Developing a Guide for On-Bridge Stormwater Treatment Practices (2024)

Chapter: 3 Findings and Applications

CHAPTER 3

Findings and Applications

Chapter Organization

This chapter summarizes the discrete findings of the research phases. Findings are organized by the same phases discussed in Chapter 2 (Research Approach). This research project involved progressive phases where interim findings and decisions informed the next stages of research. This Chapter primarily documents the interim findings and recommendations. Chapter 4 provides a high-level assessment of the overall findings of the research project. Additionally, the primary findings of the research project are contained in the Guide. As discussed earlier, this report intentionally does not repeat the same findings that are contained in the Guide. Instead, we provide references to specific sections of the Guide.

Task 1a Findings: Stormwater Treatment Processes and Options

This section provides an overview of Task 1a findings. Additional detail is provided in Appendix A.

Stormwater Characterization

Per the research statement, this characterization focused primarily on copper and zinc. We did not conduct a characterization of nutrients in highway runoff in Task 1a and this was not the primary driver for selection of treatment processes. However, candidate media blends were evaluated for removal of nutrients.

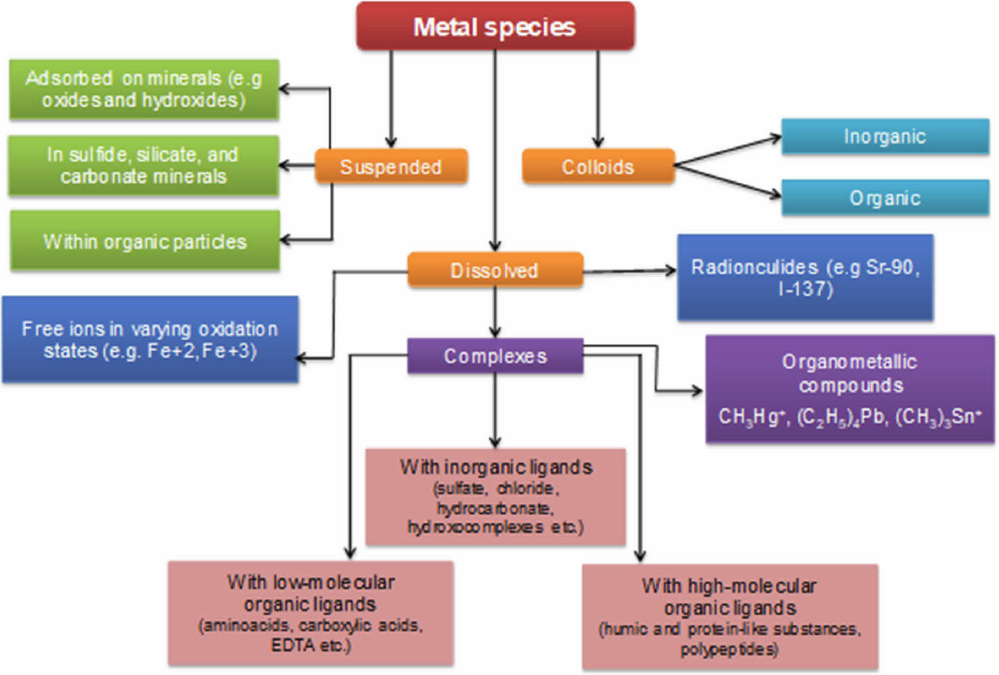

Metal concentrations are commonly separated into total and dissolved phases. One can further discriminate between particulate (total – dissolved) and dissolved. One can also separate dissolved into free ionic forms and colloidally bound (and less biologically available) forms as well.

The particulate phase as it is defined consists of those boxes in green in Figure 1. Although colloidal metal species are, in fact, particulate, their diameter is less than the pore size (about 0.45 μm) of the filters used by analytical laboratories to distinguish between the particulate and dissolved phases. Consequently, the value reported for dissolved metal concentration includes some fraction of colloidal material. Sorption of trace elements to colloidal matter, including nanoparticles, can have a significant impact on metal ion mobility and removal as well as toxicity. Among metals in the true dissolved phase are both free ions as well as metals adsorbed to organic and inorganic ligands. Nason et al. (2012) found that free ionic copper made up less than 1 percent of dissolved copper in the highway runoff from Oregon DOT sites.

Given the numerous factors that can affect speciation and the natural variability of stormwater, stormwater characterization for metals is relatively complex and highly variable. On average, particulate-bound metals account for around two-thirds of metal mass in stormwater runoff. However, there is relatively high variability in the ratio of particulate to dissolved fractions. Within the dissolved fraction, there are several different chemical species, each with different bioavailability and removal mechanisms. The

speciation can vary from site to site and from storm to storm. In order to consistently meet TAPE enhanced treatment benchmarks, a BMP needs to address both total and dissolved metals, including potentially multiple sub-species of dissolved metals.

Candidate Treatment Processes

Media filtration is believed to be the most compatible treatment technology for the target pollutants, treatment goals, and space and weight constraints on bridges. Conventional settling requires too much space and weight of stored water. Hydrodynamic separation could fit but does not achieve necessary levels of metals removal and in particular dissolved removals. In contrast, media filtration is a proven technology for both particulate-bound and dissolved species within relatively small footprints and comparable weight and has been shown to be effective at relatively high flow rates.

Removal of dissolved including colloidal metals requires some form of sorptive process, which can include ion exchange and/or adsorption. The relative role of each sorptive component can vary depending on influent characteristics, and different media materials provide different processes. A combination of media components providing different sorptive mechanisms appears to be desirable, as this provides a robust treatment system across variable influent characteristics.

Clogging is a critical risk for filtration systems. To balance particulate removal with media bed lifespan, a media filtration design that promotes depth filtration and straining more likely to have longer lifecycle

than a design that promotes cake filtration. Additionally, the use of pre-treatment and/or permeable friction course material could reduce influent sediment loads.

Target Media Characteristics

Filtration media for removal of copper and zinc needs to be effective for removing these pollutants, but it should also meet other criteria to be effective. The following primary criteria should be met:

- Media should provide effective removal of copper and zinc across variable stormwater influent quality and pollutant forms at flowrates needed to support feasible bridge deck designs. Specifically, blended media should meet TAPE standards (Washington State Department of Ecology, 2018) for enhanced treatment. This includes 60 percent removal of dissolved zinc and 30 percent removal of dissolved copper for defined ranges of influent concentration.

- Media should provide co-benefits for other common highway pollutants, such as toxic organic compounds, nutrients, and whole effluent toxicity. For nutrients, it is desirable for media to meet Chesapeake Bay Stormwater Performance Standards (Chesapeake Stormwater Network, 2015). This includes around 40 percent removal of total nitrogen and around 60 percent removal of total phosphorus.

- Media should have adequate hydraulic properties to achieve high treatment flow rates and resist clogging.

- Materials should have adequate physical and mechanical strength to resist physical degradation.

- The material specifications should allow DOTs to specify materials that can be provided by multiple suppliers.

- Media blends should be relatively simple to replace with a quality-controlled product that is assured to meet the specifications for treatment and hydraulics.

- Media should allow disposal as a non-regulated waste, if possible.

- Media may be blended or layered; however, for simplicity of maintenance a uniformly blended media is tentatively preferred.

- Media should not be substantially impacted by winter maintenance chemicals, such as deicing salts.

Cost and regional availability are notably not included as primary criteria. Retrofitting a bridge for stormwater treatment, include engineering design and construction of BMPs is likely to be extremely expensive due to the complexities of design and construction. O&M activities are also likely to be expensive as O&M activities on bridge decks likely require lane closures, specialized equipment, and specialized materials, adding cost and logistical concerns. Among these costs and logistical considerations, the cost of a small volume of stormwater filtration media is likely to be minor. In our experience, the difference between a low-cost mix and a specialty mix would likely be less than $500 to $1,000 per BMP unit. Therefore, cost was not considered a primary criterion the filtration media literature review nor in our recommendations.

Similarly, regional material availability was not considered a primary criterion. Given that stormwater treatment has been conducted on only a few bridges, and the fact that such treatment is not expected to be broadly required or feasible, it is unlikely that material volume requirements will be significant. Regionally available media are preferred but shipping relatively small quantities of filtration media long distances from a reputable supplier if needed may be a preferred option from a quality control perspective.

