Developing a Guide for On-Bridge Stormwater Treatment Practices (2024)

Chapter: Appendix A: Task 1a Memorandum: Literature Review of Stormwater Treatment Processes and Treatment Options

CONTENTS

2. STORMWATER CHARACTERIZATION AND TREATMENT PROCESSES FOR TARGET POLLUTANTS

Prevalence and Speciation of Copper and Zinc in Bridge Deck Runoff

Review of Candidate Treatment Processes

Summary of Inert Media Filtration Processes

Summary of Media Sorption Processes

Summary and Practical Considerations

3. MEDIA CHARACTERISTICS FOR EFFECTIVE REMOVAL OF COPPER AND ZINC IN THE BRIDGE DECK ENVIRONMENT

Criteria for Stormwater Treatment Media Selection

Effective Copper and Zinc Removal

Co-Benefits for Other Pollutants of Concern

Physical and Mechanical Strength

Commercially Availability from Multiple Suppliers

Media Replacement and Disposal

4. REVIEW OF TESTED FILTRATION MEDIA BLENDS

Literature Review and Assessment Approach

Western Washington Media Studies

Boeing Santa Susana Field Laboratory - Media Testing Study

Granular Ferric Oxide Field Tests

Washington DOT Media Filter Drain

TAPE-Approved Manufactured Systems

Media Filter Category from International Stormwater BMP Database

5. MEDIA RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FURTHER TESTING

Narrative Evaluation based on Criteria

1. Introduction

This memorandum (memo) summarizes the results of the literature review that was conducted for Task 1a of NCHRP Project 25-61. The overall goal of the project is to develop guidelines for implementing effective and practical stormwater treatment systems to remove stormwater pollutants from highway runoff within the physical constraints of the bridge environment.

This literature review was completed to provide a better understanding of target stormwater pollutant behavior and presence in highway runoff, treatment processes for target pollutants, and filtration media that effectively removes or eliminates the toxicity This information will be used to help develop and test stormwater treatment devices and filtration media during Task 3. of target pollutants (hereto referred to as pollutant removal effectiveness) from highway runoff. One of the primary goals of this literature review is to develop sufficient understanding of stormwater pollutants and removal and toxicity reduction processes to propose a filtration media for further testing in Task 3. The proposed media based upon this literature review is described in Section 5.

A parallel effort under Tack 1b includes assessment of structural and hydraulic configurations of treatment devices and tradeoffs between treatment flow rates, capture efficiency (i.e., the fraction of long-term runoff volume treated by the device), and pollutant removal effectiveness. The hydrology and hydraulic topics will not be directly considered in this memo.

Prior to conducting this literature review, the project team developed the following working assumptions regarding treatment alternatives and filtration media:

- Copper and zinc are the target pollutants, as described in the NCHRP Project 25-61 Request for Proposal. Toxic organic compounds (such as 6PPD-quinone) are not considered target pollutants, but these are likely addressed by many of the same processes that remove dissolved copper and zinc.

- Due to presence of target pollutants in both dissolved and particulate-bound forms, both physical filtration and sorption are likely needed to effectively remove target pollutants from runoff. This narrows the scope of review to focus on media filtration options. Justification for this assumption is provided.

- Because water quality targets vary by location, the pollutant removal effectiveness of filtration media should be compared to removal effectiveness standards, not specific water quality targets. As many states utilize or accept stormwater best management practices (BMPs) that are approved by the Washington State Department of Ecology Technology Assessment Protocol – Ecology (TAPE), enhanced (i.e., dissolved metals) removal standards have been used as pollutant removal effectiveness benchmarks in this literature review (Washington Department of Ecology, 2018).

- Because of physical space constraints in the bridge deck environment, higher media flow rates will allow treatment devices to treat a greater portion of long-term runoff in a small footprint. While the tradeoffs between media flowrates and long-term capture efficiency on overall performance will be evaluated more specifically in Task 1b, our review of candidate media blends was weighted toward those with demonstrated performance at higher media flowrates as this is an important attribute for bridges.

- Media selection will focus on candidate media blends with existing literature and track records, rather than on individual media components or new blends formed from individual components.

The sections of this memorandum are organized as follows:

- Section 2 characterizes the forms and abundance of zinc and copper in highway stormwater runoff. This section builds on this characterization to evaluate and identify treatment processes that are effective in removing these pollutants.

- Section 3 identifies and summarizes the filtration media characteristics needed to meet project goals, such as pollutant removal effectiveness, hydraulics (e.g., treatment flow rate), durability, and replacement/disposal.

- Section 4 reviews the effectiveness of blended filter media mixes based on studies that have investigated copper and zinc removal with real stormwater. This includes assessments of pollutant removal effectiveness as well as filtration hydraulics (e.g., treatment flow rate), and any information about clogging lifespan that is available. This section synthesizes the aspects of these studies that are relevant to this project.

- Section 5 includes an evaluation of candidate media blends based on the desired characteristics in Section 3 and presents the research team’s recommendation for a filtration media blend and component characteristics that could be included in Phase 2 of this project.

2. Stormwater Characterization and Treatment Processes for Target Pollutants

This section provides a review of highway runoff stormwater characterization data and identifies the treatment processes that are expected to be effective for target pollutants. For this project, copper and zinc are the target pollutants. Additional information on this topic is available in prior NCHRP reports including NCHRP Report 767 (National Academies, 2014a).

Speciation of Copper and Zinc

The fate and transport of metals in natural surface waters is highly dependent on the properties of the particular metal, the solution chemistry of the water (i.e., pH, ionic strength, redox state, and presence of biotic, organic and inorganic ligands) and interactions with resident particulate matter in the system. Figure 1 provides a schematic of the different potential reactions that affect metal ion speciation in water.

Metal concentrations are commonly separated into total and dissolved phases. One can further discriminate between particulate (total – dissolved) and dissolved. The particulate phase as it is defined consists of those boxes in green in Figure 1. Although colloidal metal species are, in fact, particulate, their diameter is less than the pore size (about 0.45 μm) of the filters used by analytical laboratories to distinguish between the particulate and dissolved phases. Consequently, the value reported for dissolved metal concentration includes some fraction of colloidally bound metals. Sorption of trace elements such as metals to colloidal matter, including nanoparticles, can have a significant impact on metal ion mobility, removal, and aquatic toxicity. Among metals in the true dissolved phase are both free ions as well as metals adsorbed to organic and inorganic ligands. The metals adsorbed to organic and inorganic ligands are generally less biologically available.

Primary Particulate Fraction (>15 micron)

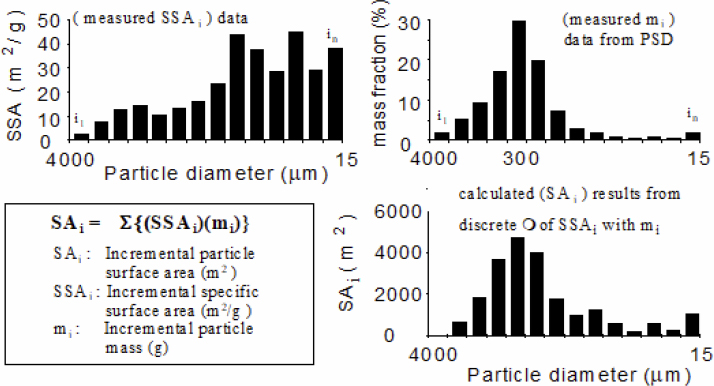

Within the particulate fraction, water quality parameters that are important from a treatment perspective include mass loading (i.e., the mass of pollutants contained in influent), particle size distribution (PSD), specific gravity, specific surface area (SSA, the surface area per unit mass), and total surface area (SA). Among larger particulates, a typical relationship between PSD, SSA and SA is illustrated in Figure 2 for particles larger than 15 µm in diameter (Sansalone and Tribouillard 1999).

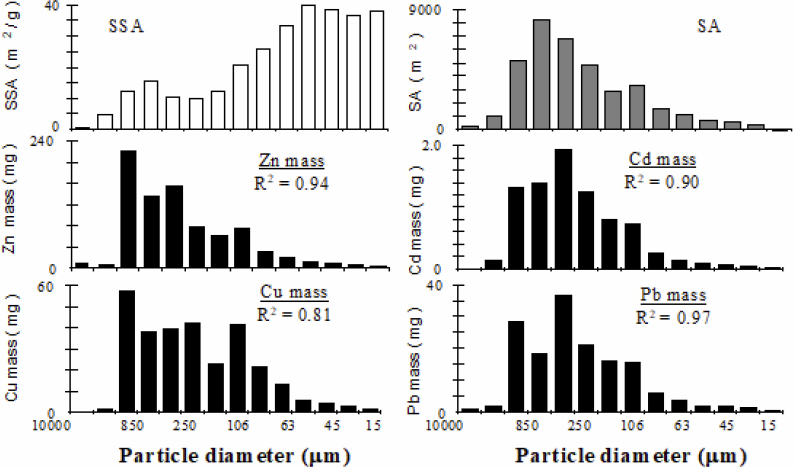

SSA and SA data in Figure 2 demonstrate that although SSA does increase with decreasing particle diameter (by definition), the largest percentage of total SA is associated with particles in the 250 - 350 µm range. Additionally, the increase in SSA with decreasing particle size is not monotonically increasing as would be expected for spherical particles of constant specific gravity. Although SSA increases with decreasing particle diameter, calculations using the assumption of solid spherical particles grossly underestimate actual SSA values shown, likely because particles are irregularly shaped and can contain a significant volume of internal pores. Although SSA does increase with decreasing particles diameter, the distribution of metal mass is correlated to the total SA of particles and not SSA, as presented in Figure 3. At least among particles larger than 15 µm, these data indicate that most of the metal mass attached to particles is associated with particles whose diameters are sufficiently large that they can likely be removed through filtration.

