Reducing Conflicts Between Turning Motor Vehicles and Bicycles: Decision Tool and Design Guidelines (2024)

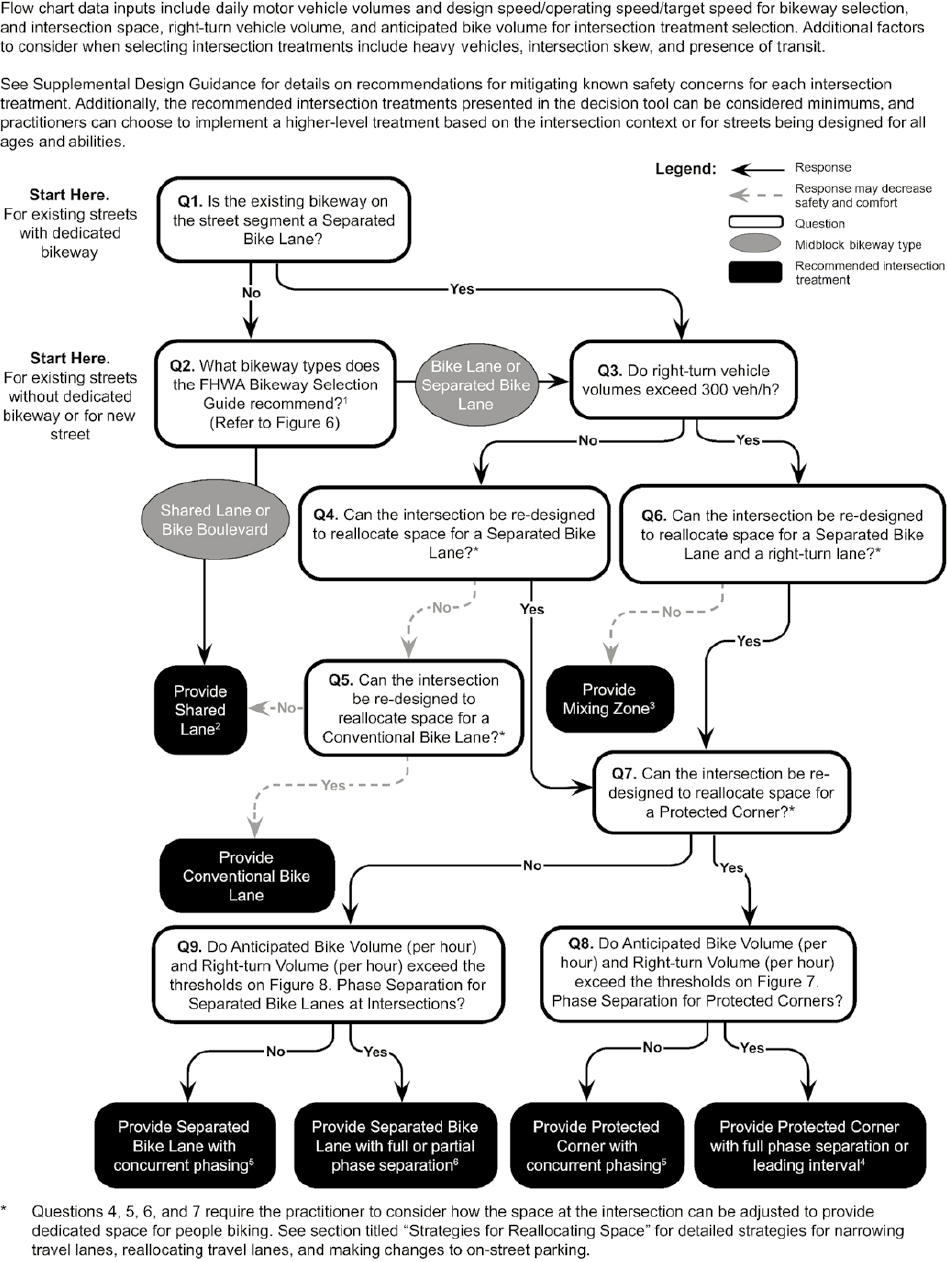

Chapter: 3 Intersection Bikeway Design Decision Tool

CHAPTER 3

Intersection Bikeway Design Decision Tool

The decision tool provides guidelines related to urban, suburban, and rural town center land-use contexts. It is not intended for use in rural areas outside of town centers unless those bicycle routes are intended to accommodate the interested-but-concerned bicyclist. The research completed as a part of NCHRP Project 15-73 focused on evaluating safety performance of the five intersection treatments described previously for bikeways with one-way bicycle traffic. Two-way separated bike lanes, shared-use paths, and side paths are additional bikeway types that can be considered in a bikeway network and are not addressed in these design guidelines; however, practitioners should recognize that these types of two-way bikeways introduce a contraflow movement for bicyclists that often increases the need to separate bicyclists from motor vehicles at intersections by providing protected corners and eliminating conflicts with motor vehicles using traffic signal phase separation or grade separation. For additional details on implementing and designing these additional bikeway types, refer to FHWA’s Bikeway Selection Guide (2019) and Separated Bike Lane Planning and Design Guide (2015) and NACTO’s Urban Bikeway Design Guide (2014).

Using the Decision Tool

This decision tool focuses on the primary risk factors most likely to affect safety outcomes for bicyclists. Motor vehicle right-turning volumes and bicyclist total volumes are the primary factors discussed within the decision tool, primarily because these were the risk factors that were prominent in the research.

The decision tool provides a starting point for assessing intersection design options to accommodate the needs of interested-but-concerned bicyclists. Practitioners should review factors like crash history; documented public complaints, including near misses; intersection corner radius and resulting motor vehicle turning speeds; available sight distances; and other factors that can influence driver or bicyclist behavior and safety outcomes. The recommended intersection treatments presented in the decision tool can be considered minimums, and practitioners may choose to implement a higher-level treatment based on the intersection context. If practitioners are designing to accommodate the needs of bicyclists of all ages and abilities, a higher-level treatment should be considered. Finally, there are additional treatments that may be implemented in addition to those recommended in this decision tool.