Performance Studies of Candidate Blends

A variety filtration/adsorption blends have been evaluated over the years in various studies as well as part of the Washington State TAPE protocol. Many of these blends are proprietary (e.g., Filterra, MWS Linear, etc.) but others, such as an alternative media tested recently in Western Washington, are in the public domain. We considered the following filtration media blends and associated field studies.

- Western Washington Media Studies: Studies evaluated several potential blends to treated dissolved metals while treating and limiting export of nutrients. The final recommended blends include sand, coconut coir pith, biochar, and a polishing layer including activated alumina. Various blends performed well. The recommended blend is currently being monitored in a full-scale application for TAPE approval.

- Boeing Santa Susana Media Study: This study evaluated several potential blends including granular activated carbon, peat moss, rhyolite sand, local sand, and zeolite. It assessed treatment performance, total sorptive capacity, and the effect of sediment loading on permeability. The recommended blends included of 1/3 Rhyolite sand, 1/3 activated carbon, and 1/3 surface modified zeolite. This was installed at full-scale in 2011 and has been monitored for 10 years with a demonstrated sustained pollutant removal performance.

- Granular Ferric Oxide Field Tests. This material was tested in two field sites (NCHRP Web Only Document 265). Influent concentrations were relatively low to be able to assess performance. The performance did not meet TAPE standards for dissolved metals. Additionally, from previous research, this media is known to be relatively sensitive to the pH of stormwater, which can vary in highway runoff. This can result in inconsistent performance between sites and regions. This mix is targeted primarily at dissolved metals.

- Washington DOT Media Filter Drain (MFD). This BMP type was monitored as part of the TAPE certification process. MFD includes pre-settling, volume reduction via infiltration and evapotranspiration, and engineered media filtration. The engineered media consists of crushed rock, dolomite, gypsum, and perlite. The media is intended to promote coagulation and precipitation of metals. The overall system is typically sized at more than 10 percent of the tributary drainage area, making it much too large for a bridge. Only the filtration media component of the MFD would be compatible with the bridge environment. The available performance data suggests that the media filtration component would not meet TAPE criteria for dissolved copper and zinc.

- TAPE approved manufactured systems. Several proprietary treatment technologies have been approved to meet “enhanced” and “phosphorus” treatment criteria at the General Use Level Designation (GULD) under TAPE at rates of between 96 and 175 inches per hour. Current media filtration products with GULD for enhanced treatment include: (1) Filterra System (with box, or as loose media), (2) Modular Wetland Systems MWS Linear (3) BioPod Biofilter (with box or as loose media), and (4) StormTree Biofiltration Practice. These systems have field-scale, third-party testing to meet TAPE enhanced goals. Media composition is typically proprietary. No efforts have been made under this review to identify components of any proprietary media blends. The blends from these manufacturers of the listed treatment systems above area available in bulk.

- Sand Filters from BMP Database. The International Stormwater BMP Database contains many media filter studies, including sand filters and various types of filters with other media blends. This dataset is mostly sand filters that operate under loading rates lower than what would be feasible in the bridge deck environment. However, this shows that sand filters (often even without amendments) are capable of achieving relatively high removal of TSS, total copper, total zinc,

dissolved zinc, and total phosphorus. Sand filters have limited effectiveness for total nitrogen and dissolved copper.

Each of the studies considered in this section utilized actual stormwater with full-scale or more realistic lab scale assessments. Each of the studies showed relatively strong treatment performance however there is considerable variability in the transferability of these findings to full-scale applications in the bridge deck environment. Table 1 (excerpted from the Task 1a memorandum) provides a summary of the study team’s opinions on the transferability and limitations of these studies.

Table 1. Summary of Practical Implications from BMP Performance Studies

| Study | Transferrable Findings | Limitations or Uncertainties |

|---|---|---|

| Western Washington Media Studies |

|

|

| Boeing Santa Susana Media Study |

|

|

| Study | Transferrable Findings | Limitations or Uncertainties |

|---|---|---|

| Granular Ferric Oxide Field Tests |

|

|

| WSDOT Media Filter Drain |

|

|

| TAPE-Approved Manufactured Systems |

|

|

| Study | Transferrable Findings | Limitations or Uncertainties |

|---|---|---|

| Sand Filters from BMP Database |

|

|

Interim Recommendations for Further Evaluation

Based on the research and evaluation conducted in Task 1a, the research team recommended a non-proprietary media blend based primarily on one of the media blends from the Western Washington Media Studies. The intent of this research was to support designs can be implemented without the use of proprietary materials but would still allow the use proprietary media if a DOT chooses. See Task 2 findings below.

Task 1b Findings: Overall Stormwater Treatment Design

This section provides an overview of Task 1b findings. Additional detail is provided in Appendix B.

Bridge Environment

Through the research performed in Task 1b, we found that bridges have many general commonalities:

- Most parts of a bridge serve a structural purpose and are an integral part of the original structural design. There are relatively limited parts of a bridge that can be modified without potentially impacting structural performance, depending on how “over-designed” they are.

- Space is nearly always constrained in the bridge environment. The types, shapes, and sizes of space available for stormwater treatment differ greatly between bridges based on their unique designs.

- Drainage elements are often much smaller and more tightly spaced that normal highway drainage outfalls.

- Bridges face various vertical constraints related to flood elevation and other clearance requirements.

- O&M of existing bridge drainage infrastructure is currently a relatively high burden for DOTs and requires disproportionate effort relative to other parts of highway O&M due to the need to work in a constrained environment.

- DOTs are experienced in performing stormwater drainage system O&M in the bridge environment. However, existing maintenance regimes are far less intensive than would be needed to inspect and maintain on-bridge BMPs.

Beyond these commonalities, there are a wide range of conditions encountered. When considering bridge retrofit, one needs to be aware that the DOT will be looking at bridges up to 75 years old. The design of bridges has evolved substantially over the years, many other considerations influence site-specific designs (e.g., abutment types, earthquake standards, architectural choices, etc.), so there may be few common structural or drainage features amongst bridges. Our overall finding is that each bridge is often quite unique, and there are a very large number of combinations of conditions encountered in the bridge environment that may influence the feasibility, placement, design, and O&M of stormwater treatment elements.

Design Requirements

There are many challenges to implementing on-bridge stormwater treatment which leads to the conclusion that, wherever possible, and when required, stormwater should be routed to the abutments or adjacent areas where BMPs can be installed and maintained off the bridge. This is consistent with the

finding of NCHRP Report 778. However, consistent with the research statement for the current project, our research is focused on addressing circumstances where on-bridge stormwater treatment is required as a retrofit, and treatment cannot be implemented on adjacent land or otherwise replaced or compensated for with off-site alternatives.

As part of this project, we went through an effort of prioritizing design constraints into three tiers:

-

Tier 1: Baseline Assumptions. This tier includes relatively rigid constraints that serve as starting assumptions for the design process. These are overriding criteria that render on-bridge stormwater treatment infeasible if they cannot be satisfied. These include.

- Designs should not rely on significant modification to the bridge deck or other structural elements that would compromise their functions. Designs should avoid reducing the hydraulic capacity of the existing drainage system.

- The location and design of BMPs must allow for safe and feasible operation and maintenance access with available equipment.

These fundamental constraints had the following implications for design development:

- New or substantially enlarged penetrations through the bridge deck are unlikely to be feasible due to structural issues and potential pathways for corrosion.

- With the exception of permeable friction course (which is not the subject of this research), BMPs must be installed below the bridge deck or on the side of the bridge, also below the surface elevation of the bridge deck to ensure that the BMP does not reduce hydraulic capacity.

- Because the number of discharge points is typically large, it may be infeasible or pose a prohibitive O&M burden to install BMPs at each drain outlet, especially in cases where drainage systems do not already collect runoff from multiple inlets. Consequently, BMPs will commonly require a conveyance system below or adjacent to the bridge deck to convey the water to a more central location for treatment.

- The location of the BMP needs to be determined based on evaluation of structural risks, routing of flows, access for inspection and maintenance, and constructability. This can significantly limit options.

