Implementation of Federal Highway Administration Proven Safety Countermeasures (2025)

Chapter: 4 Case Examples

CHAPTER 4

Case Examples

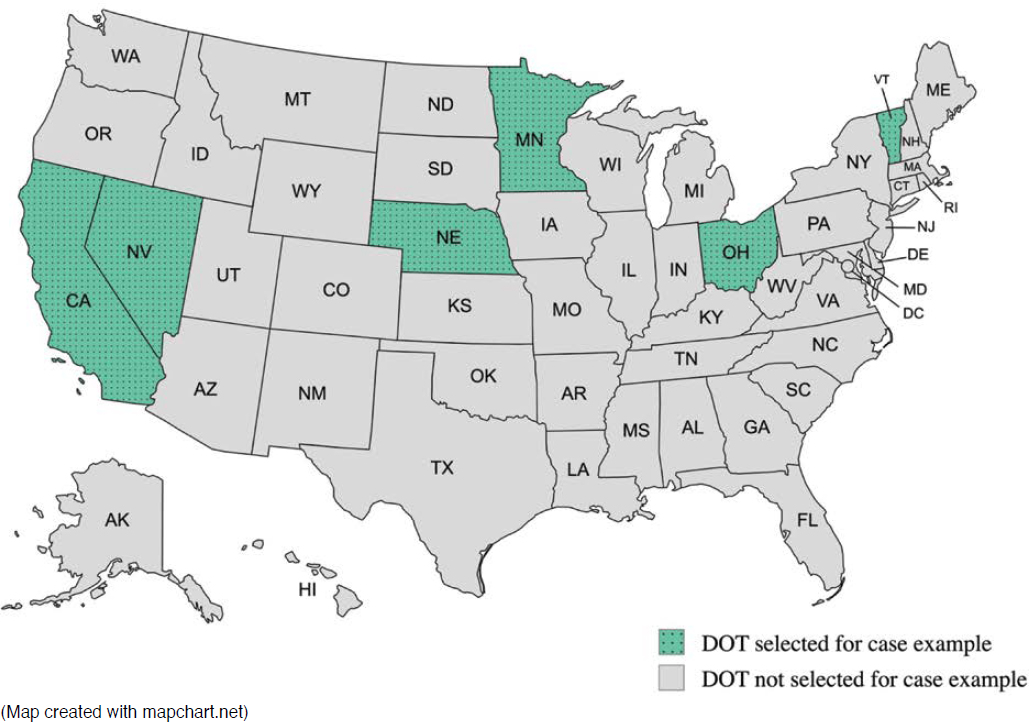

This chapter presents case examples for the use of FHWA PSCs by six DOTs (Figure 64): California, Minnesota, Nebraska, Nevada, Ohio, and Vermont. In consultation with the topic panel, the criteria considered as a basis for choosing the DOTs for the case examples include

- Diversity with respect to geography, level of experience, number and type of FHWA PSCs implemented, stages of implementation, customizations, and implementation challenges;

- Some preference was given for states with topic panel members; and

- Willingness to participate in a case example, as indicated in the survey.

Table 14 lists the DOTs selected for the case examples along with their number of Institutionalized FHWA PSCs and basis for selection as a case example.

The case examples were developed based on phone interviews with personnel from the six DOTs. Typical case example interview questions are provided in Appendix C. Some of the topics for FHWA PSCs during the interviews include

- General approach and experience,

- Implementation processes,

- Challenges and strategies to overcome those challenges,

- Implementation concerns with specific FHWA PSCs,

- Internal assessment of implementation of PSCs,

- Development of resources (e.g., guidelines, templates, and prompt lists) to support FHWA PSCs,

- Partnerships with other agencies, and

- Suggested enhancements to FHWA’s PSC initiative.

The case examples are described in the following sections of this chapter. The definitions used for implementation stages are the same as the definitions in the Survey Results chapter. An Institutionalized PSC may or may not be Standard Practice.

California Department of Transportation

Overview of Caltrans’ Use of FHWA PSCs

The California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) has implemented 26 of the 28 FHWA PSCs to some extent. Caltrans has institutionalized 25 of the FHWA PSCs, and all 25 of these PSCs are standard practice for the agency. In addition, Caltrans has implemented SSCs and VSLs to some extent. Caltrans makes use of various funding sources (e.g., safety maintenance funds or project funds) for its implementation of FHWA PSCs.

