Reducing Conflicts Between Turning Motor Vehicles and Bicycles: Decision Tool and Design Guidelines (2024)

Chapter: 4 Supplemental Design Guidelines

CHAPTER 4

Supplemental Design Guidelines

The discussion in this chapter provides recommendations for mitigating known safety concerns for each intersection treatment.

Shared Lane

For streets and intersections where bicyclists are operating in a shared lane with motorists, unless the street is a bike boulevard where volumes and speeds are low, designers should recognize that most bicyclists operating in a shared lane will typically be highly confident bicyclists as the road may not meet the needs of the interested-but-concerned bicyclists. If a shared lane condition is provided, the following treatments should be considered:

- Keep vehicle operating speeds low (25 mph or less is desirable; 35 mph max) to maximize comfort and safety. Consider traffic-calming elements, including vertical deflection (e.g., speed humps, speed lumps), that are comfortable for bicyclists to traverse. Sinusoidal profile of these treatments is preferable.

- Consider green wave signal timing to align corridor progression with the speeds of bicyclists.

- Where the bikeway passes through a signalized intersection, the signal detection should be able to detect the presence of a bicycle and provide the required minimum green and change and clearance intervals for the bicyclist to traverse the intersection.

- Install shared lane markings within the outside travel lanes. A black background may be considered to enhance contrast. If shared lane markings are used to supplement signs, the shared lane markings should be installed in the center of the travel lanes.

- Provide “Bikes Allowed Use of Full Lane” signs to reinforce a bicyclist’s right to the road and to provide an indication to motorists to expect bicyclists operating within the travel lane.

- In locations where there is space available, add a short segment of conventional bike lane approaching the intersection to allow bicyclists to bypass queued cars and provide access to a bicycle box.

Conventional Bike Lane at Intersection

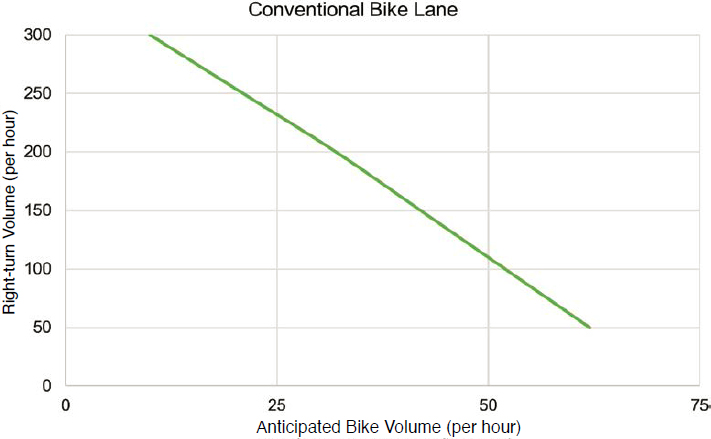

The Conventional Bike Lane at Intersection treatment has limited applications at intersections in a high-comfort bikeway network. As shown in the decision tool flow chart, practitioners should make every effort to find space to provide a separated bike lane at the intersection. In this research, separated bike lanes had almost half the number of severe conflicts and substantially fewer crashes. Additionally, the conflict analysis showed that severe conflicts at conventional bike lanes are more sensitive to increases in bike volumes compared to other treatments. Therefore, conventional bike lanes are often only appropriate in locations with lower

bicycle volumes (i.e., when the combination of bicyclist and right-turn motorist volumes is below the line in Figure 9). If a conventional bike lane is provided, the following treatments should be considered:

- Keep motor vehicle turning speeds low using small corner radii, curb extensions, and mountable truck aprons, where appropriate.

- Dash the lane line along the bike lane to communicate that motorists may merge into the bike lane on the intersection approach, particularly if turning motorist volumes exceed 50 veh/h. These dashed lines may be supplemented with green-colored pavement to communicate to motorists and bicyclists that this is a potential conflict point.

- Dash the lane extension line through the intersection to communicate to motorists and bicyclists that this is a potential conflict point. These dashed lines may be supplemented with green-colored pavement to further emphasize the potential conflict point.

