Exploring the Bidirectional Relationship Between Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 6 AI Regulation, Policy Advocacy, and Engagement

6

AI Regulation, Policy Advocacy, and Engagement

Highlights

- Researchers and regulators need to have conversations about laws protecting neural data privacy because current laws are overlapping, over specified, and underinclusive. (Farahany)

- The Global Initiative on AI for Health is producing frameworks for evaluating artificial intelligence (AI) health projects and hopes to foster an international community focused on AI fairness and safety. (Weicken)

- Because AI is evolving rapidly, regulatory bodies can plan for flexibility, both in funding decisions and in controlling risks surrounding data privacy, bias, and liability. (Farahany, Ngai)

- Increased dialogue between researchers and clinicians is needed to develop evidence-based policy guidance. (Shen)

- A complete understanding of AI decision making is not a prerequisite for developing systems to audit AI systems in health care. (Shen)

NOTE: This list is the rapporteurs’ summary of points made by the individual speakers identified, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Michael Littman, division director for Information and Intelligent Systems at the National Science Foundation and University Professor of Computer Science at Brown University, emphasized the need for a shared research vision and shared computational infrastructure, data, and models, referencing the National Science Foundation’s implementation of a National Artificial Intelligence Research Resource Pilot (NAIRR Task Force, 2023). He encouraged researchers, particularly in artificial intelligence (AI) and computer science, to engage in “field-wide priority development” to help solidify a concrete set of requests to bring to the public. Littman also suggested that the National Academies put together a decadal report on the state of AI, as has been done for other fields—including neuroscience—in the past. The panelists reviewed current and proposed AI regulation and discussed how neuroscientists and computer scientists can collaborate with policymakers to ensure the responsible use of AI.

NEURAL DATA PRIVACY CONSIDERATIONS

Nita Farahany, Robertson O. Everett Professor of Law and Philosophy, director of Duke Science and Policy, and chair of the Master of Arts Program in Bioethics and Science Policy at Duke University, discussed ethical considerations surrounding neural data privacy. In her book The Battle for Your Brain, Defending Your Right to Think Freely in the Age of Neurotechnology (Farahany, 2023), Farahany advocated for a right to self-determination over our brains and our mental experiences. She argued that the field urgently needs to have conversations about laws surrounding cognitive liberty “so that we don’t end up with a lot of overlapping, over specified, and underinclusive laws that don’t actually achieve the kinds of privacy rights that we’re interested in but do frustrate innovation and create lots of problems going forward.”

She highlighted one legal trend—carving out exceptions for neural data, such that it’s treated differently than other data—as especially problematic. The EU AI Act1 has provisions in place for sensitive and biometric data, but Farahany points out that specific exceptions are being made with respect to this kind of data in U.S. AI legislation. “This creates overlapping and conflicting potential requirements between the way we think about sensitive data under AI, and the way we think about neural data as a carve-out under these different and overlapping laws,” she said. The United States has other laws handling biometrics, however, which she said further muddies neural

___________________

1 For more information on the EU AI Act, see https://artificialintelligenceact.eu/ (accessed June 3, 2024).

privacy protections. She called for a convergence of AI, neuroscience, and legal policies to better protect privacy rights without hindering innovation.

CASE STUDY: GLOBAL INITIATIVE ON AI FOR HEALTH

Eva Weicken, chief medical officer in the Department of Artificial Intelligence at the Fraunhofer Heinrich Hertz Institute for Telecommunications in Berlin, discussed the work of the World Health Organization (WHO)–International Telecommunications Union–World International Property Organization’s Global Initiative on AI for Health (WHO, 2023). The initiative aims to develop international standards, best practices, and an assessment framework to ensure that AI is used safely, effectively, and inclusively.

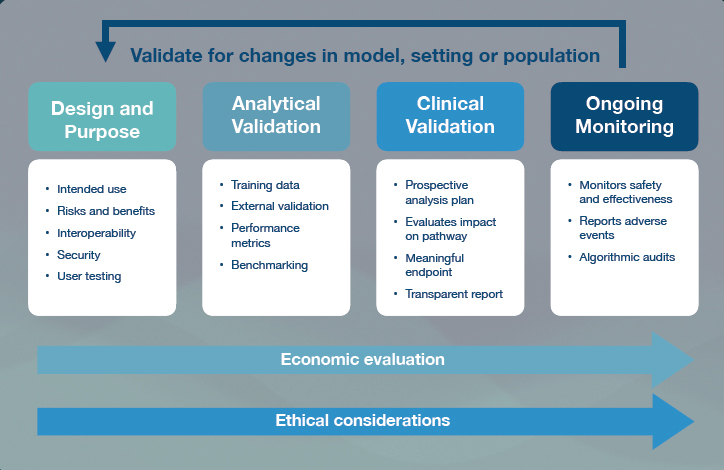

She said that the initiative’s interdisciplinary team of more than 100 people has met 21 times so far, and different working groups have produced guidance documentation including frameworks for evaluating AI in clinical settings (see Figure 6-1) and benchmarking standards for the AI-assisted assessment of different diseases. They’ve also developed open-source software to help implement these potential solutions. Moving forward, the

SOURCES: Presented by Eva Weicken on March 26, 2024, from ITU/WHO Focus Group AI for Health Working Group, 2023.

Global Initiative on AI for Health hopes to create global community for AI health projects and create sustainable funding for low- and middle-income countries that want to participate.

