Gaps and Emerging Technologies in the Application of Solid-State Roadway Lighting (2024)

Chapter: Appendix C: Characterization of the Effects of Roadway Lighting on Fauna and Flora

CHAPTER 1

Characterization of the Effects of Roadway Lighting on Fauna and Flora

Introduction

Roadway engineers have focused significant attention on the effects of roadway lighting and vehicle headlamps on accident occurrence and outcomes. As discussed through the consideration of the CMF, it is unsurprising that roadway lighting is usually perceived by transportation engineers as an uncontroversial and unproblematic benefit to roadway design. Consequently, roadways are cumulatively the most the most visible feature of cities from space at night (Kinzey et al., 2017; Kuechly et al., 2012; Luginbuhl et al., 2009).

Construction and upgrades to transportation infrastructure such as lighting are, however, subject to environmental review, such as under the federal law (National Environmental Policy Act) and similar state-level laws, which require identification, disclosure, and mitigation of significant adverse impacts on the environment. In this regard, light at night associated with roadways may be seen as a pollutant, adversely impacting flora (e.g., Palmer et al., 2017) and fauna (Bertolotti and Salmon, 2005; Blackwell et al., 2015; Gaston and Holt, 2018). Transportation planners and engineers are faced with the challenge of reconciling the benefits of roadway lighting with the rapidly growing literature on the effects of artificial light at night on species and ecosystems (Gaston et al., 2013; Gaston et al., 2012; Gaston et al., 2014; Hölker et al., 2010; Longcore and Rich, 2004; Rich and Longcore, 2006; Schmiedel, 2001; Verheijen, 1958), when that literature is not organized specifically around roadway or vehicle lighting (but see Bertolotti and Salmon, 2005; Blackwell et al., 2015; Gaston and Holt, 2018). Sometimes studies are explicitly aimed at and about roadways (De Molenaar et al., 2006). Other times roadway lamps are used to create light conditions for studies (Knop et al., 2017).

To address this growing awareness of the ecological impacts of roadway lighting and the need for guidelines for transportation engineers, we have undertaken a review of the literature on artificial light at nighttime and on ecosystems. We have focused on roadway lighting, which is within the purview of transportation agencies, and do not consider lighting from vehicles, which is reviewed by Gaston and Holt (2018). Our goal is to outline the processes by which roadway lighting may affect wildlife species and habitats and identify those mitigating approaches that have been developed with the goal of minimizing such impacts. We then review lighting regulations that have been implemented specifically to protect wildlife and report on a series of case studies of examples of lighting systems designed to minimize the impact of artificial light at night on wildlife.

Roadway Lighting and Species Responses

Roadway lighting is installed in fixed locations and, historically, would run from dusk to dawn. Typically, all lighting of an installation would have similar spectral characteristics that were determined by the lamp type (e.g., mercury vapor, low pressure sodium, high-pressure sodium [HPS], metal halide). As LEDs have become the dominant lamp type in the market, a much wider range of spectral outputs are now available. The effects of light from roadway systems can be categorized by the way light is perceived by

the organism affected. These include changes in radiance and irradiance that are then detected by the sensory or visual system of the organism and result in changes in behavior or physiology. Responses are a dependent on the spatial distribution of light relative to the organism, especially for orientation and movement.

Spectrum, Flicker, and Polarization

Before discussing how light affects organismal responses in different ways, the role of spectrum, flicker, and polarization must be acknowledged.

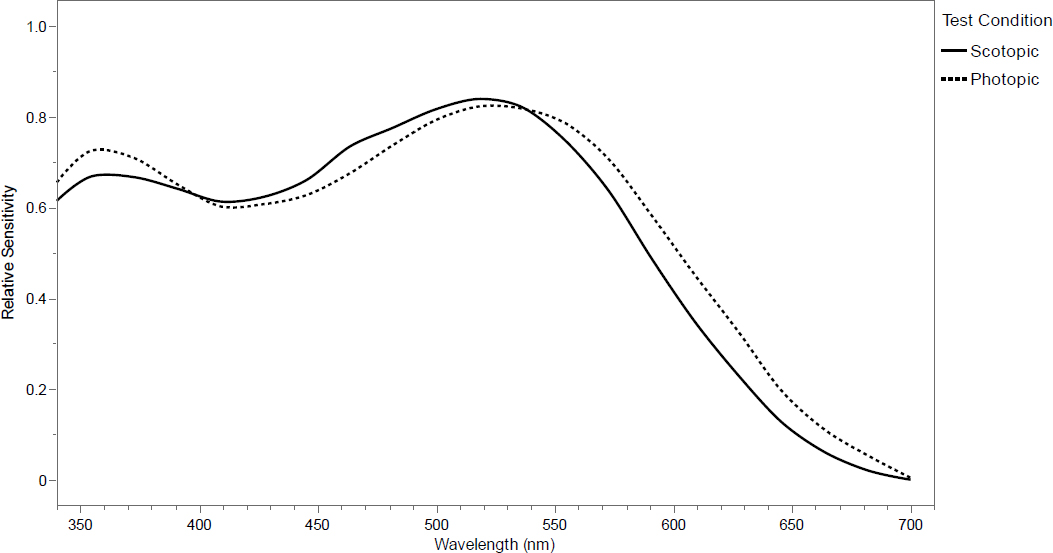

First, the physiological processes by which organisms detect and interpret light vary widely, and although there are similarities among groups of organisms, the sensitivity of these light processing systems varies considerably with light of different wavelengths (Davies et al., 2013; Longcore et al., 2018a) (Figure 1). So, while lighting engineers work almost exclusively measuring light in lux and foot-candles, these measurements reflect the amount of light perceived by the human eye, which may or may not correlate with the perception of other organisms (Longcore and Rich, 2004). When discussing the “brightness” of a light, that perception depends on the organism, and the same number of photons may appear brighter to one species than to another. Changing the spectrum of light may thereby drastically change impacts in different ways for different species (Davies et al., 2013). Discussion of roadway lighting must always recognize that spectral output is inextricably linked to the perception of brightness and that even lights with the same perceived brightness for humans may be different for other species.

Second, some lamps produce light that is not constant and flickers at a constant rate. Humans vary in their ability to perceive flicker and other species vary across a much wider range. The “flicker fusion” rate is the slowest flicker that an individual or organism still perceives as constant light (Simonson and Brozek, 1952). Some whole groups of organisms have much higher flicker fusion rates than humans and therefore perceive some lighting types, such as LEDs, as flashing lights as opposed to constant lighting (Inger et al.,

2014). Research in this area is not well-developed, although it may have significant effects on animal behavior (Inger et al., 2014).

Third, light can be polarized, which means that the photons are all vibrating in a single plane. Although humans cannot perceive light polarization, other species do, and it affects orientation and behavior. Behaviors affected by polarization are common in aquatic insects, especially because light reflected off water is polarized and in the absence of human-made materials is a reliable indicator of water presence (Kriska et al., 1998). Polarization also plays a role in orientation in insects (Dacke et al., 2003; Reid et al., 2011) and fish (Hawryshyn et al., 2010). Because asphalt roadways reflect polarized light, roadway and parking lot lighting is often the cause of “polarized light pollution” (Horváth et al., 2009) as this is the confluence of night lighting, proximity to sensitive species (bridges and roads near water bodies), and a cause of polarization (Egri et al., 2017; Szaz et al., 2015). Because of this convergence of effects, a lighted bridge over a stream or river can act as a complete barrier to dispersal of sensitive species (Szaz et al., 2015).

Of these three lighting attributes—spectrum, flicker, and polarization—the one that will influence lighting impacts on, and mitigation strategies in, nearly all situations is spectrum, although in specific instances other attributes may be more important or have synergistic effects.

Radiance-linked Responses

The intensity of light can be measured as either radiance or irradiance. Radiance is the amount of light being emitted from a source, measured in Watts per steradian per square meter for total radiance, while spectral radiance is the amount of energy measured by the wavelength of light. In layman’s terms, radiance can be thought of as the brightness of a light source. Irradiance, however, is the amount of light that is incident on a surface, measured in Watts per square meter. Correspondingly, spectral irradiance measures the energy incident on the surface by wavelength. Irradiance can be thought of as the degree to which a scene is illuminated. Radiance and irradiance are often measured in units that give luminance (lumens) and illuminance (lux or foot-candles). These units are, however, measurements based on human visual sensitivity and adjustments need to be made when measuring for other species.

The distinction between radiance and irradiance is important because biological processes may be more influenced by one or the other, and they are not always correlated. For example, a streetlight at a distance may appear as a bright point source and have a high radiance, while that same lamp may not result in much increase in irradiance at the same distance. In this instance, the radiance may matter for a species navigating the environment, while the resulting irradiance may be irrelevant.

Roadway lighting results in increased radiance in several ways. First, the lamp itself, if visible, is a source of radiance at high contrast with surroundings during the nighttime (contrast is important for the perception of brightness and associated behavioral responses). This is typically thought of as “glare” and mitigated through shielding. Second, light reflected off surfaces is a source of increased and highly contrasting radiance within a scene. Third, light that is both reflected and scattered in the atmosphere increases sky brightness (referred to as “sky glow”). All of these radiance sources may also increase irradiance at any given receptor’s location, but the radiance and irradiance are likely to influence different biological phenomena. In particular, radiance (as mediated through its spectral composition) influences the orientation of organisms, decisions about nocturnal movement, and consequently the distribution of individuals, with a resulting influence on species.

Orientation and Movement

Attraction, repulsion, and disorientation are possible outcomes of organisms encountering highly contrasting radiant sources, either in response to individual lamps, an array of lamps, or a bright horizon from scattered light. Birds, insects, and turtles provide well-studied examples.

