Intermodal Chassis Provisioning and Supply Chain Efficiency: Equipment Availability, Choice, and Quality (2024)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

BACKGROUND

Most general cargo in international commerce moves from origin to destination in standardized 20-ft, 40-ft, or 45-ft steel box containers (see Figure 1-1). Containers imported to the United States by ship are transferred at seaports to railroads and trucks for movement to inland destinations. The process is reversed for containers that are empty or used for exporting cargo. While this process was brought to a near standstill by the COVID-19 pandemic in the first half of 2020, the demand for containerized shipping surged later that year and during 2021 and 2022 as the economy recovered with record consumer spending that caused retailers, manufacturers, and other shippers of containerized cargo—known as the beneficial cargo owner (BCO)—to sharply increase their orders for imported goods. Additional logistics capacity, including container ships, empty containers, and personnel, could not be deployed fast enough to meet this global rebound in transportation demand.

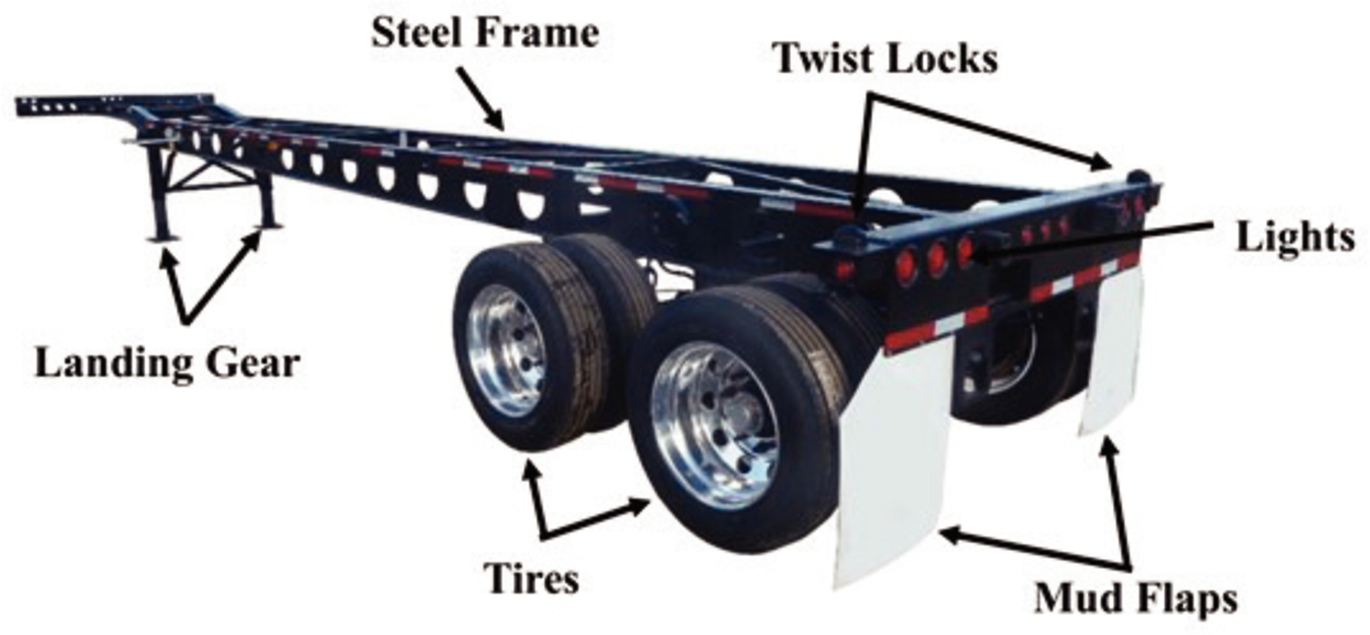

Among the many transportation assets in short supply, or out of position, were the chassis that motor carriers use to move containers between seaport and rail terminals and inland warehouses and distribution centers. These movements are commonly referred to as intermodal container drayage. Designed and sized specifically for transporting shipping containers, the chassis used for container drayage are truck trailers consisting of a frame,

SOURCE: Adapted from https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/economy/shipping.html.

two or three axles, and mechanisms for locking the container in place (see Figure 1-2).1

While chassis shortages created acute problems during 2021 and 2022, other concerns related to the availability and sourcing of chassis preceded the onset of the pandemic, and some of them persist to this day. Prompted in part by the Great Recession and the introduction of new federal safety regulations applicable to chassis, the way this equipment was being supplied for intermodal container drayage in the United States had been evolving for more than a decade before the pandemic. The new safety regulations, issued in 2008, made the companies that tender chassis subject to many of the same rules for vehicle inspection, maintenance, and repair that apply to motor carriers. At that time, most chassis were owned by ocean carriers, who provided the equipment to motor carriers for drayage services. No longer interested in being equipment providers, the ocean carriers began divesting their large chassis fleets to independent companies in the wake of the Great Recession and the introduction of the new safety rules. Thus, motor carriers would now need to obtain the equipment from these intermodal equipment providers (IEPs) unless they had access to their own chassis.

