Gaps and Emerging Technologies in the Application of Solid-State Roadway Lighting (2024)

Chapter: 4 Characterization of the Effects of Roadway Lighting on Fauna and Flora

CHAPTER 4

Characterization of the Effects of Roadway Lighting on Fauna and Flora

Roadway engineers have focused significant attention on the effects of roadway lighting and vehicle headlamps on accident occurrence and outcomes. As discussed through the consideration of CMFs, it is unsurprising that roadway lighting is usually perceived by transportation engineers as an uncontroversial and unproblematic benefit to roadway design. Consequently, roadways are cumulatively the most visible feature of cities from space at night (Kinzey et al., 2017; Kuechly et al., 2012; Luginbuhl et al., 2009).

Construction and upgrades to transportation infrastructure such as lighting are, however, subject to environmental review, such as under the federal law (National Environmental Policy Act) and similar state-level laws, which require identification, disclosure, and mitigation of significant adverse impacts on the environment. In this regard, light at night associated with roadways may be seen as a pollutant, adversely impacting flora (Palmer et al., 2017) and fauna (Bertolotti and Salmon, 2005; Blackwell et al., 2015; Gaston and Holt, 2018). Transportation planners and engineers are faced with the challenge of reconciling the benefits of roadway lighting with the rapidly growing literature on the effects of artificial light at night on species and ecosystems (Gaston et al., 2013; Gaston et al., 2012; Gaston et al., 2014; Hölker et al., 2010; Longcore and Rich, 2004; Rich and Longcore, 2006; Schmiedel, 2001; Verheijen, 1958), when that literature is not organized specifically around roadway or vehicle lighting (but see Bertolotti and Salmon, 2005; Blackwell et al., 2015; Gaston and Holt, 2018)). Sometimes studies are explicitly aimed at and about roadways (De Molenaar et al., 2006). Other times roadway lamps are used to create light conditions for studies (Knop et al., 2017).

To address this growing awareness of the ecological impacts of roadway lighting and the need for guidelines for transportation engineers, we have undertaken a review of the literature on artificial light at nighttime and on ecosystems. We have focused on roadway lighting, which is within the purview of transportation agencies, and do not consider lighting from vehicles, which is reviewed by (Gaston and Holt, 2018). Our goal is to outline the processes by which roadway lighting may affect wildlife species and habitats and identify those mitigating approaches that have been developed with the goal of minimizing such impacts. We then review lighting regulations that have been implemented specifically to protect wildlife and report on a series of case studies of examples of lighting systems designed to minimize the impact of artificial light at night on wildlife.

Roadway Lighting and Species Responses

Roadway lighting is installed in fixed locations and, historically, would run from dusk to dawn. Typically, all lighting of an installation would have similar spectral characteristics that were determined by the lamp type (e.g., mercury vapor, low pressure sodium, HPS, metal halide). As LEDs have become the dominant lamp type in the market, a much wider range of spectral outputs are now available. The effects of light from roadway systems can be categorized by the way light is perceived by the organism affected. These include changes in radiance and irradiance that are then detected by the sensory or visual system of

the organism and result in changes in behavior or physiology. Responses are dependent on the spatial distribution of light relative to the organism, especially for orientation and movement.

Gaps

The impact of a lighting system on various species is very hard to establish. To reduce or minimize any impact of the lighting system, there are four characteristics of the light exposure that can be controlled:

- Spectrum

- Light intensity

- Duration of exposure

- Timing of exposure

The gaps in research that have been identified as limitations to providing guidelines for the reduction in lighting impact are shown below:

- No metric for the evaluation of the impact of a lighting system on a given species or plants exists. With the variety of spectral responses for each species, the metric would have to be specific to each animal.

- No approach to comparing alternative lighting system designs and to no lighting configurations in terms of lighting impact exists.

- Limitations of measured lighting characteristics to ensure minimized impact on flora and fauna need to be established.

Metric Calculation Method

A proposed metric for the impact of nighttime lighting on an area is a comparison with naturally occurring light sources and conditions, of which the moon is the most dominant. For measurements of irradiance, the irradiance measured during different phases of the moon provides a basis for comparison with natural conditions.

Comparison with natural values of both radiance and irradiance could be used to map distribution of potential impacts from new or replaced lighting systems. Zero impact is never a possibility because all roadway lighting meets standards that exceed moonlight by at least an order of magnitude, but such benchmarking to natural conditions could be used to evaluate the spatial extent of impacts of different levels (e.g., irradiance exceeding full moon, half moon, quarter moon) and the duration of those impacts.

As highlighted, the impact of a lighting system on flora and fauna is based on two aspects of the lighting system: the spectrum of the light source and the intensity of the light source (the timing and duration can be developed from the impact of spectrum and intensity by integrating the impact of the intensity over the duration and comparing the timing to the time of the moon). These aspects can be considered as a dosage; thus, a lighting system with a higher intensity but a less reactive spectrum may be better than a dim lighting system with a more invasive spectrum.