Insects are highly speciose and nearly half of all insect species are nocturnal (Hölker et al., 2010). Many insect species are attracted to light, and this influence may extend a significant distance from light sources (Eisenbeis, 2006; Frank, 2006). Radiance, and in particular a high contrast in radiance, results in greater attractiveness of lamps (Frank, 2006). Spectrum of lamps is quite important, and many studies document the general trend of greater sensitivity to shorter wavelengths (into the ultraviolet) and the resulting influence on attraction (Cleve, 1964; Donners et al., 2018; van Grunsven et al., 2014; van Langevelde et al., 2011b).

For example, in a study on the Indian meal moth, blue light (400–475 nm) was more effective in attracting male and female moths compared to other light colors. The results were the same when researchers used an LED light source with a peak wavelength in the blue-violet range of the spectrum. Increasing the light intensity also increased the attractiveness of the light source to the moths (Cowan and Gries, 2009). In a recent study (Wakefield et al., 2016), attractiveness of four different light sources—tungsten filament, compact fluorescent, cool‐white LED and warm‐white LED—to aerial insects were studied. The results showed that, in general, fewer insects were attracted to the LED light sources. In a similar study, the attraction of moths toward LED, incandescent, CFL, and halogen lamps was examined. The results were similar to the previous study and showed that fewer insects were attracted to the LED source. As a result, it is suggested to use LED sources to reduce the attraction and mortality rate of insects in suburban and urban areas (Justice and Justice, 2016), although because of the wide variability in spectral output of LEDs, this does not hold true for higher correlated color temperature (CCT) LEDs (Longcore et al., 2015; Longcore et al., 2018a).

Different insect species’ attraction to light is determined by their light sensitivity and their body and eye size. For example, larger moth species with larger eyes may be more attracted to light than smaller ones (Yack et al., 2007). Although lighting can be a reason for moth (and insect) population declines (Owens et al., 2020), there are many other contributing reasons as well, such as urbanization, habitat loss (Coulthard et al., 2019), habitat degradation, and climate change (Fox et al., 2014).

Distance between moth habitat and the roadway lighting location can affect attraction toward the light source as well. Degen et al. (2016) estimated that moths will be attracted to high-pressure sodium (HPS) street lighting within a radius of 25 m. Previous research has documented flight-to-light behavior at distances from 3 to 130 m, depending on species and method of measurement (Frank, 2006).

In a study on the effects of traffic-regulated lighting on insect and bat activity at night (Bolliger et al., 2020), researchers added insect traps and bat detectors to streetlights. They dimmed the streetlight levels by 35%. The results showed that insect attraction toward light was highly dependent on weather and site conditions as well as lighting patterns. Increasing the light intensity by 41% on warm and dry nights resulted in a higher number of trapped insects and bat activity, and at the lower light condition fewer insects were trapped.

In a study on the attraction of migrating birds to offshore lights, results showed that birds were more attracted to white, blue, and green continuous light than to red when the sky was not clear. Blinking light also attracted fewer birds (when using red light, the results were the same as the continuous light). Changes in the light intensity did not make any significant change to the results (Rebke et al., 2019).

In another study on birds’ choice behavior of different LED light colors, researchers used blue, green, red, and white LEDs in daylight. Birds tended to avoid blue and red lights and did not have any preference for green or white LEDs (Goller et al., 2018). On the contrary, Poot et al. (2008), in a study on the effect of light color and its wavelength on migratory birds’ wayfinding at night, found that blue and green were less effective in disorienting birds compared to red and white. The results did not change even when the source intensity was changed. Birds have an endogenous magnetic compass that is affected by different wavelengths. Different light sources with different wavelengths can negatively affect their wayfinding. In a response to Poot’s paper, Evans (2010) found some parts of the experiment contradictory and stated that green and blue light should attract more migratory birds compared to red. A study by Gehring et al. (2009)

on birds’ attraction toward towers at night and their fatality rate due to collision results showed that flashing lights attracted fewer birds compared to steady light, with a 50–71% lower fatality rate.

In a study on migratory birds’ stopover density, researchers used weather surveillance radar to assess their population. The results showed that birds’ density was greater near the bright light sources during their migration (McLaren et al., 2018). Additionally, uplights with a high intensity such as New York City’s Tribute in Lights can attract birds and cause a collision with bright structures (Van Doren et al., 2017). As a result, it is important to adopt strategies to reduce light pollution in developed areas.

Street lighting at night affects sea turtle’s nocturnal hatchling orientation. In a study (Bertolotti and Salmon, 2005) on Florida beaches, researchers replaced pole installed lighting (Figure 2) with low-height LED pavement lighting to see if it would keep the beach dark enough for the turtles. The results showed that in clear sky conditions, embedded lighting did not affect turtles’ hatchling orientation. The pole light, a HPS light, had short wavelengths that attracted turtles and were also visible from the shore.

Each of these examples involves attraction, repulsion, or disorientation that is presumably related to the brightness of the light source or an area of the horizon that is brighter. Insects are attracted to light fixtures, birds are attracted to cities and lighted towers during migration, and sea turtles are responding to the direction of the darkest horizon in contrast with either direct or diffuse light sources in another direction.

Fragmentation

The presence of light at night in an organism’s environment can also affect movement over space. The view of bright spots or areas in the nighttime environment may lead to avoidance of certain areas that may be necessary for movement from one suitable habitat to another, thereby fragmenting a species’ range. Studies show that many animals avoid lighted areas at night and their movement in those areas is reduced (Stone et al., 2009). For bats that are sensitive to light, roadways with continuous lighting systems fragment habitats (Hale et al., 2015; Mathews et al., 2015; Rowse et al., 2016). This form of fragmentation has been suggested to affect animals perceiving lights from a distance, such as mountain lions avoiding areas with lights, even when doing so cuts off access to suitable habitat (Beier, 1995). High light (and noise) levels associated with roadways have been associated with reduced use of wildlife crossing structures (e.g., underpasses, culverts) by terrestrial mammals in California (Shilling et al., 2020). These results are consistent with experimental approaches measuring use by mule deer and other smaller mammals of different sections of an underpasses in an experiment with lighting treatments (Bliss-Ketchum et al., 2016), and for bats and artificially illuminated underpasses (Bhardwaj et al., 2020). Connectivity across fragmented landscapes may therefore follow what Pack et al. (2017) call the “darkest path” corridor.

Irradiance-linked Responses

Irradiance is the amount of light incident at a location and can be thought of as the amount of light illuminating a scene. It is often measured as the light coming in from one direction (e.g., horizontal or vertical irradiance), but the more important measure biologically would be light from all directions (scalar irradiance). Roadway lighting alters natural nighttime irradiance through direct illumination, locally reflected and scattered light, and distance scattered light (sky glow). Increased irradiance at any given point is related to radiance elsewhere. Whereas orientation, wayfinding, and movement in motile species is likely most associated with perception of radiance, other responses, including physiological changes, are more closely associated with irradiance at the organism’s location.

Physiological Responses

Physiological responses that alter behaviors or circadian rhythms are associated with sufficient input to photosensory structures within organisms to elicit responses. Such sensory structures include both visual and nonvisual systems. In this section, some of the effects of artificial light at night on melatonin secretion, stress hormone production, reproductive timing, and growth on organisms are presented.

Melatonin

Nearly all organisms have an endogenous clock that has evolved around predictable patterns of light and dark. A substantial body of research shows that artificial light at night would affect these patterns (Cho et al., 2015; Desouhant et al., 2019). Such influences extend to major wildlife groups. Studies on anurans’ (an order of amphibians) development show that they are most sensitive to low wavelengths of light (blue and green) and less sensitive to red. Reptiles, however, seem to have a constant melatonin level that does not relate to their circadian rhythm (Grubisic et al., 2019). In some species, melatonin is regulated by both light and ambient temperature. In a study on reptiles, circadian rhythm results showed that exposure to 300 lux of light for 1 hour at night shifted the melanopic peak earlier (Underwood and Calaban, 1987). However, temperature remains the dominant factor there (Grubisic et al., 2019). Artificial light at night can cause melatonin suppression in birds, but the amount of change and light intensity that will cause suppression is different among different species. In Eurasian blackbirds, light as low as 0.3 lux can cause suppression but only above 1 lux does it have the same effect on Indian weaver birds (Dominoni et al., 2013; Kumar et al., 2018). Additionally, lights with a high amount of blue are more suppressive than warm white sources. There is also a research gap for wavelength-dependent effects of light at night on birds (Grubisic et al., 2019). Studies on non-human mammals show that melatonin levels at night are highly dependent on the light source intensity and emitted wavelengths. Avoiding the use of lights with shorter wavelengths near animal habitats can be a promising strategy to mitigate artificial light at night’s negative impacts on melatonin levels (Dimovski and Robert, 2018; Grubisic et al., 2019).

Stress Hormones.

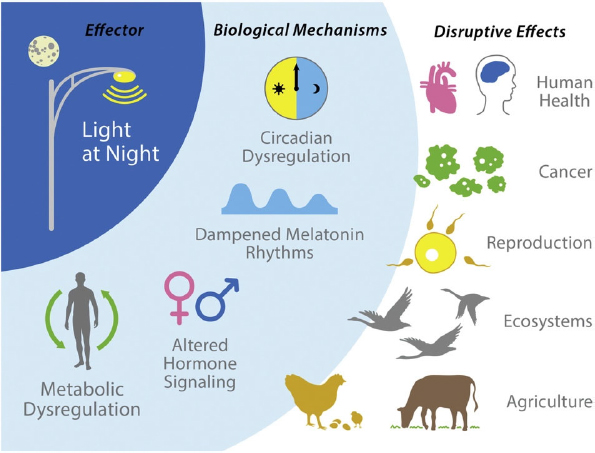

Some studies on captive animals’ stress levels suggest that artificial light in the cage is a source of stress (Morgan and Tromborg, 2007; Varma et al., 2008). Studies suggest that exposure to artificial light at night can cause endocrine disruption in human, plants, and wildlife, which can negatively affect their health and reproduction, as shown in Figure 3 (Russart and Nelson, 2018). In a study on effect of artificial light at night on cortisol in female Siberian hamsters, the results showed that chronic exposure to dim light at night can affect their cortisol levels and circadian rhythm (Bedrosian et al., 2013).