Caltrans’ Practices for FHWA PSCs

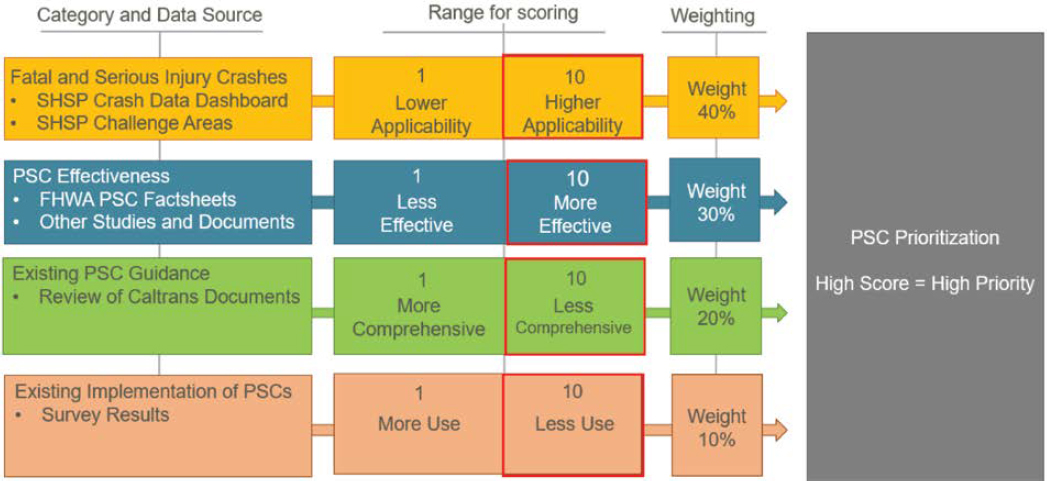

Caltrans often consults FHWA’s PSC resources during the development of safety projects. Caltrans has also developed its own resources for many FHWA PSCs, and the agency has a state MUTCD with information on several PSCs (Caltrans 2024b). In 2024, the agency completed a study to prioritize the PSCs for the development of guidance (Kimley-Horn and Associates 2024a). As shown in Figure 65, criteria used for the PSC prioritization included fatal and serious injury crashes, PSC effectiveness, existing PSC guidance, and existing implementation of PSCs. As part of the study, a practitioner survey was conducted that covered topics such as the familiarity of each PSC, the level of implementation of each PSC, the ease of access to current PSC resources, and PSC recommendations. Survey responses were received from 40 Caltrans practitioners with a role in implementing PSCs. The study identified the following FHWA PSCs as the highest priority for the development of guidance: pavement friction management, RSAs, LRSPs, and SSCs. These PSCs will be in the first group of PSCs for the development of guidance, with the goal of developing guidance for all 28 FHWA PSCs in one document.

The Caltrans Traffic Safety Engineering group oversees and coordinates Caltrans’ efforts regarding the implementation of PSCs. Caltrans has begun to provide outreach training for its district personnel to help increase awareness of FHWA PSCs. Caltrans provides a webpage with links to various resources from FHWA, Caltrans, and other agencies for all 28 PSCs (Caltrans 2024a).

Some of the general implementation challenges Caltrans has experienced in using FHWA PSCs include outreach and education, shifting to a proactive approach to safety, maintenance concerns (e.g., tape can peel off for backplates with retroreflective borders), and regulatory barriers.

Table 14. Overview of case examples.

| DOT | Basis for Selection as Case Example | Number of Institutionalized FHWA PSCs* |

|---|---|---|

| California |

|

25 |

| Minnesota |

|

17 |

| Nebraska |

|

11 |

| Nevada |

|

1 |

| Ohio |

|

26 |

| Vermont |

|

14 |

* As provided in the survey response.

Caltrans includes maintenance personnel as stakeholders for FHWA PSCs and incorporates their feedback into its PSC practices. Caltrans is limited in using SSCs and VSLs by regulatory barriers.

Caltrans partners with local agencies in implementing FHWA PSCs by providing them with resources on FHWA PSCs. In addition, Caltrans included local and regional partners in three stakeholder meetings that were conducted to discuss the PSC guidance implementation plan (Kimley-Horn and Associates 2024b).

Other Caltrans Considerations for FHWA PSCs

Caltrans is working on the development of state-specific CMFs and is beginning a project to develop guidance for all 28 FHWA PSCs in one document. The development of this guidance is divided into four groups of seven PSCs, with a timeframe of 6 months for each group and an overall completion date of June 2026 (Kimley-Horn and Associates 2024a).

Caltrans would like to learn about the experiences of other state DOTs in overcoming challenges to the use of FHWA PSCs such as SSCs. Caltrans finds the FHWA PSC website (FHWA 2024a) to be a valuable tool but has seen some confusion regarding the interpretation of the crash data on the website because of differences in the types of crash severity that are reported for the PSCs. Caltrans sees an opportunity for enhancement of the FHWA PSC website by posting tables or data for all PSCs regarding CMFs and crash severity that are easily distinguishable and comparable for each PSC.

Minnesota Department of Transportation

Overview of Minnesota DOT’s Use of FHWA PSCs

The Minnesota Department of Transportation (Minnesota DOT) has implemented 26 of the 28 FHWA PSCs to some extent. Minnesota DOT has institutionalized 17 of the FHWA PSCs, and three PSCs (longitudinal rumble strips and stripes on two-lane roads, SafetyEdge, and wider edge lines) are standard practice for the agency. Of the 28 FHWA PSCs, Minnesota DOT most frequently considers median barriers, reduced left-turn conflict intersections, roundabouts, and lighting for use on projects. Minnesota DOT uses HSIP as the most direct funding source for FHWA PSCs but also leverages other funding sources and its regular program to implement FHWA PSCs. FHWA PSCs that are standard practice are typically funded through the project.

Minnesota DOT’s Practices for FHWA PSCs

Minnesota DOT utilizes the FHWA PSC list as a primary resource when developing project type recommendations for its safety plans. Minnesota DOT generally implements the FHWA PSCs based on selecting treatment types instead of specific locations or specific projects. Minnesota DOT’s district traffic offices take the lead on the implementation and management of FHWA PSCs, and Minnesota DOT’s Central Traffic Office provides implementation support for the districts and counties by helping to promote the use of FHWA PSCs, assisting with finding funding and prioritizing sites, and providing crash data for analysis. Minnesota DOT

also worked with counties in the development of LRSPs and has developed resources for nine of the PSCs.