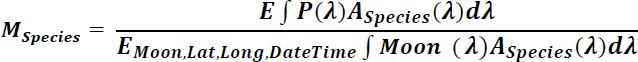

Based on the work shown in (Longcore et al., 2018), the proposed metric is the ratio of the impact of a lighting system on a given species to the impact from the moon on the same species. The proposed moon metric M is calculated as shown in Figure 2.

One of the important aspects of the moon metric is that it is linear with the design level of the lighting system. As the lighting level from the design is the numerator of the metric, an impact factor can be developed for each combination of species and light source spectrum. This impact factor would then be calculated using 1 as the lighting level. The calculated impact factor could then be considered as a normalized tool to compare the impact of spectrum on a given species.

The derivation of the impact factor would be as shown in Figure 3:

This calculation then requires the following:

- Actinic curves for a variety of species as well as a generalized sensitivity curve.

- A standard moon calculation, where the illuminance level from the moon can be calculated for a given date, time, latitude, and longitude as well as the maximum illuminance for a given latitude and longitude.

- A calculation of the lighting effects from the design under consideration.

Actinic Curve Cataloging

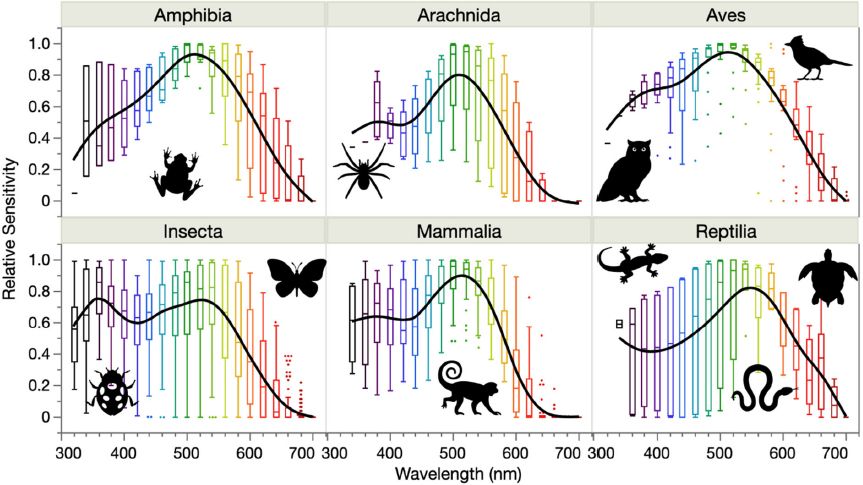

Use of spectrum to mitigate roadway lighting impacts on other species is a promising approach, as is only using the necessary amount of light for safety and directing it only on the roadway. Such “spectral tuning” has been investigated with the limited power distributions available with legacy lighting sources, and it is now being explored with the greater breadth of choices available with LEDs (Deichmann et al., 2021; Eisenbeis and Eick, 2011; Longcore et al., 2015; Longcore et al., 2018; van Grunsven et al., 2014). This approach depends on the availability of actinic curves that describe the response of an organism to different wavelengths of light. Some, such as a description of the attraction of moths to light (Cleve, 1964), have been long available, and considerable research on the sensitivity of animal visual systems was completed during the second half of the 20th century. Many of these results were not reported in digital format, so Longcore, under contract with the California Department of Transportation, compiled and

digitized these curves for as many terrestrial wildlife species as could be located using an exhaustive search strategy (Longcore, 2023). These results were combined with a database of the peak sensitivity of each photoreceptor present in terrestrial wildlife species. The generalized curves grouped by class are shown in Figure 4.

The catalog of actinic curves was complemented by a structured literature review on the effects of LEDs specifically on terrestrial wildlife (Longcore, 2023). Effects in many well-documented areas were summarized, but little evidence was found that suggested that there was anything specifically about light from LEDs that made it different from light from other sources, with the possible exception of flicker (Barroso et al., 2017; Inger et al., 2014). We therefore suggest that research on effects focus on the intensity, spectrum, duration, and distribution of the light itself, with awareness of emerging research on flicker from LEDs.

Development of the Standard Moon

The development of the moon metric must include the specification of a standard moon. Again, this would include the amount of light from the moon at different phases and the adoption of a standard moon spectrum. These two criteria are critical to defining the metric and for the calculation of the metric in a design situation.

The maximum illuminance from the moon has been found to be approximately 0.4 lux (Brown, 1952; Krisciunas and Schaefer, 1991), but under most circumstances it does not exceed 0.1 lux (Kyba et al., 2017), as shown in Figure 5. It is noteworthy in this figure that the moon’s brightness depends both on the angle of altitude and the phase of the moon. There is also an impact of the weather and the cloud layers which reduce the light reaching the Earth however this is not included in the design metric as these are transient conditions.

