Intermodal Chassis Provisioning and Supply Chain Efficiency: Equipment Availability, Choice, and Quality (2024)

Chapter: 3 Stakeholder Views on Chassis Provisioning Practices

3

Stakeholder Views on Chassis Provisioning Practices

The discussion in the previous chapter reveals the complexity of the international container shipping container system and the U.S. landside transportation system that connects container ports with inland importers and exporters. Certain features of this intermodal transportation enterprise are unique to the United States, including the varied means by which chassis are sourced for drayage services. Throughout most of the world, chassis are owned and controlled by the motor carriers that supply the drayage service. The provision of chassis by third-party intermodal equipment providers (IEPs) for short-term rental is a feature not found in other countries. Furthermore, the common use of two different methods for arranging drayage, through ocean-carrier control (carrier haulage) and merchant control (merchant haulage), is another feature of the system unique to the United States that has a significant bearing on chassis provisioning.

The U.S. container shipping system is enormous in scale, scope, and heterogeneity. In addition to involving international ocean carriers, the inland legs of the system include all major domestic freight railroads; hundreds of national, regional, and local drayage carriers; several national IEPs along with smaller regional IEPs and pool managers; and dozens of ports and intermodal terminal operators. This intermodal system also contains scores of drayage markets with varying traffic volumes, chassis storage space, labor agreements, institutional settings, import–export balances, market sizes, terminal numbers and types (i.e., wheeled, grounded, hybrid), and terminal locations in relation to one another and public highways. As a result of this diversity, the committee early on questioned whether it would be able to identify “best practices” for chassis provisioning, even for drayage markets

sharing certain characteristics related to geography, traffic activity, and mode mix.

While all the parties involved in the logistics system for shipping intermodal containers can be characterized as “stakeholders,” the system’s end purpose is to satisfy the interests of the cargo shipper and receiver customers, or BCOs. Therefore, the premise of this study, as explained in Chapter 1, is that a review of the country’s chassis provisioning practices should focus foremost on each practice’s effectiveness in serving the interests of BCOs while minimizing externalities to the public. In this regard, however, individual BCOs will have their own preferences about how the logistics systems should perform, weighing service attributes differently, such as the relative importance of transportation price, speed, reliability, and transaction convenience. Viewed from the outside, it is not possible to infer these varied BCO preferences or standardize them because they derive from a wide variety of economic sectors, from importing retailers, manufacturers, and distributors to exporting manufacturers and commodity suppliers, all of them operating under different economic and physical environments. Moreover, it is not possible to see the full picture of how a BCO’s confidential arrangements with carriers may satisfy its preferences, and this applies to their contractual arrangements for chassis sourcing as well.

The 2021 GAO audit, as discussed in Chapter 1, consulted a selection of parties involved in the intermodal container shipping system in the United States about their experience with alternative chassis provisioning models. In doing so, GAO identified a number of advantages and disadvantages of alternative models, but without making distinctions about how the reported advantages and disadvantages may benefit or harm the chassis and transportation providers or the BCOs who are the end users of the container shipping system. GAO’s findings were summarized in Chapter 1. This chapter synthesizes the feedback provided to the study committee about the advantages and disadvantages of chassis provisioning models. The feedback was obtained from written submissions and during information-gathering sessions in Washington, DC, and in conjunction with visits to coastal and inland drayage markets. As with the GAO report, this solicitation of stakeholder views was limited to parties who were willing to provide them. Given the scale, scope, and variability of the country’s container shipping system, the committee realized that its outreach efforts could very well miss some important perspectives, but nonetheless believes that the efforts undertaken and conversations with willing parties provide important insights.

The next section describes the types of stakeholders consulted and the intermodal shipping markets visited by the study committee to elicit views on the practices and features of the U.S. chassis provisioning system. This is followed by a summary of those views by type of stakeholder, focusing on

the IEPs and intermodal carriers (ocean carriers, railroads, and motor carriers). For these providers of container transportation services, some of the features of the chassis provisioning system may be viewed as advantages, while for others, the same features may be viewed as disadvantages. This outcome should not be surprising in markets where firms are competing, focused on specific aspects of the container move, and intent on furthering their competitive positioning and pursuing their own business interests within an interconnected set of transactions.

Even though the transportation stakeholders in the container shipping enterprise may favor certain system features and dislike others, one would expect that the variety of features and practices that prevail provides a functional inland container transport system, supporting the BCO’s fundamental interests in a manner that is efficient at providing responsive and dependable service. These interests, of course, should be aligned with the public’s interest in a container shipping system that is efficient in the sense that it does not create undue externalities, including highway safety risks, off-terminal traffic congestion, and emissions of noise and pollutants. The committee met with officials from public agencies, including the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA), International Trade Administration Office of Supply Chain, Federal Maritime Commission, and several port authorities to hear their views on what constitutes an efficient chassis provisioning system in light of their missions to support supply chain efficiencies and promote the public interest.

