Carbon Removal at Airports (2024)

Chapter: 1 Introduction to Carbon Dioxide Removal

CHAPTER 1

Introduction to Carbon Dioxide Removal

This chapter is intended to provide the reader with an understanding of the concept of carbon dioxide (CO2) removal (CDR), how it fits into the aviation industry and net-zero roadmaps, basic principles of carbon markets, and possible methods to address the implementation of CDR relative to the context of carbon markets. (Note: Carbon removal and carbon dioxide removal are used interchangeably in the industry as well as in this report.)

Why Is This ACRP Report Needed?

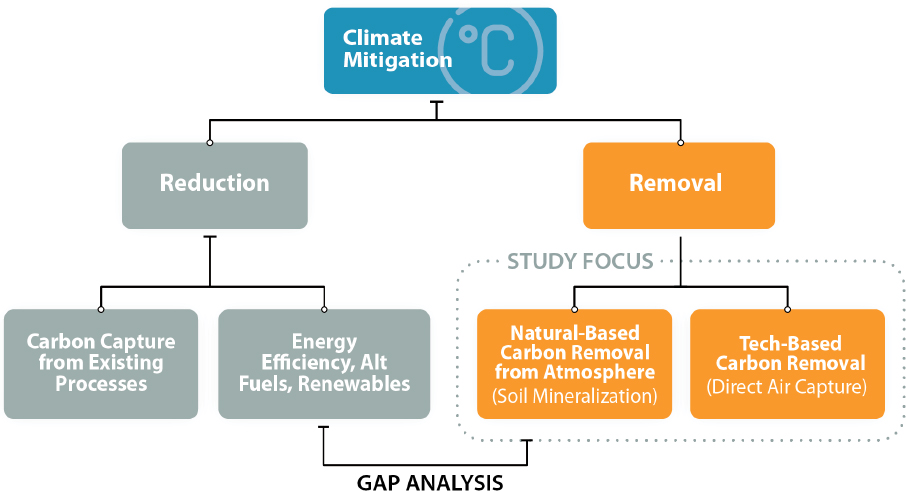

Most ACRP projects undertaken to date have focused on carbon reduction. This report focuses on residual and hard-to-address emissions and how these fit into the larger efforts toward net zero.

This chapter is organized into the following sections:

- Introduction to CDR:

- Net-Zero Integration

- Carbon Removal Versus Carbon Capture

- Types of CDR

- Types of Aviation Emissions

- Aviation Industry—International Organization Goals

- Aviation Industry—Goals

- Airports Net-Zero Roadmaps:

- Airports Council International (ACI) Airport Carbon Accreditation (ACA)

- ACRP Report 11: Guidebook on Preparing Airport Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventories (Kim et al. 2009)

- Links to Previous ACRP Research

- Context of Carbon Markets and CDR Certifications:

- Overview

- Terminology—Carbon Credits and Offsets

- The Compliance Carbon Market (CCM)

- The Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM)

- Insetting Versus Offsetting

- Approval and Certification

- Airports and the Carbon Market

- CDR Ownership Structure

- Lessons Learned from Microsoft

1.1 Introduction to CDR

CDR refers to different strategies, technological or nature-based, that remove CO2 directly from the atmosphere. Fundamentally, CDR involves two key principles: (1) the removal of CO2 molecules from the atmosphere and (2) their storage in biological (e.g., plants and soils), geological, or marine reservoirs or in long-lived products. The removal of CO2 from the atmosphere is intended to be durable or permanent—the terms “durability” and “permanence” are used

interchangeably to refer to carbon storage for a certain time—though the durability varies across different CDR approaches.

The definition of CDR used in this guide follows the three principles identified in The State of Carbon Dioxide Removal (Smith et al. 2023), the first global assessment on the state of CDR:

Principle 1: The CO2 captured must come from the atmosphere, not from fossil sources. The removal activity may capture atmospheric CO2 directly or indirectly, for instance via biomass or seawater.

Principle 2: The subsequent storage must be durable, such that CO2 is not soon reintroduced to the atmosphere.

Principle 3: The removal must be a result of human intervention, additional to Earth’s natural processes. (Smith et al. 2023)

There are many CDR pathways that are categorized by Earth system (e.g., land or marine), storage medium (such as geological formations, minerals, vegetation, soils and sediments, buildings), and type of removal process (land-based biological, ocean-based biological, geochemical, and chemical) (Chiquier et al. 2022). Although many countries, organizations, and industries have set a goal of net zero by 2050, it will not be achieved without deploying technology that actively removes CO2 from the atmosphere. CDR approaches must complement emission-reduction efforts to successfully reach net-zero and net-positive goals (a net-positive goal refers to allowing more CO2 to be removed from the atmosphere than is generated).

To put the need for CDR in context, globally, and specifically for the aviation industry, net-zero goals are unlikely to be met without CDR. The U.S. government’s long-term strategy includes plans for the removal of approximately 1–1.8 billion metric tons of CO2 equivalent (CO2e)—CO2e is the number of metric tons of CO2 emissions with the same global-warming potential as one metric ton of another greenhouse gas (GHG)—annually by 2050 (Choudry 2022). CDR is growing in recognition, and, in fiscal year 2021, investments in the United States reached over $80 million in research and development (R&D) and demonstration for various types of CDR technologies and strategies (Riedl et al. n.d.). Note that different CDR techniques have vastly different costs. For example, direct air capture (DAC) costs approximately $94/t-CO2 to as high as $1,000/t-CO2 removed, while reforestation costs around $50/t-CO2 removed (Choudry 2022; Keith et al. 2018). It is critical to increase R&D and deployment of CDR technologies and to increase the utilization of natural carbon sinks to achieve the ambitious goal of net zero by 2050. Once net-zero goals are achieved, the focus will switch to becoming climate positive, which is defined as removing more atmospheric carbon than one entity emits. The concept of being climate positive correlates to having a positive impact on the climate by removing legacy emissions to avoid the greatest climate-change impacts.

A primary resource for information on CDR is the Carbon Dioxide Removal Primer (Wilcox et al. 2021), which two scientists and multiple contributors from diverse areas spent approximately 2 years researching and writing. The intention behind the primer was to create a common language and compile a collective understanding of CDR needs, technology, and future uses.

1.1.1 Net-Zero Integration

CDR is needed to meet net-zero goals in the aviation industry and globally. Reducing carbon emissions is important and has been the focus of most of the current ACRP studies to date (see the section on gap analysis later in this chapter). However, when it comes to addressing residual and legacy emissions, CDR is widely acknowledged as the solution to address the gap between emissions-reduction measures and reaching a net-zero goal. The delineation of the study focus is illustrated in Figure 5.

