Reforming the Coast Guard's Certificate of Compliance Program for Liquefied Gas Carriers: Promoting Efficient Implementation and Safety Effectiveness (2024)

Chapter: 3 The Certificate of Compliance Program and the Safety Framework for Liquefied Gas Carriers

3

The Certificate of Compliance Program and the Safety Framework for Liquefied Gas Carriers

The safety framework for gas carriers visiting U.S. ports was developed in the 1960s and 1970s in response to growing concerns about environmental protection and safety for the ships, ports, and surroundings. What began in the United States has now developed into a global and comprehensive approach to gas carrier safety with international standard-setting practices adopted by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and the liquefied natural gas (LNG) and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) industries.

The U.S. Coast Guard administers the federal and international safety framework for U.S. ports. The Coast Guard is a military service and branch of the U.S. armed forces, and Marine Safety is one of its 11 statutory missions. The Marine Safety mission and portions of the Marine Environmental Protection mission and Ports, Waterways, and Coastal Security mission are included in the Maritime Prevention mission program. The Coast Guard executes its Marine Safety mission by conducting flag state control (domestic) inspections, port state control (foreign) vessel exams, marine casualty (incident) investigations, ports and waterways management, merchant mariner credentialing, and regulations and standards development.1

This chapter begins with an introduction to the current international safety framework for gas carriers, as adopted by industry, government, and

___________________

1 Homeland Security Act of 2002, Sec. 888, “Preserving Coast Guard Mission Performance,” 107th Congress (2001–2002), https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/hr_5005_enr.pdf. Other missions include Search and Rescue, Drug Interdiction, Migrant Interdiction, Defense Readiness, Aids to Navigation, and Ice Operations. The 11 distinct missions are grouped into six major operational mission programs.

third-party organizations such as classification societies. It then explains the Coast Guard’s Port State Control (PSC) authority under international treaties and presents a history of the current Certificate of Compliance (COC) program for gas carriers, including the development of federal law and Coast Guard regulations and policy. Although the law behind the current COC program for foreign-flag gas carriers essentially has remained unchanged since 1978, this chapter examines how the international safety framework has greatly expanded since then. Coast Guard programs, such as the Liquefied Gas Carrier National Center of Expertise (LGC NCOE) and the Quality Shipping for the 21st Century (QUALSHIP 21) Initiative, were developed in support of safety as well.

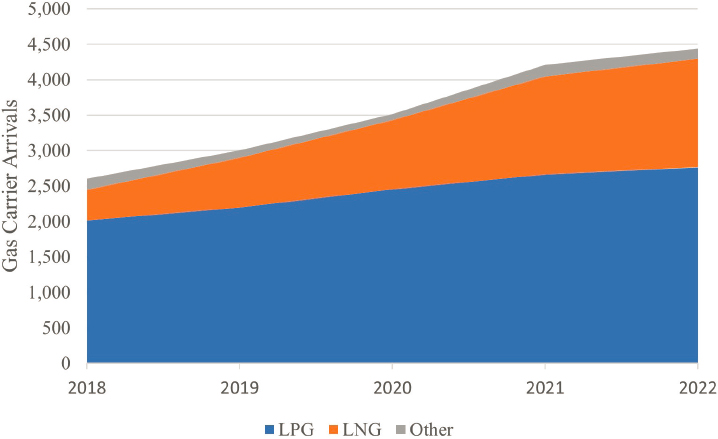

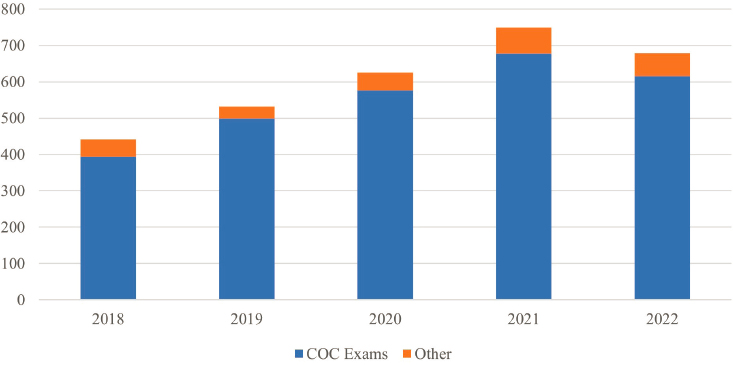

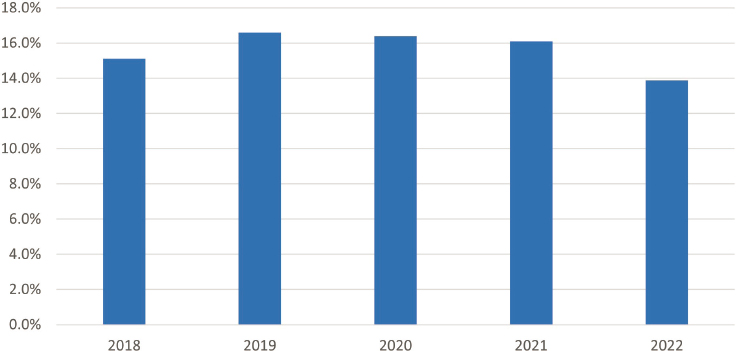

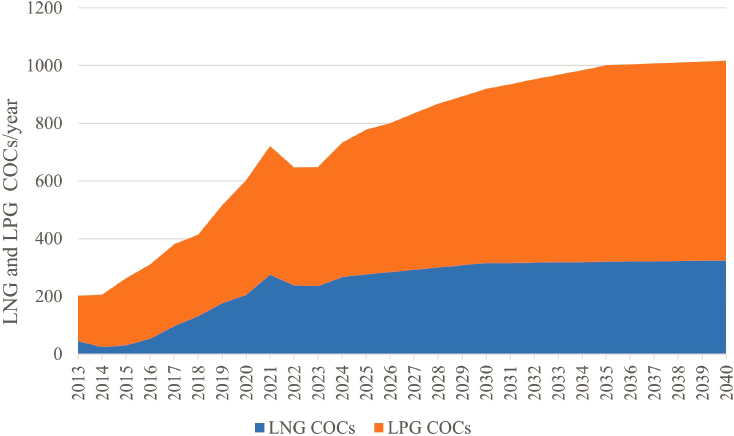

The chapter then moves to the current COC program’s impact on the Coast Guard. It presents a detailed description of the COC examination process and the impacts of the dramatic increases in gas carrier COC exams since 2010. It concludes with an examination of Coast Guard gas carrier examination data and their implications for safety, as well as a projection of future increases in COC exams and attendant impacts on the Coast Guard’s workforce if current federal law continues.

INTRODUCTION TO THE SAFETY FRAMEWORK FOR GAS CARRIERS

Regulation of commercial vessel safety was limited until the mid-19th century, when some nations began establishing regulatory bodies responsible for the safety of commercial vessels flying their flags. These bodies included the U.S. Steamboat Inspection Service, which was created in 1871 and traces its history back to the Steamboat Inspection Act of 1838, and the United Kingdom’s Board of Trade.2 At approximately the same time, private organizations known as classification societies were established to protect the commercial interests of cargo shippers. These organizations, including the American Bureau of Shipping (ABS) and Lloyd’s Register of Shipping, issued rules on the design, construction, and inspection of merchant vessels.3

Today multiple entities have different roles and responsibilities for ensuring the safe design and operation of any merchant ship. This framework is often referred to as a safety net. This section introduces the entities—including industry, government, and third-party organizations—involved

___________________

2 Barbara Voulgaris, “From Steamboat Inspection Service to U.S. Coast Guard: Marine Safety in the United States from 1838–1946,” 2009, https://media.defense.gov/2020/Apr/24/2002288416/-1/-1/0/2009_MARINE_SAFETY_HISTORY_VOULGARIS.PDF.

3 Harold M. Heiser, “Classification Societies,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 63, no. 408 (February 1937), https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1937/february/classification-societies.

in the safety net and responsible for ensuring the safety of gas carriers and their cargo.

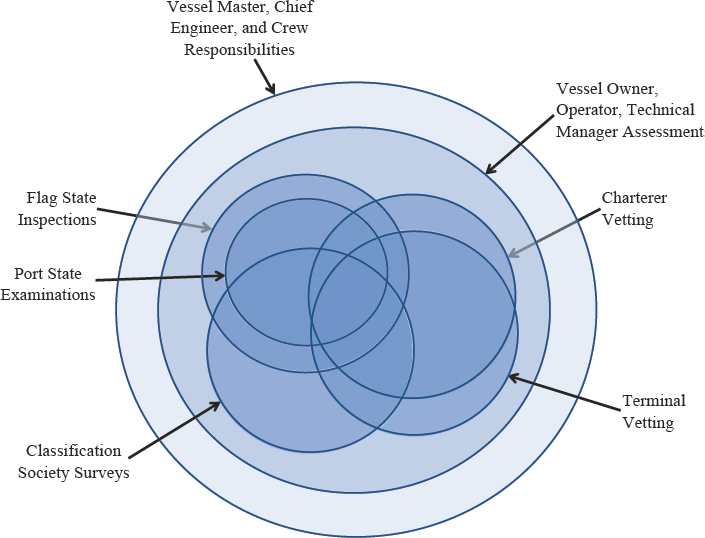

The safety net as it operates today for a gas carrier can be visualized as a series of overlapping circles: the actors in each circle have incentives and activities that support the overall safety of a vessel, its crew, and the surrounding port, terminals, and other vessels as well as the sea and shoreline environments. While governments and third-party organizations are responsible for enforcing the standards as represented in law, industry actors have financial incentives to pursue additional reliability and safety. While most of the actors view safety from the perspective of the vessel, terminals and the port state approach vessel safety from the perspective of the ports. The discussion below describes the responsibilities and incentives of each actor in Figure 3-1.

