomics and Climate-Related Risks and Opportunities and planned by a committee of Roundtable members.1 See Appendix A for the statement of task and Appendix B for committee biographies.

The workshop covered the extent to which current federal macroeconomic models consider climate change, methods employed by the research community to forecast risks associated with the impacts of climate change (physical risks) and the transition to a low-carbon economy (transition risks), and public and financial sector risk management responses to physical climate risks. The workshop featured breakout discussions broadly themed around the workshop sessions for workshop participants to suggest opportunities to advance the field of macroeconomics and its connection to climate science. The 2-day discussions culminated in a synthesis discussion of potential pathways for integrating these modeling communities. See Appendix C for the workshop agenda. Dozens of scholars, policymakers, and civic and business leaders working at the intersection of climate, macroeconomics, and public policy attended.

BACKGROUND AND MOTIVATION FOR WORKSHOP

James Stock, Harvard University, noted that models are tools to address real-world problems rather than an end in themselves. In his opening keynote, he provided an overview of macroeconomic approaches, applications, and model inputs and outputs. See Box 1-1 for a clarification on the distinctions between the terms he used in his presentation. Because the Roundtable’s charge is narrower than the workshop’s, Stock oriented his presentation around U.S. government function at the macroeconomic level. He discussed how climate-related uncertainty may affect macroeconomic models and their implications, mapping the workshop’s climate and macroeconomic landscape into four corners: long- or short-term and physical or transition risks.

Macroeconomic Modeling Approaches

Stock outlined three different categories of economic work and how climate factors into them.

- Traditional economic work: This includes understanding the effects of monetary and fiscal policy on the economy and projecting gross domestic product (GDP) growth, employment, and tax receipts. Stock said climate can play a role in various ways depending on the time frame and the policy-relevant question.

- Analysis of specific climate policies: Stock remarked that climate policies have budgetary implications, and macroeconomists need to estimate these impacts.

___________________

1 This proceedings has been prepared by the workshop rapporteurs as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. The planning committee’s role was limited to planning and convening the workshop. The views contained in the proceedings are those of individual workshop participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all workshop participants, the planning committee, or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

- Long-term calculations: Stock explained that these are calculations with long-term horizons (i.e., centuries) to quantify the impacts and damages of emission paths, growth, and so on, such as the social cost of carbon (SCC). Although not a primary focus of the Roundtable, they are briefly mentioned and discussed in Chapter 4. For further reference, Stock mentioned a National Academies’ study on SCC (NASEM, 2017).

See Chapter 6 for an example using the Inflation Reduction Act. He mentioned that the ability to jointly understand the budget and climate impacts of policies helps assess their macroeconomic significance.

BOX 1-1

Stock’s Key Definition Distinctions

In his presentation, Stock used “climate problems,” “climate change,” or “climate challenges” interchangeably. Although transition risk is often understood as risk framed around policy, he used “transition risk” to encompass all the issues associated with moving toward a net-zero carbon future, including the challenges that arise (e.g., challenges for businesses, adaptation, mitigation). He used “transition risk” to encompass the risks to human systems. Stock used “risk” as uncertain future events with impacts and associated distributions. Those uncertain future events often have distributions associated with them, which are nonstationary.

SOURCE: Presented by James Stock on June 14, 2023.

