Gaps and Emerging Technologies in the Application of Solid-State Roadway Lighting (2024)

Chapter: Appendix A: Gaps and Emerging Technologies in the Application of Solid-State Roadway Lighting

CHAPTER 1

Lighting Automation and the ITS Framework

NCHRP Project 05-22 produced NCHRP Research Report 940: Solid-State Roadway Lighting Design, Volume 1: Guidance, and a proposed specification for state department of transportation (DOT) adoption of solid-state lighting (SSL) luminaires; these products are intended to supplement the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) Roadway Lighting Design Guide. Research is needed to address several gaps remaining from Project 05-22 in the application of SSL in roadway lighting and to consider the impact of emerging technologies, including advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) and connected and automated vehicles (CAV). While ADAS systems provide driver assistance, CAVs introduce communication capabilities, including vehicle-to-vehicle and vehicle-to-infrastructure communications.

This report considers these issues, with the first section detailing an on-road evaluation of ADAS under varying LED lighting and environmental conditions, which establishes the impact of lighting condition on these systems. The second section of the report deals with the current state of connected vehicle (CV) technology and its implications for LED roadway lighting.

Literature Review

Approximately 94% of the motor vehicles crashes in the United States can be attributed to errors caused by human drivers (Singh, 2018). These errors by human drivers, including distraction, fatigue, failure to detect etc., could potentially be alleviated by adoption of ADAS. ADAS that include adaptive cruise control (ACC), automatic emergency braking (AEB), automated lane keeping, etc. are being increasingly found in all commercial vehicles, and give us a brief glimpse into the world of autonomous vehicles (AV).

As the number of vehicles on our roads with ADAS increases, and with increases in the testing and deployments of AVs on roads, the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA) has adopted SAE International’s taxonomy and definitions of autonomous driving systems (SAE International, 2018). According to this taxonomy, there are six levels of automation (see Figure 1): Level 0 (no automation and driver is in full control) to Level 5 (full automation and driver is just a passenger). The intermediate levels have a mix of driver control and automation control, and as the automation level is increased, the driver’s control over the motor vehicle decreases and automation takes over the driver’s responsibilities. Most of the commercial vehicles in the current market are Level 1 or Level 2 automation. Commercially available systems such as Tesla’s Autopilot and General Motors’ Super Cruise are Level 2 systems (Bigelow, 2019).

Recent research (Kyriakidis et al., 2019; Kyriakidis et al., 2015) into the public’s understanding of AV technologies has shown that they have a poor understanding of the capabilities of such systems. To safely increase the adoption of AVs, it is extremely important to understand how these vehicles respond during different weather, traffic, and lighting conditions.

Based on existing research (Kocić et al., 2018; Van Brummelen et al., 2018), there are five main parts involved in the navigation of an AV (see Figure 2). These are:

- Perception

- Localization and Mapping

- Path Planning

- Decision-Making

- Vehicle Control

In perception, sensors mounted on the vehicle continuously monitor the AV’s surrounding environment and provide information and cues to the vehicle’s computer. In localization and mapping, the vehicle’s location with respect to the roadway, surrounding vehicles, and other relevant geographical information, is processed. Path planning calculates the safe and efficient pathways for the AV to traverse based on the inputs from previous two components. The decision-making component will select the best pathways based on the information available. Finally, vehicle control will then determine the right command (increase speed, slow-down, stop, etc.) for the vehicle to follow the best pathway selected in the decision-making component.

Perception is one of the most critical components that enables an AV to sense the environment and gather information on the drivable areas, presence of obstacles, and even predict the future paths of the AV with respect to the other vehicles. Most common sensors that are used in AVs for perception are light detection and ranging sensors (lidar), radio detection and ranging sensors (radar), vision-based sensors (cameras), GPS, sonar, etc. Because the perception sensors gather information from the AV’s surrounding environment, they are always affected by the prevailing ambient weather and lighting conditions. For an AV to function seamlessly in all weather and lighting conditions or even to transfer control to the human driver, it is critical to understand how the different ambient weather and lighting conditions affect sensor performance. The following section details each of the major sensors used in AVs and the effect of weather and lighting on their performance.

