Transit Agency Goals and Non-Traditional Performance Indicators Focused on Equity (2024)

Chapter: 4 Regional Case Examples

CHAPTER 4

Regional Case Examples

Case example sites were selected from a list generated via the literature review and project panel inputs. Ultimately, twenty agencies were identified, with nine of them prioritized as top choices due to their unique practices. After reaching out to the top choice agencies, five expressed interest and a willingness to participate in the case example process. As a result, a meeting with each agency was scheduled so that the synthesis team could collect information not already available via public resources (e.g., agency websites and previous research). These discussions followed a detailed discussion guide as presented in Appendix C, which is similar to, but more detailed than, the Survey/Research Chat Questions presented in Appendix B.

Three of the case examples (the DRT, MBTA, and Metro Transit) presented agency-wide goals and measures, and two others (Cecil Transit and Envida) presented service/mode-specific goals and measures. Following a brief introduction to the transit agency are the findings from each case study organized in the following sections:

- Agency Definition of Equity

- Institutional Structure and Governance

- Current and Potential Indicators

- Target Setting and Recent Performance

- Engagement and Responsiveness

- Planning, Programming, and Operations

- Funding and Financing

- Data Collection and Management

- Lesson Learned and Challenges

- Summary, Including Key Challenges, Notable Practices, and Lessons Learned

DRT

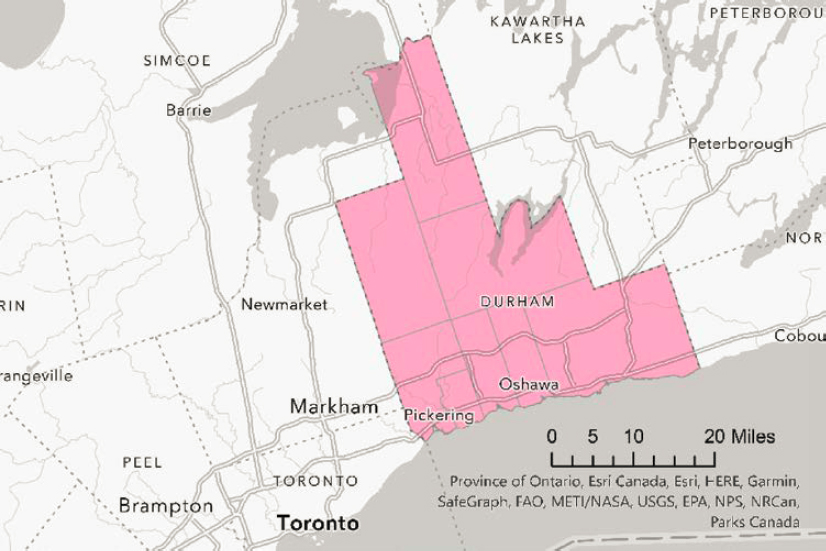

Since 2006, DRT has been the transit provider for the Regional Municipality of Durham (hereafter the “Region”), located east of Toronto, Canada, in the province of Ontario. Prior to the creation of DRT, each city or town in the Region was responsible for its own transit services. DRT operates scheduled bus service and On Demand (i.e., a shared ride service that uses smaller vehicles and dynamic routing where and when scheduled bus routes are not operating). Door-to-door On Demand service (paratransit) is also available for customers whose disabilities prevent them from using scheduled bus service. DRT service is available 24 hours a day every day of the week in urban areas and from 6 a.m. to midnight on weekdays and 7 a.m. to 9 p.m. on weekends in rural areas. Much of the funding for DRT services comes from property taxes, with the rest consisting of funding from fares, gas tax revenue, and reserve funds. Table 8 presents a summary of DRT’s 2021 performance, and Figure 1 is a snapshot of the transit agency’s service area.

Table 8. DRT service summary.

| Operating Statistic | Total |

|---|---|

| Service Area Size (Sq Mi) | 980 |

| Service Area Population | 696,692 |

| Modes Operated | Bus Demand Response On-Demand |

| Annual Unlinked Trips | 5,507,017 |

| Annual Vehicle Revenue Miles | 6,257,108 |

| Annual Vehicles Revenue Hours | 349,619 |

| Operating Costs by Revenue Source | |

| Fares | $16,914,391 |

| Municipal Funds | $54,717,067 |

| Provincial Funds | $8,630,915 |

| Federal Funds | $0 |

| TOTAL | $80,262,373 |

| Operating Cost per Trip | $14.57 |

Data Source: DRT

Image Source: Texas A&M Transportation Institute (TTI)

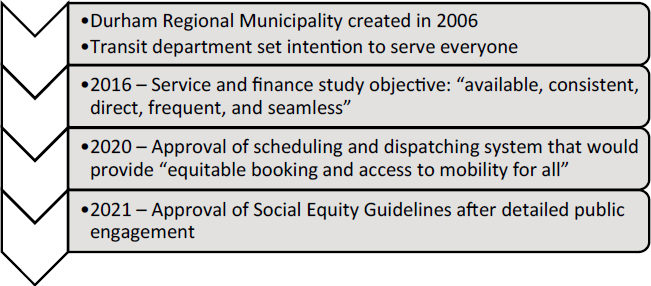

DRT was chosen as a case example because of the transit agency’s Social Equity Guidelines, guiding principles that put riders and their needs first, equity vision and buy-in at the decision-maker/leadership level, a regional commitment to provide transit to everyone, and a unique operating environment (consisting of everything from dense urban areas to vast rural areas). DRT’s Social Equity Guidelines combined with its service guidelines allow the transit agency to address transit equity comprehensively (instead of tokenized projects or groups) and in a manner that has garnered enough community support to earn additional property tax funding for the next 10-year funding cycle.

Agency Definition of Equity

According to DRT staff, the project’s definition aligns with how their transit agency approaches transit equity. However, instead of a definition, DRT has developed a public equity

statement—DRT’s Social Equity Guidelines—that outlines how the agency approaches equity in all aspects of transit (this statement was informed by a thorough internal process and approved by the governing council). The introduction to DRT’s Social Equity Guidelines is presented in Figure 2, and the complete set of guidelines are available at: https://www.durhamregiontransit.com/en/travelling-with-us/social-equity-guidelines.aspx.

Adoption of Equity Effort

When discussing these guidelines, DRT staff emphasized two of the agency’s guiding principles:

“Every customer trip counts.”

To ensure that people have basic mobility throughout the region, DRT uses different service models to meet different needs and to be as efficient as possible in its various operating environments. For example,

service is available 24 hours per day every day, but the type of service varies depending on where and when it is operating—fixed route service in dense areas and at times of high-demand and on-demand or demand response service in less dense areas and/or at times of low demand.

“We provide customer-centric integrated services that enable independent, spontaneous, and worry-free travel.”

DRT’s customer-centric approach helps ensure people have access to transit service the way they need it when they need it. For example, DRT knows and accounts for riders who do not use smartphones (or have mobile data); therefore, call centers are critical to ensuring everyone has access to real-time transit information and the ability to make trip requests. Additionally, the agency is committed to being proactive in their efforts to facilitate access to service. The Ambassador Team works to reduce barriers to service with one-on-one and group travel training to help riders become more comfortable using transit, and this service is available to anyone.

Institutional Structure and Governance

DRT was established under the DRT Commission in 2006 to provide transit service throughout the Region in the Province of Ontario in Canada. As such, the transit agency is governed by the DRT Executive Commission (the commission consists of the members of the Durham Regional Council and is led by the Regional Chair, who also holds the position of chair of the DRT Executive Commission). Prior to 2006, each city in the Region was responsible for its own transit services. According to DRT staff, strong commission- and council-level support exists for transit equity and efforts that ensure everyone in the Region has access to transit when they need it. DRT’s approach to providing comprehensive transit service throughout the Region stems from previous council commitments to provide paratransit service that exceeds the required minimums (similar to the United States, Canada requires accessible paratransit services in areas with scheduled fixed route service) and allows people with disabilities to freely travel throughout the Region.