Reproductive Timing and Other Phenological Patterns.

Artificial light at night can also alter reproductive behaviors. Such influences may be physiological, in which lighting suppresses or stimulates hormonal changes (Robert et al., 2015), or behavioral, in which risk of predation influences timing of reproductive activities. As a result, the phenology of organisms is altered, ranging from time of budburst or seed (Bennie et al., 2016; ffrench-Constant et al., 2016; Palmer et al., 2017) to timing of migration (Smith et al., 2020) and clutch date (Havlin, 1964; Lack, 1965; Senzaki et al., 2020) in birds.

Growth Rates

Exposure to unnatural patterns of light at night can affect growth rates of organisms. For example, artificial light at night can adversely affect amphibians’ growth rate in addition to their hormone production and metabolism (Wise, 2007). Such research has used lighting levels that equal those to which amphibians are exposed in wetlands next to roadway lighting. Considerable research has been done on the influence of light at night exposure on developmental rates of chickens. For example, the weight and growth of broiler chickens under 5000 K LEDs was higher than 2700 K LED and 2010 K incandescent sources (Olanrewaju et al., 2015). Another study on effect of monochrome LED light source on male broilers’ body weight and breast muscle weight showed that green light can significantly increase the body weight and breast muscle weight compared to blue light and dark conditions (Zhang et al., 2012).

Foraging and Habitat Use

Irradiance on surfaces within a scene influences perception of that scene by organisms, and thereby informs foraging, hunting, and other aspects of habitat use.

Most bat species refuse to fly and forage in illuminated areas and prefer darker areas at night (Furlonger et al., 1987). For example, the preferred lighting level for Rhinolophus hipposideros bats that would not affect their activity is below 0.04 lux (Stone, 2011). This effect varies by the ecology of individual species, however. In a study on the effects of LEDs, the results showed that lighting levels of 3.6 lux reduced activity of slow-flying bats but had no effect on fast-flying species (Stone et al., 2012).

Habitat use by nocturnal insects is similarly affected by illumination of the environment. In addition to attracting moths, artificial light can influence their feeding patterns. In the field, green light reduced feeding activity by 82%, white light by 72%, and red light by 63% compared to no light controls (van Langevelde et al., 2017).

Alteration in nocturnal foraging behavior in response to scene illumination is also documented in birds, mammals, and other species, consistent with risk mitigation and foraging success associated with different illumination levels.

Communication

Studies show that artificial light can interfere with visual communication and associated reproductive behaviors in bioluminescent organisms (Owens et al., 2020; Owens and Lewis, 2018). Fireflies use low-light situations to start their courtship activities. Fireflies prefer to be active in environments with a light intensity of 0.2 lux or less (equal to light intensity during the full moon). Some of their species are also more tolerant and can be found at sites with light levels between 0.85 lux to 4.5 lux under sodium vapor source (Hagen and Viviani, 2009).

Roadway Mortality

It is possible that through many processes encompassing both attraction (driven by radiance) and habitat use (driven by irradiance), roadway lighting influences mortality of animals in collisions. For transportation engineers, this is usually thought of in terms of animals that are large enough to cause damage in collisions. Larger animals, therefore, have attracted the most attention and research (Mastro et al., 2008; Wilkins et al., 2019).

For ungulates, experimentally installed lighting did not reduce number of accidents per crossing event at a highway in Colorado. In fact, the number of successful crossings by mule deer with lighting was greater than without (Reed and Woodard, 1981). Mule deer did not change crossing locations based on installation of lighting for the experiment (Reed and Woodard, 1981). This is consistent with recent research showing mule deer living at the urban-wildland interface use areas with elevated light levels more than other locations (Ditmer et al., 2020). Other recent research showed a high association between location of mule deer mortality on a freeway and presence of lighting in coastal California (Kreling et al., 2019). In a study in Glenn Highways in Alaska, installation of roadway lighting reduced moose-vehicle collision by 65%, but it is unknown if this reduction was a result of drivers seeing moose and avoiding collisions or if fewer moose entered the lighted area (McDonald, 1991). Research on roadway lighting and large mammal (mostly deer) collisions therefore does not support use of roadway lighting to reduce animal-vehicle collisions.

Many of the other species that are attracted to resources around lights at roadways or to the lights themselves are at risk of additional mortality through collisions that are much less frequently reported. These include impacts on bats (Bhardwaj et al., 2020), raccoons (Kreling et al., 2019), insects, amphibians, reptiles, and birds, either through direct attraction or attraction to other species attracted to lights.

Roadway Lighting Impact on Flora

The impact of roadway lighting on plants is an intersecting consideration. Unlike animals, where the eyes and the photoreceptors determine the response of the species to light, plants absorb light through their leaves and stems to convert water and carbon dioxide to carbohydrates for energy and emit oxygen.

Photosynthesis

This process is known as photosynthesis and relies on the presence of chlorophyll. In the light-dependent reactions, a molecule of the pigment absorbs a photon and loses an electron to trigger the photosynthesis reaction.

Typically, light from a source is measured in lumens. However, as previously mentioned, the definition of the lumen is based on human visual response and cannot be used to measure the quality of light for plants. Light energy incident on the plant is measured as photosynthetically active radiation (PAR). PAR is the amount of light available for photosynthesis in the 400 to 700 nm wavelength range.

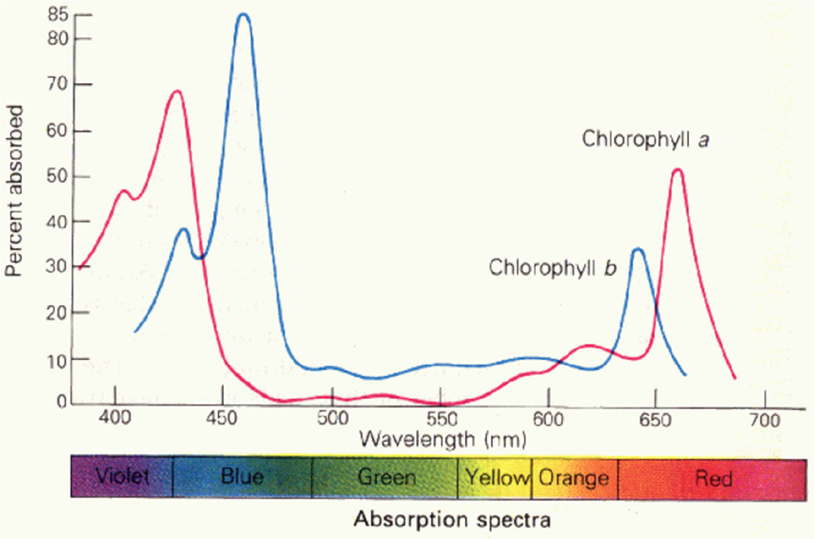

Two factors should be taken into account when considering the effect of roadway lighting on plants: the light level and the output spectral distribution of the light source (the wavelength composition of the produced light). The spectral distribution is of interest because photosynthetic sensitivity is dependent upon wavelength; both chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b exhibit higher activities in the lower (blue) and higher (red) wavelength ranges (Figure 4). This means that sources that output light in these wavelength regions are more likely to impact photosynthesis.

Photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) is the measurement of the total amount of PAR that is produced by the light source each second. PPFD for a light source can be calculated if the spectral power distribution of the light source is known (Ashdown, 2016). If Wrel (λ) is the relative spectral power distribution of the light source and V (λ) is the luminous efficiency function at wavelength λ, then t*he spectral radiant flux (Φ (λ)) incident on plants can be calculated as follows:

| Φ (λ)/lumen = [Wrel (λ)] / [683 * Σ (400-700) [V (λ) Wrel (λ) Δλ]] | (Equation 1) |

From this, the photosynthetic photon flux (PPF) per nm in micromoles per second per nm can be calculated as follows:

| PPF /nm = (10-3) * [λ * Φ (λ)] / (Na * h * c) | (Equation 2) |

where

- Na = Avogadro’s constant, 6.023 × 1023

- h = Planck’s constant (6.626 × 10–34 joule-seconds)

- c = speed of light, 2.998 × 108 m/s

- λ = wavelength in meters

The PPF per lumen for the given light source can be obtained by summing over the wavelength range of 400 to 700 nm:

| PPF = 8.359 * 10-3 * Σ (400-700) [λ * Φ (λ) * Δλ] | (Equation 3) |

The unit of PPF is micromoles per second (μmol/s) per lumen and all the photons are weighted equally from 400 to 700 nm, irrespective of the photosynthetic response. PPFD is the summation of the all of the photons falling on a surface for a given time and has units of mol/(sec-m2). HPS lighting typically has a PPFD of 11.7 μmol/sec-m2 per lm while a 4000 K LED PPFD might be 14.2 μmol/sec-m2 per lx (CIE, 2004). Based on PAR, a 4000 K LED could impact the plant more.