Note that some particles in the ranges in Figure 2 and Figure 3 may not be transported through a stormwater conveyance system, so may not be reflected in stormwater inflow to a BMP.

Smaller Particles (<15 um) and Dissolved Phase

Among finer particulates and dissolved phase pollutants, water chemistry parameters such as pH, metal ion concentration, the presence of other reactive ligands and metals, ionic strength, and redox potential, as well as the type and prevalence of suspended solids dictate metal ion speciation and partitioning within the water column through sorption, complexation, and oxidation/reduction processes. These processes impact the extent and rates of interaction with particulate matter and the bioavailability of metals. In general, copper and zinc present as free ions are most bioavailable and most toxic to aquatic organisms so reducing the toxicity of copper and zinc can be achieved by removal or by reducing the fraction present as free ions.

Research by Nason et al. (2012) quantified the speciation of copper in highway runoff. They report on the characterization of copper binding ligands and copper speciation in composite samples of highway stormwater runoff collected at four sites in Oregon. Although the concentration and strength of copper binding ligands in stormwater varied considerable between sites and storms, the vast majority (>99.9%) of the total dissolved copper in composite samples was complexed by organic ligands in stormwater. Although total dissolved copper concentrations ranged from 2 to 20 μg/L, the analytically determined free ionic copper concentrations did not exceed 10−10 M (6.3 ng/L) in any of the fully characterized samples, suggesting that much of the dissolved copper in highway stormwater is colloidally bound and not bioavailable. While these data suggest that most of the dissolved copper in some stormwater runoff may be present in less toxic forms, the form of copper can change when stormwater enters receiving waters, so runoff could have increased toxicity in receiving waters. This study did not quantify speciation for zinc and no similar studies for zinc were found. Other studies have shown that ionic zinc typically has a lower affinity for dissolved organic matter than dissolved copper, so it is likely that dissolved zinc has a higher fraction in the ionic phase than dissolved copper in most stormwater (National Academies, 2014a).

Because copper and zinc are present in a broad range of partitioning and speciation, removal of multiple species will likely be required to achieve desirable water quality outcomes in terms of reducing total and dissolved metals concentrations and potentially reducing aquatic toxicity. The challenge then is to identify the most effective and prevalent removal mechanisms for each phase of copper and zinc. The expectation is that metals associated with suspended particles can be effectively removed by sedimentation and media filtration. On the other hand, free ionic metals and those complexed with organic and inorganic ligands may also be effectively removed via sorptive media. Colloidal materials are likely to be the most difficult to remove since they are too small to be removed via filtration but also not able to be as readily removed via sorption. Media that provides colloidal materials for free metals sorption may also reduce toxicity even if not removing the colloidally bound metals.

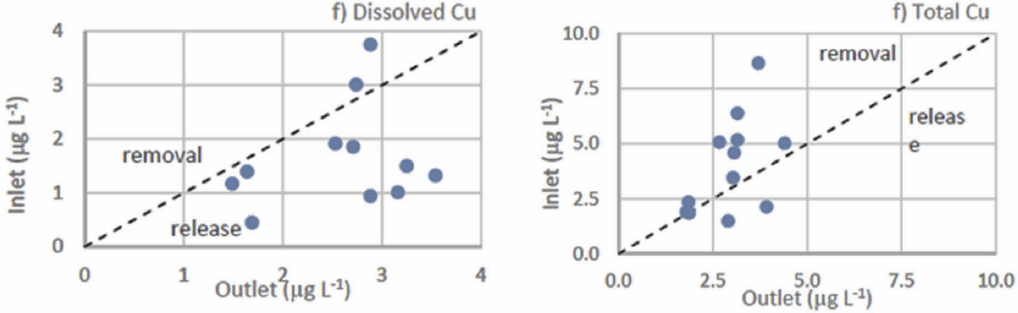

Prevalence and Speciation of Copper and Zinc in Bridge Deck Runoff

Due to the challenge of sampling bridge deck runoff, limited data are available characterizing pollutant concentrations in bridge deck runoff. In highway runoff, copper and zinc are present in moderate concentrations as presented in Table 1. These data represent influent concentrations for stormwater BMPs treating highway runoff and were accessed using the International Stormwater BMP Database DOT Portal (https://dot.bmpdatabase.org/). These data show that dissolved (passing 0.45 µm filter) typically account for around one-third to one-half of total copper and total zinc.

Table 1. Summary of BMP influent copper and zinc concentrations from the International Stormwater BMP Database DOT Portal

| Statistic | Total Copper (μg/L) | Dissolved Copper (μg/L) | Total Zinc (μg/L) | Dissolved Zinc (μg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| 10th Percentile | 5.0 | 2.2 | 23.3 | 8.9 |

| 25th Percentile | 9.0 | 3.9 | 41.5 | 14.5 |

| 50th Percentile | 17.1 | 7.4 | 88.9 | 27.7 |

| 75th Percentile | 34.0 | 14.5 | 190 | 61.0 |

| 90th Percentile | 62.0 | 25.5 | 350 | 125 |

| Maximum | 800 | 620 | 2,100 | 1,500 |

Bridges often have higher traffic on average than typical highway sites. Additionally, the conditions on bridge decks, specifically higher wind velocities that could resuspend finer particulates, could result in reduced pollutant concentrations in bridge deck runoff compared to typical highway runoff. Several studies have attempted to assess whether differences exist between pollutant concentrations in runoff from bridge decks compared to more typical roadways.

TxDOT funded a study of this issue in 2005 (Malina et al., 2005). The study compared pollutant concentrations in runoff collected from a bridge deck to those in runoff collected from the bridge approach on the same highways. The results of that monitoring effort are presented in Table 2. The average concentrations of all the constituents observed in the runoff from the bridge deck and approach highway at the Loop 360 site in Austin, the Farm to Market (FM) 289 site in Lubbock and the FM 528 site in Houston are of the same order of magnitude with few exceptions. These data do not suggest any meaningful difference in pollutant concentrations in from bridge decks compared to roadways with similar traffic volumes.

Table 2 Mean and Median Concentrations of Constituents in Runoff from the Bridge and Approach Highway, at Three Sites in Texas

| Constituent | Units | Austin | Lubbock | Houston | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bridge | Road | Bridge | Road | Bridge | Road | ||

| Copper, Total | µg/L | 16.4 | 23.5 | 18.7 | 21.8 | 18.2 | 8.5 |

| Copper, Dissolved | µg/L | 4.2 | 6.5 | 7.6 | 8.9 | 11.9 | 4.9 |

| Zinc, Total | µg/L | 166.5 | 134.6 | 127.6 | 123.5 | 140.9 | 38.2 |

| Zinc, Dissolved | µg/L | 28.8 | 30.7 | 72.4 | 62.7 | 77.3 | 17.2 |

| Suspended Solids, Total | mg/L | 111.8 | 119.2 | 104.0 | 109.4 | 53.0 | 30.8 |

One important factor for pollutant concentrations in bridge deck runoff is likely the type and height of the guardrail. Bridges with relatively open guardrails would likely have lower pollutant concentrations due to material being resuspended by vehicle induced turbulence and higher wind speeds over water and blown off the bridge resulting. Many newer bridges have mostly solid concrete barriers 36 to 42 inches high, which could retain more pollutants on the bridge deck.

Another factor specifically affecting metal runoff concentrations is the type of bridge construction material. For instance, guardrails that are galvanized could be a substantial source of dissolved zinc in runoff compared to concrete guardrails. An unpublished study (known to the authors) of a bridge in the Houston, Texas, area with galvanized metal rails found zinc concentrations greater than 1,000 μg/L in rainwater dripping from the railing, which is much higher than the 10 to 100 μg/L range commonly observed in runoff. Researchers have also examined the concentrations of zinc in runoff galvanized roofing materials (Tobiason, 2004; Clark et al., 2008). As an example, Clark et al. (2008) reported concentrations of zinc in runoff at concentrations as high as 30 mg/L, much higher than the roughly 0.1 mg/L reported in Table 1.

There are good reasons to assume that concentrations of dissolved metals in bridge runoff would be strongly affected by site specific factors as well. For instance, many studies have documented a general relationship between average annual daily traffic (AADT) and pollutant concentrations (e.g., Kayhanian et al., 2003; National Academies, 2014b). Consequently, bridges with higher traffic (urban areas and interstates) would be expected to have higher concentrations of copper and zinc. In addition, surrounding land use is expected to influence runoff concentrations via aerial deposition, so that bridges in industrial or urban areas would be expected to have higher pollutant concentrations. Consequently, it is likely that urban bridges with high AADT would have the highest pollutant concentrations.

Review of Candidate Treatment Processes

There are several treatment processes that can be effective for removal of metals from stormwater depending on the form of the metal. There are also processes which can reduce the toxicity of metals released from media treatment without removing them from runoff. These processes include sedimentation or gravity separation, inert media filtration, sorption, and changes to metal speciation.

Some particle sizes can be separated by sedimentation with adequate settling time. However, due to space constraints, effective sedimentation for fine particulates is not compatible with treating runoff in the bridge deck environment, so sedimentation is not considered further as a significant potential treatment mechanism in this literature review.

