Reducing Conflicts Between Turning Motor Vehicles and Bicycles: Decision Tool and Design Guidelines (2024)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

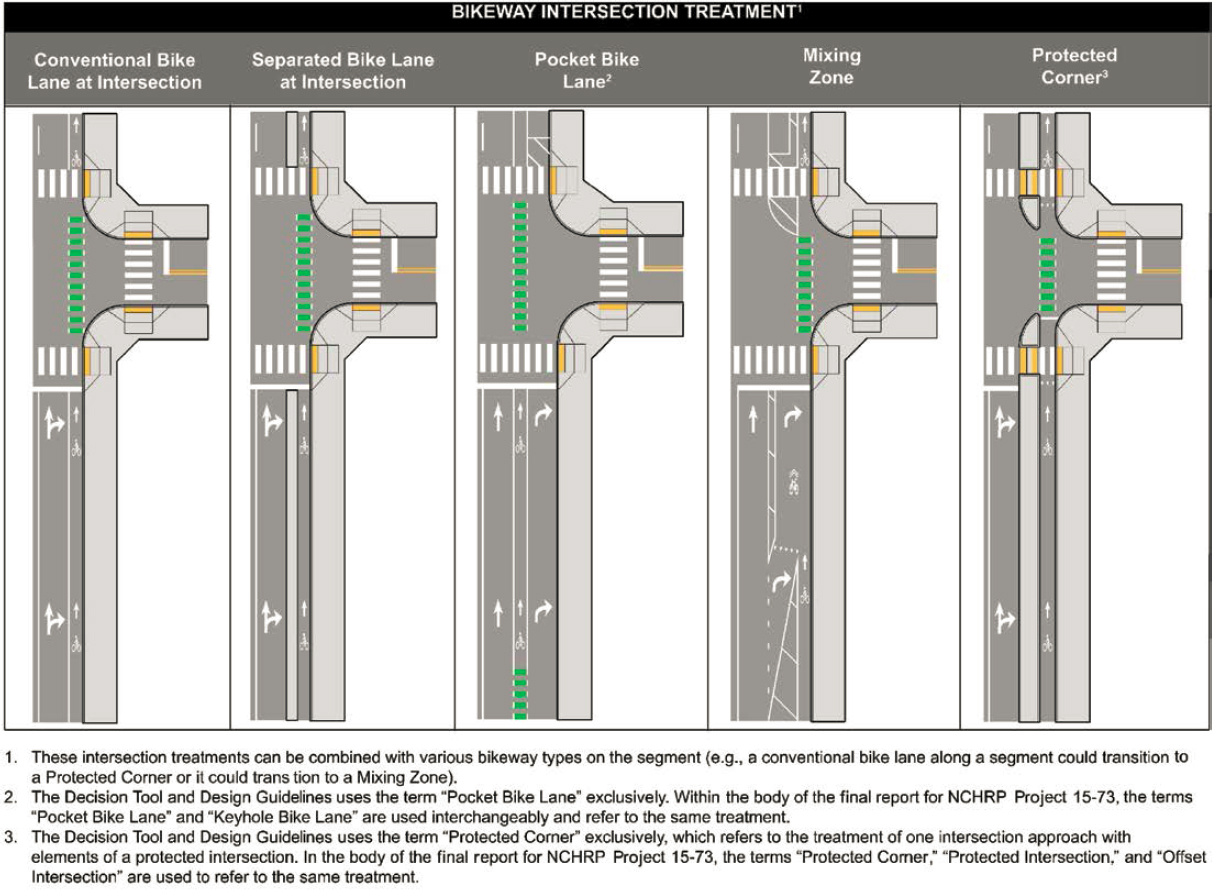

The objective of this research, NCHRP Project 15-73, “Design Options to Reduce Turning Motor Vehicle–Bicycle Conflicts at Controlled Intersections,” was to develop guidelines and tools for transportation practitioners to reduce and manage conflicts between bicyclists and motorists turning at signalized intersections. The research team completed original research (including crash analysis, video-based conflict analysis, and a human factors study) to better understand the effects of known common risk factors, like vehicle volume, vehicle speed, and bicyclist volumes and the relative safety performance of five different intersection treatments: (1) conventional bike lane at intersection, (2) separated bike lane at intersection, (3) pocket bike lane, (4) mixing zone, and (5) protected corner. These five treatments were selected for study based on the critical knowledge gaps identified through the literature review and practitioners and recognition of the project’s time and budget constraints. There are additional intersection treatments that are available for practitioners to implement at intersections that were not studied as part of this project, including bikeways with two-way bicycle traffic (e.g., two-way separated bike lanes and shared-use paths), raised crossings, left-turn phasing, bicycle boxes, two-stage bicycle turn boxes, and roundabouts.

