Exploring the Bidirectional Relationship Between Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 5 Communication and Engagement with the Public and Individuals with Lived or Living CNS Disorder Experience

5

Communication and Engagement with the Public and Individuals with Lived or Living CNS Disorder Experience

Highlights

- Neurotechnology developers can consider designing systems that appeal to the mass market, beyond clinical trial participants. Considering the broader needs of intended user populations can propel products toward acceptance and adoption. (French)

- Instrumentive artificial intelligence (AI), intended to augment human capabilities rather than make autonomous decisions, can streamline clinical workflows and increase clinicians’ capacity for direct care. (Guggemos)

- The user interface of an AI tool is as important, if not more important, than its underlying algorithms. (Hoque, Wilbanks)

- Incorporating potential users at every stage of the design process will help developers earn trust and build more effective systems. (French, Gonzales, Hoque, Wilbanks)

- More diverse, representative datasets and engineers are needed to reduce biases in AI tools. (Gonzales)

- To increase public understanding, regulators and policymakers can emphasize clear, simple communication around AI regulation and fund initiatives to increase AI literacy. (Gonzales, Wilbanks)

NOTE: This list is the rapporteurs’ summary of points made by the individual speakers identified, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Katie Sale, executive director of the American Brain Coalition, said that individuals with lived or living experience with central nervous system (CNS) disorders—the intended users of many neurotechnologies—perceive artificial intelligence (AI) very differently. Some feel empowered and hopeful about the potential of emerging neurotechnology, while others more strongly feel skepticism, fear, and frustration. The panelists examined how neuroscientists and AI engineers can work together to educate the public about the use of AI in research, clinical care, and general applications. They also explored how to best reach historically underserved and underrepresented communities, both in general communication campaigns and in the technology development process.

AI APPROACHES TO USER-CENTERED NEUROTECHNOLOGY

French spoke about integrating advocacy and education into neurotechnology development. She distinguished between two types of systems in neurotechnology: individualized closed-loop systems (such as deep brain stimulation), which use a person’s own data to train their device to improve, and multidata systems, which use crowdsourced brain data to better understand health and neurological diseases at a population level.

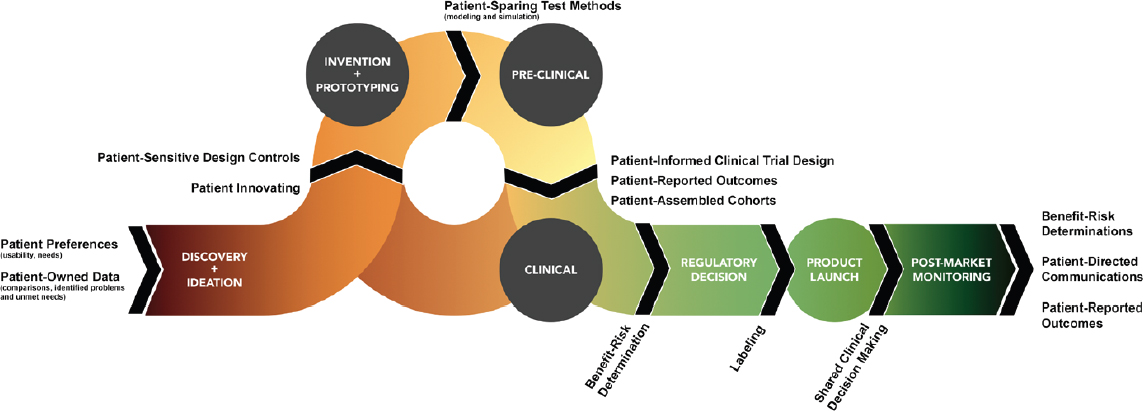

Neurotechnology developers tend to build systems for early adopters, like clinical trial participants, but French urged the audience to think about how to build systems for the mass market. She also pointed out that much of neurotechnology is built around a medical model, which frames patients as a cluster of limitations and treatment needs, but we should also think about a social model, which shifts focus away from the individual deficiencies and toward structural and systemic barriers that people with disabilities face. These changes could help new technologies move past initial market approval to acceptance and adoption. French said that including the community early in the development process—long before a product is on the market—is necessary to make sure products are effective and accessible (see Figure 5-1). She ended her presentation by mentioning the Implantable Brain-Computer Interface Collaborative Community (Mass General Brigham, 2024), launched in early 2024, which is bringing together stake-

SOURCES: Presented by Jennifer French on March 26, 2024, from Benz and Civillico, 2017.

holders in industry, patient advocacy, community engagement, research, and clinical care to address systemic problems in this space.