The chapter concludes with a summary assessment that takes into account those issues raised by stakeholders about chassis provisioning that may conflict with the interests of BCOs and the public.

OVERVIEW OF CONSULTED STAKEHOLDERS

The study committee spent much of its time during meetings gathering and reviewing information from individuals and entities interested in the study. These participants included industry association officials, company representatives, labor union leadership, and port authority officials. The consultations took place in Washington, DC, and in four locations with major container drayage markets: Savannah, Georgia; Los Angeles/Long Beach (LA/LB), California; Memphis, Tennessee; and Joliet, Illinois. The four visited sites represent some of the country’s most active seaports and rail terminals for international container shipping. LA/LB is the nation’s busiest gateway for containers, while Savannah is the second busiest gateway on the Atlantic seaboard and third busiest nationally. Both are served by Class I railroads for long-distance inland movements and by motor carriers for drayage to regional warehouses and transloading facilities. Joliet, at one end of the LA/LB-Chicago transcontinental corridor, is an eastern terminal for

the Union Pacific and Burlington Northern railroads. The Memphis region is a terminus for all five Class I railroads. Both the Joliet and Memphis inland drayage markets have rail terminals with grounded (stacked) and wheeled facilities, including hybrids of both.

Table 3-1 lists the names of the more than three dozen stakeholders who contributed information to the study through written statements and submitted materials, presentations, and site visits. Although the committee posed a series of questions to many of the parties consulted, information-gathering sessions were open and unstructured to allow participants the freedom to present their views on the chassis provisioning system generally and in specific intermodal markets. Some expressed strong views about existing chassis provisioning practices, while others provided relevant information but did not raise specific concerns or state preferences for changes. Because some of the views expressed were raised during multiparty exchanges, direct attribution to specific individuals and entities is limited mainly to those instances where views are documented in written submissions.

MAJOR CONCERNS RAISED BY STAKEHOLDERS

The committee was able to synthesize the information collected from stakeholders into topic areas that elicited viewpoints that were often shared by parties from the same stakeholder groups. Repeatedly the committee heard concerns, from motor carriers in particular, about issues related to contractual agreements for sourcing chassis, equipment condition and quality, and the visibility and timeliness of supply chain data, including container arrivals and onsite chassis availability. In the sections that follow, these major areas of concern are discussed further from the standpoint of the main stakeholder suppliers of intermodal container transportation services—the ocean carriers, motor carriers, and chassis providers.

Chassis Sourcing Restrictions

The topic raised most often by the consulted stakeholders, and that generated the strongest views, concerns the contractual agreements ocean carriers have negotiated with IEPs for chassis sourcing at an agreed-upon price, which was sometimes referred to as “box rules.” As discussed in Chapter 2, this type of chassis sourcing is a common feature of “ocean carrier haulage” (CH), whereby the ocean carrier supplies the full “door-to-door” container transportation service by offering a bundled rate that includes the linehaul movements (overseas and domestic rail) and local drayage service, including chassis sourcing. In other common contractual arrangements, usually referred to as “merchant haulage” (MH), the BCO and motor

TABLE 3-1 Stakeholders Consulted

| Location | Stakeholder Participants | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Washington, DC | Institute of International Container Lessors Federal Maritime Commission International Trade Administration |

FlexiVan Leasing, LLC TRAC Intermodal Direct ChassisLink, Inc. |

Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration North American Chassis Pool Cooperative, LLC |

| Los Angeles/Long Beach, CA | Harbor Trucking Association Total Transportation Services Port of Los Angeles |

Ocean Carrier Equipment Management Association Consolidated Chassis Management, LLC Yusen Terminals, LLC |

Port of Long Beach International Longshore and Warehouse Union, Local 13 |

| Savannah, GA | Burlington Stores, Inc. Gemini Shippers Association |

Georgia Port Authority NFI/California Cartage |

South Carolina Ports Authority |

| Memphis, TN | Blue Diamond Growers American Cotton Shippers Association Staple Cotton Cooperative Association |

Mallory Alexander International Logistics Intermodal Cartage Company International Express Trucking, Inc. |

TCW Transportation Mohawk Global Direct ChassisLink, Inc. BNSF |

| Joliet/Chicago, IL | Union Pacific ARL Transport, LLC |

C&K Trucking, LLC The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey |

Intermodal Association of North America |

| Other | Wallport Transit Xpress Gulf Winds International, Inc. |

American Trucking Associations/Intermodal Motor Carriers Conference | Virginia Port Authority |

carrier providing drayage service will source the chassis after the container is transported under contract by the ocean carrier to a designated port or rail terminal; however, even these agreements can include clauses in which the BCO may opt to use the chassis nominated by the ocean carrier. A fundamental challenge in characterizing these haulage and chassis sourcing arrangements and their predominance is that hybrids will arise depending on the terms of the confidential contracts among ocean carriers, motor carriers, and IEPs. A haulage arrangement, for instance, may include options for the BCO to source the chassis in accordance with the ocean carrier’s negotiated price with a partner IEP or opt to obtain a chassis from other IEPs or the motor carrier. With the potential for such permutations in mind, potential conflicts among the transport service and equipment providers that can arise from different haulage arrangements are summarized in Box 3-1.