This decision tool and design guidelines research report does not provide comprehensive guidance on design or bikeway network planning. Suggestions in this document should be used in conjunction with other existing guidelines and standards, such as the Bikeway Selection Guide (FHWA 2019), the Urban Bikeway Design Guide (NACTO 2014), Designing for All Ages & Abilities (NACTO 2019a), Don’t Give Up at the Intersection (NACTO 2019b), the Manual on Uniform Traffic

Control Devices for Streets and Highways (FHWA 2023a), AASHTO’s Green Book (AASHTO 2018), and the Highway Capacity Manual 2010 [HCM (2010)]. In several places, the decision tool and supplemental design guidelines refer to the Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) Multimodal Design Guide (ODOT 2022). The fifth edition of AASHTO’s Guide for the Development of Bicycle Facilities (i.e., the AASHTO Bike Guide) will include specific design guidance for all the treatments mentioned in this decision tool as well as basic bikeway design considerations; however, at the time of publication of this decision tool and design guidelines, the fifth edition of the AASHTO Bike Guide has not yet been published and, thus, could not be referenced. The ODOT Multimodal Design Guide is referenced in this document for additional design details for bicycle lane widths and signal design as it is generally consistent with the forthcoming edition of the AASHTO Bike Guide on these topics.

Background Data Needs

Practitioners should have the following information available for use with the decision tool:

- For use in bikeway selection for the segment:

- Motor vehicle daily volumes (i.e., either a recent 24-h count or average annual daily traffic)

- Motor vehicle design speed, operating speed, and target speed

- For use in a decision tool flowchart for intersection treatment selection:

- Motor vehicle hourly right-turning volumes (i.e., peak hours at a minimum, additional hours are preferred).

- Note: Left-turning volumes are not a factor in the decision tool because the research and decision tool were focused on managing conflicts between bicyclists and right-turning motorists.

- Existing or anticipated hourly bicycle volumes (through and turning volumes combined).

- Note: There may be instances when bicycle volumes are not available or where it is expected for bicycle volumes to increase when a roadway or bikeway is upgraded to a higher-comfort bikeway. Individual agencies may have existing demand models or a count program to estimate bicycle volumes. Alternatively, practitioners could select a design volume based on an assumed number of bicyclists per signal cycle (e.g., if one assumes one bicycle per cycle and the cycle length was 90 s, then that would correspond to 40 bicyclists per hour). Finally, an agency could base the estimated number of bicyclists using mode split goals for their community.

- Street geometry, specifically street widths

- Motor vehicle hourly right-turning volumes (i.e., peak hours at a minimum, additional hours are preferred).

