Summary

The municipal solid waste (MSW) management system in the United States is a complex and distributed system that has evolved over time in response to policies, materials managed, infrastructure and technology, and actors at local, regional, state, national, and international levels. MSW is generally defined as the non-hazardous solid waste generated by the residents, commercial businesses, and institutions of a community. It excludes industrial and construction waste. In 2018, the United States generated approximately 292 million tons of MSW annually, most of which (about 68 percent) were not recycled or composted.1 Other studies have found that as much as 79 percent of recyclable material in the MSW stream is not actually recycled, because of factors such as the material not being targeted for recycling, not being economically viable to recycle, limited access to recycling programs, and low participation rates.

Figure S-1 depicts a generalized process for a MSW management system with consideration of the actors and materials involved. This includes subsystems for (1) production and manufacturing, (2) waste generation, (3) waste collection, and (4) sorting and processing. The collection, processing, and marketing of recyclables are interdependent components, and each must be considered when designing and operating a recycling system since they affect one another. For example, changes in collection methods and materials collected will impact the design and operation of the materials recovery facility (MRF); how the MRF is designed and operated will determine whether materials will be produced that meet market specifications; and changes in market requirements may lead to changes in how materials are collected and processed.

In support of improving recycling outcomes, this study, authorized by the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2022, reviews available information on programmatic and economic costs of MSW recycling programs in municipal, county, state, and tribal governments and provides advice on potential policy options for effective implementation. The focus of this work was on publicly accessible data on the policies and systems in place that relate to the collection, sorting, processing, transport, and sale of recyclable materials, especially those that are traditionally processed in MRFs. Additionally, the report presents several case studies to illustrate how local conditions impact the design, cost, and effectiveness of MSW recycling programs and provide context to inform policy.

Benefits and Challenges of Recycling Programs and the Role of Policy

Recycling involves choices by households, businesses, and many levels of government. The costs associated with managing MSW recycling may require public policy at local, state, and national levels to address financing of these systems effectively. While some recycling programs can be sustained through local policy and resources, others face difficulties such as high infrastructure costs and fluctuating commodity values for recyclables. Smaller municipalities, especially in rural areas, may struggle to achieve economies of scale, making recycling programs financially unsustainable without external support. Markets alone do not provide the necessary incentives for households, businesses, or local governments to engage in effective recycling practices. Heterogeneity—including a broad range of differences across costs, benefits, existing capabilities, material volumes, transportation distances, access to end markets, and cultural norms across regions—is a significant factor in recycling programs, complicating the policy needs.

___________________

1 This Summary does not include references. Citations for the information presented herein are provided in the main text.

NOTES: Other non-residual organic products (e.g., animal feed, energy) may result from treatment of organics but are not discussed in this report. MRF = materials recovery facilities.

Despite these challenges, well-designed and supported MSW recycling programs hold many benefits. These programs can lead to measurable economic gains and the circular economies they enable create jobs, promote business development, and provide further positive social impacts for communities across

the country. In addition to economic gains, associated environmental benefits include reducing use of nonrenewable virgin materials, reducing use and extending the service life of landfills, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Local, state, or federal government intervention through public policy can significantly improve the efficiency, affordability, and accessibility of recycling initiatives. Tailored national policies that address regional and local constraints and provide targeted support can enhance the effectiveness and sustainability of recycling programs across the United States. After consideration of available information on MSW recycling programs, the committee determined that it is helpful to identify and articulate the objective(s) that effective recycling policy is designed to achieve.