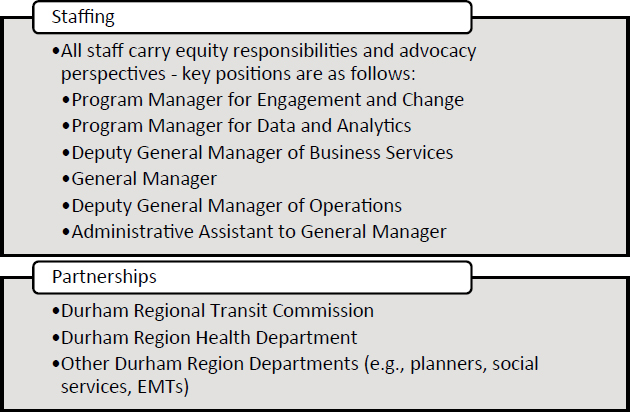

The council has empowered DRT staff to work within available budgets to ensure DRT meets its commitments to provide service throughout the Region that meets the various needs of the community. As such, everyone at the agency is expected to contribute to efforts to improve transit equity within their respective roles, so much so that DRT staff describe their approach as coming from an “advocacy perspective” when dealing with decisions that affect transit equity. This perspective means that vulnerable road users, sidewalk accessibility, pedestrian crossings, and other similar “complete trip” considerations related to accessing transit service are at the forefront of the agency’s thought processes and often influence their interactions with other agencies (e.g., working with the entity responsible for sidewalk infrastructure to improve conditions or providing comments via planning processes about how projects could better serve people). The advocacy perspective also guides DRT’s efforts to change the way people approach transportation conversations so that the focus is on people and not vehicles (e.g., pedestrian safety instead of vehicle throughput). Furthermore, DRT staff noted that equity is “part of the fabric of government now,” which helps the transit agency work with other departments within the regional municipality, such as social workers and the housing agency, and with social service organizations. One way DRT works with other departments of the regional municipality is providing service that mirrors or supports the objectives of other groups. For example, Vision Zero traffic safety work is a regional priority, and DRT works to include Vision Zero principles in its service planning and operations (e.g., siting of stops or driver training). Internally, the human resources department is well versed

in social justice hiring practices, helping DRT ensure its staff and decision-makers reflect the communities they serve.

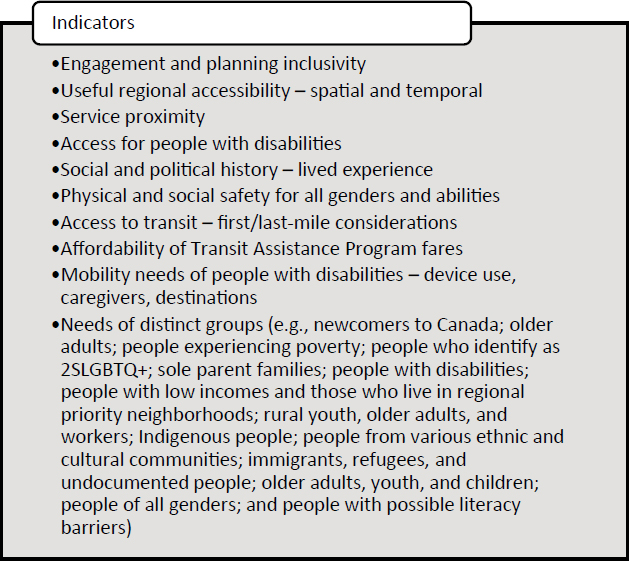

Current and Potential Indicators

DRT considers work on social equity to be a foundational part of its responsibility and something that is incorporated into all aspects of the agency. Therefore, DRT regularly reflects on the Social Equity Guidelines, and the transit agency’s service standards, to check whether the service that is available (or being planned) aligns with the expectations set forth in those documents. With that in mind, DRT puts forward its best efforts to prioritize based on other environmental pressures (i.e., service can only be rebalanced within the confines of the resources available to do so and without adverse impacts to other segments of the customer base). Additionally, DRT has established several social equity initiatives designed to help the agency provide the service people need and where they need it.

The Social Equity Guidelines exist to help the agency “ensure . . . decision making is evidence informed and considers a social equity focused approach to transit.” For example, the Social Equity Guidelines include the following commitments (DRT 2023c):

- Transit planners are expected to account for “transit realities and barriers” faced by equity priority groups, including newcomers to Canada; older adults; people experiencing poverty; people who identify as 2SLGBTQ+; sole-parent families; people with disabilities; people with low incomes and those who live in regional priority neighborhoods; and youth, older adults, and workers in rural areas. “It is imperative that DRT staff factor in these and other transit realities when planning transit services and incorporate a multiplicity of perspectives. This awareness can help develop and deliver services that are responsive and relevant to clients and communities and, ultimately, address unintended barriers within our transit system.”

- “We should . . . treat people the way they would like to be treated and avoid providing services based on our own preferences.” DRT states that the following groups require additional consideration during service planning: Indigenous people; people from various ethnic and cultural communities; immigrants, refugees, and undocumented people; lone-parent families; people with disabilities; people with low incomes; older adults, youth, and children; people of all genders; and people with possible literacy barriers. “In naming these equity priority groups; DRT acknowledges that these communities are not mutually exclusive. Individuals may self-identify as belonging to more than one group.”

- DRT will devote additional focus on the seven priority neighborhoods identified by Durham Public Health as ranking “poorly in terms or overall income, education levels, and employment.”

- DRT will review an equity checklist (see Table 9) during decision-making processes to “prompt important front-end considerations” and “think through and articulate how we’re integrating equitable and inclusive approaches into transit planning.”

DRT plans, monitors, and adjusts all services to adhere to simple service standards (DRT 2023b) as shown in Table 10 (emphasis added to highlight core equity concepts).

DRT’s social equity initiatives help the transit agency provide service that accounts for specific needs within the communities they serve. The initiatives include commitments to do certain

Table 9. DRT’s equity checklist.

| Category | Questions |

|---|---|

| People and Participation |

|

| Destinations, Routes, Vehicles, and Stations |

|

things (e.g., install transit shelters) as well as methods for adjusting service standards to account for the specific needs of specific groups. Table 11 presents all DRT’s social equity initiatives (DRT 2023c). Additionally, DRT tracks some specific measures related to transit equity outlined in Table 12.

Target Setting and Recent Performance

Because of the way DRT approaches transit equity—as a factor that is foundational to the service they plan and provide—the transit agency does not set targets for certain levels of performance

Table 10. DRT’s transit service standards.

| Standard Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Service Deployment | Residents of the Region can access transit services throughout the entire area from early mornings to late night seven days a week. How the service is delivered to an area varies by time of day and day of the week to ensure services are sustainable and implemented in an efficient and fair manner. |

| Ridership Productivity | As a base service, Demand Response service is provided when scheduled routes are unable to meet minimum ridership productivity targets. Ridership productivity targets are not applicable to the overnight network because the service provides mobility to groups of customers who may have no other travel option available. Each service type (e.g., PULSE, Base, GO Transit Connector, and rural) contributes differently to the DRT transit network, and each has unique minimum productivity targets. Route productivity varies based on the varying built environments in which each route operates. *Ridership standards are adjusted per DRT’s social equity initiatives to account for higher transit need in some areas—see Table 11. |

| Standard Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Service Frequency and Span of Service | DRT provides 24-hour transit service seven days a week in urban areas and service from 6 a.m. to 12 a.m. on weekdays and 7 a.m. to 9 p.m. on weekends in rural areas. The span and levels of service vary for each of the Demand Response zones and scheduled routes, which is based on customer demand. In the scheduled service network, the minimum service frequency is 30 minutes on urban routes and 90 minutes on rural routes. This scheduled service results in a customer waiting up to 15 minutes for a bus in the urban area and 45 minutes in the rural area. To ensure equity in scheduled service wait times, DRT deploys vehicles to ensure the time between a customer requesting a Demand Response trip and pick up achieves the following objectives: Urban areas: Customers will not wait more than 30 minutes for a pick up, with an average overall wait time of less than 15 minutes. Rural areas: Customers will not wait more than 60 minutes for a pick up, with an average overall wait time of less than 45 minutes. By 2025, all Demand Response customers, including current Specialized Services customers, will experience similar average trip wait times, including prebooked trips or trips scheduled in real time. The accommodated rate for trip requests made by eligible persons with disabilities will exceed 99.6 percent. |

| Service Proximity |

Service proximity means the walking distance between dwellings and the nearest bus stop. In the urban area, DRT aims to have:

|

Table 11. DRT’s social equity initiatives.

| Initiative Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Ridership Minimums in Priority Neighborhoods | The ridership productivity minimums influence the span and levels of service. The type of service and frequency planned for an area and shelter installations is based on ridership and boardings. For example, a bus shelter is considered at a bus stop recording 20 or more daily passenger boardings. In priority neighborhoods, recorded boardings and ridership will be increased by 50 percent to accelerate the deployment of bus shelters, moving from Demand Response to a scheduled service, and increase in service frequency during busier times of the day. For example, in a priority neighborhood, a bus shelter will be considered at a bus stop recording 15 or more daily passenger boardings. The ridership productivity guidelines for rural service already reflect a lower minimum average for boardings due to the lower density and greater distances traveled. |

| Service Design Guidelines | DRT leverages a monitoring framework to establish the type of service delivered (Demand Response or scheduled routes) and that the service is sustainable and efficient. |

| Transit Shelters | DRT will install shelters near locations such as retirement residences, hospitals, community centers, medical centers, and transfer stops. |

| Stations, Terminals, and Hubs | DRT’s Social Equity Guidelines will influence amenities and design at terminals by ensuring equity priority groups’ needs are met. Washroom designs will include gender-neutral facilities and spaces for infant changing and nursing. New initiatives will be implemented to improve access to electronic trip planning, information, and real-time information by considering Wi-Fi access through mobile devices, electronic customer kiosks, real-time information displays, and customer information lines. Wayfinding information will be improved and expanded, including the use of accessible formats. |

| Initiative Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Service Proximity |