Minnesota DOT has performed safety evaluations for several FHWA PSCs and has an ongoing contract in place to assess various traffic safety countermeasures and implementation efforts. For example, an evaluation of backplates with retroreflective borders did not find a statistically significant crash reduction associated with their use (Moreland et al. 2024). However, Minnesota DOT believes this finding may be because of the standardization of signal equipment and features (e.g., 12-inch ball, one signal head per lane) on many of its traffic signals, as many typical safety features used with traffic signals are standard equipment for signals on trunkline highways. Results from a study of roundabouts with high levels of use by pedestrians and bicyclists found that the use of the roundabout led to reductions in pedestrian and bicyclist crashes of 70% (fatal and injury) and 15% (total) (Wagner et al. 2023). Minnesota DOT finds demonstrating past successes for FHWA PSCs to be helpful in convincing local communities, elected officials, and other stakeholders that proposed PSCs will be effective for a given project.

Some of the general implementation challenges Minnesota DOT has faced in the use of FHWA PSCs include maintenance concerns (e.g., pedestrian refuge islands, snow clearing for cable barriers) and public perception. Minnesota DOT consults maintenance personnel for feedback regarding FHWA PSCs. In addition, Minnesota DOT has enhanced its initial public involvement efforts to get more engagement from stakeholders in the decision-making process.

Regarding specific countermeasures, SSCs have not previously been allowed by state law. However, Minnesota recently passed legislation allowing two cities to pilot SSCs and instructing Minnesota DOT to perform SSC pilots in two to four work zones in the upcoming years. Minnesota DOT is implementing backplates with retroreflective borders less often as it is not seeing significant safety benefits associated with their use. Minnesota DOT sees fewer opportunities to implement FHWA PSCs for pedestrians and bicyclists because of the mostly rural nature of the state. In implementing wider edge lines, Minnesota DOT has experienced some paint shortages in the past that led to higher costs. Minnesota DOT prioritized locations for cable median barrier installation and has installed cable median barriers on approximately 900 of its 1500 miles of multi-lane divided highway. Minnesota DOT is installing cable median barriers in areas where the benefit is not as great as past installations and believes that the best opportunities for crash reductions using cable median barriers are nearing completion, especially with rising costs. Minnesota DOT implements corridor access management guidelines on its routes (although typically not through projects directly focused on corridor access management but through other means) but finds corridor access management on local roads to be challenging.

Minnesota DOT has made modifications to some of the FHWA PSCs to facilitate implementation. For example, Minnesota DOT utilizes sinusoidal rumble strips (see Figure 66) to address noise concerns and has found that they provide similar safety performance to rectangular rumble strips (Storm et al. 2023). Minnesota DOT also made some minor changes to the federal standard for SafetyEdge. For new installations of reduced left-turn conflict intersections, Minnesota DOT may no longer provide a median opening and thus may require U-turns for the left-turn movement from the major road. Figure 67 shows an example of a reduced left-turn conflict intersection in Minnesota with mainline left-turn access provided. Minnesota DOT’s VSLs are only advisory because of state law and have been used sparingly.

Other Minnesota DOT Considerations for FHWA PSCs

Minnesota DOT is working toward expanded use of LPIs, development of guidelines for LPIs, updating its guidance for corridor access management to make it more prescriptive, providing local agencies with additional guidance on implementing FHWA PSCs, and incorporating

FHWA PSCs earlier in the project development process. As part of U.S. DOT’s Allies in Action campaign, Minnesota DOT made several commitments related to reduced left-turn conflict intersections (installing at more locations, evaluating a new policy for standardizing the design of left-turn conflict intersections on expressways, and implementing a toolkit to enhance awareness of safety benefits) and SSCs (completing a synthesis to identify challenges faced by other state DOTs and working with stakeholders for exploration of SSCs) (U.S. DOT n.d.). Minnesota DOT is interested in learning more about processes used by other state DOTs to implement PSCs as standard practice.

Minnesota DOT finds the FHWA PSCs to be a valuable resource, as the federal support for their use helps to alleviate stakeholder concerns. Suggested Minnesota DOT enhancements

for FHWA’s PSC initiative include adding information on conditions that may not be suitable for the use of specific PSCs and the development of short informational videos on PSCs.

Nebraska Department of Transportation

Overview of Nebraska DOT’s Use of FHWA PSCs

The Nebraska Department of Transportation (Nebraska DOT) has implemented 25 of the 28 FHWA PSCs to some extent. Nebraska DOT has institutionalized 11 of the FHWA PSCs, and six PSCs (crosswalk visibility enhancements, enhanced delineation for horizontal curves, longitudinal rumble strips and stripes on two-lane roads, SafetyEdge, yellow change intervals, and RSAs) are standard practice for the agency. Nebraska DOT most frequently considers RRFBs, road diets, and roundabouts for use on projects. Nebraska DOT typically funds the implementation of FHWA PSCs using HSIP funds. However, state funds are sometimes used for pilot projects.