Industry

The safety of a gas carrier, as with any merchant vessel, begins with the vessel’s owner, master, and crew, who are ultimately responsible for ensuring

SOURCE: Committee analysis.

that the vessel is maintained in compliance with all applicable rules and regulations at all times. However, the structure of the U.S. export industries for LNG and LPG provides additional mechanisms and incentives for safety assurance. Reliability, of which safety is a significant part, is highly valued. Because the cargo is hazardous and there are potential liabilities and significant penalties if something goes wrong, the cargo owners and the insurers of the vessel and the cargo have financial incentives to ensure safety. Moreover, because the export industry is capital-intensive and debt-financed, downtime can be very expensive. The terminal facilities and the holders of the debt also have financial incentives to ensure that safety is maintained. In addition, the ocean shipping industry is segmented. Charterers, which may be the cargo owners or separate companies, contract for vessels for a defined length of time. Charterers have choices about which vessel owners and specific vessels they engage. A vessel, operator, or ship owner that is perceived as high risk is likely to find itself cut off from the U.S. LNG and LPG export markets. Further descriptions of the industry actors related to LGCs are described below.

Vessel Master, Chief Engineer, and Crew

As the most senior department heads on board the vessel, the vessel master and chief engineer are the most important and central actors in vessel safety. These two command personnel implement the safety system and programs aboard the ship. If they are not competent or motivated, the basic safety system fails. Ship owners/managers recognize this and put significant effort into the training, career progression, and promotion of individuals to these ranks. Industry and charterers also recognize the significance of a ship’s officers and have developed manning experience matrices to ensure that vessel owners/managers are putting people with proper training and experience aboard the ship. The master and chief engineer guide and direct the rest of the crew to ensure that the vessel is in compliance with all applicable rules and regulations. If a vessel is not in compliance with a charterer’s manning experience matrix, a ship may be put off-hire. In addition, many terminals have their own experience matrix, again to ensure that qualified and experienced personnel are operating ships. Charterers can also measure and audit the degree of compliance with their own experience matrices.

Vessel Owners, Operators, and Technical Managers

For the vessel master and chief engineer to do their jobs, they need to be given appropriate resources and support from the technical manager, who works for and receives and manages funding from the vessel owners and/or operators. The technical manager is the main person in charge of the safe,

efficient, and cost-effective performance of all ships assigned. The vessel owners and/or operators are responsible for providing enough resources to properly operate, maintain, and fully implement the safety management system (SMS), required by IMO’s International Safety Management Code (ISM Code), in the office and across the fleet. The SMS covers all aspects of vessel management including hiring, training, and promotion for vessel and shore personnel; technical support for the vessel (including development and implementation of a planned maintenance system covering all equipment on the vessel); operational support for the vessel (including compliance with all charter, terminal, and port requirements); development and implementation of health, safety, and environmental protection programs for the fleet; and overall compliance with statutory requirements (flag, class, IMO, etc.).

Charterers, Sub-charterers, and Commercial Managers

Charterers, sub-charterers, and commercial managers want to ensure that the ships that they hire are operated safely and reliably. A ship that is not operating safely will not be reliable. These stakeholders use vetting and assurance practices to determine if a specific gas carrier will be employed. Sub-charterers and commercial managers may have taken commercial positions on the loading and discharging of cargo, which can have an impact of tens of millions of dollars if not met for just one cargo. Therefore, sub-charterers and commercial managers will likely have their own vetting and assurance practices, on top of the charterer’s vetting practices, before taking on a ship. If a ship or manager becomes unacceptable to a charterer, it is a very serious financial issue for the vessel owner/operator/technical manager. Therefore, the owner/operator/technical manager generally assigns very high priority to resolving issues that arise during both internal inspections and charterer/terminal vetting, including ensuring that adequate resources are made available to fix any problem promptly and fully.

Terminals

Like charterers, terminals have a strong interest in ensuring that vessels calling at their facilities are safe and reliable. Terminals are also aware of their responsibilities to their other users and to the surrounding community. The most important issue is that the visiting vessel does not cause an incident that damages the terminal, restricting its future use. Therefore, terminals have their own vetting and assurance procedures that they typically engage every time a ship is scheduled to call. If a vessel has outstanding issues from previous vetting or terminal calls, a terminal may impose expensive countermeasures before loading/discharging and even refuse to allow the vessel access. An example is an unresolved issue with the propulsion machinery,

reducing the level of redundancy. The terminal may allow the vessel to load but only with a standby tug in attendance for the entire loading, potentially costing several tens of thousands of dollars.

Government

The United States is an active member of IMO, the United Nations’ specialized agency with responsibility for the safety and security of shipping and the prevention of marine and atmospheric pollution by ships. Founded in 1948 and coming into force in 1958, IMO develops standards that are adopted through international treaties for the safety, security, and environmental performance of international shipping. Currently, 175 IMO member nations meet regularly to develop and update international safety and environmental standards for commercial vessels. The oldest treaty under IMO’s administration is the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), which has its origins in the RMS Titanic disaster in 1912 and first came into force in 1933. Currently 168 nations are signatories to SOLAS. Today, SOLAS applies to approximately 99% of the world’s fleet, and it is generally regarded as the most important of all international treaties concerning the safety of merchant ships to include liquefied gas carriers.

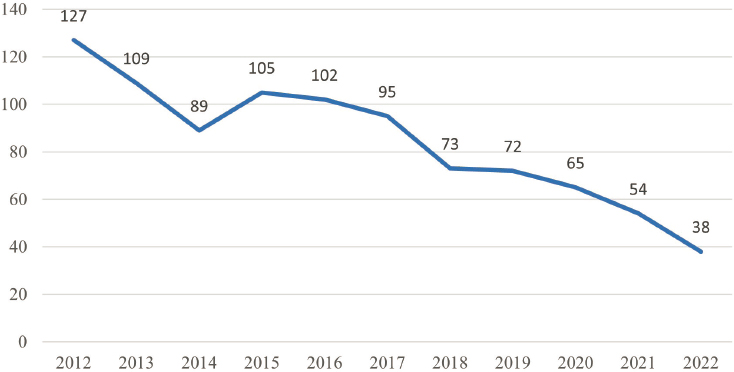

Additional key IMO standards relevant to gas carriers are in the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL), first adopted in 1973 and coming into force in 1983, and in the International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW), first adopted in 1978 and coming into force in 1984.4 The international conventions and industry standards are regularly updated. As demonstrated in Figure 3-2, improvements to SOLAS and other international standards have contributed to the reduction in the number of total vessel losses by almost 70% over the last decade.

Flag States

Under SOLAS and other international conventions, the government of the nation whose flag the ship is entitled to fly, commonly referred to as the flag state, is required to ensure that ships flying its flag comply with the standards established under international law and conventions.5

___________________

4 IMO, “Brief History of IMO,” accessed March 22, 2024, https://www.imo.org/en/About/HistoryOfIMO/Pages/Default.aspx.

5 SOLAS Regulation I/6, MARPOL Annex I Regulation 6, Annex II Regulation 8, Annex IV Regulation 4, Annex VI regulation 5, and United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea Article 94.

SOURCE: Data from Lloyd’s List Intelligence Casualty Statistics, https://lloydslist.com/sectors/casualty.

Flag registries, either directly or through the chosen recognized organization (RO), certify that the vessels are constructed, equipped, maintained, and manned to meet international standards. They also audit the management of the shipping company in which the technical manager resides to ensure that the vessel’s SMS is robust and that the technical manager is fulfilling the activities in the SMS. Flag requirements are also an important part of charterers’ or terminals’ vetting requirements.

Port State

SOLAS also authorizes the nation responsible for the ports to take actions to protect safety. When a foreign-flag gas carrier calls on a U.S. port, it is subject to PSC inspection, administered by the Coast Guard. SOLAS authorizes port states to verify that the certificates issued by the flag state are valid.6 Port states check a vessel and its equipment to confirm compliance with IMO standards and any additional port state requirements; this is to ensure that the vessel and equipment are manned and operated accordingly and maintain safety, security, and pollution prevention. While the port state is intended to provide assistance to flag state administrations in ensuring compliance with these standards and requirements, the port state role is completely independent of owners, class, and flag. The roles of the master,

___________________

6 SOLAS Regulation I/19.

crew, and owner are to keep the vessel operating safely, while the role of the port state is to keep the port operating safely. A port state inspection that finds many deficiencies—or worse, that leads to a detention that must be remedied before the vessel can leave the port—will require the owner to investigate and remedy safety issues to ensure that they do not recur. For the owner, vessel detention can mean revenue lost due to off-hire status and potential liabilities to the terminal and/or cargo owner for delays and other costs that impact their businesses.

