Exploring the Bidirectional Relationship Between Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 4 Impact of AI in Medical and Clinical Environments

4

Impact of AI in Medical and Clinical Environments

Highlights

- To solve medical problems that require massive amounts of data processing, academic researchers need access to large-scale computing resources on par with private companies. (Fang, Litt)

- If trained on representative data and rigorously validated, fully autonomous artificial intelligence (AI) has been shown to reduce bias and human error in clinical settings. (Abràmoff)

- Disease-specific models trained on large populations of patients can be used to predict individual treatment outcomes. (Litt)

- While foundational AI models were largely inspired by the visual system, building in elements of high-level cognition will help create better models of human disease. (Fang)

- Conversational chatbots for psychotherapy can fill gaps in mental health care access, but more work is needed to understand how humans relate to AI therapists. (Darcy)

- Converging on a unified vision for AI in health care, complete with technical specifications and process standards, will help developers earn the public’s trust. (Anderson, Darcy)

- Developers and regulators could consider how to monitor AI tools after they launch and define performance criteria for their continued use in clinical health care workflows. (Anderson)

NOTE: This list is the rapporteurs’ summary of points made by the individual speakers identified, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Jensen shared that the objective of this session was to discuss what health professionals and people who engage with the health care system want and need from medical applications of artificial intelligence (AI). Panelists explored how people working in brain health can help develop representative, innovative, and effective AI for health care.

BIDIRECTIONAL RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN AI AND MEDICINE

Ruogu Fang, associate professor and Pruitt Family Endowed Faculty Fellow in the J. Crayton Pruitt Family Department of Biomedical Engineering at the University of Florida, discussed the impact of AI in medicine. She pointed out that while AI was historically inspired by human intelligence, there are gaps between our expectations of AI and reality. For instance, AI has largely modeled the visual system without considering elements of high-level cognition like reasoning, emotion, and executive function. She proposed that building high-level cognition into AI models will help create disease models that can help clinicians diagnose brain pathology.

Fang suggested that individuality should be built into generalist models, such that any model could be converted into a personalized precision model for a patient, given their unique features. She also emphasized the importance of understanding the sources of bias in medical AI models and to find ways to regulate models accordingly. Echoing a point made in earlier sessions, Fang said that AI models and neuroscience principles can inform each other in a feedback loop that can help researchers build better AI models for health care (see Figure 4-1). She concluded by calling for long-term continu-

SOURCE: Presented by Ruogu Fang on March 26, 2024.

ous funding for neuroscience-inspired AI and AI-empowered brain health research and for large-scale computing resources for academic research.

CASE STUDIES OF AI IN THE CLINIC

Michael Abràmoff, Robert C. Watzke Professor of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at the University of Iowa and founder and executive chair of Digital Diagnostics, spoke about the use of autonomous AI in health care. Autonomous AI, or algorithms that make medical decisions independently, is the fastest-growing AI in clinics based on patient use (Wu et al., 2023). He described a fully autonomous AI tool his team developed to diagnose diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema (Abràmoff et al., 2018). This AI is robust against racial bias and more accurate than highly trained retinal specialists like Abràmoff himself is. Importantly, he said, with tools like this, medical liability lies with the AI developer, not with the physician using it.

He contrasted this with assistive and augmentative AI (see Table 4-1), which aids health care professionals but leaves final decisions up to the human clinician. While assistive AI can only help patients who are already connected to a health care provider, he said that there is now evidence that autonomous AI can both improve diagnostic accuracy and increase health care accessibility for people who aren’t currently receiving care (Abràmoff et al., 2021; Wolf et al., 2024). Digital Diagnostics’ tool is simple, explainable, and free of racial bias, which helped them get Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval. Developing this technology, Abràmoff said, was a decades-long process, with the FDA and other regulators involved throughout.

AI can also aid in the diagnosis and monitoring of conditions beyond ophthalmology. Brian Litt, Perelman Professor of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Bioengineering at the University of Pennsylvania, presented a case

TABLE 4-1 Distinctions between Autonomous and Assistive AI

| Assistive and Augmentative AI | Autonomous AI | |

| Medical decision made by | Clinician (with AI guidance) | Computer (without human oversight) |

| Liability | Clinician | AI creator |

| Accessibility | Patient must already be receiving care | Can reach patients anywhere |

| Real-world potential | Improves outcomes for existing patients | Improves outcomes for patients and populations more broadly, addressing health care inequity |

SOURCES: Presented by Michael Abràmoff on March 26, 2024, from Abràmoff et al., 2022, and Frank et al., 2022.