A customer’s journey starts from their home, school, work, or other location and getting to the transit stop, hub, terminal, or station. Travel experiences will be improved by removing barriers and reducing distances to bus stops and hubs. DRT will work with regional and municipal partners to identify, address, and remove barriers to accessing transit services in their neighborhoods by:

|

Table 12. DRT’s transit equity measures.

| Measure | Description |

|---|---|

| Transit Assistance Program Average Fare per Participant | Tracks the average total fares paid by participants on a monthly basis compared to the total “value” of the trips taken to gauge affordability and/or usefulness for transit users with low incomes. The Transit Assistance Program (TAP) offers an unlimited monthly transit pass for eligible riders for $46.90 CAD per month. |

| Mobility Needs on Specialized Transit | Tracks the needs of each Specialized Transit (paratransit) customer, including use of mobility devices, support needed from drivers, and the presence of rider-provided attendants and trip purposes, to help DRT understand and account for riders’ needs over time. |

| Regional Connectivity | Checks the ability to travel from any location in the Region to a public transit mobility option in urban (900 square kilometers) and rural areas (2,200 square kilometers) of the DRT service area. |

| 24-Hour Urban Access | Checks that service gives access to transit within the service standards in urban areas any time of day on any day of the year. |

| On-Time Performance | Tracks whether the service provided adheres to the agency’s stated on-time performance standards. |

related to specific aspects of equity (e.g., availability of service in specific neighborhoods). Instead, the agency relies on its Social Equity Guidelines and Checklist to establish service that is inherently equitable throughout the Region.

Engagement and Responsiveness

DRT is kept abreast of community needs via multiple groups and engagement activities. The Transit Advisory Committee includes members from local cities within the Region, people with disabilities, and a dedicated equity advocate. This group meets three times per year to provide feedback to DRT about their plans for service. Via DRT’s UPass program, university decision-makers and student union representatives provide feedback on student needs. High school students with disabilities also have opportunities to gain work skills through the Project Search pilot program offered at the Region. DRT’s involvement in this program comprises providing travel training to participants, enhancing their independence, and making them more comfortable and confident in using public transit. DRT also hosts regular meetings with community partners and stakeholders, including dialysis patients, health professionals, children with developmental disabilities, groups that provide training and jobs for people with cognitive or developmental disabilities (DRT also supports these populations with travel training on a bus at their location), and targeted engagement sessions with specialized transit (paratransit) customers conducted in person and online. DRT’s customer service group works closely with community and social service organizations to facilitate access to fare products for people who either cannot afford transit or do not use smart phones by providing bulk passes via magnetic stripe paper passes. Similarly, DRT’s Transit Assistant Program offers reduced fares to people with certain income levels. This program is conducted in collaboration with the Regional Municipality social services department’s client teams (these groups conduct process applications and verify income).

Feedback from all groups is provided to the transit agency’s service design group so that they can integrate it into service planning. One example of the impact public feedback has had on DRT’s service is the recent change to the Transit Assistance Program. This program was initially envisioned as a fare capping program in which riders would pay per trip until a certain threshold was reached, at which point all further trips within the month would be “free” because the rider had spent enough money to obtain a pass product valid for unlimited travel. However, DRT learned multiple things about this program after conducting a program evaluation: Passes cannot be used on connecting services; therefore, people expressed that they were not getting as much value from the investment as they could, and users found the concept of fare capping confusing. Therefore, the transit agency shifted to providing a discounted monthly pass that users can choose to purchase at any time and receive unlimited trips on DRT and participating connecting agencies. Additionally, user and stakeholder feedback helped the agency develop both the Social Equity Guidelines and Service Guidelines, which resulted in more frequent service in priority neighborhoods and the introduction of 24-hour service throughout the Region every day of the year.

Planning, Programming, and Operations

As mentioned in previous sections, DRT’s Social Equity Guidelines and Service Guidelines mandate a minimum level of service throughout the Region, which dictates how service is planned and implemented. Additionally, the service must meet the following minimum equity-related requirements as presented in the Service Guidelines (these guidelines are also used to conduct ongoing service monitoring to ensure service reliability and availability):

- Scheduled routes will not operate at headways longer than 30 minutes nor for periods of the day shorter than three hours.

- Route performance will be regularly evaluated for modification, expansion into new service areas or service periods, or service reduction or transition to or from Demand Response.

- The span and level of service will be adjusted based on the customer demand for each route.

- Customers will not wait more than 30 minutes for a pickup in urban areas, with an average overall wait time of less than 15 minutes.

- Customers will not wait more than 60 minutes for a pickup in rural areas, with an average overall wait time of less than 45 minutes.

- By 2025, all Demand Response customers, including current Specialized Transit customers, will experience similar average trip wait times, including prebooked trips or trips scheduled in real time. The accommodated rate for trip requests made by eligible persons with disabilities will exceed 99.6 percent.

- At peak travel times, vehicle loads will not exceed 150 percent of the vehicle’s seated capacity.

- In the urban area, DRT aims to have:

- Dwellings within a 500-meter walk of a bus stop: 80 percent, and

- Dwellings within an 800-meter walk of a bus stop: 95 percent.

- In the rural area, 100 percent of dwellings will be served by Demand Response at the curb (such as the entrance to a property).

- Customers who are eligible for Specialized Transit are provided an accessible door-to-accessible-door trip based on their eligibility. Customers with unconditional eligibility will receive trips using only Demand Response service. Customers with conditional eligibility may receive trips that include travel on a combination of Demand Response and scheduled service.

Despite DRT’s well-rounded transit equity approach, its staff identified two areas of opportunity for them to accomplish more. First, the staff hopes to increase the agency’s engagement with priority communities and equity groups and their participation. DRT is launching an ambassador program to work on such engagement. Second, the staff hopes to deploy service enhancements in priority neighborhoods more quickly; however, this requires additional revenue service hours (above and beyond those already planned for growth areas), delay management strategies, and reduction in pressures on other parts of the agency’s service.

Funding and Financing

As a department within the Regional Municipality of Durham, much of the funding for DRT services comes from property taxes, with the rest consisting of funding from fares, gas tax revenue, and reserve funds. In 2022, transit service accounted for 9 percent ($264 million) of the Region’s total budget. In March 2023, the Regional Council approved a 10-year Transit Service and Finance Strategy that includes growth in revenue service of 5–10 percent each year. Service growth is emphasized within regional spending priorities, which specifically helps to address DRT’s transit equity commitments, but transit equity is not identified as a specific line item within approved budgets (DRT 2023a).

Data Collection and Management

DRT staff provided detailed information about the equity-related data the agency collects, including the frequency of data collection and the level of granularity of each data set, as shown in Table 13. DRT staff also outlined the data the transit agency does not currently collect but that are available, as shown in Table 14. DRT employs a dedicated data scientist in the role of Program Manager for Data and Analytics.

When discussing the opportunity to use existing data or performance measures in a new way that could tell a story about their riders, DRT staff suggested a few ideas. Trip data with origins and/or destinations could help data users understand complete customer journeys as well as service

Table 13. DRT data, collection frequency, and granularity by data set.

| Data Type | Collection Frequency | Granularity |

|---|---|---|

| Ridership | Daily |

|

| On-Time Performance | Daily |

|

| Customer Service | Daily |

|

| Service Availability | Daily |

|

| Bus Video Footage | As required |

|

use patterns. Customer complaints or requests can be helpful to understand which needs existing service is not currently meeting or highlight equity or accessibility pain points, such as stops with poor wheelchair access or neighborhoods that feel their service is insufficient for their needs or comparable with adjacent neighborhoods. Demographic data could help identify needs, challenges, and perspectives according to rider subsets (e.g., women of color or people with disabilities who have low incomes).

Lessons Learned and Challenges

DRT staff suggested that accessibility improvements (both in terms of supporting people with disabilities and providing service throughout the Region) help everyone and do not cater only to specific groups. This lesson helps with buy-in for transit investments. Additionally, DRT is structured so that the Change Management Group (responsible for leading much of the equity efforts) and Eligibility Office (responsible for reviewing Specialized Transit applications) report directly to the General Manager, which helps establish equity as a part of the culture instead of simply a box to check or a performance measure to watch. This structure also helps DRT make equity part of everything the agency does, from hiring to the design of bus wraps.