Photoperiodicity and Photomorphogenesis of Plants

Outside of photosynthesis, there are other effects of lighting on plants and many of these effects have been heavily documented. Plants such as soybeans and rice require a dark cycle to begin reproductive development and are significantly affected by light trespass from roadway lighting. The phenomenon in plants that requires darkness to mature is called photoperiod sensitivity and is the mechanism by which certain chemicals in the plant are converted from an inactive state to an active state to induce flowering or maturity. Photoperiodicity and photomorphogenesis are two aspects of photoperiod sensitivity. Photoperiodicity is the variation in response of a plant to the 24-hour day/night cycle in terms of reproduction or growth and is also referred to as circadian rhythm. Photomorphogenesis is plant development controlled by the spectral content of the light. The photoperiodicity and photomorphogenesis in plants are driven primarily by two photoreceptors: phytochrome and cryptochrome.

Phytochromes are plant photoreceptors that are part of the circadian regulation in plants and have the most influence on photomorphology. These receptors are sensitive to longer wavelengths in the red and infrared range, phytochrome has two isoforms that exhibit two different photochromicities and change photochromicity upon light absorption. The ground state (PR) has a narrow absorption with a peak at 650–670 nm (Devlin, 1969). Absorption of red light transforms the phytochrome to the PFR state, which has a peak absorption in the far red and near infrared, most sensitive to the range of 705–740 nm, with a much broader absorption that partially overlaps the PR range (Devlin, 1969).

Cryptochromes are flavoprotiens that act as another photoreceptor in plants. Cryptochromes absorb in the blue range with peaks near 450 nm and UV with peaks near 380 nm. Cryptochromes seem to partially regulate growth and circadian clocks in certain conditions, such as exposure to light with low red spectral content (Pedmale et al., 2016).

These plant species that have photoperiodicity impacts and need a dark cycle to begin reproductive development and are significantly affected by light trespass from roadway lighting. Stray light from roadway lighting fixtures could keep the plants in a vegetative state longer by rendering the flowering/reproductive mechanisms inactive (Brown Jasa, 1997). One of the earliest studies that reported the relationship between length of day and time of flowering for the soybean was conducted by Garner and

Allard (1920). They reported that, in the absence of a suitable length of day, the plant could go into a vegetative state, leading to gigantism.

Farm Crop Considerations

The impact of roadway lighting on farm crops is of particular interest due to the proximity of the field to the roadway and importance of these crops in the world food supply.

Two studies reported that artificial lights significantly affected the growth and maturity of the soybean (Briggs, 2006) and maize crops alongside roadways (Sinnadurai, 1981). Species that are more sensitive to the length of the day are significantly affected (fewer flower heads) by artificial lights that simulate roadway lighting (Bennie et al., 2015; Kostuik et al., 2014). Studies conducted in China have also shown that streetlights delay the maturity of the soybean in the summer and decrease yield (Zong-Ming, 2007).

Palmer (Palmer et al., 2017) found that roadway lighting of levels higher than 1.9 lux trespassing into the field hindered plant reproduction and led the plants to grow significantly taller than the plants that allowed for a dark period. These plants also had a lower seed yield.

Exposure

The specifics of the light impacts investigated on soybeans show the importance of the light source exposure. Lawrence and Fehr (1981) reported that plants exposed to light treatments every night experienced more delayed reproductive development than those exposed to light treatments every other night. Nissly et al. (1981) exposed several hundred strains of soybean to natural day length and an extended photoperiod of continuous 5-hour nighttime interruption. The soybean strains that were exposed to the extended nighttime photoperiod experienced a delay in flowering.

Spectrum

The spectrum of the light source also plays a significant role in the reproductive developments of plants. Artificial light elicited enhanced or suppressed growth depending on the plant species. This response was greatest in light sources with higher amounts of red lights and a higher red/far-red ratio, such as those used in conventional roadway lighting types (HPS) (Cathey and Campbell, 1975a, 1975b). Parker et al. (1946) first studied the spectra that prevented the flowering of soybean plants and reported that the wavelengths between 600 and 680 nm effectively prevented flowering. This prevention of flowering ends occurred at the red end of the visible spectrum (~720 nm; Figure 5). The phenomenon of the red spectrum preventing flowering in soybean plants was also reported by Downs (1956), who also suggested the effects of the red spectrum on the flowering of soybean plants could be reversed by brief exposures (2 to 5 minutes) to the far-red spectrum (> 735 nm). Han et al. (2006) also reported that the soybean flowering responses to the red spectrum (658 nm) were reversible by far-red spectrum (730 nm) exposure.

As previously mentioned, HPS lights are popular for road lighting because of their luminous efficiencies. The HPS spectrum has very little blue content that could cause undesirable morphological responses, such as stem elongation, in soybean plants. Wheeler et al. (1991) reported that HPS light sources that have lower blue light content may result in shorter stems. In that study, soybean plants were grown in the presence and absence of HPS lights with and without the presence of blue content. Total photosynthetic photon flux was maintained at 300 or 500 μmol/m2/s. The results of this study showed that the phenomenon of elongated stems in the presence of HPS lighting could be prevented by adding blue light to the spectrum of the light source (up to 30 μmol/m2/s; Figure 6). The Wheeler et al. (1991) study also found that plant reproductive development is affected by HPS light sources. Although the plants in that study—which were exposed to blue light—did not have elongated stems, it remains to be seen whether blue light could also affect later stages of plant growth and reproductive development. A different study showed that cool white fluorescent light could also result in a delay in the maturity of the soybean (Buzzell, 1971).

Recently, a study conducted by Cope and Bugbee (2013) examined the effect of three colors of LEDs (different levels of blue content in the light spectrum) on the growth and development of the soybean. The results showed that although the blue light did not affect the plant’s total dry weight, it did affect the plant’s development. Similar to the results of Parker et al. (1946), LEDs with higher blue content were found to result in soybean plants with shorter stems (Figure 7). The biggest differences in plant development were observed in low-light conditions (PPF = 200 μmol/m2/s). The results of the study showed that the amount of blue content in light required to cause an effect could depend on the plant’s age, and that light quality and level could significantly affect a plant’s growth and development.

Mitigation Approaches

Both traffic safety researchers and conservation scientists identify four key pathways to control unintended impacts of lighting, once lighting is deemed to be warranted. These are the control of light direction, intensity, spectrum, and duration (Gaston et al., 2012; Longcore and Rich, 2017). Each of these approaches may be useful in mitigating the consequences of increased radiance, irradiance, or both.

Table 1. Literature review findings to reduce the negative impacts of light on wildlife.

| Strategy | Lessons from Literature Review | |

| 1 | [Spectrum] Avoid ultraviolet |

Avoid using sources with ultraviolet near animal habitats (Hart, 2001) Ultraviolet will attract insects and consequently some bat species (Donners et al., 2018; Lewanzik and Voigt, 2017) LEDs attract fewer insects compared to other sources (Eisenbeis and Eick, 2011; Justice and Justice, 2016; Poiani et al., 2015; Wakefield et al., 2018; Wakefield et al., 2016). |

| 2 | [Spectrum] Avoid light with short wavelength |

Green, blue, and white light will reduce moth activity (van Langevelde et al., 2017) Blue light is more attractive to moths (Cowan and Gries, 2009) Amber light will be less disruptive for birds (Aulsebrook et al., 2020) White, blue, and green attract more birds (Rebke et al., 2019; Xuebing et al., 2020) Warm light will attract fewer bats (Fure, 2012) Warm light (2700-3000K) will attract fewer insects (van Langevelde et al., 2011a) |

| 3 | [Intensity] Avoid light with high intensity |

High-intensity light attracts more moths (Cowan and Gries, 2009) The light level of 3.6 lux or less has a lower negative impact on bats (Stone et al., 2012) Increasing light intensity will increase bat’s attraction (Bolliger et al., 2020) Light with high intensity attracts more insects (Bolliger et al., 2020) Fireflies prefer the light intensity of 0.2 lux or less (Hagen and Viviani, 2009) |

| 4 | [Direction/Duration] Use appropriate fixture |

Flashing light will attract fewer birds (Gehring et al., 2009) Using low-height pavement lighting will attract fewer turtles (Bertolotti and Salmon, 2005) |

| 5 | [Warrant] Stay as far as possible from wildlife habitat |

Moth will be attracted to light sources in a radius of 25–130 meters of their habitat (Degen et al., 2016; Frank, 2006) Lights should not be close to birds’ habitat (de Jong et al., 2016) |

Direction

Direct glare impacts are most easily mitigated through light shielding so that light is directed toward the roadway surface or adjacent sidewalk. For impacts from scattered light on astronomical observation, shielding is a primary tool and limiting uplight is often considered to be an adequate mitigation. Two situations limit the effectiveness of shielding. First, when lights are shielded downward but still extend direct glare into sensitive habitats, such as roadside habitats lower than the road surface (e.g., wetlands, rivers) and especially on bridges. Second, when roadway lighting is installed in areas with low ambient lighting, the contrast with dark surroundings is high and even reflected light off the roadway is sufficient to attract or repel wildlife, even if they are not exposed to direct glare. Entomologists have long been

familiar with this phenomenon, as observed when modestly illuminated locations in remote areas become overwhelmed with phototactic insects.

Intensity

Lower intensity of any lamp will always have a reduced influence on flora and fauna. Reduction in intensity is therefore a preferred approach to minimize impacts from roadway installations. The presumption should always be that the minimum intensity needed for the objective of the lighting installation is preferable. It is possible to summarize illumination thresholds for specific wildlife responses (Figure 8), and even low levels of sky glow exceed light thresholds for a wide range of wildlife responses. It is therefore incumbent on transportation safety and lighting researchers to demonstrate the minimum light levels that are necessary to achieve intended safety goals. Thresholds for wildlife impacts can be used to then evaluate the extent of impacts from such systems, the areas exposed to unnatural illumination, and approaches for mitigation.