1.1.2 Carbon Removal Versus Carbon Capture

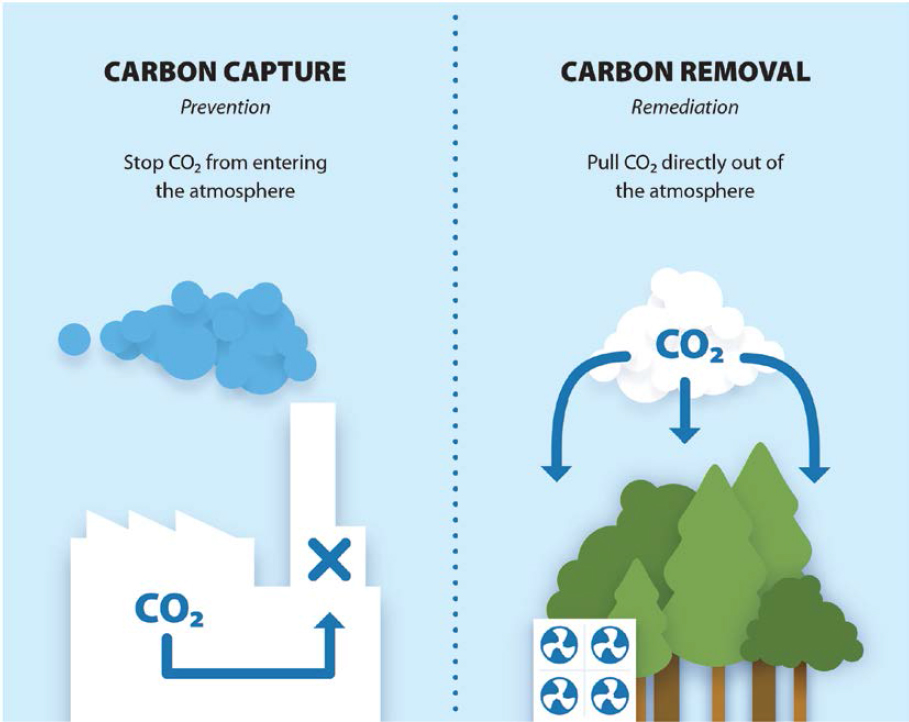

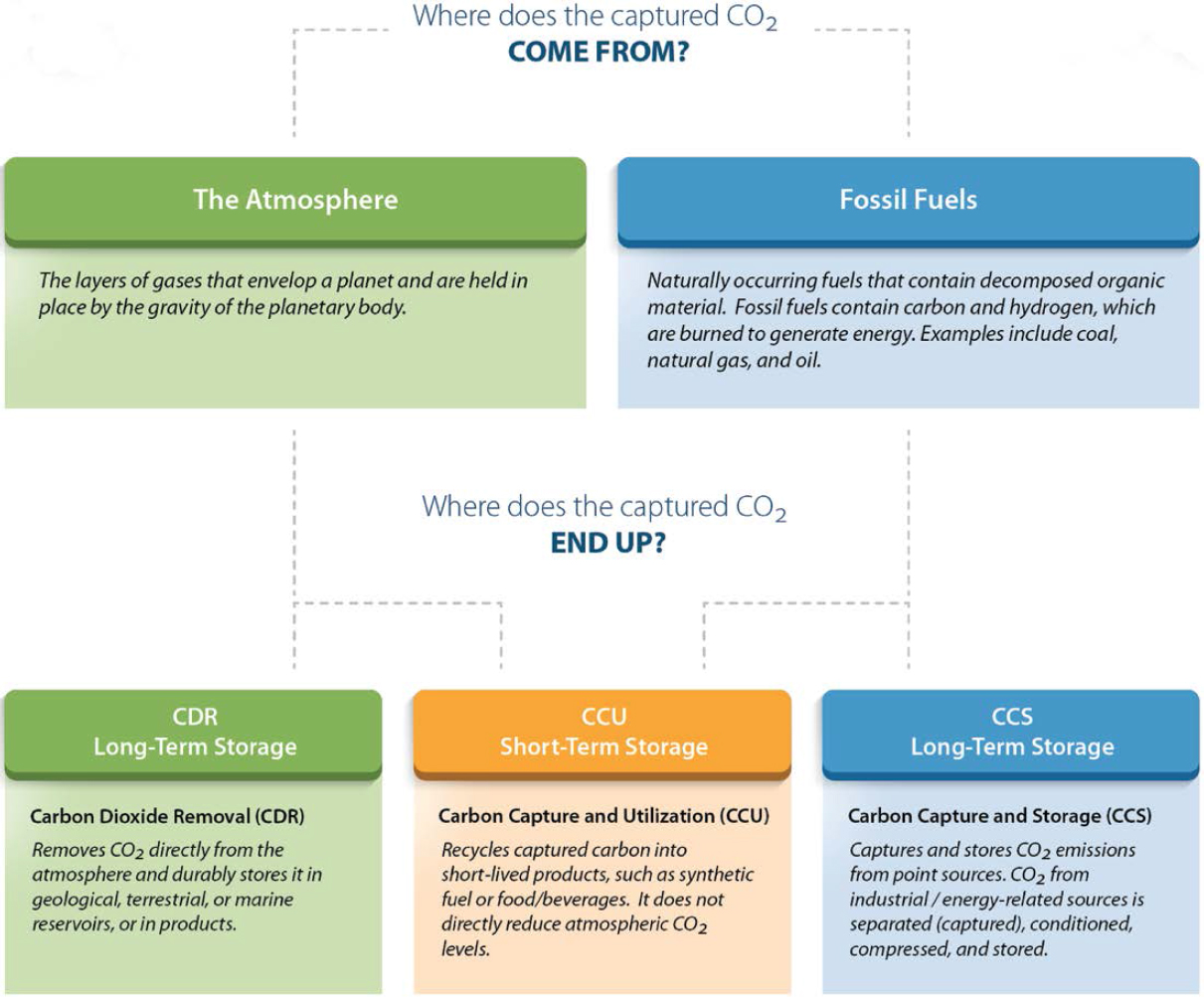

For the purposes of this guide and net-zero plans in general, it is critical to differentiate between CDR and carbon capture. Where CDR pulls directly from the atmosphere, carbon-capture techniques take carbon from an existing process (Figure 6). Explained differently, carbon capture focuses on newly produced CO2 (such as point capture off an industrial process), while CDR removes already existing CO2 or nonstationary CO2 that is hard to capture from the atmosphere (such as a DAC or land-use technique). Hence, CDR techniques eliminate atmospheric carbon, while capture techniques merely prevent additional carbon from entering the atmosphere. For CDR and carbon-capture techniques, it is also important to focus on the differences in durability or permanence. Carbon capture and utilization (CCU) secures and uses the CO2 for additional processes, such as the creation of biofuels, which means that CO2 is ultimately released back into the atmosphere (through the combustion process). Carbon capture and storage (CCS) involves capturing CO2 emissions from point sources (such as industrial smokestacks) and then storing the emissions (e.g., embedding captured emissions from a point source into concrete or other sequestration options). Figure 7 shows how CDR and carbon-capture methods (CCS and CCU) can be used to remove and store carbon.

As mentioned, this guide focuses primarily on CDR. However, additional research and case studies are needed to evaluate the benefits of CDR versus CCU [like DAC paired with another process, for example, the production of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), thus making it a CCU technique]. Likewise, point-source carbon capture is not a focus of this report but could be considered in future research relative to applications with other airport activities (such as point-source carbon capture and sequestration in pavements).

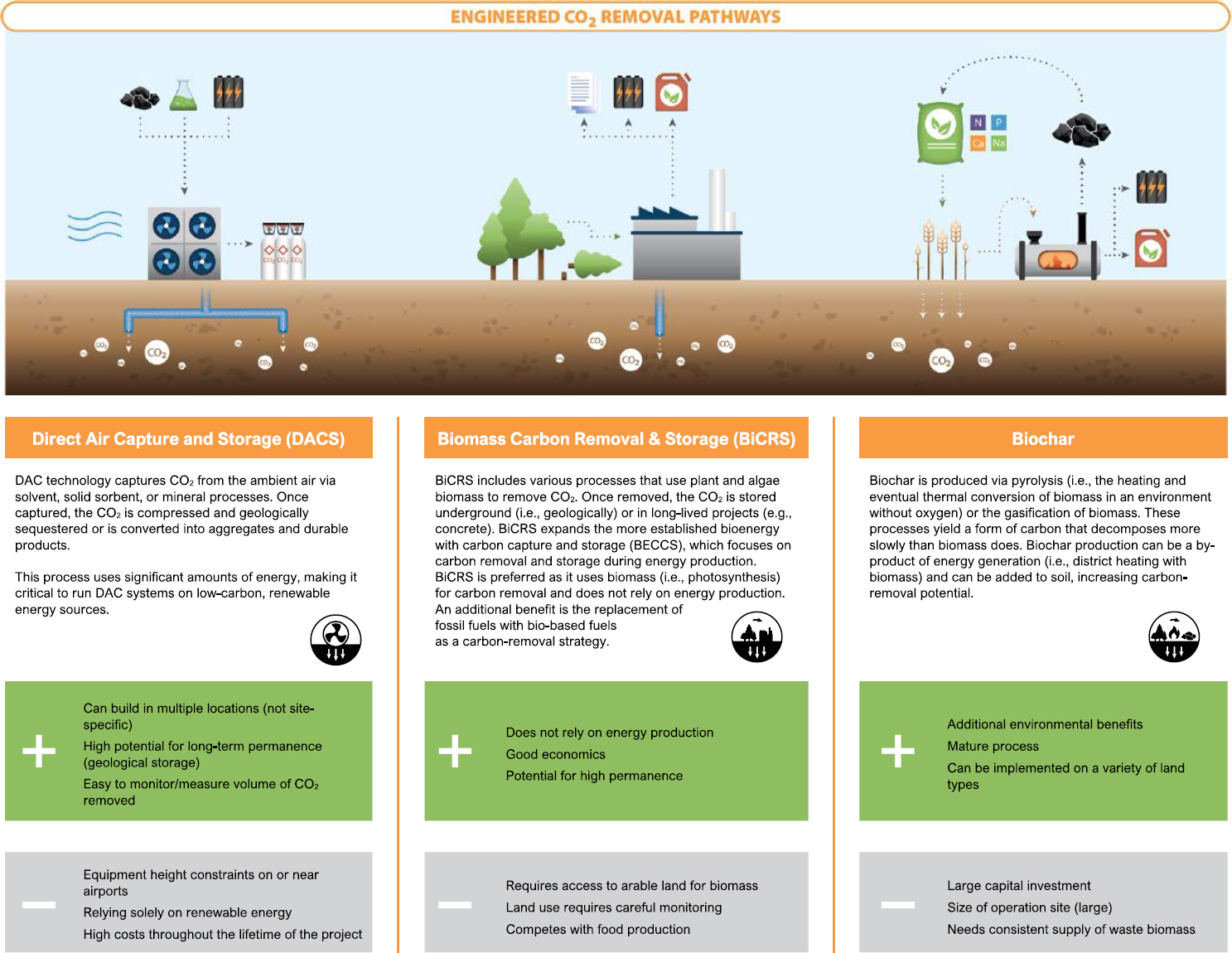

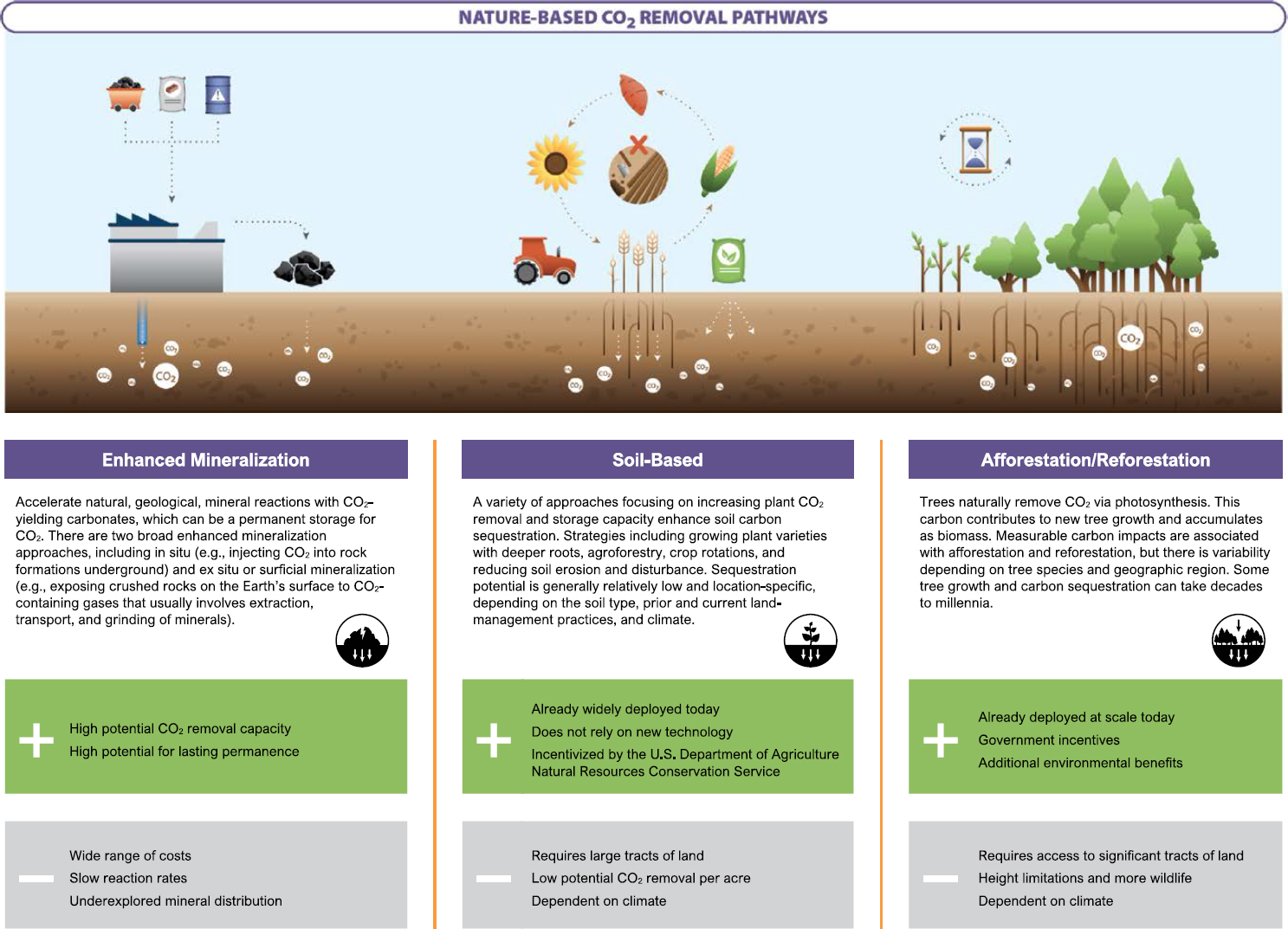

1.1.3 Types of CDR

CDR techniques fall primarily into three categories:

- Nature-based—Nature-based carbon removal refers to the naturally occurring carbon cycle. Many ecosystems act as carbon sinks by absorbing and storing atmospheric carbon. Types include afforestation and reforestation.