Conclusion 3-32: Effective recycling policy targets some or all of the following objectives:

- Enhance end markets for recyclable materials

- Provide stable financing of recycling systems

- Clarify information for consumers, including what is recyclable, how to recycle, and which products best support recycling goals

- Track and evaluate recycling activities through improved data collection and distribution

- Increase the cost-competitiveness of recycled materials (relative to virgin material inputs) and of recycling (relative to landfilling)

- Improve access to recycling collection and processing

- Increase the cost effectiveness of recycling collection and processing

- Decrease contamination of postconsumer recycling streams

- Enhance social and environmental benefits associated with recycling

- Maintain affordability, without undue burdens on low-income households

Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Policies and Programs

Recycling goals may be used to identify benchmarks, measure progress, evaluate success, and simplify the communication of a policy or program’s purpose to important stakeholders (e.g., constituents and citizens of a community, businesses, company shareholders). The most widely used metric for evaluating recycling progress remains the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s 2020 “MSW recycling rate,” calculated as the total weight of recycled MSW divided by the total weight of generated MSW. The popularity of this metric stems from its simplicity and applicability across states and regions, making it accessible to a range of stakeholders. In general, however, weight-based recycling rates and material-specific rates are incomplete metrics for recycling efficiency because they do not adequately account for changes in packaging material composition, waste reduction efforts, and all costs and benefits of using and reusing materials over their life cycle (e.g., economic, social, environmental costs and benefits). Compared with using only weight-based metrics, a sustainable materials management approach, which includes consideration of weight-based recycling, provides a more complete picture of the costs and benefits of using and reusing materials across their life cycles.

Recommendation 2-1: Goals for recycling policy should expand beyond weight-based recycling rates to include informative metrics for sustainable materials management. To support these efforts, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency should study how to combine multifaceted sustainability goals into an overall policy framework, provide guidance for state and local governments to set and measure progress toward those goals, and use this information to evaluate progress. National recycling goals should be material specific but flexible to account for heterogeneity across regions and municipalities. These goals should include environmental, social, and economic targets, including cost-effectiveness. Goal-setting should be

___________________

2 The conclusions, recommendations, and policy options in this Summary are numbered according to the chapter of the main text in which they appear.

leveraged to design a policy framework and set new national recycling goals using best practices such as life cycle assessment and SMART (specific, measurable, accessible, relevant, and time-bound) metrics.

Recommendation 2-2: The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) should enhance data collection and reporting efforts related to municipal solid waste (MSW) and MSW recycling programs to fill significant data gaps, to ensure sufficient and contemporary data are available to inform policy decisions, and to aid in developing and evaluating recycling goals based on sustainable materials management. These efforts should include appropriate input from stakeholders including other federal partners; state, local, and tribal governments; and industry partners. Additionally, EPA’s efforts should include:

- Updating its publicly available website on at least a biennial basis with national-level facts and figures about materials, waste, and recycling. Where possible, this information should expand from input-output modeling figures to include direct observational data. Where necessary, EPA should continue to provide sufficient funding for collecting and reporting these data.

- Developing standard definitions of recycling and methodologies on data collection and reporting for recycling and MSW generation. These definitions and collection methodologies should distinguish between pre- and postconsumer recycling and differentiate between open- and closed-loop recycling. This public information should include, at a minimum, material-specific data on MSW generation, recycling, composting and other food and yard waste management, combustion with energy recovery, and landfilling. To the extent possible, these data should also be reported at regional, state, and local levels.

A summarized list of data needs and their uses are provided in Table S-1. This list is not exhaustive but is representative of the need to improve data availability for decision making.

Key Policy Option 2-1: The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) could support studies to update or otherwise fill missing data gaps to ensure sufficient data are available to inform policy decisions on recycling. These include:

- Tracking household time spent by single and multifamily households on recycling to support more complete and accurate estimates of the economic and social costs of recycling and ensure that life cycle assessment models are as current and accurate as possible.

- Regularly collecting and reporting direct observations of household and commercial behavior related to recycling. In addition to filling knowledge gaps, these data would complement top-down modeling in the recycling system and enable empirical study of the impact of public policy. As part of these efforts, EPA could consider a periodic household and commercial survey for waste and recycling akin to the Energy Information Administration’s Residential Energy Consumption Survey.