From the standpoint of the ocean carriers and their partner IEPs, the contractual agreements that underpin CH shipping are a standard commercial practice in which the party (the ocean carrier) that has entered an agreement with the customer (BCO) to coordinate and pay for the transportation service negotiates agreements with the downstream service providers, including railroads, equipment suppliers, and motor carriers, for the purpose of establishing the agreed-upon price and obtaining a commitment for service availability and quality. In comments to the study committee by their trade association [Institute of International Container Lessors (IICL)],1 the largest IEPs also pointed out that in those cases where an MH agreement assigns chassis sourcing to the ocean carrier, this arrangement may be desirable if the ocean carrier can obtain the chassis at a lower rental rate than what the motor carrier can obtain. Such an arrangement may also improve operational efficiency or fluidity at “wheeled” terminals where a container is mounted directly onto a pre-staged chassis to facilitate and speed movements from the terminal to the BCO’s designated destination.

The IICL maintained that haulage arrangements where the BCO assigns chassis sourcing to the ocean carrier should not be called “box rules.” Instead, IICL contends that the term derives originally from circumstances in which a motor carrier obtains a chassis from an interoperable pool and is billed by the IEP partnered with the ocean carrier that owns the container or “box” being moved. Under this billing policy, a motor carrier providing merchant haulage that chooses to source a chassis from an interoperable pool may not be able to choose a specific IEP for invoicing even if it assigned responsibility for sourcing the chassis according to the terms of its contractual agreement with the BCO. Instead, the assignment of the invoicing IEP is determined by the owner of the container (i.e., the ocean carrier)

___________________

1 The chassis providing members of IICL are TRAC Intermodal, Flexi-Van Leasing, LLC, Direct ChassisLink Inc., and Triton International Limited.

BOX 3-1

Example Permutations of BCO Haulage Arrangements and Conflicts That Can Arise Among Transportation Providers

Ocean Carrier Haulage (CH): The BCO chooses a foreign port-to-door movement. The overseas, domestic rail (if applicable), and drayage services are coordinated and paid for by the ocean carrier under a contract with the BCO for a negotiated delivered price. The motor carrier is paid by the ocean carrier. If the motor carrier cannot supply its own chassis, it will be required by its contract with the ocean carrier to use a chassis from an IEP designated by the ocean carrier. Large BCOs may be able to nominate a preferred list of motor carriers to provide the drayage service as part of the negotiated bundled price. A potential source of conflict is that the motor carrier may encounter problems locating a chassis from the designated IEP; however, as a contractor to the ocean carrier, the motor carrier should be fully aware of the ocean carrier’s IEP requirements.

Merchant Haulage (MH): The BCO chooses a foreign port to U.S. port or inland rail terminal movement but not to the final destination. The overseas and domestic rail (if applicable) services are coordinated and paid for by the ocean carrier under a contract with the BCO for a negotiated door-to-terminal price. The BCO controls the final leg from the named seaport or rail terminal to the final destination. The BCO selects the motor carrier, which may source the chassis from an IEP or use its own chassis. A potential source of conflict is that the motor carrier may object to practices that favor the use of the ocean carrier’s partner IEP, including (1) direct pre-mounting of the container onto the partner IEP’s staged chassis (i.e., at “wheeled” terminals) and (2) billing practices at interoperable chassis pools that assign invoicing IEPs to the motor carrier based on the container being moved and its owner’s (i.e., ocean carrier) partner IEP. In the case of pre-mounting, the motor carrier may need to request that the container be flipped to the carrier’s preferred chassis for a fee and with time spent waiting.

Hybrids of Carrier and Merchant Haulage (CH/MH): The BCO chooses a foreign port to U.S. port or inland rail terminal movement but not to the final destination. The overseas and domestic rail (if applicable) services are coordinated by the ocean carrier under a contract for a negotiated price. In this case, however, the negotiated price includes chassis provisioning by the ocean carrier, even as the BCO retains the right to select the motor carrier. A potential source of conflict is that the BCO’s selected motor carrier may encounter problems locating a chassis from the ocean carrier’s designated IEP.

and not by the motor carrier. IICL maintains that such a billing policy is intended to facilitate the invoicing process and ensure that contributing IEPs can recoup their investments in chassis supplied to the pool in quantities sufficient to meet the needs of their partner ocean carriers. IICL emphasized that a motor carrier that uses such a pool can select a chassis from any IEP’s contributed supply. Choice is limited only in the sense that the motor carrier using the pool cannot select the invoicing IEP, and a motor carrier providing merchant haulage is free to use its own chassis or chassis from a proprietary pool unless the haulage agreement assigns chassis sourcing to the ocean carrier.