Hydrodynamic separation may be more compatible with bridge deck space constraints. These systems can be effective for removal of coarse particles. However, analysis of HDS systems in the International BMP Database (Clary et al., 2020) showed very little removal of copper or zinc by these types of devices. At best, these systems showed 22% removal of total zinc, with an effluent quality of 62 μg/L. These systems showed less effect for total/dissolved copper and dissolved zinc.

Permeable friction coarse (PFC) is a potential candidate for bridge decks that has been considered as part of previous research on bridge deck runoff (National Academies, 2014b). This could complement other treatment by reducing influent loads and potentially prolonging clogging. However, the purpose of this project is specifically to review additional treatment mechanisms beyond PFC. Therefore, PFC is not considered further.

The particle sizes that are removed by gravity separation are also easily removed via filtration along with smaller particles. Therefore, sorptive media filtration is considered the most applicable approach for removing both particulate and dissolved copper and zinc from stormwater runoff in the bridge deck

environment. This treatment process also has the potential to impart changes in speciation that can reduce toxicity without changing overall metal mass. Additionally, sorptive media filtration can provide co-benefits for other pollutants beyond copper and zinc, including other heavy metals, total suspended solids (TSS), toxic organic compounds (e.g., polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, 6PPD-quinone), hydrocarbons, whole effluent toxicity, and nutrients.

Sorptive media filtration can be broken into the following separate treatment mechanisms, with some overlap between the two:

- Inert media filtration consisting of cake (surface) filtration and depth filtration whereby particles are removed primarily via physical mechanisms.

- Media sorption whereby pollutants are primarily removed via chemical mechanisms.

The following sections provide additional background on these two categories of filtration mechanisms.

Summary of Inert Media Filtration Processes

Inert media filtration consists of two primary unit processes: cake filtration and depth filtration. Cake filtration represents physical removal of particulates on the surface of filtration media when stormwater particulates are physically strained because they are larger than the pore spaces in filtration media (Figure 4). As the cake forms atop the filtration media, it can trap finer and finer particles, eventually becoming the limiting factor for filtration media flow rates and leading to clogging. To restore filtration flow rates, this cake either has to be periodically broken up or removed, or the filter itself replaced. Examples of cake filters include slow sand filters, fabric filters, and membrane filters.

Depth filters use coarser media which allow some or all of the particles to flow into the open pores of the media bed surface. Depth filtration is commonly used in processes like drinking water treatment since it reduces clogging and head loss while better utilizing the filtration capacity of the entire media bed. Particle removal in media filters with depth filtration is conventionally modeled as a combination of three attachment mechanisms, which are illustrated in Figure 5. These mechanisms include capture by sedimentation (particle is moving faster than the fluid due to gravity), interception (particle momentum causes collision), and diffusion (Brownian motion results in particle collision).

The classic depth filtration model consists of quantifying the removal associated with a single filter media particle and then integrating over the entire volume of the filter. This results in the classic formulation (Yao, et al. 1971):

Where:

Te = Trapping efficiency

ε = Filter porosity

α = Collision frequency

η = Attachment efficiency

dc = Characteristic diameter of the filter media particles

L = Filter thickness

This formulation has two major empirical factors: η and α. The first of these refers to the rate at which particles in the fluid strike a collector (i.e., media particle) in the filter. α represents the rate at which particles that strike the collector become attached and is function of physical and chemical characteristics of media particles and particulates in the fluid. Figure 6 shows removal versus filter depth assuming a media filter with about 90% solids removal at a depth of 18 inches, which is typical for Austin sand filters (Barrett, 2003, Clary et al. 2020). Figure 6 implies that depth filtration requires a substantial filter thickness for effective particle removal from stormwater, but also that there are diminishing returns with increased filter depth. This is confirmed by laboratory research indicating increased performance with increasing depth but also diminishing returns above a certain depth (e.g., Hatt et al., 2007).

There are several issues with the use of this model for analyzing performance of stormwater media filters. The model gives the same results for all events since it does not include information related to changes in PSD in the runoff and it does not account for changes in performance resulting from accumulation of particles within the filter. Perhaps the biggest shortcoming is that this conceptual model does not address particle removal via straining, which is generally avoided in heavily engineered systems (e.g., drinking water filtration) to reduce headloss. Straining is believed to be an important removal process when:

- Flow rates are low (<150 inches/hour) and solids flux is high.

- Ratio of particle size to media size is >0.2.

- Particles in the fluid have a diameter greater than 100 μm.

All of these are typically true in passive stormwater filtration systems. For example, sand filters used for stormwater treatment are slow sand filters with typical flow rates in the range of 1 to 6 inches per hour (City of Austin, 2021, Washington Department of Ecology, 2019), far less than the critical value for straining. Many of the particles in stormwater are relatively large; consequently, straining may account for between 50-80% of particle removal when the filter is clean (Barrett, 2009). As material accumulates on the surface even smaller particles would be subject to removal by straining, so that eventually straining would likely account for virtually all particle removal. Consequently, conventional mathematical formulations that described depth filtration performance are not likely relevant for stormwater treatment.

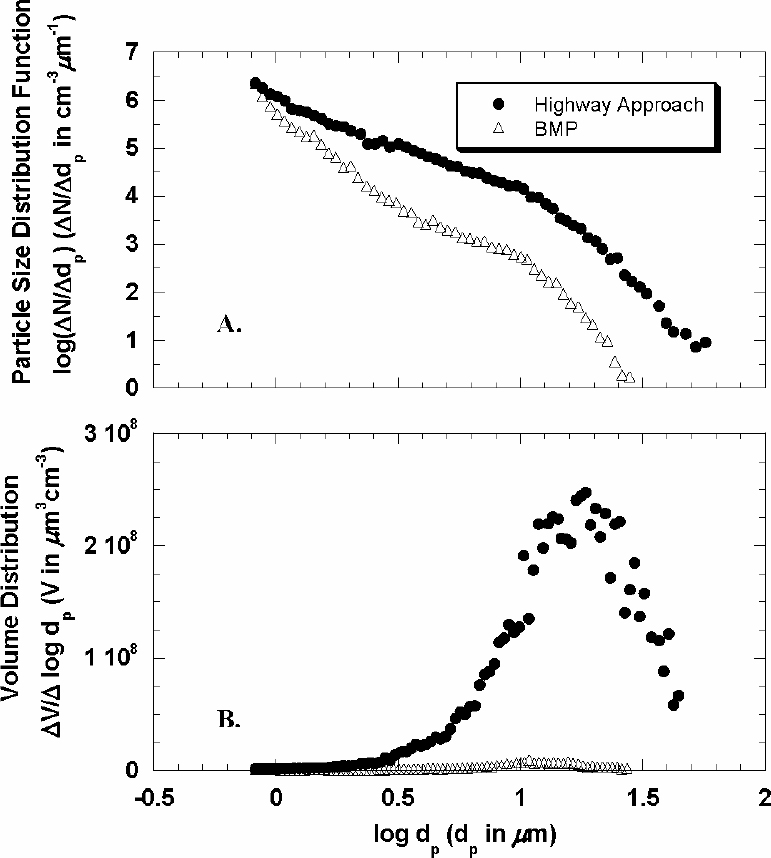

While classical depth filtration theory is not applicable, stormwater filtration is known to effectively remove fine particulates. Research completed in Austin, Texas as part of the previously described bridge deck runoff study (Malina et al., 2005) compared untreated stormwater samples from the Loop 360 to the same runoff after treatment through an Austin sand filter (Karamalegos, 2005). The PSD functions and volume distributions for these coupled samples are displayed in Figure 7. Between the inflow and outflow samples, the particle size function distributions shows an efficient removal of particles with a diameter larger than 1 µm (log dp > 0), and the distributions of total particle volumes illustrates a significant decrease in total particle volume for particles with a diameter larger than 2.5 µm (log dp > 0.4). Consequently, one can see that sand filtration can effectively remove all but the very smallest particles and could therefore remove the vast majority of copper and zinc associated with particles greater than 15 µm based on the work

by Sansalone and Tribouillard (1999) described previously. However, it is not clear whether stormwater filtration is an effective removal mechanism for particles smaller than 1 µm in diameter, including colloidal particles. Pollutants associated with these fine particulates are likely the hardest to remove from stormwater runoff and may pass through most filtration media, even when carefully designed and maintained.

Summary of Media Sorption Processes

Sorption is considered to be the primary removal mechanism of dissolved copper and zinc in media filters. Sorption is a physical and chemical process by which one substance becomes attached to another. For the purposes of this literature review, the following general definitions will be used:

- Absorption: the incorporation of a substance in one state into another substance of another state. For example, the process of a liquid of gas being absorbed by a solid.

- Ion exchange: the exchange of ions between two electrolytes or between an electrolyte solution and a complex. For example, the exchange of free zinc ions in solution onto a zeolite with ion exchange sites, resulting in the displacement of another ion previously occupying the location.

- Adsorption: the physical adherence or bonding of ions or molecules onto the surface of another phase. For example, the absorption of dissolved organic molecules onto granular activated carbon.

The process of absorption requires that a phase change in the substance from gas to liquid or from liquids to solids. The goal of this research is to remove dissolved metals from liquid runoff, so clearly no change in phase for the metals would occur. Consequently, absorption will not be discussed further.