- Additional considerations for intersection treatment selection:

- Heavy vehicle volumes and percentages

- Street geometry, specifically presence of intersection skew

- Bus stop locations

Decision Tool Step-by-Step Guide

This section supports the flowchart (Figure 5) by providing additional explanation for each of the questions, including how they relate to each other, and directing practitioners to other areas of this document for additional details.

- For existing streets with a dedicated bikeway, start with Question 1 (Q1): Is the existing bikeway a Separated Bike Lane?

- If yes, proceed to Question 3, which asks about right-turn volumes across the bikeway.

- If no, proceed to Question 2, which asks about what bikeway type FHWA’s Bikeway Selection Guide recommends.

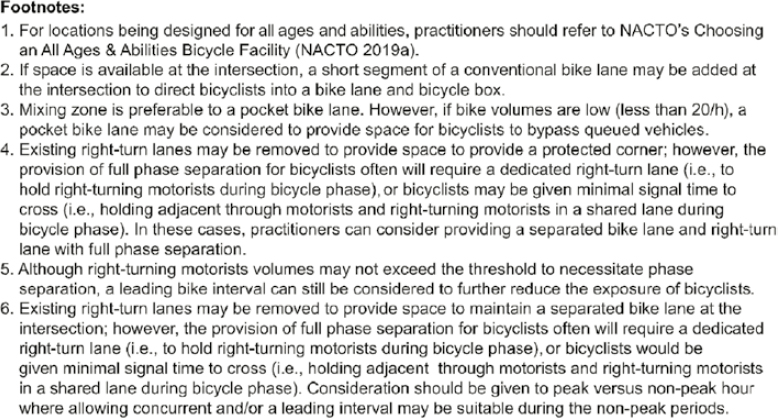

- For existing streets without a dedicated bikeway or for new streets (e.g., a street being constructed as part of a new development), start with Question 2 (Q2): What bikeway types does the FHWA Bikeway Selection Guide recommend? (FHWA 2019). The Bikeway Selection Guide provides guidance on selecting the appropriate bikeway type based on motor vehicle speeds, motor vehicle volumes, and contextual factors (e.g., heavy vehicle percentages, parking turnover, land-use context); see Figure 6, which is from the Bikeway Selection Guide. Practitioners should consider if the street is part of a planned bicycle network and if the project goals accommodate interested-but-concerned bicyclists or all ages and abilities. See the section on Considering Bicycle Design Users in Design Decisions in Chapter 2 for additional details. For locations being designed for all ages and abilities, practitioners should refer to NACTO’s Choosing an All Ages & Abilities Bicycle Facility chart (NACTO 2019a).

- If Shared Lane or Bike Boulevard, provide a shared lane. Refer to the supplemental design guidance section Shared Lane in Chapter 4.

- If Bike Lane or Separated Bike Lane, proceed to Question 3, which asks about right-turn volumes across the bikeway.

- Question 3 (Q3): Do right-turn vehicle volumes exceed 300 veh/h [vehicles per hour]? This question is one of the few questions, including Questions 8 and 9, that help decide if a right-turn lane is needed. Even if an existing right-turn lane is present, practitioners should not assume it is necessary and consider removing the right-turn lane to provide space for a separated bike lane at intersection treatment or to provide a protected corner. For this question, practitioners should screen for the need for a right-turn lane using thresholds of 300 veh/h for the right-turning vehicles. This threshold is based on two factors: the HCM provides a guideline that a right-turn lane is needed when right-turn volumes exceed 300 veh/h (HCM 2016); however, for the purpose of this assessment, the decision tool user’s agency may have different policies. Also, phase separation is recommended for intersections with more than 300 right-turning veh/h, based on the charts in Questions 8 and 9.

The decision to provide a right-turn lane has commonly been driven by the desire to increase vehicular capacity, not only by adding a lane but also by increasing the ability for right-turn-on-red movements. Right-turn lanes have also been installed to reduce rear-end crashes on higher-speed roads. However, this approach is not appropriate in locations where bicyclists are being accommodated. Specifically, the desire to reduce rear-end crashes, typically a lower-severity crash, should be weighed against the potential for a motor vehicle–bicycle crash and comfort of people biking as a part of a Safe System Approach. While a right-turn lane may

- be desirable to reduce delay for motorists during the peak hour, removing the right-turn lane and providing a protected corner may be appropriate to increase safety for bicyclists during all hours of the day. In other scenarios, a right-turn lane may be needed to provide full or partial signal phase separation (i.e., leading interval) between turning motor vehicles and bicyclists. Where bicycle through movements and motor vehicle right-turn movements are partially or fully phase separated, a right-turn lane may be necessary.