- At locations with higher volumes of turning motorists (e.g., greater than 150 veh/h) or higher speeds (e.g., greater than 35 mph), consider providing a bicycle ramp in advance of the intersection to allow bicyclists to exit the roadway to an off-street bikeway before the intersection conflict.

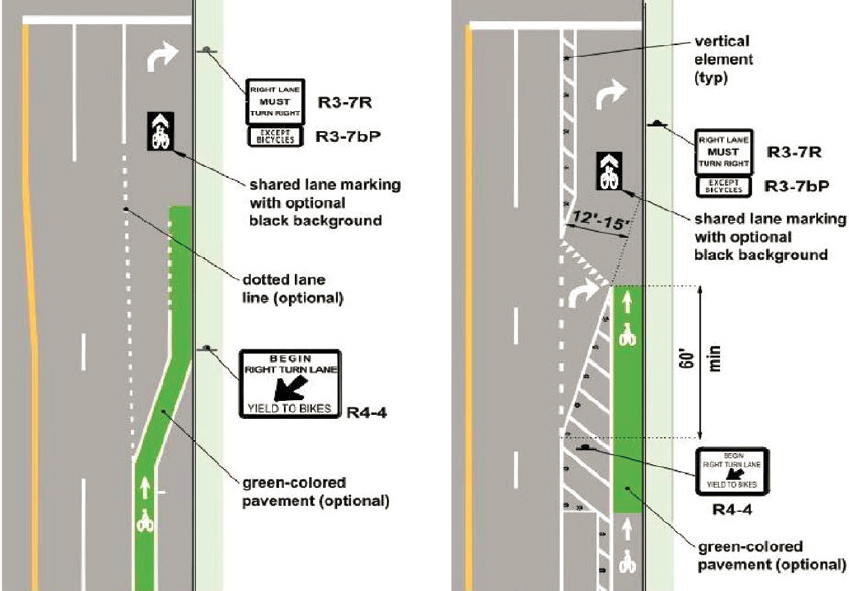

Mixing Zone

Mixing zones can be implemented at locations where it is determined that a right-turn lane is necessary for vehicular capacity, but there is not enough space to maintain a separated bike lane along the right-turn lane. Mixing zones require motorists and bicyclists to navigate a shared space and are not preferred by interested-but-concerned bicyclists. Providing a mixing zone will reduce the comfort and safety along an all-ages-and-abilities bikeway, and some people may choose not to bike at all if confronted with this treatment on their biking route. Mixing zones also provide a large conflict area between bicyclists and turning motorists located in advance of the intersection, where motorists’ speeds are higher. While mixing zones have the lowest crash rates other than protected corners and have the lowest predicted number of crashes, it is likely that more risk-tolerant bicyclists (i.e., those comfortable enough to be in the mix with motor

vehicle traffic) are most users at these intersections. If a mixing zone is provided, the following treatments should be considered:

- Treatments to mitigate speeds at conflict points will help reduce the potential severity of crashes within a mixing zone. These treatments may include providing the shortest length of right-turn lane to move the conflict points closer to the intersection and to provide a painted buffer with flex posts between the travel lane and the right-turn lane to shorten the entry point for motorists into the turn lane and help to control speeds.

- Install shared lane markings within the right-turn lane. A black background may be considered to enhance contrast.

- For streets with on-street parking, consider restricting parking in advance of the intersection to improve visibility between users.

- For higher-speed locations or locations where the right-turn lane is longer, the option shown on the right in Figure 10 can be implemented to reduce the length of the turn lane, where bicyclists and motorists are mixed.