Spectrum

Spectrum and intensity are intertwined in the assessment and mitigation of impacts from roadway lighting. Because of the range of photoreceptors in organisms, one light source emitting the same number of photons could be perceived as having different intensity by two organisms. Because roadway safety lighting needs to be seen by humans, the question is how to provide the needed brightness for humans

(usually measured in lux; for human photopic vision) while reducing the apparent brightness and biological relevancy for other species (see Longcore et al., 2015; Longcore et al., 2018a).

Given that jurisdictions are likely to continue to meet minimum recommended lighting levels on roadways, the goal from a mitigation perspective is to encourage meeting those goals using lamps with an output spectrum that will have reduced impacts. Such decisions would also be influenced by research that can conclusively show the influence of spectrum on detection and avoidance of obstructions by drivers.

On the wildlife side of this equation, the preponderance of evidence indicates a need to avoid shorter wavelengths of light (Longcore et al., 2018a). First, lights with high blue light emissions will increase scattering in the atmosphere and increase sky glow and resulting impacts in nearby habitats (Falchi et al., 2011). Ultraviolet light, being invisible to humans, should be avoided entirely. Unless designed for that purpose, LEDs do not emit ultraviolet and are therefore less attractive to insects (Wakefield et al., 2018). This pattern has been shown in comparisons of many lamp types (Figure 9).

Eisenbeis and Eick (2011) compared how attractive different lamp types were to insects in Germany. The authors used cold-white LED, halogen spotlight, neutral-white LED, HPS vapor, mercury vapor, and metal halide sources. The results showed that sources that emit less ultraviolet light (UV) will attract fewer insects (such as LEDs). Among LEDs, warmer sources were less attractive than colder (higher CCT) sources.

Longcore et al. (2018a) compiled spectral response curves for insects, sea turtles, juvenile salmon, and seabirds to demonstrate an approach to assess the potential effects of meeting illumination standards with lamps of different spectral composition. The results indicated a high correlation between wildlife impact and prevalence of blue light; wildlife impact increased significantly with CCT. Lamps with the least blue light (e.g., low pressure sodium) had the lowest composite impact scores, and when color rendering index was considered to balance visual performance, the lamps with the least wildlife impact while maintaining color rendering were phosphor-coated amber LEDs and blue-filtered warm white LEDs (Figure 10).

This research is limited by the number of species response curves that were included and further compilation of visual responses by taxonomic group and associated behavioral observations are needed to confirm and refine these results.

Duration

Although roadway lighting is typically thought of as being on from dusk to dawn, nothing is stopping other light timing strategies that could maintain safety and reduce adverse impacts. For example, nearly 20 years ago, Dutch officials developed a bi-level lighting system for roads through sensitive grassland habitats in which area lighting operated until 11 p.m., at which point dim lights affixed two-thirds of the way up the poles were illuminated for orientation. A subsequent study confirmed traffic safety was not adversely impacted (De Molenaar et al., 2006). This scheme is an example of “part-night lighting,” which has been subsequently suggested and researched as a mitigation measure for impacts to wildlife. Research suggests that limiting the time of illumination can reduce impacts in general, but it may not be sufficient to protect sensitive species (Azam et al., 2015). Animal activity is not evenly spaced within the nighttime hours and a significant amount of activity occurs during crepuscular hours. Species that exploit light conditions during dusk would not be benefited by part-night lighting, but certainly overall some species would benefit, and such strategies should be encouraged where possible.

Lighting Regulations and Guidelines

In this section, we present lighting regulations and case studies that have been used by different U.S. states and countries to mitigate the negative impacts of lighting on wildlife.

AASHTO Roadway Lighting Design Guide

The seventh edition of the AASHTO Roadway Lighting Design Guide, published in October 2018, suggests considering environmental issues when designing lighting masterplans. It also suggests paying attention to the function and purpose of lighting before starting to design. Additionally, considering different light zones introduced by the Illuminating Engineering Society (IES), backlight, uplight, and glare to help evaluate the optical performance of luminaires can help reduce skyglow and light trespass is

suggested. Except for the question of process, none of the guidelines are specifically relevant to considerations involving wildlife.

Hawaii State Lighting Regulations

In 2012, due to Act 161 (“Act 161,” 2012), Session Laws of Hawaii 2009, all light fixtures emitting more than 3000 lumens had to be fully shielded to protect the night sky and associated cultural, natural, and other values. Lamps are also to have a CCT of 3800 K or less. Billboards are banned except at military sites. Based on Act 161 section 2015A-71, lighting for decoration or aesthetic purposes is not allowed when shoreline and ocean are directly or indirectly illuminated.

State of Florida Roadway Lighting Regulations

To protect animals, especially shore animals such as turtles, the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT, 2016) recommends following the FHWA’s adaptive lighting guidelines (Gibbons et al., 2014) and the AASHTO Lighting Design Guide. Maintaining a light ratio (minimum to average illumination) of 1:3 or 1:4 and maximum to minimum uniformity of 10:1 is also essential to let the eye of the driver to adjust to the light level.

Australian Government Roadway Lighting Regulation

Based on the Australian Government Department of Environment and Energy’s lighting regulations, outside building lights should be examined to control their potential effect on wildlife (Pendoley et al., 2019). When outdoor lighting is needed, the Best Practice Lighting design (Figure 11 and Figure 12) should be used.

“Best practice lighting design incorporates the following design principles:

- Start with natural darkness and only add light for specific purposes.

- Use adaptive light controls to manage light timing, intensity, and color.

- Light only the object or area intended – keep lights close to the ground, directed, and shielded to avoid the light spill.

- Use the lowest intensity lighting appropriate for the task.

- Use non-reflective, dark-colored surfaces.

- Use lights with reduced or filtered blue, violet, and UV wavelengths (Pendoley et al., 2019).

Case Study 1: Gorgon Liquefied Natural Gas Plant on Barrow Island, Western Australia

One example of mitigating the negative impacts of artificial light on the environment can be found in Chevron-Australia Gorgon Project, which is a big natural gas project in Western Australia. The plant was built near an important turtle nesting beach, but lighting was also required on the site to ensure personnel safety. The lighting plan’s main goal was to reduce glow and eliminate direct light spill on the beaches. The following strategies were implemented to achieve both goals:

- using directional and shielded fixtures,

- mounting the light fixtures as low as possible,

- using louvered lighting on bollards,

- using adaptive automated lighting, and

- using black-out blinds on building windows (Pendoley et al., 2019).

Case Study 2: Philip Island

This island is one of the largest habitats for migratory Short-tailed Shearwaters (Ardenna tenuirostris). The fledglings are attracted to the shore lights and become disoriented and vulnerable to collisions. To prevent this, during the fledgling period, lights are turned off. The speed limit in the region has also decreased and the use of warning signals employed to further reduce collisions (Pendoley et al., 2019).

Lighting Regulation in the Netherlands

Based on a study in 2017, bat species are disturbed by light sources and are impacted differently by different spectra. White and green light are more disturbing compared to red. As a result, to mitigate the negative impacts of light on bats, red light should be used near their habitats (Spoelstra et al., 2017). The Zuidhoek-Nieuwkoop Dutch community, which is one of the rare habitats of many animals and plant species, has used red lights from Signify (formerly known as Philips Lighting) in one of their streets (Figure 13). This is also the first town in the world that has used smart LED lights to protect wildlife (Spaen, 2019)—Signify’s Interact City connected LED lighting system can save up to 70% in energy usage and enables the city authority to dim or turn off the lights during the night.

Ameland, one of the Netherlands’ northern islands has also installed white-green LED instead of white lights (Figure 14) so that fewer birds will be attracted to the light source. Fixtures are also equipped with motion sensors that dim the light when no one is around (Signify, 2017).

The Hertogenbosch to Vlijmen biking route also uses dynamic light to both provide safety and protect the wildlife (Figure 15). The route has LED sources with sensors that can detect human presence with heat and light at the next fixture. The lights’ turn on/off timing is based on the Netherlands average trail bike speed, which is around 16 km/hr (Bicycledutch, 2018).

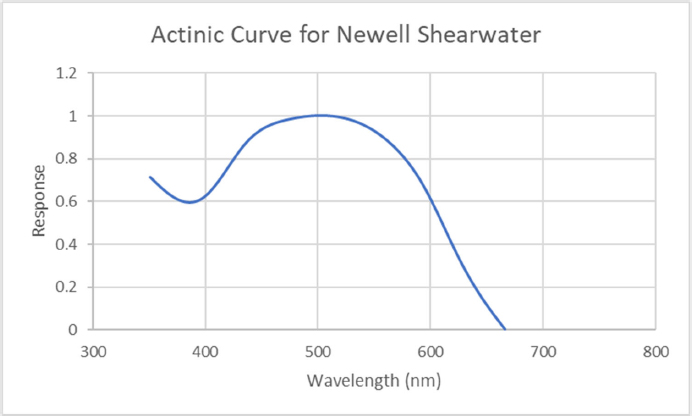

Spectral Response Curves

In this section of the literature review, some studies on animal spectral response curves are introduced. Visual spectral charts show the sensitivity of photoreceptors on a specific wavelength. Thus, they can be an effective tool for predicting animal behavior under different light sources. Some of the available studies are mentioned here as examples.