In their written comments to the committee, motor carriers and their trade association, the American Trucking Associations’ Intermodal Motor Carriers Conference, raised concerns about the pernicious effects of such billing rules that apply to interoperable pools. Some motor carriers maintained that the box rules are not simply a billing method but a means for interfering with the competitive process as motor carriers providing MH are prevented from selecting a preferred IEP for billing. Moreover, they complained that the motor carrier is obligated to pay that IEP’s rental rate with no room for negotiation.

With regard to hybrid haulage agreements (i.e., agreements other than carrier haulage) where the ocean carrier can source the chassis, the motor carriers raised concerns about the operational problems that ensue. In particular, they complained that their drivers must spend time and fuel searching for a chassis from the fleets of the designated IEP, and if they cannot secure one, they risk container demurrage charges by terminal operators or denial of reimbursement by the ocean carrier if an unauthorized chassis is used. Furthermore, they complained about the operational issues associated with drivers having to deliver a container for one ocean carrier, backtrack to return the chassis, and then drive to a different location to get another chassis to service a different ocean carrier (i.e., “chassis splits”). They stated that drivers may be required to return the bare chassis to a drop location that serves the IEP’s or pool’s repositioning needs and that this is time-consuming for the driver and inconvenient for the motor carrier.

However, the study committee was not able to determine through its discussions with motor carriers the frequency with which such operational problems arise in relation to total drayage moves. Furthermore, it was not clear whether motor carriers experience similar issues when fulfilling their negotiated agreements with ocean carriers for carrier haulage, which presumably could lead to chassis splits depending on the mix of CH and MH activity. In the absence of such information, including data about the preponderance of CH versus MH activity, the committee cannot judge whether the reported operational issues are infrequent irritants in

an otherwise responsive chassis procurement system or significant issues requiring intervention.

More evidently problematic are the concerns raised by motor carriers about chassis sourcing practices at terminals that have wheeled ramps where containers are pre-mounted on chassis. For motor carriers with MH agreements with BCOs that give them responsibility to choose the chassis, the practice of pre-mounting containers on a chassis staged by the ocean carrier’s partner IEP can render such choice meaningless. Terminal operators with wheeled ramps noted the operational advantage of this practice by requiring fewer container lifts and faster removal of containers to make room for inbound volumes. Motor carriers, however, complained that operators of wheeled terminals may not know if the container is being moved under carrier or merchant haulage but will nevertheless mount it on the chassis of the IEP partnered with its ocean carrier. The motor carrier is thus obligated to pay the IEP’s rental fee or ask the terminal operator to “flip” the container to its preferred chassis. While motor carriers may choose to request a flip, including for reasons related to ensuring safe, high-quality equipment, the process takes time and may involve a fee because wheeled facilities may have a limited supply of lifting equipment.

Motor carriers raised concern that ocean carriers may be using wheeled terminals to funnel business to their partner IEP for volume discounts that lower the ocean carrier’s own chassis rental rates. Motor carriers also noted that in serving wheeled facilities, they are discouraged from using their own chassis for pre-mounting, because the equipment would need to be staged in advance of the next inbound train, making it unavailable for other moves.

Ocean carriers, in their comments to the committee through the Ocean Carrier Equipment Management Association (OCEMA), stated that their chassis sourcing arrangements with IEPs complement other chassis sourcing practices while supporting the capacity of the IEPs to make large investments in the number and placement of chassis needed to handle the volume from their containerships and partner railroads. As a solution to some of the operational concerns raised by motor carriers (i.e., chassis splits and time and fuel spent searching for equipment), OCEMA expressed a strong preference for chassis provisioning through interoperable pools. That preference, of course, would be consistent with the ocean carrier’s interest in maintaining their existing business arrangements with IEPs.