Financing of Recycling Programs

Financing of the recycling system in the United States comes from both private and public sources. Typically, local governments, households, and commercial establishments pay for recycling collection and processing with limited funding from state or federal sources. Some local governments use a “general fund” approach in which recycling does not have a dedicated revenue source and is funded along with other categories of expenditure. Other municipalities rely on an “enterprise fund” approach by collecting fees for recycling (or for recycling and garbage collection together), sometimes as an item on property tax bills or utility bills, or as an explicit charge for businesses. By contrast, businesses typically hire and directly pay

for private waste management companies to provide their recycling services rather than relying on government systems. This traditional financial approach includes four considerations: incentives for recycling, cost control, risk management, and distribution of financial burdens.

TABLE S-1 Summarized List of Data Needs and Their Uses for Recycling Approaches

| Domain | Data/Units (where applicable) | Purpose and Use of Data | Primary Actors to Collect and Report Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product characteristics |

|

Ensure that related policies (e.g., EPR/PRO, interventions, product bans) are working, support recyclable labeling, project future material flows | EPA, manufacturers, U.S. Census Bureau, Federal Reserve Board, Bureau of Labor Statistics |

| Waste generation and composition |

|

Help advance the understanding of how the recycling system is performing, estimate level of contamination in recycling streams, complete LCA and LCI, evaluate recycling goals | EPA, states, local governments |

| MSW recycling systems |

|

Evaluate the availability of programs, recycling capacity, level of consumer access and participation, and fiscal stability | States, municipalities, local MRF owners |

| System costs |

|

Estimate consumer cost of recycling more completely and accurately | Local government, compiled by each state |

| State policies and rules |

|

Identify the objectives, economic impact, and constraints of government policy | EPA, state, nongovernmental organization, and industry experts on policy and regulation |

| Technological innovation | Descriptions and inventories of new MRF technologies, sorting technologies for consumers, and new patents | Understand how recycling performance could improve in the future | MSW research and development experts from industry |

| Environmental impacts and improvements | Input data for LCA and LCI; greenhouse gas emissions and air, water, land pollutants from waste and recycled material transport and processing; exposures and health impact estimates (environmental, economic, and social metric units) | Ensure LCA and LCI are updated and accurate | EPA |

| Domain | Data/Units (where applicable) | Purpose and Use of Data | Primary Actors to Collect and Report Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inventory of recyclable and recycled materials | Performance metrics, including fraction recycled (tons/day) and other impact-based indices | Improve markets and enable potential buyers and sellers of materials to be matched more easily | Local governments, MRF owners and operators, states |

| Consumer knowledge and behavior |

|

Provide regular direct observations of household and commercial behavior; improve the ability to evaluate the empirical impacts of public policies; measure social impacts of recycling, including health, distribution of programs; evaluate true cost and benefits of recycling | EPA - Surveys and bin audits measuring behavior and contamination; local governments |

| Macroeconomic impacts |

|

Survey recyclers to enable estimates of material flowrates, enabling estimations of material availability; evaluate recycling impacts on economy | States, manufacturers |

NOTE: EPA = U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; EPR = extended producer responsibility; NAICS = North American Industry Classification System; LCA = life cycle assessment; LCI = life cycle inventory; MRF = materials recovery facility; MSW = municipal solid waste; PRO = producer responsibility organization.

An emerging financing model, extended producer responsibility (EPR), alleviates financial burden on local governments by shifting residential recycling costs to producers who pay for their share of recycling collection and processing costs. These EPR financing rules differ from the original concept of EPR, which is most directly embodied in an “individual”—or “take-back”—policy, in which manufacturers are required to reclaim their own product packaging and eventually the product itself once it has reached the end of its useful life. Fullerton and Wu’s (1998) economic model captures these incentives by demonstrating how market equilibrium—achieved when firms’ production choices align with consumers’ purchasing and disposal decisions—can drive optimal product design, output, and packaging choices, accounting for external disposal costs. Existing “collective” EPR laws provide financing but do not capture all these individual incentives. They also vary greatly by state, and the economic impact of EPR also varies depending on the scope of the law.