-

Tier 2: Primary Design Factors. This tier includes key macro-level design factors that dictate the overall design approach that may be feasible. These include:

- BMP sizing and weight: How large of system needs to be installed? This influences the size and weight of the system, which in turn influences the opportunities for placement. The Task 1b memorandum contains initial sizing estimates. The size of the BMP will be driven by how much area it treats, local precipitation patterns and treatment goals (i.e., flowrate to be treated), the target maintenance interval between clogging events, and the sediment loading rate (including the potential effect of traction sand from cold weather maintenance).

- Floodway and other clearance impacts: Can the BMPs extend below the lower edge of the bridge girders? What analysis is needed to determine this?

- Conveyance: What options are feasible to convey water to a centralized BMP without reducing drainage capacity? This influences what locations are feasible and how

- Relative structural risks: What locations could reasonably support the weight and configuration of the BMP and have the greatest chance of being deemed acceptable via structural review? The Task 1b memorandum contains a relative assessment of structural risks and potential viability for BMPs mounted to (1) Substructure – Bents or Piers, (2) Superstructure – Beams, and (3) Edge Barrier – Railing or Parapet.

- Accessibility for construction and O&M: What locations can be safely accessed for construction and O&M with typical bridge construction and maintenance equipment? This should further incorporate the unique maintenance requirements for BMPs compared to other current aspects of bridge inspections and maintenance. For example, the equipment needed to maintain BMPs may be different than that used for periodic under bridge inspection. The Task 1b memorandum contains an assessment of inspection/maintenance access, personnel safety, equipment requirements, and cold climate O&M considerations that pertain to each of the potential mounting locations identified above.

- Tier 1+2: Assessment of Potential BMP Locations. This section of the Task 1b memorandum (Appendix B to this report) integrated the Tier 1 and 2 design factors to assess potential BMP locations within the bridge environment in cases where it is not feasible to route water to land. Table 2 (excerpted from the Task 1b memorandum) summarizes the most important pros and cons of each location and potential factors that could render the option infeasible for a given bridge. This table was subsequently refined and included in the Guide.

complex the added conveyance system would need to be. The Task 1b memorandum contains a review of different bridge drainage paradigms and conceptual examples of a how collection and conveyance system could route water to a BMP from multiple drainage areas.

Table 2. Comparison of pros/cons for BMP implementation by installation location.

| Location | Pros | Cons | Potential Fatal Flaws |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bents or Piers |

|

|

|

| Beams or Girders |

|

|

|

| Location | Pros | Cons | Potential Fatal Flaws |

|---|---|---|---|

| Edge Barriers |

|

|

|

-

Tier 3: Supporting Design Factors. This tier includes detailed aspects of the design that can be developed after the overall design feasibility is established. In some cases, these may have the effect of rendering a design infeasible. However, more often these are design details that must be worked through to produce a constructable and maintainable design. The Task 1b memorandum identifies the following design factors for more detailed assessment in support of developing a complete BMP design:

- BMP Geometry and Flow Configuration

- Treatment Media

- Pretreatment Options

- BMP and Conveyance Construction Materials

- O&M Procedures

- Cold Climate O&M Issues and Needs

These factors were integrated into the prototype BMP options developed in Task 2.

Design Case Studies and Alternatives Evaluation

We conducted interviews with DOTs to inform the research and gain practical insight. As a follow-up to these interviews, we obtained three case studies of bridges to assess potentially viable designs that would allow stormwater to be treated on the bridge. These are initial case studies and are not the same as those included in the Guide. These initial case studies are included in Appendix B.

Interim Findings and Recommendations from Task 1b

Bridges are unique structures. While there are some commonalities in bridges, the differences that exist are very important for the design, construction, operation, and maintenance of a stormwater treatment system. In the sections above, we identified and briefly summarized our evaluated key design considerations and approaches for how to determine feasibility and an overall BMP design. This reinforces the need for project-specific engineering and alternatives analysis to meet the various objectives.

The Task 1b memo (Appendix B to this Report) identified baseline assumptions and primary factors that need to be carefully evaluated to determine where BMPs can be located and configured and how the overall conveyance and treatment system can be designed, constructed, and maintained. The most important factors to Guide the overall design and feasibility assessment include:

- structural capacity,

- ability to capture and convey flow,

- ability to avoid floodway or other clearance impacts,

- ability to construct the BMP,

- required maintenance intervals, considering both normal and cold climate operations, and

- ability to provide safe and affordable O&M access, and other considerations.

Designers will benefit from guidelines about how to integrate these factors and examples of design approaches and associated cost estimates. However, we believe there is very little opportunity to have standard off-the-shelf stormwater conveyance and treatment designs that cover the wide range of locations, bridge structural elements, conveyance requirements, connection details, and other factors that pertain to the design process for an on-bridge BMP retrofit. This means that nearly every BMP retrofit project will be a unique design process that requires contributions from multiple departments and disciplines.

When considering all the aspects that go into retrofitting a bridge for stormwater treatment, the questions of what is “inside the box” (i.e., the details of the BMP itself) and how it is configured are secondary factors as compared to placement, configuration, and general sizing on the bridge. Through this broader design process, we have developed a better understand of the requirements for the BMP itself in order to be feasible and practical in on-bridge stormwater treatment retrofit applications.

Overall, our work reinforced the findings of NCHRP Report 778, specifically that on-land BMP placement is far preferrable than on-bridge placement. Any on-bridge option is likely to involve highly custom designs, especially for conveyance and mounting/access of the BMPs that requires extensive effort to analyze various constraints and configure project-specific design elements. However, through this initial design assessment, we began to develop a systematic way of approaching design questions and a prioritization of design considerations. This became the foundation of the systematic approach included in the Guide.

Task 2 Findings: Candidate Media Blend, Prototype BMP, and Research Plan (Interim Report 1)

Interim Report 1 included a synthesis of design recommendations for the candidate filtration media and BMP. This was based on the evaluation of stormwater treatment processes (Task 1a) and the review of overall stormwater treatment design (Task 1b). The following primary findings were produced via this synthesis.

Recommended Candidate Media for Testing

Interim report 1 identified a candidate media for testing in Task 3. The recommended media was modeled after recent testing in Washington State (Table 3).

Table 3. Media component recommendations

| Component | Fraction of media blend by volume |

|---|---|

| Washed Sand | 60% |

| Coconut Coir Pith | 20% |

| Granular Activated Carbon | 15% |

| Activated Alumina | 5% |

Media components were described in the Task 1a memorandum in sufficient detail to support procurement. A summary of rationales is below:

- This blend exhibited excellent performance under high flowrate conditions using real highway stormwater runoff. It has demonstrated performance for metals and nutrients. Based on physical properties is expected to provide co-benefits for other pollutants, including toxic organic compounds.

- The media permeability is high, which is expected to provide resistance to clogging and support high filtration flow rates. We believe a design flowrate of 50 inches per hour will be supported pending Task 3 lab confirmation.

- It is composed of materials that are readily available in Washington State now and can be substituted with local materials or shipped to other regions from Washington State.

- Biochar has been used in Western Washington studies in place of granular activated carbon. However, it is unclear whether material of the same quality is available throughout the country. Additionally, this material is less standardized than other treatment media. For the candidate filtration media, granular activated carbon is recommended. This material is more standardized, less friable, and has demonstrated treatment effectiveness. It serves a similar role to biochar.

- This blend extrapolates only slightly from what has been tested. Incorporating activated alumna into the media (as opposed to a separate layer, as tested in Washington State) may have somewhat different effects than use as a polishing layer but should not significantly impact permeability. Additionally, performance of blends without the polishing layer was still strong for metals.

- Ongoing field testing of a similar media blend was being performed by the City of Bellingham as part of TAPE certification efforts at the time of Interim Report 1. This effort has since completed and demonstrate that this blend offers strong performance at 60 inches per hour.

Key data gaps for this option included:

- The expected treatment performance needed to be validated at elevated media flowrates, nominally at least 50 inches per hour to support feasibility in the bridge environment.

- Testing was needed to determine the relationship between sediment loading expected in bridge runoff and hydraulic conductivity to be able to assess potential maintenance intervals.