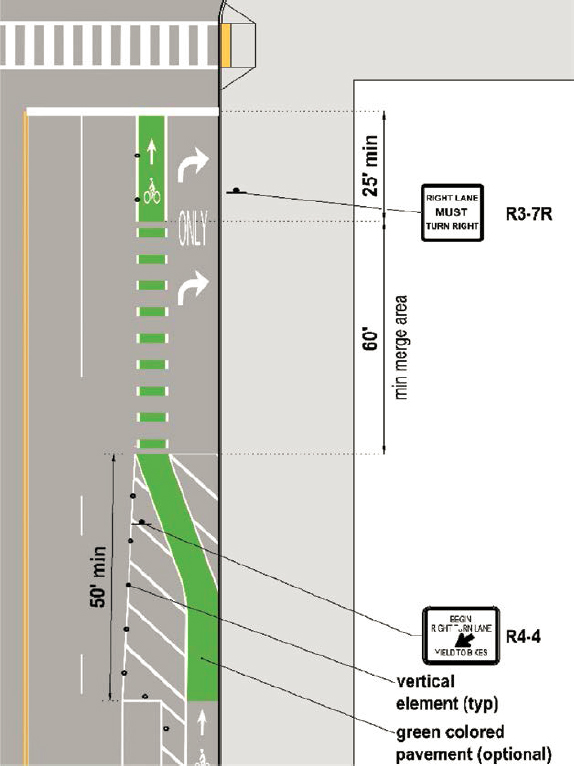

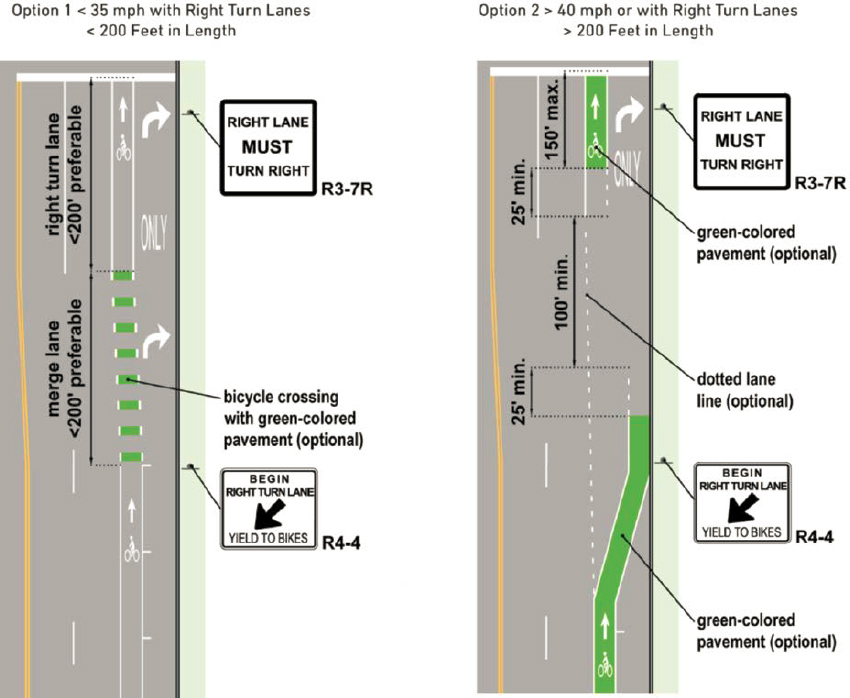

Pocket Bike Lane

Pocket bike lanes provide a space for bicyclists to bypass right-turning motorists but require them to travel between an active through lane and a right-turn lane. Crash data suggest that pocket bike lanes are relatively safer than conventional bicycle lanes because they were associated with fewer crashes; however, the conflict data show higher user speeds and higher-severity conflicts, and the simulator data show movements that negate the benefits of the treatment type. Taken together, these findings indicate that this treatment type may not be appropriate for an

all-ages-and-abilities network because of the need to consistently watch for and negotiate with motorists for safe passage. Pocket bike lanes should be applied only in limited locations to provide an opportunity for bicyclists to bypass the queue of right-turning motorists where the volumes of bicyclists are low (fewer than 20 bicycles/h) and where right-turning motorist speeds are low. If a pocket bike lane is provided, the following treatments should be considered:

- Treatments to mitigate speeds at the conflict area will help to reduce the potential severity of crashes where bicyclists transition into the pocket bike lane. These treatments may include providing the shortest length of right-turn lane to move the conflict points closer to the intersection and to provide a painted buffer with flex posts between the motorist through lane and bike lane to shorten the entry point for motorists into the turn lane, help control speeds, and provide some comfort for bicyclists (see Figure 11).