The decision tool and supplemental design guidelines shared in this report provide practitioners an expanded framework for the assessment of trade-offs and decision-making for various intersection treatments to manage conflicts between bicyclists and right-turning motorists. These guidelines incorporate the safety performance of treatments while considering bicyclists’ perceived comfort, which can affect if and where people will ride bikes. Conflicts between bicyclists and right-turning motorists were the focus of the original research, so right-turn conflicts are also the focus of this decision tool. The document acknowledges the significance of left-hook crashes and includes references to the existing body of knowledge and state of the practice for managing left-turn conflicts.

Project Process

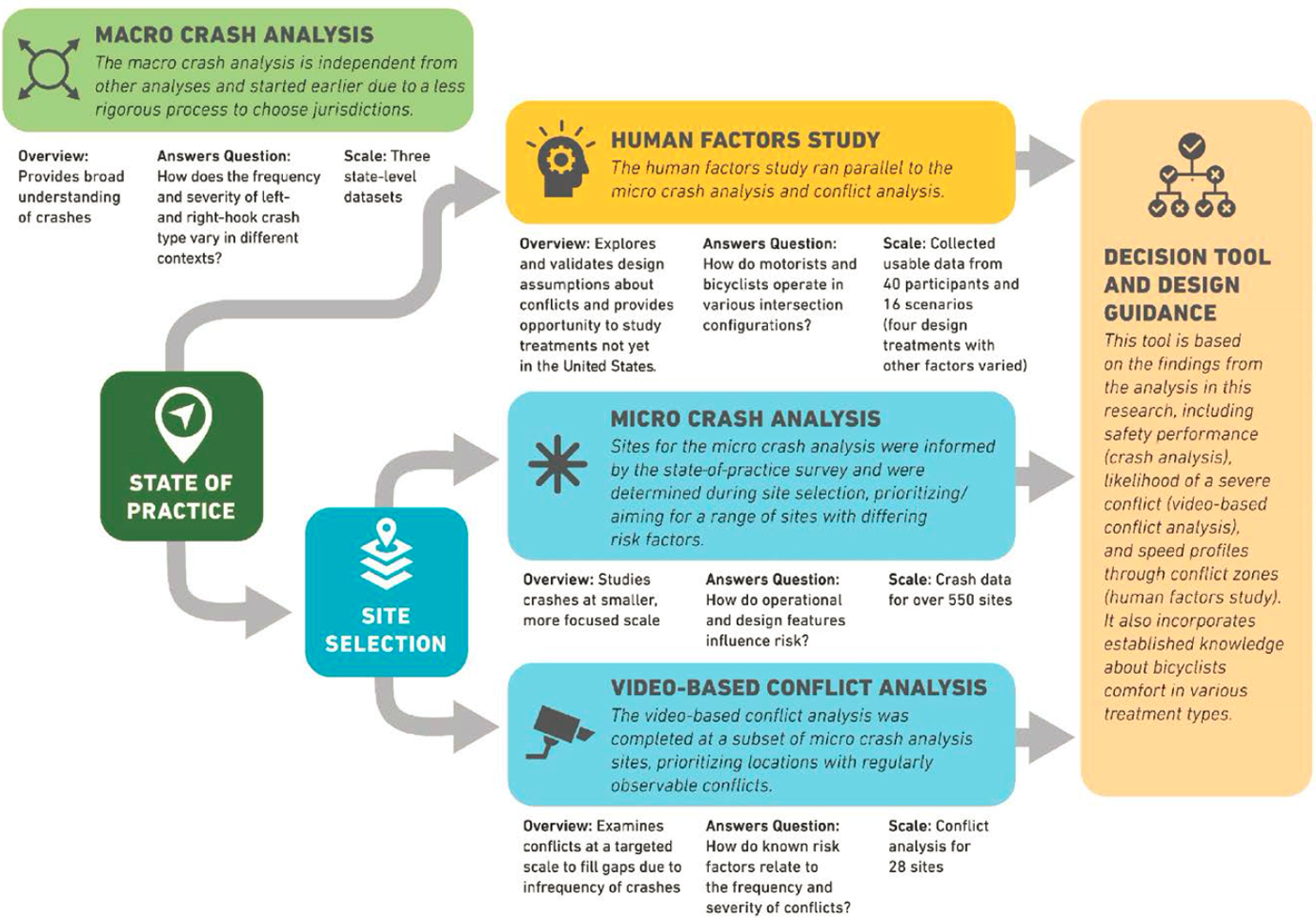

This project began with a documentation of the state of the practice that established the current body of knowledge and gaps in research with respect to managing conflicts between turning motorists and bicyclists at intersections and developed recommendations for future study in phase 2 of NCHRP Project 15-73. It included a summary of design guidance, relevant published literature, and targeted interviews. After the state of the practice was complete, the project team used three research approaches to explore the safety performance of intersection treatment types for bicycles at intersections: (1) crash analysis; (2) video-based conflict analysis; and (3) human factors study (driving simulator). The sites for the crash analysis and video-based conflict analysis were selected from the four case cities: Austin, Texas; Minneapolis, Minnesota; New York City, New York; and Seattle, Washington. Figure 1 provides a visual depiction of how

the different analyses relate to each other, an overview of the primary questions answered, and the scale of each approach.