Sensors Used for Perception in Autonomous Vehicles

Vision-Based Sensors

A camera is an example of a vision-based sensor. Cameras mounted on various locations on a vehicle (or on infrastructure) can provide an AV or ADAS with a visual representation of the area around it. Camera-based sensors are being used on almost all newer commercial vehicles, predominantly for object detection (Van Brummelen et al., 2018), lane departure, and lane keeping algorithms (Pendleton et al., 2017).

Cameras work by absorbing the light reflection by various objects. Cameras can also be divided into two main categories for vision sensors: a charge-coupled device (CCD) or a complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) (Sarkar, 2012). They both use millions of pixels as the photo-detection technique. CCDs respond to various shades of light. CMOSs use photodiodes to convert pixels into voltage. CCDs produce less noise and have higher quality, but they are more expensive. CMOSs are preferred for car vision sensors, because they have a higher dynamic range, can be used in harsh weather conditions, and have a wider field of view.

In some situations, two or more cameras are used together to provide better depth of field (Rasshofer and Gresser, 2005) and additional color and texture information from the environment (Sivaraman and Trivedi, 2013). These systems are called stereovision systems. These systems are better for object classification and have a longer range than single camera systems that increase the detection performance (Van Brummelen et al., 2018).

Like human vision, camera-based sensors have more difficulty in low visibility conditions, such as darkness, fog, rain, or snow, than in well-lit situations (Rasshofer and Gresser, 2005; Sivaraman and Trivedi, 2013). However, camera vision is still possible under these conditions, and it is unclear whether this limitation is a key concern of technology companies, or whether it is not seen as a significant challenge when considering both anticipated technology improvements as well as inputs from other sensors. Camera-based sensors (both mono and stereovision) are also computationally expensive (Huber and Kanade, 2011; Maddern and Newman, 2016; Sivaraman and Trivedi, 2013). Research into the interaction between vehicle headlamps and street lighting has shown that when the luminance of the object is equal to luminance of the

background area, the object could not be detected by camera-based sensors (Bhagavathula et al., 2020; Gibbons et al., 2015).

Radar

Radar, or radio detection and ranging, is used in AVs and ADAS for mid-range (100–150 m) and long-range (more than 200 meters) object detection (Al Henawy and Schneider, 2011; Leonard et al., 2008). It uses electromagnetic radiation in several frequency bands (24 GHz, 77 GHz etc.) (Ilas, 2013). Radar directly provides object speed (Leonard et al., 2008) and is commonly used for features like adaptive cruise control (Varghese and Boone, 2015). One of the major benefits of radar is that its performance is not affected by weather or lighting conditions and provides highly accurate data (Rasshofer and Gresser, 2005).

Radar systems also suffer from some drawbacks. Radar sensors cannot be used for object classification (Leonard et al., 2008) and can give false alarms, especially when there are multiple reflections from the same source (Van Brummelen et al., 2018). Due to their poor object classification, radar sensors have difficulty in pedestrian and static object detection. Another drawback that affects radar sensors is that their field of view is limited, especially at longer ranges, and they perform poorly at distances less than two meters (Rasshofer and Gresser, 2005).

Lidar

Lidar is a detection system that uses infrared light beams to build a 3-dimensional understanding of the area around a vehicle. Lidar sensors typically use light in the wavelength range of 900 nm (Kocić et al., 2018). In a typical lidar sensor, a laser beam swivels across the field of view. The laser’s pulses are emitted and reflected back. These reflected pulses help in the construction of a 3D environment around the AV. Lidar sensors have a higher spatial resolution than radar sensors (Kocić et al., 2018).

One of the advantages of lidar sensors is that they are not affected by low lighting levels in the environment. Lidar sensors can also provide direct distance measurements (Van Brummelen et al., 2018) and have large fields of view with high resolution and range of up to 200 meters (Rasshofer and Gresser, 2005). Lidar sensors also have the ability to map a static environment and also detect moving objects found on the roadway, such as pedestrians, other vehicles, bicyclists, and animals (Kocić et al., 2018).

One of the major disadvantages of lidar is its poor performance in rain, fog, and snow (Rasshofer and Gresser, 2005). One study (Tang et al., 2020) that measured the pedestrian detection performance of a lidar sensor in rain and clear weather showed that the detection failure percentage increased by 33% in rainy weather. The same study also reported that the orientation of the pedestrian also affected the lidar sensor’s pedestrian detection capability. The classification capability of lidar sensors is also lower than that of cameras (Bacha et al., 2008).