Table 14. DRT data not collected.

| Data Not Collected | Reason Not Collected, per Agency |

|---|---|

| Service Demand |

|

| Customer Demographics (for segmentation) |

|

| Customer Satisfaction (detailed quantitative & qualitative) |

|

One of the challenges DRT has faced recently is the need to continue growing the amount of service the agency operates to meet the needs of the growing region; due to expansion of residential development into new areas, the agency cannot grow fast enough. Because of the transit agency’s specific commitment to provide 24-hour transit service in urban areas and nearly 24-hour service in rural areas, new residential developments require additional routes and/or Demand Response transit services.

Summary

Key Challenges

- Regional Growth. As the Region grows and new residential areas are developed, DRT is challenged by the need to provide additional transit services in new areas to adhere to service standards.

- Large Rural Service Area. A large portion of DRT’s jurisdiction consists of low-density rural areas. Providing effective transit services in these areas is difficult for any transit agency, and DRT is especially challenged by its commitments to lengthy spans of service seven days a week and to ensure riders in rural areas “will not wait more than 60 minutes for a pick up, with an average overall wait time less than 45 minutes” (DRT 2023b).

Notable Practices

- Comprehensive Approach to Transit Equity. Instead of targeting certain aspects of transit service (e.g., on-time performance or affordability) or service in certain areas (e.g., additional service in an area of high need), DRT works to ensure that everyone, throughout the service area, has useful access to transit (e.g., within an easy walk via safe infrastructure, short headways, and late-night service). To best serve priority areas, DRT applies weighting factors to further improve service in these neighborhoods.

- Regionally Identified Priority Neighborhoods. The Region’s public health department led the process to identify priority neighborhoods (defined as areas of the region that require “focus to build on health and well-being”), which have the lowest income levels in the Region, as well as lower adult education levels and higher unemployment rates. Instead of conducting its own analysis on which areas of the Region to focus its equity initiative on, DRT used the existing priority neighborhoods to inform transit equity efforts. This decision leverages work from other departments in the Region while also contributing to a cross-sector solution.

Lessons Learned

- Accessibility Helps Everyone. DRT has learned that transit accessibility—accessibility for people with disabilities and accessibility throughout a region—helps everyone in the community by improving service for all while also reducing public costs associated with unemployment, limited access to healthcare, and social isolation.

MBTA

Since 2009, MBTA has been a division of MassDOT. The transit agency provides service to around 200 cities and towns in the Greater Boston metropolitan area, Eastern Massachusetts, and parts of Rhode Island (MBTA 2023a). The MBTA Board of Directors includes the Secretary of Transportation for MBTA, a member with municipal government experience, and five other members appointed by the Governor of Massachusetts. MBTA is overseen by the MassDOT Board, which has 11 members, all appointed by the Governor, and serves as the governing authority for the agency (MBTA 2023b).

MBTA directly operates service for three heavy rail lines, two light rail lines, the Silver Line bus rapid transit and trolleybus service, and some of its MBTA bus local and express fixed route service.

Table 15. MBTA service summary.

| Operating Statistic | Total |

|---|---|

| Service Area Size (Sq Mi) | 3,244 |

| Service Area Population | 3,109,308 |

| Modes Operated | Bus, BRT, Commuter Rail, Demand Response, Ferry, Heavy Rail, Light Rail, Trolley |

| Annual Unlinked Trips | 120,951,784 |

| Annual Vehicle Revenue Miles | 79,972,611 |

| Annual Vehicles Revenue Hours | 5,887,367 |

| Operating Expenses by Revenue Source | |

| Fares and Directly Generated | $ 220,114,223 |

| Local Funds | $ 177,860,534 |

| State Funds | $ 533,925,193 |

| Federal Funds | $ 933,023,661 |

| TOTAL | $1,864,923,611 |

| Operating Expense per Trip | $12.96 |

Data Source: National Transit Database 2021.

Image Source: TTI.

The transit agency’s remaining MBTA bus service and all services for the MBTA boat (five ferry routes), MBTA Commuter Rail (13 lines), and the RIDE ADA complementary paratransit service are purchased from other providers.

MBTA offers an alternative service available to ADA paratransit customers called the RIDE Flex, in which customers can choose to take a trip through local for-hire ride services in the program in lieu of scheduling a paratransit trip on the RIDE; MBTA subsidizes up to $40 for each trip after the customer pays the first $3 to the trip provider. MBTA also operates around 100 parking lots and garages across its service area (MBTA 2023c).

Table 15 presents a summary of MBTA’s 2021 performance, and Figure 3 is a snapshot of the transit agency’s service area.

MBTA and MassDOT were chosen as a case example because of their collaborative equity analysis work between different departments within a state agency and emphasis on going beyond federal requirements to collect meaningful information related to service equity. The agency developed a rolling rider census update process and uses those data to inform several aspects of service planning across its work. The agency also employs special data collection efforts to better understand the rider experience, targeting hard-to-reach populations as an important emphasis area in data collection and analysis.

Agency Definition of Equity

MBTA and MassDOT do not currently have an adopted definition of equity, even as the larger agency considers equity in many of its efforts. MBTA has a pending equity definition currently under review for inclusion in the transit agency’s strategic planning process. MassDOT recently offered an equity definition for approval as part of its draft long-range plan (which is in the process of being vetted along with the equity definition). This definition aims to be consistent with the environmental justice definition used by the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA). MassDOT’s approach considers how equity is dynamic and not the same thing for all groups of people or from year to year. The agency instead focuses on how its efforts can be seen through an equity lens. MBTA and MassDOT also look to the Boston MPO and their discussion on how the evolution of their equity definition should include both current and historical disparities in equity (i.e., remedying historical inequities through a level of proactiveness).

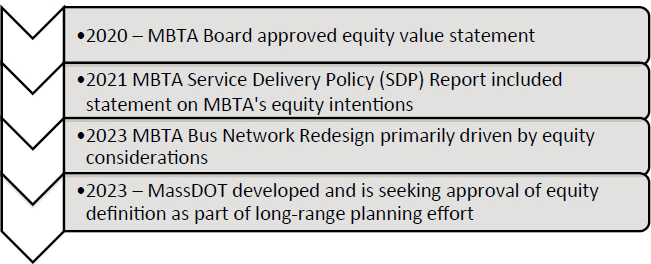

Adoption of Equity Effort

MBTA staff provided a value statement approved by the MBTA Board of Directors in 2020 on equity:

We commit to prioritizing the needs of our transit-dependent riders, our employees, and the economic regions we serve in decision-making processes to eliminate unjust and unintentional disparities.

MBTA’s 2021 Service Delivery Policy (SDP) Report (MBTA Fiscal and Management Control Board 2021) states that with respect to equity:

The MBTA strives to improve access to opportunities and service quality for transit critical populations, including low-income people, people of color, seniors, people with disabilities, and those in low- or no-vehicle households.

MBTA’s Bus Network Redesign (BNRD) Final Report (Better Bus Project 2023), which discusses equity considerations as the primary driver for the project, includes the following definition of equity:

Equity is defined as improving access and quality of service for transit-critical populations: low-income populations, people of color, seniors, people with disabilities, or people who live in households with few or no vehicles.

Institutional Structure and Governance

The creation of MassDOT in 2009 combined several agencies in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts under one umbrella in an effort to combine several aspects of more administrative work. Services shared between MBTA and MassDOT include the Office of Performance Management and Innovation (OPMI), Office of Transportation Planning (OTP), Office of Diversity and

Civil Rights (ODCR), and legal and clinical services. As a result, MBTA and MassDOT have a number of individuals who are engaged in research and performance measurement, working together and sharing resources as needed between the division (MBTA) and the parent agency (MassDOT). Relevant groups for MBTA include its strategic research team and the policy and transit planning team. OPMI and OTP work together on several performance measurement efforts. Different teams within MassDOT divide up their work between MassDOT and MBTA in different ways, but no one employee is fully employed within a single agency.

OPMI (reporting to the MassDOT Chief Administrative Officer) is focused on performance measurement, data, and research; the office has the ability to leverage work across the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (e.g., surveying work on tolling programs, vehicle census information). OTP (reporting to the MassDOT Undersecretary) works with different modal divisions within MassDOT at their request while triangulating with OPMI on data and metrics works; OTP often provides planning resources to other divisions that do not have their own. MassDOT also has a Rail and Transit Division, which collaborates with smaller rail agencies in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Sometimes offices within MassDOT will negotiate who is leading and collaborating on which projects. MassDOT’s State Planning and Research (SPR) funding is allocated through an internal solicitation between all their offices to figure out how the funding will be used.