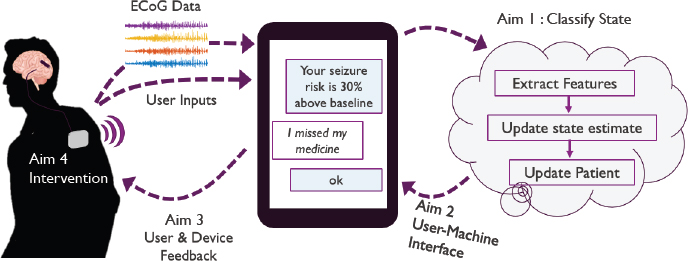

NOTE: ECoG = electrocorticography.

SOURCE: Presented by Brian Litt on March 26, 2024.

study of an AI-driven solution to epilepsy treatment. Today, clinicians rely on their own literature review and personal experience to make diagnoses. But, he said, “Why shouldn’t they [patients] be compared to the thousands of patients that are having epilepsy surgery every year?” He described a study conducted by his research group, where they trained large language models (LLMs) on clinical notes and other patient data to predict long-term epilepsy outcomes (Xie et al., 2022, 2023). In another study, his team aggregated intracranial electrode data gathered from patients across institutions to predict where in the brain new patients should have epilepsy surgery (Bernabei et al., 2023). He also discussed the potential for management devices with AI-powered chatbots to interface directly with users and their medical devices (see Figure 4-2). For example, the chatbot might say: “I just saw a change in your background neural activity that suggests you may have a seizure within the next hour,” noted Litt.

Technology like this is necessary, Litt said, because patients have limited access to expert care. However, barriers like siloed data, potential security breaches, and other AI risks still present challenges. He proposed modernizing laws to better accommodate the evolving digital landscape and incentivize academics and companies to share data. Litt concluded by underscoring the importance of public–private partnerships for acting on the knowledge that medical data can provide.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR AI-DRIVEN HEALTH CARE

Alison Darcy, founder and president of Woebot Health and adjunct faculty member in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford’s School of Medicine, spoke about the potential for conversational

chatbots to deliver effective, accessible psychotherapy. Woebot Health, founded in 2017, developed a conversational chatbot called Woebot that uses concepts from cognitive behavioral therapy to help people challenge and reframe negative thought patterns. She said that this is something chatbots can be great at, and her team found that Woebot creates a bond that is comparable to that achieved by human therapists in more traditional settings within 3 to 5 days of conversation and helped clinical trial participants reduce symptoms of depression (Fitzpatrick et al., 2017; Suharwardy et al., 2023).

Before addressing ethical questions of whether chatbots should be used in this way, Darcy said that we need to understand how they are developing therapeutic relationships with humans. She ended with her concerns about the expectations people have of AI-based mental health tools. There are hundreds of thousands of apps claiming to have mental health impacts, but very few are backed by science—she wondered whether this will undermine public confidence in this emerging technology.

ESTABLISHING BEST PRACTICES FOR AI IN HEALTH CARE

Brian Anderson, chief executive officer for the Coalition for Health AI (CHAI), discussed the history and current mission of his organization. While many tech companies and academics are doing excellent work to define responsible AI frameworks within their respective silos, Anderson said that a consensus perspective has yet to emerge. He emphasized that this is especially important in health care, given the need for AI in that space, and the public’s lack of trust in AI. CHAI aims to address this by creating public–private partnerships between academia, technology companies, governmental organizations, clinicians, and patient community advocacy groups. Rather than simply define high-level concepts like fairness and transparency, he said that CHAI’s working groups will develop technical specifications and process standards to inform the development, deployment, and maintenance of AI over time.

The deployment and monitoring stages are especially important in health care, Anderson noted. We need to ask how AI will be integrated into clinical workflows, how often it will be monitored, what that monitoring looks like, and how to define the performance threshold for pulling a model from use. Other questions surrounding fairness, like how to identify and correct for a biased model, need to be answered as well. He ended by restating the importance of bringing together working groups to draft best-practice frameworks for industry and regulators to use as AI evolves.

Cohen asked whether CHAI engaged with cognitive scientists or neuroscientists. Anderson believes some of more than 2,100 organizations

working with CHAI are cognitive scientists and neuroscientists doing basic research on AI systems, and he invited workshop participants to join.

DISCUSSION

Jensen moderated a panel discussion and audience Q&A focused on the integration and potential impacts of AI in health care, particularly in neurology and psychiatry. Overall, panelists were optimistic about AI’s ability to boost efficiency in medical screenings and minimize health disparities. Fang thinks that AI could be especially helpful in early diagnostic screening, and Darcy is optimistic that conversational AI-powered chatbots can make mental health support more accessible. However, there were concerns about how mistakes made by AI tools will be handled and whether the introduction of these tools could inadvertently lead to more human error.

Barch asked panelists what issues they felt were specific to AI, beyond issues pertaining to data management in health care. Litt said that he thought of AI as a powerful search tool that can collect and synthesize large amounts of information. This can be a strength because it provides information based on a broad collection of literature, but Litt pointed out, if AI is trained on poor data, then the output may not be good.