Nebraska DOT’s Practices for FHWA PSCs

Nebraska DOT generally bases its approach to the implementation of FHWA PSCs on cost effectiveness and achieving the highest reductions in crash fatalities and serious injuries. Nebraska DOT uses the FHWA PSC list as a starting point to implement new safety countermeasures or to find CMFs for a safety countermeasure. Nebraska DOT periodically reviews safety research to help assess the costs and benefits of FHWA PSCs. When first implementing a FHWA PSC, Nebraska DOT often uses pilot projects to evaluate its effectiveness in Nebraska and to assess state-specific implementation considerations, such as public perception and design criteria. The agency performs before-after studies for all HSIP and pilot projects. As the use of a given FHWA PSC becomes more widespread, Nebraska DOT establishes policies for that PSC. Nebraska DOT has developed resources for almost half of the PSCs.

Some of the general implementation challenges Nebraska DOT has faced include getting buy-in to the safety research, educating the public about FHWA PSCs, and finding pilot projects for FHWA PSCs. Regarding implementation concerns for specific countermeasures, Nebraska DOT does not use the following FHWA PSCs: appropriate speed limits for all road users, SSCs, and backplates with retroreflective borders. Nebraska DOT performed some testing of USLIMITS2 but obtained similar results to its process of using the 85th percentile speed based on the MUTCD (FHWA 2023a). SSCs are not allowed by Nebraska state law. Nebraska DOT perceives a need for additional research regarding safety outcomes for backplates with retroreflective borders. Nebraska DOT also limits its use of pavement friction management because of issues with delamination encountered on previous projects. In addition, Nebraska DOT prioritizes installing single-lane roundabouts because of observed crashes with a prior multi-lane roundabout installation.

Nebraska DOT has made modifications to some of the FHWA PSCs to facilitate implementation. For example, after experiencing issues with materials for rumble strips, Nebraska DOT made some modifications to its standards for rumble strips and now only installs them on new pavement. For centerline rumble strips, Nebraska DOT increased the gap to avoid pavement joints and strengthened the joints. Nebraska DOT has also installed modular roundabouts (see Figure 68 as an example) to improve the cost effectiveness of roundabouts and accelerate construction. Nebraska DOT also lowered the threshold for 2-foot paved shoulders with edge line rumble stripes to 1,000 vpd. Nebraska DOT implements variable advisory speed limits because VSLs are not legally permitted in Nebraska.

Regarding implementation strategies, Nebraska DOT tries to be selective in its use of FHWA PSCs to help ensure success and avoid implementation challenges that could hinder future

efforts to implement that PSC on other projects. For example, new roundabouts are typically considered for installation at locations near existing roundabouts where drivers are more familiar with roundabouts. Nebraska DOT is also very selective in identifying locations for reduced left-turn conflict intersections and considers this PSC for intersections on multi-lane divided highways with a high frequency of severe crashes and no sight distance issues. Nebraska DOT also finds that bundling FHWA PSCs for multiple locations in a project can be effective (e.g., incorporating rural lighting for multiple locations in one project).

Nebraska DOT partners with local agencies in implementing FHWA PSCs. For some systemic projects (e.g., installing new signs at curves or intersections), Nebraska DOT purchases the materials for the safety countermeasures using HSIP funds, and the local agencies install the countermeasures. Nebraska DOT finds many municipalities implementing LPIs. Nebraska DOT has also partnered with several counties on the development of LRSPs.

Other Nebraska DOT Considerations for FHWA PSCs

Nebraska DOT performs periodic evaluations of its safety program and finds that its understanding of FHWA PSCs continues to grow. The agency is working on developing a pedestrian level lighting standard, increasing its use of countermeasures at intersections, and implementing cable median barriers. As part of U.S. DOT’s Allies in Action campaign, Nebraska DOT committed to upgrading signing at over 6,000 stop-controlled county road intersections and updated its rumble strips policy to expand implementation by removing minimum AADT requirements (U.S. DOT n.d.). Nebraska DOT is also working on resolving concerns about construction and maintenance costs of cable median barriers and would like to see additional information on injury level CMFs for installing concrete median barriers compared to cable median barriers or steel w-beam median barriers. Nebraska DOT has constructed one diverging diamond interchange and is working toward expanding its use of diverging diamond interchanges in the future.

Nebraska DOT is interested in learning about the experiences of other state DOTs in using FHWA PSCs, including success, challenges, and strategies used to overcome those challenges. Nebraska DOT would also like to see additional information on CMFs for adding or widening a pavement shoulder for the roadside design improvements at curves PSC and information on average benefit-cost ratios for PSCs.

Nevada Department of Transportation

Overview of Nevada DOT’s Use of FHWA PSCs

The Nevada Department of Transportation (Nevada DOT) has implemented 26 of the 28 FHWA PSCs to some extent. Nevada DOT has institutionalized SafetyEdge and made it a standard practice. Fifteen of the FHWA PSCs are in the Demonstration Stage at Nevada DOT. Nevada DOT typically funds the implementation of FHWA PSCs using HSIP funds with some supplementation from general project funds.