MassDOT offices are also able to collaborate on requests from places outside of Boston through relationships developed over time between different groups and overlapping focus areas. For small transit operators outside of Boston looking for access to services and tools at MassDOT, most requests are routed through the Rail and Transit Division (which manages and liaises with the regional transit authorities outside of MBTA). An example of a current project is a statewide transit accessibility and service coverage tool to examine travel behavior and access to critical destinations for key demographics.

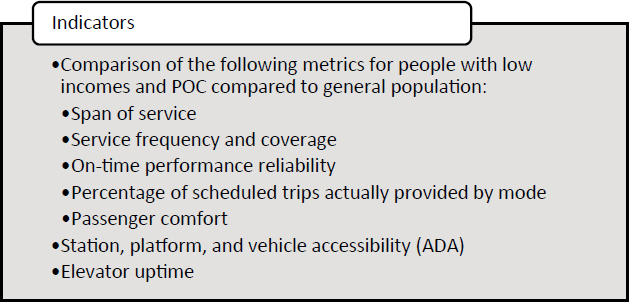

Current and Potential Indicators

MBTA and MassDOT do not have set targets attached to their equity goals. One of the agency’s concerns in target setting is that issues can still be present even if targets are met, making the previously set targets less meaningful in achieving equity. MBTA prefers to perform checks on service equity performance rather than setting targets to track changes over time and obtain an ongoing understanding of the differences in people’s lived experiences.

MBTA staff noted that fare equity can be challenging to calculate because FTA does not allow transit agencies to project out how the service change might change the demographics of ridership, as the analysis must assume that the demographics will remain static. However, in cases when a service change transforms the ridership of the service, the actual equity impacts could be significantly different than the analysis would capture.

MBTA’s latest rider survey information showed that the number of transit riders who self-identify as a minority increased from 34 percent in 2016 to 58 percent in 2022, while the number

of riders from low-income households likewise increased from 29 to 48 percent over the same period (OPMI 2023b).

Target Setting and Recent Performance

MBTA’s SDP, which is prepared by OPMI, is an example of how the transit agency uses some rudimentary measures of targets for service delivery across its system; these measures include measurement of impacts for the number of riders of color or low-income riders. The SDP sets how MBTA evaluates service quality and allocates service to meet riders’ needs, including objectives that define key performance characteristics (including equity), quantifiable standards for meeting those objectives, an outline of the service planning process (along with minimum levels and targets), and process for public involvement (MBTA 2023d). The SDP Report includes equity principles woven into some measures; for example, the description of frequent coverage measurement states that frequent service is prioritized (in addition to other factors) in areas with high proportions of people most likely to rely on transit.

In the SDP analyses, MBTA calculates a scorecard of equity data from the rider census for each metric. Results on the scorecard are intended to represent a snapshot in time for that metric. Figure 4 shows an example from the Fall 2022 SDP of the performance measured for the frequency of service according to effective wait times relative to established standards; the table compares the performances for overall riders, low-income riders, and riders of color (OPMI 2023d). The report tables depict whether the performance for a given measure has improved or worsened compared to the previous report period. The measures included in the report are defined as follows:

- Span of Service – the percentage of riders on routes who were scheduled to meet or surpass their expected hours of operation.

- Frequency of Service – the percentage of riders on routes who were scheduled to meet or surpass their expected frequencies throughout the day.

- Base Coverage – the percentage of the population who lives within a half-mile of any MBTA service in the MBTA service area.

- Frequent Service Coverage – the percentage of the population who lives within a half-mile of frequent MBTA service in areas that either have a high combined population and employment densities or have a moderately high combined population and employment densities along with above-average proportions of low-income and low-vehicle households.

- Station Accessibility – the percentage of ADA-accessible MBTA stations.

- Elevator Uptime – the percentage of total elevator-hours in which elevators are operational.

- Platform Accessibility – the percentage of total platform-hours that are ADA-accessible via elevators.

- Vehicle Accessibility – the percentage of trips the MBTA provides with at least one ADA-compliant vehicle (applicable to the Green Line only).

- Reliability – the percentage of passengers on routes who pass on-time performance tests.

- Service Operated – the percentage of scheduled trips actually provided for each mode of service.

- Passenger Comfort – the percentage of passenger travel time experienced in comfortable conditions.

Engagement and Responsiveness

MBTA uses its rider census information (along with ridership data) to help inform the agency’s outreach programs. For the Massachusetts Household Travel Survey (MHTS) and People & Transportation Project, MBTA has partnered with local organizations to collect information reflecting the lived experiences of using transit through community-based participation research.

The MHTS effort follows recent best practices identified from other states as they launch MPO or statewide surveys. MassDOT looks at how they can provide incentives for non-traditional participants to take part in the survey and ensure that the survey is available in all languages and formats needed by potential participants. For the rider census updates, the survey is made available in 12 languages (OPMI 2023a).

MassDOT hired a polling firm to conduct door-to-door and intercept surveys along with focus groups for the People & Transportation Project, which will include collaborating with community members to perform the moderation and data collection work. Staff stated that no goals are in place for what kind of information results from these efforts as long as it is reflective of people’s experiences. The agency wants to leave the decision-making to its community partners regarding what they feel are important things to capture so that the agency in turn can interpret those findings as important as well.

The BNRD project began with an analysis of location-based services (LBS) data to generate an initial draft high-frequency route network (as well as non–high-frequency routes), which was then refined through a series of design workshops and public feedback (Better Bus Project 2023). LBS data were appended with information showing which trips were taken by individuals belonging to ethnic minority groups or low-income households. Demographic data from the agency’s Title VI policy definitions were also added. Figure 5 shows the process from the project’s final report.

Planning, Programming, and Operations

MBTA has adapted its rider census information to transcend the required update every 5 years and instead evolve into a rolling annual rider census. This change was implemented to have better, more updated information on their riders; this change also helps the transit agency avoid relying

on outdated information when rolling out new services. Work from the rider census shows that some data characteristics (such as demographics of census blocks) are not necessarily reflective of people in the region and their usage of public transportation. The survey results help inform the transit agency’s Title VI equity analyses, capital planning, service planning, fare policy, and public outreach planning (OPMI 2023b).

As the transit agency pursues other survey efforts as well, the rider census helps in ground truthing for drawn conclusions in other analyses. Underlying demographic information helps the agency weight information collected elsewhere; an example is customer satisfaction information weighted based on demographics (OPMI 2023a). MBTA has found weighting to be a better practice to avoid information from more affluent communities or with higher rates of participation drowning out information from communities with a higher transit need. OPMI has worked with capital planning teams in MBTA through rider census data to help provide information on prioritizing needs in capital projects.

The MHTS’s scope for consultants includes a required sampling plan that describes households’ and individuals’ requirements to provide survey responses, emphasizing a focus on hard-to-reach populations and correcting any nonresponse bias. Examples of these biases include limited English proficiency populations, environmental justice, and other equity-focus communities (OTP 2023a).

The People & Transportation project scope discusses OTP’s interest in information about recurring challenges, burdens, and opportunities for people who travel in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The goal of the project is to gather primary source data on people’s interactions with the transportation network to inform topic areas such as trip purpose, cost, mode preferences, barriers to accesses, and burdens from infrastructure and service quality. Consultants are expected to partner with a non-profit community-based organization that advocates “on behalf of the population group” (OTP 2023b).

MBTA is now close to implementing its BNRD project; much of the equity work for the project was done during the initial planning process. MBTA used data to help back up anecdotal evidence about key areas and destinations in need of transit service. The transit agency noted that public response on proposed changes could sometimes conflict with the best possible solution for achieving better service equity; for instance, some of the proposed route changes were ultimately reverted to status quo in the final redesign plan (as opposed to being a clean slate redesign).

The executive summary of equity and Title VI findings from the BNRD states that the project focuses on prioritizing new bus services and resources for low-income riders, riders of color, people without easy access to a vehicle, older adults, and riders with a disability; this includes 50 percent of new bus services going to minority populations and 39 percent going to low-income populations (Antos and Povish 2022). The BNRD analysis used the travel-demand data of these key ridership groups to prioritize additional service investments by weighting the populations more heavily in the analysis inputs.

Funding and Financing

Staff noted that if federal funding is involved in the project, then the agency is bound to the requirements on measuring equity performance. However, if federal funding is not involved, then MassDOT has some flexibility on procurement within the allowance of the Commonwealth rules. For example, the Commonwealth added LGBTQIA+ and disability categories to its standard diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) requirements. While the agency’s focus on equity is on rider experience, improved equity with respect to personnel and procurement is also helpful toward these efforts. MassDOT’s SPR funding is allocated through an internal solicitation between all its divisions to figure out how the funding will be used.