If properly designed, these systems may provide incentives for producers to reduce packaging volumes and increase recyclability of packaging and products.

Recommendation 4-1: The United States should increase reliance on extended producer responsibility (EPR), which should cover packaging and expand to other materials as appropriate. EPR policies should include eco-modulation to create economic incentives for manufacturers to design for recyclability, and funding streams for recycling systems and infrastructure. State governments should enact EPR policies to account for regional heterogeneity but should be supported and informed by a national framework with guidelines.

Key Policy Option 4-1: The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), with appropriate funding and authority from Congress, could develop and facilitate a national extended producer responsibility (EPR) framework, as outlined in its 2024 report National Strategy to Prevent Plastic Pollution. If it pursues this framework, EPA should consult with state, local, and tribal governments; nongovernmental organizations; industry; and other relevant partners. This framework should provide guidelines on key elements of state-level EPR policies and recommend minimum state-level standards and best practices. A national framework should provide as much consistency across states as possible and support multistate efforts, while allowing for state-level variation in targets, fees, covered materials, and methods to reflect heterogeneity in costs and benefits across states.

Key Policy Option 4-2: State governments could enact extended producer responsibility (EPR) policies, informed by any minimum standards provided by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. State-level needs assessments should identify gaps in current services and programs and serve as a basis for setting EPR fees. Within an EPR framework, state governments could consider policies, such as recycled content standards, to enhance end markets for recyclable materials.

One of the primary objectives of MSW management programs is to make it easy and convenient for residents to recycle. Achieving this objective is a key reason why curbside collection services are provided on a regular basis to single-family residences. While this type of service can be provided more cost-efficiently to residents in urban and suburban communities, curbside collection may be cost-prohibitive for many tribal and rural communities because of their low population density and long distances between households. Alternative funding mechanisms for rural recycling areas include dedicated financing generated from statewide federal grants such as the Solid Waste Infrastructure for Recycling programs, state-level EPR policies that promote recycling programs in rural areas, and landfill tipping fee surcharges.

Conclusion 4-2: State-based landfill tipping fee surcharges can provide a dedicated revenue source to support recycling programs and can provide incentives for waste diversion from landfills (especially recyclable materials and organics). As such, landfill tipping fee surcharges can offset some of the costs of recycling, enhance social and environmental benefits associated with recycling, and provide stable financing for recycling systems.

Key Policy Option 4-3: State governments could implement mandatory surcharges on landfill tipping fees to provide incentives for recycling, support recycling and composting efforts, and divert waste from landfills. Moderate surcharges would minimize harmful responses (e.g., illegal dumping, increased contamination of recycling streams). State governments could collect and redistribute the funds to various recycling activities based on state and local priorities. Local uses of these revenues may vary with needs but could include grants for recycling infrastructure, shoring up enterprise funds for recycling operations, and funding local social modeling programs.

Conclusion 4-3: Relying on local government financing limits access to recycling programs, particularly for residents of rural areas, where recycling costs may be high. Alternative funding mechanisms, such as state or federal grants or EPR programs, would help distribute recycling costs across a broader population.

Key Policy Option 4-4: The U.S. Congress and state legislatures could authorize and appropriate funds for rural and tribal recycling. These funds could help communities overcome transportation distances and economies of scale through purchase of infrastructure such as trucks, drop-off and transfer facilities, and processing facilities. In parallel, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency could continue to provide Solid Waste Infrastructure for Recycling grants for rural and tribal communities. State government funding could be derived from revenues generated from extended producer responsibility policies, landfilling tipping fee surcharges, or other state-based revenues.