- At particularly high volume or high-speed conflict points (e.g., highway on- and off-ramps) or locations with long turn lanes (greater than 200 ft), consider providing a bicycle ramp in advance of the intersection to allow bicyclists to exit the roadway to an off-street bikeway before the intersection conflict. Another option is to retain the bike lane along the right side of

- the long turn lane and provide the transition to the pocket bike lane closer to the intersection where motorist speeds are lower (see Figure 12).

- The bike lane and the transition into the pocket bike lane may be supplemented with green-colored pavement to clearly communicate to motorists to expect bicyclists, to provide way-finding guidance for bicyclists, and to communicate the entry point into the right-turn lane.

- For streets with on-street parking, consider restricting parking in advance of the intersection to improve visibility between users.

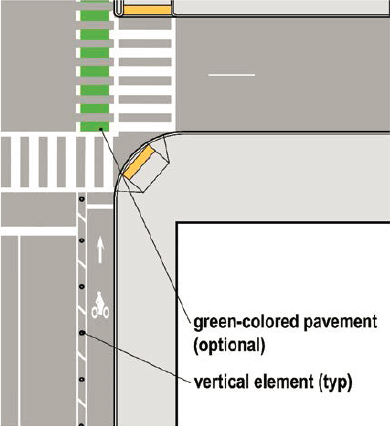

Separated Bike Lane at Intersection

The Separated Bike Lane at Intersection treatment (see Figure 13) provides a space for bicyclists to bypass right-turning motorists and provides a place for bicyclists to queue outside of the path of turning motorists. The conflict point between bicyclists and turning motorists is located at the intersection, where motorist turning speeds are lower. The Separated Bike Lane at Intersection treatment has similar crash performance to that of the Conventional Bike Lanes at Intersection since its limited buffer width creates similar right-hook conditions for the two intersection treatments. Separated Bike Lane at Intersection safety is noticeably worse than that of Protected Corners, particularly as the volume of right-turning motorists increases. Protected

corners are preferred to separated bike lanes at intersections, but if it is not possible to provide a protected corner because of geometric constraints, the following treatments should be considered:

- Maximize the width of the separated bike lane buffer to provide some additional motorist yielding space (like a protected corner).

- Ensure that the vertical elements located within the separated bike lane buffer extend as far into the intersection as possible to control the speeds of turning motorists at the conflict point while still accommodating the design vehicle’s turning movement.

- Provide full or partial phase separation to reduce the potential for conflict, particularly at higher-volume locations.

- Locate the bicyclist stop bar ahead of the motorist stop bar to improve the visibility of bicyclists.

- Dash the lane extension line through the intersection to communicate to motorists and bicyclists that this is a potential conflict point. These dashed lines may be supplemented with green-colored pavement to further emphasize the potential conflict point.

- For streets with on-street parking, consider restricting parking in advance of the intersection to improve visibility between users.