Ion exchange is the process by which an ion in solution becomes sorbed to a solid phase material (i.e., sorptive media) with a local positively or negatively charged location (i.e., ion exchange site) simultaneously displacing another ion that previously occupied this ion exchange site (National Academies, 2014b). Depending on the media, heavy metal ion uptake preferences vary. Johnson et al. (2003) found that composition preference order for free ions in solution at the same concentrations was Cd>Zn>Pb>Cu>Cr>Fe for a peat-sand mix while for St. Cloud Zeolite the preference order was Zn>Cd>Pb>Cu>Cr>Fe. These data suggest that certain stormwater filtration media may be highly effective for removing free copper and zinc ions from runoff even in the presence of other competing free ions. In the presence of other ions at extremely high concentrations (e.g., sodium and magnesium derived from road salt), the sorption preference for ion exchange sites may be somewhat altered, however, good removal of free copper and zinc ions from stormwater runoff is achievable.

Ion exchange is a relatively rapid process that it is compatible with the short contact time present in high flow rate media filters. However, many ion exchange sites are in internal pores, especially for certain highly porous media (e.g., zeolites, granular activated carbon, biochar), so during storm events much of the ion exchange occurs on the surfaces of the particles where a more limited amount of ion exchange sites exist. It is thought that between storm events some portion of the initially exchanged ions may migrate into internal pores and attach to ion exchange sites there.

Adsorption is the primary process by which complexed dissolved metals are remove in filter beds. Based on the relatively low abundance of free ionic metal species in stormwater and greater abundance of complexed dissolved metal species, a media that provides adsorption is expected to be necessary to achieve TAPE standards. Recent developments in stormwater treatment (e.g., research summarized in Section 4 of this memorandum) indicate that removal of dissolved species through adsorption on engineered media can be an effective strategy depending on the strength of the bond between the metal and the organic and inorganic ligands. Metal adsorption onto natural and engineered media, such as sand, soils, granular activated carbon (GAC), and oxide-coated media, has been well-researched (Stumm 1992, National Academies of Sciences 2014a). Specific media have been proposed for adsorption of metals transported in stormwater. In addition to removing metal ions via sorption, most of these media are inherently able to provide some level of particle-bound metals treatment depending on physical quantities such as surface loading rate, geometry of the media system and the granulometry (size and gradation) of the media.

Sorption capacity (practically, the sum of ion exchange and adsorption) is not an inherent property of a material but depends on water chemistry as well. To determine the sorption capacity of a material a series of experiments are run at different metal concentrations to determine the amount sorbed to the material. At low concentrations the relationship between concentration and sorption capacity can often be approximated by a straight-line equation in the form of:

qe = KD Ce

Where:

qe represents the mass sorbed per mass of sorbent in mg/mg,

Ce is the equilibrium concentration of the metal ion in mg/L,

KD is the linear partitioning coefficient in L/kg.

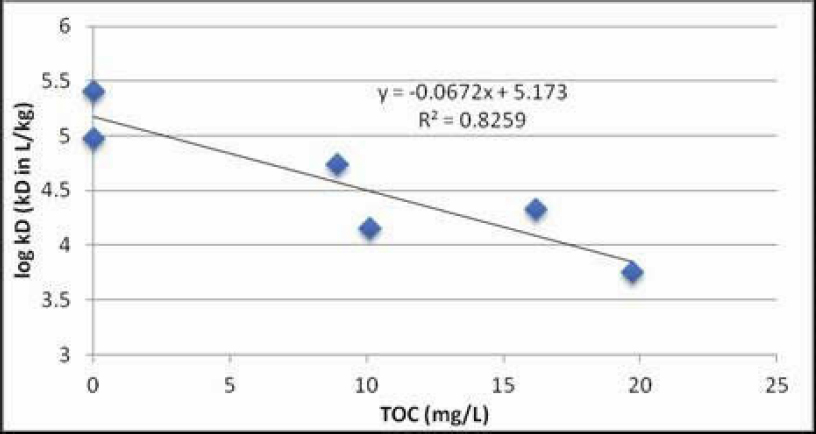

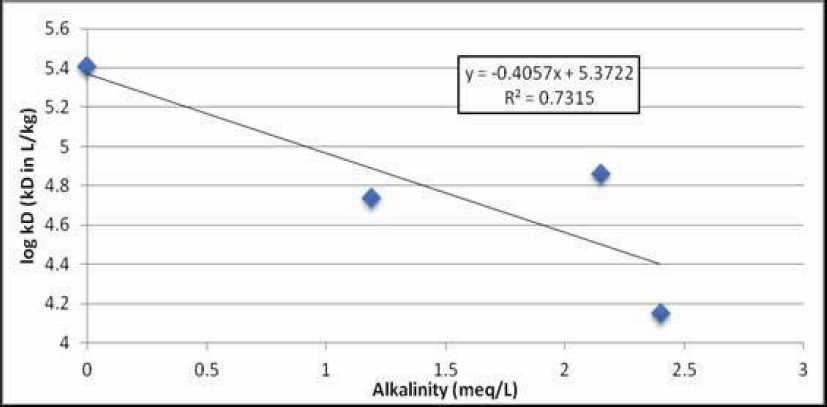

Sorption experiments are typically conducted for a range of solution concentrations, but they can also be conducted with the same target pollutant concentration but differing concentrations of other constituents such as organic and inorganic ligands to determine their impact on adsorption of target pollutants. The figures below from Barrett et al. (2013) demonstrate the impact of total organic carbon (TOC) (Figure 8) and alkalinity (Figure 9) on KD for the sorption of copper onto granular ferric oxide (GFO). Note that for both figures the y-axis is a log scale, so for each series of experiments a factor of 10 loss in sorptive capacity is observed over a range of TOC and alkalinity concentrations found in highway runoff. This suggests that in practice, metal removal performance for a given sorbent will vary by location and likely by storm due to changes in stormwater chemistry and the condition of the media from prior storms.

In addition to ion exchange and adsorption, copper and zinc can be chelated onto certain media, especially organic media. The “active” ingredient in organic matter are humic substances composed of high molecular weight humic acids to short chain lignan which form organo-metallic ligands that can chelate copper and zinc. This can both remove copper and zinc from solution and also reduce their toxicity even if they pass through the filter.

Summary and Practical Considerations

Stormwater characterization for metals is relatively complex and variable. On average, particulate-bound metals account for around two-thirds of metal mass in stormwater runoff. However, there is relatively high variability. Within the dissolved fraction, there are several different chemical species, each with different bioavailability and removal mechanisms. The speciation can vary from site to site and from storm to storm. In order to consistently meet TAPE enhanced treatment benchmarks, a BMP needs to address both total and dissolved metals, including potentially multiple species of dissolved metals.

Media filtration is believed to be the most compatible treatment technology for the target pollutants, treatment goals, and space constraints on bridge decks. Conventional settling requires too much space. Hydrodynamic separation could fit but does not achieve necessary levels of metals removal. In contrast, media filtration is a proven technology for both particulate-bound and dissolved species within relatively small footprints and has been shown to be effective at relatively high flow rates.

To balance particulate removal with media bed lifespan, a media filtration design that promotes depth filtration and straining more likely to have longer lifecycle than a design that promotes cake filtration. Additionally, the use of permeable friction course material could reduce influent sediment loads.

Removal of dissolved and colloidal metals requires some form of sorptive process, which can include ion exchange and/or adsorption. The relative role of each sorptive component can vary depending on influent characteristics, and different media materials provide different processes. A combination of media components providing different sorptive mechanisms appears to be desirable, as this provides a robust treatment system across variable influent characteristics.

3. Media Characteristics for Effective Removal of Copper and Zinc in the Bridge Deck Environment

Criteria for Stormwater Treatment Media Selection

Filtration media for removal of copper and zinc needs to be effective for removing these pollutants, but it should also meet other criteria to be effective. The following primary criteria should be met:

- Blended media should provide effective removal of copper and zinc across variable stormwater influent quality at flowrates needed to support feasible bridge deck designs. Specifically, blended media should meet TAPE standards (Washington State Department of Ecology, 2018) for enhanced treatment.

- Blended media should provide co-benefits for other common highway pollutants, such as removal of toxic organic compounds, nutrients, and reduction in whole effluent toxicity.

- Blended media should have adequate hydraulic properties to achieve high treatment flow rates and resist clogging.

- Materials should have adequate physical and mechanical strength to resist physical degradation.

- The materials and blends should be commercially available from multiple vendors to allow DOTs to specify materials without triggering sole-source procurement rules or policies.

- Media blends should be relatively simple to replace and allow disposal or use as non-toxic waste.

These criteria can likely be met by a range of media blends containing some combination of relatively coarse sand and sorptive media. The following subsections provide some details about for these criteria.

Cost and availability are notably missing from these criteria. Retrofitting a bridge for stormwater treatment, include engineering design and construction of BMPs is likely to be extremely expensive. Media replacement as part of operations and maintenance activities (O&M) is also likely to be expensive. In addition to these costs, construction and O&M activities on bridge decks likely require lane closures, adding cost and logistical concerns. Among these costs and logistical considerations, the cost of a small volume of stormwater filtration media is likely to be nearly irrelevant, so cost is not considered a primary criterion in this literature review.

Similarly, regional material availability is not considered a primary criterion. Given that stormwater treatment has been conducted on only a few bridges, and the fact that such treatment is not expected to be broadly required, it is unlikely that material volume requirements will be significant. Regionally available media are preferred but shipping small quantities of filtration long distances from a reputable supplier may be a preferred option from a quality control and therefore compliance perspective. While regional availability is not considered a primary criterion, general material specifications for the proposed media are included in Section 5 and could be provided to regional media suppliers.