Materials and Markets Considerations for an Effective Recycling System

In the United States, most communities focus on five material types that are collected curbside or at drop-off centers and processed at MRFs: plastics, paper, cardboard, glass, and metals. Less commonly collected in a separate stream are food and yard wastes. Unique or specific challenges and considerations arise for recycling each material type. For example, plastic is a ubiquitous component of today’s manufactured items because of its strength, low cost, durability, and wide range in properties with dozens of types of plastic resins in use. In particular, recycling plastics is important because of their persistence in the environment, their generation from non-renewable sources, their contribution to litter problems, and more. However, the overall recycling rates for all plastics are low, partly because only certain resin types are accepted for recycling, as influenced by market demand and technological limitations.

Conclusion 5-1: A revenue-neutral policy that applies a fee for using virgin plastic resins and a reward for using recycled plastic resins would increase the cost-competitiveness of recycled materials relative to virgin inputs and would enhance end markets for recyclable materials.

Key Policy Option 5-1: The U.S. Congress could enact a new revenue-neutral fee-and-reward policy to increase the competitiveness of recycled materials relative to virgin inputs. It would encourage the use of recycled plastic resins in the manufacturing of plastic packaging and single-use products. This policy could comprise two levers:

- First, the Department of the Treasury, in partnership with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), could implement a new fee on the use of virgin plastic resins in product packaging and in the manufacturing of consumer products, and a corresponding reward for the use of postconsumer recycled plastic resins in those same manufacturing processes. If implemented, this new fee and reward should be paid and received by domestic manufacturers that use plastic resins in their manufacturing processes, should be weight-based, and should be of sufficient value to encourage the use of recycled plastic resins. Market parity can facilitate economic competition between recycled plastic resin and virgin resin.

- Second, the Department of the Treasury, in partnership with EPA and U.S. Customs and Border Protection could impose a new border adjustment fee on fully manufactured imported plastic packaging and single-use products, to be paid by the importer of those products.

If pursued, this policy should be revenue-neutral for the federal government, such that the total annual sum of fees collected equals the total annual sum of rewards distributed. Furthermore, the Department of the Treasury, in partnership with EPA and other relevant parties, would need to study and identify the appropriate levels of fees and rewards to fully encourage the use of recycled plastic resins while minimizing motivations for changing manufacturing locations.

End markets play a critical role in sustaining recycling systems, with higher-value materials such as aluminum containers, cardboard, and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and noncolored high-density polyethylene (HDPE) plastics contributing the most reliable revenues. Sales of recyclable commodities in end markets provide revenues that reduce the expense of recycling for local governments and private parties with revenue-sharing agreements. However, the effect of end markets is not exclusively financial, because end uses also impact the environment as a benefit of recycling. The extent to which recycling improves environmental quality depends on the successful substitution of secondary materials for extraction or production of environmentally damaging primary materials and when these recycled materials can be incorporated into new products without requiring resource-intensive processing. To this end, improving product recyclability and developing new uses for recycled materials with consideration for reducing environmental costs and enhancing end markets is an area for further research. Thus, end markets and programs to support them need to be assessed for both their financial and environmental benefit.

Conclusion 5-2: Advancing research and development in technology areas relevant to recycling and adopting new technologies in the MSW recycling system can help achieve multiple policy objectives for recycling:

- enhancing end markets for recyclable materials,

- increasing the cost-competitiveness of recycled materials relative to virgin inputs,

- improving the cost-effectiveness of recycling collection and processing,

- decreasing contamination of post-consumer recycling streams, and

- enhancing social and environmental benefits associated with recycling.

Conclusion 5-3: Increased recycling collection may have little benefit without end uses for the collected materials that are environmentally sound and economically valuable. Thus, increased collection needs to be combined with support for end markets, with attention to the environmental implications of end uses.