Chromatic vision is an important part of insect ecology. It helps insects find a suitable habitat, their food, and to mate (Huang et al., 2014; Song and Lee, 2018). Insects have compound eyes that consist of repetitive visual units called ommatidia. Each of these units has eight to nine photoreceptors or retinular cells comprising densely packed visual pigments that absorb light (Figure 16). Most insects have UV, blue, and green receptors with a peak around 340, 440, and 530 nm (Briscoe, 2000; Song and Lee, 2018). There are differences among different species’ photoreceptors as well. As an example, cockroach Periplaneta Americana’s photoreceptor can only sense UV and green light, and butterfly Papilio Xuthus can sense UV, blue, violet, green, and red light (Kelber et al., 2003).

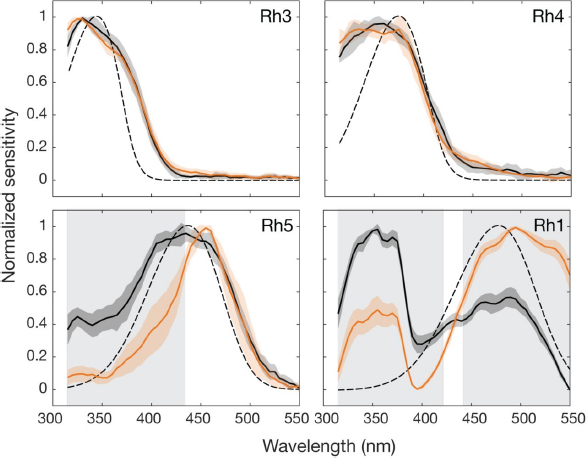

Drosophila’s (common fruit fly) compound eye consists of approximately 750 ommatidia (Wolff, 1993), each having a bundle of eight photoreceptor cells and 12 auxiliary cells. Each photoreceptor cell has a “rhabdomere, a microvillar structure that contains the visual pigment and serves as the compartment for visual transduction. The rhabdomeres are arranged concentrically with the six peripheral rhabdomeres of the R1–R6 cells surrounding one central rhabdomere formed by the R7 or R8 cells in the distal or proximal portion of the ommatidium, respectively” (Salcedo et al., 1999). The rhabdomeres of the R1–R6 photoreceptor cells hold the major visual pigment of the insect eye, the blue-absorbing Rh1 rhodopsin. The R7 cells express Rh3 or Rh4, which is the UV absorbing visual pigment. R8 cells express one of Rh5 or Rh6, and R7 and R8 express Rh3 cells, while Rh2 encodes a violet-absorbing pigment (Feiler et al., 1988; Salcedo et al., 1999).

In a study by Salcedo et al.(1999), researchers obtained electroretinogram recordings from white-eyed flies using glass microelectrodes. A xenon arc lamp was used to stimulate the fly’s eyes. The lamp had different filters for different light intensities and wavelengths. They calculated light intensity with a “calibrated silicon photodiode (model 71883; Oriel) and an optical power meter (OPM model 70310; Oriel).” Spectral sensitivity was calculated using the modified version of the voltage-clamp method developed by Franceschini (1984). Figure 17 shows the spectral sensitivity of Rh1, Rh5, and Rh6. The Rh1 spectral chart shows the peak sensitivity in the blue and UV parts of the spectrum. The microspectrophotometry (MSP) charts are “calculated from the difference spectra recorded from the MSP and detergent-extracted pigments.” The bottom left chart shows the peak sensitivity of Rh5 and Rh6 with “Rh5 have a prominent peak of sensitivity at ∼440 nm, whereas flies expressing Rh6 have a prominent peak at ∼510 nm” (Salcedo et al., 1999).

Drosophila melanogaster’s spectral sensitivity curve (Sharkey et al., 2020) in Figure 18 shows normalized spectral sensitivity for the orange-eye (orange lines) and red-eye (black eyes) flies.

Figure 19 shows the spectral sensitivity of Asian swallow tail butterfly (Papilio xuthus) photoreceptors. This insect uses color vision when foraging, and has eight photoreceptors on its retina: the “UV; V, Violet; NB, Narrow blue; SG, Single green; R, red; WB, Wide blue; DG, Double green; and BB, Broadband” (Koshitaka et al., 2008; Osorio and Vorobyev, 2008), which are (A) Narrowband receptors; (B) Broadband

receptors. Koshitaka et al. (Koshitaka et al., 2008) used newly eclosed insects from a Japanese female swallow tail butterfly, and a 500 W xenon arc lamp with a monochromator and filters. These tests were originally done to prove tetrachromacy in invertebrates. The study results showed that the color vision of the swallow tail butterfly also includes UV wavelengths. Many other studies confirm that insects can see UV (Menzel and Backhaus, 1989).

Figure 20 compares the spectral sensitivity of humans, honeybees, swallowtail butterflies, and fruit flies, showing animal photoreceptors to view different chromes.

In a study on the light sensitivity of pigeons, the results showed that pigeons’ visual system is very similar to that of humans (Blough, 1957). The data was obtained from three male pigeons using 15 wavelengths ranging from 380 mμ to 700 mμ. The maximum photopic spectral sensitivity was around 560–580 mμ and

for the scotopic was 500 mμ (which is close to human aphakic data). The pigeon eye has a duplex retina which consists of rods and cones. Thus, it is not surprising to see similarities in curves (Figure 21).

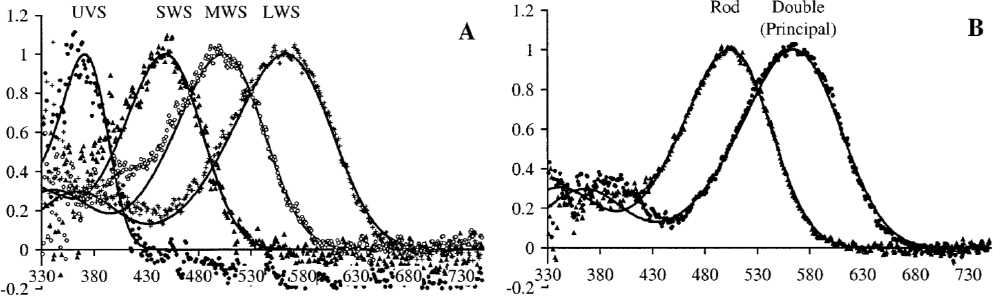

Another study on blue tit and blackbird spectral absorptance characteristics evaluated the effect of light on their visual systems. Their retinas consist of rods, double cones, and four spectrally distinctive single cones. For this study, researchers caught wild blue tits and blackbirds then analyzed the birds’ retina tissue using a microspectrophotometer (MSP). Blackbird rods contained rhodopsin with a mean λmax of 540 nm (Figure 22). The UVS single cone had a visual pigment similar to the blue tit’s, which was around 373 nm (mean λmax) (Figure 23). The following figures show the variations in visual pigments λmax in the two species (N. Hart et al., 2000).

Longcore et al. (2018b), the authors developed a method to predict the effect of different light source spectra on different types of organisms. The goal was to find light sources with a minimum harmful effect on wildlife (Figure 24). Based on the results, “filtered yellow‐green and amber LEDs are predicted to have lower effects on wildlife than high-pressure sodium lamps, while blue‐rich lighting (e.g., K ≥ 2200) would have greater effects.” Available response curves were used for estimating the effect of light sources on different wildlife groups (Figure 25).

The calculation method that was created can be used to evaluate the effect of source light source on any organism. The calculation can be repeated for any response curve or light source spectra (Longcore et al., 2018b). So, the effect of light sources on any available spectral chart in the literature can be predicted.

Gaps

The impact of a lighting system on various species is very hard to establish. To reduce or minimize any impact of the lighting system, there are four characteristics of the light exposure that can be controlled:

- Spectrum

- Light intensity

- Duration of exposure

- Timing of exposure

The gaps in research that have been identified as limitations to providing guidelines for the reduction in lighting impact are shown below:

- No metric for the evaluation of the impact of a lighting system on a given species or plants exists. With the variety of spectral responses for each species, the metric would have to be specific to each animal.

- An approach to comparing alternative lighting system designs and to no lighting configurations in terms of lighting impact does not exist.

- Limitations of measured lighting characteristics to ensure minimized impact on flora and fauna need to be established.

CHAPTER 2

Metric Calculation Method

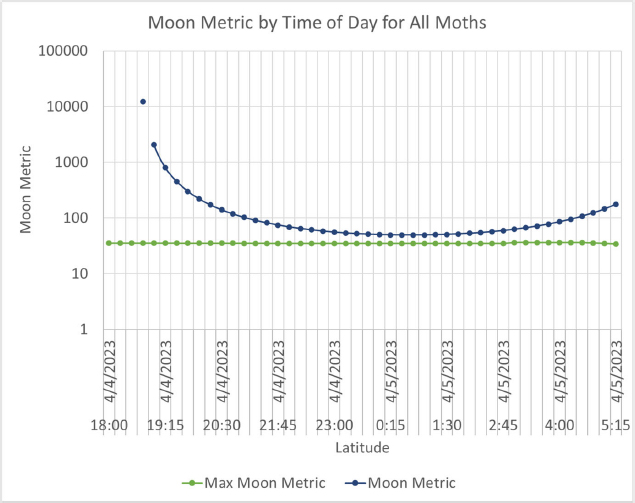

A proposed metric for the impact of nighttime lighting on an area is a comparison with naturally occurring light sources and conditions, of which the moon is the most dominant. For measurements of irradiance, the irradiance measured during different phases of the moon provides a basis for comparison with natural conditions.