Port states serve as the last entity in the “safety net” of the vessel. Gas carriers receive examinations from government agencies exercising PSC authority in ports all over the world. Many port states cooperate with each other to improve the efficiency of inspections and focus on the elimination of substandard ships. Nine regional agreements, or memoranda of understanding (MOUs), on PSC have been signed and cover many parts of the globe.7

Third-Party Organizations

Third-party organizations are of two types—the classification societies that provide independent confirmation that vessel standards have been met and the nongovernmental organizations that are collaborative mechanisms for industry to adopt and monitor best practices and standards that go beyond governmental requirements.

Classification Societies

Classification societies provide assurance to others in the maritime community—flag states, ports, vessel insurers, cargo insurers, etc.—that the vessel has been built and is being maintained according to international technical standards. Classification societies issue their own rules that are aligned with international standards and employ “surveyors” who review the vessel’s design drawings, attend during construction, and regularly conduct surveys and inspections over the life of the vessel in accordance with the society’s own rules and standards. Technically, a classification society’s rules are not mandatory; however, meeting these class requirements positively impacts insurance premiums, thereby encouraging voluntary compliance. Keeping a vessel in compliance with classification requirements (i.e., “in class”) is a fundamental part of charter contracts and other commercial agreements.

The International Association of Classification Societies sets out uniform standards for its 12-member classification societies to uphold in their

___________________

7 See https://www.imo.org/en/ourwork/msas/pages/portstatecontrol.aspx.

periodic vessel inspection work.8 Classification societies are also embedded in IMO and flag state requirements. SOLAS requires gas carriers and other vessels to be designed, constructed, and maintained in compliance with the structural, mechanical, and electrical requirements of a classification ociety recognized by the flag state.9 In addition, flag states typically entrust classification societies to act on their behalf. Classification societies serving as IMO ROs are empowered to conduct inspections and surveys of gas carriers, require repairs, and ensure compliance. As the RO on behalf of the flag state, the classification society will issue SOLAS and other certificates to gas carriers that comply with the relevant international standards. Because classification societies audit and advise technical managers on keeping a vessel “in class” and in compliance with international standards, their role in the safety net is to enforce threshold standards.

Nongovernmental Organizations

Industry also organized third-party organizations in response to growing public concern about marine pollution, in particular oil pollution, in the late 1960s. The Oil Companies International Marine Forum (OCIMF), founded in 1970, and the Society of International Gas Tanker and Terminal Operators (SIGTTO), founded in 1979, are voluntary organizations that promote safety and environmental protection within their respective industries. Today, OCIMF has 111 member companies, and SIGTTO has 170 member companies. Both produce guidelines and tools used by industry and are seen as leading authorities on the global marine industry’s safety and environmental performance. As they are nongovernmental organizations, IMO has granted OCIMF consultancy/advisory status and SIGTTO observer status.10

THE COAST GUARD AND PORT STATE CONTROL

PSC is the process by which the United States and other nations exercise authority over foreign vessels in waters subject to their jurisdiction. The goal of the Coast Guard’s PSC program is to eliminate substandard ships from U.S. waters. Ships that do not meet the standards mandated by applicable international treaties and U.S. laws and regulations could endanger the ship and persons on board or create undesirable consequences for the marine environment. The United States has a robust PSC program and conducted more than 8,700 foreign vessel examinations in 2022.

___________________

8 For a list of members, see https://iacs.org.uk.

9 SOLAS Regulation II-1/3-1.

10 OCIMF, “About OCIMF,” accessed March 22, 2024, https://www.ocimf.org/about-ocimf; SIGTTO, “About Us,” accessed March 22, 2024, https://www.sigtto.org/about-us.

The Coast Guard’s authority to conduct inspections on board vessels and to certify compliance with government standards originates in the federal government’s response to the new dangers posed by steamboat transport and a series of laws enacted in the mid-19th century, culminating in the centralization of the Steamboat Inspection Service in the U.S. Department of the Treasury in 1871. The inspection service was transferred to the Coast Guard in 1942 as part of consolidating all responsibilities for marine safety, including vessel inspections, in one federal agency.11

The Coast Guard’s authority to inspect vessels was based on declarations of a national emergency or for national security until the Ports and Waterways Safety Act of 1972. This law formally established the captain of the port (COTP) with the authority to regulate the operation of domestic and foreign ships on the navigable waters of the United States. Today, almost all U.S. and foreign-flag vessels operating in U.S. waters are subject to Coast Guard inspection under Title 46 U.S. Code (USC) Chapter 33.

In addition, nations that are party to SOLAS and certain other international conventions may verify that vessels of other nations operating within their waters comply with the conventions and may take action to bring ships into compliance if they are deficient. A nation may also enact its own laws and regulations to impose additional requirements on foreign vessels trading in its waters. Reciprocity is accorded to vessels flagged with countries that are parties to SOLAS.12 In other words, foreign nations that are signatories to SOLAS are assumed to have inspection laws and standards that are similar to those in the United States. When a flag state, or its designated RO, determines that a vessel meets specified standards, the government issues the vessel a certificate signifying compliance.

The Coast Guard verifies that foreign-flag vessels operating in U.S. waters comply with applicable international conventions, U.S. laws, and U.S. regulations through the use of PSC examinations. Under 33 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 1.01-12(a), the officer in charge, marine inspection (OCMI), who is generally the same individual as the COTP, is responsible for SOLAS intervention on foreign-flag ships. When the Coast Guard identifies a vessel that is not in substantial compliance with applicable laws or regulations, it imposes a detention or other controls to limit movement or operations of the vessel until the substandard conditions have been rectified and the vessel is brought into compliance.

___________________

11 This paragraph relies on information from Barbara Voulgaris, “From Steamboat Inspection Service to U.S. Coast Guard: Marine Safety in the United States from 1838–1946,” 2009, https://media.defense.gov/2020/Apr/24/2002288416/-1/-1/0/2009_MARINE_SAFETY_HISTORY_VOULGARIS.PDF. See also National Archives, “Acts of Congress Relating to Steamboats, Collated with the Rolls at Washington,” https://archive.org/details/aft7919.0001.001.umich.edu/page/n3/mode/2up.

12 46 USC § 3303 – Reciprocity for foreign vessels.

PSC examinations help to confirm that a vessel’s major systems comply with applicable international standards and U.S. requirements and that the crew possesses proficiency sufficient to safely operate the vessel. Through the PSC exam, the Coast Guard determines whether the required certificates are on board and valid, and whether the vessel conforms to the conditions required for issuance of the certificates. This is accomplished by a walk-through examination and visual assessment of a vessel’s relevant components and documents, as well as limited testing of the vessel’s systems and crew. PSC exams are not intended, nor desired, to be as rigorous as Coast Guard inspections for certification of U.S. flag vessels.13

With approximately 11,000 different foreign-flag ships typically making nearly 80,000 port calls to the United States each year, it is neither possible nor necessary for the Coast Guard to examine each vessel at every port call. The Coast Guard uses a risk-based decision tool to identify and manage the risk posed by arriving vessels. The risk-based approach, which uses targeting procedures,14 has proven to be effective, resulting in a decrease in the number of substandard vessels and an improvement in the performance of classification societies and flag states.

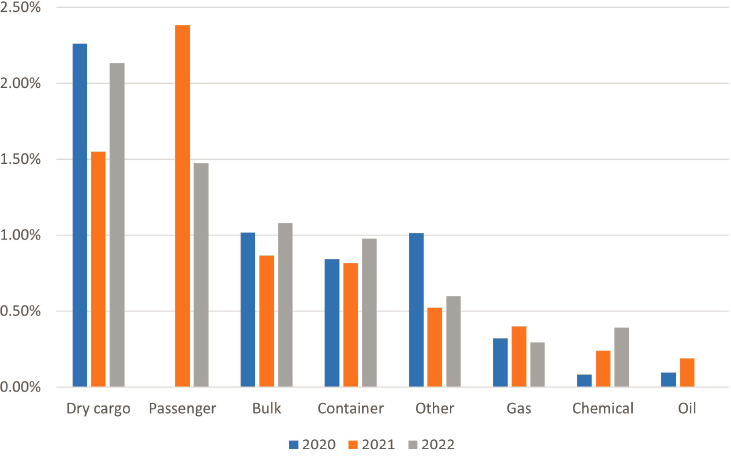

Today, substandard vessels are less likely to call on U.S. ports. Over the past decade, more than 70% of PSC exams conducted by the Coast Guard resulted in no deficiencies issued to the vessels.15 Detention ratios steadily decreased from a high of nearly 8% in the late 1990s to approximately 1% by 2006, where they have remained since.16

U.S. REQUIREMENTS FOR GAS CARRIERS

In addition to being subject to international standards, foreign gas carriers visiting U.S. ports are subject to U.S. standards, as contained in U.S. law and Coast Guard regulations and policy, including the requirement for a COC. This section delves into the history of the U.S. laws that led to the Coast Guard’s COC program and related regulations and policies. Although gas carrier technologies and standards have changed, U.S. law for foreign-flag gas carriers has remained the same since 1978. Box 3-1 contains a summary of current U.S. law and Coast Guard regulations and policies that pertain to this report’s discussion of the COC program for foreign gas carriers.

