Exploring the Bidirectional Relationship Between Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 3 Research and Development Considerations for Neuroscience and AI

3

Research and Development Considerations for Neuroscience and AI

Highlights

- Artificial intelligence (AI) can use data to help interpret neurological and neuroscientific data, redefine diagnostic criteria for psychiatric and neurological disorders, and expand our understanding of disease pathology. (Chang, Wittenberg)

- Open data sharing and access may be needed to allow for the continued progression of AI models and neural decoding research. (Chang)

- Interpretability is crucial to fostering trust, understanding research findings, and tracing model errors back to their root causes. This is especially important for identifying and correcting for unintended biases. (Lancashire, Schaich Borg)

- As AI models advance and become integrated into health care and other sectors, it will be increasingly important to examine their capacity for moral decision making. (Schaich Borg)

- Applying AI to health care problems often requires integrating disorganized, multimodal, and sensitive data—researchers should prioritize addressing this technical and ethical challenge. (Lancashire, Wittenberg)

- In the future, large normative models of the brain could be used to gain rapid insight into brain disorders, but this demands more data than is currently available. (Lancashire, Wittenberg)

NOTE: This list is the rapporteurs’ summary of points made by the individual speakers identified, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to be a powerful tool for good, but it also has great potential for misuse, said Bill Martin, global therapeutic area head for neuroscience for Janssen Research and Development. It is not enough to simply develop cutting-edge technologies; especially as AI reveals more about the brain, he urged researchers to consider what safeguards and ethical guidelines need to be in place to ensure that new technologies are used responsibly.

CO-EVOLUTION OF HUMAN AND ARTIFICIAL MORAL INTELLIGENCE

Jana Schaich Borg, associate research professor at Duke University’s Social Science Research Institute, codirector of Duke University’s Moral Artificial Intelligence Lab, and codirector of Duke University’s Moral Attitudes and Decision-Making Lab, discussed the potential of AI in ethical decision making (Awad et al., 2022). She asked whether, as AI appears to behave more intelligently, it also starts to behave more ethically. While there have been recent examples of large language models (LLMs) learning morally relevant information, she said that these models can (and occasionally do) behave unethically. Schaich Borg pointed out that humans occasionally behave poorly without justification, too, and suggested that interpretable AI models can both help us learn more about human moral decision making and guide people through individual moral judgments.

Her research uses interpretable methods to aggregate the choices that diverse populations make across many different moral scenarios and use this data to constrain AI behavior. One benefit of their interpretable methods, she said, is that they reveal common patterns of morality across individuals. She introduced the concept of a “moral GPS,” an interpretable model that can guide a user through challenging ethical decisions based on training examples gathered while the individual was calm and level-headed. She proposed that a tool like this could be helpful in scenarios like choosing where to allocate scarce medical resources or in hiring decisions. Schaich Borg concluded by emphasizing the importance of striving for morality in AI applications both within and outside of neuroscience.

Maynard Clark, a workshop participant, asked whether innovations in AI could produce moral qualities that humans will want to adopt. Schaich Borg responded that some people would argue that moral judgments should

be objective and mathematical—in which case, AI could make better, less biased ethical judgments than humans. However, she clarified that while she does not hold this view herself, she is hopeful that rigorously tested AI could still aid humans in less strictly mathematical decision making. Another participant, Cynthia Collins, wondered how to create AI systems that don’t mirror the internet’s human biases. The first step, Schaich Borg said, is to build accurate models that can track these biases. Then, researchers can consider what they want the models to correct.

CASE STUDIES OF AI APPLICATIONS IN CLINICAL NEUROSCIENCE

Edward Chang, Joan and Sanford Weill Chair and Jeanne Robertson Distinguished Professor of Neurological Surgery at University of California, San Francisco, shared his research revealing parallels between artificial neural networks and the human auditory system (Li et al., 2023). Specifically, their speech recognition models converged on a hierarchical structure resembling the human auditory pathway. Chang demonstrated that these models were attuned to the language they were trained in, suggesting that model layers corresponding to the highest levels of human auditory cortex represent specific linguistic information. The success of this approach echoes the success of the AI-forward strategy that DiCarlo’s group used to develop models of the mechanisms of human visual processing (Yamins et al., 2014; see Chapter 2), here used by Chang’s group to model the mechanisms of human auditory processing.