Figure 6. Carbon capture versus carbon removal.

- Technology-based—Technology-based carbon removal refers to engineered systems that remove atmospheric carbon. Examples include DAC.

- Hybrid—A combination of nature-based and engineered carbon-removal solutions. Examples include biomass carbon removal and storage (BiCRS).

CDR pathways that are currently most prominent include the following:

- BiCRS: This hybrid pathway uses plants and algae to remove CO2, then processes the biomass and stores it underground (i.e., geologically) or in projects with long lives (e.g., concrete). BiCRS expands the more established bioenergy with CCS (BECCS), which removes carbon during bioenergy production.

- DAC and storage (DACS): This engineered pathway captures CO2 from the ambient air via solvent, solid sorbent, or mineral processes. Once the CO2 is removed from the atmosphere, it is compressed and geologically sequestered or is converted into aggregates and long-lived products.

- Enhanced mineralization: This is a hybrid pathway that accelerates natural, geological, and mineral reactions with CO2, which yields carbonates (where the CO2 is then stored). Two broad enhanced mineralization approaches include in situ (e.g., injecting CO2 into rock formations underground) and ex situ, or surficial mineralization (e.g., exposing crushed rocks on the Earth’s surface to CO2-containing gases, which usually involves extraction, transport, and grinding of minerals).

- Soil-based: This nature-based pathway enhances soil carbon-sequestration potential by increasing plant CO2 removal and storage of carbon in soil. Strategies include growing plant

- varieties with deeper roots, agroforestry, crop rotations, and reducing soil erosion and disturbance.

- Afforestation/reforestation: This nature-based pathway relies on trees’ natural process of removing CO2 via photosynthesis. Trees store carbon in their biomass; the volume depends on tree species and geographic region.

- Biochar: This hybrid pathway produces biochar via pyrolysis (i.e., the heating and eventual thermal conversion of biomass in an environment without oxygen) or the gasification of biomass. These processes yield a form of carbon that decomposes more slowly than biomass does. Biochar production can be a by-product of energy generation (i.e., district heating with biomass) and can be added to soil, increasing the potential of soil to remove carbon.

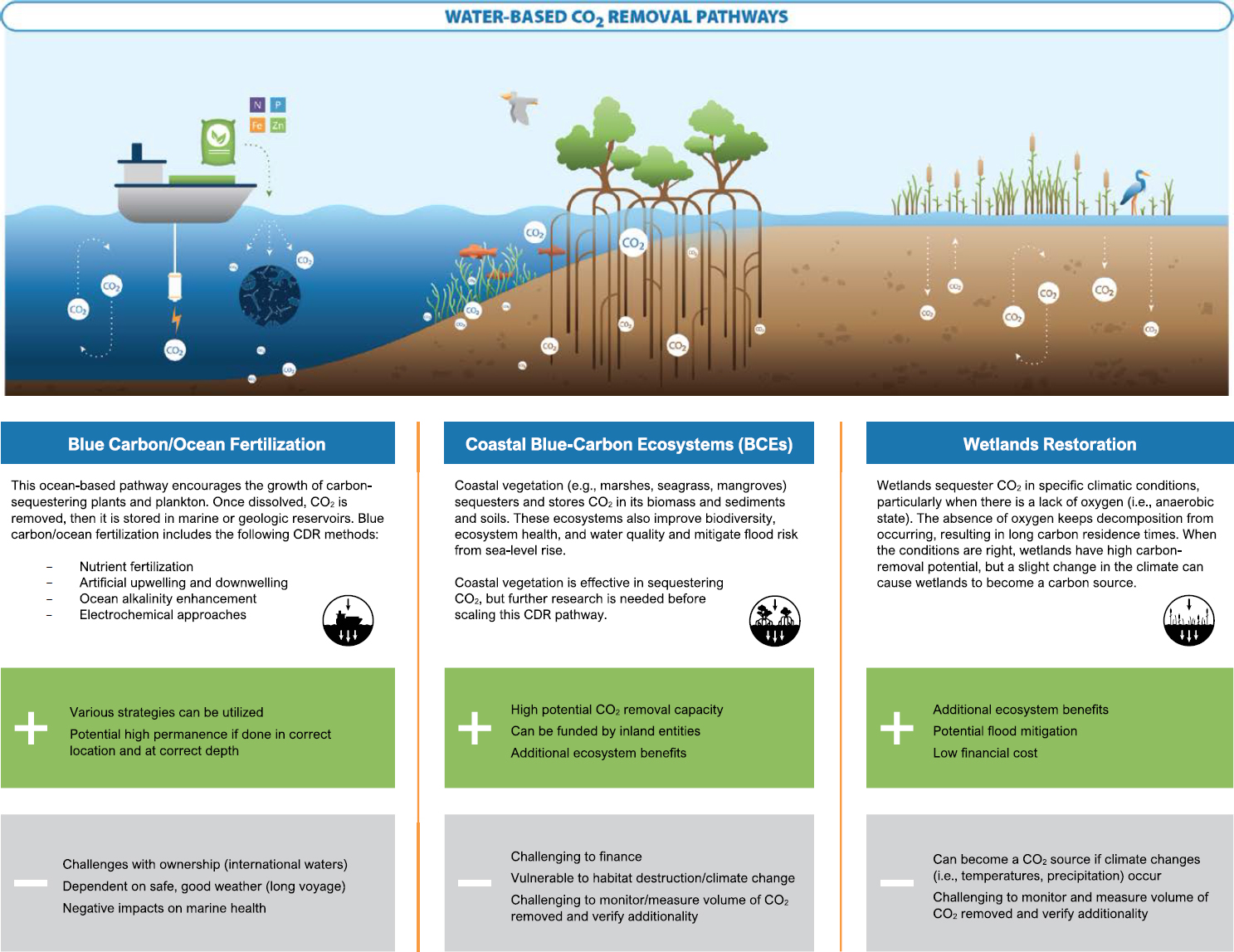

- Wetland: This is a nature-based pathway in which wetland restoration increases the CO2 that a wetland removes and stores. Wetland carbon has long residence times due to anaerobic conditions.

- Coastal blue-carbon ecosystems (BCEs): This nature-based pathway enhances marsh, seagrass, and mangrove CO2 sequestration and storage potential. Coastal plants store CO2 in the sediment, soil, and biomass.

- Ocean-based: This nature-based pathway encourages the growth of carbon-sequestering aquatic plants and plankton. Dissolved CO2 in the ocean is removed and then stored in marine or geologic reservoirs.

Figure 8 depicts the CDR approaches and technologies that will be discussed in following chapters of this guide. Each CDR approach has its own rate of CO2 uptake, land-use and energy requirements, durability, infrastructure needs, and costs.

All CDR approaches should be evaluated based on their associated CO2 removal potential, durability, volume and costs, and potential to cause additional harm (e.g., water or social costs). Ensuring CDR is net-negative (removes more emissions than are emitted during the process) requires a life-cycle assessment (LCA) that accounts for all CO2 and other GHG exchanges associated with the process, as well as other environmental and social impacts. For example, DAC may not necessarily achieve net negativity if the energy used to run the process releases more emissions than what is captured and stored, highlighting the importance of renewable energy in its use. Additionally, the durability of carbon removal varies across all CDR approaches, as carbon can be incorporated into biomass for a relatively short timescale, chemically transformed, or injected into geologic formations for hundreds or thousands of years of storage.

1.1.4 Types of Aviation Emissions

To address climate change, there is an opportunity for aviation industry leaders to emerge on a global scale and pioneer new best practices. As is evidenced in FAA’s and ACI World’s goal of achieving net-zero aviation emissions by 2050, the global aviation community is aligning with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to make the best effort possible to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (°C) relative to preindustrial levels, though broadscale changes are required to meet this goal. In 2018, total global aviation emissions, including fuel consumption of domestic and international flights, accounted for approximately 2.4 percent of total CO2 emissions [or 900 million tonnes (Tonnes and tons are both referenced throughout the report, depending on the information source. A ton is an imperial unit of mass equivalent to 1,016.047 kg or 2,240 lb. A tonne is a metric unit of mass equivalent to 1,000 kg or 2,204.6 lb)] (Graver, Zhang, and Rutherford 2019). The following year, 2019, recorded over 1,000 million tonnes of CO2 emitted from the aviation industry [International Energy Agency (IEA) 2022a]. Following COVID-19, 2021 emissions were approximately 720 million tonnes of CO2. This decrease is attributed to reduced travel due to travel restrictions associated with the pandemic (IEA 2022a). Operations have rebounded quickly following this reduction. The IEA expects emissions to increase at an average rate of 2.3 percent per year, aligning with historic trends from 1990 to 2019 (IEA 2022a).