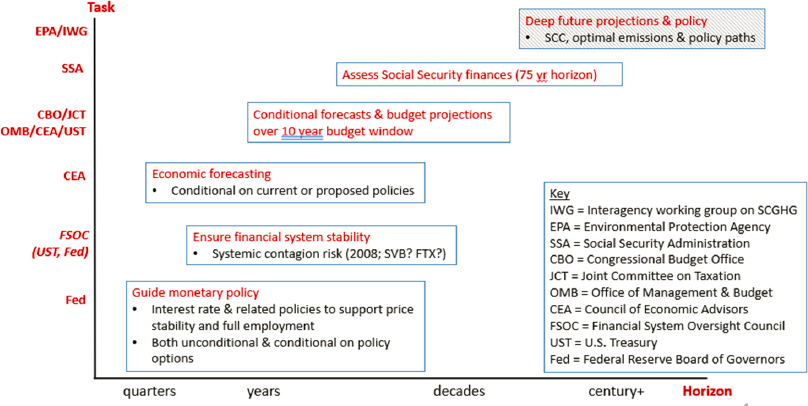

Stock showed a diagram of different tasks that macroeconomists tackle at the federal level (Figure 1-1), which may also inform or elucidate global perspectives and work. The diagram uses time (x axis) and different federal actors (y axis).

- Guiding monetary policy: Stock said that the Federal Reserve Board of Governors (the Fed) plays a vital role in setting the interest rate and related policies to support price stability and full employment. It is both unconditional and conditional on policy options.

- Ensuring financial stability: The Financial System Oversight Council, including the U.S. Treasury and the Fed, is charged with understanding systemic risks to the financial system, working on multiple horizons.

- Forecasting economic conditions: The Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) conducts economic forecasting with the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the U.S. Treasury (i.e., the Troika), considering future economic conditions or potential impacts of specific policy implementation.

- Conducting conditional forecasts and 10-year budget projections: The Congressional Budget Office (CBO), Joint Committee on Taxation, and OMB, CEA, and U.S. Treasury conduct 10-year budget projections, in both Congress and the executive branch. Chapter 2 outlines some of the federal macroeconomic models used for this work.

- Assessing Social Security finances: These budget calculations work at the 75-year horizon.

- Making deep future projections: These are the deep-horizon calculations, such as the SCC calculation.

Stock noted that understanding the key inputs and outputs of various macroeconomic models can help identify where climate factors may affect these models. Please refer to the Glossary for definitions. Key inputs include

- Long-run growth: Determinants of long-run growth include growth rates of total factor productivity, labor productivity, capital stock, labor force, and the long-term or natural rate of interest (R*).

- Current economic conditions: These conditions are essential for shorter-term policy, such as monetary policy, economic forecasting, and budget projections. These factors include overall economic activity, GDP growth, employment, and other important factors that affect macroeconomics, with no climate impacts in these inputs.

These models generate outcomes related to future economic activity, which may be macroeconomic models’ primary outcome or a component.

- Future economic activity: Stock noted that future economic activity includes all the current variables describing the economy (e.g., employment, employment growth, GDP growth, inflation, sectoral inflation, and interest rates).

- Budget-specific information: Tax receipts, expenditures, and various economic statistics come from the models.

- Welfare: See Box 1-2.

BOX 1-2

GDP Versus Welfare

Stock distinguished gross domestic product (GDP) from welfare, defining GDP as the market value of domestic goods and services and welfare as the value gained by a person obtaining goods and services. When considering climate change and its economic effects, there can be different benefits and trade-offs when using GDP or welfare. Stock stated that climate-induced mortality will affect welfare but may not affect GDP unless the individual affected contributes to the economy, such as being of working age. Although GDP measures market value, it does not necessarily capture overall value. Stock highlighted that many damages that are important to people, such as climate-induced mortality and species loss, will affect welfare but not GDP. This difference in market value and value underscores the importance of tailoring economic modeling to user needs when determining which measurement to incorporate.

NOTE: Timing and magnitude are illustrative.

SOURCE: Presented by James Stock on June 14, 2023.