John Ngai, director of the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH’s) Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative, asked whether Chang’s speech models could account for individual differences between speakers, like their ability to use Mandarin intonations or English phonemes. Chang clarified that the neural networks are capable of extracting pitch information across both Mandarin and English, and that similar acoustic cues are then processed differently in deeper layers of the network, depending on the language.

McClelland wondered whether researchers could make better models of disorders like semantic degradation if they could access the kind of data Chang accesses in an intrasurgical context. Chang responded that, perhaps counterintuitively, studying language production with high neural resolution has “only created more questions than answers.” Still, he said his group is currently working on correlating brain activity to stimuli other than linguistic concepts.

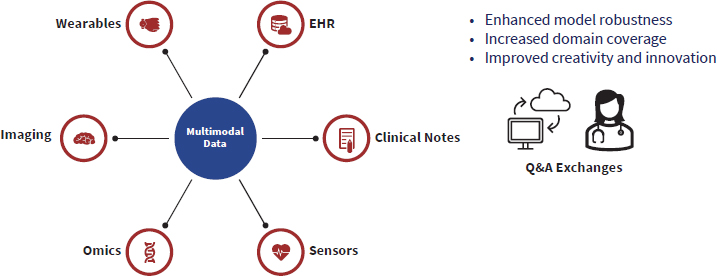

One major challenge that arises when applying AI to neuroscience is handling large amounts of unstandardized, multimodal data. Lee Lancashire, chief data and AI officer at Cohen Veterans Bioscience, discussed systems modeling (see Figure 3-1), which aims to integrate data across

NOTE: Integrating data across multiple scales enables the study of complex biological systems.

SOURCE: Presented by Lee Lancashire on March 26, 2024.

multiple scales to study intricate biological interactions. The goal, he said, is to pinpoint how changes in one part of the system can affect the whole, which is crucial for understanding the complexity of human health. This requires multimodal data, which introduces a host of challenges: different data types may be stored in different locations, and privacy concerns may arise when trying to integrate data across sources.

For example, in his own work, Lancashire used generative AI to integrate data from Parkinson’s disease patients’ electronic health records, which include everything from lab results to unstructured clinical notes (Gerraty et al., 2023). Using this unstructured multimodal data, Lancashire’s team was able to better understand individuals’ disease progression and predict patient outcomes. Using more traditional machine learning techniques, they have successfully predicted states of depression and remission in post-traumatic stress disorder from patient data (e.g., Jeromin et al., 2020).

He ended his presentation by reiterating the importance of transparency and interpretability. “Situations where the decision-making process of these models is not transparent or is not easily understood,” he said, “can lead to mistrust and hesitancy in their adoption,” particularly in health care settings, where decisions impact patient outcomes. To address this, he suggested highlighting which aspects of the data are influencing the model’s decisions when presenting its output, prioritizing informed consent, and rigorously validating models in diverse real-world settings.

HARNESSING LARGE-SCALE DATA FOR PRECISION MEDICINE

Gayle Wittenberg, vice president and head of neuroscience, data science, and digital health at Janssen Research and Development, spoke about

using data to redefine brain disorders from the ground up. Central nervous system (CNS) disorders are largely defined by behavioral changes that occur because of biological dysfunction, and their diagnostic criteria are largely outdated and defined by behavior alone. Because of this, at the biological level, the existing diagnoses are indistinct, making the development of therapeutics that treat biology a challenge. Wittenberg emphasized the need for data-driven realignment of diagnoses and the biological understanding of diseases. This, she said, requires better measurement tools. Distilling the complex actions of 100 billion neurons in the brain into words in the English language can be limiting, and Wittenberg said that even committed patients would not be able to provide self-reported data for something like heart rate variability—but a wearable device can.

She provided several examples where quantitative measurements could provide insight into brain changes that would otherwise be difficult to identify through conversation alone. People experiencing anhedonia, for example, could be assessed by fitting computational neuroscience models to their performance in a reward-driven video game (Pizzagalli et al., 2008). She also shared recent findings that augmented reality tests can collect hundreds of measurements at once, which can train AI models to identify preclinical Alzheimer’s disease (Muurling et al., 2023). “The lesson that this tells us is that when we say something like ‘no symptoms,’ that declaration really depends on what your measurement tool is, and how sensitive it is.”