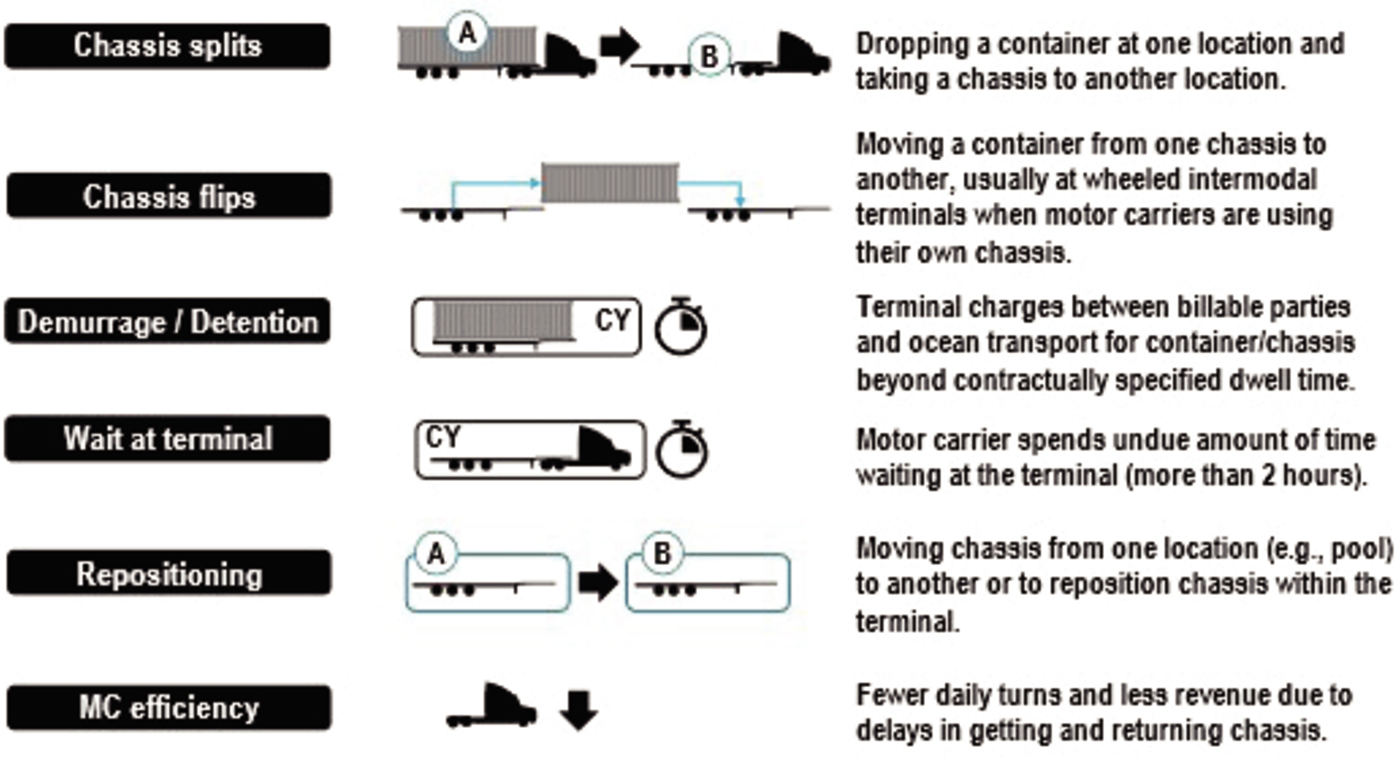

Figure 3-1 illustrates, among other things, why motor carriers are most concerned with these operational issues of the chassis provisioning system, as it indicates that they can bear costs across all these issues. While all stakeholders can incur costs when supplying their services, ultimately, BCOs and U.S. consumers incur all these costs as they can become embedded into the charges for transportation services. Moreover, as some of these operational issues also entail extra time and extra travel, they also have an

NOTE: CY = container yard; MC = motor carrier.

SOURCE: Adapted from Rodrigue, 2024.

impact on the public at large in the form of additional pollution and possibly congestion.

Chassis Quality and Condition

Issues pertaining to chassis quality and condition, or “roadability,” were raised by many of the consulted stakeholders, but primarily motor carriers. As would be expected, the motor carriers emphasized the importance of ensuring roadworthy chassis for safe and reliable service and noted that they experience delays and additional fuel costs when a chassis breaks down and they incur fines when faulty chassis are cited for safety violations by law enforcement. They explained to the committee that it is usually the responsibility of the driver to search for satisfactory equipment at terminals and that these searches can cost the driver time and sometimes prove futile. Difficulties finding acceptable chassis were cited for the chassis maintained by IEPs and by interoperable pools. Moreover, the motor carriers reported that chassis deficiencies identified at roadability checks at terminal exits can add further to the delay encountered by drivers, as they must wait for the needed repair or search again for an acceptable replacement and wait for the container to be flipped to it. In commenting on wheeled terminals, motor carriers questioned whether the pre-staged chassis are routinely

inspected before a container is mounted. They complained that drivers who identify a deficiency on a pre-mounted chassis will need to wait for the container to be flipped to another chassis.

Another issue raised by motor carriers is the expectation that upon returning a chassis the driver should inspect its condition and report deficiencies to the IEP. It was noted that drivers may be pressed for time and possibly reluctant to report a problem should the IEP claim that the driver and motor carrier are at fault. The incentives under these circumstances may be for the driver to not thoroughly inspect the chassis and report problems, which can increase the prevalence of faulty chassis stored at the depot, creating more challenges for other drivers trying to find an acceptable chassis. The motor carriers also reported that chassis at terminals and depots are sometimes stacked for storage, which can cause damage to the equipment.