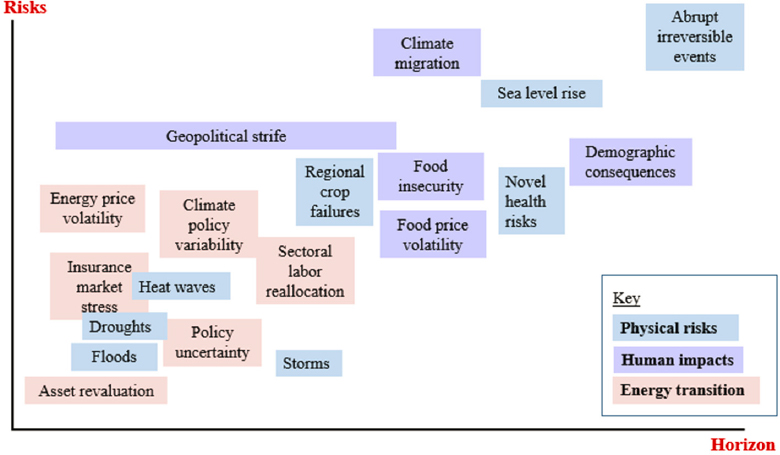

Climate Risks

Climate risks vary in their timing and magnitude. Stock provided a conceptual framework by mapping the macroeconomic-climate landscape into four corners: long- or short-term and physical or transition risks, each with arbitrarily different levels of magnitudes (Figure 1-2). The goal of this framework was to give an idea of how one might think about risks. In the upper right-hand corner, Stock explained that abrupt, irreversible events (e.g., West Antarctic Ice Sheet loss) could potentially be highly damaging but are distant in the context of macroeconomic horizons. In the lower left-hand corner, Stock noted that there have been substantial asset revaluations (e.g., coal company revaluation), and that aspect of the energy transition has already been incorporated into asset markets; however, many of these revaluations have limited macroeconomic consequences. Higher on the graph, other risks are relatively straightforward (e.g., droughts, agricultural productivity) and easier to consider how they impact the macroeconomy compared to others, such as geopolitical strife, and therefore more easily incorporated into macroeconomic models.

TABLE 1-1 Timeline of Physical and Transition Risks

| Economic variable | Long Run π*, R*, u*, μ | Short Run π, u, Shocks, Business Cycles |

|---|---|---|

| Physical |

|

|

| Transition (human systems) |

|

|

SOURCE: Adapted from James Stock workshop presentation, June 14, 2023.

Similarly, Stock provided a table categorizing some physical and transition risks at different horizons (Table 1-1). The long-run economic variables that macroeconomists consider include the steady-state rates of inflation (π*), interest (R*), and unemployment (u*), as well as the growth rate of productivity, among others. These may be affected by a wide range of physical and transition risks, such as sea level rise, adaptation cost, and risks associated with significant climate changes over time.

The short-term economic variables that macroeconomists consider are inflation (π), unemployment (u), business cycles, etc. Stock emphasized that many current physical risks have not made significant macroeconomic impacts yet and that shorter-term macroeconomic risks are often associated with transition or human-system risks. Some examples in the lower right corner of his figure include energy price shocks, asset price shocks, policy transition shocks, and political and geopolitical risks. He also noted that “unknown unknowns” are something macroeconomists should always consider.

Stock emphasized that there are different macroeconomic models tailored to different horizons. Each model has a different purpose, each purpose has a different model, and there are different macroeconomic modeling approaches. Each model has unique assumptions and simplifications to address specific problems. Stock said that, as such, there is no single comprehensive economic model. Climate enters these models in different ways, such as through the GDP growth baselines, which have implications for decision making, particularly in 10-year budget projections calculated by agencies such as CBO or OMB. These projections include both productivity and capital stock growth rates. Any adverse climate effects (e.g., reduced productivity due to increased temperatures) or big policy effects (e.g., increased capital stock due to policy-stimulated investments) may enter the current policy baseline. Even a tiny shift in the baseline is worth many billions of dollars of tax receipts, and so Stock underscored the importance of accurately estimating the change on the 10-year horizon.

The changing climate will also adjust the distribution of future shocks. Stock noted that research economists have raised concerns about projections lacking uncertainty bands. Although CBO and OMB are aware of this challenge, public communications commonly center around single-number projections. As climate is expected to increase uncertainty in macroeconomic projections, Stock suggested that providing more details on the associated uncertainty is scientifically valuable. Finally, he opined that transition risks will likely be more significant over the next decade than physical risks for the macroeconomy.