Today, data exists at scale in electronic health records and insurance claims, but it lacks the level of detail required for precision medicine. Moving forward, Wittenberg urged researchers running clinical trials and, more importantly, health care systems to think about how to collect large-scale patient data while still minimizing costs and protecting people’s privacy and trust. She believes that this will be a slow process but is optimistic about the potential benefits of moving to a learning health care system paradigm.

Cohen commented that, as the field continues using AI models to understand pathology, perhaps the subfields of computational psychiatry and computational neurology could either merge or be used to complement each other. He believes that modeling the brain in this way could reveal fundamental trade-offs inherent to neural architecture, such as that between automatic and flexible behavior.

Martin asked what challenges remain in using AI to diagnose neurological and psychiatric conditions accurately and reliably. Wittenberg reiterated that we need to redefine brain diseases from scratch—not only are existing diagnostic tools imprecise, but different measures are made depending on which historical diagnosis the patient received, which limits the ability to start from data to redefine disease. In the future, she hopes to see models that generate predictions about specific patients’ brains from multimodal, accessible data. Lancashire agreed, and added that capturing the subjective, variable nature of psychiatric illness is still an unmet chal-

lenge. He proposed that incorporating more objective biological measurements may help models make more accurate predictions.

DISCUSSION

Martin asked all the panelists to share the biggest surprises and under-reported developments they’ve seen in AI and neuroscience over the past 3 years. Schaich Borg was surprised by how well LLMs perform at social tasks; similarly, Wittenberg has been astonished by how AI advances in language have led humans to start asking questions about consciousness, where equivalent advances in computer vision, for example, have not. Chang hadn’t expected AI to achieve near-human performance in areas we once thought were unique to the brain, and emphasized how important it will be to use AI to interpret neuroscience data moving forward. Lancashire has been surprised by the paradigm shift in AI from task-specific models to foundational models.

Hill asked how scientists at research institutions can be incentivized to produce the kind of high-quality data needed to train foundation models. Wittenberg responded that building large-scale foundation models should be a community effort. Not only are individual labs ill-equipped to build them alone, but on principle, “it’s not the kind of thing you need to own. It should be a tool that everybody has to work on.” Lancashire suggested collaborating with tech companies to gain access to greater computational infrastructure. Schaich Borg agreed and added that having more centralized resources would help to protect data from privacy attacks.

Michele Ferrante, who works in the computational psychiatry program at the National Institute of Mental Health, expressed concern for the lack of protections against adversarial attacks against biomedical data repositories. This could result in models becoming corrupted, and it’s currently very difficult to detect if the data is nefarious. He wondered if there was anyone working on this challenge in the neuroscience field. Wittenberg said that one approach she had seen was tracking the distribution of model outputs in response to the same data over time, to see whether the model’s deployment was shifting.

An online participant asked what makes a model interpretable versus a “black box.” Lancashire said methods that extract and visualize feature importance, or what pieces of information most strongly guided a model’s decision, can help explain the reasoning behind a model’s predictions. Understanding which features the model prioritizes, he added, can also inform the development of simpler models. Another option is to use rule-based models, which are constrained to construct algorithms readable and interpretable by humans, Wittenberg said. However, these models don’t perform as well as larger, less interpretable models. She added that the need for

interpretability may depend on context. A model deciding whether someone should or should not be released from prison, for example, should be highly explainable—but some lower-stakes situations may not necessitate the same level of transparency. Schaich Borg also stressed the importance of interpretability in service of accurately tracking bias and other unintended outcomes. Sejnowski proposed visualizing features of deep learning networks as one method of increasing interpretability.

Martin asked Chang and Schaich Borg how neural decoding can improve human–computer or interpersonal interactions. Chang emphasized that neural decoding could benefit people who have lost their ability to move or communicate, but access to more centralized open-source data will be necessary to move this research forward. Schaich Borg pointed out that the field has yet to consider how AI-driven products will shape our human-to-human connections. She believes that AI could be used to help understand how humans build social connections and how those connections can be strengthened.

The panel ended with a final question from Haas, who wondered whether one could rapidly gain insight into brain disorders by building massive AI-driven normative models of the brain and systematically running ablation experiments in silico. Lancashire said it will be challenging to define “normal” without access to massive datasets. He pointed out that large datasets like the UK Biobank are already available (Collins, 2012). The challenge moving forward will be integrating these datasets to build models.

This page intentionally left blank.