Key Policy Option 5-2: Federal agencies that fund research related to recycling, including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Energy, and the National Science Foundation, could enhance investments in research related to recycling systems and recyclable materials. When this option is pursued, the research should prioritize environmentally sound and economically valuable end uses for recycled commodities and other approaches to increase end use values nationally and internationally. Examples include recyclable design for consumer products, and technologies to reduce contamination of the recycling material stream. Funding from Congress to support this endeavor could include public–private partnerships in manufacturing innovation to increase opportunities for recyclable materials end uses.

Consumer and Social Impacts of Recycling Programs

Understanding how and why individuals engage or do not engage in recycling practices is crucial for designing policies that effectively increase participation rates and improve recycling outcomes. Household recycling behavior is shaped by various factors, including the availability and accessibility of recycling programs, convenience, public awareness, and economic incentives. While consumer surveys consistently find high support among respondents for recycling and its programs, they also highlight barriers—mainly a lack of convenience and confusion over what materials can be recycled. Inconsistent and misleading packaging labels, including the use of the chasing arrows symbol and resin identification codes, are significant causes of consumer uncertainty and misunderstanding.

Conclusion 6-1: Reforming product labeling regulations and practices to provide accurate information (i.e., to prevent mislabeling) on what products are or are not recyclable would achieve multiple policy objectives, including clarifying information for consumers, decreasing contamination, and increasing efficiency of recycling systems.

Recommendation 6-1: The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) should revise its Guides for the Use of Environmental Marketing Claims so that resin identification codes no longer use the chasing arrows symbol. Additionally, FTC should prohibit use of the chasing arrows symbol or any other indicator of recyclability on products and packaging unless the items are regularly and widely collected and processed for recycling across the United States. Furthermore, with or without a mandate to do so, producers should adopt and use updated resin identification symbols that do not include the chasing arrows symbol.

Key Policy Option 6-1: The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), in partnership with producers could support and evaluate national recycling label standards—through education, out-

reach, and funding—such as the How2Recycle symbols created by the Sustainable Packaging Coalition. Additionally, the U.S. Congress, through EPA, could provide funding for small- to medium-sized companies that lack capability for transitioning to a new national recycling label standard.

Additionally, the presence of social norms and community engagement can further influence participation in recycling efforts. Social modeling programs or locally-organized programs that promote recycling norms and behaviors may facilitate this engagement. Social norms may be used to design communications that address the concerns and values of a target population. Behavioral interventions that promote recycling and decrease contamination are effective when they target a specific barrier to recycling for a given population of consumers. More regular collection and reporting of direct observations of household and commercial behavior related to recycling are needed to support recycling policy decision-making. As one example, new and more rigorously collected data on household time costs are needed to perform recycling cost-benefit analyses more accurately.

Conclusion 6-2: Social modeling programs are effective interventions for enhancing recycling behavior and establishing positive recycling norms in communities. Policies that promote social modeling programs can achieve various objectives for recycling. They can clarify information for consumers, decrease contamination, increase the cost-effectiveness of recycling collection and processing, and enhance the social and environmental benefits associated with recycling.

Recommendation 6-2: The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency should provide grants for state, municipal, local, and tribal governments for enhancing and expanding local social modeling programs, especially in disadvantaged communities and communities with high numbers of multifamily dwellings. Local governments, in turn, should implement or support social modeling programs, potentially through partnership with local nonprofits or other community-based groups, to engage directly with community members to promote positive social norms and recycling practices.

Key Policy Option 6-2: The U.S. Congress could reauthorize and further appropriate funds to the Consumer Recycling Education and Outreach Grant Program, authorized in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, to support social modeling programs.