___________________

13 COMDTINST 16000.73, Marine Safety: Port State Control (D1-12), September 2021.

14 COMDTINST 16000.73, Marine Safety: Port State Control (D4), September 2021. See https://media.defense.gov/2022/Feb/09/2002935707/-1/-1/0/CI_16000_73.PDF.

15 Port State Control Division, PSC Annual Reports.

16 See PSC Annual Reports. See also Coast Guard CVC Work Instruction, “Targeting of Vessels for PSC Examination,” January 13, 2020, https://www.dco.uscg.mil/Portals/9/DCO%20Documents/5p/CG-5PC/CG-CVC/CVC_MMS/CVC-WI-021.pdf.

BOX 3-1

Summary of U.S. Law, Regulations, and Policies Pertaining to Certificates of Compliance for Foreign Gas Carriers

Title 46 U.S. Code (USC) Chapter 37 Carriage of Liquid Bulk Dangerous Cargoes

46 USC 3703 Regulations

- Authorizes the Coast Guard to regulate gas carrier design, construction, maintenance, and operation; see 46 CFR 154 below.

46 USC 3710 Evidence of Compliance by Vessels of the United States

- Requires U.S.-flagged vessels authorized to carry oil or hazardous material in bulk (including liquified or compressed gas) to hold a Certificate of Inspection (COI) with an endorsement indicating the vessel meets applicable requirements.

- Each COI is valid for not more than 5 years.

- A COI may be suspended or revoked.

46 USC 3711 Evidence of Compliance by Foreign Vessels

- Requires a Certificate of Compliance (COC) with U.S. law and regulations before a foreign-flag vessel may operate in the navigable waters of or conduct cargo operations in the United States.

- Each COC is valid for not more than 24 months.

- A COC may be suspended or revoked.

46 USC 3714 Inspection and Examination

- Each vessel must be inspected (U.S. flag) or examined (foreign flag) at least once each year.

- Each vessel more than 10 years of age must undergo an inspection of structural strength and hull integrity.

- An inspector may be contracted to conduct inspections or examinations and issue temporary certificates.

Coast Guard Regulations

46 CFR 154, Safety Standards for Self-Propelled Vessels Carrying Bulk Liquefied Gases, Also part of 46 CFR, Subchapter O

- Includes design requirements that exceed IMO’s International Code for the Construction and Equipment of Ships Carrying Liquefied Gases in Bulk.

- Implements the COC initial issuance, renewal, and annual examination requirements.

Coast Guard Policies

COMDTINST 16000.73, Marine Safety: Port State Control (D6-5), September 2021

- Allows cargo operations if the vessel is not more than 3 months beyond the expiration date of the previous COC renewal or the anniversary date of the previous COC exam; the required exam/renewal must be completed prior to departing.

- Requires vessels more than 3 months beyond the expiration date of their COC renewal or anniversary date of the previous COC exam to complete the examination process before commencing cargo operations.

U.S. Law

The COC program in operation today was developed under two federal laws: the Ports and Waterways Safety Act of 1972 and the Port and Tanker Safety Act of 1978. The 1972 act, as previously mentioned, gave the Coast Guard permanent jurisdiction over all vessels using ports of the United States. It also addressed the safety of ports and waterfront facilities, as well as environmental protection of U.S. waters.17 The 1978 act was a culmination of governmental actions to address tank vessels that date back to the Tank Vessel Act of 1936.

Tank vessels began moving oil in substantial quantities after World War I, but prior to 1936, tank vessels remained comparatively unregulated until a series of events in the 1930s drew attention to problems associated with these types of vessels. To start, oil began replacing coal for home heating purposes, which increased the number of shipments between the U.S. Gulf Coast and East Coast and imports from Venezuela. At the same time, concerns for maritime safety were growing worldwide, which were linked to the Convention for Promoting Safety of Life at Sea, 1929. The U.S. Tank Vessel Act of 1936 established the federal authority to regulate tank vessels carrying flammable or combustible liquid cargo in bulk. The law required tank vessels to undergo an inspection and hold a Certificate of Inspection (COI) with a cargo endorsement indicating what it was approved to carry, prior to taking on cargo. These requirements applied to domestic and foreign vessels; however, there was an automatic exemption for a foreign vessel holding a valid COI from another country recognized under law or treaty.18

The authority to regulate tank vessels remained essentially the same until the Ports and Waterways Safety Act of 1972.19 In the 1972 law’s statement of policy, Congress declared that vessels carrying certain cargo in bulk created substantial hazards, that existing standards needed to be improved, and that it was necessary to establish comprehensive standards. The law expanded to apply to all vessels carrying oil of any kind in bulk and to vessels carrying hazardous polluting substances in bulk.

In addition, the 1972 act established the COC to ensure that foreign-flag tank vessels complied with U.S. marine environmental protection rules and regulations. Certificates would be valid for a period specified by the secretary but were not to exceed the duration of the COI.20 The 1972 law stated that the secretary may accept foreign certificates, but it did not

___________________

17 H.R. Rep. No. 95-1384, 95th Congress, 2nd Sess. 27 (1978), https://www.congress.gov/bill/95th-congress/house-bill/13311/summary/19?s=1&r=2.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 46 USC 391a (1976) – Shipping.

require acceptance. This meant that any foreign vessel could be examined to assure compliance with U.S. requirements.21

In December 1976, the foreign-flag tank vessel Argo Merchant grounded near Nantucket Island and released 204,000 barrels of heating oil into the water. That same month, the foreign-flag tank vessel Sansinena exploded and burned at a terminal in Los Angeles. Eight people lost their lives, 50 others were injured, and there was considerable shoreside damage and harbor pollution. In addition, there was a massive increase in U.S. oil imports, particularly crude oil. By 1978, the United States was importing more than 8 million barrels of crude oil per day, which was more than one-quarter of the crude oil moving in worldwide trade. Approximately 35 tank vessels were entering U.S. ports each day. The U.S. Department of Energy was also preparing to implement the Strategic Petroleum Reserve program, which was going to involve additional crude oil imports. Members of Congress became concerned that maritime traffic in U.S. ports continued to increase, marine incidents including fatalities continued to occur, and the marine environment was increasingly damaged by pollution. The result was the Port and Tanker Safety Act of 1978.22

The 1978 act emphasized safety as well as environmental protection. Its statement of policy declared that existing standards needed to be more stringent and comprehensive for the mitigation of hazards to life, property, and the marine environment. The statement also determined that existing international standards were incomplete, that those international standards were often left unenforced by some flag states, and that there was a need to prevent substandard vessels from operating in the navigable waters of the United States.23

The 1978 act separated the regulation and inspection of domestic and foreign vessels. While earlier law stated that a certificate shall not be issued until the vessel had been inspected,24 the 1978 act left this language for U.S. flag vessels but created a separate paragraph for foreign vessels that stated that a COC shall not be issued until the vessel had been examined.25 This distinction between inspection and examination would affect the Coast Guard’s implementation of the law. Certificates issued under the 1978 act were valid for a period not to exceed 24 months.26

The 1978 act also created a periodic inspection program, in addition to the certificate program, for both domestic and foreign tank vessels. The periodic inspection program required each domestic vessel to be inspected

___________________

21 H.R. Rep. No. 98-338. 111th Congress, 1st Session (1983).

22 H.R. Rep. No. 95-1384. 95th Congress, 2nd Sess. 27 (1978).

23 46 USC 391a (1982) – Shipping.

24 46 USC 391a (1976) – Shipping.

25 46 USC 391a (1982) – Shipping.

26 Ibid.

and each foreign vessel to be examined at least once each year.27 The law allowed the annual inspection or examination to be conducted by any officer authorized by the secretary. It also stated that if an officer was not reasonably available, the secretary may contract for the conduct of inspections or examinations.28 At the time, the primary reason for allowing contracting was to provide hiring flexibility in foreign areas where qualified Coast Guard marine inspectors were not normally available. However, it was recognized that on occasion, Coast Guard marine inspectors might not be readily available in the United States and that it might be necessary to contract services to facilitate and expedite inspections and examinations.29

In 1996, the law was amended to increase the length of time that certificates issued to U.S. tank vessels were valid from 24 months to 5 years. The purpose of the change was to align the U.S. certificate renewal intervals with those found in SOLAS and with ABS’s practices for its special periodic surveys. Congress did not envision any decrease in the level of safety due to these changes, because vessels on 5-year certificate renewal cycles would continue to receive annual inspections to ensure they complied with their COI. The certificate renewal interval for the COC for a foreign vessel was not changed and remained at 24 months.30

In summary, 46 USC 3714 requires all gas carriers to be examined at least once per year. 46 USC 3710 requires a domestic gas carrier to hold a COI prior to having cargo on board. These COIs are valid for 5 years. 46 USC 3711 requires any foreign-flag tankship, including a gas carrier, to hold a COC before the vessel may operate on the navigable waters of the United States or transfer cargo in a port or place under the jurisdiction of the United States. In addition, it restricts the term of the COC to not more than 2 years.

Finally, the COC program is unique to the United States. The committee did not identify any other countries that exercise PSC authority in the same manner as the United States or restrict foreign-flag gas carriers from operating unless they have been issued a COC or similar port state documentation.

U.S. Regulations

U.S. regulations further implement the COC requirements for gas carriers found in federal law.31 The regulations for gas carrier examinations and

___________________

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 H.R. Rep. No. 95-1384. 95th Congress, 2nd Sess. 27 (1978).