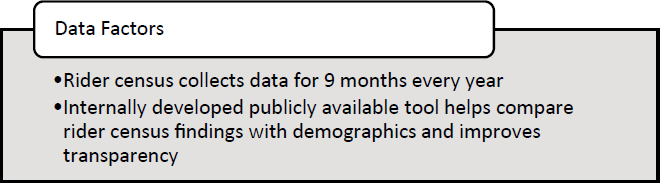

Data Collection and Management

MBTA uses the rider census effort to capture ridership as it stands for most of the year during periods of regular service. For the rolling rider census updates, MBTA collects data in the field for approximately 9 months (typically March through November) to avoid the winter weather season when riders are less willing to participate (OPMI 2023b). The break-in data collection also helps the transit agency have built-in time to release the new data set and start back up the next year.

OPMI developed an online tool (named the MBTA System-Wide Passenger Survey Interactive Web Tool) that displays information from the rider census according to given categories. The tool includes passenger survey information for different fixed-route service modes and information from several measures (including race, ability to understand English, fare product, gender, ethnicity, household income, Title VI categories, and usable cars) (OPMI 2023c). The tool is available to the public, and data can be downloaded as desired; OPMI determined that the online tool would help increase transparency and reduce the time it takes to respond to public data requests.

Lessons Learned and Challenges

While minimum federal requirements can be very prescriptive and limiting, MBTA staff noted that it is beneficial to have federal requirements in place to force agencies to do something that otherwise would not happen. MBTA has found that some requirements help engage staff across the agency in equity conversations.

MBTA staff noted that equity work in projects like the SDP uses federal types of categories even if the analysis is not federally required. The agency has discussed terms used in these categories and whether the given terms are nuanced enough in the framing of language.

Summary

MBTA and MassDOT monitor performance indicators related to equity over time as an approach rather than using a target-setting approach to determine whether equity goals have been achieved. The agency’s data collection efforts and projects emphasize equity as the primary driver of its effort to learn more about barriers to transportation service and the lived experiences of riders. Agency staff collaborate together on several data analyses and planning efforts as a result of MassDOT’s structure in sharing staffing roles between the larger agency and divisions within the agency.

Key Challenges

- Implementing Findings. The results from the data analyses and planning projects that indicate the best potential solution to improve the equity of service can sometimes run into barriers to implementation due to public response to concern about service changes.

- Equity Definitions. MassDOT and MBTA do not have a single driving definition of equity that is used across agency efforts because the number of groups within the larger agency. Another similar challenge can be moving beyond federal definitions of equity categories that may not service local purposes most effectively.

Notable Practices

- Data Recency. MBTA increased its rider census efforts from the required 5-year period, transforming the data collection to a rolling annual effort that provides more recent and relevant

- Tool Development. The Service Delivery Policy reports, and the interactive web-tool produced by MBTA, provide transparent information and resources to the public on regularly updated equity-related data.

information on riders; this process helps ensure the data are useful for various planning efforts and applications from MBTA and MassDOT.

Lessons Learned

- Internal Collaboration. Staff within MassDOT work collaboratively on various projects affecting MBTA or other transit providers in the state based on expertise and capacity; the agency developed this approach over time to navigate the complexity of resources and overlapping efforts across divisions.

- Monitoring Indicators. Due to past experiences at the agency, staff are hesitant to set targets to avoid a perception of “achieving” equity; conversely, the agency monitors performance indicators (through a scorecard approach) to understand the extent to which MBTA is achieving service goals.

Metro Transit

![]()

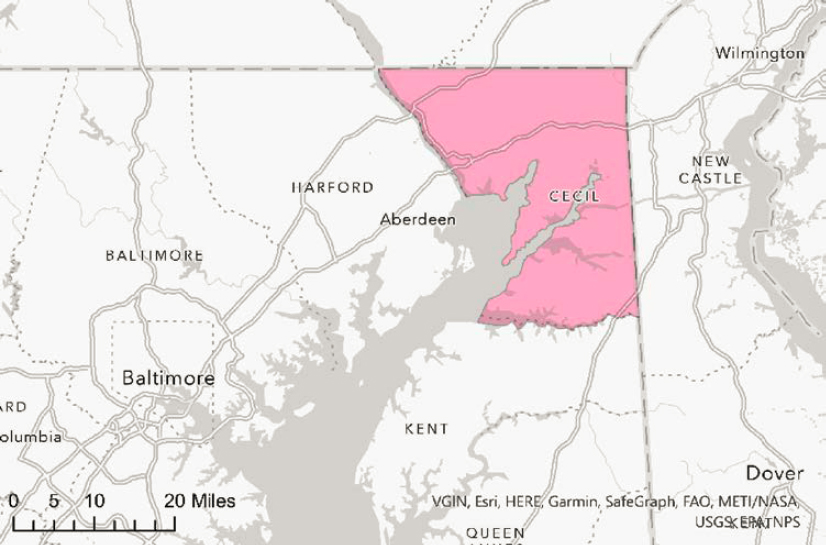

Metro Transit has been a division of the Metropolitan Council in the Minneapolis-Saint Paul region of Minnesota since 1994 (Metropolitan Council is the MPO for the region). In addition to fare revenues and federal grant funding, this transit division receives state motor vehicle sales tax and state general fund revenues. Metro Transit provides local fixed-route bus (47 routes), express route bus (71 routes), bus rapid transit (five lines), light rail (two lines), and commuter rail (one line) service to the region (Metro Transit 2022b); the division also recently started a microtransit pilot program in September 2022 called “micro” for a zoned area in Hennepin County (Metro Transit 2023d). Metropolitan Council provides ADA paratransit service (Metro Mobility, n.d.).

Table 16 presents a summary of Metro Transit’s 2021 performance, and Figure 6 is a snapshot of the transit agency’s service area.

Metro Transit was chosen as a case example because of the transit agency’s multiple years of experience with equity measures and dedicated team of data scientists who were available to work

Table 16. Metro Transit service summary.

| Operating Statistic | Total |

|---|---|

| Service Area Size (Sq Mi) | 492 |

| Service Area Population | 1,731,667 |

| Modes Operated | Bus Commuter Rail Light Rail |

| Annual Unlinked Trips | 32,861,129 |

| Annual Vehicle Revenue Miles | 24,598,887 |

| Annual Vehicles Revenue Hours | 2,100,770 |

| Operating Expenses by Revenue Source | |

| Fares and Directly Generated | $34,879,635 |

| Local Funds | $31,315,867 |

| State Funds | $ 311,787,935 |

| Federal Funds | $34,841,540 |

| TOTAL | $412,824,977 |

| Operating Expense per Trip | $12.49 |

Data Source: National Transit Database 2021.

Image Source: TTI.

on the development of the associated methodology. The transit agency’s equity performance measure process and methods were heavily influenced by responses to specific feedback from the public regarding the quality of bus stops and other amenities and formal data requests from the American Civil Liberties Union to disaggregate fare enforcement data by race, offering an example of an approach that external stakeholders have scrutinized since its inception.

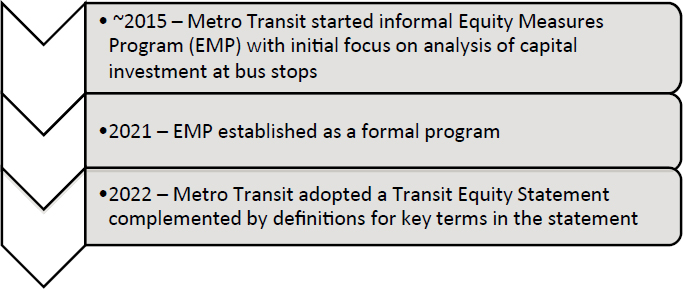

Agency Definition of Equity

Metro Transit’s approach to equity was also significantly influenced by public input that highlighted inequity in service provision. Similarly pushed by external pressure, Metro Transit pioneered service equity analysis techniques in the context of the Title VI program. The agency was also early among transit agencies to recognize that avoiding disparate impacts was not enough to drive equity in service design and delivery. As such, the transit agency’s way of explaining its approach to equity highlights specific communities and explains how it will address their needs. Instead of a definition of transit equity, Metro Transit adopted a Transit Equity Statement in 2022 (https://www.metrotransit.org/TransitEquity) (the following statement is specific to Metro Transit and does not apply to the Metropolitan Council (of which Metro Transit is a division, as described in the following section):

Metro Transit acknowledges that providing safe, affordable, and reliable transportation increases opportunity. Transit services and programs should be built to equitably benefit all, especially under-served communities, including BIPOC, low-wealth, women, people with disabilities, LGBTQ+, youth, and older adults. Transit equity requires identifying and addressing injustices and building actionable pathways to create a fair and more just future.

Metro Transit understands that transit decisions can impact the ability of under-served communities to find and keep jobs, reach medical care, access educational opportunities and affordable housing, and develop and maintain social

connections, among other impacts. Transit services and investments can reduce spatial inequalities that contribute to racial, environmental, and economic disparities.