Nevada DOT’s Practices for FHWA PSCs

Nevada DOT utilizes the FHWA PSC list as a first step in developing potential countermeasures for a project. Nevada DOT also consults CMFs and the Highway Safety Manual (AASHTO 2014) when considering which safety countermeasures to implement. Nevada DOT performs before- and-after studies (3 years of before data, 3 years of after data) to assess the performance of FHWA PSCs after implementation. In addition to formal assessments, Nevada DOT also sometimes evaluates FHWA PSCs based on informal observational data. For example, the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe reported reduced speeds after a shared-use pathway (see Figure 69) was installed in their community. The shared-use pathway is located on the east side of SR 447 in Washoe County and provides opportunities for safe crossing for the community to access the elementary school and community center on foot.

Nevada DOT’s Traffic Engineering Division, which includes approximately 10 engineers and seven analysts, oversees the implementation of FHWA PSCs. Nevada DOT has developed resources for three FHWA PSCs (longitudinal rumble strips and stripes on two-lane roads, SafetyEdge, and backplates with retroreflective borders). Other safety countermeasures emphasized by Nevada DOT include recoverable slopes and proper signage.

A primary challenge encountered by Nevada DOT in the implementation of FHWA PSCs is internal and external resistance, especially for FHWA PSCs that incorporate newer concepts

(e.g., reduced left-turn conflict intersections, PHBs). Nevada DOT finds it difficult to implement pilot projects for FHWA PSCs because of stakeholder concerns. For example, a pilot project near Lake Tahoe that included speed management and repurposing of pavement for bicyclists was met with strong public resistance. Nevada DOT is working toward increasing public awareness of FHWA PSCs.

Other challenges faced by Nevada DOT in the implementation of FHWA PSCs include communicating with the public and stakeholders regarding speed management, the need for PSC champions, interactions between FHWA PSCs, and the need for funding and training for the maintenance of PSCs. Nevada DOT finds that conversations with the public and stakeholders regarding speed-related topics can be challenging and speed management sometimes needs to be implemented indirectly. In addition, Nevada DOT sees that some FHWA PSCs need complementary PSCs to improve safety performance. For example, crosswalk visibility enhancements may require large-scale speed management strategies (e.g., road diets) to achieve a safety benefit.

Regarding implementation concerns for specific FHWA PSCs, Nevada DOT does not utilize SSCs because they are prohibited by state statute. Nevada DOT also encounters maintenance challenges with wider edge lines because waterborne paint markings need to be restriped every 6 months because of Nevada’s climate. Nevada DOT also has maintenance concerns with FHWA PSCs that involve electronics. For example, the agency is working with its Operations group to address concerns regarding PHBs (e.g., operation during power outage). In addition, the agency has paused its use of RSAs because of concerns with RSA findings not being implemented on projects.

Nevada DOT partners with local agencies and tribal communities in implementing FHWA PSCs. Nevada DOT encourages involvement from local agencies in the development of its SHSP but finds it challenging to get local communities engaged with LRSPs. The agency has a consultant and funding source for LRSPs and is working with two counties and one city on LRSP development. Nevada DOT has a tribal liaison and partners with tribal communities on safety improvements. In Nevada DOT’s experience, implementing FHWA PSCs for tribal communities can be challenging because of the lack of crash data on tribal lands.

Other Nevada DOT Considerations for FHWA PSCs

Looking to the future, Nevada DOT is working toward implementing risk-based analyses for FHWA PSCs, enhancing methods for regular assessment of PSCs, partnering with local communities, and finding ways to utilize pilot projects for PSCs. Nevada DOT is also seeking to expand the implementation of corridor access management, speed management, pavement friction management, and road diets. Nevada DOT indicated to FHWA that it would specifically champion wider edge lines and LRSPs and is working toward getting more equipment for the placement of wider striping. Nevada DOT has seen success in implementing roundabouts and is looking to use reduced left-turn conflict intersections in the future. Nevada DOT is currently reviewing and optimizing its RSA practices and plans to re-establish its RSA program once the review is complete.

Nevada DOT is interested in learning about the experiences of other state DOTs with the implementation of RSA findings, deployment of reduced left-turn conflict intersections, and road diets and emergency management. Nevada DOT would also like to see the development of enhanced guidance for appropriate speed limits for all users and wider edge lines. In addition, Nevada DOT also believes that the development of additional guidance for the design and implementation of FHWA PSCs, including actionable steps, would be beneficial.

Ohio Department of Transportation

Overview of Ohio DOT’s Use of FHWA PSCs

The Ohio Department of Transportation (Ohio DOT) has institutionalized all but two of the 28 FHWA PSCs. The two not yet institutionalized include appropriate speed limits for all road users and SSCs, although Ohio DOT is working through tools and policies to try to incorporate these items as well. Ohio DOT is committed to institutionalizing appropriate speed limits for all road users, and in the spring of 2024 they launched a $25 million pilot program that provides funding to local governments to redesign urban arterials with features that encourage slower motorist speeds. This was also a commitment Ohio DOT made as part of the U.S. DOT’s Allies in Action Campaign (U.S. DOT n.d.). Ohio DOT states that SSCs are currently not under consideration because of regulatory barriers and implementation concerns.

Nearly half of the PSCs are standard of practice in Ohio, with predefined criteria that must be met. These include

- VSLs,

- Enhanced Delineation for Horizontal Curves,

- Longitudinal Rumble Strips and Stripes on Two-Lane Roads,

- Median Barriers,

- SafetyEdge,

- Wider Edge Lines,

- Backplates with Retroreflective Borders,

- Dedicated Left- and Right-Turn Lanes at Intersections,

- Roundabouts,

- Yellow Change Intervals,

- Lighting,

- LRSPs, and

- Pavement Friction Management.