Effective Copper and Zinc Removal

For the purposes of this review, TAPE standards for enhanced treatment are used as a benchmark for effective pollutant removal. Technologies meeting these requirements are approved for use under Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) permits which apply to many DOT roadways, especially those in urban areas. TAPE standards for enhanced treatment focus on removal of dissolved copper and zinc, however, they also require removal of TSS as required under TAPE basic standards. A full summary of relevant TAPE standards is presented in Table 3. Percent removal standards for TAPE apply to the 95% confidence interval of collected monitoring data.

Table 3. TAPE standards for basic and enhanced treatment

| Pollutant | Units | Influent Range | Removal Standard | TAPE Standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSS | mg/L | 20-100 | Effluent < 20 | Basic |

| 100-200 | ≥80% removal | |||

| Dissolved Copper | µg/L | 5-20 | ≥30% removal | Enhanced |

| Dissolved Zinc | µg/L | 20-300 | ≥60% removal | Enhanced |

Achieving TAPE standards for basic and enhanced treatment requires effective removal of particulates and dissolved copper and zinc. As discussed in Section 2, achieving copper and zinc removal across variable influent quality and pollutant speciation can be best achieved by providing multiple treatment mechanisms, including both inert and sorptive filtration, and including multiple sorptive mechanisms. Some individual materials can provide multiple treatment mechanisms; however, blended or layered filtration media typically allow a for a greater diversity of treatment mechanisms. To consistently remove dissolved copper and zinc, and because cost is not considered a primary selection criterion, filtration media should have a

relatively high sorptive media content. Media should also ideally contain components with internal porosity which contain substantial SA for sorption.

To achieve consistently good pollutant removal, a certain thickness of filtration media and contact time are required. Most stormwater pollutant removal mechanisms that media provide are rapid (on the order of minutes), and many vendor stormwater products achieve very good pollutant removal with very short contact times (Department of Ecology, 2020; Department of Ecology, 2019; Department of Ecology, 2021). A contact time of at least 10 minutes is likely sufficient to attain consistently good pollutant removal. Media thickness is related to contact time, but since stormwater filters remove some fraction of pollutants via depth filtration, media thickness should be considered an independent criterion. Laboratory research suggests that increasing media depth improves performance there is a diminishing return with increased depth (Hatt et al., 2007). Depths range from about 7 inches to about 30 inches for most commercial stormwater treatment technologies. A media thickness between 18 inches and 24 inches is likely adequate for consistently good copper and zinc removal.

Additional details for effective copper and zinc treatment are presented in Section 2.

Co-Benefits for Other Pollutants of Concern

While copper and zinc are identified in this project as the controlling pollutants for media selection, there are additional pollutants of concern in the highway environment including other heavy metals, toxic organic compounds (e.g., polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), 6PPD-quinone), hydrocarbons, and nutrients. A combination of pollutants can contribute to whole effluent toxicity. To the extent possible, media blends should be selected that provide co-benefits for these pollutants and/or provide reduction in stormwater toxicity. Blends containing a larger fraction of reactive materials that provide sorption are expected to provide substantial co-benefits.

Hydraulic Properties

Hydraulic properties of filtration media are a critical consideration. High flow rate filters can treat a much larger volume of runoff in a small footprint; however, time to clogging should be considered when designing and sizing filters. Filtration results in accumulation of fines on the surface (i.e., cake filtration) and deeper in the media (i.e, depth filtration), so media filters always clog after some period of time depending on the particulate loading. Clogging reduces the amount of runoff that can be filtered, thus increasing the amount of runoff that bypass filtration untreated. Clogging can occur at the surface (i.e., cake filtration) and throughout the entire media thickness (i.e., depth filtration).

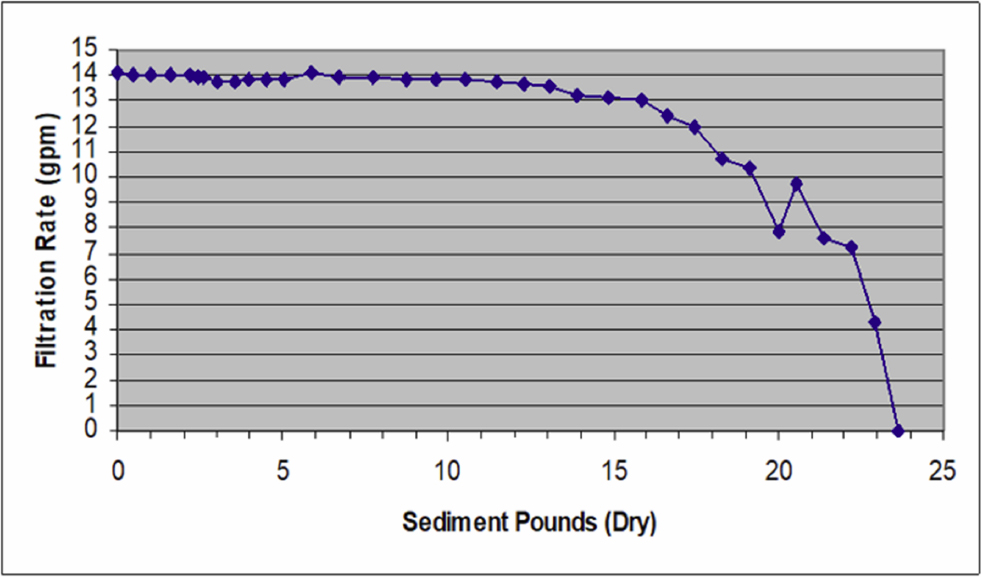

Stormwater filtration media typically clogs after a certain amount of particulate has been filtered by a given media filter. Figure 10 provides an example of this for stormwater testing completed by Contech Engineered Solutions. Data in Figure 10 are for a filter with a radial flow configuration and 7.5 square feet of media SA. The amount of sediment that a particular filter can treat prior to clogging is typically expressed as a load to clog values in pounds of TSS square feet of SA. A review of relevant research and new analyses conducted under NCHRP Report 922 (National Academies, 2019a) suggests that, for high flow rate media filters, a load to clog value of 1 to 2 pounds per square foot of media SA may be suitable for design purposes. This value is similar to laboratory testing conducted as part of the Santa Susana Field Laboratory project (Pitt and Clark, 2010; see Section 4). Both sources suggest that filtration media with higher initial flow rates tend to maintain a specific flow rate for a longer period of treatment.

In some cases, media can be restored by scraping the media surface or mixing the cake formation into the surface of the media. Pitt and Clark (2010) found that this can be effective for two to three maintenance cycles until full media replacement is needed. However, given the logistical constraints of performing O&M in the bridge deck environment, full replacement may be desirable at the time of each maintenance event even if partial media replacement or scraping may be effective.

To maintain relatively long filter lifetime and high filtration rates, filtration media with initial permeability substantially greater than the design flow rate are considered the best choice to maintain treatment at or above the design treatment flow rate for the longest period between O&M cycles. Media that achieve such high flow rates would likely require a relatively coarse PSD. Gradation of high flow rate media are generally uniform with the specifications focused on the particle size range. For high flow rate media with ranges from 100 to 200 inches per hour media PSDs vary, but commonly media would primarily consist of particles passing ½" screen and retained on Number 8 screen.

The flow rate of runoff through a media filter can either be uncontrolled or throttled using outlet controls. In uncontrolled configurations, runoff passes through the filtration media at whatever flow rate the media will support, typically considered to be the media saturated hydraulic conductivity. This approach can provide effective treatment, however, during lower flow rates water can pass through filtration media rapidly via preferential pathways. In outlet-controlled configurations, a valve, orifice, or weir are using to throttle the flow rate of water through the filter to a rate less than the saturated hydraulic conductivity. This design approach induces saturation of filtration media at flow rates less than the design flow rate which could improve pollutant removal of dissolved copper and zinc by saturating a greater portion of filtration media and thus providing access to a greater volume of media and sorption sites. Outlet controls are typically designed so that, during the early life of the filter the flow rate is primarily controlled by the orifice. As the filter becomes partially clogged with solids, the flow rate becomes more and more dependent on the diminishing permeability of the media, until at the end of the life of the filter, the flow rate is entirely controlled by the permeability of the clogged media. Research by Lenhart indicates that once the control reverts to the media that head loss across the media bed is exponential and the filter bed is near its operational life. (Stormwater Management, Inc., 1999). For media filters in the bridge deck environment

that are likely to be maintained relatively infrequently, outlet controls that provide limited throttling sufficient to achieve desired contact times may be a good design choice.

Physical and Mechanical Strength

The physical and mechanical strength of filtration media are important primarily as they relate to the potential for clogging. Friable media, especially when transported long distances or when blended with harder materials (e.g., sand) can physically break and create finer particles which then can reduce the flow rate of media. Compressible media can also pose challenges for maintaining high flow rates, since physical compression of such media can lead to smaller pore spaces between media particles, and thus lower media permeability. Generally, relatively hard, incompressible, and environmentally stable media are recommended for filtration media. Additionally, to limit the creation of fines during processing, filtration media should be screened, blended, and deployed using less physically aggressive methods. Media blending, for example, should use drum mixers versus bucket loaders to avoid abrasion and achieve higher degrees of media uniformity. Media also should not be compacted when placed into the filter box.

Commercially Availability from Multiple Suppliers

State DOTs and municipalities that would install bridge deck filtration devices do not typically permit the use of sole-source contracting or material purchases unless there are cost-effectiveness justifications to do so. There are certain alternatives whereby detailed performance specifications can result in a similar outcome. The research team focused on media blends that are commercially available from multiple suppliers to avoid sole-source contracting rules. Additionally, due to concerns about intellectual property law, the research team did not attempt to determine or estimate the components of proprietary media blends. Instead, the media blend should include materials that can be produced and blended by multiple high-quality mixed media suppliers.