Metro Transit has an essential role and responsibility to examine all decisions impacting our region’s access to quality transit, reduce existing disparities, and prevent further inequities by:

- Reviewing and revising policies,

- Seeking partnerships with other responsible institutions, and

- Improving planning and operational practices.

To support this statement, Metro Transit also provides “Key Definitions” on its website so that people reading the statement understand what it refers to [these definitions are specific to Metro Transit and do not apply to the Metropolitan Council (of which Metro Transit is a division, as described in the following section)]. These definitions are as follows:

Under-served communities: Local communities that have been historically excluded from transit decision-making and benefits while carrying disproportionate burdens.*

BIPOC: Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color.

Disability: Includes people with physical, sensory, emotional, and cognitive disabilities, and those with chronic/severe illness. We understand the experience of disability to occur within any and all walks of life, with deeply felt connections to all communities impacted (adapted from Sins Invalid Organization’s mission).

Inequities: When a group or an area is serviced, represented, and/or invested greater than another group or area based on access, power, and/or privilege.

Spatial inequalities: The unequal amount of resources and services that can be accessed depending on the area or geographical location.

*MnDOT: Advancing Transportation Equity Initiative focuses on communities: (1) Underrepresented in transportation processes; (2) Experiencing known inequities in access or outcomes; (3) With unique transportation needs not well served by a business-as-usual approach.

Institutional Structure and Governance

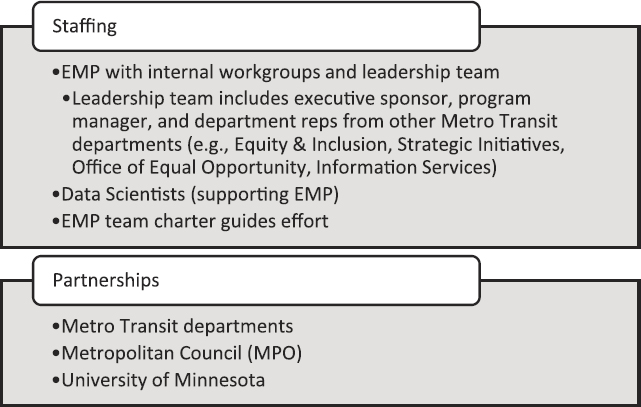

Metro Transit is the largest division of the Metropolitan Council, with multiple programs or groups touching on performance measurement and service equity. Metro Transit started the Equity Metrics Program (EMP) informally about 8 years ago. An early project focused on an analysis of capital investments at bus stops. The product of that analysis, the Better Bus Stops program, resulted in changes in public engagement practices, priorities in how the division assigns available resources, and new commitments to performance measurement that measure metrics across specific groups (e.g., race, income, or neighborhood). The EMP was established as a formal program in fall 2021 to continue the division’s commitment to transit equity (Metro Transit 2021).

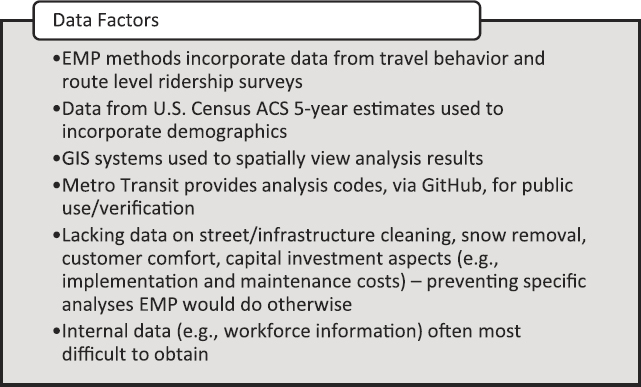

The EMP consists of a leadership team and a set of internal workgroups involved in equity metrics work. The leadership team includes an executive sponsor, program manager, and key departmental representatives from other departments in Metro Transit (e.g., Equity & Inclusion, Strategic Initiatives, Office of Equal Opportunity, Information Services) as well as room for external partner representatives. The leadership team reviews and guides equity metrics and their targets and guides conversations with other stakeholders about the metrics (Metropolitan Council 2021b). The EMP’s data scientists work on developing a methodology around equity metrics; this methodology includes measurements with disaggregation by race using American Community Survey (ACS) data.

The Better Bus Stops program was an outgrowth of the Engineering and Facilities group, and Strategic Initiatives also continues to work in service equity analysis. Metro Transit’s Equity and Inclusion Team and EMP look at metrics from various programs (e.g., Better Bus Stops) and program evaluations on an ongoing basis to identify metrics that help the division understand the equity impacts of service and investment planning. The team has a charter that outlines their purview and has been developing goals and associated metrics in assessing equity in Metro Transit employment.

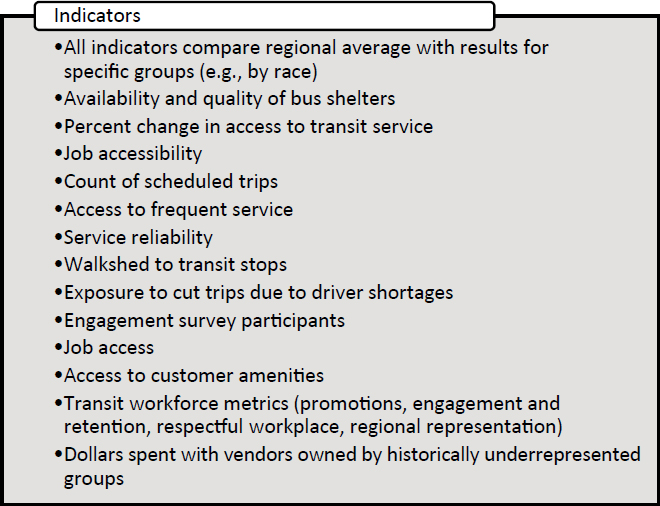

Current and Potential Indicators

As previously noted, an early application of Metro Transit’s equity methodology was developed with regard to measuring the infrastructure at bus stops, aiming to measure the quality of the bus stop experience for riders. The division found that the demographic data from onboard surveys were not sufficient on their own as a tool to measure service equity across the network. Therefore, the methodology incorporates ACS data and is designed to be applied to any performance indicator that can be measured at the transit stop level. Examples include on-time performance, headway reliability, frequency, and span of service.

The Better Bus Stops capital project initially began in 2014 with the goal to add shelters at 150 bus stops and improve 75 additional bus stops with better shelters and pedestrian access (Metro Transit 2017). As of 2021, data from the program show that people of color (Metro Transit uses the term BIPOC) have access to shelters, light, and heat (temperatures in the service area can be below zero) at bus stops at rates similar or higher than the Metro Transit system average (see Figures 7 and 8) (Martina, Dungca, and Farrington 2023) (Farrington, Fisher, and Broughton 2022).

Metro Transit’s methodology looks at walkshed distances around bus stops to measure and then aggregate demographics of potential riders across multiple stops of the bus route. The first step is generating walksheds around the stops at 5-, 8-, 10-, and 12-minute intervals (walk time). Then, staff determine the proportion of the census block group in the walkshed to determine the demographics of potential riders according to ACS data. The population of each race in the block group is scaled by the area of the block group within the walkshed; this gives the team an estimated population of who has access to the service at the given bus stop (Metro Transit 2022a).

Figure 9 presents an example of the methodology’s proportional estimation of population groups with a transit stop walkshed based on area-weighted interpolation. Figure 9 also shows three Census block groups (noted by the numbers 1, 2, and 3). The Metro Transit logo in the middle notes the location of the bus stop, and the blue polygon area around the logo is a measurement of the walkshed. In Block Group 1, 50 percent of the area is covered by the walkshed, while the other 50 percent is not. This 50 percent coverage is multiplied by the 100 residents of color estimated within Block Group 1, resulting in a weighted estimate of 50 such residents within the walkshed (Martina and Dungca 2022). Metro Transit also averages access for stops with overlapping walksheds and then aggregates them at the route level so that resident access levels are not counted multiple times in the process (Reid 2020).

Metro Transit looks at key performance indicators (KPIs) for equity metrics on an annual or quarterly basis; these metrics include measures in the areas of service, customer amenities, workforce, purchases, and engagement (Martina, Dungca, and Farrington 2023). The same KPIs are published as part of the division’s Annual Service Equity Evaluation Report. The July 2023 presentation on these KPIs showed that more Metro Transit trips are being provided to residents who identify as Black or Native American (compared to the regional average); a larger percent of residents who identify as Black, Native American, or Hispanic have access to high-frequency service; and more jobs are accessible by transit to residents who identify as Black, Native American, Asian, or Hispanic. Conversely, during fall 2021, Black and Native American residents were more likely to live near stops with cut trips due to transit workforce shortages (Martina, Dungca, and Farrington 2023).