State of the Practice

The research team produced a state of the practice review to identify the current body of knowledge and gaps in research regarding managing conflicts between bicyclists and motor vehicles turning at signalized intersections and to develop recommendations for future study. The review included a summary of design guidance, a literature review, and the findings from targeted interviews of practitioners at 16 agencies who plan, design, and implement bicycle facilities.

The reviewed design guidance provided general principles to frame decisions, typical applications for treatments, and design details. However, available guidance generally lacked thresholds (e.g., vehicle volume, vehicle speeds, bicycle volumes) to help practitioners understand potential safety risks or benefits when selecting design treatments. The literature review highlighted limitations of crash data as related to bicycle safety (e.g., low frequency of crash events, incomplete injury information, and inaccurate coding of crashes) and suggested that conflicts are correlated with crashes, but the strength of the correlation is still unknown, especially for vulnerable users. The data also highlighted that bicycle and vehicle volumes (through and turning) are strongly correlated with crash frequency. Also, higher right-turn volumes are associated with increased bicycle crash frequency and decreased bicyclist stated comfort. Right-hook crashes are a frequent crash type at intersections but tend to be less severe as compared to left-turn crashes, which may be less frequent but more severe. No research was found that correlates motorist turning speed to bicycle crash frequency or severity.

Although previous studies have shown acceptable safety performance (measured by number of conflicts) for mixing zones, many interested-but-concerned bicyclists may avoid routes that include mixing zones because they are not considered to be high-comfort facilities. For this reason, previous safety studies may not show how the full range of users would navigate these treatments and, therefore, may not reveal their actual safety performance.

Studies in the United States that examine protected intersections have been limited because of the small sample size of sites available; however, international research suggests good safety performance for this intersection treatment. Research conducted by using driving simulators also has shown improved driver performance at protected intersections.

The targeted interviews provided insight into how practitioners across the United States select bikeway treatments for intersections. Agency staff are installing a variety of treatments but are eager for more information. Most agency staff consider a variety of factors (e.g., pedestrian volume, motor vehicle speed, turning vehicle volume, and motor vehicle and bicycle volumes) when determining which treatments to install. Several agencies use or are actively considering using thresholds when selecting design treatments, and some expressed the need for thresholds beyond what is currently available.

Safety Analysis Methods

The safety analysis was designed to gain insights into design-level questions uncovered in the state of the practice review. The research was designed to provide information on relative safety performance of intersection treatments for use in the development of the decision tool. Each method produced valuable information; however, the differing scale, strengths, and disadvantages of each approach mean that synthesizing the results required interpretation and judgment. Table 1 compares the three safety analysis methods. Practitioners can refer to the

Table 1. Safety analysis methods.

| Methods | Scale | Strengths | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Micro-crash analysis | 4 cities 573 sites 233 crashes |

Direct measure of safety | Inconsistent data quality Bicycle crashes are rare events Does not account for the bias from people using or not using certain facilities |

| Video-based conflict analysis | 4 cities 28 sites 2,167 hours of video 16,107 interactions (i.e., conflicts with varying severity) |

Robust, objective conflict data Large sample size |

Conflicts are difficult to define consistently with metrics No established direct correlation between conflicts and crashes Does not account for the bias from people using or not using certain facilities |

| Human factors study (driving simulator) | 40 participants 640 turns 28,800 seconds of data (i.e., 8 hours) |

Controlled experiment No site limitations Detailed event and driver information/data |

Requires participant recruitment Challenge translating performance measures to safety and design decisions Practical limit on number of variables to explore due to participant fatigue |

final report for additional details on the research methods. Based on the results of the state of the practice review, the site selection focused on the five different intersection treatment types shown in Figure 2.

Interpretation of Safety Analysis Findings

The decision tool was developed by combining interpretations of the findings from the original research that was completed as a part of NCHRP Project 15-73 related to crash performance, likelihood of a severe conflict, and speed at conflict point, which are each described below. It also incorporated previous research related to bicyclist comfort of different intersection treatment types. The decision tool used findings and interpretations from the body of research to provide guidelines for practitioners on recommendations for intersection treatments based on safety performance trade-offs and known risk factors (e.g., motor vehicle volume, bicyclist volume, percentage of heavy vehicles, and intersection geometry).