Although not yet the standard of practice, Ohio DOT routinely uses 13 other FHWA PSCs. Of these, they most frequently consider crosswalk visibility enhancements, walkways, roadside design improvements at curves, and corridor access management.

Ohio DOT has not stopped implementing any of the PSCs and has developed resources or guidelines for nearly all PSCs used in the state. Exceptions include road diets, enhanced delineation for horizontal curves, corridor access management, and systemic application of multiple low-cost countermeasures at stop-controlled intersections.

Ohio DOT typically funds the implementation of PSCs using HSIP funds. Additionally, some countermeasures are incorporated into other projects funded by Ohio DOT because of them being institutionalized/standard of practice.

Ohio DOT’s Practices for FHWA PSCs

Ohio DOT has made a larger push to focus on reducing fatal and serious injury crashes. This has encouraged increased reference to the PSC webpage and associated flyers to justify countermeasures. Additionally, the overall promotion of PSCs has been performed by Ohio DOT’s LTAP and its Safety Countermeasures Community of Practice since 2015.

Ohio DOT does not have an official policy or procedure in place for prioritization of PSCs, but generally prefers those with the largest impact on reducing fatal and serious injury crashes. They note that this is evaluated on a project-by-project specific level through their HSIP application

scoring criteria. To achieve a higher score and have an increased likelihood of receiving funding, projects need to present recommendations with high impact. They also try to approach each project with FHWA’s Safe System Hierarchy (Hopwood et al. 2024). Although consideration of FHWA’s Safe System Hierarchy is not formalized anywhere at this time, it will be integrated into their new SHSP in 2025. In 2022, Ohio DOT introduced its systemic safety application program (see overview in Figure 70) that specifically focuses on proactively preventing injuries related to pedestrian and roadway departure crashes.

The primary implementation challenges experienced by Ohio DOT include political involvement and pushback by internal Ohio DOT staff and locals. They note these challenges when it comes to the newer concepts, specifically citing roundabouts, reduced left-turn conflict intersections (see Figure 71), bike lanes, and road diets. They also commonly deal with maintenance concerns.

When evaluating new PSCs, Ohio DOT routinely starts with pilot projects. If the pilot projects go well, design criteria are then developed to be incorporated into all future projects meeting specific criteria. Ohio DOT recently launched a pilot project for target speeds, which will implement a series of countermeasures on high-risk corridors to create self-enforcing roadways. Countermeasures include horizontal and vertical deflection, lane width reductions, lane repurposing, curb extensions, median refuge islands, and hardened centerlines. The pilot project will become a series of case studies, including documentation of results, and it will be used to promote statewide practice.

Ohio DOT partners with local agencies through their safety application process. Local agencies can submit applications for safety funding consideration. Funding is awarded based on a demonstrated need, long-term crash trends, and equity. Funding is available for all stages of project

development and typically requires a 10% local match although exceptions apply. Ohio DOT also allocates $14 million of its annual budget to the County Engineer’s Association of Ohio to fund safety projects. As part of the HSIP reporting process, Ohio DOT formally evaluates the effectiveness of roundabouts, reduced left-turn conflict intersections, and road diets and at a minimum considers the benefits of every project.

Other Ohio DOT Considerations for FHWA PSCs

Ohio DOT also has an ICE policy that is used to evaluate alternative and reduced conflict intersections. They note that this policy has been used on some safety applications to justify an intersection improvement. The target speed program currently under pilot study will consider items such as vertical deflection, raised crosswalks, speed tables, raised intersections, and hardened centerline. Several of these have been funded as part of other projects through Ohio DOT’s systemic safety program.

Ohio DOT is interested in learning if other state DOTs are using anything beyond the standard 28 PSCs. They are also interested in learning more about other state DOTs’ standards of practice for road diets beyond what FHWA has published. Ohio would also like to see the FHWA PSCs prioritized based on the level of impact or enhanced promotion of the use of FHWA’s Safe System Roadway Design Hierarchy document and methodology (Hopwood et al. 2024).

Vermont Agency of Transportation

Overview of VTrans’ Use of FHWA PSCs

The Vermont Agency of Transportation (VTrans) has institutionalized roughly half of the 28 FHWA PSCs. Of the others not institutionalized, all but one are in the Development, Demonstration, or Assessment Stages. VSLs are not being implemented in Vermont.

Six of the PSCs are standard of practice in Vermont, with predefined criteria that must be met. These include

- LPI,

- Longitudinal rumble strips and stripes on two-lane roads,

- SafetyEdge,

- Backplates with retroreflective borders,

- Dedicated left- and right-turn lanes at intersections, and

- Yellow change intervals.

Although not yet standard of practice, VTrans frequently considers the use of bicycle lanes, crosswalk visibility enhancements, walkways, enhanced delineation for horizontal curves, and roadside design improvements at curves.

VTrans primarily cites implementation concerns and staffing or funding constraints as limiting factors to the general adoption of PSCs. They also note a lack of public acceptance and confusion with PHBs, inventory and tracking issues with wider edge lines, and existing right-of-way constraints for lighting. Existing right-of-way constraints that limit the ability to install adequate lighting are especially prevalent in urban or village settings where the environment is built up with sidewalks, utility poles, and other infrastructure that is costly to relocate. Additionally, they identify a lack of information on safety benefits as barriers to VSLs and pavement friction management.