- Material availability, quality control, and cost needed to be better defined.

We also recommended providing a menu of proprietary media blends that can be used in the prototype BMP design. Key rationales include:

- Treatment performance has been rigorously evaluated meeting TAPE certification requirements.

- Blends have been specifically designed to operate at high treatment rates.

- Information is available about O&M frequencies.

- Vendors perform quality control of media component, making this simpler for DOTs or their contractors to source for construction and for DOT O&M departments to source for ongoing replacement cycles.

- Bulk material can be obtained from at least three vendors for use in bridge-specific treatment devices, therefore the use of this media may be feasible without triggering sole source procurement policies.

Proprietary filtration media were not tested in Task 3 as they have already undergone TAPE testing. Further research into these media was completed as part of Task 5 and included in the Guide.

Chapter 3 of the Guide includes template specifications for the recommended media blend and also includes a summary of proprietary media options.

Development of Candidate Prototype BMP Design

While overall BMP retrofit projects will be influenced by many project-specific considerations, DOTs may benefit from standardization of some elements. In particular, standardizing and testing a prototype BMP design would support a greater level of certainty in treatment performance, sizing, constructability, and O&M procedures. It could also streamline the design process for DOT teams, particularly by providing BMP design templates and parameter guidelines tailored to the bridge environment.

This section pertains to what we refer to as “the box” in the sections above. This does not pertain to placement, structural connections, or conveyance connections as we believe these design factors will be challenging and potentially undesirable to standardize between bridges. However, the constraints posed by these factors have strongly informed the protypes developed.

Based on the findings of Task 1a and 1b we have distilled the following design requirements for the BMP component of the treatment system (Table 4). For each, we summarized the rationale, assessed relative importance, and identified the preliminary design decisions to address each requirement.

Table 4. Design Requirements and Rationales for BMP Design

| Preliminary Design Requirement | Rationale for Design Requirement | Relative Importance | Preliminary Design Decisions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provide 18 to 24 inches of media depth and 6 inches of head space. |

|

H |

|

| Avoid patented or complicated flow conditions. |

|

H |

|

| Support project-specific sizing based on local rainfall, loading, and tributary areas. |

|

H |

|

| Ensure that fully clogged media will not interfere with bridge drainage. |

|

H |

|

| Minimize weight |

|

M/H |

|

| Minimize time of bridge lane closure for maintenance. |

|

M/H |

|

| Keep design simple, using readily available components |

|

M/H |

|

| Preliminary Design Requirement | Rationale for Design Requirement | Relative Importance | Preliminary Design Decisions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Address cold climate operational issues including deicing grit, salts, and freeze-thaw |

|

M/H |

|

| Provide pre-settling and oil-water separation component |

|

M |

|

| Balance high permeability with treatment performance. |

|

M |

|

| Avoid the need for manual hand labor over the side of the bridge. |

|

M |

|

| Avoid need for unusual, task-specific equipment |

|

M |

|

| Design the BMP with flexibility to use in multiple locations on the bridge, assuming it would be placed on a structural rack. |

|

M/L |

|

H = High (must have); M = Medium (very good to have); L = Low (nice to have)

Discussion of Major Design Decisions

The following sections outline our thought process for major design decisions.

Role of Pre-treatment

Pre-treatment serves three main purposes in the highway environment in general:

- Provides a place for capture and storage of bulk material, such as trash, leaf litter, and deicing grit, so it does not interfere with system hydraulics (e.g., obstruct piping) or induce media clogging.

- Remove oil and other floatable materials. Oil and other floatable materials can be skimmed fairly readily in a pre-treatment system to reduce the effect of this material on media bed longevity. Would have the benefit of minor spill control as well.

- Remove suspended solids. While pre-treatment options within a small footprint offer relatively little time for settling and are expected to have little effect on most suspended particles, there could be some removal of suspended solids.

In typical highway drainage systems, the role of pre-treatment is distributed between inlets (often with sumps), shoulders, ditches, and/or the forebay of BMPs. However, most bridge drainage systems have no catch basins or sumps upstream. Therefore, unlike a traditional highway drainage system, the BMP will receive the full load of materials coming from the highway. Additionally, in locations where traction sand is used, it may be applied more frequently on bridges due to their greater susceptibility to freezing. For these reasons, we recommended including pre-treatment. The ability to settle a significant portion of suspended solids in a small footprint is minimal, however a pre-treatment forebay targeting bulk material, traction sand, oil, and other floatable material would likely improve the lifespan of the BMP enough to justify the added weight and space. We developed two prototype designs, one with a separate forebay module and one with an integrated forebay module.

Approach for Media Rehabilitation and Replacement

Initial sizing and clogging estimates (Task 1b) suggest that media rehabilitation or replacement will likely be needed annually or more frequently in many cases. Therefore, the approach for media rehabilitation or replacement is an essential consideration in the design of the BMP. We considered three primary O&M paradigms as summarized in Table 5.

Table 5. Design paradigms to support media rehabilitation and replacement

| Paradigm | Rehabilitation Activities | Replacement Activities |

|---|---|---|

|

Pre-treatment chamber is vacuumed in place via a vactor truck. Mulch and media surface are scraped, removed, and replaced with like materials. This likely requires hand labor with media carrying vessels such as sacks or buckets. In some circumstances perhaps a vactor truck could be used. |

The full depth of media is removed, potentially by hand labor or a vacuum truck. Underdrain piping is rehabilitated in place, if needed. New bulk media is installed, potentially via emptying sacks or buckets. |

|

Pre-treatment chamber is vacuumed in place via a vactor truck. Spent packages are removed and replaced. Crews handle packages instead of loose media. |

All packages are removed, likely by hand labor. Underdrain piping is rehabilitated in place, if needed. New packaged media is installed. |

|

Optionally, crews can maintain the surface in-situ as in Paradigm 1. Optionally, crews can remove the modules and replace with a new module, then perform rehabilitation at a maintenance facility. |

Crews can remove the module and replace with a new module, then refurbish the removed module at a maintenance facility. At the maintenance facility, bulk media is dumped, underdrain is rehabilitated, as needed, and new media is loaded. This can mostly be performed with equipment. |

Of these options, we do not recommend Paradigm 2 for non-proprietary designs. Some vendor technologies (e.g., Contech’s Stormwater Management StormFilter®) include patented cartridge designs that align with Paradigm 2. However, it is unclear whether simple sacks or pillows procured by a DOT would provide treatment while maintaining permeability and limiting short-circuiting. This would require substantial design iteration, beyond what can likely be funded in this project.

Paradigms 1 and 3 are both viable relative to treatment performance and procurement but are much different for maintenance procedures. Of these, we recommend a combination of Paradigm 1 and Paradigm 3. This would substantially reduce the duration of lane closures and reduce the need for manual labor over water. We expect routine maintenance on an annual basis, and full media replacement to occur every 3 to 10 years. So, it would benefit DOTs to have an O&M procedure that can mostly be performed by equipment with lesser durations of lane closure per event. Additionally, this paradigm would still allow DOTs to perform in-situ maintenance at intermediate events if this is determined to be more cost effective than removal of the module.

Paradigm 3 requires a greater upfront cost for replacement systems, therefore if capital costs are more important than O&M costs and impacts for a given project, then this paradigm may not be desirable. It also may require heavier lifting capabilities than supported by typical O&M equipment. Both of these factors justify more research.

The prototype design described below is designed to support Paradigm 3 (removable) but would allow DOTs to operate it per Paradigm 1 as well.

Role of Proprietary Technology

There are several vendor-supplied proprietary media products that have been tested and vetted to meet design objectives within a compact footprint. This represents a major investment in product development and testing undertaken by these companies, well beyond the level of funding available in the current research project. As such, we found that it is worthwhile to consider the role that proprietary technology could play in meeting DOT design objectives. Options for incorporating proprietary technologies into designs were included in the Guide.

Prototype Treatment System Designs

Based on the design analysis presented in Table 4, we developed prototype BMP conceptual designs to support further design development. These designs were configured to meet most of the design requirements in Table 4.