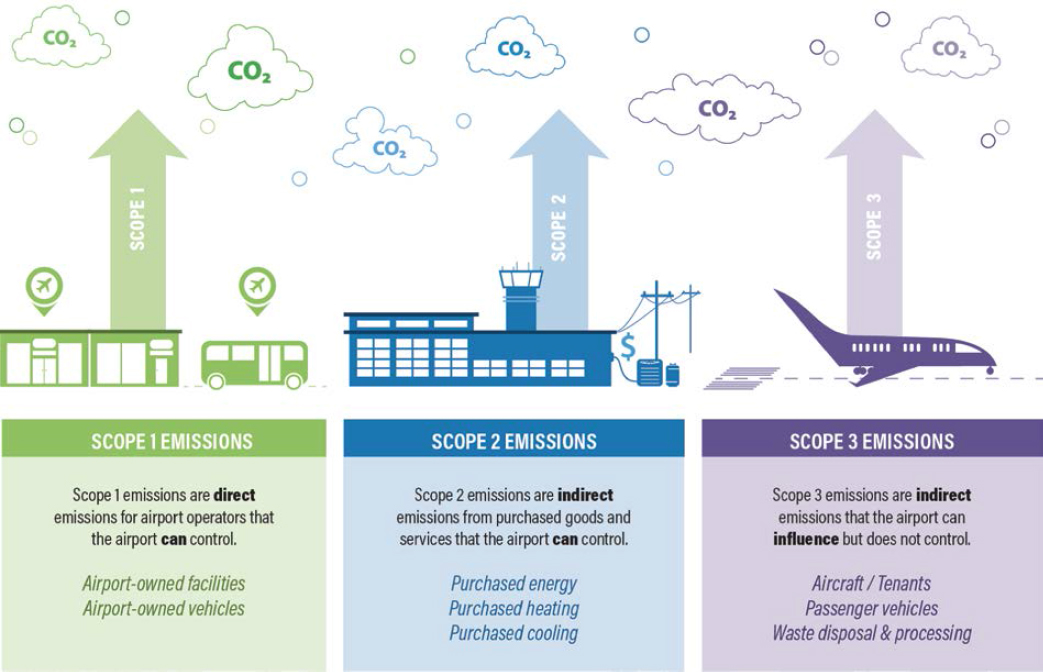

When discussing fuel emissions in the aviation industry, it is critical to first acknowledge typical GHG emissions inventory categories (or scopes) that are applicable to airports. These include Scopes 1, 2, and 3 emissions, which are defined in Table 3, and are based on the level of control an airport has in reducing emissions. Although fuel combustion from aircraft may be the most apparent source of emissions (Scope 3) in the aviation industry, airports specifically have significant emissions from their buildings and operations (Scopes 1 and 2).

This ACRP guide is focused on assisting airport operators in making progress toward net zero, which typically focuses on Scopes 1 and 2 (those emissions within an airport’s control). However, because of the sheer volume of Scope 3 emissions, and the fact that carbon removal can help with these hard-to-address emissions, CDR is likely to have a role in addressing all scopes of emissions across the industry.

Table 3. Airport GHG scope emissions per ACA.

| Category | Type of Emissions |

|---|---|

| Scope 1 | All direct emissions |

| Scope 2 | All indirect emissions (e.g., steam, purchased energy) |

| Scope 3 | Other indirect emissions (e.g., outsourced activities, transportation in vehicles that are not owned by the airport, aircraft emissions) |

Source: https://www.airportcarbonaccreditation.org/about/7-levels-of-accreditation/.

1.1.5 Aviation Industry—International Organization Goals

To address aviation-related emissions, international aviation institutions and organizations, including the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the International Air Transport Association (IATA), are focusing on achieving net zero by 2050 through reduction and other measures to achieve climate targets (previously shown in Table 2).

ICAO has set a goal of improving fuel efficiency by 2 percent annually through 2050 and deploying new technologies to reach net zero. The IATA reductions target assumes that 81 percent of emissions will be abated through SAF, technology advancements, and operational measures; the remaining 19 percent will need to be addressed through offsets/carbon-removal techniques (IATA 2021).

1.1.6 Aviation Industry—Goals

Industry Alignment

Global and national aviation organizations have coalesced under the goal for net zero by 2050 for the aviation industry. As is evidenced in the ACI Long-Term Carbon Goal Study for Airports (ACI 2021), FAA’s Climate Action Plan (FAA 2021), and ICAO and IATA targets, there is consensus that to fully achieve decarbonization by 2050, aviation stakeholders will need to focus on reduction and efficiency measures and employ new technologies; CDRs will be a necessary component. Two of the primary net-zero goals are described in following sections.

ACI World and North America

ACI, comprising members from 1,925 airports in 171 countries, has committed to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050; aligning with the IPCC’s goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. As previously mentioned, carbon dioxide is only one of many harmful GHGs; rather than trying to curb all GHG emissions, ACI solely focuses on carbon dioxide as it is the main contributor of GHG emissions by airports. Further, airports are not required to contribute to ACI’s net-zero 2050 goal but can do so voluntarily. “It is important to note that net zero for airports, as described in the ACI net zero goal, is net zero emissions from Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions for airports, those emissions that they own or have control over” (ACI 2021). On average, Scope 3 emissions (primarily aircraft operations) typically comprise over 90 percent of an airport’s GHG emissions.

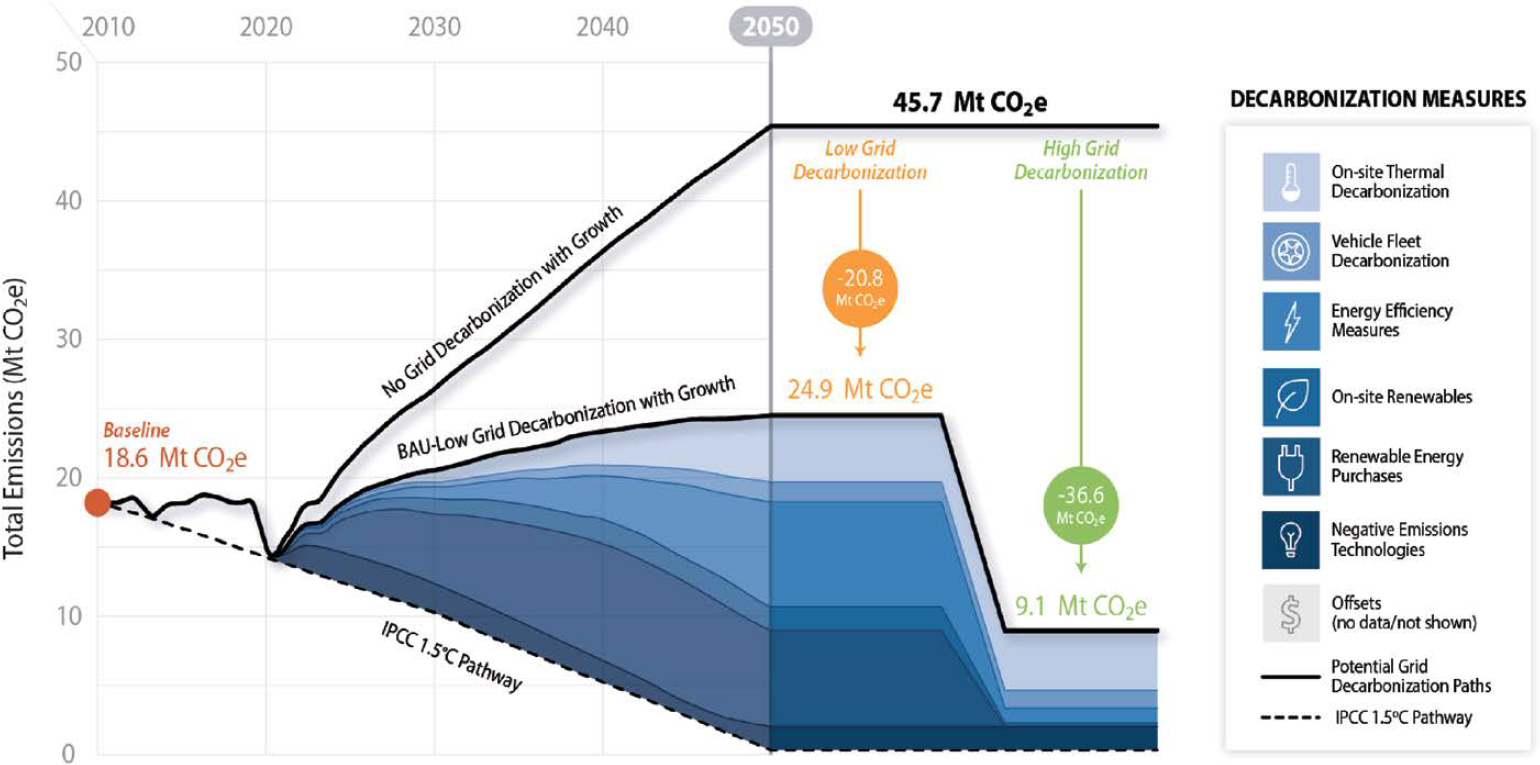

ACI’s Long-Term Carbon Goal Study for Airports (2021) defines net-zero carbon as reducing emissions as much as possible and using carbon removal (not offsets) to account for the residual emissions. The roadmap provided by ACI includes decarbonization measures and acknowledges the need for offsets in the short term and negative emissions (or CDR) as shown on the graph in Figure 9. The Long-Term Carbon Goal Study notes that CDR [referenced as negative-emissions

Figure 9. Global emissions-reduction pathways (Mt-CO2e = metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent; BAU = business as usual).

technologies (NETs)] are needed to achieve net zero, and that purchasing offsets through a third party is not a substitute for direct carbon-removal measures by the airport.

If an airport has reduced its emissions as much as reasonably and feasibly practicable, the only emissions left are the most challenging to decarbonise. To achieve Net Zero Carbon emissions, airports will also need to deploy appropriate negative emissions technologies, nature-based or direct air capture carbon storage (DACCS), alongside other emissions reduction measures to directly remove all residual carbon. There are various means to remove carbon from the atmosphere, mostly still at early development stages. Specific technologies and related airport applications should be considered as they become available. . . . Carbon offset schemes provide a mechanism for airports to initially compensate or neutralise carbon emissions through financing projects that absorb or reduce carbon emissions. However, they do not provide a substitute for direct carbon removal measures which will be required to achieve Net Zero Carbon emissions by 2050.