VTrans has developed resources for bicycle lanes, crosswalk visibility enhancements, SafetyEdge, and yellow change intervals.

The agency typically funds the implementation of PSCs using HSIP funds, but VTrans also incorporates safety countermeasures into their capital and paving programs when it makes sense.

VTrans Practices for FHWA PSCs

VTrans HSIP is undergoing a revamp to include more focus on network screening and prioritizing countermeasures by level of risk. As of 2024, prioritization tends to be site-specific, and cost plays a role. Moving forward, VTrans would like to place more focus on systemic screening.

VTrans specifically noted implementation challenges with centerline rumble strips, roundabouts, SSCs, horizontal curve delineation, signal and solar maintenance, PHBs, wider edge lines, and lighting.

- When centerline rumble strips were first installed, some generated noise complaints and a select number of locations had to be removed. Some other locations were installed in error. The error involved the use of trailer-mounted installation equipment that caused the strips to be installed in a non-linear pattern. VTrans has since developed a policy that includes installation specifications to help address these issues. In 2020, the agency also began using sinusoidal centerline rumble stripes on its rural undivided highways. This was after consulting with other northeast states on effectiveness and performance.

- Roundabouts have generated a lot of concern from locals, but as time progresses, VTrans has seen less of this.

- The state of Vermont recently passed legislation to allow a limited pilot study of SSCs, also referred to as Automated Traffic Law Enforcement.

- Horizontal curve delineation (see Figure 72) is an aesthetic concern in the state of Vermont. Locals feel that excessive signage makes the rural scenery less appealing. Issues with pedestrian-signal-related countermeasures (RRFB and PHB) include staffing and resources as well as device reliability. Vermont is a relatively cloudy state, so solar-powered devices do not always work well. VTrans is working to implement specifications to require larger solar panels and batteries, or hard wire where possible. This comes with increased cost, so they are also making sure cost estimates are accurate.

- Vermont does not have a lot of roadways where PHBs make sense, and, where they have been implemented, there have been issues with a lack of public understanding regarding what each of the signal phases means.

- Wider edge lines are a maintenance issue in Vermont. Because Vermont is a heavy snowplow state, water-borne paint is installed on an annual basis. VTrans does not have good documentation regarding what type of pavement marking is installed where, and they have not figured out how to simplify and disseminate information to the contractors regarding where wider edge lines should be painted during the annual routine maintenance.

- VTrans notes that good lighting is costly to install and maintain. While VTrans installs lighting, the agency must be mindful of the cost.

Because of their small size and limited technical expertise, local agencies tend to rely heavily on both regional planning commissions and VTrans for support. The state generally offers support by giving advice or recommendations to local agencies, but it is a local responsibility to act on the advice given. HSIP projects are largely driven at the state level with little local input.

Other VTrans Considerations for FHWA PSCs

VTrans relies on before-and-after studies to assess safety performance. This involves looking at 3 years’ worth of before-and-after data on HSIP-funded safety projects, and considering both whether the countermeasure was effective and whether the project cost estimates were accurate.

Besides the 28 FHWA PSCs, VTrans has also used intersection conflict warning systems, dilemma zone detection with Automated Traffic Signal Performance Measures, and shoulder widening. The primary purpose of shoulder widening is to allow space for bicycle use.

VTrans is interested in learning more about accurately assessing life cycle costs for benefit/cost analysis. They would also like to hear other states’ experiences working through the legislation process to allow SSCs. Implementation on local roads is a constantly evolving process in the state of Vermont. Historically, VTrans has worked with towns and regional planning commissions to help identify locations and projects and lumped projects together where they make sense.

Recently, they have tried moving toward a local or township grant program but have seen issues with navigating the federal funding process. They would like to hear more about how other state DOTs are supporting their locals to incorporate safety countermeasures. VTrans would also find increased guidance on when it may make sense to implement the various PSCs to be beneficial. This could be especially helpful for less technical staff that may be considering the PSCs, such as small municipalities with limited resources.

Vermont also notes that given their size they tend to have much lower traffic volumes and crash frequency than other states. This creates a unique challenge, where smaller “low priority” issues in another larger state become “high priority” in the state of Vermont.

Summary of Case Examples by Topic

The six DOTs described in this chapter have diverse experiences regarding FHWA PSCs. Some of the key findings from the DOT interviews can be summarized as follows.

Key Case Example Findings for Extent of Use of FHWA PSCs

- These DOTs have diverse experiences regarding levels of implementation for FHWA PSCs but have implemented most of the 28 FHWA PSCs to some extent. Among these six DOTs, the number of Institutionalized FHWA PSCs per DOT varies from one to 26.

- The FHWA PSCs most frequently considered for use on projects by these DOTs include RRFBs, road diets, roundabouts, median barriers, reduced left-turn conflict intersections, lighting, bicycle lanes, crosswalk visibility enhancements, walkways, enhanced delineation for horizontal curves, roadside design improvements at curves, and corridor access management.

Key Case Example Findings for Implementation Practices for FHWA PSCs

- Approaches used for implementation of FHWA PSCs include assessing cost effectiveness and achieving the highest reductions in crash fatalities and serious injuries, selecting treatment types instead of specific locations or specific projects, and analyses performed at a project-by-project specific level using HSIP application scoring criteria.