The primary design elements and their justification are:

- A metal support rack is custom designed for each project, including necessary structural analysis to support this design. The metal support rack is installed independently of modules.

- The treatment system is modular, including modules that can be lifted and removed in their entirety and replaced with a fresh module. The removed module would be rehabilitated off-site after the maintenance event. Optionally, in locations with suitable with access, some routine maintenance could be performed in-place between rehabilitation events.

- Treatment modules are formed from steel-supported high-density polyethylene (HDPE) tanks, fiberglass tanks, or other lightweight materials with adequate strength in readily available sizes.

- Pre-treatment is provided via a simple sump design with baffles and a downturned elbow to retain floatable materials and scum.

- Flexible rubber couplings allow efficient connection and disconnection of piping between modules and allow tolerance for modules to be imperfectly aligned. Crews would need to disconnect couplings to lift units, then reconnect couplings after new units are lowered into place.

- The design is based on a single point of inflow to each series of treatment units, reducing the need to design a distribution header. For systems with several modules, a distribution header is an option that could be considered by project designers.

- Most modules could have the same design and can be interchangeable when replaced for maintenance. Terminal (first and last) modules may have different designs than intermediate modules. Alternatively, modules may be nearly identical with caps placed over unused connections.

- Each module has a slotted PVC well screen underdrain at the bottom, designed with slot size to convey the design flow and resist clogging from particles found in the media.

- Consider an outlet control valve and/or orifice is affixed to the well screen underdrain to control the rate of flow of water from each module if media will have permeability above the design rate. Each module drains independently.

- Media is filled around the well screen up to a depth of 18 inches and is topped with shredded, non-floating mulch to resist clogging.

- A thin concrete splash pad is used at locations with concentrated flow; mulch may be desirable to resist scour and filter sediment.

- The terminal module has an overflow pipe that controls the water level in the system.

- An optional gutter system below the modules can collect water if it must be routed to a piped conveyance system or its drop point moved.

- Optional side cover and roof lid provide a visual and ultra violet light barrier but would not need to contain water. These could be hinged.

Prototype BMP designs are described in Chapter 3 of the Guide including design schematics. To avoid repetition, we do not reproduce the same information here. Please see Chapter 3 of the Guide for the ultimate recommended prototype BMP and associated justification for design elements and decisions.

Key Data Gaps and Research Priorities

The final outcome of Task 2 was the identification of key data gaps and research needs to advance the prototype media and BMP and support the development of evaluation and design guidelines. As part of this task, we identified data gaps for the prototype BMP design and provided an initial assessment of the relative importance of each data gap for developing the design and guidelines (Table 6). This assessment of research needs informed the Task 3 research strategy.

Table 6. Assessment of data gaps for BMP design development

| Data Gap | Rationale/Discussion | Priority for Design and Guidelines | Addressed in Task 3 Research Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment performance of the Western Washington media at 50 inches per hour | This media has not been fully vetted at this flowrate. | Medium – good reasons to expect adequate performance but need to confirm. | Yes, via WQ testing |

| Treatment performance of proprietary media without plants | We believe the removal mechanisms for dissolved metals would be largely unaffected, however this has not been tested. | Medium – good reasons to expect adequate performance. | No |

| Treatment performance of media in the specified configuration. | The prototype BMP would have a similar configuration to what has been tested, but with some differences. | Low - This is a relatively minor consideration as similar media depths and loading rates are provided. | Not directly but designed the water quality column study to match loading and contact time. |

| Performance for emerging contaminants | Testing of blends has primarily included conventional parameters. Performance for emerging contaminants may be valuable. For example, researchers have recently identified 6PPD-quinone as a key cause of salmonid mortality in some species. | Medium – Metals performance is only a subset of total BMP effectiveness to reduce toxicity. | Yes, evaluated 6PPD-quinone. |

| Performance for toxicity reduction | The relationship between toxicity and metals is not direct. For example, media could change the speciation of stormwater in a way that makes it less toxic without necessarily removing metals. | Medium – Metals performance is only a subset of total BMP effectiveness to reduce toxicity. | No |

| Data Gap | Rationale/Discussion | Priority for Design and Guidelines | Addressed in Task 3 Research Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maintenance interval due to clogging and the relationship between sizing and clogging interval | This has not been assessed for the Western Washington media directly but has been assessed for similar media. Methods of testing this for the proprietary media differ and may not be comparable. The use of traction sand in some cold climate areas may be an important factor influencing sediment loading and maintenance interval. Sand accumulation in pre-treatment may require more frequent cleanouts. If traction sand is ground down to finer particles, these could pass through pretreatment and contribute to clogging of the media bed. |

High - Due to cost and complexity of O&M, good information on clogging intervals is needed. Solids in the inflow need to be characteristic of bridge runoff | Yes, via permeability and clogging study. |

| Cost and availability of media with adequate quality control | The ability to procure quality-controlled media is most critical. Cost is of interest but may not be a key factor given small volume of media as compared to both construction and maintenance costs. | Medium - Availability of quality-controlled media is a primary issue. | Partially, via pilot procurement and media research. |

| Lifting capacity of equipment | The capacity of equipment for vertical (hoist) and horizontal (forklift) lifting options would influence the size of module that is allowable. Additionally, the availability of equipment that could lift from the side using forklift guides or similar would influence whether this design can be installed below the bridge deck. | High - This is important to confirm viability of BMP locations and guide module dimensions. | Yes, via preliminary equipment research. |

| Structural integrity of typical edge barriers to support weight, or ability to strengthen existing barriers. | This design paradigm is dependent on being able to attach the BMP mounting rack to the edge barrier. Edge barriers vary greatly from bridge to bridge, and it is clear that strength is not always adequate. However, we need to confirm that this option has reasonable applicability and options for strengthening barriers that are deficient. | Medium - This is important to confirm viability of BMP locations and guide maximum weights. | Partially, via guidelines for scoping structural analysis and research into edge barrier strength ratings |

| Data Gap | Rationale/Discussion | Priority for Design and Guidelines | Addressed in Task 3 Research Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specifics of connections and configurations | More detailed research into available fittings and materials can support further design development. As part of this, we need to understand the tolerances of fittings to allow some imprecision in how modules are placed. | Low – This can be developed in guidelines; does not require testing. | No |

| Confirmation of full-scale hydraulics of system | The hydraulic capacity can be reasonably calculated using standard hydraulic methods. However, it would be useful to test the system with the media, underdrain system, and outlet control to confirm hydraulic function per design. | Medium - This is confirmatory only. We expect calculations to be close enough. | No |

| Structural design requirements | Additional research is needed to determine the viable options for lifting modules, such as lifting lugs or straps. | Medium – This is important but is likely to depend on hoisting equipment used. | No |

Task 3 Findings: Laboratory Testing and Supplemental Research

Media Procurement

Interim Report I described a recommended filtration media for testing. As an intermediate outcome of Task 3, Geosyntec sourced the recommended filtration media from Walrath Landscape Supply company in Tacoma, Washington. Based on our assessment, products similar to these are likely available in most parts of the country; shipping would be needed for some materials. Appendix C contains additional information on these products. More detailed specifications are included in the Guide.

Permeability and Clogging Results

The methodology and results of the permeability and clogging study are documented in Appendix C to this report and summarized below.

Results and Interpretation

The candidate filtration media was installed in a one-inch diameter permeameter in lifts of about four inches for a total of 18 inches. Permeability was then measured for the new media using a falling head test. The permeability (K) was calculated as follows:

Where:

K = Permeability

L = Length of the media

h1 = Water level at the beginning of the test measured from the base of the media

h2 = Water level at the end of the test

t = time for water level to fall from h1 to h2

Stormwater solids were collected from the bottom of a hazardous material trap (HMT) located in a stormwater basin receiving exclusively highway runoff. Subsequent permeability measurements were conducted after the equivalent of 0.5 lbs/ft2 (1.2 gm per column) of sediment was added to each column.