- If yes, proceed to Question 6, which asks whether the intersection can be redesigned to reallocate space to provide a right-turn lane and a separated bike lane at intersection.

- If no, proceed to Question 4, which asks whether the intersection can be redesigned to reallocate space to accommodate a separated bike lane at intersection.

- Question 4 (Q4): Can the intersection be redesigned to reallocate space for a Separated Bike Lane at intersection? This question is focused on whether it is possible to either maintain a separated bike lane at the intersection for locations with existing separated bike lanes on the street segment (i.e., answered “Yes” to Q1) or at locations where a bike lane or separated bike lane is being added based on the answer to Q2.

Adequate street space for separated bike lanes at intersections can be achieved through a variety of interventions, such as reallocating general-purpose lanes, narrowing travel lanes (even if it would require a design waiver or variance), changing on-street parking, reallocating a planted buffer or furnishing strip, adjusting sidewalk width, or acquiring additional

- right-of-way. See the following discussion on strategies for reallocating space for additional details. The width will depend on street buffer width, anticipated number of bicyclists, the desire to accommodate frequent passing or side-by-side riding, and the curb type. Additional details on bike lane and street buffer widths can be found in the Multimodal Design Guide (ODOT 2022). Further, the decision about whether there is enough space should include an assessment of the operational changes for motorists and safety benefits for bicyclists during peak and off-peak hours, recognizing that in most cases a decision to accommodate a higher level of service for motorists during a brief peak period will have negative consequences for bicyclist safety throughout the day. In a Safe System Approach, design decisions should prioritize safety for all street users over convenience for one street user.

- If yes, proceed to Question 7, which asks whether the intersection can be redesigned to reallocate space for a protected corner.

- If no, proceed to Question 5, which asks whether the intersection can be redesigned to reallocate space for a conventional bike lane at intersection.

- Question 5 (Q5): Can the intersection be redesigned to reallocate space for a Conventional Bike Lane at Intersection? If the answer to Q4 (i.e., Can the intersection be redesigned to reallocate space to provide a Separated Bike Lane at Intersection?) was “No,” practitioners next need to determine whether there is space to provide a conventional bike lane. A conventional bike lane requires a minimum of 5 ft (4 ft in constrained settings).

- If yes, provide a conventional bike lane at intersection. Refer to the supplemental design guidelines section Conventional Bike Lanes in Chapter 4. Conventional bike lanes provide no protection for bicyclists at intersections and are considered a lower-comfort facility that may compromise the ability for the street to be a part of a high-comfort bikeway network, especially for locations where the FHWA Bikeway Selection Guide recommends a separated bike lane.

- If no, provide a shared lane. Refer to the supplemental design guidelines section Conventional Bike Lanes in Chapter 4. Shared lanes require bicyclists to mix with motorists and are considered a lower-comfort facility that may compromise the ability for the street to be a part of a high-comfort bikeway network, especially for locations where the FHWA Bikeway Selection Guide recommends a bike lane or separated bike lane.

- Question 6 (Q6): Can the intersection be redesigned to reallocate space for a Separated Bike Lane at Intersection and a dedicated right-turn lane? If the answer to Q3 (i.e., Do right-turn vehicle volumes exceed 300 veh/h?) was “Yes,” practitioners next need to determine whether there is space to maintain the bikeway as a separated bike lane at intersection along the right-turn lane. The space for the separated bike lane along the right-turn lane can be provided by removing general-purpose travel lanes, narrowing travel lanes, or changes to on-street parking. See the following discussion on Strategies for Reallocating Space for additional details.

- If no, then provide a mixing zone. Mixing zones are considered a lower-comfort facility and will compromise the ability for the street to be a part of a high-comfort bikeway network. See the supplemental design guidelines section Mixing Zone in Chapter 4 for design details to reduce risk and maximize comfort. A mixing zone is preferable to a pocket bike lane. However, if bike volumes are low (less than 20/h), a pocket bike lane may be considered to provide space for bicyclists to bypass queued vehicles. See the supplemental design guidelines section Pocket Bike Lane for design details to reduce risk and maximize comfort.

- If yes, then proceed to Question 7 to determine whether the intersection can be redesigned to reallocate space for a protected corner.