Media Replacement and Disposal

Stormwater filters installed in the bridge deck environment are likely to experience high hydraulic and pollutant mass loading, requiring relatively frequent maintenance. To be feasible, maintenance and material disposal/use must be relatively simple. Additionally, given the cost of performing maintenance in the bridge deck environment, O&M cycles should be as long as possible, and at a minimum 1 year. The length of O&M cycles will likely be a function of media clogging characteristics and the rate of solids loading to filtration media. This will be explored in greater detail in Phase 1b and 2.

Media replacement for nearly any filtration media can be completed in a number of typical ways including manual removal (i.e., shovels), cartridge removal, or with a vacuum truck. The applicability of these methods will largely depend on the physical design of the filter and its location on a bridge, so this will be explored further in Phase 2. Media that is removed from filters is typically disposed in the same manner as street sweepings or catch basin cleanings (Lenhart, 1998), so is typically landfilled as non-hazardous waste since pollutant concentrations in spent stormwater media rarely, if ever, exceed hazardous waste thresholds.

Summary

This section outlines multiple practical and technical factors that must be considered in selecting treatment media, including factors related to performance, longevity, procurement, construction, and O&M. These factors were used to evaluate the various blended media options discussed in Section 4.

4. Review of Tested Filtration Media Blends

Literature Review and Assessment Approach

The research team reviewed data and literature from projects that tested copper and zinc removal from real stormwater using stormwater filtration blends. We reviewed pollutant removal performance, as well as additional information regarding media flowrates, material properties, and clogging frequency. Results from this review along with other practical considerations. form the primary basis for the proposed media blend in Section 5.

Limiting this assessment to media blends, rather than individual components is intended to simplify the media selection process by avoiding lengthy assessments of novel filtration components and blends. Further, restricting this assessment to only those projects that used real stormwater is intended to account for the complexity of PSD and metals speciation that exists in the environment. As detailed above, these, and other factors can greatly influence media filter performance, therefore significant uncertainty is introduced when attempting to extrapolate laboratory performance using synthetic stormwater to real-world field performance.

To identify relevant project data, the research team conducted searches of peer-reviewed literature databases, searches using typical search engines, and inquiries with professional networks including members of the Panel.

Databases of peer-reviewed literature (e.g., Compendex, Engineering Village, Web of Science) were searched for publications using key phrases like “stormwater dissolved metals removal”. Those searches returned almost exclusively laboratory column studies conducted in academic settings with a focus on treatment mechanisms. Most used synthetic stormwater. There are several reasons why this type of testing is preferred by academics including:

- One can fully exhaust the adsorption capacity of the media in a timeframe of a week, rather than the years it would take in the field.

- One can evaluate a variety of filtration media blends and components concurrently, allowing a broader search for top-performing materials.

- One can evaluate various configurations, like layering of media with different properties to target a variety of both organic and inorganic constituents.

- One can control the factors affecting adsorption by providing constant and uniform hydraulic loading rate, constant influent concentration, and constant pH.

Typical internet searches using Google and Bing primarily returned proprietary media blends and media components. Given that most of these materials are proprietary and component information are not available they were not considered as viable blends for this project. Furthermore, vendor-supplied data in marketing materials may not be peer-reviewed.

The most productive approach to identifying suitable studies was based on the personal knowledge of the research team and members of the Panel. This approach identified four projects which are discussed in the following subsections. The research team also reviewed documents associated with several TAPE-approved treatment devices.

Western Washington Media Studies

Project Overview and Testing Approach

Herrera Environmental Consultants conducted a series of studies from 2015 to 2020 with the goal of developing recommendations for a new Western Washington bioretention soil media (BSM) that effectively removes phosphorus and dissolved copper and zinc. Additional criteria for the proposed BSM were that it be was affordable, easily available in Western Washington, and able to reduce stormwater toxicity for aquatic organisms. Although this project was intended to assess media for bioretention, the results are relevant for high flow rate media filters because testing was completed at flow rates typical of high flow rate filters. The project included a preliminary phase and a final phase of testing.

Preliminary phases of testing included evaluating different media components and blends for pollutant leaching potential (including copper and zinc), hydraulic conductivity, and pollutant removal form real stormwater (Herrera, 2015). Select media components with low individual copper and zinc leaching were mixed into eight bioretention mixtures. These eight mixes were then tested for hydraulic conductivity and removal efficiency of copper and zinc using real stormwater. Important findings from preliminary testing included:

- The current Washington State standard BSM (60/40 mix of sand and compost), tested in this study as a basis of comparison, exported significant pollutant loads including nitrate/nitrite, phosphorus, total copper, and total zinc.

- Other blends exported significantly less dissolved and total copper, and export attenuated more rapidly than for the standard BSM.

- The best performers for copper were those media mixes containing coconut coir pith and either GAC or biochar (referred to as high carbon wood ash in these studies, though marketed as biochar by the supplier).

These preliminary tests informed media components and blends evaluated in the final phase of testing (Herrera, 2020). The remainder of this review focuses on the final phase of testing.

Eight different media mixes were flushed, then tested for hydraulic conductivity and removal efficiency of copper and zinc. The tested media mixes are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Media mixes and compositions included in the Western Washington Media final study

| Treatment | Primary Component | Secondary Component | Tertiary Component | Surface Compost Mulcha | Polishing Layerb | Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity (in/hr)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment 1d | Ecology sand (60%) | Compost (40%) | -- | No | No | 190 |

| Treatment 2 | Ecology sand (60%) | Compost (40%) | -- | No | Yes | 220 |

| Treatment 3 | Volcanic sand (70%) | Coconut coir pith (20%) | Biochar (10%) | Yes | No | 165 |

| Treatment 4 | Volcanic sand (70%) | Coconut coir pith (20%) | Biochar (10%) | Yes | Yes | 195 |

| Treatment | Primary Component | Secondary Component | Tertiary Component | Surface Compost Mulcha | Polishing Layerb | Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity (in/hr)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment 5 | Volcanic sand (70%) | Coconut coir pith (20%) | Biochar (10%) | No | No | 180 |

| Treatment 6 | State sand (70%) | Coconut coir pith (20%) | Biochar (10%) | No | No | 190 |

| Treatment 7 | Lava sand (70%) | Coconut coir pith (20%) | Biochar (10%) | No | No | 355 |

| Treatment 8e | Lava sand (70%) | Coconut coir pith (20%) | Biochar (10%) | No | No | 360 |

a Surface mulch was a 2-inch layer of compost.

b Polishing layer consisted of a 12-inch layer of 90% state sand, 7% granular activated alumina, and 3% iron aggregate.

c Saturated hydraulic conductivity measured during falling head tests.

d 2012 Washington State recommended media mix, used as a basis of comparison for other mixes.

e The flow rate through Treatment 8 was controlled using an orifice outlet control.

All eight media blends were packed into 8-inch inside diameter (i.d.) polyvinyl chloride (PVC) test columns and then subjected to leaching tests, hydraulic conductivity analysis, and pollutant removal testing using real stormwater. Treatments 1 through 7 were tested without any hydraulic controls, meaning that the flow rate of water through the media occurred as quickly as the media permitted. Treatments 5, 6, and 7 differed only in the sand source. Treatment 8 was the same media blend as Treatment 7 but was tested with an outlet orifice control to reduce the flow rate of water through the test column.

Treatments 2 and 4 included a 12-inch thick polishing layer consisting of 90% state sand, 7% granular activated alumina, and 3% granular elemental iron. Treatments 3 and 4 also included a 2-inch layer of compost mulch at the surface.

Hydraulic Performance

Following the initial flushing period during the leaching tests, the saturated hydraulic conductivity of each media mixture was evaluated using falling head experiments.

Saturated hydraulic conductivities were extremely high, ranging from 165 to 360 inches per hour (see Table 4). The highest hydraulic conductivities were seen by the two treatments (one freely draining, and the other outlet controlled) that contained lava sand, coconut coir pith, and biochar (high carbon wood ash). These extremely high values for hydraulic conductivity may not be reflective of field performance, however, they do suggest that similar media mixtures would exhibit relatively high flow rates that could be applicable for small footprint BMPs. Hydraulic conductivity tests were not repeated during the research, so no inferences can be made about clogging or O&M cycles.

Water Quality Testing and Target Pollutant Effectiveness

Five dosing experiments were conducted using the eight media mixes described above, though Treatments 1 and 8 were only dosed twice. Stormwater used in the dosing experiments was collected from State Route 520 in Seattle, Washington. Influent concentrations of copper and zinc were typical of, though higher than, median pollutant concentrations in highway runoff (see Section 2) except for runoff used for the fourth dosing event which contained exceptionally high concentrations of copper and zinc. Testing was

completed at a treatment flow rate of approximately 14 inches per hour for approximately 3 hours and 20 minutes per event. The treatments a saturated hydraulic conductivity of more than 100 inches per hour, and with the exception of Treatment 8, the systems were not outlet controlled. Therefore, water likely passed through the media via unsaturated flow at a rate faster than the loading rate, such that the residence time of the water in the media was likely much less than what is implied by 14 inches per hour.

All treatments performed very well for the removal of total copper (Figure 11, Table 4). The top-performing media mixes were Treatments 2 and 4 which contained a polishing layer. Treatments 5 – 7, consisting of mixtures of sand, coconut coir, and biochar were also highly effective and performed similarly well. Treatment 8 performed slightly better than Treatment 7, suggesting orifice controls may improve removal performance for metals. Treatments 1 and 3 had the worst performance, potentially due to the presence of compost but no polishing layer. Preliminary phases of this project clearly indicated that compost can export copper.