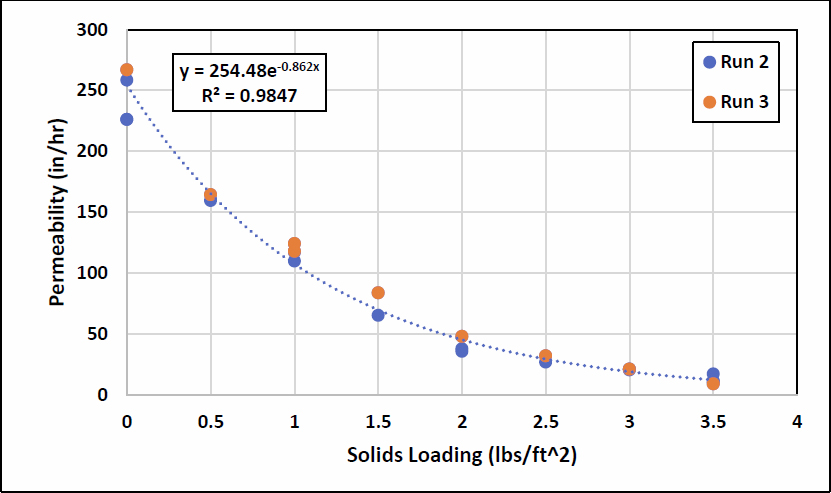

Run 1 experimented with various methods of dosing the column with solids, so the results are not very consistent. It appeared that accelerated aging provided reasonable results, so that method was used in Runs 2 and 3. Since they used the same methodology and produced similar results the results of both runs were plotted on the same graph and a trendline developed that used both data sets. These results are provided in Figure 2.

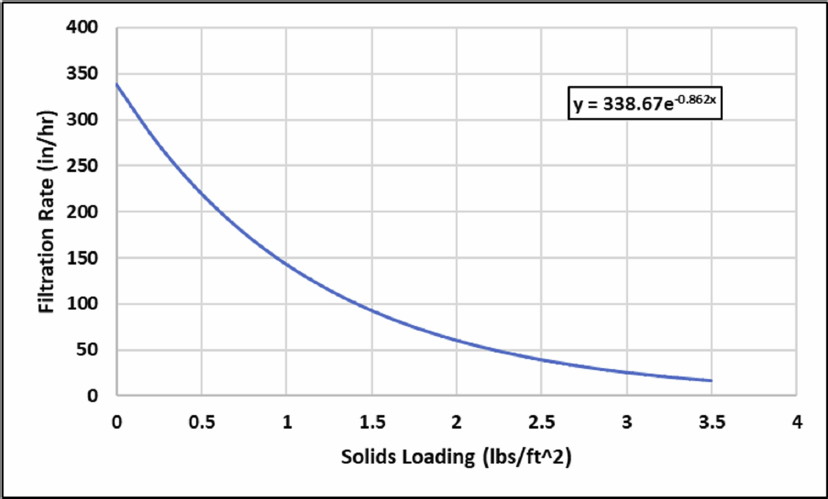

The permeability for Runs 2 and 3 was then converted to filtration rate using Darcy’s Law,

Where:

q = Filtration rate

K = Permeability

dH = Water column length (media depth + height of water above media = 24 in)

dL = Media depth (18 in)

The media filtration rate as a function of solids accumulation is shown in Figure 3. This assumes eighteen inches of media and a six-inch water depth over the media.

Failure (K < 19 in/hr equivalent to a filtration rate of 25 in/hr) is predicted to occur with a suspended solids loading of about 3.3 lbs/ft2. A decline to 50 in/hr of media filtration rate occurred at around 2.2 lbs/ft2.

Comparison to Similar Clogging Studies

Table 7 presents a comparison with previous clogging studies. What makes an accurate comparison difficult is that there is no standard testing protocol or agreement on what constitutes “clogged”. As one can see in the table below that the final value of permeability as a percent of the initial value varies substantially. However, agreement between these studies is fairly strong given the range of variables that can affect clogging process.

The most similar study is that by Kandra, et al. (2014) even though the solids used in their experiments contained substantially larger particles than in this study. They found that the rate of clogging varied somewhat by filtration media characteristics, but the dominant factor seemed to be filtration rate with the most rapid clogging associated with the highest flowrates.

Table 7 Comparison of Solids Loading for Clogging

| Study | Solids Loading lbs/ft2 | % of Initial K at Conclusion | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| This Work | 3.34 2.25 |

8% 14% |

Clogged defined at 25 in/hr and at 50 in/hr |

| Kandra, et al. 2014 | 1.2 – 4.3 | 5% | Varied depending on media characteristics |

| Barrett, et al. 2013 | 2.5 | 16% | K relatively constant and columns not clogged |

| Pitt, et al. 2010 Pitt and Colyar 2020 | 2 – 2.5 | 17% | Lab with field verification |

| Study | Solids Loading lbs/ft2 | % of Initial K at Conclusion | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fairbaugh 2022 | 1.9 | NA | Water with TSS, organic matter and motor oil (7 mg/L). |

| NAS, 2019 | 1.9 | 25% | Clogged defined as 50 in/hr |

Biofouling of media beds has been observed as a hydraulic failure mechanism, particularly where seasonal rainfall maintains continuously wet conditions (personal communication, Jim Lenhart). This study included accelerated aging and did not attempt to simulate the full loading conditions found in the highway environment. Therefore, the scope of this study did not support evaluation of potential biofouling.

It should be noted that the influent to the columns did not include large debris, coarse solids, traction sand, or floatable sheens of oil and grease, or other material that can clog media beds. Pre-treatment via a settling chamber and downturned elbow for floatable material exclusion is typically effective to remove much of these components and reduce the variability of stormwater influent. The results should be applied to designs where pre-treatment is provided.

Overall, we believe the findings of past studies are all relatively similar, and the findings of this study are generally comparable to previous studies. While there is significant uncertainty in the lifespan of media associated with variability in stormwater characteristics, loading rates, and other factors, our clogging tests show that this media is similar to prior high-rate media tests with respect to its susceptibility to clogging.

Water Quality Testing Results

The methodology and results of the water quality treatment study are documented in Appendix D to this report and summarized below.

Experimental Setup

The selected filtration media was placed in either one-inch diameter PVC columns or a 7/8 in diameter Teflon column that were 18 inches in length. Stormwater collected from a hazardous material trap (HMT) located in a stormwater basin exclusively receiving highway runoff from Loop 360 in Austin, TX was used as the source water for the column experiments. Stormwater was collected at two times. The first was on 1/25/23 when 1.16 inches of rainfall was reported. The second sample was collected on 4/21/23 after a storm event of 0.94 inches. Both of these events occurred during periods of normal rainfall and prior to the drought conditions Austin experienced during summer 2023. The stormwater was placed in a series of 5-gallon buckets and stored at 4 C prior to use. Stormwater from the first sampling event was used for the first three experiments and stormwater from the second sampling event was used for the final experiment.

The column setup consisted of three parallel column trains with two intermediate sampling points and one final effluent sampling point in each column train as shown Figure 4. The alphabetic identifiers indicate the different parallel columns. The numeric identifiers indicate the intermediate and final effluent from each column. For example, A3 is the final effluent from the A column. A single influent sample location provides the representative influent for the overall system. Samples were collected at the influent, effluent (i.e., A3, B3, C3) and intermediate sampling points (i.e., A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, C2).

Removals of dissolved zinc, copper, ortho-phosphate and 6PPD-quinone in a system with a high loading rate of 50 in/hr were compared to removals at more typical loadings of 14 in/hr. Washington State Technology Acceptance Protocol Ecology (TAPE) treatment standards for dissolved metals were used as a benchmark for evaluating performance.

For columns operating at 50 in/hr, we dosed the equivalent of approximately 1 year of runoff to the columns, which is about 4,000 inches treated through the column footprint (i.e., equivalent to a column of water 4,000 inches tall over the footprint of each column). This is based on a representative sizing factor of 300 sq-ft of media bed per acre treated with an average precipitation depth of 30 inches per year. For the columns operating at 14 in/hr, we treated the equivalent of approximately 3-4 months of runoff, which is equivalent to about 1,400 in of runoff dosed in the first series of experiments and approximately 1,200 inches of runoff in the second.