In divesting their large chassis fleets, ocean carriers entered into contracts with the IEPs to provide chassis for their container shipments, and especially for the portion of traffic in which the ocean carrier has arrangements with the BCO to coordinate the entire container transportation service from the exporting port to a designated delivery point. Motor carriers

___________________

1 In this report, the term chassis is used to refer to a frame or trailer designed to carry intermodal shipping containers.

SOURCE: Adapted from Rodrigue, 2024.

providing drayage service would therefore need to use a chassis from the preferred IEP of the ocean carrier that owns the container and coordinates and pays for the entire transportation service. In cases where the ocean carrier’s transportation service agreement with the shipper is limited to linehaul movements and not local delivery, a motor carrier hired by the BCO for drayage could potentially use its own chassis or obtain one from an IEP by paying a short-term rental fee to be reimbursed by the BCO.

Facilitated by local port authorities, the IEPs in many drayage markets worked out arrangements to create interoperable (“gray”) chassis pools, whereby any of the chassis of the IEPs contributing to the pool could be used by a motor carrier to satisfy an ocean carrier’s requirement that a motor carrier use the chassis of a specific IEP. Similar pools had existed when the ocean carriers controlled most chassis. These pooling arrangements were intended to make it easier for motor carriers to find the chassis needed to move a specific container, while also reducing the total number of chassis needed by an individual IEP to meet peak demands from its partner ocean carriers. The pooling arrangements, however, raised concerns related to the way motor carriers are billed for the use of the pooled chassis and questions about whether IEPs are motivated to contribute high-quality equipment. Furthermore, the extent to which the partnerships forged by ocean carriers and IEPs had permeated the chassis provisioning system raised concerns about whether resulting constraints on chassis sourcing are inconducive to the operational efficiency of drayage services.

Thus, even as the pandemic’s aftermath cast a spotlight on the critical role of chassis in the logistics system, concerns about chassis provisioning practices in the United States have had roots farther back in time. Indeed,

in September 2019, months before the pandemic led to chaos in the global supply chain, the U.S. Senate directed the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) to identify the advantages and disadvantages of different chassis provisioning models, taking into account local conditions at ports; business relationships among shippers, carriers, and IEPs; and public interests in curbing port congestion and ensuring chassis safety.2 In giving GAO this direction, the Senate Appropriations Committee reported that:

[It] is aware of the benefits of the American freight delivery system, specifically the flexibility and safety benefits that chassis pooling provides to shipping companies, marine terminal operators, ocean carriers, truckers, rail operators, and intermodal equipment providers. However, in an evolving and dynamic industry with a variety of demands on the supply chain based on region, market, and cargo volumes, issues can arise impacting chassis availability. The Committee is aware of various reports as a result of these issues, including unexpected fees imposed on both truckers and shippers, non-negotiable terms found in chassis contracts and leases, and higher levels of port congestion resulting in insufficient chassis availability. These issues can lead to a lack of competitive market, service disruptions, and increased supply chain costs without any corresponding benefit.

The GAO report,3 issued on March 8, 2021, examined the role of the two main federal agencies responsible for overseeing and regulating aspects of chassis economics and safety—the Federal Maritime Commission (FMC) and the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA). FMC oversees ocean carriers that serve the United States, as it is charged with promoting a competitive and reliable ocean transportation system. One of its functions is to review agreements among relevant parties that may discuss or provide chassis or create interoperable chassis pools. The agreements must conform with relevant statutes, including FMC rules interpreting the Shipping Act of 1984 and its emphasis on a nondiscriminatory regulatory process for waterborne foreign commerce. FMCSA regulates the safety of the commercial motor vehicle industry, including the safety performance of IEPs and chassis. In this role, FMCSA establishes inspection standards for the motor carriers and truck drivers that use chassis.

In conducting its report, the GAO consulted a range of stakeholders to identify the advantages and disadvantages of the different models for supplying chassis in United States, including motor carrier–controlled chassis operations and sourcing from single IEPs and interoperable pools. Reported advantages of the motor carrier–controlled model include the motor carrier

___________________

2 Transportation, and Housing Urban Development, and Related Agencies Appropriations Bill, 2020, September 19, 2019, p. 162, Report 116-109.

being assured of a chassis being available and having control over the equipment’s condition and quality. Likewise, the single IEP model (i.e., proprietary fleet) has the advantage of the IEP having direct control over equipment condition and quality, and potentially the incentive to upgrade the equipment to attract business. A key advantage of the interoperable pool is that the chassis from contributing IEPs are interchangeable so that any chassis in the pool can be used by any motor carrier to move any ocean carrier’s containers. As reported by GAO, this feature can reduce the time spent and miles driven by truck drivers retrieving and returning empty chassis to comply with ocean carrier and IEP sourcing agreements. Furthermore, containers can be placed directly on any pooled chassis at the port and rail terminal prior to the driver’s arrival, speeding up the drayage process and facilitating terminal operations. Interoperable pools also can reduce the total number of chassis needed in a market, including keeping their storage footprint to a lower level, as participating IEPs can rely on pooled chassis to cover the peak demand periods of their partner ocean carriers.