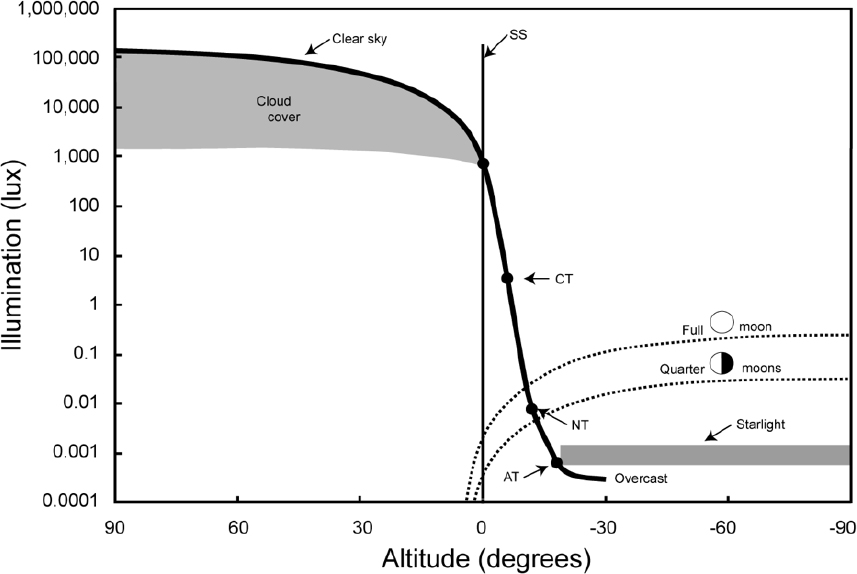

Comparison with natural values of both radiance and irradiance could be used to map distribution of potential impacts from new or replaced lighting systems. Zero impact is never a possibility because all roadway lighting meets standards that exceed moonlight by at least an order of magnitude, but such benchmarking to natural conditions could be used to evaluate the spatial extent of impacts of different levels (e.g., irradiance exceeding full moon, half moon, quarter moon) and the duration of those impacts.

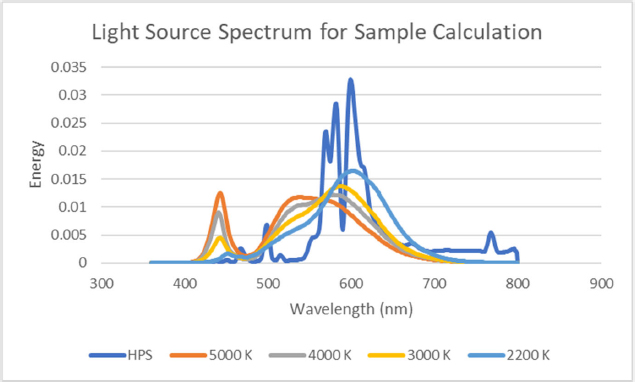

As highlighted, the impact of a lighting system on flora and fauna is based on two aspects of the lighting system: the spectrum of the light source and the intensity of the light source (the timing and duration can be developed from the impact of spectrum and intensity by integrating the impact of the intensity over the duration and comparing the timing to the time of the moon). These aspects can be considered as a dosage; thus, a lighting system with a higher intensity but a less reactive spectrum may be better than a dim lighting system with a more invasive spectrum.

Metric Formulation

Based on the work shown in (Longcore et al., 2018a), the proposed metric is the ratio of the impact of a lighting system on a given species to the impact from the moon on the same species. The proposed moon metric M is calculated as shown in Figure 26.

Here, the effective dosage of the light source on the species is calculated based on the integral of the spectral power distribution of the light source under consideration and the actinic response of the species under consideration, scaled by the illuminance from the design. This value is compared to the effective

dosage of the moon, where the spectrum of the moon and the illuminance of the moon are used. This moon metric is then the ratio of the dosage from the light source in a ratio with the dosage from the moon. It is notable that the moon metric is given based on a certain latitude, longitude, date, and time.

One of the important aspects of the moon metric is that it is linear with the design level of the lighting system. As the lighting level from the design is the numerator of the metric, an impact factor can be developed for each combination of species and light source spectrum. This impact factor would then be calculated using 1 as the lighting level. The calculated impact factor could then be considered as a normalized tool to compare the impact of spectrum on a given species.

The derivation of the impact factor would be as shown in Figure 27:

This impact factor uses the spectral impact of the moon but does not include the moon illuminance, which would still need to be calculated for the design comparison.

A generalized moon metric can be considered, which would be the maximum moon impact for a given latitude and longitude.

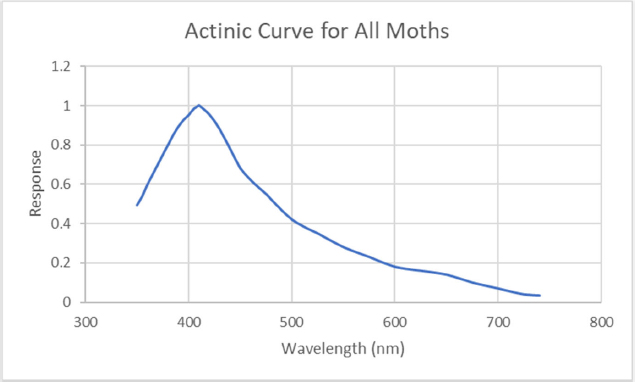

This calculation then requires the following:

- Actinic curves for a variety of species as well as a generalized sensitivity curve.

- A standard moon calculation, where the illuminance level from the moon can be calculated for a given date, time, latitude, and longitude as well as the maximum illuminance for a given latitude and longitude.

- A calculation of the lighting effects from the design under consideration.

Actinic Curve Cataloging

Use of spectrum to mitigate roadway lighting impacts on other species is a promising approach, as is only using the necessary amount of light for safety and directing it only on the roadway. Such “spectral tuning” has been investigated with the limited power distributions available with legacy lighting sources, and it is now being explored with the greater breadth of choices available with LEDs (Deichmann et al., 2021; Eisenbeis and Eick, 2011; Longcore et al., 2015; Longcore et al., 2018a; van Grunsven et al., 2014). This approach depends on the availability of actinic curves that describe the response of an organism to different wavelengths of light. Some have been long available, such as a description of the attraction of moths to light (Cleve, 1964), and considerable research on the sensitivity of animal visual systems was completed during the second half of the 20th century. Many of these results were not reported in digital format, so Longcore, under contract with the California Department of Transportation, compiled and digitized these curves for as many terrestrial wildlife species as could be located using an exhaustive search strategy (Longcore, 2023). These results were combined with a database also compiled of the peak sensitivity of each photoreceptor present in terrestrial wildlife species.

In the review of photoreceptors, 968 photopigments from 320 species, subspecies, or varieties were located. When plotted by taxonomic order, and sorted by the average peak sensitivity of all photoreceptors in the order, it is evident that arthropods (invertebrates with exoskeletons such as insects, spiders, and

scorpions) are more likely to be sensitive to shorter wavelengths, reaching into the ultraviolet, than are species with a spinal cord (mammals, reptiles, birds, amphibians) (Figure 28). Exceptions from within the chordates are rodents, bats, and snakes/lizards, each of which have ultraviolet vision.

In all, 175 spectral responses were digitized and standardized to a 0–1 range, consisting of different species, but also light and dark testing conditions for some species (Figure 29). The shift in sensitivity to shorter wavelengths seen in human vision (i.e., the Purkinje effect) is seen in the average of all species across all terrestrial wildlife (Figure 29). Most of the responses were from experiments that tested down to 420 nm and 70 nm below that into the ultraviolet range (Longcore, 2023). On average, the peak sensitivity for mammals was the longest (508 nm), followed by birds (503 nm), amphibians (499 nm), and insects (460 nm) (Figure 30). Note that this spectral response analysis does not consider any secondary effects where an impact on one species affects another species.

The catalog of actinic curves was complemented by a structured literature review on the effects of LEDs specifically on terrestrial wildlife (Longcore, 2023). Effects in many well-documented areas were summarized, but little evidence was found that suggested that there was anything specifically about light from LEDs that made it different from light from other sources, with the possible exception of flicker (Barroso et al., 2017; Inger et al., 2014). We therefore suggest that research on effects focus on the intensity, spectrum, duration, and distribution of the light itself, with awareness of emerging research on flicker from LEDs.

Development of the Standard Moon

The development of the moon metric must include the specification of a standard moon. Again, this would include the amount of light from the moon at different phases and the adoption of a standard moon

spectrum. These two criteria are critical to defining the metric and for the calculation of the metric in a design situation.

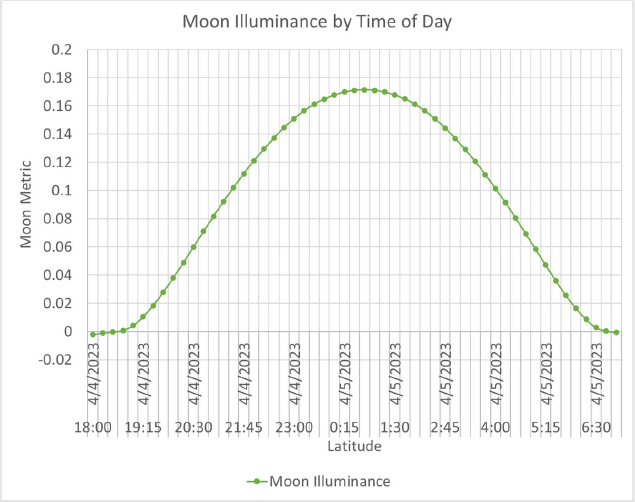

The maximum illuminance from the moon has been found to be approximately 0.4 lux (Brown, 1952; Krisciunas and Schaefer, 1991), but under most circumstances it does not exceed 0.1 lux (Kyba et al., 2017), as shown in Figure 31. It is noteworthy in this figure that the moon’s brightness depends both on the angle of altitude and the phase of the moon. There is also an impact of the weather and the cloud layers which reduce the light reaching the Earth however this is not included in the design metric as these are transient conditions.