Speaking to the different ways users can interface with AI, Matthew Guggemos, co-founder and chief technical officer of iTherapy, LLC, discussed the role of instrumentive AI in health care and education. He distinguished between agentive and instrumentive AI. Agentive AI makes fully autonomous decisions, while instrumentive AI aims to extend human capabilities (Guggemos provided an example of instrumentive AI use as an adult with autism using a chatbot to practice for a job interview). Instrumentive AI, he said, can help simplify burdensome tasks like speech transcription and data analysis, empowering clinicians to spend more time on direct patient care. He added that AI-based tools can also help diagnose health conditions and connect patients to care, but establishing trust will be necessary before AI can be widely integrated into medical settings. Guggemos emphasized the importance of transparency in research, communication with the public, and interdisciplinary collaboration.

CASE STUDY: PATIENT-CENTERED AI FOR PARKINSON’S DISEASE

Ehsan Hoque, associate professor of computer science at the University of Rochester and co-lead of the Human-Computer Interaction Lab, presented recent work from his team as a case study of designing AI to diagnose neurology patients and discussed the challenges they’ve faced building relationships with the community they’re trying to help. His group noticed that diagnosing Parkinson’s disease currently requires an in-person exam that takes several hours, which, given a limited number of doctors, leads to months-long wait times for patients.

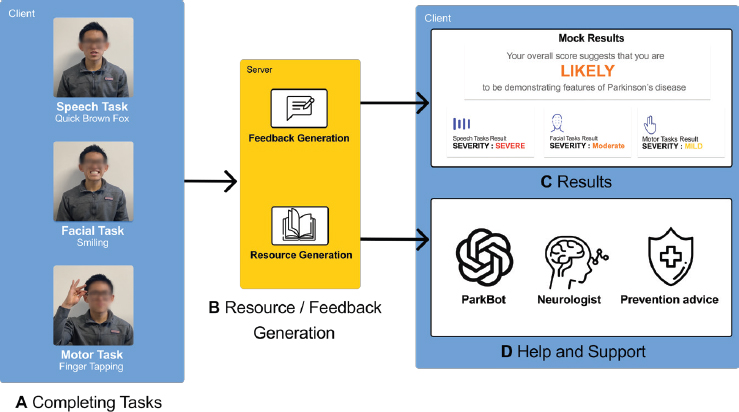

To address this problem, Hoque’s team built an algorithm that can screen for Parkinson’s disease and assess symptom severity via webcam. “But that was the easy part,” he said. The bigger challenge was figuring out how to communicate results clearly and sensitively to the user (see Figure 5-2). His team added an interface that communicates disease risk to patients in plain language, and a large language model (LLM)–powered chatbot to answer questions and provide resources (while safeguarding against misinformation). They received positive feedback from patients and learned that interpretability was especially appreciated.

NOTE: Users are guided to complete three sets of tasks to assess Parkinson’s disease risk, and recorded videos are passed to a server that processes them and generates feedback. A breakdown of performance and assessment of Parkinson’s disease risk are displayed to users, along with resources like a specially trained chatbot and connections to local health care providers.

SOURCES: Presented by Ehsan Hoque on March 26, 2024, from Rahman et al., 2024.

ENGAGING HISTORICALLY UNDERSERVED COMMUNITIES

Susan Gonzales, founder and CEO of AIandYou, urged people working in AI to broaden datasets to reflect more historically marginalized communities, especially in health care. Gonzales coauthored a World Economic Forum report (2022) encouraging AI developers to “slow the train down a bit,” develop models with broader datasets, and include stakeholders throughout the development process. She encouraged leaders in the field to consider bringing more perspectives into their decision-making processes. The long-term solution, she said, would be to recruit people from more diverse backgrounds to contribute to the code behind AI.

John Wilbanks, head of product for the data sciences platform at the Broad Institute, senior advisor to the Milken Institute’s FasterCures, and senior fellow at the Datasphere Initiative, discussed the importance of considering the user experience during AI development.

While many audience members understood neural networks, he said, only a couple identified as having direct or indirect experience with a CNS disorder; “the average experience of someone living with a CNS illness, or

caregiving for someone, is not one that leads you to understanding mathematics.” He argued that product managers, who interface between users and engineers, need “to be part of every government grant that goes into AI that touches human beings.”