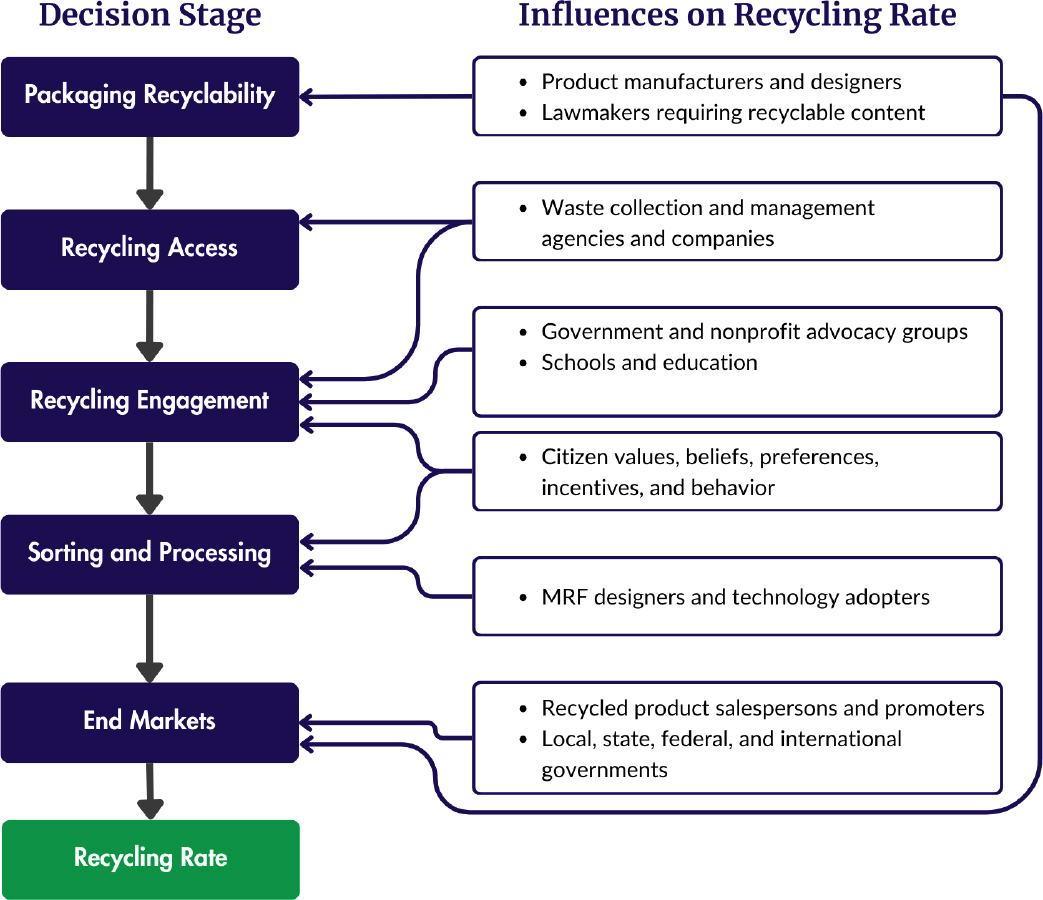

Recycling rates vary significantly across the United States, with some cities achieving higher efficiency through mandates, specialized programs, and focused public policies; these cities demonstrate the potential for recycling efficiency to surpass national averages through targeted local actions. Different actors and pressures—including consumer behavior, economics, and available technology—govern the rate of recycling at different decision stages within the MSW system as well as the costs associated (Figure S-2). These represent key areas where policy choices can positively influence recycling rates.

Different contexts and recycling programs require tailored policy solutions, based on such factors as variations in materials, geographies, economies of scale, existing infrastructure and programs, and demographics and other social considerations. Guiding policies from higher levels of government can be appropriate, but it is necessary to consider and tailor policies for recycling based on local factors. Although they serve an important function, today’s recycling programs sit at a crossroads. In recent years, challenges facing municipal solid waste recycling programs, especially economic-based challenges, have led some municipalities to stop funding their recycling programs altogether. This report explores the contemporary issues facing MSW recycling programs and lays out recommendations and policy options to chart a path forward.

NOTE: MRF = materials recovery facility.

SOURCE: Data from The Recycling Partnership, 2024.

__________________