Motor carriers explained that an important reason for owning their own chassis is to have more direct control over maintenance and repair, as well as the capacity to add safety features such as radial tires, antilock brakes, and LED lights. The IEPs, through the IICL and in their own comments, maintained that their industry spends hundreds of millions of dollars per year on chassis maintenance and repair. They also reported that they have invested substantial sums in new, refurbished, and upgraded assets. Citing chassis quality and condition as a key interest, the IEPs objected to proposals that would mandate their participation in interoperable pools,2 whereas OCs expressed a preference for such pools. A cited reason for opposing mandated pooling is that this would remove the direct connections between them and their customer that incentivize innovation and investments in equipment with advanced features. The IEPs maintain that these links also hold them directly accountable for chassis condition. They raised concerns about not having control over the maintenance and repair of the equipment they contribute to interoperable pools, as this responsibility then moves to the pool manager, even as the IEP is billed for the expense. In having their own proprietary fleets and depots, the IEPs contend that they can review their equipment more frequently, provide more systematic inspections, and better comply with requirements such as federal safety inspection obligations.

___________________

2 As mentioned in Chapter 2, Consolidated Chassis Management (CCM) announced that it would no longer provide chassis as part of the interoperable or gray pools in three Midwest cities as of May 1, 2024. In a recent Journal of Commerce article, one of the major criticisms of the CCM managed pools has been the poor quality of the chassis offered. See https://www.joc.com/article/cooperative-chassis-pools-folding-three-us-cities-amid-loss-business_20240429.html.

Information for Visibility and Forecasting

All of the stakeholders consulted—carriers, IEPs, pool managers, terminal operators, and BCOs—recognized the importance of information that can be used to align chassis supply with demand and enhance the operational fluidity and efficiency of drayage service. On this topic, the committee asked OCEMA to explain how ocean carriers send information on inbound containers to gateway ports and railroads serving inland markets. OCEMA reported that ocean carriers routinely send traffic data to the railroads, ports, chassis providers (IEPs and pool managers), and terminal operators. Depending on the recipient, this information may include expected volumes of containers at ports based on container number, size, and weight with estimated times of arrival by week for volumes destined for a port’s regional markets and for inland rail destinations. It was noted that some ocean carriers will generally notify railroads about anticipated weekly imports for a future period of time, such as 2 to 3 weeks out, so that they can allocate enough rail cars and have them prepositioned.

OCEMA reported that railroads, in turn, will typically communicate with regional chassis providers regarding their chassis needs based on anticipated inbound train arrivals for a period of 24 to 48 hours out. OCEMA reported that the information conveyed to chassis providers can differ by ocean carrier. Some may provide IEPs and pool managers with a 6-week forecast, updated biweekly, of inbound and outbound flows. Others may provide them with 1-, 2-, or 3-week forecasts for specific rail terminal and depot facilities. Depending on the structure of the chassis markets in the region, the forecasts may be sent to pool managers or to IEPs directly.

IICL confirmed that ocean carriers provide forecasting information about a week in advance of a ship’s scheduled arrival at port. The forecasting information includes containers that will be delivered so that IEPs can “fleet” for the total number of containers delivered. It was not made clear, however, whether this volume information is differentiated for carrier and merchant haulage to facilitate the IEP’s staging of chassis. IICL also reported that railroads provide daily reports with information on the inventory and disposition of chassis at their terminals and on anticipated inbound and outbound container volumes 72 hours out. IICL noted that while such forecasting information could also be provided to the much larger number of motor carriers who collectively own many chassis, it is the IEPs and pool managers that have the large, dispersed chassis fleets that need to be staged. At wheeled rail facilities, the IEPs maintain that they size their fleets for all of the railroad’s inbound traffic and use volume information and experience for readying chassis at grounded and hybrid (grounded/wheeled) operations.

Motor carriers nevertheless reported that they also would benefit from more timely data on container arrivals to plan and prepare for their drayage

services, including data on expected carrier and merchant haulage volumes. The committee was told that container pickup and delivery orders are often received from terminals with short notice. In one inland market visited, the committee observed that motor carriers were receiving this information during the morning. As a result, drivers dispatched to retrieve grounded containers had to start the day by spending time locating an acceptable chassis from the proprietary fleet of the ocean carrier’s designated IEP. In this regard, motor carriers also complained about the lack of current information on chassis availability at the depots of IEPs and pools, causing drivers to search for chassis in multiple locations. Such visibility, the motor carriers maintained, would allow trucking companies to schedule appointments for container pick-up days before a ship arrives at the terminal.

Because BCO orders are the source of demand for container shipping, forecasts for container volumes that extend out over longer periods would require BCO involvement. In discussions with BCOs and OCEMA, this matter was not raised, but it would be important for longer-term chassis planning and investment. Committee members familiar with BCO operations are confident that large BCOs do share such information with the ocean carriers they use on a regular basis. If and how such information is passed along by BCOs and ocean carriers downstream to ports, terminal operators, railroads, and providers of intermodal equipment and drayage services is less clear but is likely to depend on the entity’s size, usual volumes handled, and involvement in partnership arrangements.