- Various funding mechanisms for FHWA PSCs are used, and the funding source sometimes varies based on the implementation stage of the PSC. Funding sources include HSIP funds, state funds (pilot projects), maintenance funds, and project funds (FHWA PSCs that are standard practice).

- FHWA’s PSC resources are often consulted during the development of safety projects.

- Pilot projects are sometimes used when first implementing an FHWA PSC to evaluate its effectiveness and to assess state-specific implementation considerations, such as public perception and design criteria.

- Example practices used to assess safety performance of FHWA PSCs include before-and-after studies, an ongoing contract in place to assess various traffic safety countermeasures, and informal observational data.

- Some of the general challenges faced by these DOTs in the implementation of FHWA PSCs include staffing or funding constraints, getting buy-in to the safety research, pushback from internal staff and local agencies, outreach and education, public perception (especially for newer concepts such as reduced left-turn conflict intersections, bike lanes, and road diets), finding pilot projects, shifting to a proactive approach to safety, maintenance concerns, regulatory barriers, funding needs, the need for complementary PSCs to improve safety performance, and the lack of crash data on tribal lands.

- Various strategies are used to overcome these implementation challenges for FHWA PSCs, such as including maintenance personnel as stakeholders, enhancing public involvement efforts to get more engagement from stakeholders in the decision-making process, providing outreach and training, and being selective in the use of FHWA PSCs to help ensure success and avoid implementation challenges that could hinder future efforts.

- Examples of challenges to the use of specific FHWA PSCs include

- Implementation concerns and regulatory barriers to SSCs and VSLs (e.g., speed limits for VSLs being only advisory);

- Lack of public acceptance and understanding of PHBs;

- Experience with delamination and need for additional information on safety benefits for HFST;

- Inventory and tracking issues for wider edge lines;

- Paint shortages that led to higher costs for wider edge lines;

- Installation issues (need for proper equipment) for centerline rumble strips;

- Not realizing safety benefits for backplates with retroreflective borders (possibly because of standardization of signal equipment and features);

- Performance of solar-powered traffic control devices in cloudy weather for RRFBs, enhanced delineation for horizontal curves, systemic application of multiple low-cost countermeasures at stop-controlled intersections, and SSCs;

- Existing infrastructure constraints for lighting; and

- Implementing findings for RSAs.

- Example modifications to FHWA PSCs include revising standards for rumble strips and SafetyEdge, limiting the installation of rumble strips to new pavement, developing installation specifications for rumble strips, increasing the gap for centerline rumble strips to avoid pavement joints, modular roundabouts, and sinusoidal rumble strips to address noise concerns.

- DOT partnerships with local agencies in implementing FHWA PSCs are pursued in various ways, such as providing them with resources, including them as stakeholders, assisting with LRSP development, promoting them through LTAP, and providing funding for local safety projects.

Key Case Example Findings for Other Considerations for FHWA PSCs

- Examples of ways these DOTs are working toward enhancing their use of FHWA PSCs in the future include developing state-specific CMFs, creating guidance for all 28 FHWA PSCs in one document, updating guidance for corridor access management to make it more prescriptive, providing local agencies with additional guidance on implementation, incorporating FHWA PSCs earlier in the project development process, implementing risk-based analyses, augmenting methods for regular assessment, finding ways to utilize pilot projects, increasing the use of PSCs at intersections, developing a pedestrian level lighting standard, expanding use of LPIs and developing guidelines for their use, implementing cable median barriers, and conducting a pilot study for a target speed program.

- Opportunities suggested by these DOTs to enhance FHWA’s PSC initiative include providing additional information on average benefit-cost ratios for PSCs to help DOTs prioritize them based on level of impact, posting tables or data for all PSCs regarding CMFs and crash severity that are easily distinguishable and comparable for each PSC, adding information on conditions that may not be suitable for the use of specific PSCs, creating short informational videos on PSCs, and developing additional guidance for the design and implementation of FHWA PSCs (including actionable steps).

- State DOTs are interested in learning about various aspects of other state DOTs’ experiences with FHWA PSCs, such as successes, challenges, strategies used to overcome those challenges, processes used to implement PSCs as standard practice, maintenance practices, use of other PSCs beyond the standard 28 PSCs, supporting local agencies, implementation of RSA findings, deployment of reduced left-turn conflict intersections, and practices for road diets.

Summary of Case Examples by State DOT

A summary of case example findings by state DOT is shown in Table 15.

Table 15. Summary of case example findings by DOT.

| DOT | Number of Inst. FHWA PSCs* | FHWA PSCs of High Focus | Practices for FHWA PSCs | Future Plans or Opportunities for FHWA PSCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| California | 25 (all standard practice) |

|

|

|

| Minnesota | 17 (includes 3 standard practice) |

|

|

|

| Nebraska | 11 (includes 6 standard practice) |

|

|

|

| DOT | Number of Inst. FHWA PSCs* | FHWA PSCs of High Focus | Practices for FHWA PSCs | Future Plans or Opportunities for FHWA PSCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nevada | 1 (also standard practice) |

|

|

|

| Ohio | 26 (includes 13 standard practice) |

|

|

|

| Vermont | 14 (includes 6 standard practice) |

|

|

|

* As provided in the survey response.

NOTE: Inst. = Institutionalized.