Four separate analyses were conducted of the raw water. Table 8 shows the parameter values observed. Variations in the concentrations are attributed to deviations among the buckets of water stored. As noted above, these analyses were performed on settled water with relatively little suspended material remaining, so it is expected that dissolved and total metals and phosphorus values will be similar. The increase in pH and ammonia and decrease in nitrate suggest that some biological activity occurred during storage of the water in the 4°C constant temperature room.

Table 8 Influent Water Quality for the Column Experiments (Pre-Settled)

| Parameter | MRL | Raw Water 1 | Raw Water 1 | Raw Water 1 | Raw Water 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.33 | 7.96 | 7.99 | ||

| Alkalinity (mg/L CaCO3) | 20 | 60.8 | 51.2 | 52.9 | 57.7 |

| Ammonia Nitrogen (mg/L as N) | 0.02 | 0.0319 | 0.0655 | 0.256 | |

| Calcium Total (mg/L) | 0.2 | 35.5 | 29.2 | 29 | 31.3 |

| Calcium Dissolved (mg/L) | 0.2 | 25.9 | 28.3 | ||

| Magnesium Total (mg/L) | 0.2 | 1.87 | 1.91 | 1.75 | 1.87 |

| Magnesium Dissolved (mg/L) | 0.2 | 1.68 | 1.84 | ||

| Iron Total (mg/L) | 0.05 | ND | 0.185 | 0.0586 | 0.136 |

| Iron Dissolved (mg/L) | 0.05 | ND | ND | ||

| Copper Total (mg/L) | 1 | 0.012 | 0.00932 | 0.0086 | 0.017 |

| Copper Dissolved (mg/L) | 1 | 0.00748 | 0.0093 | ||

| Zinc Total (mg/L) | 1 | ND | 0.0514 | 0.0274 | 0.0651 |

| Zinc Dissolved (mg/L) | 1 | 0.0411 | 0.0302 | ||

| Total Phosphorus (mg/L as P) | 0.02 | 0.236 | 0.103 | 0.0796 | 0.0605 |

| Ortho-Phosphate (mg/L as P) | 0.01 | 0.2 | 0.0441 | 0.0439 | ND |

| Nitrite/Nitrate (mg/L as N) | 0.02 | 6.12 | 1.18 | 0.788 | |

| Total Organic Carbon (mg/L) | 0.5 | 7.13 | 8.7 | 8.85 | 8.51 |

| TOC, Dissolved (mg/L) | 0.5 | 7.48 | 8.47 | 8.6 |

Dissolved Metals Removal Results

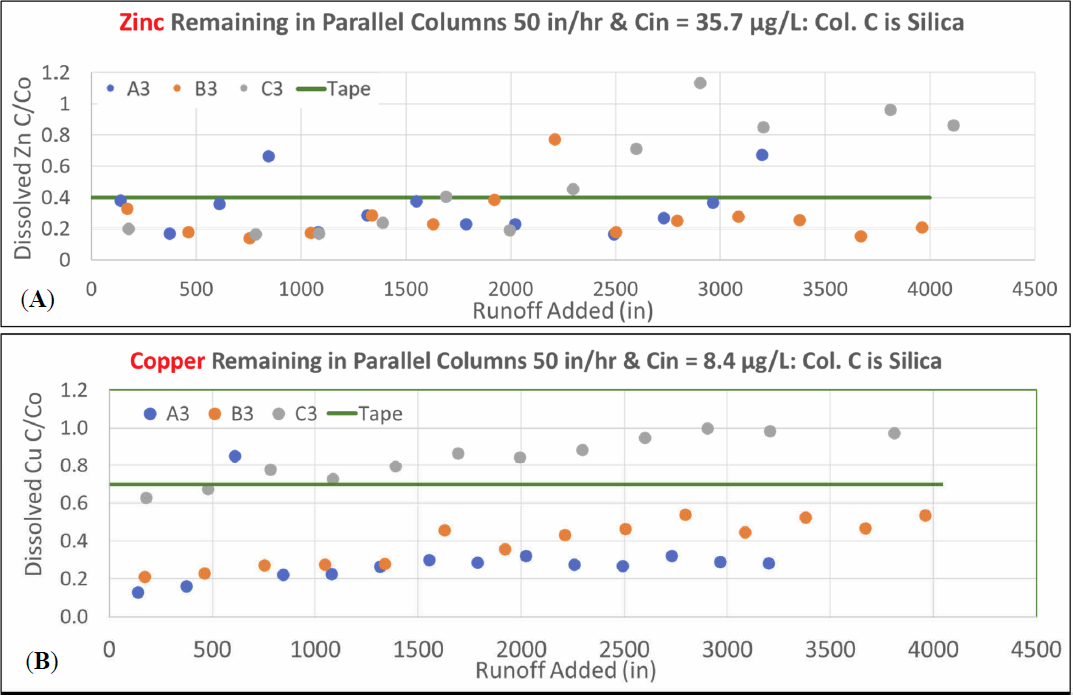

Removal of copper and zinc met TAPE benchmarks for the column effluent (measured at A3, B3 or C3) for columns packed with the recommended filtration media; although, in several columns an initial acclimation period was required for the first few hundred inches of runoff of both the 14 in/hr and 50 in/hr loading rates. Representative results for the removal of dissolved copper from intermediate and effluent sampling points for column B of the three parallel columns are shown in Figure 5. While the dissolved copper remaining is higher for the 50 in/hr and the intermediate columns exceed the TAPE benchmark of 30 percent removal, the effluent from both 50 in/hr and 14 in/hr meet the TAPE requirements.

Figure 6 provides a comparison of the 50 in/hr effluent copper and zinc concentrations remaining from the three parallel columns in which columns A and B are packed with the recommended filtration media and column C is packed with silica sand. The silica sand serves as a baseline non-adsorbing media and the data reflect that both copper and zinc concentrations exceed the TAPE standard with this media. In contrast, both copper and zinc meet the TAPE standards at the higher loading for most of the samples; however, the last data point for the A column exceeds the tape standard. This column was the only one of the three triplicate 50 in/hr loading rate columns where we observed breakthrough beyond the TAPE standard. Moreover, that data point was significantly higher than the total zinc concentration measured by LCRA for the same sample; if the total zinc concentration of that sample is used to calculate removal, then the effluent easily meets the TAPE benchmark.

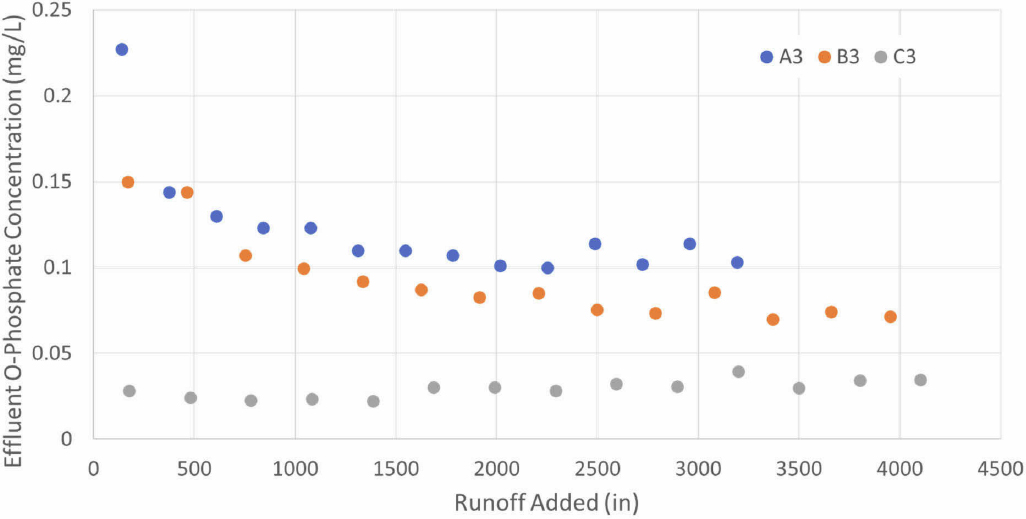

Phosphorus Removal Results

This study employed pre-settled stormwater; thus, it is likely that much of the particulate phosphate had been removed from the influent source prior to the experiments. In some runs, the relatively low concentrations of dissolved ortho-phosphate led to dissolved phosphorus export from the media as shown in Figure 7. In this 50 in/hr loading experiment, the initial concentrations of ortho-phosphate in the final effluent from the column trains containing the recommended filtration media (A and B) are significantly higher than the influent concentrations and decrease over the course of the experiment. These results are consistent with results reported for the other two column experiments with low influent ortho-phosphate concentrations. However, for the experiment in which the ortho-phosphate concentrations were high (200 ug/L), the removal was also high (55 percent). As a result, it appears that there are components of the media that are capable of removing significant amounts of dissolved phosphorus while other components are prone to leaching minor amounts of phosphorus when influent concentrations are low.