Calculation of the Moon Metric

The final moon metric for a species of interest is the ratio of the impact of a light source at a given design level as compared to the impact of the moon on the same species. This is calculated first by weighting the spectrum of the light source of interest by the actinic curve of the species of interest, which is then scaled by the design value. The next calculation is the impact of the moon based on the irradiance from the moon scaled to the latitude, longitude, and time of interest, which is weighted by the actinic curve for any species of interest. This follows the equations shown in Figure 2.

As the latitude, longitude, and specific time may not be an important consideration for use in a design metric, the standard illuminance of the full moon at parallax for a given latitude can be used for the moon impact. This would be considered the maximum illuminance of the moon on the Earth’s surface.

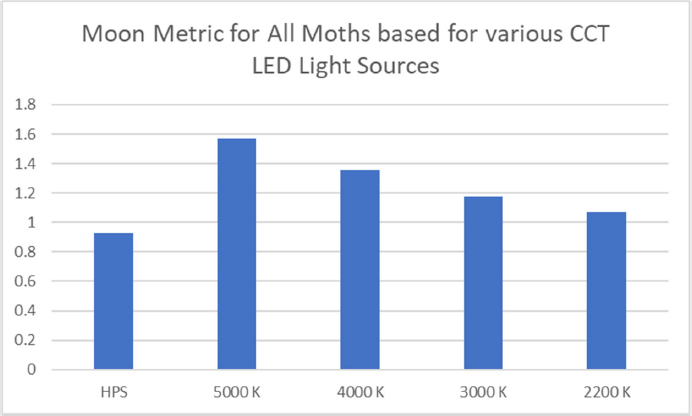

The next consideration for the moon metric was the impact of light source spectrum on the calculation. Here, five different spectral power distributions (shown in Figure 6) were used in the calculation to investigate the changes in the moon metric. The spectra with more blue content (5,000 K) have a higher impact than those with a more red or amber content.

Further calculations were performed using the same inputs as the sample calculation but with the latitude of the lighting location varying from 0 to 90 degrees. Like the time-of-day results, there is a significant variability in the data. The amount of light from the moon diminishes with increased latitude, primarily due to the low angles of elevation in the moon’s traverse. This means that the moon metric significantly increases with increased latitude.

Discussion

The developed moon model and impact factor can be used with any spectrum of light source and any actinic curve. The results from the sample calculation indicate the impact of the lighting design on a species is generally much higher than the impact of the moon, though this does vary by species and by the emission spectrum of the light source used for the lighting design. There is also considerable variation in the calculation results when variable spectral power distributions, locations, times, and dates are used. This makes the metric very difficult to use as a threshold metric. We instead recommend that the metric be used as a comparison tool when considering a specific location and alternative lighting designs.

These results and the discussion of the application highlight that the moon metric can be used as a comparison tool. However, some scoping of the magnitude of a change should be investigated to define how much of an impact is acceptable for a lighting installation.

The moon illuminance levels experienced at any location on Earth are very low compared to current lighting conditions. As a result, it is highly unlikely that any lighting design will be able to meet a 1 moon criteria. Research into an appropriate moon metric level for a lighting system is required to be able to establish lighting criteria and warrant levels. It is noteworthy that the maximum moon metric is based on the maximum moon illuminance, which means that the overall impact of the lighting system would be higher than estimated by the maximum moon metric, as the actual moon illuminance is lower than the maximum for most of the calendar and on some days it is not evident at all. As such, the use of the calculation for specific times of the year could also be considered.

The calculation results showed significant changes in the moon metric based on the light source type, the latitude, and the time of day. These criteria need to be considered as part of establishing a warranting approach to the moon metric.

Conclusions

The moon metric has been developed as a method to compare the impact of a lighting system on a given species. The input variables include the spectral power distribution of the light sources in use, the actinic response spectrum for a species of interest, the latitude and longitude of the installation location, and, optionally, the date and time of consideration.

The following are observations and conclusions from this modeling effort and sample calculations:

- The lighting levels from installed lighting systems are typically much higher than the illuminance from the moon, which means that the moon metric is much higher than 1 for most installations. This requires investigation of a design criteria to establish a lighting design recommendation based on the moon metric.

- The moon metric increases significantly with increased latitude, which is a result of diminishing illuminance from the moon with increased latitude.

- The moon metric generally follows the CCT in terms of magnitude. A higher CCT and therefore a bluer light source has a higher moon metric result. However, there is significant noise, the result of which indicates that the spectrum must be used for the metric and not simply the CCT.

- Using the time and date in the calculation will not allow for generalizable results, as the illuminance from the moon varies significantly throughout the night. However, using the maximum illuminance moon metric will underestimate the impact, as the typical moon illuminance is less than the maximum and therefore an increased moon metric is found.

- The metric is an effective comparison tool, but additional research is needed to clarify an acceptable magnitude of impact.

Recommendations

It is recommended that further application of the moon metric be investigated via the metric to consider the application limitations:

- Identify the magnitude of a change in the metric which would have an impact on a species.

- Identify a potential design metric threshold to establish a design recommendation.