GAO also noted that drawbacks were reported for each of the models. For instance, at port and rail terminals where containers may be unloaded from the ship or train directly onto an IEP’s chassis (known as a “wheeled” operation), a motor carrier arriving with its own chassis may need to wait and pay for the chassis to be transferred or “flipped” to a chassis controlled by the terminal. Furthermore, in the motor carrier–controlled model, the trucking company is responsible for the costs of owning, leasing, and maintaining the chassis, which may be a drawback for some local drayage companies with limited capital. For motor carriers with small chassis fleets, the possibility that a chassis may need to be left for several days at the destination for removal or unloading can be another drawback to this model. In the case of interoperable pools, a reported disadvantage is that participating IEPs may not see value in contributing their highest-quality chassis since they are not guaranteed a return on their investment in quality. Gray pool participants may also object to the loss of control over chassis maintenance and repair, which is generally handled by pool managers.

Characterized as an “audit,” the GAO report does not delve into these business-related reasons for alternative chassis provisioning and container haulage models, nor their net benefits from the standpoint of ocean carriers, railroads, motor carriers, IEPs, pool managers, and BCOs. Given the wide array of business interests and market conditions, and the private contractual arrangements that underpin the models and their use, such a full and objective accounting of the advantages and disadvantages of the models would have been impractical. The GAO report, however, does point to public interests that warrant consideration when reviewing the alternative chassis provisioning models. In calling for the GAO report, the Senate referenced such public interests in asking about impacts on chassis

safety and road traffic congestion at ports. On these matters, the GAO report observed that motor carrier–controlled chassis and gray pools could reduce truck movements within and around ports and rail terminals as drivers make fewer trips to retrieve and return empty chassis to individual IEPs in compliance with box rules. At the same time, it was noted that if the IEPs in interoperable pools are disincentivized to upgrade the quality of their pooled chassis, this effect could manifest itself in degraded road safety performance.

STUDY ORIGINS AND CHARGE

The GAO report helped inform the Ocean Shipping Reform Act of 2022, enacted on June 16, 2022. In Section 19 of the act, Congress called on FMC to commission the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) to study “best practices for on-terminal or near-terminal chassis pools that provide service to marine terminal operators, motor carriers, railroads, and other stakeholders that use the chassis pools, with the goal of optimizing supply chain efficiency and effectiveness.” The legislative direction also asked that consideration be given to relevant communications, information sharing, and knowledge management practices and capabilities that can facilitate chassis provisioning.

In September 2022, FMC commissioned this study by an expert committee in fulfillment of Section 19, negotiating the study task statement shown in Box 1-1. It merits noting the special interest, as indicated in both the legislative language and task statement, in the identification of chassis provisioning practices that are “efficient” and can increase “supply chain efficiency.” “Efficiency” is not defined in either text, but for reasons that are explained next, the study committee chose to consider efficiency in a broader societal-level, rather than business-focused, context that accounts for the external effects on the public of different chassis provisioning practices, which is consistent with the Senate’s interest in accounting for effects on port congestion and road safety.

STUDY APPROACH

The committee began its work by reviewing the 2021 GAO report and other documents recounting the history and evolution of chassis provisioning practices in the United States. The most detailed account of this history through the first decade of the 2000s appears in National Cooperative Freight Research Program (NCFRP) Report 20, Guidebook for Assessing Evolving International Container Chassis Supply Models. Issued in 2011, the NCFRP report was released just as ocean carriers were divesting their chassis fleets and new intermodal equipment provisioning practices were

BOX 1-1

Statement of Task

An ad hoc committee will study approaches for supplying the chassis used by motor carriers, railroads, and marine terminal operators to transport intermodal containers. The committee will examine the different chassis provisioning models in use, with a focus on equipment ownership and fleet management, equipment availability and interoperability, and equipment maintenance, repair, and upgrading. The committee will identify advantages and disadvantages of the alternative models and fleet management practices under different scenarios such as port size, traffic activity, and operational complexity. Consideration will be given to evaluating whether the models have aligned incentives in equipment ownership, management, maintenance, and provisioning that lead to supply chain efficiency. Additionally, the committee will evaluate the incentives for employing efficiency-enhancing communications, information sharing, and knowledge management practices across chassis provisioning models.