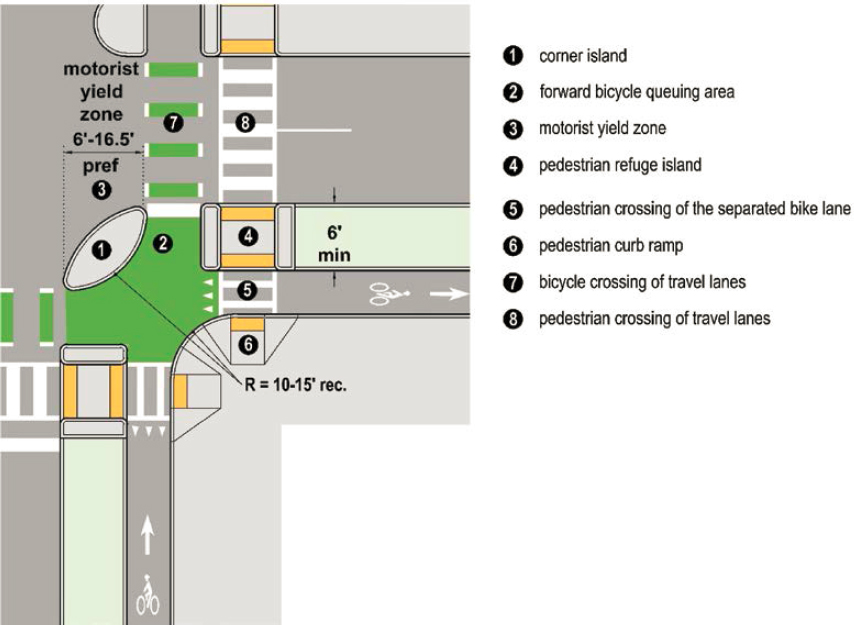

Protected Corner

Protected corners provide a space for bicyclists to bypass right-turning motorists and a place to queue outside of the path of turning motorists (see Figure 14). The conflict point between bicyclists and turning motorists is located at the intersection, where motorist turning speeds are lower, and at a location that maximizes visibility between motorists and bicyclists. The Protected Corner treatment has low crash rates, a low potential for conflicts (particularly as volumes of right-turning motorists increase), and the most consistent low-speed conflict point. Although protected corners provide safety and comfort benefits for bicyclists, these designs can still benefit from additional countermeasures to further address safety and comfort. If a protected corner is provided, the following treatments should be considered:

- An offset of 6 to 16.5 ft from the adjacent travel lanes is identified as the ideal offset to maximize motorist yielding and provide visibility of and for bicyclists; however, where turning volumes are high, travel speeds are high, or where left-turning motorists have concurrent movements, a 20-ft offset can be considered.

- Ensure that the corner radius of the protected corner is as small as possible. Where larger radii are needed to accommodate a larger design vehicle, consider the use of a mountable truck apron to facilitate those movements while controlling the speeds of smaller vehicles.

- Ensure that suitable approach clear space is provided so that bicyclists and motorists can see each other and respond accordingly. This may include restricting on-street parking or larger sight obstructions near the intersection.

- Provide full or partial phase separation to reduce the potential for conflict, particularly at higher-volume locations.

- Locate the bicyclist stop bar ahead of the motorist stop bar to improve the visibility of bicyclists.

- Dash the lane extension line through the intersection to communicate to motorists and bicyclists that this is a potential conflict point. These dashed lines may be supplemented with green-colored pavement to further emphasize the potential conflict point.

- For streets with on-street parking, stopping parking in advance of the intersection will improve visibility between users.

Full or Partial Phase Separation

The decision tool provides recommendations for instances when reducing or eliminating conflicts between bicyclists and turning motorist vehicles by means of traffic signal phasing should be considered. Full separation provides time for bicyclists to traverse the intersection and eliminates turning motorist vehicle conflicts. Full separation strategies require the general-purpose

lane adjacent to the bikeway to have a red indication, and bicyclists to have a green indication. An adjacent right-only lane typically results in more time allocated to the bike phase but may come at the expense of space provided to the bikeway. When the adjacent general-purpose lane is a combination through and right-turn lane, using full separation strategies can result in a minimal amount of time allocated to the bicycle movement and increased delay for bicyclists and motorists. With this strategy, it is important to keep in mind that when the average bicyclist’s delay exceeds 30 s, bicyclists’ compliance with signal indications may be reduced, and, therefore, the potential for conflicts is greater (HCM 2010). This may be addressed by reducing signal cycle lengths and providing progression speeds along the corridor that more closely align with bicyclists’ speeds.