The committee was surprised that upstream stakeholders—BCOs, ocean carriers, and ports—did not cite opportunities for leveraging digital capabilities for logistical information-sharing portals and for capabilities like predictive analytics that could confer benefits up and down the supply chain by enhancing traffic flow visibility to facilitate service planning and scheduling. The committee is aware that at least one U.S. port, the Port of Los Angeles, has been using a proprietary platform to collect and synthesize supply chain data to support analyses and forecasts of incoming container volumes.3 Such systems are generally referred to as port community systems because they connect the IT systems of multiple members of the port community to exchange information and documentation on the movement of cargo through the port.4 In the case of Los Angeles, the information is conveyed in a single portal for access by major stakeholders in the supply chain—however, the degree to which it is available to, and used by,

___________________

3 See www.portoflosangeles.org/references/news_111716_ge_transportation. Also see The Digital Transformation of Ports, https://porteconomicsmanagement.org/pemp/contents/part2/digital-transformation.

4 Port-Community-System Conference, https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/68e8007a36a64995a1d299069ffd7852-0430012023/original/Port-Community-System-Conference-Edition.pdf.

downstream stakeholders was not mentioned by the intermodal carriers and chassis providers who briefed and submitted information to the committee. Port community systems appear to be the wave of future digitalization in the ocean container transport market and are likely to be in demand by BCOs and ocean carriers.

During its information-gathering and consultations, the committee became aware of other ongoing data-sharing initiatives that merit highlighting and are described in Box 3-2.

BOX 3-2

Ongoing Data-Sharing Initiatives

The Freight Logistics Optimization Works Program

The Freight Logistics Optimization Works (FLOW) programa is a partnership between the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) and industry participants that is collecting information to build an “integrated view” of the U.S. supply chain that will help improve resilience. Administered by the Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS) within USDOT, FLOW gathers purchase order information from domestic importers (BCOs), as this information ultimately drives the demand for the logistical services of the different transportation modes. From the other industry participants (i.e., ocean carriers, ports, terminals, railways, and drayage providers), FLOW collects data about logistics supply, demand, and throughput. The data collected by BTS is anonymized, divided into regions, and aggregated, before participants are allowed to view the information.b The hope is that the collected data will provide visibility beyond the scope of a single company and help participants forecast how current volumes and throughput might fare against any changes in future demand to mitigate unexpected delays.c

International Convention on Facilitation of International Maritime Traffic

Since 2019, the International Convention on Facilitation of International Maritime Traffic (FAL Convention) has mandated the electronic data exchange of FAL declarations between ships and ports to help facilitate international trade.d Beginning in January 2024, the FAL Convention mandated the use of a “single window” for data exchange, where all the information required by public authorities for the arrival, stay, and departure of ships, persons, and cargo is submitted via a single portal, without duplication.e

The Maritime Transportation Data Initiative

In December 2021, Commissioner Bentzel of the Federal Maritime Commission (FMC) started the Maritime Transportation Data Initiative (MTDI) to identify data constraints impeding the flow of ocean cargo and adding to U.S. supply chain inefficiencies. The three objectives of the MTDI were to document the existing maritime data elements and metrics used, how the data are transmitted, and the protocols used for data access; identify any key gaps; and develop recommendations for common data standards and access policies and practices.f

SUMMARY ASSESSMENT

Because only a handful of BCOs were consulted for the study, it is not possible to gauge how BCOs in general view the current system for provisioning chassis and its variants across U.S. drayage markets. Of course, because BCOs are the customers of the intermodal container transportation system, their views about the system must be well understood when contemplating policies or interventions to affect chassis provisioning practices. BCOs, which include importers and exporters, will not always be versed on the

FMC Commissioner Bentzel released a final report in April 2023 that recommended the establishment of the Maritime Transportation Data System (MTDS), which would create a system or process for capturing information on planned ocean carrier voyages and vessel transits, including real-time position estimation of arrival. The MTDS also would call for the harmonization of available data so that ocean carrier vessel operations and arrivals, intermodal rail arrivals and departures, and information related to the access and restrictions into and out of both marine and rail facilities would be publicly accessible online. Finally, the final report (through the establishment of MTDS) recommended that information about the status of a container in transit on an intermodal rail carrier or in the custody of a marine terminal be made available to the shipper or their agents that are “in privity of contract with ocean and intermodal rail carriers.”g

In August 2023, FMC released a Request for Information seeking public comment on two sets of questions related to maritime data transmission, accessibility, and accuracy. The first set of questions was aimed at intermodal transportation service providers, while the second set was directed at importers and exporters. The comments received to the questions would be used to supplement the information received during the public meetings of the MTDI.h