Relatedly, other participants asked how regulators can be nimble and iterative as AI advances and datasets grow and how regulators should consider the competitive nature of medical systems in the United States. Abràmoff said that developers need to build products with patient outcome needs in mind and advance deliberately enough to garner their trust. Anderson mentioned a rule recently announced by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology that established unprecedented transparency requirements for AI used to manage health data (HHS, 2023). All agreed that regulating AI is necessary to protect patients. Anderson said that one strength of this rule is that, while it was built around the current AI ecosystem, it is meant to cover emerging AI capabilities and use cases as they arise.

Schaich Borg asked what guardrails should be in place when deploying AI in clinical settings where it might guide a clinician’s decision making. Abràmoff pushed back against the idea that human clinicians should be held up as the standard of clinical decision making and argued that the focus should instead be on patient outcomes. Autonomous AI has been shown to reduce human variability in clinical outcomes (Abràmoff et al., 2022). Fang said that taking time to create well-validated AI systems is crucial to giving clinicians tools that will help streamline time-consuming tasks like image segmentation. She also pointed out that, if an AI system leads a clinician to make a mistake, it’s important to evaluate the root cause to see

whether the AI is being trained poorly, the clinician was not experienced enough, or something else.

Transparency in Data and AI Systems

Patel asked for CHAI’s perspective on how to address incorrect predictions or other errors made by AI. Several panelists agreed that transparency is crucial to minimizing mistakes and assessing the mistakes that do happen. Anderson also emphasized the importance of getting informed consent from patients and ensuring that they are educated about the pros and cons of AI tools involved in their care. He shared that CHAI focuses on transparency at the data input level, helping providers understand how models are trained and on what populations they will be most effective. Anderson and his team at CHAI are working to build a system where labs partner with health care systems to test AI models for regulatory approval.

To increase transparency, Litt proposed creating a data ecosystem that connects well-defined, interpretable models, rather than solely focusing on large, obfuscated general models. Fang agreed that testing models is critical but suggested that developers should have to report a model’s decision confidence in addition to accuracy. This, she argued, could help clinicians make informed decisions about how much autonomy to grant AI tools. Darcy said that Woebot prioritizes individuals’ participation in the prediction-making process. As an example, she said, “If Woebot is making a prediction, Woebot will say, ‘I’m understanding [what] you’re sharing as fundamentally a mood problem or relationship problem. Is that true?’” This not only increases algorithmic accuracy but also ensures the interaction between the individual and Woebot is empathetic, Darcy concluded.

The Use of AI in Medical Environments

One area where AI can be especially helpful, Darcy believes, is psychotherapy. The field has historically struggled with a lack of data, and she proposed that AI-driven platforms can help clinical researchers gather enough data to systematically evaluate what treatments work, and under what circumstances. Litt was optimistic about the future role of AI in medical recordkeeping. Medical records are currently highly variable and disorganized, and replacing narrative notes with more objective measurements, like passively collected cell phone data, could help doctors better understand their patients. However, several panelists emphasized the importance of high-quality data, with the adage “garbage in, garbage out.”

DiCarlo asked whether there were any benchmarking platforms in place for evaluating models of human emotion, like there are in other

AI subfields like visual object recognition. Darcy provided Woebot as an example: their AI chatbot asks people for their emotional state regularly, allowing it to build a rich behavioral dataset. These data, in conjunction with data on their outcomes if hosted in open science benchmarking platforms, could help developers evaluate how well their algorithms work.

The Ability of AI to Mitigate Health Disparities

In response to a question from Jennifer French, executive director of Neurotech Network, about how AI is addressing health disparities, panelists emphasized the importance of training models with representative datasets. Darcy said that her team’s research on Woebot oversamples for racial and ethnic minorities, and they have found that uninsured young Black men tend to use their product most efficiently. She suggested that, at least anecdotally, marginalized groups are sometimes more comfortable talking to an AI chatbot about their mental health concerns than a human therapist because it removes the “sociocultural baggage” usually imposed on them. In his own research, Litt has also found differences in the effectiveness of health care by zip code, a proxy for income level.

Abràmoff said that, if trained and implemented properly, autonomous AI has been shown to remove health disparities (Wolf et al., 2024). Anderson added that CHAI is activating networks of health centers that serve unreached, underserved populations to provide AI developers with more representative datasets.

Throughout the discussion, panelists emphasized that improving clinical outcomes for the patient should always be the goal and that innovation should center patient needs. The panelists also restated the need for careful validation, auditing, and transparency of AI systems to ensure that they are safe and effective and that errors are traceable when they occur. Jensen concluded by stating that the panelists demonstrated that clinical neuroscience, neurology, psychiatry, and neurosurgery could be best positioned to test AI in clinical environments moving forward.