In Wilbanks’s experience working with underrepresented minorities as part of the All of Us research program, he heard community concerns that AI developers may only be sharing the benefits of AI and not the limitations or risks. These communities wanted to be a part of the conversation about the risks, and that radically changed Wilbanks’s approach to informed consent (NIH, 2024). He advocated for funding user research whenever AI is funded and for situating technology within the community it aims to serve. “There is a big difference between applying technology to or on a community, and facilitating technology to come out of a community,” he said. Currently, it’s challenging for people to apply for National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding without a doctoral degree, and a funding mechanism that considers applicants without PhDs, he said, could help people develop more community-situated technology. He concluded, “AI is thinking about language before meaning. How do you close that gap? You close it by talking to human beings and feeding it back into the loop.”

DISCUSSION

Sale asked what actions can help build trust between developers and users. French emphasized the importance of co-development and said, “If we build a tool with the community in mind, then they build trust in the system.” Gonzales added that before building trust, developers have a responsibility to educate communities affected by their research. Before people can trust new technology, she said, they need basic AI literacy. Wilbanks shared that, in his experience, dropping into a community as a government representative who doesn’t share the community’s identities results in wariness. He suggests working through trusted institutions within communities and being consistent with stated values throughout research and development—even when it slows the publication process. Hoque and Guggemos agreed that bringing in potential users from the start of the development process is key, even if it introduces new workflow challenges.

Sejnowski wondered why AI startups don’t outsource data collection to other companies, who could gather information from communities on their behalf. Relatedly, another participant asked whether the concerns raised in this workshop surrounding community engagement are unique to AI. In response to the latter question, Wilbanks said that it’s a matter of scale. For example, a patient struggling to find information about their rare disease from another source might turn to ChatGPT for answers—if the chatbot

provides a hallucinated answer, there’s no way to stop that information from traveling from that patient to others through word of mouth.

Sale asked whether there should be different messaging standards when discussing AI with children versus older adults. Hoque said that his three-year-old son is so comfortable with digital technology that he tries to interact with still photographs as though they are touch screens. His older Parkinson’s disease patients, on the other hand, struggle to use a keyboard. Given his own observations, Hoque agreed that AI messaging and user interfaces should be tailored to the lived and living experiences of users. French and Litt added that engaging a broad range of populations, and demonstrating success when it happens, can foster continued participation in the AI community and lead to greater adoption of products once they are approved.

Schaich Borg asked what infrastructure exists to help researchers get feedback from people who will be affected by their work. Wilbanks proposed that the NIH fund a pool of user interviews, journeys, and personas that researchers could draw from, rather than starting from scratch with every study. Gonzales emphasized that, in addition to working toward long-term policy changes, researchers can start conversations with stakeholders outside the research community. In his experience as a professor, Hoque shared, “It’s difficult for me to excite my students to do community engagement work, because it doesn’t further the goal of getting a job in OpenAI.” He proposed creating more incentives for early-career researchers to focus on community engagement work and participatory research. Cohen proposed that AI could be used as an instrument to study how to make AI more accessible.

French emphasized that the term “patient” itself can be limiting. “That just resonates within the medical model, and we live outside that,” she said. In other words, a person living with a CNS disorder is more than just a “patient” and has many identities outside of that. French added that neuroscientists and engineers need education on community engagement to equip them to learn not only from clinical trial participants but also from their family networks and communities more broadly.

Making AI Literacy Accessible

Panelists discussed strategies for increasing basic AI literacy, given that AI is an unprecedented and rapidly evolving topic that many people don’t initially view as relevant to them. Gonzales shared that the U.S. government is considering a national AI literacy awareness campaign (NAIAC, 2023) and emphasized the importance of educating frontline workers like nurses and educators who interact directly with other members of the community.

Hoque highlighted the need to simplify existing ethical AI frameworks, which are currently too technical for many clinicians to digest easily. French suggested looking outside current models of education and community outreach. She provided the example of one community advocacy organization that reached a broader community by first finding established community leaders and distributing information through them. Guggemos added that public–private partnership could be another option, given how much trust nonprofit organizations tend to have within their communities.

Wilbanks suggested incorporating AI literacy training into community college curriculums, which Sejnowski proposed could scale to massive open online courses. Gonzales cautioned that “this is not a ‘build it and they shall come’ situation,” in that historically marginalized communities aren’t inherently curious enough about AI to go out of their way to learn about it. An ongoing challenge, she said, will be to garner more public interest in the issue and to find ways to meet people where they’re at. French underscored the importance of making sure that education platforms are accessible, particularly for people who are using assistive technologies, to ensure that people with disabilities aren’t left behind.