30 H.R. Rep. No. 104-106. The House Report does not discuss why the certificate renewal interval for foreign vessels was not changed.

31 In addition, federal regulations require foreign-flag cruise ships and mobile offshore drilling units to have a COC to operate in the United States; see 46 CFR 2.01-6.

COCs are found in Title 46 CFR Subchapter O, Part 154. 46 CFR 154.150 states that a vessel must call at a U.S. port for an examination before the vessel can receive a COC.

During the late 1960s, as LPG exports increased from U.S. Gulf ports and large imports of LNG appeared necessary in the near future, the federal government grew concerned that there was no international safety standard for the design of gas carriers under SOLAS. However, the Coast Guard had domestic regulations for the transportation of liquid flammable gases, contained in 46 CFR Subchapter D, Part 38, which were based on standards developed by the American Petroleum Institute and applied to the design of inland barges transporting liquefied flammable gas. To address this regulatory gap in SOLAS for the design of LNG and LPG ships, the Coast Guard prepared “Interim Guidelines for the Plan Review of Liquefied Flammable Gas Carriers” based upon existing domestic regulations. Foreign gas carriers were required to submit plans for their gas cargo systems to Coast Guard headquarters for review. Upon completion of the plan review and at the first call in a U.S. port, the OCMI (assisted by headquarters personnel, if requested) conducted an inspection to confirm that the gas cargo systems corresponded to the approved plans. At that point, the Coast Guard issued a letter of compliance (LOC) to the ship. Ongoing inspections were not required because the LOC’s purpose was to confirm that the ship had been constructed in accordance with approved plans.

In 1975, under U.S. leadership, IMO adopted the Code for the Construction and Equipment of Ships Carrying Liquefied Gases in Bulk” (GC Code), which provided a SOLAS standard for gas carrier design.32 In 1983, IMO adopted an updated set of requirements for gas carriers called the International Code for the Construction and Equipment of Ships Carrying Liquefied Gases in Bulk (IGC Code).33 The IGC Code became mandatory under SOLAS on July 1, 1986. Although the LOC program is no longer necessary, Coast Guard regulations still require the submission of ship plans, under 46 CFR 154.22, to receive what is called a Subchapter O endorsement (SOE) that verifies that the vessel meets design requirements. Unlike for most types of foreign vessels entering U.S. ports, U.S. standards for gas carriers do not simply mirror international design and construction requirements. Using the regulatory process, the Coast Guard has established four regulations that are more stringent than the IGC Code.34

___________________

32 RESOLUTION A.328(IX) adopted on 12 November 1975, Code for The Construction and Equipment of Ships Carrying Liquefied Gases in Bulk. https://wwwcdn.imo.org/local-resources/en/KnowledgeCentre/IndexofIMOResolutions/AssemblyDocuments/A.328(9).pdf.

33 Resolution MSC.5(48), adopted 1983, The International Code for the Construction and Equipment of Ships Carrying Liquefied Gases in Bulk, https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Safety/Pages/IGC-Code.aspx.

34 Coast Guard Proceedings 72, no. 3 (Fall 2015).

First, the United States requires enhanced grades of steel along the cargo area of a gas carrier’s hull to arrest cracks in the event of a cargo spill.

Second, the United States prohibits venting cargo vapor into the atmosphere at all ports, a practice that was allowed for temperature/pressure control under previous versions (prior to 2016) of the IGC Code, but is no longer allowed for vessels built since 2016. Because of this prohibition, the United States requires that foreign vessels maintain cargo tank pressure below the design vapor pressure either indefinitely or for a period of not less than 21 days for LNG.

Third, the United States sets different maximum allowable relief valve (MARV) settings for gas carriers using independent Type B and C tanks. The United States uses more conservative (higher) stress factors, which results in lower permissible pressure settings. Therefore, foreign-flag gas carriers are typically approved for two MARV settings: one for operating in international waters and one for U.S. waters. Prior to entering U.S. waters, the foreign vessel crew must set tank relief valves to the lower approved U.S. MARV settings. Because of advancements in construction materials, manufacturing, and inspection since the regulations were developed, the United States now accepts the international MARV settings for independent Type B and C tanks on vessels that were built to the standards found in the 1993 edition of the IGC Code or later. For gas carriers using membrane, semi-membrane, and independent Type A tanks, the allowable stresses in the tank are the same in the IGC Code and U.S. regulations.

Fourth, the United States uses more extreme ambient design temperatures for vessels required to have secondary barriers. To evaluate the insulation and hull steel for cargo tanks and secondary barriers for the purpose of design calculations, the IGC Code provides general standards and allows each flag state to dictate a higher or lower ambient minimum design temperature. The IGC Code’s general ambient design temperatures are 41°F for still air and 32°F for sea water. The United States specifies additional ambient design temperatures for vessels required to have a secondary barrier. The temperatures are 0°F for 5 knots air and 32°F for still sea water for any waters in the world, except Alaskan waters. For Alaskan waters, the temperatures are –20°F for 5 knots air and 28°F for still sea water.35

Coast Guard Policy

The Coast Guard conducts safety and environmental protection compliance exams and security exams on board foreign-flag vessels under the PSC

___________________

35 Ibid.

program. Though these exams are different, they are typically completed at the same time.36

Per the targeting procedure in Coast Guard policy, the COC is considered a PSC exam; however, the two are technically separate from a regulatory and programmatic perspective.37 COC exams are conducted by qualified Port State Control officers (PSCOs) and Port State Control examiners (PSCEs) with specific qualifications for certain cargos such as oil, chemical, and gas.

For the COC program, Coast Guard policy permits OCMIs and COTPs to allow gas carriers to commence cargo operations if there are no indications that the vessel is out of compliance and if the vessel is not more than 3 months beyond the expiration date of its COC renewal or, if due for an annual exam, is not more than 3 months beyond the anniversary date of the COC. In these cases, the required exam must be completed prior to the vessel departing. Vessels that are more than 3 months beyond the expiration date of their COC renewal or annual exam must have the required exam prior to commencing cargo operations.38

Coast Guard policy contains procedures for conducting COC exams overseas, but the policy is limited to tank vessels that conduct lightering operations39 inside the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone and therefore do not come into port or come close enough to a U.S. port to allow the Coast Guard easy access from shore. Prohibiting offshore examinations minimizes risk to Coast Guard personnel that would otherwise have to fly offshore and reduces already short marine inspector workforce efficiency due to the time and limitations of traveling offshore.40

EXPANSION OF SAFETY ASSURANCE PROGRAMS

Congress enacted the Ports and Waterways Safety Act of 1972 and the Port and Tanker Safety Act of 1978 because it had concluded not only that existing standards for all types of cargo ships and tankers were incomplete but also that some flag states were leaving standards unenforced. At that time, the COC program was a mechanism to prevent vessels that did not meet the needed comprehensive standards from operating in the navigable waters of the United States. Since 1978, the international conventions that

___________________

36 COMDTINST 16000.73, Marine Safety: Port State Control (D1-8), September 2021.

37 COMDTINST 16000.73, Marine Safety: Port State Control (D6-1), September 2021.

38 COMDTINST 16000.73, Marine Safety: Port State Control (D6-5), September 2021.

39 “Lightering operations” means “the transferring of cargoes at sea from large deep-draft vessels to shallow-draft vessels for subsequent transfer to shoreside terminals due to the inability of the larger tank vessels to enter shallow ports.” See 46 USC 3715.

40 COMDTINST 16000.73, Marine Safety: Port State Control (D6-34), September 2021.

set standards for gas carriers have become more comprehensive. In addition, the gas carrier industries have expanded their own safety assurance programs.

This section highlights the significant changes to the gas carrier industry since 1978 and demonstrates that today’s safety net for gas carriers is much larger and more comprehensive, with multiple overlapping layers to ensure that these vessels comply with marine safety and environmental protection rules and regulations.

International Standards

Gas carriers calling at U.S. ports must meet international standards for safety, pollution prevention and response, and workers. SOLAS requires gas carriers with a keel laid date of July 1, 1986, or later to meet the IGC Code, which prescribes the international design and construction standards for the safe carriage of liquefied gases.41 SOLAS also requires gas carriers to be designed, constructed, and maintained in compliance with the requirements of a classification society.42 IMO recognizes that gas carrier design technology is a complex and rapidly evolving technology, and that the IGC Code should not remain static. Therefore, the IGC Code is kept under review, facilitating the integration of experience and technological developments. The IGC Code has been amended 13 times, most recently in 2022, in order to make improvements and to account for new technologies. The IGC Code applies to ships engaged in the carriage of liquefied gases, regardless of their size, including those of less than 500 gross register tons (GRT).43

The ISM Code was adopted by IMO in 1993 and entered into force on July 1, 1998. The ISM Code is mandatory under SOLAS, Chapter IX. The ISM Code takes a different approach to ship safety, by focusing on the operator’s management system rather than the physical condition of the vessel. The concept is that the managers are responsible for ensuring the quality of the vessels within their fleets. The three main principles of the ISM Code are to (1) promote safe practices in ship operations and working environments, (2) identify and mitigate risks, and (3) continuously enhance safety management skills of onboard and ashore personnel. The ISM Code is mandatory for passenger and cargo ships (including gas carriers) of 500 GRT and upward that are engaged in international voyages.