- Question 7 (Q7): Can the intersection be redesigned to reallocate space for a Protected Corner? If the answers to Q4 (i.e., Is there enough space to provide a Separated Bike Lane at Intersection?) or Q6 (i.e., Is there space to provide a separated bike lane and a right-turn lane?) were “Yes,” practitioners next need to determine whether there is space to provide a protected

- corner before considering whether phase separation is needed. Details on dimensions required for a protected corner can be found in the ODOT Multimodal Design Guide (ODOT 2022).

- If yes, then proceed to Question 8, which evaluates the need for phase separation at an intersection with a protected corner.

- If no, then proceed to Question 9, which evaluates the need for phase separation at an intersection where a separated bike lane is maintained to and through the intersection.

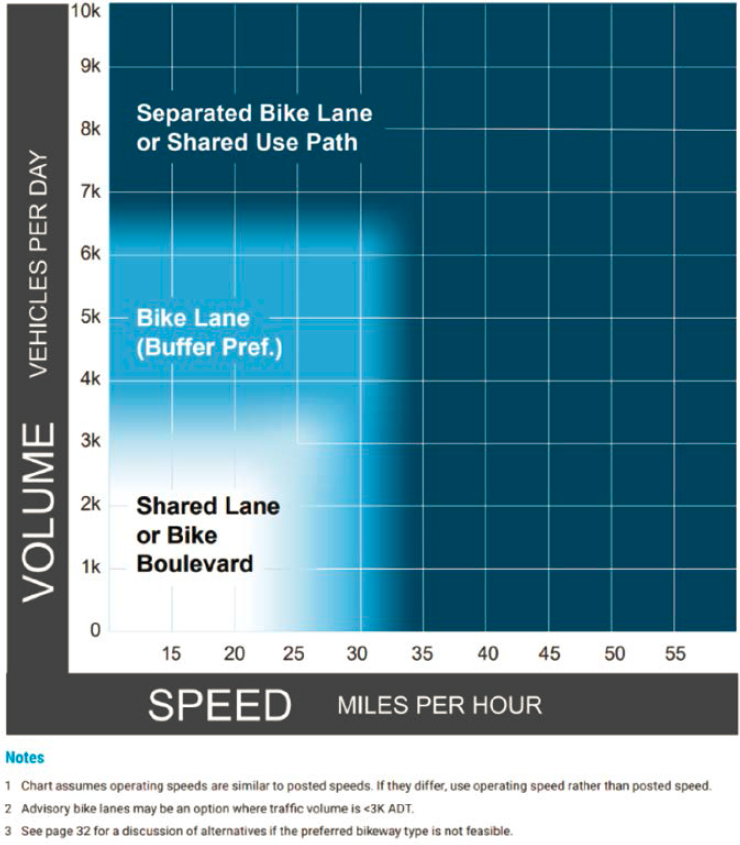

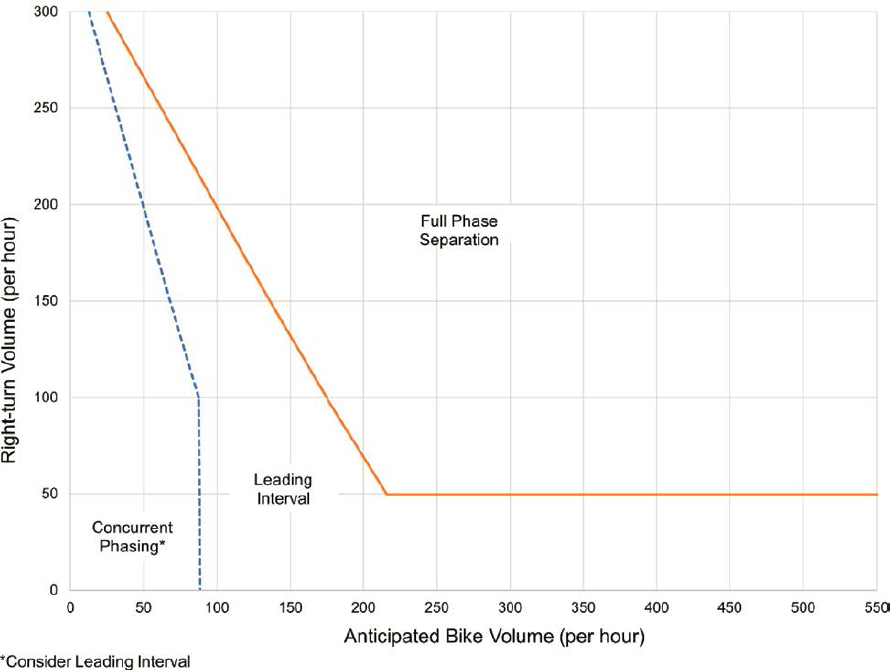

- Question 8 (Q8): Do volumes exceed the thresholds on the “Protected Corner Signal Phasing Thresholds” chart? Even if there is space to provide a protected corner, it may be desirable to provide a leading interval or full phase separation for locations with higher bicycle and vehicle volumes (Figure 7). See additional details on considerations for phase separation in the upcoming section on full or partial phase separation. If the percentage of heavy vehicles is greater than 5 percent or there is a desire to further reduce the potential for conflicts, signal strategies with more phase separation should be considered, even if the chart does not indicate the need for a leading interval or full phase separation. Finally, protected corners also have the benefit that they have shorter crossing distances for bicyclists, which results in shorter phase length needs for bicyclists. They also have the benefit of accommodating left-turn movements for bicyclists at intersections where two separated bike lanes intersect.

- If volumes fall above the orange line, a protected corner and full phase separation is recommended. Existing right-turn lanes may be removed to provide space to provide a protected corner; however, the provision of full phase separation for bicyclists often will require a dedicated right-turn lane (i.e., to hold right-turning motorists during bicycle phase) or by giving bicyclists the minimal signal time to cross on their own dedicated phase (i.e., holding adjacent through motorists and right-turning motorists in a shared lane during bicycle phase). In these cases, practitioners can consider providing a separated bike lane at the intersection and right-turn lane with full phase separation.