Like the intensity, the standard spectrum has been published (shown in Figure 33), but the same potential impacts of moon phase and altitude may impact this measure. Similarly, the spectrum could be impacted by the latitude of the observer as well. The research will determine if the standard moon is adjusted for latitude, as this allows for comparison of impacts on certain species but will complicate the development of the metric.

There are two aspects of the moon that need to be considered in this evaluation; the first is the moon spectrum, and the second is the illuminance from the moon at the location of interest. Both are considered in the developed model of a standard moon.

Spectrum of the Moon

The spectrum of the moon is very similar to the spectrum of daylight; this obvious relationship is due to the light from the moon being daylight reflected off the regolith (surface dust on the moon). This reflectance, shown in Figure 32, shows an increasing reflectance from ultraviolet to infrared and is consistent across all samples brought to Earth from the Apollo missions (Izawa et al., 2014),

The spectrum of the reflected light from the moon has been measured by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (Cramer et al., 2013).. The spectrum for the visible wavelengths is shown in Figure 33.

The spectrum considered for the moon model is irradiance, meaning that it is unweighted by the spectral sensitivity of humans and can be weighted by any spectral response. For use in the moon model, the spectrum considered was scaled to be equivalent to an illuminance at the Earth’s surface of 0.215 lux, which is the illuminance level on Earth from the full moon positioned at apogee.

Illuminance from the Moon

The amount of light falling on the Earth at any point is a complex calculation. The moon has an elliptical plane that is 5.6 degrees slanted from the Earth’s elliptical plane, as shown in Figure 34. Here, the geometry of the moon’s plane, the Earth’s tilt of 23.44 degrees, and the geometry of the moon revolving around the Earth means that the moon’s appearance in the sky and its location varies significantly from day to day. Similarly, as the moon rotates around the Earth, the percentage of the illuminated portion of the moon changes. Typically known as the phase of the moon, the illuminated portion can vary from 100% at a full moon to 0% at a new moon.

Following the methodology presented in (Austin et al., 1976) the following steps are undertaken to calculate the light from the moon:

- Determine the position of the moon in the sky in terms of the angle of elevation and the angle from due north.

- Calculate the phase of the moon based on the date of interest. If no specific date is used, a standard level of illuminance for a full moon at parallax is used (0.251 lux).

- Calculate the change in the illuminance due to distance from the moon to the Earth. As the moon’s orbit is elliptical, the distance from the moon to the Earth will vary from 226,000 mi (363,300 km) at perigee to 251,000 mi (405,500 km) at apogee.

- Calculate an adjustment for the attenuation of the moon’s radiation due to the atmosphere.

- Calculate the vertical and horizontal components of the illumination based on the moon’s angle of elevation.

The irradiance from the moon is then based on the equation shown in Figure 35. Several mathematical models of the moon location in the sky have been developed for the model presented here, and the moon’s characteristics have been developed based on the method in (Jean, 2005; Lawrence, 2018; Reingold and Dershowitz, 2018).

Position of the Moon in the Sky

The position of the moon relative to the Earth is calculated based on the date of interest. This date is converted to a Julian date, which is based on the moon month. To start with, a benchmark time is used where the position of the moon at a given time has been determined and is the base point for all calculations. The moon’s position at a given date is then determined based on the number of Julian months that have passed since the known benchmark time. The same calculation methodology is used to calculate the position of the sun relative to the Earth. Once the position of the moon and the sun have been determined relative to the Earth, the latitude and longitude of the location of interest are then used to calculate the specific moon location in terms of (a) the angle of elevation of the moon and sun and (b) the azimuth of the moon and sun (i.e., the number of degrees from north that the sun and moon appear).

For the calculation of the moon metric, if a specific location is not being considered, the latitude of interest can be used to calculate the maximum elevation angle of the moon and to provide a maximum lighting level.

Percent Illuminance of the Moon

As the moon reflects light from the sun, the illuminance from the moon is proportional to the amount of the moon that is in shadow. As the moon revolves around the Earth, the phase of the moon changes, which represents the position of the moon with respect to the sun. In a full moon, the moon is directly opposite the sun with respect to the Earth and there is no shadow visible from the Earth. For a half moon, the moon is 90 degrees from the sun, and half of the moon is in shadow; finally, in a new moon, the moon is between the Earth and the sun and is totally in shadow.

For the moon model, we have used the Julian date, the phase of the moon, and the percentage of shadow. This value, the phase factor, is then used to scale the illuminance from the moon as a percentage of the full moon. If no specific date is used in the calculation, the phase factor is assumed to be 1, representing a full moon.

Distance Adjustment

As the moon is in an elliptical orbit, the distance from the Earth changes. At apogee, the moon is the farthest from the Earth, and at perigee, the Earth is closest to the moon. At the 90-degree points from apogee and perigee are points called parallax, which is the midpoint of the distance of the moon to the Earth.

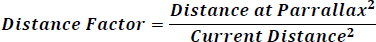

The distance the moon is from the Earth varies from at apogee to at perigee. For a specific date and time, the distance from the moon to the Earth can be calculated. The inverse square law is applied to adjust for the distance changes as compared to the distance at parallax (which is the base condition for the moon illuminance of 0.251 lux). This distance factor is then calculated as shown in Figure 36.

Atmospheric Attenuation of the Moon Radiation

As the radiation from the moon passes through the atmosphere, it is attenuated due to the photons from the sun colliding with the atmospheric particles. The greater the number of collisions, the greater the attenuation of the radiation. This attenuation is directly proportional to the elevation of the moon. Lower elevations force the radiation to travel through the atmosphere a longer distance, which creates greater attenuation.

For the moon model attenuation calculation, data from stellar attenuation is used to calculate an attenuation factor according to the angle of elevation based on the method from (Austin et al., 1976). This relationship is shown in Figure 37. The attenuation from the Earth’s atmosphere is then calculated from this model as a percentage of the total irradiance.

Horizontal and Vertical Illuminance from the Moon

The final aspect of the illuminance from the moon is to convert the moon illuminance, which is an overall irradiance found on the Earth’s surface, to horizontal and vertical illuminance from the moon using a cosine relationship with the angle of elevation from the moon.

Calculation of the Moon Metric

The final moon metric for a species of interest is the ratio of the impact of a light source at a given design level as compared to the impact of the moon on the same species. This is calculated first by weighting the spectrum of the light source of interest by the actinic curve of the species of interest, which is then scaled by the design value. The next calculation is the impact of the moon based on the irradiance from the moon scaled to the latitude, longitude, and time of interest, which is weighted by the actinic curve for any species of interest. This follows the equations shown in Figure 26.

As the latitude, longitude, and specific time may not be an important consideration for use in a design metric, the standard illuminance of the full moon at parallax for a given latitude can be used for the moon impact. This would be considered the maximum illuminance of the moon on the Earth’s surface.

Sample Calculations

A sample calculation has been prepared to demonstrate the results of this moon calculation. The inputs to the calculation are:

Location: Blacksburg Virginia, Latitude and Longitude (37.22653, -80.4139)

GMT Adjustment: -4 (This represents the number of hours from Greenwich Mean Time)

Date of Interest: January 10, 2023

The results of the calculation for the sun and moon position as well as the irradiance and illuminance are:

| Moon Elevation (Degrees) | 41.4 | ||

| Moon Elongation | 115.3 | ||

| Distance (km) | 390292 | ||

| %Illumination | 71.5 | ||

| Diameter | 30.94 | ||

| Moon Azimuth (Degrees) | 252.2 | ||

| Sun Elevation (Degrees) | -66.9 | ||

| Sun Azimuth (Degrees) | 301.9 | ||

| Maximum | Time-Based | ||

| Irradiance | 0.00118 | 0.00044 | |

| Illuminance | 0.238 | 0.089 |

A negative elevation angle indicates that the sun or the moon are below the horizon.

The maximum irradiance and illuminance measures are taken as the maximum levels from the moon for the given position, meaning that the calculation is performed assuming a full moon at perigee and at the maximum elevation possible for the location. The time-based calculations are for the time specified in the input variables.

The next step in the calculation is to define the impact of the moon in a given species. For the sample calculation, three actinic curves were selected: human (V Lambda), Ascalaphus macaronius, and Calliphora (dark adapted). These curves are shown in Figure 38.

For the sample calculation, a 4,000 K LED light source was selected with the following characteristics and a spectral power distribution shown in Figure 39:

| x | 0.4 |

| y | 0.4409 | |

| Spectral Flux | 681.3893668 | |

| CCT | 3702 | |

| Scotopic | 945.635539 | |

| S/P | 1.387804954 |

For the calculation, a design metric of 5 lux was selected. The resulting moon calculation for the three selected species appears in Table 2.

Table 2. Sample calculation results.

| Actinic Curve | Ascalaphus macaronius | Calliphora (dark adapted) | V Lambda |

|---|---|---|---|

| Response Under Test | 0.00104 | 0.81042 | 0.99762 |

| Response Scaled to Lighting Design | 0.00001 | 0.00595 | 0.00073 |

| Maximum | |||

| Moon Response | 0.00001 | 0.00041 | 0.00035 |

| Moon Metric | 1 | 14.512 | 20.914 |

| Time-Based | |||

| Moon Response | 0.00001 | 0.00015 | 0.00013 |

| Moon Metric | 1 | 39.667 | 56.308 |

The sample calculation results show the impact of a 5-lux lighting design as compared to that of the moon. For the date and time selected, the impact on humans is 56 times that of the moon and is 21 times that of the maximum moon impact. For Ascalaphus macaronius, the impact is equivalent to that of the moon. This is an important consideration, as the actinic response of this species is all in the ultraviolet range