Metro Transit produces annual Equity Metric Reports to track the progress of system accessibility (to destinations such as jobs), access to frequent service, passenger time spent in buses with standees, service availability, and on-time performance. The annual reports vary over time due to the areas of interest for that particular year.

- The Accessibility Equity Report found that according to the 2020 schedule (using GTFS data), job accessibility was higher for residents of color compared to White residents because of the concentrations of jobs and populations near downtown. The report also found that similar accessibility patterns across service types and days of the week (Reid and Dungca 2021).

- The Access to Frequent Service Equity Report found that according to 2018 ACS data, 27 percent of residents of color could walk to high-frequency transit compared to 16 percent of White residents due partially to the concentration of frequent service lines in downtown areas. The report notes that the metric only measures access rather than actual ridership (McKnight, Reid, and Dungca 2021).

- The Passenger Time Spent in Buses with Standees Equity Report found that by comparing the differences between fall 2019 and 2020, routes serving a higher proportion of riders of color had more time during service when people were required to stand due to high ridership compared to routes serving predominately White riders; this analysis used automatic passenger counter (APC) data to determine bus loads and standee times (Ditmer and Dungca 2021b). Showing the flexibility of this type of metric, the transit industry applied similar analyses to assess which vehicles exceeded COVID-19-related capacity levels and showed that people of color experienced a disproportionate risk of their vehicles being over the “safe” limit for riders.

- The Service Availability (Trip Count) Equity Report found that Black and Native American residents have higher average access to weekday trips (both above 60 trips) compared to White residents (51 trips) (Whited and Dungca 2021).

- The On Time Performance Equity Report found no evidence of disparities according to race in OTP based on walksheds to transit stops and timepoints data (Ditmer and Dungca 2021a).

The EMP team has also completed one-off studies for other projects at Metro Transit as needed. One example is an analysis for the Orange Line bus rapid transit service; the team worked with service planners to run service scenarios and an access to opportunity analysis on how well riders could reach key destinations (e.g., education, jobs) in 30 minutes by transit. The results were disaggregated by race and led to changes in the service plans. The team has found that service planners in the division want to continue to use these kinds of perspectives for other planning projects. This kind of work does require some customization in the analysis and multiple months of lead time to accomplish.

Target Setting and Recent Performance

Metro Transit finds target setting important in measuring performance because targets help the division define success so stakeholders can see both the performance and the agency’s definition of equitable service in practice. The EMP aims to apply a consistent and transparent methodology for

performance measurement efforts across the agency by disaggregating metrics by race and setting targets and goals for performance to improve agency accountability (Metro Transit 2021). Although the division has struggled to develop meaningful targets across all services, it is committed to equity in infrastructure at bus stops (including implementing bus shelters, heat, and lighting at all stops). Metro Transit uses the same analysis methodology for bus stop improvements to ensure the division is not contributing to any greater service disparities with service planning efforts.

The EMP has also created an Equity Metric Template, which is used to set up standards for equity performance measurement; the template can also be used by different groups in Metro Transit to help determine how to measure equity for their specific functional area using a consistent methodology. The EMP team has found that centralizing the methodology within their group as they work with others in the division has been important in developing metrics in a timely and repeatable manner. The template includes the following sections (Dungca 2023):

- Reason for Review, Goal, and Metric

- Evidence of metric importance and relevance to advance racial equity

- Goal(s)

- Alternative goal(s)

- Proposed metric linking to the goal(s)

- Proposed Accountability Process

- Internal accountability

- External accountability

- Data Sources

- Proposed Approach for Disaggregation by Race

- Metrics and Results

- Conclusions

- Next Steps to Determine Whether Goal or Metric Is Included in Racial Equity Lens

Metro Transit also conducts required Title VI analyses on service changes and potential impacts to low-income communities. The division also has an internal policy on the tolerance level allowable in terms of service impacts and compliance targets that staff seek to achieve. Metro Transit usually uses external consultants to conduct Title VI service equity analyses but will sometimes add the findings to other metrics the EMP is working on.

Metro Transit’s 2021 Annual Service Equity Evaluation Report discusses the division’s framework for evaluating impacts of service changes. The division looks to quantify how much fixed route service is within a reasonable walk distance from a person’s home and how service availability has changed over time (through the number of trips at the stop). The framework uses the percent change in service for different population groups and then weights the percent change in weekly scheduled trips taken by those groups; this helps the division look at stops with greater impact of service based on the number and types of population living within the stop walkshed (Metro Transit 2022a).

The 2021 report focuses on service changes that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic; Figure 10 shows that the measurement of service decreased for different population groups compared to before the pandemic. Although Metro Transit does not have benchmarks, the tolerance levels in the service equity analyses are sometimes used in this fashion. Last year, the division changed the allowable tolerance level from 20 percent (used in the 2021 report) to 15 percent as a result of public feedback. The report states that Metro Transit’s improvement projects for better speed and reliability of transit service are prioritized (along with other evaluation factors) to target areas with high percentages of people of color, people with low incomes, and residents who rent their homes and areas with larger numbers of low-wage jobs (Metro Transit 2022a).

The 2021 report also includes the several service metrics disaggregated by race to help identify areas where some residents may experience a higher quality of service compared to others

(particularly White residents compared to other racial or ethnic groups) (Metro Transit 2022a). The measurements for each population group are compared to each other and to the regional average. Figure 11 shows the results for access to frequent service during 2021 (i.e., routes that serve stops at least four times per hour). The division added metrics to its 2021 analysis, which looked at the impacts of cut service as a result of workforce shortages during the pandemic (indicated by asterisks in the bulleted list at the end of this section); EMP staff found these measures led to productive conversations with others in Metro Transit working on the scheduling and management of resources. These measures also helped the agency address changes in service delivery during the emergency, including highlighting routes that serve a high number of people of color that were

not receiving enough capacity in terms of vehicle numbers to help maintain social distancing during 2020 (Ditmer 2021). The following service metrics are included in the report:

- Accessibility to jobs (i.e., service utility)

- Count of scheduled trips (i.e., service availability)

- Access to frequent service (i.e., service utility)

- On-time performance (i.e., service reliability)

- Cut trips and percent of service delivered* (i.e., service reliability)

- Passenger crowded*

The Metropolitan Council published a report on equity considerations, which included measurement of Areas of Concentrated Poverty (ACP) where the majority of residents are people of color (i.e., ACP50s) (Metropolitan Council 2021c). The community has not responded positively to these measurements, as some felt that these areas showed unclear connections between income and race. As a result, the division has tried to make more distinctions between race and household income in performance measurement. Metro Transit does consider areas of concentrated wealth as a measure in the EMP’s methodology but is somewhat challenged in measuring this characteristic due to limitations from ACS data.

Engagement and Responsiveness

The equity-oriented performance measures Metro Transit tracks are presented to the Metropolitan Council in public meetings where transit riders and other citizens can learn about how the transit agency performs and voice their opinions, often following Title VI-specific discussions or reports. While public engagement regarding the measures is limited, the team that works on the measures actively promotes the use of the measures and/or the skills among the staff by working with other departments to assist with analyses and help their colleagues apply an “equity lens” to the concepts they are developing (e.g., the development of service scenarios with planners to check the resulting impact on transit users’ access to opportunities).

Planning, Programming, and Operations

Some of the measures have influenced specific changes that benefit transit riders. For example, after determining that the quality and/or availability of customer amenities correlated with socioeconomic indicators (e.g., areas with lower incomes and/or higher percentages of people of color had lower quality/reduced presence of customer amenities), the process for determining placement and the type of customer amenities changed. However, the measures do not typically influence decision making because they are not built into the transit agency’s standard operating procedures. Therefore, while the measures can help assess ideas and scenarios (as well as monitor the service performance already available), that type of assessment is not required, nor is it currently conducted during all planning and programming activities.

Funding and Financing

As a division of the Metropolitan Council, about a third of Metro Transit’s operating budget is supported by fare and advertising revenues; the remainder is supported by a combination of regional, state, federal, county, and other revenue sources (Metro Transit 2023b). Metropolitan Council’s annual budgets do include line items for bus stop facility and equity enhancements (Metropolitan Council 2021a); there are no specified line items for the EMP team (or other groups) within Metro Transit because budgeting for those groups is presumably handled separately within the division.

Budget for data scientist-level positions (a role that made the EMP technically feasible for the agency) was first pursued by Metro Transit’s Director of Strategic Initiatives when that director-level

position was formed (around 2014); the director wanted to create a more data-driven group to work on analyses for the transit division. Metro Transit also reclassified the position level from researcher to analyst, which was novel at a time when data analysts were uncommon within public transit agencies; now titles are classified consistently within the data science field.

Data Collection and Management