- If volumes fall above the blue dashed line, but below the orange line, a protected corner and a leading bike interval is recommended.

-

- If volumes fall below the blue dashed line, provide a protected corner and concurrent phasing. Although right-turning motorists’ volumes may not exceed the threshold to necessitate phase separation, a leading bike interval can still be considered to further reduce the exposure of bicyclists.

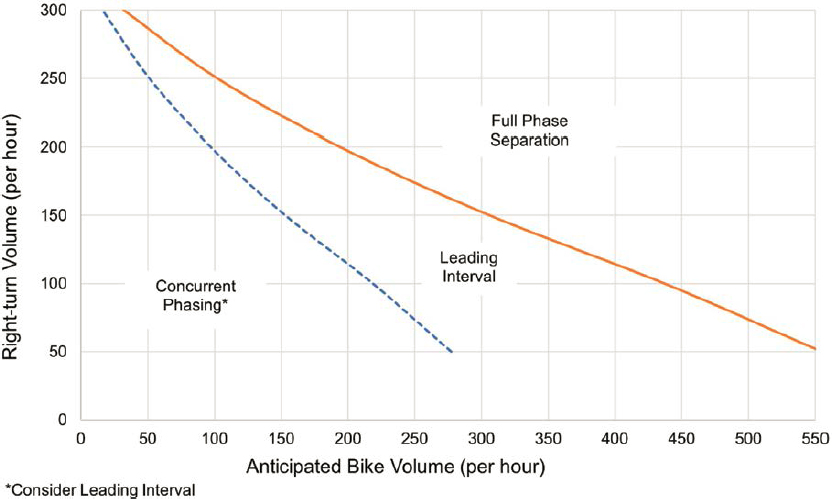

- Question 9 (Q9): Do volumes exceed the thresholds on the “Separated Bike Lane at Intersection Signal Phasing Thresholds” chart? If there is space to provide a separated bike lane at the intersection but not enough for a protected corner, practitioners are asked to determine whether phase separation is needed at an intersection where a separated bike lane is maintained to and at the intersection. Figure 8 provides thresholds for whether a leading bike interval or full phase separation is recommended at an intersection. These thresholds are lower than the thresholds for locations with a protected corner. If the percentage of heavy vehicles is greater than 5 percent or there is a desire to further reduce the potential for conflicts, signal strategies with more phase separation should be prioritized.

- If volumes fall above the orange line in Figure 8, a separated bike lane at the intersection and full phase separation is recommended. Existing right-turn lanes may be removed to provide space to maintain a separated bike lane at the intersection; however, the provision of full phase separation for bicyclists often will require a dedicated right-turn lane (i.e., to hold right-turning motorists during bicycle phase) or giving bicyclists minimal signal time to cross (i.e., holding adjacent through motorists and right-turning motorists in a shared lane during bicycle phase). Consideration of peak-hour versus non-peak-hour operations

-

- should be given if allowing concurrent phasing, or a leading interval may be suitable during the non-peak periods.