A leading bicycle interval not only provides time for bicyclists to traverse the intersection without turning motor vehicle conflicts but also allows concurrent bicycle through and turning motorist movements to occur after the leading bicycle interval lapses. This strategy allows bicyclists waiting at the intersection to proceed without conflicts and allows bicyclists who arrive to the intersection later in the phase to proceed through the intersection in conflict with turning motorists. This strategy can reduce the total number of potential conflicts and similarly benefits from reducing signal cycle lengths and providing progression speeds that more closely align with bicyclist speeds.

Although this research focused on right-turn conflicts, left-turn movements have additional complexities, and research has indicated that a significant portion of motorists making left turns during permissive movements are focused on finding a gap in traffic and may not be looking for crossing cyclists. Also, because of higher turning speeds, left-hook crashes tend to be more severe than right-hook crashes. For these reasons, signal strategies that phase separate left-turn movements are recommended. Phase separation for dual left-turn lanes is always required, regardless of whether the turn lanes cross a bikeway or not. ODOT’s Multimodal Design Guide (2022) provides additional details of phase separation strategies and signal timings that accommodate bicyclists. Restricting right turns on red should be considered where full phase separation or leading bicycle intervals are implemented. Additionally, pedestrians will benefit from the removal or reduction of conflicts when signal phasing is implemented for bicyclists.

Additional Intersection Solutions and Treatments

There are a variety of design treatments that this decision tool and design guidelines do not consider, including roundabouts, speed-limit reductions and traffic-calming elements, raised crossings for bicyclists, left-turn signal phasing, and two-way bicycle facilities. While these treatments should be considered where appropriate, these elements were beyond the scope of the research and as such are not directly included. That said, the following provides a brief synopsis of why these treatments might be considered along with relevant resources.

- Roundabouts: This intersection type can be beneficial by reducing all motorist speeds within the intersection and by converting all left-turn movements into right-turn movements. When seeking to accommodate the interested-but-concerned bicyclist, consideration should be given to maintaining bikeway separation from the adjacent general-purpose travel lanes. Multilane roundabouts require additional consideration for bicyclist comfort as well as pedestrian accessibility. NCHRP Report 1043: Guide for Roundabouts (Kittelson & Associates, Inc. et al. 2023) and the U.S. Access Board’s Accessibility Guidelines for Pedestrian Facilities in the Public Right-of-Way (36 CFR Part 1190) provide additional design consideration for roundabouts.

- Reducing speed limit: Motorist speed is a significant factor in the likelihood of a crash with a bicyclist resulting in either limited or no injury or in a serious or fatal crash. The FHWA Safe System Approach for Speed Management (FHWA 2023b) provides recommendations for

- establishing target speeds that align with the Safe System Approach and recommending changes to streets to establish operating speeds that more closely align with those targets. FHWA’s Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways (2023a) provides guidance on the various methods of setting speed limits.

- Raised crossings: Establishing raised crossings for bicyclists (and pedestrians) can help to communicate that bicyclists (and pedestrians) have a right-of-way priority, while also serving as a traffic-calming treatment for both left- and right-turning motorists. The Multimodal Design Guide (ODOT 2022) provides guidance on the benefits of raised crossings as well as design details based on target speeds.

- Left-turn phasing: Left-turning motorists can present a higher-speed crash risk to bicyclists compared to right-turning motorists because left-turning motorists tend to have a higher rate of acceleration toward the conflict point. This risk factor increases as the number of lanes the motorist must turn across increases due to the workload of the driver looking for gaps in approaching traffic. While phase separating these conflicts should always be considered, the Multimodal Design Guide (ODOT 2022) provides recommended threshold volumes and conditions where phase separating should always be considered.

- Two-way bicycle facilities: Two-way bikeways include two-way separated bike lanes and shared-use paths. When located along a roadway, these facility types introduce a contraflow movement for bicyclists that has been shown to increase bicyclist crash rates. Because of this increased crash risk, one-way bikeways are preferable to two-way bikeways. When it is determined that a two-way bikeway is desirable, the intersection design should focus on the potential conflicts with this contraflow movement. The ODOT Multimodal Design Guide (2022) discusses the conditions where a two-way bikeway may be desirable and provides guidance on intersection designs that should be considered.