(ACI 2021)

FAA Goals

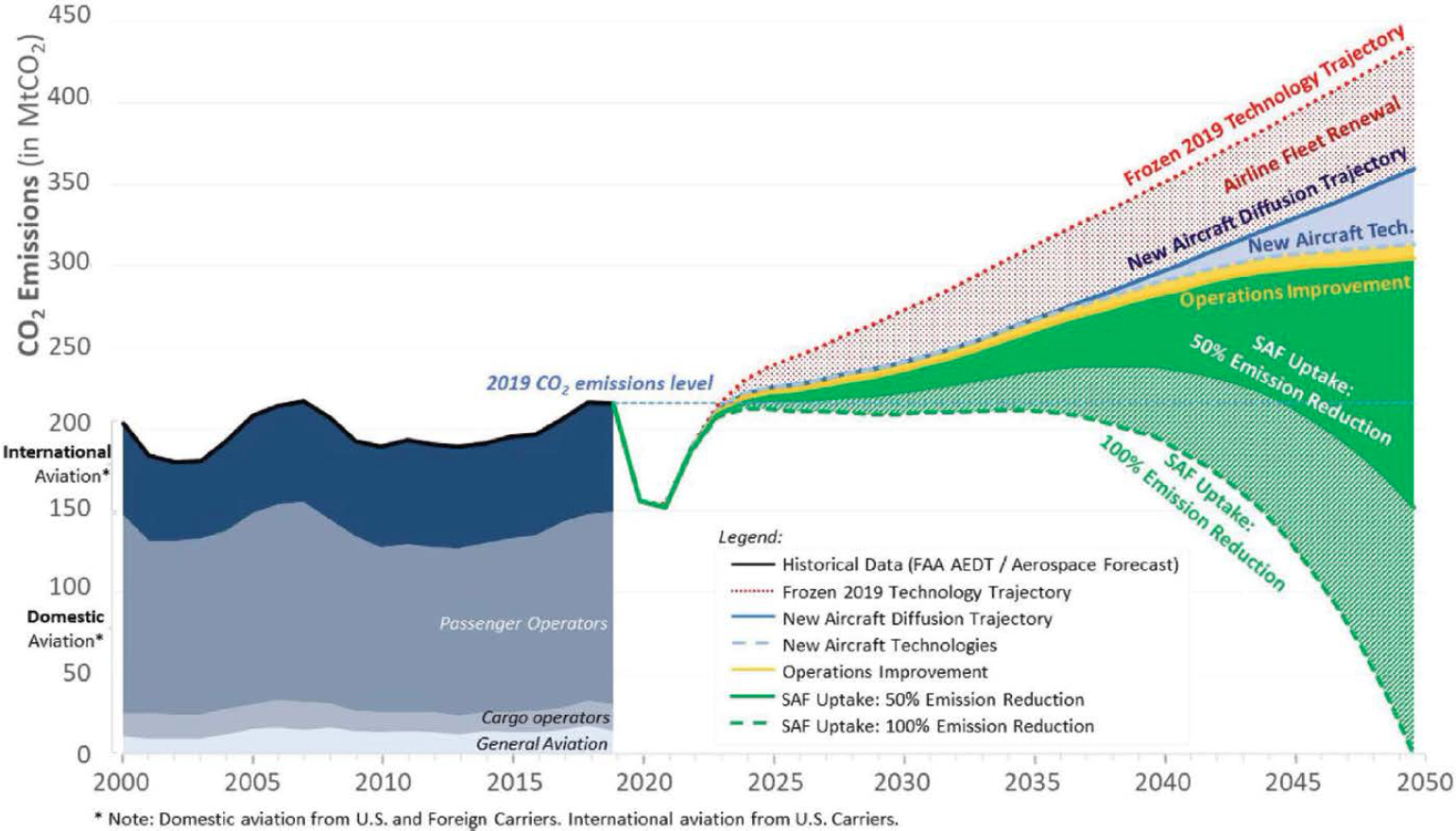

In the United States, the FAA has established a decarbonization roadmap for the aviation sector. The FAA Aviation Climate Action Plan goal is to achieve net-zero GHG emissions from the U.S. aviation sector by 2050. Unlike the ACI goal, the FAA goal includes all GHG emissions, including CO2, nitrous oxide (N2O), and methane (CH4).

This FAA goal encompasses CO2 emissions from the following:

- Domestic aviation (i.e., flights departing and arriving within the United States and its territories) from U.S. and foreign operators

- International aviation (i.e., flights between two different ICAO member states) from U.S. operators

- Airports located in the United States

Figure 10 includes a breakdown of technologies and operational improvements that must be implemented to reach this goal. The FAA expects most emission reductions to come from SAF innovations.

1.2 Airports Net-Zero Roadmaps

As illustrated previously, to establish a path forward in achieving net-zero emissions by 2050, airports are now developing net-zero roadmaps to meet the 2050 target (or, in some cases, earlier targets). The goal of a roadmap is to create an actionable strategy that will lead directly to implementing measures to reduce and ultimately eliminate carbon emissions associated with the airport. CDR will be a necessary component for airports to bridge the gap from reduction methods (i.e., energy efficiency measures, electrification, and on-site renewable energy) to reach net zero.

CDR Integrated in Net-Zero Roadmaps

CDR methods can be used to address all categories of emissions at an airport because it results in CO2 removal directly from the atmosphere. However, CDR at this time is not a replacement for reductions, and to achieve net zero under ACA Level 5, no more than 10 percent of the emissions (Scopes 1 and 2) should be targeted through CDR.

One of the primary challenges with decarbonizing airports specifically is that there are large sources of emissions (primarily aircraft) associated with an airport that fall outside the control of an airport. The ACI ACA follows the Greenhouse Gas Protocol definition for Scopes 1, 2, and 3 emissions, as illustrated in Figure 11 (ACI 2023). Scope 1 refers to all direct GHG emissions that occur from sources owned or controlled by the company, in this case an airport. Scope 2 accounts for indirect GHG emissions from the generation of purchased electricity consumed by an airport. Most airport-controlled emissions are typically Scope 2, or those related to the generation of off-site electricity.

Figure 10. FAA analysis of future domestic and international aviation CO2 emissions (AEDT = Aviation Environmental Design Tool).

According to ACI, the 2010 baseline of Scopes 1 and 2 emissions for airports was established at 18.6 metric tons (Mt) of CO2, with 10.3 percent of emissions attributed to Scope 1 sources and 89.7 percent of emissions from Scope 2 sources (ACI 2021). Scope 3 is an optional reporting category in the ACA for Levels 1 and 2 but is required at and above Level 3, as noted in the following section. Scope 3 includes other indirect GHG emissions, such as aircraft emissions, which are by far the largest source of emissions in the aviation industry.

As a reminder, the ACI net-zero goal is focused on Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions due to an airport’s ability to control and influence these emissions. However, aircraft and other Scope 3 emissions are included under the goals of the FAA, the IATA, and the ICAO, to capture the broader industrywide impact of the aviation industry. Airports in recent years have been working collaboratively with airlines and other stakeholders to look for innovative ways to address aircraft emissions. An airport’s net-zero roadmap will differ based on the individual airport’s definition of net zero (i.e., which scopes of emissions are included). This report focuses on CDR methods for airports to get to net zero; however, these CDR methods can be used to address all categories of emissions because the methods result in CDR directly from the atmosphere.

Most airports that have committed to reducing emissions have developed GHG inventories to establish baseline conditions and regularly update these inventories to track progress toward emissions reductions. This exercise allows an airport to (1) track progress associated with existing emissions-reduction measures, (2) identify areas in need of improvement, and (3) provide data to project future emissions for developing a successful net-zero roadmap within the context of forecasted growth at an airport.

There are currently two airport-specific methodologies for inventorying airport emissions: the ACI ACA methodology and the ACRP method outlined in ACRP Report 11: Guidebook on

Preparing Airport Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventories (Kim et al. 2009), which is currently undergoing updates. ACRP Report 11 is only an inventory methodology, while ACA provides a methodology for quantifying emissions and a certification process for achieving progress toward GHG emissions goals. Both methodologies are summarized in the following sections, which also include the context of how CDR fits within the certification process.

1.2.1 ACI ACA

In 2009, ACI Europe launched ACA, the only institutionally endorsed global carbon-management certification program for airports (ACI Europe 2020). This program assesses and recognizes the efforts each airport is putting toward emissions reductions. There are currently seven levels of accreditation, with the highest being Level 5:

- Level 1: Mapping—Footprint measurement

- Level 2: Reduction—Everything required from Level 1, plus carbon management toward a reduced carbon footprint

- Level 3: Optimization—Everything required from Levels 1 and 2, plus third-party engagement in carbon footprint reduction

- Level 3+: Neutrality—Everything required at Levels 1, 2, and 3, plus offset of remaining airport-controlled emissions

- Level 4: Transformation—Everything required in Levels 1–3+, plus transforming airport operations and business partners to achieve absolute emissions reductions

- Level 4+: Transition—Everything required in Levels 1–4, plus offsetting residual carbon emissions over which the airport has control

- Level 5: Currently the top level, focused on net-zero balance on Scopes 1 and 2, with offsets for residual emissions.

ACA Level 5 was developed as a higher level for airports to claim net zero. Any residual emissions would need to be addressed using NETs, a term used in the ACA Level 5 guidance that is similar to CDR and is separate from traditional offsets. As a part of Level 5, 90 percent of emissions must be met through reductions, and the remaining 10 percent residuals can be offset with carbon-removal offsets.

TERMINOLOGY

Negative-Emissions Technologies (NETs) Versus Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR)

While NETs represent methods for carbon removal, this guide refers to carbon-removal pathways as CDR because this terminology captures a broader group of carbon-removal pathways. The term “NET” generally refers to a technological approach; however, in the existing guidance, ACI is including land-use, hybrid, and technological approaches that are approved as a carbon-removal offset.

Furthermore, for Level 5, NETs would need to meet requirements for additionality and permanence (over 100 years) and must be controlled by the airport operator. This is important because some of the carbon-removal technologies in this guide may not meet the requirements for NETs, as defined by ACA Level 5. Therefore, airports that are looking for net-zero certification through the ACA program will need to evaluate whether the methods they are considering align with the requirements of the program.

A future Level 6 is also being developed for the ACA program, which will certify an airport to be climate positive (meaning the airport removes more carbon from the atmosphere than it produces). While Level 5 addresses residual emissions, Level 6 (yet to be released) will begin to address legacy emissions. Therefore, carbon removal (directly from the atmosphere) will be a required component of ACA Level 6.

1.2.2 ACRP Report 11: Guidebook on Preparing Airport Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventories

ACRP Report 11: Guidebook on Preparing Airport Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventories (Kim et al. 2009), provides a framework for developing GHG inventories. Unlike ACA, this

methodology does not incorporate certification of the results. ACRP Report 11 is currently being updated under a separate ACRP project.

This inventory methodology is often used by airports that may not be members of ACI and are not looking for certification but rather to simply document their emissions and create their own emissions-related roadmaps separate from the certification process. Reasons that airports may use the ACRP methodology rather than that of the ACA include the costs of ACA certification or that airports are focused on partnerships and alignment with broader city, county, or regional net-zero plans that might be certified under other protocols. However, this methodology does not provide certification for net-zero goals.