- If volumes fall above the blue dashed line but below the orange line in Figure 8, a separated bike lane at the intersection and leading bike interval is recommended.

- If volumes fall below the blue dashed line, a separated bike lane at intersection and concurrent phasing is recommended. Although right-turning motorists’ volumes may not exceed the threshold to necessitate phase separation, a leading bike interval can still be considered to further reduce the exposure of bicyclists.

Strategies for Reallocating Space

There are several questions (Q4, Q5, Q6, and Q7) in the decision tool that require users of the guide to consider how roadway space can be reallocated to provide a bikeway or additional buffer space for people biking in a separated bike lane at the intersection. The following content also directs practitioners to additional resources for support in making decisions about reallocating space, including two supplements to the Bikeway Selection Guide (FHWA 2021a, FHWA 2021b). This ability to reallocate space may be informed by the project type and the type of work that can be performed. In a roadway reconstruction project, the ability to move curblines will often allow for space to be reallocated to provide the recommended facility types. In a retrofit project, or a project occurring as part of a resurfacing program, practitioners might not be able to make modifications to curblines but may be able to repurpose the exiting curb-to-curb width to provide the recommended design.

Narrowing Travel Lanes

Narrowing travel lanes along a roadway or at an intersection can provide space to accommodate a higher-comfort bikeway or intersection treatment. The AASHTO Green Book (AASHTO 2018) provides flexibility in lane widths, allowing a range of 9 to 12 ft depending on context of the roadway and states that 10-ft-wide travel lanes are appropriate on streets with design speeds 45 miles per hour (mph) or lower. The Bikeway Selection Guide (FHWA 2019) and Achieving Multimodal Networks: Applying Design Flexibility & Reducing Conflicts (Porter et al. 2016) emphasize that narrower lanes can contribute to lower operating speeds, do not negatively impact vehicle safety, and have marginal impact on vehicular capacity. A nationwide study of lane widths and safety found no significant difference in nonintersection crashes on streets with speeds of 20–25 mph and lane widths between 9 ft and 12 ft (Hamidi and Ewing 2023). For streets with speeds of 30–35 mph, wider lane widths (10 ft and wider) have more crashes than streets with 9-ft lanes.

In some cases, narrowing the bike lanes to the practical minimum also can be done to provide space for maintaining the separated bike lane or implementing a protected corner. Refer to the Multimodal Design Guide (ODOT 2022) for details on preferred, recommended, and minimum bicycle lane widths.

Reallocating Travel Lanes

Reallocating travel lanes can provide space for prioritizing people biking at an intersection. In some cases, motor vehicle operations and impacts to motor vehicle efficiency can be the focus of an evaluation for lane reallocation, but practitioners should use a holistic approach to evaluating an intersection. Traffic Analysis and Intersection Considerations to Inform Bikeway Selection (FHWA 2021b) emphasizes the importance of using a range of performance measures (e.g., safety, pedestrian and bicycle quality of service metrics, travel time). The resource includes several

techniques related to operational analysis assumptions (e.g., volume projections and growth rates) and interpretation of results (e.g., network utilization and peak spreading). It goes on to include discussion prompts related to operational analysis in support of bikeway selection (FHWA 2021b) that can be used by practitioners for conversations related to lane removal as well as phasing changes at intersections. Decisions related to the number of travel lanes have often been made based on a desire to accommodate a particular level of service for motorists during the peak hour; however, a Safe System Approach to design should acknowledge that designing for optimal motorist conditions during the peak hour will often result in streets that have excess capacity during nonpeak periods (which represent the majority of time throughout the day) and can increase motorist speeds and reduce bicyclist safety and comfort. Roadway Cross-Section Reallocation: A Guide provides recommendations for incorporating all-day performance measures into a street reconfiguration evaluation (Semler et al. 2023).