___________________

41 SOLAS Chapter VII, Regulation 13.

42 SOLAS Chapter II-1, Regulation 3-1.

43 The Code for the Construction Equipment of Ships Carrying Liquefied Gases in Bulk (IGC Code) and the Code for Existing Ships Carrying Liquefied Gases in Bulk (EGC Code), which were adopted by IMO on November 12, 1975, and entered into force on October 31, 1976, cover older ships.

In addition, MARPOL provides standards to prevent pollution of the marine environment and atmosphere by gas carriers. Additional MARPOL protocols were adopted in 1978 and 1997, and the convention has been updated by several amendments over the years. STCW establishes standards for seafarers that operate gas carriers that trade internationally and call on U.S. ports. Other international treaties cover various aspects of international shipping.

Enforcement of International Standards

Under SOLAS, Chapter I, Regulation 6, enforcement of the regulations in the convention is left to the SOLAS flag state whose flag the ship is entitled to fly. These inspections for SOLAS compliance consist of plan review and surveys during construction of the ship, which are followed by a series of periodic surveys throughout the ship’s life. Compliance is documented by the issuance of or endorsement on the applicable IMO certificate that indicates the satisfactory completion of the relevant survey. If a ship is found to be out of compliance or unsafe to proceed to sea due to an accident or defect discovered, the flag state must be notified to determine if an additional survey is required. If the ship is in a port of another contracting state to the SOLAS convention (port state), the appropriate authorities of the port state must also be notified.

For cargo ships, surveys take place on a 5-year cycle under SOLAS, Chapter I, Regulations 8, 9, and 10. The renewal survey takes place 5 years after initial full-term certificates are issued. Upon successful completion of the renewal survey, a new certificate is issued by the flag state. The renewal survey consists of a complete inspection to verify compliance with SOLAS and is similar to but not as extensive as a survey required for new construction. A periodic or intermediate survey is required approximately 30 months after the original certificate is issued. This intermediate survey is less extensive and intended to verify that the ship remains in compliance. Finally, three annual surveys are required: these are less detailed general inspections of the ship’s condition. With planning, the intermediate survey can also serve as the second or third annual survey. Deficiencies noted during the surveys must be corrected.

In the case of a U.S. flag cargo ship, the Coast Guard issues a COI. The COI is valid for 5 years under 46 CFR 31.01. This is in addition to SOLAS certificates issued to U.S. flag ships engaged in international voyages. Prior to February 2000, the COI issued to U.S. cargo ships was valid for 2 years; however, the Coast Guard Authorization Act of 1996 amended 46 USC 3307 to permit 5-year validity for the purpose of harmonizing inspections with IMO requirements.

Under SOLAS, Chapter I, Regulation 19, port states have the authority to verify that ships from other administrations are in compliance with SOLAS as evidenced by their valid certificates. If the certificate has expired or the vessel is not in substantial compliance, the port state may detain the ship, preventing it from sailing until the deficiencies are corrected. In the case of a port state detention, the ship’s administration and IMO must be notified.

Coordination Among PSC Programs

To exercise their authority to examine foreign vessels operating in their waters and ensure that they comply with international requirements, many nations have developed PSC programs similar to the Coast Guard’s program. This means that some ships may receive multiple redundant PSC examinations per year. On the other hand, some countries do not have the resources to examine every foreign ship. For these reasons, many countries work together to share PSC information and results through formalized MOUs.

PSC MOUs reduce the number of unnecessary examinations for individual ships, while helping focus PSC efforts on substandard ships. The first such agreement, the Paris MOU, covers Europe and Canada and was implemented in 1982. In 1991, IMO adopted a resolution encouraging regional PSC cooperation in other parts of the world. Today, there are nine MOUs around the world. According to the 2022 Paris MOU Annual Report, the 27 nations of the Paris MOU conducted 17,908 PSC examinations, found 47,167 deficiencies during these exams, and detained 723 vessels. The vessels examined in 2022 included 587 gas carriers, 6 of which were detained.44

The Tokyo PSC MOU, which took effect in 1994, covers the Asia–Pacific region and is made up of 21 nations. According to the 2022 Tokyo MOU Annual Report, these countries conducted 24,894 examinations on 15,853 individual ships, resulting in 46,769 deficiencies and 725 vessel detentions. The vessels examined in 2022 included 524 gas carriers, 8 of which were detained.45

Industry Collaboration and Vessel Vetting

Although maritime transport is a relatively safe mode of transportation, there are still accidents; whenever these occur, there are usually significant personal, economic, and environmental costs. As a result, companies that

___________________

44 See https://parismou.org/system/files/2023-06/Paris%20MOU%20Annual%20Report%202022.pdf.

charter a vessel to carry their cargo will generally conduct a vetting process to evaluate whether the vessel complies with international regulations and industry standards and to determine that the vessel is suitable to carry their cargo safely. A vetting inspection provides a thorough evaluation of the ship, along with its procedures and equipment. When the oil industry began vetting ships in the 1970s, each company had its own staff to conduct vetting. Today, vetting can be conducted by the charterer, the loading or receiving shore-terminal staff, or third-party companies that specialize in conducting such vetting inspections. They tend to follow an industry-developed ship inspection format. Although ship vetting inspection is not mandatory under international law, it is often required in the contract between charter parties and has therefore become a commercial necessity. A charterer will usually have options when it comes to selecting a ship, so the ship owners must accept the vetting process if they want to carry the cargo. Most gas carriers are subject to a vetting process.46

As part of promoting best practices in the design, construction, and operation of vessels transporting liquefied gas, crude oil, oil products, and petrochemicals, OCIMF provides an independent forum for bringing together its members and external stakeholders. OCIMF has produced a portfolio of guidance publications, tools, and inspection programs used by thousands of vessel owners, operators, managers, and charterers worldwide to enhance the safety and environmental performance of their operations. These include the Ship Inspection Report (SIRE) program, the Tanker Management and Self-Assessment (TMSA) program, and the Condition Assessment Program (CAP).

SIRE Program

In addition to the flag state inspections and classification society surveys, gas carriers are also subject to inspection under the SIRE program, which was introduced by OCIMF in 1993.47 Unlike classification society surveyors, who ensure compliance with the required standards, SIRE inspectors examine gas carriers and apply additional standards that are typically more stringent or focus on other areas. A SIRE inspection does not result in issuance of any mandatory regulatory certificates or documents. Instead, a SIRE inspection collects objective technical and operational data that are retained in a large database containing information shared by OCIMF members on all gas carriers. SIRE information informs vessel vetting processes in advance of chartering decisions and helps drive improvements in vessel quality and

___________________

46 See also Juan P. Presedo, Ship Vetting and Its Application to LNG, 3rd Edition (Witherbys, 2023).

47 See https://www.ocimf.org/document-libary/71-programmes-sire/file.

safety. By establishing a standardized, objective inspection process that systematically examines tanker operations, SIRE has been instrumental in driving up charterer expectations for operational behavior and safety standards in the industry. OCIMF is currently phasing in a revised SIRE 2.0, which, among other updates, will complete the digitization of inspection data. This will allow the more efficient analysis of aggregate data to spot trends across fleets and of granular data to identify root causes and evaluate mitigation.48

SIRE inspections are completed by accredited inspectors who follow a set of defined inspection criteria. Generally, these inspections take at least 8–12 hours. At the end of the inspection, any deficiencies are noted in a SIRE inspection report, along with the reason for the deficiency, a plan to rectify the problem, and steps to prevent reoccurrence. The inspection reports are then entered into a dedicated database hosted by OCIMF. This process produces a very large database of up-to-date information about tankers and barges, including gas carriers. Prospective charterers and other industry members can access the database and use the technical and operational information to ascertain whether a vessel is well maintained and managed. Since SIRE’s introduction, more than 180,000 inspection reports have been submitted. On average, industry representatives view more than 8,000 SIRE reports each month. Although a SIRE report is valid for 12 months, charter parties often state that a vessel must have a satisfactory report in the SIRE system that is not more than 6 months old. In practice, this often means charterers require the vessel to undergo a SIRE inspection at least every 5 months. Some charterers or terminals also require SIRE reports from a specific inspection company, which can mean that a vessel may undergo several SIRE inspections each year.49

TMSA Program

OCIMF introduced the TMSA program, designed to be used by the vessel or terminal managers, in 2004. This program provides companies with a method to improve and measure their own SMS. It encourages companies to assess their SMS against key performance indicators and provides a set of evaluation standards to grade their performance in the 13 categories listed in Box 3-2. The self-assessment results can be used to develop phased improvement plans that support continuous improvement of the SMS. TMSA results are divided into four levels, where Level 1 indicates the

___________________

48 K. Coelho and A. Gour, OCIMF, presentation to the committee, January 2023. See also OCIMF, “SIRE 2.0,” accessed March 26, 2024, https://www.ocimf.org/programmes/sire-2-0; Craig Jallal, “SIRE 2.0 Is Here. Are You Ready?” Riviera, December 1, 2023, https://www.rivieramm.com/news-content-hub/news-content-hub/sire-20-is-here-are-you-ready-78672.