1.3 Links to Previous ACRP Research

The previous sections provided a summary of pertinent research and context on global climate change, net-zero goals in the aviation industry, as well as the role of CDR to address residual emissions (remaining GHG emissions after a project or organization has implemented all technically and economically feasible opportunities) and legacy emissions (long-lived emissions). Building on that research, the research team also reviewed past ACRP research related to climate and carbon emissions to identify gaps in the research and, specifically, identify why research on CDR is needed. Previous ACRP research has been largely focused on energy reduction, renewable energy, and other climate-mitigation topics.

ACRP has published many valuable resources and guides to educate and support airports on climate-related topics. A more comprehensive discussion of the literature review is found in Appendix C. The following reports most align with the research for this project and are summarized in Table 4:

- Accounting for emissions

- ACRP Report 11: Guidebook on Preparing Airport Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventories (Kim et al. 2009)

- Track and reduce

- ACRP Report 56: Handbook for Considering Practical Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction Strategies for Airports (CDM and Synergy Consultants, Inc. 2011) (includes the Airport-GEAR tool for reductions strategies for Scopes 1, 2, and 3)

- ACRP Research Report 220: Guidebook for Developing a Zero- or Low-Emissions Roadmap at Airports (Morrison et al. 2021)

- ACRP Synthesis 100: Airport Greenhouse Gas Reduction Efforts: A Synthesis of Airport Practice (Barrett 2019)

- ACRP Synthesis 110: Airport Renewable Energy Projects Inventory and Case Examples: A Synthesis of Airport Practice (Barrett 2020)

- Carbon-market opportunities

- ACRP Report 57: The Carbon Market: A Primer for Airports (Ritter, Bertelsen, and Haseman 2011)

The existing ACRP reports provide valuable insights and recommendations regarding targeting low emissions, GHG reductions, the carbon markets, and other climate-mitigation topics. However, ACRP Report 56 is the only published material that mentions carbon-sequestration strategies to capture and store atmospheric carbon. ACRP Report 56 includes a high-level explanation of CDR and explains CDR feasibility based on the following screening criteria: location; durability and permanence; and monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV).

Many of the CDR technologies presented in ACRP Report 56 can be applied to Scopes 1, 2, and 3 emissions. The report addresses the importance of setting a net-zero goal and for airports

Table 4. Related ACRP research.

| Resource Title | Primary Focus | Summary | Overlap with ACRP Project 02-100, “Carbon Removal and Reduction to Support Airport Net-Zero Goals” |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accounting for Emissions | |||

| ACRP Report 11: Guidebook on Preparing Airport Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventories (Kim et al. 2009) | Identifying and quantifying airport-specific GHG emissions sources to compile an inventory | Provides framework for identifying and quantifying airport emissions, as well as developing a GHG inventory Provides calculation methods and instructions on how to calculate emissions from a specific source |

|

| Track and Reduce | |||

| ACRP Research Report 220: Guidebook for Developing a Zero- or Low-Emissions Roadmap at Airports (Morrison et al. 2021) | Developing zero- and low-emissions strategies | Shares a roadmap to pursue strategies that reduce or eliminate GHGs |

|

| ACRP Report 56: Handbook for Considering Practical Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction Strategies for Airports (CDM and Synergy Consultants, Inc. 2011) | Exploring GHG reduction opportunities for daily operations and for those associated with specific projects | Offers a breakdown of emissions-reduction strategies and the associated capital investment/cost and payback period Discusses AirportGEAR tool |

|

| ACRP Synthesis 100: Airport Greenhouse Gas Reduction Efforts: A Synthesis of Airport Practice (Barrett 2019) | Examining GHG reduction | Explores the status of GHG reduction efforts following the release of ACRP Report 56 |

|

| ACRP Synthesis 110: Airport Renewable Energy Projects Inventory and Case Examples (Barrett 2020) | Reviewing renewable energy at airports | Summarizes renewable energy projects at airports across the United States |

|

| Carbon-Market Opportunities | |||

| ACRP Report 57: The Carbon Market: A Primer for Airports (Ritter, Bertelsen, and Haseman 2011) | Looking at carbon markets—opportunities for airports | Explores whether there are revenue opportunities generated by selling credits on the carbon market; examines opportunities for airports earning credits via renewable energy credits |

Challenges with carbon-offset projects for airports due to

|

to explicitly disclose which scopes are included in the reductions target. ACRP Report 57 discusses the link of carbon sequestration (through afforestation and man-made solutions) and the carbon market. The report focuses on the structure of the carbon market and how airports can work within the carbon market with developers to create offsets to sell on the open market. However, CDR techniques and applicability for airports are not discussed in detail.

Much of the previous research reported by ACRP has focused on emissions-reduction strategies; CDR was referenced only in ACRP Report 56 and ACRP Report 57. However, emissions-reduction measures will leave residual and legacy emissions to address. Therefore, this report builds on previous research findings to focus on a better understanding of CDR techniques, the link between CDR techniques and net-zero planning, and the applicability of employing CDR techniques specifically at airports.

1.4 Context of Carbon Markets and CDR Certifications

1.4.1 Overview

Carbon markets are used to trade and deliver climate benefits from one entity to another. Most carbon offsets available today are related to emissions avoidance or reductions, and although necessary and beneficial, they are not sufficient to achieve global science-based targets to limit temperatures to 1.5°C by 2050. A purchaser obtains a carbon offset for the value of 1 ton of CO2 that will be avoided or reduced somewhere else, to compensate for the same ton that the purchaser will emit. Carbon credits and offsets can be purchased, or used, by an individual or a company to either remove or reduce emissions. Although participation in carbon markets is one option for addressing climate change, it cannot be the only strategy an organization implements to reach net zero. Carbon markets should be used to manage emissions that cannot be reduced or are unavoidable, and they should not be the first, or even second, step in carbon-reduction efforts.

Could Airports Sell Carbon-Removal Offsets?

Based on current research, on-site airport projects would be nature-based CDR. It is very unlikely that an airport would have leftover credits or offsets to sell from a land-use project. On the other hand, technological CDR will likely be owned by a project developer, and an airport will have ownership rights via a lease or purchase agreement, but it is unlikely that they will have the direct rights to sell credits or offsets from the project.

Carbon markets are expected to grow significantly over the next 100 years, organically and through agreements and regulations. Article 6 of the Conference of the Parties (COP) 26 (the United Nations Climate Conference) allows different countries to transfer carbon credits and offsets with each other to attain their nationally determined contributions (NDCs), but the amount of offsets are limited (IPCC 2023b; The World Bank 2022). Under this provision, each government is involved in the approval and trading process. Today, there are two predominant carbon-market types: the CCM and the VCM. Governments use the CCM, which is generally larger and more developed than the VCM, to achieve their carbon-reduction targets, while the VCM provides organizations and companies with a way to offset their carbon emissions on a voluntary basis. Both carbon markets are actively maturing and scaling. CCMs are present in only some countries and for some industries, making the VCM a more universal option for reducing or removing unavoidable emissions. To date, the California Global Warming Solutions Act, European Union’s Emissions Trading System, and the Chinese National Emission Trading System are the predominant CCMs. However, offsets and credits have received increasing scrutiny over the past few years in providing the carbon-reduction or removal benefits and the accounting behind it.

1.4.2 Terminology—Carbon Credits and Offsets

Through the research conducted for this project, carbon markets were highlighted as a challenge. Terminology around carbon offsets and credits can be confusing and inconsistent, and made

more confusing in the context of some net-zero goals where offsets are not allowed. Currently, the carbon-market space often interchangeably uses the terms carbon offsets and carbon credits. In some definitions, carbon credits are sometimes aligned with reduction measures and carbon offsets that involve carbon removal. Use of different definitions is inconsistent and sometimes also dependent on whether they are used in the context of the CCM or the VCM, as described in more detail in following sections. Where there is a difference in definitions, the definitions sometimes contradict each other or are used in different contexts.

When discussing the carbon markets, a clear understanding of the differences between carbon credits and carbon offsets is critical, as some aviation net-zero goals have a distinction on meeting the goal without traditional offsets. The distinction used in this guide is described in Table 5.

Based on the definitions in Table 5, the guide will use “carbon offset” as the correct term for any project in the VCM. Because airports are currently not under compliance requirements, offset is the correct term. However, there is additional confusion in this area because carbon offsets are also not distinguished in type between removal and avoidance. As stated previously, some of the aviation climate goals indicate net-zero alignment must be without offsets.

Microsoft, in collaboration with Carbon Direct, published a “Criteria for high quality carbon removal” (Microsoft 2021), and in March of 2022, they published lessons learned from carbon removal. The first challenge listed was that the “market lacks strong, common definitions and standards” (Microsoft 2022). Offsets and credits are often lumped together, and the mechanism for providing the GHG benefits is often not separated by carbon removal (directly from the atmosphere) versus carbon reduction (avoided or reduced emissions). The report states, “Removals are not consistently distinguished from offsets that cover avoided or reduced emissions, particularly in the most widely used standards” (Microsoft 2022).

This confusion noted by Microsoft is very applicable to airports because ACI’s goal for net zero includes the use of no traditional carbon offsets, which can be misleading in that it is difficult to separate a purchased offset from an emissions-avoidance project versus full removal that may or may not be owned by the airport (in either case, this would need to be certified by an offset organization to prove that the project removed the GHGs in a verified procedure). ACA has provided guidance on approved carbon-offset projects that help make this distinction.

Because of the lack of consistent terminology around the carbon market and integration with CDR, this report will use the term “carbon-removal offset” to avoid confusion between

Table 5. Comparison of carbon credit and carbon offset.

| Comparison Question | Carbon Credit | Carbon Offset |

|---|---|---|

| What Is a Credit Versus an Offset? | A permit for an owner to emit a certain amount (typically one metric ton) of GHG emissions | The removal or avoidance of a certain amount (typically one metric ton) of GHG emissions |

| Who Creates Them? | Issued to emitters by a regulatory body | Issued by organizations that certify and track GHG emissions reduction |

| Can They Be Traded? | Yes | Yes |

| Where Are They Traded? | Compliance market | Most likely in the voluntary market |

Source: Based on Ollendyke 2023.

carbon-offset projects from avoidance versus CDR pathways. The following sections go into more detail on the two types of carbon markets, followed by their applicability to airports. This distinction matters, because ownership and operation of carbon-removal projects may be difficult for airports, making it more likely that they will have to purchase carbon-removal offsets to meet a certifiable net-zero goal.