Making Changes to On-Street Parking

It may be possible to provide space for adding a bike lane, a bike lane buffer, or a separated bike lane or protected corner by reconfiguring parking. One option is to remove parking close to the intersection to add separation to a conventional bike lane or provide a protected corner by bending the bikeway to the edge of the street. FHWA’s Bikeway Selection Guide (2019) provides several common ways to reconfigure parking along the length of a street:

- Removing parking on one side (for streets with parallel parking on both sides of the street)

- Removing parking on both sides of the street (Note: this is not specifically included in the FHWA Bikeway Selection Guide)

- Converting diagonal parking to parallel parking

- Converting parallel parking to reverse-angle parking on one side

- Flipping the location of parking and bike lanes to create a parking-protected separated bike lane

In some communities, there might be resistance from business owners or residents to prioritizing public space for bikeways rather than on-street parking. FHWA’s On-Street Motor Vehicle Parking and the Bikeway Selection Process (2021a) includes a section on strategies to inform discussions about a community’s priorities (i.e., comfort and safety of a bikeway versus providing on-street parking).

Additional Strategies

There are several additional strategies for reallocating space at intersections, including but not limited to reducing the planting or furnishing strip, narrowing the sidewalk, or acquiring right-of-way.

Additional Considerations Impacting Safety and Treatment Selection

Heavy Vehicles

Large trucks and buses are associated with additional risk for bicycle crashes because of the vehicles’ size and mass and the decreased visibility between the motorists and other road user. Research has identified safety risks for bicyclists related to large vehicles at intersections, including intersection complexity and limited visibility (Pokorny et al. 2017; Pokorny and Pitera 2019). Right-hook-style crashes have been identified as a common truck-bicycle crash scenario; bicyclists positioning near the front-turning corner of the truck and in blind spots are a major

contributing factor (Talbot et al. 2017). Studies have also found that a larger number of large vehicles turning at intersections is associated with a higher likelihood of conflicts (Liang et al. 2020), and crashes involving trucks or buses are nearly twice as likely to result in severe injury for the bicyclist (Asgarzadeh et al. 2017; Moore et al. 2011).

At locations where more than 5 percent of the turning traffic is heavy vehicles, full or partial phase separation should be considered as part of the traffic signal strategy. These locations will also benefit from a protected corner or separated bike lane at the intersection to reduce the size of the conflict area to a consistent and predictable location and provide a bicycle queuing area outside the path of turning vehicles. Protected corners also improve visibility between bicyclists and drivers of heavy vehicles. Intersections that must accommodate heavy-vehicle turns will also benefit from the installation of mountable truck aprons to control the turning speeds of motor vehicles while accommodating the space needed for the turning path of larger vehicles. The design treatment identified with a dashed arrow in the decision tool represents a treatment that will reduce the comfort and safety of the bikeway; that safety and comfort will be further reduced in locations with higher heavy-vehicle volumes.

Intersection Skew

Skewed intersections have been shown to increase crash risk between bicyclists and turning motorists where the turning motorist is navigating along the obtuse angle of the intersection. This configuration allows motorists to navigate the turns more quickly, thus increasing the potential severity of the crash. Intersection design that positions conflict points in advance of the intersection (e.g., mixing zones and pocket bike lanes) should be avoided at intersections with these skews. At skewed intersections, the protected corner and separated bike lane at intersection configurations should be prioritized to consolidate conflict points. Also, physical countermeasures should be considered to control the turning speeds of motorists; these countermeasures may include curb extensions, mountable truck aprons, or raised bikeway (and pedestrian) crossings. Full or partial traffic signal phase separation should also be considered because of the potential for higher-severity crashes.

Transit

Interactions between buses and bicycles present unique challenges, and where relatively frequent transit headways occur, they will often result in interactions that negatively impact bicyclists’ level of comfort and safety. As noted in FHWA’s Separated Bike Lane Planning and Design Guide (2015), options for minimizing conflicts with transit include creating floating bus stops that transition a conventional bike lane to a separated bike lane through the bus stop area, placing a bike lane or separated bike lane on the left side of a one-way street (out of the way of transit stops along the right side), or choosing to install a bikeway on a nearby parallel corridor away from transit. Floating bus stops typically can be incorporated into protected corner designs to eliminate conflicts between the transit vehicle and bicyclists and are a preferred design where space permits. On one-way streets, left-side bike lanes performed slightly worse in the crash data analysis but provide more consistent operations by removing conflicts with buses. Protected corners and left-side bike lanes also eliminate the leapfrog effect that occurs in other bike-lane configurations, where a bicyclist passes a bus stopped to board and alight passengers, the bus later passes the bicyclist further along the corridor, the bus again stops in front of the bicyclist, and so on.