49 K. Coelho and A. Gour, OCIMF, presentation to the committee, January 2023.

BOX 3-2

TMSA Elements of Gas Carrier Safety

OCIMF’s TMSA programa requires examination of 13 elements that make up gas carrier safety:

- Leadership and the Safety Management System

- Recruitment and Management of Shore-Based Personnel

- Recruitment, Management and Wellbeing of Vessel Personnel

- Vessel Reliability and Maintenance including Critical Equipment

- Navigational Safety

- Cargo, Ballast, Tank Cleaning, Bunkering, Mooring and Anchoring Operations

- Management of Change

- Incident Reporting, Investigation and Analysis

- Safety Management

- Environmental and Energy Management

- Emergency Preparedness and Contingency Planning

- Measurement, Analysis and Improvement

- Maritime Security

__________________

a OCIMF, Tanker Management and Self-Assessment 3: A Best Practice Guide, 2017. https://www.ocimf.org/publications/books/tanker-management-and-self-assessment-3.

vessel complies with IMO/flag state and classification society requirements. Levels 2–4 indicate an SMS in excess of baseline legal requirements. TMSA results are incorporated into SIRE inspections.50

Charterers use audited TMSA results when contracting with gas carriers. In today’s market, most charterers and terminals would require a vessel to meet a minimum of an audited TMSA Level 2 for a charter of even a single voyage. Therefore, a vessel in compliance with only Level 1, the threshold legal requirement, is not likely to find employment or commercial success as a gas carrier, especially in the U.S. export trade. For a long-term project with a multiple-year charter, which is very attractive to vessel owners because of the steady multi-year cash flow, an audited Level 2 or 3 is normally required before the charter is awarded. This TMSA level then must be maintained during the charter term, or the charter could be terminated or the vessel denied entry to the terminal. It

___________________

50 See also OCIMF, Tanker Management and Self-Assessment 3: A Best Practice Guide, 2017.

is difficult, and expensive, to obtain and consistently maintain an audited TMSA Level 3 or higher.51

Condition Assessment Program

Classification societies offer Condition Assessment Programs (CAPs), which are voluntary services used to assess the fitness of older ships through an independent evaluation of the condition of a vessel. Initially developed by the oil industry in the late 1980s, CAPs have expanded to other types of vessels, including gas carriers. CAP evaluations provide a detailed survey of the ship’s structure, including thickness measurements, as well as extensive testing of the vessel’s machinery, equipment, and cargo systems. They also conduct a strength and fatigue engineering analysis. The evaluation can take 10 days and results in a numeric rating for the vessel. A CAP 1 rating indicates that the condition of the vessel is similar to that of a vessel not more than 5 years of age. A CAP 2 rating signifies that the vessel’s condition is similar to a vessel not more than 10 years of age. Third parties can use the CAP rating to assess whether a vessel is suitable for charter based on its current condition rather than the vessel’s age.52

EXPANSION OF COAST GUARD SAFETY ASSURANCE PROGRAMS

Since 2000, the Coast Guard has developed two additional safety-related initiatives that apply to gas carriers: the QUALSHIP 21 Initiative, which targets all foreign-flag vessels, and the LGC NCOE, which provides advice, training, and surge support for Coast Guard operational commands.

QUALSHIP 21 Initiative

Coast Guard efforts to eliminate substandard shipping traditionally focused on improving methods to identify and target poor-quality vessels. Foreign-flag vessels would typically be examined at least once per year, regardless of safety record. To provide incentives for the “well-run, quality ship” and to reward vessels for their commitment to safety, the Coast Guard initiated QUALSHIP 21 in 2001 to recognize and reward vessels, vessels operators, and flag administrations for their commitment to safety and quality. Enrollment in QUALSHIP 21 is by vessel. To be eligible for QUALSHIP 21, a

___________________

51 K. Coelho and A. Gour, OCIMF, presentation to the committee, January 2023, and follow-on discussion.

52 See, for example, ABS, “Condition Assessment Program (CAP) for Aging Vessels,” accessed March 25, 2024, https://ww2.eagle.org/en/Products-and-Services/marine/condition-assessment-program-cap.html.

vessel must have had no detentions in the past 36 months, any of the other vessels owned or operated by the company must have had no detentions in the past 24 months, and the vessel flag state and classification society must meet certain performance standards.53

Depending on the vessel type, ships enrolled in QUALSHIP 21 receive a reduction in COC examination scope, are issued a certificate, and the vessel name is recognized on the QUALSHIP 21 and Electronic Quality Shipping Information System (EQUASIS) websites.54 For example, vessels enrolled in QUALSHIP 21 are only examined once every 2 years, while other vessels that are not in the program are examined annually. However, the Coast Guard is currently unable to reduce the COC examination frequency of vessels enrolled in QUALSHIP 21 because federal law specifies that an annual exam must be conducted.55 Yet if the enrolled vessel is in both QUALSHIP 21 and another program known as E-Zero, Coast Guard has extended the 3-month window beyond the annual exam to 6 months.56

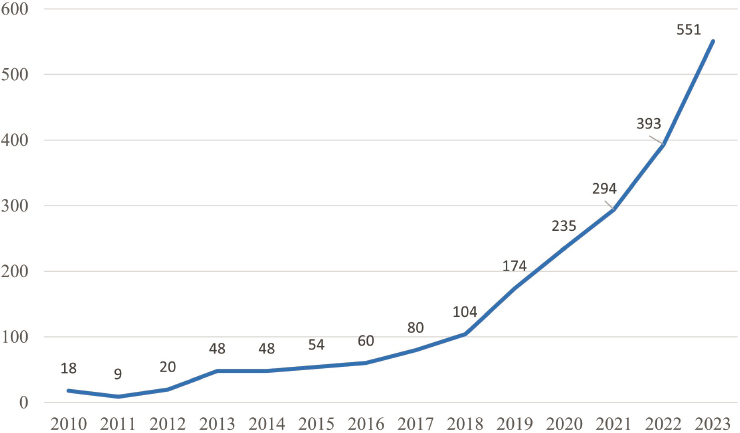

Even without a reduction in COC examination frequency, gas carrier participation in the QUALSHIP 21 program has expanded, steadily increasing from 9 gas carriers in 2011 to more than 550 gas carriers in 2023 (see Figure 3-3).

Liquefied Gas Carrier National Center of Expertise

The Coast Guard embarked on founding National Centers of Expertise (NCOEs) in 2007 as part of its “Marine Safety Enhancement Plan” and in response to a need for a targeted revitalization of technical competency and expertise to keep pace with increasing growth and complexity in the maritime industry.57 In addition to NCOEs for cruise ships, towing vessels, vintage vessels, outer continental shelf activities, casualty investigations, and suspension and revocation of merchant mariner credentials, the LGC NCOE was founded in Port Arthur, Texas, as a detached unit of the Coast Guard Headquarters Traveling Inspector staff.

___________________

53 Coast Guard, “QUALSHIP 21 Initiative,” accessed March 24, 2024, https://www.dco.uscg.mil/Our-Organization/Assistant-Commandant-for-Prevention-Policy-CG-5P/Inspections-Compliance-CG-5PC-/Commercial-Vessel-Compliance/Foreign-Offshore-Compliance-Division/Port-State-Control/QS21.

54 See https://www.dco.uscg.mil/Portals/9/DCO%20Documents/5p/CG-5PC/CG-CVC/CVC_MMS/CVC-WI-002(1).pdf.

55 46 USC 3714 inspection and examination.

56 See https://www.dco.uscg.mil/Portals/9/DCO%20Documents/5p/CG-5PC/CG-CVC/CVC2/psc/safety/qualship/QS21_EZero.pdf.

57 Coast Guard Message, ALCOAST 131/09, Subj: National Centers of Expertise (NCOE).

SOURCE: U.S. Coast Guard data (provided to the committee), 2023.

Although NCOEs have some military personnel, many civilian employees are employed to provide the needed stability, consistency, and industry knowledge for their long-term success.58 The NCOEs are expected to

- revitalize the Coast Guard’s technical competency and expertise to keep pace with the growth and complexity of the maritime industry;

- provide key venues for professional development and exchange between industry and Coast Guard personnel;

- enhance Coast Guard inspector and investigator capabilities while promoting nationwide consistency;

- become a repository of Coast Guard expertise and best practices within their respective maritime industry sector;

- assist in the standardization of techniques and processes across the Coast Guard;

- establish and cultivate enhanced working relationships and partnerships with public and private industry stakeholders to include professional training exchanges and joint training initiatives;

___________________

58 Coast Guard Annual Update Supplement to the Marine Safety Performance Plan, March 2010.

- provide consultation concerning unique design, examination, and operational situations and development of regulations, policy, and doctrine, as requested;

- monitor field activities and procedures to ensure uniform application of regulations, policy, and doctrine; and

- develop curriculum for both exportable and resident training courses.59

Although the LGC NCOE currently has only eight people on staff, many industry and other Coast Guard stakeholders informed the committee that the LGC NCOE has had significant positive impacts.60 The LGC NCOE has successfully increased the Coast Guard’s gas carrier competency, capabilities, and inspection consistency. LGC NCOE personnel keep pace with industry change and improve inspector knowledge and proficiency by supporting and providing gas carrier workshops, on-the-job training, industry training opportunities, gas carrier ship rides, training videos, and specialized input to the development of Coast Guard gas carrier inspection techniques, practices, and qualification requirements.61

The LGC NCOE serves industry as well as Coast Guard field units. Waterfront facility operators that handle liquefied gases and companies that operate gas carriers can and do direct specific technical issues and questions to the LGC NCOE, trusting that the knowledgeable staff will provide timely and informed responses.62 Similarly, Coast Guard field units regularly turn to the LGC NCOE for support. The LGC NCOE augments the marine inspector workforce from the field units with additional highly experienced gas carrier marine inspectors who provide specialized gas carrier expertise and technical advice to the field unit and sometimes assist with COC examinations. In 2021 and 2022, personnel from the LGC NCOE participated in approximately 10% of the COC exams completed by the Coast Guard. However, the LGC NCOE does not have sufficient personnel or resources to attend COC examinations of all liquefied gas carriers (LGCs) in all U.S. ports.