While this study did not consider particulate removal (stormwater was pre-settled) effective removal of particulate-bound phosphorus by the media bed under would likely offset the minor increase in ortho-phosphorus and result in substantial positive removal of phosphorus. Table 9 summarizes likely ranges of total phosphorus removal for the media. Additionally, replacing coco coir pith with zeolite would further reduce potential phosphorus sources. This recommendation is included in the Guide for cases where nutrients are a pollutant of concern.

Table 9. Estimated Total Phosphorus Removal

| Particulate P | Dissolved P | Total P | ||

| Typical Highway Influent, mg/L | 0.32 | 0.12 | 0.44 |

TP concentration from NCHRP Report 778 from Highway Runoff Database (Granato and Cazenas, 2009) Particulate-bound fraction (60 to 80%) from WERF, 2011 |

| Estimated Effluent Quality, mg/L | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.22 | Particulate: Based on TSS removal from NCHRP 778 Dissolved: 0 to 0.05 mg/L increase, estimated from this study when concentrations are moderate. |

| Removal Fraction | 85% (removal) |

-40% (export) |

50% (removal) |

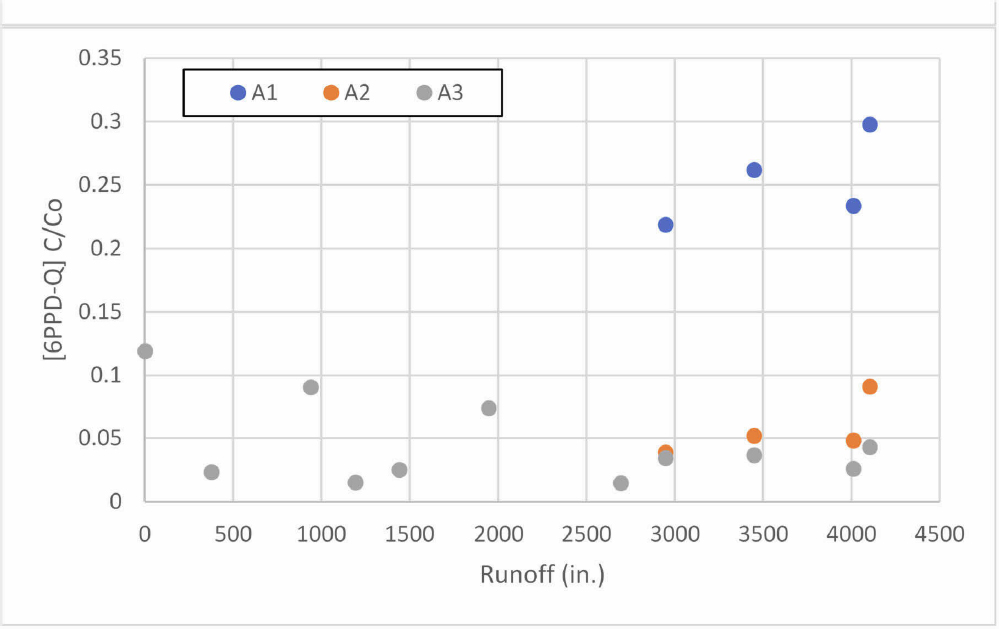

6PPD-quinone

The column experiment conducted in the Teflon column also included 6PPD-quinone spiked to an expected final concentration of 0.53 ug/L. The analytical method developed for this compound at the University of Texas had a method detection limit of 0.011 ug/L and a preliminary adsorption isotherm showed that the adsorption to the recommended filtration media followed a linear isotherm with a linear partitioning coefficient of 16.67 L/g in the stormwater. The isotherm results support the potential for adsorption of the 6PPD-quinone and the column experiments shown in Figure 8 confirms this potential with over 90 percent removal of 6-PPD-Quinone and increasing removal for each column section from A1 to A3.

Summary of Water Quality Study Results

The results of the water quality column studies can be summarized as follows:

- Column studies with the selected media at 14 inches/hour confirmed the removal of dissolved copper and zinc documented in previous studies.

- Column studies at 50 and 63 inches/hour demonstrated removal of dissolved copper and zinc that exceeds the Washington Department of Ecology TAPE benchmarks, although the

- Dissolved phosphorus reduction was largely a function of influent concentrations, with more than 50 percent reduction when the influent dissolved concentration was at least 0.2 mg/L, but export occurred when influent concentrations were as low as about 0.05 mg/L. TAPE benchmarks for phosphorus are expressed as total phosphorus. The media performance is estimated to be similar to the TAPE benchmark when considering the effect of particulate removal.

- The media was able to achieve more than 90 percent removal of the 6-PPD-Quinone at 63 inches/hour loading rate through the study duration, which resulted in effluent concentrations well below the LC50.

concentration reduction was somewhat less for copper at the higher flow rates than was observed at 14 in/hr.

No breakthrough in dissolved copper and zinc was observed when 4000 inches of runoff was applied to the columns, which indicates that the adsorptive capacity of 18 inches of media is sufficient to treat the equivalent of at least 30 inches of rainfall at a sizing rate of 300 sq-ft media per acre of roadway treated.

Task 4 Findings: Synthesis of Laboratory Findings and Development of Sizing Guidelines (Interim Report 2)

BMP Design Parameters

The laboratory analyses produced confirmation of key variables that support BMP design.

Media filtration rate

Treatment performance of the selected media blend at 50 in/h meets TAPE benchmarks for dissolved copper and zinc and achieves high level of 6PPD-quinone removal. This supports a design media filtration rate of 50 in/h. Higher rates could be considered, but further increasing the design flowrate would reduce the media bed footprint, and it is likely that clogging would control the sizing of the media bed.

A media filtration rate of 50 in/h corresponds to a provided treatment of flowrate 0.0116 cfs per sq ft (0.51 gpm per sq ft).

This is consistent with findings from recently completed testing by the City of Bellingham, WA on a similar media, which was approved for 60 inches per hour (Washington State Department of Ecology, 2022).

Media bed depth

For the selected media, data from interim sampling points showed considerable improvement in water quality with each increment of depth through the media bed. The full 18 inches of depth was needed to consistently meet TAPE benchmarks. If treatment system weight is a critical factor, substantial removal could be achieved with 12 inches of media. However, testing shows that there would be compromises in treatment performance with a 12-inch media bed.

Loading to Initial Maintenance

Load to initial maintenance is a measure of the mass of suspended sediment that can pass through one unit surface area of the media filtration bed before the media filtration rate declines below the design rate. For the selected media, under the recommended media filtration rate of 50 in/h and assuming a system that includes a settling chamber for pre-treatment, the recommended load to clog for design purposes is 2.2 lb/sq ft. If the media is allowed to decline to 25 in/h, allowable load to clog is 3.3 lb/sq ft.

Integrated Sizing Methodology

Interim Report 2 proposed an integrated sizing methodology that considers both water quality treatment design standards (i.e., how much water needs to be treated) or O&M considerations (how long a filter will treat water at or above the design treatment rate before it clogs). In a given region or application, either of these factors could be the controlling factor in design.

The sizing methodology and input variables are provided in the Guide, Chapter 4, Step 2b. This methodology is not repeated here.

Task 5 Findings: Guide and Case Studies

The approach for preparing the Guide and case studies is summarized in Chapter 2 of this report. The direct results of this task are embodied in the Guide. Applicable supporting information is included in the Guide or in the preceding sections of this summary report. We do not have independent findings from Task 5 that are relevant to summarize in this report. However, Chapter 4 of this report does present overall conclusions from this research project.