TERMINOLOGY

Carbon Offset Versus Carbon Credit

A carbon offset or credit is associated with one metric ton of CO2 removed or avoided and available, sold, or purchased in the carbon market.

Many people use carbon offset and carbon credit interchangeably. The term “carbon credit” is used for the CCM, and the term “offset” should be used for the VCM. For airports, since there is no current CCM, “carbon offset” is the proper term for the VCM.

There is additional differentiation between carbon-reduction and carbon-removal projects. Therefore, for this report, the term for a certified ton of removed carbon for a CDR project is “carbon-removal offset.”

1.4.3 The CCM

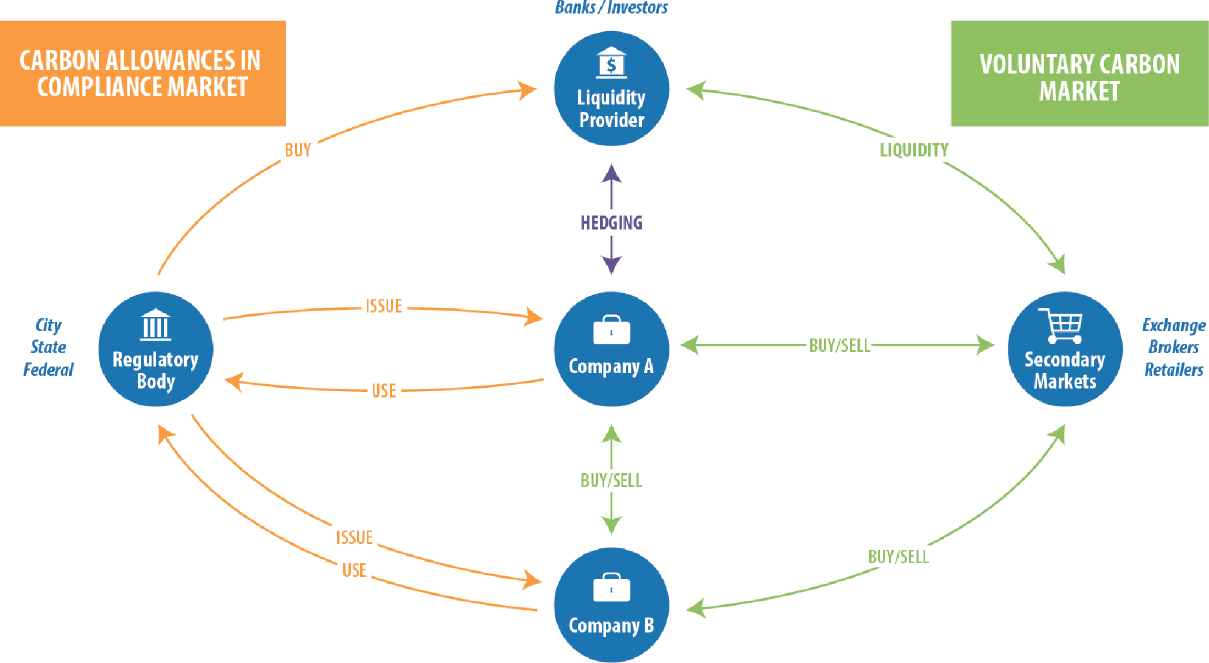

In the CCM [also known as the Emissions Trading System (ETS) or the cap-and-trade market], organizations comply with regional, national, or international regulatory requirements to meet reduction, removal, and neutrality goals. The carbon credits and offsets in the compliance market are priced based on government and regulatory policy, particularly in regard to setting a maximum amount of emissions allowed (CarbonCredits.com 2022). Once this threshold is set, a carbon emitter can buy more credits if they emit over a threshold or can sell credits they already own if they emit less than the regulatory limit.

There are approximately 30 ETSs globally within 38 jurisdictions [Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) 2022]. The three main CCMs are the European Union’s ETS, the California Global Warming Solutions Act (more commonly known as the California Cap-and-Trade Program), and the Chinese national emissions trading scheme (CarbonCredits.com 2022). In 2021 the CCM was valued at over $100 billion in U.S. dollars (USD) with annual trading turnover exceeding $250 billion USD (McKinsey Sustainability 2023). Figure 12 demonstrates the interactions, active entities, and trade flow of the CCM.

1.4.4 The VCM

In contrast to the CCM, the VCM is a market for entities and individuals to trade carbon offsets voluntarily (McKinsey Sustainability 2023). The VCM is unregulated, but it allows companies to purchase carbon offsets that are certified by private standards and are often bought directly from project developers (MSCI 2022). Due to its voluntary nature, the VCM plays a significant role in driving and allocating capital into carbon-reduction projects and carbon-removal projects. Although the CCM is larger and more mature as of now, the VCM has considerable potential to scale up in size. Due to the lack of government regulation and policy, the VCM is less constrained than its counterpart (S&P Global Commodity Insights, n.d.). The VCM price of carbon offsets is based on supply and demand, rather than policy. MSCI reports that the VCM is growing more slowly than the CCM due to a lack of supply in high-quality carbon offsets (MSCI 2022).

1.4.5 Insetting Versus Offsetting

“Insetting” is a relatively new term to the carbon-market and carbon-removal landscape, but it is expected to grow in popularity over the short term and has applicability to airports. Insetting projects typically focus on removing and curbing Scope 3 emissions. Ideally, Scopes 1 and 2 emissions will be managed first through operational changes, and CDR projects will tackle unavoidable residual emissions. Although there is no universally accepted definition yet, insetting generally refers to funding and implementing one’s own CDR project, having full ownership

Figure 12. CCM trading flow.

and control over it, and avoiding the VCM or CCM (Sylvera 2023). For example, rather than buying offsets from a forest project, the entity will grow its own forest (Sylvera 2023). Insetting projects are often conducted on-site or within local communities that are a part of an organization’s value chain (Sylvera 2023).

Insetting projects follow the same standards and criteria as traditional CDR offsets and credits in the VCM, but they traditionally take longer to develop and require more work. Also, insetting projects are less flexible than offsetting projects, but they ultimately allow the entity to have full ownership and understanding of the carbon-reduction and removal efforts. Purchasing offsets and credits is often criticized due to the lack of effort required and can be referred to as “a license to pollute” (Sylvera 2023). A benefit of insetting projects is that stakeholders (e.g., employees and the local community) can be more involved and understand the positive impact. As carbon-reduction and removal efforts become more commonplace, having this internal asset will become more valuable. Rather than relying on the carbon market and being affected by the price fluctuations, insetting projects will prove to be more beneficial in the long run. Table 6 compares insetting and offsetting in more detail.

The distinction between insetting and offsetting is important for airports because in some cases airports may want to have ownership over their own projects, but with land-use, leasing, operational, and other challenges, it may be difficult for airports to develop their own CDR project. Some nature-based pathways are more likely to be airport owned. However, at this point, it is more likely that an airport would need to work with a developer for any technological or hybrid pathway, due to the complexities and if there is desire to certify the project. To implement on-site CDR, or an insetting project, it is critical to first have a robust understanding of

Table 6. Comparison of insetting versus offsetting.

| Offsetting | Insetting |

|---|---|

| Less administration and legal work | More administrative legwork |

| Lower capital expenditure costs in the short term | Higher capital expenditure costs in the short term |

| Potentially higher costs in the long term | Lower operational expenditures in the long term |

| Easier to form a diverse portfolio of offsetting projects | Typically limited to a single project or a small number of projects |

| Higher risk exposure to changing credit supplies and prices | Security of credit supply and carbon pricing (credits available to your organization at cost) |

| Market selection only, often far removed from daily operations | Customized projects based on your organization; often local and relevant |

| Does not contribute to absolute emissions reductions | Contributes to emissions reductions |

| Offset quality can be measured with rigorous methodologies and next-gen MRV technology by independent third-party companies | Measuring inset quality can be more complicated and require in-house resources |

Source: Sylvera 2023.

current emissions. Before deploying a CDR project, the owner must execute a land-use analysis to determine the best project type and location. A third-party CDR expert will need to assist during this phase.

1.4.6 Approval and Certification

The carbon market currently relies on independent institutions to approve and validate the credibility of carbon offsets and credits. Approval processes often follow a specific set of protocols verifying the following:

- The project is additional and would not have happened without the sale of carbon offsets or credits.

- Overestimation has not occurred—ensure that the number of carbon offsets or credits match the amount the project can produce.

- The carbon offsets and credits are permanent (based on the project’s lifetime). The emissions removals or reductions cannot be reversed, and the carbon has been both removed and sequestered. The durability will vary depending on the project type; most common carbon offsets (natural) last for fewer than 100 years, while other technological methods have longer permanence.

- The carbon credits or offsets are not claimed or purchased by another entity. Carbon offsets and credits are retired after being purchased to avoid being double counted.

- The project is not associated with social or environmental harm (Broekhoff et al. 2019).

A best practice for carbon-credit and carbon-offset purchasing is to refer to a registry that verifies programs through independent third-party verification. It is critical to confirm that the project has correct accounting and baseline methods, permanence and durability analysis, and overall monitoring in place. Protocols vary depending on project type, making the fungibility of different projects, particularly nature-based versus engineered, complex and ambiguous.

Large-scale CDR will affect atmospheric carbon concentrations in a measurable way, but because of the complexities inherent to the global carbon cycle, 1 gigaton (Gt), or 1,000 million

tonnes, of carbon removal will reduce atmospheric concentrations by less than 1 Gt (Wilcox et al. 2021), and that discrepancy should be accounted for in any carbon-crediting or offsetting paradigm. An airport then would need to rely on a certification process and institution that is credible to certify carbon-removal projects on-airport or, if purchased through a third party, off-airport.

There is an additional need for rigorous carbon accounting software, allowing the CDR project to be frequently analyzed and monitored. As of now, a CDR project and insetting efforts will not be a part of the CCM but are more closely related to the VCM. A third-party verifier will need to come in to review the carbon accounting and reporting, and to ensure that the project is neutralizing the owner’s Scope 3 emissions (CarbonCredits.com 2022). There are many useful resources and verification organizations in the United States.