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE EXAMINATION PROCESS

The COC examination process is a multiple-step process that starts well before a gas carrier enters a U.S. port. In advance of a foreign-flag gas

___________________

59 Ibid.

60 Workshop presentations to the committee in Houston, Texas, March 2023. See https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fo/tokkjlryemozxp1ssnk60/h?rlkey=sybtyfnf2zok9sszaucqcx9mu&dl=0.

61 LGC NCOE, presentation to the committee, March 2023.

62 Workshop presentations to the committee in Houston, Texas, March 2023. See https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fo/tokkjlryemozxp1ssnk60/h?rlkey=sybtyfnf2zok9sszaucqcx9mu&dl=0.

carrier’s first visit to a U.S. port, the vessel owner or operator must submit design drawings, certificates, and information to the Coast Guard Marine Safety Center (MSC), which is located in Washington, DC, and provides engineering and technical support to Coast Guard field units.63 The Coast Guard MSC reviews the submitted information to verify that the foreign gas carrier is in compliance with the U.S. design requirements. The standard turnaround time for review by the Coast Guard MSC is 30 days; when complete, the Coast Guard MSC will develop an SOE, which describes the specific cargo that the vessel is allowed to carry. The Coast Guard MSC must complete and approve the SOE before the vessel’s first COC examination can be scheduled.

To receive the COC and SOE, the gas carrier must call at a U.S. port for examination by the Coast Guard to determine compliance with the applicable regulations.64 When the vessel is due for a COC exam (initial, annual, or renewal), the gas carrier owner, operator, or agent is required to provide the Coast Guard at least 7 days advance notice to arrange the exact time and location of the exam.65 In addition, before the examination will be conducted, the owner or operator must pay an examination fee to the U.S. Department of the Treasury.66

Risk Assessment and Vessel Targeting

All foreign-flag gas vessels are required to provide notice of arrival (NOA) information at least 96 hours prior to arriving in the United States. The local Coast Guard office in each U.S. port screens each of these vessels before they arrive using three risk-based matrices to determine their risk level or threat. The PSC Safety and Environmental Protection Compliance Targeting Matrix evaluates risk factors related to the vessel’s compliance with international safety and environmental standards and is intended to enable the Coast Guard to identify those vessels that pose the greatest risk of being substandard. The other two matrices assess a vessel’s security risk.67

Marine Information for Safety and Law Enforcement (MISLE) is the Coast Guard’s primary information management tool for planning, scheduling, executing, monitoring, and tracking all activities associated with foreign vessels. MISLE automatically applies the PSC Safety and

___________________

63 46 CFR 154.22. Safety Standards for Self-Propelled Vessels Carrying Bulk Liquefied Gases.

64 46 CFR 154.150. Safety Standards for Self-Propelled Vessels Carrying Bulk Liquefied Gases.

65 46 CFR 154.151. Safety Standards for Self-Propelled Vessels Carrying Bulk Liquefied Gases.

66 46 CFR 2.10. Fees.

67 COMDTINST 16000.73, Marine Safety: Port State Control (D4-1), September 2021.

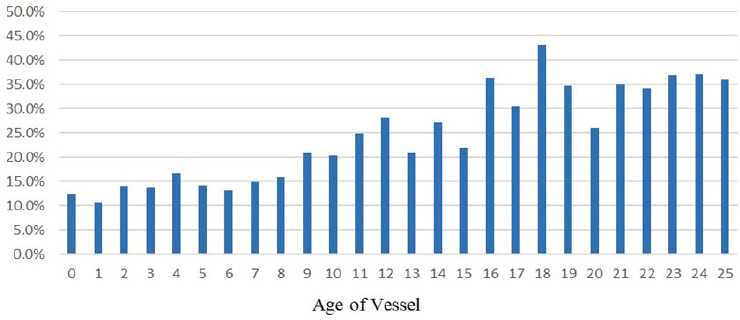

Environmental Protection Compliance Targeting Matrix to foreign vessels that submit an NOA. This risk-based approach evaluates vessels based on six criteria: (1) time elapsed since the vessel was last examined by the Coast Guard; (2) performance of the flag state; (3) performance of the ship management company and detention history of vessels under its control; (4) performance of the RO; (5) history of compliance, which includes Coast Guard deficiency history, and involvement in marine casualties or violations and detentions by the Coast Guard or other governments that are party to the Paris or Tokyo MOUs; and (6) the vessel type and age.68

MISLE also allows the Coast Guard direct access to EQUASIS, which is a database of inspection data/results from Port State regimes around the world. Though EQUASIS is not used to score a vessel in the Coast Guard matrix, PSCOs are highly encouraged to use the system to obtain additional information regarding the safety history and overall condition of the vessel.

In general, all vessels that have not received a Coast Guard PSC exam in the previous 12 months will be a priority and undergo a Coast Guard PSC exam. The Coast Guard routinely de-prioritizes annual exams for container vessels, bulk carriers, or other types of cargo vessels that are enrolled in QUALSHIP 21 and that have received a Coast Guard PSC exam within the past 2 years. However, tank ships including gas carriers, even if they are enrolled in QUALSHIP 21, must receive a calendar-based annual exam because it is required by U.S. law to maintain the COC.69

Scheduling Exams

To avoid delays in cargo operations during a future visit to a U.S. port, gas carrier vessel owners and operators sometimes request an examination even though the COC is valid and an exam is not yet required. Coast Guard policy encourages OCMIs/COTPs to complete the COC exam when requested if the COC is within 3 months of expiration.70 However, input received by the committee from industry and Coast Guard stakeholders indicates that the Coast Guard is often unable to conduct these exams due to a lack of personnel resources.71

___________________

68 COMDTINST 16000.73, Coast Guard Marine Safety Manual, Vol. II: Materiel Inspection Section D: Port State Control, Chapter 4: Targeting of Foreign Vessels, D4-17, September 2021. See also Coast Guard Office of Commercial Vessel Compliance (CG-CVC) Mission Management System (MMS) Work Instruction (CVC-WI-021(1)), Targeting of Foreign Vessels for PSC Examination, January 13, 2020.

69 46 USC 3714 Inspection and examination.

70 COMDTINST 16000.73, Marine Safety: Port State Control (D6-5), September 2021.

71 Workshop presentations to the committee in Houston, Texas, March 2023. See https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fo/tokkjlryemozxp1ssnk60/h?rlkey=sybtyfnf2zok9sszaucqcx9mu&dl=0.

The Coast Guard tries to accommodate vessel schedules and will generally conduct exams any day of the week, including weekends. Sector Houston-Galveston can perform up to three COC exams on a Saturday or Sunday, while the much smaller Marine Safety Unit Lake Charles typically is only able to do one exam per day on weekends. The Coast Guard prioritizes vessels that are restricted from conducting cargo or from departing due to an overdue annual or expired COC exam. However, to ensure the marine inspectors can see the full condition of the vessel, conducting exams during daylight hours is essential.

Typically, the Coast Guard will not travel offshore for COC exams, except for lightering vessels that do not come into port. In addition to the increased safety risk associated with the transfer of the PSC team via helicopter or boat, offshore exams take considerably more time due to the additional transportation and logistics, significantly reducing the inspection team’s efficiency and ability to conduct multiple exams in one day. If transportation offshore is via helicopter, Coast Guard members must receive emergency egress training and require costly safety equipment that also limits access for training new inspectors.

Conducting Exams

After the COC exam is scheduled, a PSC team is assigned by the Coast Guard office. Each PSC examination team should contain a minimum of two members and a maximum of five, including trainees. One member must be an officer, chief warrant officer, or civilian marine inspector, with a foreign gas carrier examiner (FGCE) qualification. The second member should, at a minimum, be qualified as a PSCE.72 In an effort to expedite the exam, Coast Guard members interviewed by the committee stated that they typically assign up to four people to conduct a COC exam, and the team is divided to cover different areas of the vessel.

The inspection team conducts the COC exam according to the guidance found in the Coast Guard’s Foreign Gas Carrier Job Aid.73 The job aid contains an extensive list of possible examination items but states, “[I]t is not, however, the Coast Guard’s intention to ‘examine’ all items listed.” The depth and scope of the exam is to be determined by the PSCOs based on the condition of the ship, operations of the ship’s systems, and the competency of the crew.74

___________________

72 COMDTINST 16000.73, Marine Safety: Port State Control (D1-6), September 2021.

73 COMDTINST 16000.73, Marine Safety: Port State Control (D1-52), September 2021.