Data for dissolved copper concentrations showed similar trends, with blends containing compost exhibiting the worst performance. Treatments 2 and 4 which contain the polishing layer were the most effective for removal dissolved copper, achieving median effluent concentrations of 1.9 µg/L and 1.7 µg/L, respectively. Among those treatments not containing compost, the difference between media total copper and media dissolved copper was similar for all treatments, ranging from a difference of 2.1 µg/L to 3.9 µg/L. These data suggest that each of the treatments not containing compost achieved similar removal of particulate copper, so differences in total copper concentrations are related to differences in dissolved copper removal.

All treatments except for Treatment 1 performed exceptionally well for the removal of total zinc (Figure 11, Table 5). Treatment 4 performed slightly better and more reliably than the other treatments. Dissolved zinc data were somewhat different, with Treatments 2 and 4 outperforming other blends, likely due to the presence of the polishing layer. The remaining six treatments performed similarly well, suggesting that compost is not a significant source of dissolved zinc.

Table 5. Water quality treatment performance summary for copper and zinc in the Western Washington Media final study

| Media Mixture | Copper (μg/L) | Zinc (μg/L) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Dissolved | Dissolved % Removal1 | Total | Dissolved | Dissolved % Removal1 | |

| Influent | 83.0 | 28.4 | - | 292 | 131 | - |

| Treatment 1 | 21.0 | 13.8 | 51% | 46.1 | 16.6 | 87% |

| Treatment 2 | 5.4 | 1.9 | 93% | 12.6 | 7.0 | 95% |

| Treatment 3 | 22.5 | 16.8 | 41% | 23.1 | 19.5 | 85% |

| Treatment 4 | 4.0 | 1.7 | 94% | 8.9 | 3.5 | 97% |

| Treatment 5 | 15.6 | 12.2 | 57% | 18.0 | 13.5 | 90% |

| Treatment 6 | 14.2 | 10.3 | 64% | 22.5 | 19.7 | 85% |

| Treatment 7 | 15.7 | 12.6 | 56% | 21.9 | 19.9 | 85% |

| Treatment 8 | 10.4 | 6.9 | 76% | 19.9 | 13.5 | 90% |

1 Dissolved fraction percent removal data are raw values. Because TAPE standards require comparing the 95% confidence interval of dissolved phase percent removal to the TAPE standards, these data dot indicate that tested media meet TAPE standards.

The best and most consistent performance dissolved and total copper and zinc removal was achieved by Treatment 4 whch contained a blended media of 70% volcanic sand, 20% coconut coir pith, and 10% biochar in addition to a polishing layer. Compared to Treatment 3, which was the same blend without the polishing layer, Treatment 4 had 82% lower total copper and 61% lower total zinc concentrations in effluent, suggesting the addition of a polishing layer to a sand / coconut coir / biochar blend significantly improves copper and zinc removal performance. It appears likely that the addition of a polishing layer to Treatments 5, 6, 7, and 8 would have significantly improved copper and zinc removal resulting in blends achieveing extremely low effluent concentrations of total copper and total zinc.

This project was not intended to complete TAPE certification for the tested media blends, however, some statistical analyses were presented to compare data to TAPE standards. These analyses indicated that Treatments 4, 5, 6, and 7 would achieve TAPE standards for enhanced treatment, but that only Treatment 8 (with outlet control) would meet TAPE standards for basic treatment. Relatively poor TSS removal results

could be related to the fact that the sand fraction in each of the media blends was not rinsed and sieved so may have contained sigificant amounts of fine particles which could have leached from filtration media.

These results suggest that, overall, media blends containing a mix of sand, coconut coir, and biochar can achieve very low effluent concentrations for copper and zinc at treatment flow rates of approximatelty 14 inches per hour using real stormwater. Given that the hydraulic conductivity of the media mixtures was much higher than this, it is likely that these mixtures could achieve good removal of copper and zinc at higher flow rates. The addition of a polishing layer can further improve performance, and may result in better long-term performance.

In addition to providing good removal of copper and zinc, Treatment 4 achieved excellent removal of both total phosphorus and ortho-phosphorus. This treatment contains a polishing layer and does not contain compost, suggesting that this combination may provide geood removal of phosphorus.

Boeing Santa Susana Field Laboratory - Media Testing Study

Project Overview and Testing Approach

Extensive laboratory tests were conducted in 2010 to select a media mixture to meet low water quality permit limits for a variety of stormwater pollutants, including copper and zinc, at the Santa Susanna Field Laboratory (SSFL) in southern California (Pitt and Clark, 2010). Media studies were performed in a university laboratory. The selected media was used in the full-scale design of a large stormwater biofilter at the SSFL site, which has now been monitored for 10 years.

Ten media mixes were developed that contained six different materials: rhyolite sand, coconut shell GAC, surface modified zeolite, another zeolite currently used on the site as part of other stormwater treatment systems (site Zeolite), a filter sand also being currently used on the site (site sand), and sphagnum peat moss. The media mixes were selected to test individual component performance and the performance of several combinations of components. The media mixes are shown in Table 6.

Table 6. Media mixes and compositions included in pilot testing studies for the Boeing Santa Susana Field Lab Testing

| Mix Name | Mix (by volume) |

|---|---|

| GAC | 50% GAC, 50% filter sand |

| Peat Moss (PM) | 50% peat moss, 50% filter sand |

| Rhyolite Sand (R) | 50% rhyolite sand, 50% filter sand |

| Site Sand (S) | 100% site sand |

| Site Zeolite (Z) | 50% site zeolite, 50% filter sand |

| Surface modified zeolite (SMZ) | 50% surface modified zeolite, 50% filter sand |

| Rhyolite sand and surface modified zeolite (R-SMZ) | 50% rhyolite sand, 50% surface modified zeolite |

| Rhyolite sand, surface modified zeolite, and granular activated carbon (R-SMZ-GAC) | 1/3 rhyolite sand, 1/3 surface modified zeolite, 1/3 GAC |

| Mix Name | Mix (by volume) |

|---|---|

| Rhyolite sand, surface modified zeolite, granular activated carbon, and peat moss (R-SMZ-GAC-PM) | 30% rhyolite sand, 30% surface modified zeolite, 30% GAC, and 10% peat moss |

| Site sand, site Zeolite, and Granular Activated Carbon (layered mixture) (Layered S-SMZ-GAC) | 1-foot-thick layers of site sand, site zeolite, and GAC |

Media evaluation activities included:

- Downflow column tests with periodic testing “events” using real stormwater to evaluate clogging, pollutant removal efficiency, and pollutant removal breakthrough.

- Media pollutant removal capacity and kinetics testing to determine the potential pollutant load capacity of each media blend.

Column tests were performed using 3.5-inch i.d. glass columns with 38 inches of engineered media. The test columns had no outlet controls, so water flowed through the media under “media-controlled” hydraulics.

Hydraulic Performance

Flow rate testing was completed following each water quality testing event throughout column testing. Results indicated that the 10 media mixes achieved average initial flow rates (i.e., before significant clogging occurred) between approximately 5 inches per hour and 33 inches per hour as presented in Figure 12 and Table 7. The following media mixtures achieved the highest flow rates and would likely be applicable for small footprint treatment systems in the bridge deck environment:

- GAC

- R-SMZ-GAC

- Site zeolite (Z)

- Rhyolite sand and surface modified zeolite (R-SMZ)

- Rhyolite sand, surface modified zeolite, granular activated carbon, and peat moss (R-SMZ-GAC-PM)

Separate clogging tests were performed to determine the amount of loading and time that could be achieved by each media mix before clogging was experienced. Separate clogging tests were performed to estimate TSS load to initial maintenance and estimated load to clog for large-scale applications. Load to initial maintenance was calculated as the amount of TSS load before flow rates dropped below approximately 8 inches per hour. Load to clog values were calculated by multiplying load to initial maintenance values by a factor of five based on the experience of the research team. These data are presented in Figure 12 and Table 7. Initial flow rates correlated relatively well with estimated load to clog values, suggesting that coarser media with relatively high initial flow rates are able to operate for a longer period of time prior to clogging.

Maintenance testing was also completed during column testing to assess the effectiveness of different types of maintenance for restoring media flow rates. During the water quality column testing maintenance was performed on each column when flow rates dropped below a pre-determined threshold of 8 inches per hour. Maintenance consisted of either surface scraping without media removal (i.e., raking media to dislodge surface crusting) or scraping and removal of the top several inches of media. Surface scraping without removal did little to restore flow rates. Removal of the top several inches of media resulted in improved hydraulic performance for a short duration, except for the site sand, which responded very well to media removal. The improvement in hydraulic performance diminished after each maintenance round

suggesting some amount of clogging deeper in the media. Maintenance could be performed generally two to three times before the media flow rate did not respond to maintenance. It was hypothesized that particle trapping occurred over a range of filter depths and was not concentrated on the surface, except in the case of the sand filter. This allowed longer operation times between maintenance but limited the benefits of surface maintenance.

Because O&M activities appeared to have diminishing returns, these data suggest that, at least in the bridge deck environment where mobilization costs for O&M are often very high, full media replacement may be the preferred O&M activity rather than surface scraping or mixing, even if this increases the material cost associated with media procurement. Load to initial maintenance data suggest that a value between 1 and 2 pounds of sediment per square foot of media bed (5 to 10 kilograms per square meter) may be a suitable design value for media blends of similar types, with the possibility that more granular and permeable media beds may withstand greater loading before clogging occurs.