The primary carbon registries in the VCM include the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS), the Gold Standard, the Climate Action Reserve, the American Carbon Registry, and the Plan Vivo (Merchant et al. 2022). The U.S. Berkeley Carbon Trading project tracks the credits, and, according to their database, VCS has issued more than two-thirds of the credits in the VCM as of April 2022, with the other registries having a much smaller market share (Ivy, Haya, and Elias 2023). Many of the carbon registries use a variety of standards to issue the carbon credits and have their own methodologies for review and registry approval and use third-party verification of offset projects. (Although the project research team worked to differentiate between credits in the CCM and offsets for the VCM, there will be some uses in the document that use credits when talking about the VCM because that is the way it is referenced by the company.) This third-party verification can range widely from desktop reviews to site visits confirming conditions (Merchant et al. 2022). Carbon offsets have been in the news with criticism about the actual benefits tracking the offsets, many times because there is a financial relationship between developers and third-party registries (Merchant et al. 2022).

There are also a few new registries that are focused specifically on CDR projects (Nori and Puro are examples), but for most CDR approaches, few third-party standards or registries exist. With new CDR techniques rapidly evolving, consistent standards around certification are needed.

Land-use techniques provide an additional challenge, and determining how to measure and credit the carbon-removal gains is extremely challenging due to the complexity of the system. There are more than a dozen soil carbon protocols developed, each with different detailed rules for developing an offset to be sold to buyers—the criteria include scientific rigor, additionality, and durability. Review of these protocols by researchers indicated that most protocols did not include adequate soil sampling quality, had little reliance on empirical measurements, and offered low assurance of additionality. Summary of the research indicated “In the vast majority of cases, the standards set by these protocols cannot be used to provide confidence around project quality. Buyers can’t rely on existing protocols to know whether a project was rigorously credited, and sellers can’t invoke or rely on the status quo rules to demonstrate quality. The question of defining a good project must be answered, instead, outside the voluntary market’s formal rules” (Zelikova et al. 2021). These challenges around land-use CDR techniques would make it difficult for airports to adequately track and get certifiable and scientifically supported credits.

1.4.7 Airports and the Carbon Market

There are several voluntary programs that support airports in developing GHG inventories, emission-reduction goals, climate action plans, and net-zero roadmaps. Currently, in the United States there are no regulations requiring accounting, tracking, and reducing CO2 emissions at airports. Airports can be industry leaders by participating in voluntary programs and signing reduction commitments. The Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) is the sole international offsetting scheme for the aviation industry currently and

is focused on airlines (not airports). CORSIA is a global market–based mechanism designed to offset the carbon emissions from international aviation. CORSIA was established by the ICAO, a specialized agency of the United Nations that sets standards and regulations for international civil aviation. CORSIA requires airlines to measure, report, and offset their emissions by purchasing carbon-offset credits. Under CORSIA the offsets are currently voluntary but will become required in 2027 (with some exemptions for operators with a low level of annual emissions, smaller aircraft and humanitarian, medical, or firefighting operations).

Airports currently participate in the VCM primarily through the purchase of offsets. As described previously, the ACA program requires offsets to get to certain levels (Level 3+). This is typically done through a third-party vendor that meets certain standards and is typically implemented by a developer off-airport. ACA has published three offsetting manuals, available on their website. However, to reach the recent (December 2023) Level 5 (net zero), an airport will need to remove their residual emissions through carbon-removal offsets that are approved through the ACA requirements. Outside of the ACA program, airports can also participate in the VCM through the purchase of voluntary offsets, though in these cases, they are not linked to a requirement in an accreditation program.

The potential for airports to participate in the VCM was examined in more detail in ACRP Report 57: The Carbon Market: A Primer for Airports (Ritter, Bertelsen, and Haseman 2011). This report has more information on the relationship between the aviation sector and the VCM, and how airports could potentially use offset projects as a revenue source. The findings in this report indicate that, from a revenue-generation side, developing and selling carbon offsets is limited, due to there not being a federal regulatory system to drive demand, and second, because the types of projects that can be implemented on airports sometimes do not align with the market for selling those offsets (Ritter, Bertelsen, and Haseman 2011). ACRP Report 57 was published in 2011, and while there is still no consistent federal regulatory system for carbon offsets, due to numerous industry net-zero goals, the market for offsets is increasing.

Airport Opportunity

Airports can look to companies such as Microsoft, Amazon, and Google, who are currently driving carbon-removal projects relative to their own net-zero goals.

The market is advancing quickly, and companies like Microsoft are releasing annual updates on CDR challenges and opportunities that could assist airports as technology evolves.

ACRP Project 02-100 builds on some of this discussion and looks at the potential for airports to participate in the carbon market less from the revenue-generation side, and more from the ability of airports to create carbon-removal projects to meet their net-zero goals. There is a need for airports and their operators to be leaders in advancing and implementing CDR, rather than just purchasing carbon-removal offsets in the carbon market.

There are many different CDR strategies and pathways that airports must begin deploying (see the section on insetting). By doing so, airports can remove their own emissions, reach their own and industrywide climate and carbon goals, and help other organizations. At this point, the opportunity to sell additional credits for a profit is likely limited without a federal mandate for carbon limits, but it is something that could provide an additional revenue stream in the future. The challenges around an airport owning a carbon-removal project on-site and other airport-specific constraints are detailed further in Chapter 3.

1.4.8 CDR Ownership Structure

Since airports are not currently regulated to account for carbon, any carbon accounting that an airport does is on a voluntary basis. There are three main ownership structures for CDR at an airport:

- Land lease: An airport leases land to a third-party developer, who then develops the land with the CDR project. The CDR project and offsets are owned by the developer. Offsets are certified to sell to the airport or on the open market.

- Insetting: An airport works to implement a CDR project on airport property that is owned by the airport. The CDR project is an insetting project that an airport implements to contribute to their own CDR goals; the airport likely does not have excess credits to sell on the open market.

- Carbon-removal offset purchase: A third-party developer for a CDR project off-site purchases a carbon-removal offset. This could be done in conjunction with the city or county.

As described in the certification section, under all these scenarios it is expected that a third-party certifier would need to be involved to appropriately ensure the validity of the carbon-removal offsets, either for land-use techniques or for the more technologically based pathways.

There may be additional opportunities for partnerships for airports that are owned by a city, county, or port authority and those that are operated by the state. Many airports are owned and operated by or affiliated with a larger organization, such as a city, county, or port authority. Airports could work with their owners to leverage city, county, or port-authority partnerships to look at land use, siting opportunities, and funding. To collaborate with all potential partners is key to create the most affordable and efficient CDR project.

1.4.9 Lessons Learned from Microsoft

Microsoft is leading the global effort in making CDR mainstream, reducing emissions, and removing all legacy company emissions since establishment. Microsoft has committed to being carbon negative by 2030 and targets removing all its historic emissions by 2050. Since establishing its carbon-negative 2030 goal in 2020, Microsoft has published multiple white papers on CDR focusing on the challenges, successes, and other lessons learned through its portfolio. Microsoft’s work is highly pertinent to airports because it shows how rapidly the field is evolving, and the complexity around the language, consistency, and approach to adequately include carbon removal as part of a net-zero roadmap.

Over the years, Microsoft has found a need for cross-organizational collaboration, developing a common language and criteria, increasing global oversight and leadership, and overall scaling of engineered CDR. Without a robust common language, definitions, standards, and criteria, each organization is required to do its own diligence; this is both inefficient and creates opportunity for human error.

There are also different assumptions made for carbon-project impacts, creating challenges related to comparability. Microsoft states that a key takeaway for them is that “the market lacks clear carbon removal accounting standards, particularly around the criteria of additionality, durability, and leakage” (Microsoft 2021). Additionality refers to the degree to which a CDR project causes a climate benefit above and beyond what would have happened in a no-intervention baseline scenario (Wilcox et al. 2021). Durability (or permanence) refers to the duration for which CO2 can be stored in a stable and safe manner (Wilcox et al. 2021). Leakage refers to initially stored CO2 (or other GHGs) that has left its storage state and returned to the atmosphere. Examples of these additionality, durability, and leakage include combustion of a fuel made from CO2, burning of biomass, and migration of CO2 from underground storage (Wilcox et al. 2021). In the 2023 report, Microsoft expresses concerns regarding the inclusion of equity and environmental justice throughout the planning, design, and development of CDR projects. Collaborating with partners who prioritize equity in their projects has proven to be challenging, as it is difficult to balance CDR and social equity and justice in projects.

Fortunately, many capitally intensive organizations like Amazon, Apple, Climeworks, Google, and others are investing in improving the existing carbon markets. There are also financing

options available, such as multiyear purchase agreements, that are analogous to power purchase agreements for renewable energy. These types of agreements may be pertinent to airports and how they can help drive the carbon-removal market, as similar power purchase agreements drove the implementation of solar at airports starting a decade ago. In its most recent report, Microsoft states that they are seeing many projects that rely on public and private funding to come to fruition (2023). Changes in the available grant funding have assisted (see Chapter 6 for more information). Without using corporate offtake agreements and public subsidies, many of the CDR projects in development would not exist. Although Article 6 of COP 26 does encourage the use of carbon markets between countries, Microsoft claims that this practice falls short. Rather than determining the criteria for and defining high-quality carbon removal, COP 26 passed the task on to future groups (Microsoft 2022).

Microsoft is working on developing and deploying engineered CDR technology, but nature-based solutions remain as most of the portfolio. Microsoft focuses on creating a diverse portfolio by taking an “all of the above” approach (Microsoft 2023). It is important to avoid solely relying on one CDR pathway. Forestry and soil CDR have low durability and are vulnerable to climate and human impacts, but they remain some of the best options. Microsoft has asked the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) for support in creating high-quality standards, clear accounting methods, and scaling opportunities. The 2023 Microsoft report considers enhanced mineralization (e.g., enhanced rock weather) and BiCRS/BECCS as high-durability CDR pathways. Overall, Microsoft encourages corporations and registries to develop more robust science-based benchmarks for leakage, additionality, durability, and baselines.

Many large, global corporate companies and governments have made ambitious carbon-reduction goals that align with science-based targets and the IPCC reports. Microsoft, and other leading corporations, have found a gap in the supply of high-quality and high-durability CDR. In January 2021, Microsoft expressed its concern, “to source the volume that we need by 2025, we will need a portfolio of at least several medium-sized or large CDR projects (more than 100,000 Mt CO2 of removal each)” (Microsoft 2021). As more organizations begin to investigate CDR, and more capital is invested into this sector, there is optimism that the high-durability technology will scale in capacity, access, and affordability. Microsoft discusses the urgency to begin planning, sourcing projects, and signing purchase agreements as soon as possible if an organization has set goals to have CDR projects in its portfolio by 2030 (Microsoft 2023).