Informed by these findings, the committee will identify the circumstances under which individual models for provisioning chassis are optimized for the efficient functioning of the supply chain, including best practices from each model that can further increase efficiency. The committee will identify the conditions necessary to implement each model, including practical obstacles to implementation and their possible solutions. The committee may make recommendations to the sponsor, industry, Congress, and others, as appropriate, on measures to increase the efficiency of chassis provisioning.

being introduced. The report concluded that it could take a decade for these developments to play out. Indeed, while much has changed in the chassis supply market since 2011, the NCFRP report provided the committee with many helpful insights into the origins and evolution of the practices that now exist in drayage markets.

Informed by recent history and having to decide on how best to fulfill the Statement of Task, the study committee came to the view that it would be important to consider chassis provisioning practices and their efficiency implications from a societal perspective that considers the views of specific stakeholder groups (i.e., carriers, BCOs, IEPs, and ports) but does not necessarily attempt to define best practices from each of their varied perspectives. Given the complexity of relationships among stakeholders, the intricacies of individual drayage markets, and the fact that business practices and market conditions are subject to change, the committee concluded that it should pay particular attention to practices for chassis provisioning that can promote the public interest, which is furthered by a resilient and flexible supply chain.

After its meetings with a variety of intermodal shipping stakeholders and visits to several local drayage markets, the committee became even more convinced that a study of best practices for chassis provisioning would need to proceed with caution. The committee was provided with a great deal of anecdotal evidence and claims about behaviors and their adverse effects, but not a supporting base of facts in many cases. Significantly, many of the practices that were the subject of the complaints raised by stakeholders stem from contractual arrangements among carriers, IEPs, and BCOs. In not being privy to the terms and conditions in these contracts, the committee could not confidently evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of specific practices and features of the chassis provisioning system. The committee cannot know, for instance, if a contractual agreement that obligates a dispatched motor carrier to source a chassis from an IEP designated by an ocean carries has conditions that favor the BCO, even when this practice is not desirable from the standpoint of the motor carrier.

Realizing that it would not be in a position to make judgments about best practices for chassis provisioning as they apply to individual stakeholders, the committee nevertheless wanted to hear their comments, concerns, and complaints about practices as they exist and have evolved in a selection of international container drayage markets, both at seaports and inland rail terminals. Thus, to further its understanding of the issues involved in chassis provisioning, the committee invited relevant experts and interested parties to meetings to offer their views on practices. The committee also visited port complexes on the West and East Coasts and two inland rail terminals to consult with port authorities, terminal operators, chassis suppliers, motor carriers, BCOs, railroads, and labor representatives. While the committee could only visit a limited number of sites, its aim was to sample an assortment of locations where chassis are supplied under differing circumstances and conditions and to ensure input from a range of stakeholders. The locations visited and parties consulted are listed in the preface.

It merits noting that during information-gathering, the committee encountered challenges arising from ongoing litigation on chassis provisioning involving motor carriers and ocean carriers that made some of the involved parties cautious or reluctant to share their views and relevant information.4 While the committee was able to partially compensate for these information gaps by tapping a wide range of additional information, the array and quality of quantitative data available for analysis proved limited. An especially informative database proved to be FMCSA’s multi-year records of motor carrier roadside inspections. The data provided insights about on-road chassis ages and physical condition.

Asked to make recommendations, as appropriate, to FMC, industry,

___________________

4 Federal Maritime Commission, Docket No. 20-14.

and Congress on measures to increase the efficiency of chassis provisioning, the committee remained committed to its views that efficiency should be examined with a heavy emphasis on the public interest, especially on the imperative of ensuring traffic safety, because chassis are prevalent on public roads. Having recently witnessed how disruptions to the global supply chain can have widespread ramifications on the economy and society, the committee also sought to pay particular attention to opportunities for improving the development and exchange of information relevant to chassis supply and demand balances and to furthering supply chain fluidity and resilience.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

The next chapter provides more background on international container shipping and the role of chassis in the freight transportation process. The evolution of the chassis provisioning system over the past 10 to 15 years is discussed, including a recap of problems encountered following the pandemic. The chapter also describes the key stakeholders in the container shipping enterprise. Chapter 3 explains how the committee consulted with these stakeholders to identify advantages and disadvantages of the chassis provisioning system as they see them. Informed by these consultations, the chapter focuses on issues related to contractual agreements for sourcing chassis, equipment condition and quality, and the visibility and timeliness of supply chain data. Many of the concerns expressed by stakeholders related to chassis provisioning pertained to one or more of these issues. Chapter 4 focuses on chassis condition and quality and how the federal government oversees, regulates, and monitors equipment roadworthiness. A review of roadside inspection data provides insights into the effectiveness of these efforts and those of industry. The report concludes, in Chapter 5, with a summary assessment and the committee’s findings and recommendations.

This page intentionally left blank.