Table 7. Estimated load to initial O&M and time to media replacement (clogging) for media mixes included in the Boeing Santa Susana Field Lab Testing

| Media Mix | Observed load to Initial O&M (lb/ft2)1 | Estimated Load to Clogging (lb/ft2)2 | Initial Flow Rate (in/hr) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAC | 1.55 | 7.77 | 32.8 |

| Peat Moss (PM) | 0.82 | 4.09 | 19.7 |

| Rhyolite Sand (R) | 1.43 | 7.15 | 24.6 |

| Site Sand (S) | 0.41 | 2.05 | 4.9 |

| Site Zeolite (Z) | 0.70 | 3.48 | 29.5 |

| Surface modified zeolite (SMZ) | 1.14 | 5.72 | 21.3 |

| Rhyolite sand and surface modified zeolite (R-SMZ) | 1.55 | 7.77 | 29.5 |

| R-SMZ-GAC | 2.16 | 10.8 | 32.8 |

| Rhyolite sand, surface modified zeolite, granular activated carbon, and peat moss (R-SMZ-GAC-PM) | 2.25 | 11.2 | 29.5 |

| Layered site sand, Site Zeolite, and Granular Activated Carbon (layered S-Z-GAC) | 1.35 | 6.75 | 23.0 |

1 Observed load to initial O&M represent the TSS mass load applied before the media flow rate dropped below approximately 8 inches per hour, except for the site sand column which had an initial flow rate of 4.9 inches per hour.

2 Estimated load to clog values were calculated by multiplying observed load to initial O&M values by five to estimate load to clog of full-scale systems. A factor of five was chosen by the project team based on prior experience converting column study data to larger tests.

Water Quality Testing and Target Pollutant Effectiveness

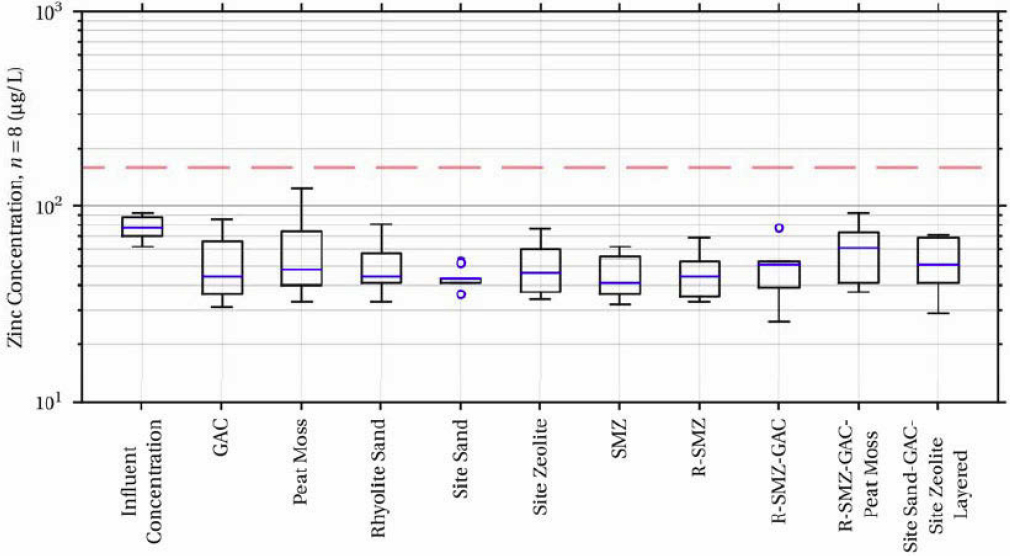

Stormwater quality testing was completed using real stormwater that was modified to increase pollutant concentrations to applicable ranges for the site. Metals were adjusted to about 100 μg/L to ensure measurable influent concentrations and evaluate media performance during high influent concentration periods. Major cations and anions were adjusted to reasonable values for urban runoff. Suspended solids concentrations were adjusted using local, sieved soil. Table 8 presents the average influent concentration and average effluent concentration for total copper and zinc during the testing period. The same data are presented in Figure 13 and Figure 14 using boxplots.

Table 8. Total copper influent and media effluent concentrations and removal efficiencies for separate media and mixes included in the Boeing Santa Susana Field Lab Testing

| Media Mix | Mean Total Copper (μg/L) | Mean Total Zinc (μg/L) |

|---|---|---|

| Influent | 125 | 77 |

| GAC | 4 | 48 |

| Media Mix | Mean Total Copper (μg/L) | Mean Total Zinc (μg/L) |

|---|---|---|

| Peat Moss (PM) | 13 | 57 |

| Rhyolite Sand (R) | 42 | 49 |

| Site Sand (S) | 31 | 43 |

| Site Zeolite (Z) | 41 | 47 |

| Surface modified zeolite (SMZ) | 39 | 44 |

| Rhyolite sand and surface modified zeolite (R-SMZ) | 48 | 44 |

| Rhyolite sand, surface modified zeolite, and GAC (R-SMZ-GAC) | 7 | 48 |

| Rhyolite sand, surface modified zeolite, GAC, and peat moss (R-SMZ-GAC-PM) | 20 | 59 |

| Site sand, Site Zeolite, and GAC (layered S-Z-GAC) | 8 | 52 |

Influent total copper concentrations in this study were between 100 and 150 μg/L which would be between the 90th and 99th percentile of data in the Transportation BMP Database (see Section 2). All media

and media mixes showed substantial copper reductions. Mixtures containing GAC achieved the largest copper reductions with mean effluent copper concentrations less than 10 µg/L.

The mean influent total zinc concentrations in this testing was 77 µg/L which be between the 25th and 50th percentile of total zinc influent concentrations in the Transportation BMP Database (see Section 2). All media and mixes showed moderate total zinc removal with mean effluent zinc concentrations between 43 µg/L and 59 µg/L. The highest zinc reductions were seen in media composed of site sand and media composed of rhyolite sand, surface modified zeolite, and GAC.

Pollutant breakthrough was also assessed with long-term full-depth column tests. The goal of these tests was to repeatedly subject test columns to polluted stormwater until pollutant removal effectiveness notably declined. However, no media mix achieved breakthrough for total copper (i.e. copper was removed effectively throughout the duration of the test), suggesting long-lived chemical removal capacity. Pollutant breakthrough testing was completed for hydrologic durations greater than expected clogging times based on clogging test results, so these data suggest that clogging is likely to occur before any pollutant removal media exhaustion, at least for total copper.

Several media leached pollutants during the column testing for zinc (i.e. the first sample from the column showed zinc export, but the remaining samples in the test period did not). These media and mixes included those listed below. These media mixes may require rinsing prior to placement for treatment.

- GAC

- Peat Moss

- Rhyolite Sand

- Rhyolite Sand, surface modified zeolite, and GAC

In 2011, media consisting of 1/3 Rhyolite sand, 1/3 activated carbon, and 1/3 surface modified zeolite was installed in a number of large-scale treatment systems at SSFL including bioswales and a biofilter. Data from nearly 10 years of operation show that the metals removal performance of the media has not declined since its installation (Pitt and Colyar, 2020). In 2018 – 2019, the maximum effluent concentration of copper was about 6.5 μg/L (maximum influent concentration of 10.5 μg/L) across several stormwater controls. Reductions of copper were statistically significant. Data for zinc were not readily available since there is no regulatory target at the site.

Granular Ferric Oxide Field Tests

Project Overview and Testing Approach

Full-scale testing of ferric oxide engineered media was recommended as an outcome of NCHRP Report 767: Measuring and Removing Dissolved Metals from Storm Water in Highly Urbanized Areas (National Academies, 2014a). Subsequent field testing was completed and documented in NCHRP Web-Only Document 265: Field Test of BMPs Using Granulated Ferric Oxide Media to Remove Dissolved Metals in Roadway Stormwater Runoff (National Academies., 2019b). This study evaluated full-scale vault and bioretention swale-type filtration BMPs with ferric oxide-amended filtration media.

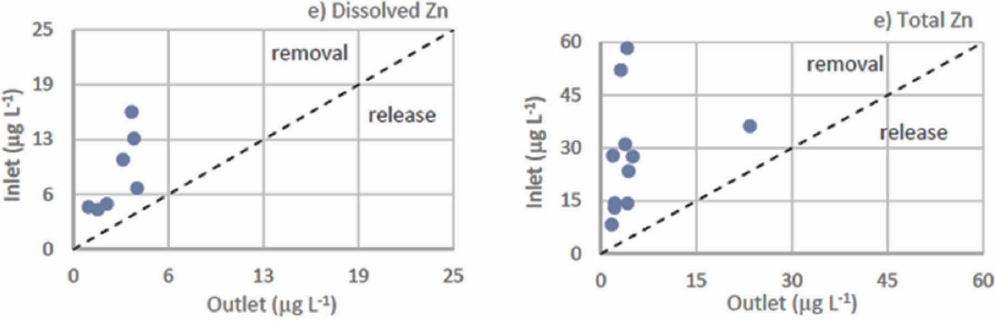

This review focuses on the ferric oxide filter installed in a bioretention swale at Woodlynn Avenue in Maplewood, Minnesota. This had media filtration rates in the range of 4 to 12 inches per hour, which is lower than would be desirable for a bridge deck environment, but somewhat transferable. In contrast, the vault filter had treatment flow rates of approximately 0.5 inches per hour and less, so these data were not considered relevant for small footprint filters that would be installed in the bridge deck environment.