The following factors are discussed in Table 2, which provides a high-level summary of the research results and conclusions for how the findings were incorporated into the decision tool. Practitioners can refer to the final report for additional details on the research findings.

- Crash performance—the number of observed vehicle–bicycle crashes on the intersection approach per 1,000 bicyclists. The results for Austin, Texas (AUS); Minneapolis, Minnesota (MSP); and Seattle, Washington (SEA) were combined and evaluated separately from results for New York City (NYC) because built environment patterns and bicyclist volumes—both of which impact crash likelihood—are substantially different in NYC compared to the other cities.

- Speed at conflict point—the mean vehicle speed at the conflict point.

- Likelihood of severe conflict—the predicted number of severe conflicts based on hourly bicycle and hourly turning-vehicle volumes for each of the intersection treatments studied.

- Bicyclist comfort—the likelihood of a bicyclist being comfortable in the treatment type (Monsere et al. 2019).

Table 2. High-level safety analysis findings.

| Conventional Bicycle Lane at Intersection | Separated Bicycle Lane at Intersection | Pocket Bicycle Lane | Mixing Zone | Protected Corner |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conclusion for Decision Tools | ||||

| Only recommended once practitioners have made every effort to reallocate space to provide a protected corner or separated bicycle lane at intersection | Preferred treatment (with leading interval or full-phase separation in some conditions) |

Only recommended in limited situations | Only recommended if right-turning motor vehicle volumes are high and practitioners have made every effort to reallocate space to provide a right-turn lane and separated bicycle lane at intersection | Preferred treatment (with leading interval or full-phase separation in some conditions) |

| Crash Performance | ||||

| Second highest crash rate in AUS, MSP, and SEA [0.342 crashes per year per 1,000 bicyclists] Similar crash rate as pocket bike lane in NYC [0.336 crashes per year per 1,000 bicyclists] |

Highest crash rate in AUS, MSP, and SEA [0.774 crashes per year per 1,000 bicyclists] Second highest crash rate in NYC [0.260 crashes per year per 1,000 bicyclists] (Limitation: exposure models may not fully capture number of bicyclists using streets with these treatments) |

Second lowest crash rate in AUS, MSP, and SEA [0.183 crashes per year per 1,000 bicyclists] Second lowest crash rate in NYC [0.246 crashes per year per 1,000 bicyclists] |

Lowest crash rate in AUS, MSP, and SEA [0.073 crashes per year per 1,000 bicyclists] Second lowest crash rate in NYC [0.204 crashes per year per 1,000 bicyclists] (Limitation: likely highly confident bicyclists are primary users, which may contribute to mixing zones having comparable performance to a protected corner) |

Middle crash rate in AUS, MSP, and SEA [0.310 crashes per year per 1,000 bicyclists] Lowest crash rate in NYC [0.190 crashes per year per 1,000 bicyclists] (Limitation: small sample sizes, especially outside of NYC) |

| Likelihood of Severe Conflict | ||||

| Second highest predicted number of conflicts [3.1 predicted # severe conflicts/h for 50 bicyclists/h and 150 turns/h] |

Lowest predicted number of conflicts [0.4 predicted # severe conflicts/h for 50 bicyclists/h and 150 turns/h] |

Highest predicted number of conflicts [14.5 predicted # severe conflicts/h for 50 bicyclists/h and 150 turns/h] |

Second lowest predicted number of conflicts [0.9 predicted # severe conflicts/h for 50 bicyclists/h and 150 turns/h] (Limitation: same as crash performance. Additionally, mixing zones in conflict analysis had short mixing zones. Designs with longer conflict areas may have more conflicts.) |

Similar number as a mixing zone [1.3 predicted # severe conflicts/h for 50 bicyclists/h and 150 turns/h] (Limitation: same as crash performance) |

| Speed at Conflict Point | ||||

| Moderate mean speeds at conflict point [10.25 mph] |

Moderate mean speeds at conflict point [9.74 mph] |

Highest vehicle speed at the conflict point [14.61 mph] |

Lowest mean speed at the conflict point [7.27 mph] |

Second lowest mean speed at conflict point [7.90 mph] |

| Bicyclist Comfort | ||||

| People bicycling prefer more separation than a conventional bike lane at intersections. | People bicycling are comfortable at intersections that maintain separation to the intersection. | People bicycling are the least comfortable in pocket bicycle lanes and mixing zones. | People bicycling are the least comfortable in pocket bicycle lanes and mixing zones. | People bicycling are the most comfortable at locations with a protected corner. |