BALANCING REGULATION AND INNOVATION

Ngai presented the challenge of responsibly navigating the rapidly evolving world of AI without unnecessarily restraining researchers. He shared examples of recent groundbreaking studies in which novel AI approaches are being used to decipher complex brain activity such as the semantic meaning of sentences (Tang et al., 2023), the melody of a song (Bellier et al., 2023), and speech (Metzger et al., 2023). Ngai said that a big challenge will be scaling up the results of small clinical trials to reach the broader population. He emphasized the importance of protecting people’s data while still enabling rapid innovation.

Wade Shen, director of the Proactive Health Office at the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health, discussed the need for researchers, regulators, and policymakers to carefully consider the societal implications of rapidly developing AI technologies. In his previous role as the director of the National AI Initiative Office in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, his team grappled with how to best use AI to solve critical problems while managing potential risk. Because AI is evolving so quickly, he said, we need to plan for flexibility, both in terms of making good investments in technology development (including in early-stage research), and in terms controlling risks (especially surrounding data privacy, bias, and autonomous decision making). He ended by inviting input from AI stakeholders to develop AI regulation and security, especially in health care.

DISCUSSION

Considerations for Future Regulatory Policies

Littman started by asking participants whether they worried AI regulations might interfere with neuroscientists’ ability to do their work. Farahany pointed out that the lack of policy cohesion across nations creates a chaotic overlap of AI, biometric, and privacy laws, which creates a burden for researchers trying to navigate the regulatory systems governing their work. She highlighted data privacy as a particular area of concern because even de-identified data is becoming easier to trace back to its source. To maximize user safety, she suggests approaching the problem both in terms of data processing and storage and in terms of secondary processing and sharing.

Vikram Venkatram, a research analyst at Georgetown University Center for Security and Emerging Technology, asked how conflicting AI regulations will be resolved between countries and within the United States. In response, panelists reviewed strategies governments are taking to balance the needs of different stakeholders regarding emerging technologies. Weicken said that, when developing the EU AI Act, policymakers got feedback from stakeholders and other community members first. She highlighted a project in the EU that provides “regulatory sandboxes,” where developers and regulators can work together to explore an AI system in a testing environment and increase trustworthiness and usability.

Farahany contrasted this approach with the United States, where regulators tend to focus on the market and innovation, and China, where regulations begin looser and expand as necessary (rather than over-regulating upfront). To reconcile these different approaches, Shen suggests that representatives from different countries assess the risks posed by AI and identify what outcomes they hope to achieve through regulation. He suspects that most of the world will agree on at least some of these points, whether they tend to be more commercially driven or not. He said, “I think the outcomes, in my mind, are probably more important as a starting point than the process by which we meet them.”

Zach McKinney, lead reviewer of medical devices at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), sparked a discussion about how regulators should think about handling information, as opposed to the safety of traditional medical devices and drugs. Farahany suggested that the broad secondary harms that could come from the misuse of data, beyond technical aspects of AI or data itself, will be important for the FDA and others to consider. Ngai said that the Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies® (BRAIN) Initiative supports empirical research and employs a neuroethics working group to inform their work.2 He said that the issue of data privacy has grown increasingly pressing and that it has been “eye-opening” to see, despite widespread concern about data privacy, how willing some participants have been to make their data public.

Auditing AI Technology

Patel asked how the government is approaching the challenge of auditing technology that we do not yet fully understand. Shen replied that the government needs to fund research and development that helps make emerging technologies more reliably safe and trustworthy—outcomes that

___________________

2 For more information on the NIH’s Neuroethics Working Group, see https://braininitiative.nih.gov/about/neuroethics-working-group (accessed June 4, 2024).

we are currently capable of evaluating, even without the technical capacity to audit AI decision-making processes. He said that, in the case of software, even when it isn’t possible to know that a given piece of software will perform exactly as planned in the real world, there are many cybersecurity mechanisms in place to mitigate risks. Shen suggested that regulators adopt a similar strategy in the AI space.

Litt suggested that perhaps an “individual data bill of rights” should be adopted to prevent people from misusing data and that large companies should bear at least some responsibility for negative effects of their products. Farahany agreed and added that one way to prevent data misuse is to have multiple layers of protection, such as keeping data on the device that’s processing it and minimizing data brokers’ access to information gathered by large tech companies.

Rights of AI Agents

Cohen pointed out that as AI models begin to gain agency, properly balanced and nuanced approaches to regulation that weigh ethical considerations concerning both the potential risks and benefits of AI technologies will be important. Additionally, he said, there needs to be consideration given to the ethical consequences as well as protections given to basic research and the study of these models, particularly within the context of neuroscientific research. In response, McClelland asked about the rights and responsibilities of AI agents themselves, which may become a concern as the technology continues to advance. Farahany agreed that discussing the issue is important, but it is still unclear how developers will determine how to treat AI models as they gain more agency (and, perhaps, consciousness or sentience). Ngai compared the debate to the one surrounding animal research, where public opinion on ethical boundaries and acceptable behavior evolves over time. He emphasized that, in creating regulation, active public engagement and education will be crucial to having productive, well-informed conversations moving forward. Weicken added that it is also important to consider that different countries may have varied approaches and encouraged the prioritization of collaboration. McClelland strongly argued against giving machines any rights and believes that responsibility for their actions should lie with the corporate entities creating them. Shen said that, because we don’t understand the kinds of social risks emerging technologies will pose in the future, regulations will need to be flexible enough to adapt quickly to changing circumstances. He concluded by urging attendees to engage directly with the government and with regulators to help shape policy decisions.