In April 2024, FMC released a second Request for Information seeking public comment on questions related to maritime data accuracy with a focus on information related to containers moving through marine terminals. FMC is seeking comments about the data elements that are communicated between intermodal transportation service providers and importers and exporters and, more specifically, how changes to these data elements are communicated or miscommunicated throughout the transportation process.i

__________________

a https://www.transportation.gov/freight-infrastructure-and-policy/flow.

b https://www.bts.gov/flow/faqs.

c https://www.transportation.gov/mission/office-secretary/office-policy/freight/flow/freight-logistics-optimization-works.

d A list of declarations (e.g., cargo, crew, and vessel details) for a ship’s arrival and departure is found here: https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Facilitation/Pages/DeclarationsCertificates-default.aspx.

e https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/MediaCentre/HotTopics/Documents/FAL.5-Circ.42-Rev.3en.pdf.

f https://fmc2.fmc.gov/fmc-maritime-transportation-data-initiative.

g https://www.fmc.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/MTDIReportandViews.pdf.

details of the chassis provisioning system and its features, but they will take notice when major service disruptions occur as happened in 2021 and 2022.

Indeed, several of the BCOs and freight forwarders that met with the committee expressed concerns about the functioning of the system for providing chassis. Keeping in mind that the committee could only meet with a limited number of BCOs, those who did raise concerns commented about containers not being delivered in a timely fashion and demurrage charges being passed along to them when motor carriers failed to obtain a chassis in a timely manner from an ocean carrier’s partner IEP. A freight forwarder advocated for railroads to invest more in container handling and lifting equipment to allow them to move away from wheeled facilities in favor of grounded operations that are more amenable to chassis choice, including motor carriers using their own chassis. Notably, some exporters of agricultural commodities reported that bare chassis are inconsistently available to move their loaded containers to rail terminals. They complained about the lack of forecasting for chassis needs to support agricultural exports, as most forecasting focuses on the chassis that will be required for imported containers. These exporters joined motor carriers in complaining about shortages of chassis in working order at the depots of the ocean carrier’s designated IEP.

Apart from organizing and synthesizing these comments, the committee is not able to reach conclusions about which, if any, of the practices employed for chassis provisioning across the country’s varied intermodal markets deserve highlighting as preferable for BCOs and the public, either in general or in drayage markets having certain characteristics. Interoperable pools, which have been successful in some markets and not others, can have the advantage of simplifying chassis sourcing to reduce excess driving and increase chassis availability through portfolio effects; however, they can introduce billing complexities and in their current incarnation, possibly disincentives for participating IEPs to contribute high-quality equipment. Chassis sourcing by ocean carriers in carrier haulage agreements with BCOS as well as some merchant haulage agreements must have some compensating value to BCOs or they would not agree to these terms but would instead source their own chassis.

At the same time, certain practices, such as wheeled operations and box rule billing at interoperable pools, would seem to favor the IEPs and ocean carriers at the expense of BCOs that have hired motor carriers for merchant haulage and chassis sourcing. The trends for chassis provisioning, as will be discussed in Chapter 4, appear to be toward more chassis ownership and long-term leasing by motor carriers, which suggests that BCOs are seeing advantages to this sourcing approach and the market is responding as one would expect of a healthy, dynamic system. A movement toward a single approach to chassis sourcing, however, does not seem to be likely anytime

soon, not only because of the large investments in equipment that have been made by IEPs but also because of the heterogeneity of the country’s intermodal markets and diverse needs and preferences of the BCOs.

In the committee’s view, an emphasis of public policy should be on ensuring that the chassis provisioning system, like the larger intermodal shipping enterprise that it supports, is well positioned to meet the varied interests of the BCOs across the diverse intermodal markets where they operate, all while keeping the general public interest in mind. The study’s statement of task calls on the committee to evaluate the incentives for employing efficiency-enhancing communications, information sharing, and knowledge management practices across chassis provisioning models. If there was any consensus among the intermodal carriers, chassis providers, BCOs, ports, terminal operators, and other stakeholders consulted during the study it is about the importance of such data sharing and communications for operational efficiencies and planning by the downstream providers of intermodal transportation equipment and drayage services. Recent initiatives such as FLOW, the FAL Convention, and Commissioner Bentzel’s MTDI hold promise for strengthening supply chain information sharing.

In addition, the committee noted that stakeholders had mixed comments about the quality and condition of the chassis fleet as influenced by the specific features and practices of the provisioning system. Commenters pointed to market incentives for chassis providers to focus on equipment condition and quality, but also to provisioning practices that may dilute this focus and to worrisome accounts of deficient equipment being tendered. Given the imperative of road safety, one can make a strong case that this is one area where reliance on a dynamic chassis provisioning system that responds to BCO interests may not be enough to meet public interests. The next chapter takes a closer look at how chassis safety is overseen and regulated by the federal government and includes a review of federal data on the performance of chassis in roadside safety inspections.

This page intentionally left blank.