Other Sensors

Other devices and sensors that AVs use are not sensitive to light or weather conditions. These sensors and devices can be used to provide redundancy for times when other sensors are limited in their abilities. Currently, a significant portion of traffic collisions occur at night, and it is already less safe to drive or walk in low-light conditions (Schneider, 2020). Therefore, these types of sensors could also be used in ADAS applications to support human drivers, as well as for the deployment of new AV systems.

Ultrasonic Sensors

Ultrasonic sensors use sound rather than light, so they work in applications where other sensors that depend on light may not. This is especially useful for high-glare environments, as well as for the detection

of clear objects and highly reflective or metallic surfaces. Ultrasonic sensors could provide an alternative, or redundant, sensor type to help in certain lighting conditions.

Ultrasonic sensors have their own limitations. For example, they are sensitive to temperature fluctuations, wind, and some types of noise interference (Varghese and Boone, 2015), but they could be used as a complementary technology to visual cameras and other AV sensors, especially to resolve limitations related to lighting conditions (Banner, 2020). Ultrasonic sensors also have poor detection capability beyond a 2-meter range have poor angular resolution (Rasshofer and Gresser, 2005).

Infrared/Thermal Sensors

Thermal/infrared cameras can help AVs travel at night by sensing signals from objects radiating heat, such as pedestrians and wildlife. Infrared/thermal sensors do not require any light to accurately detect, segment, and classify objects and pedestrians and thus could improve an AV’s nighttime object detection capabilities (Varghese and Boone, 2015). Standard car headlamps can assist in seeing up to 100–150 meters at night. However, infrared systems can improve the range to more than 450 meters (Sarkar, 2012). Shaharabani (2018) argues that AVs could use high-resolution thermal cameras to passively collect infrared signals and convert them to high-resolution video, supplementing detections from other sensors in low-light conditions, particularly darkness and fog.

GPSs and Other Localization

GPSs and other localization systems are generally used by AVs and ADAS for navigation purposes, and not for object detection or other tasks that cameras, lidar, radar and other sensors cover. GPSs are not impacted by light or weather, but they could be used to detect when a vehicle is in an area where past behavior has indicated that using different suites of sensors is necessary, and the vehicle system could respond appropriately before any limitations arise (Cast-Navigation, 2018). Such locations could be tunnel entrances and exits, areas with artificial lighting systems that hinder AVs, or areas where sunlight at certain times of day is unfavorable. Further, data provided by a GPS could also be used to validate and calibrate other vehicle sensor data and provide feedback to other vehicle systems to correct any errors, if present (Varghese and Boone, 2015).

Vehicle-to-Infrastructure Communication

CV technology allows vehicles to communicate with each other and with infrastructure to communicate vital information. CV technology does not need to be deployed alongside AV technology; however, deploying both technologies at the same time can allow each to augment the benefits of the other (FHWA, 2017).

Information provided to a CV could be especially useful for obtaining information on the traffic signal state, which is particularly susceptible to not being visible in all light conditions. CV technology could also be used to communicate information from a vehicle to a lighting system, telling it when to dim, turn on, etc., and could be used to detect pedestrians that are outside the line of sight of vehicle sensors.

Deploying CV technology alongside AV technology could be a potential solution for mitigating AVs’ limitations, and in particular the interactions between their sensors and lighting systems. Systems are still under consideration for vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I), infrastructure-to-vehicle (I2V), and vehicle-to-everything (V2X) systems, with options including direct communication with the streetlighting or through the roadside units (RSU), but much development still needs to be done.

However, recent Federal Communication Commission (FCC) decisions are forcing a pivot away from the original technology intended for V2I, dedicated short-range communications (DSRC). This development makes any near-term integration with lighting systems unlikely. On November 18, 2020, the FCC voted to repurpose the spectrum currently allocated for DSRC, effectively sunsetting the technology, and it its place, offer a smaller but exclusive spectrum to a newer technology: cellular V2X (C-V2X). Given that C-V2X is still in its infancy, it is expected that the initial focus of the technology will be to fill

the void of DSRC related to eminent crash prevention, requiring signal phase and timing data and map rather than on lighting control. As such, integration of V2I with lighting control systems is still likely years away.

Sensor Fusion

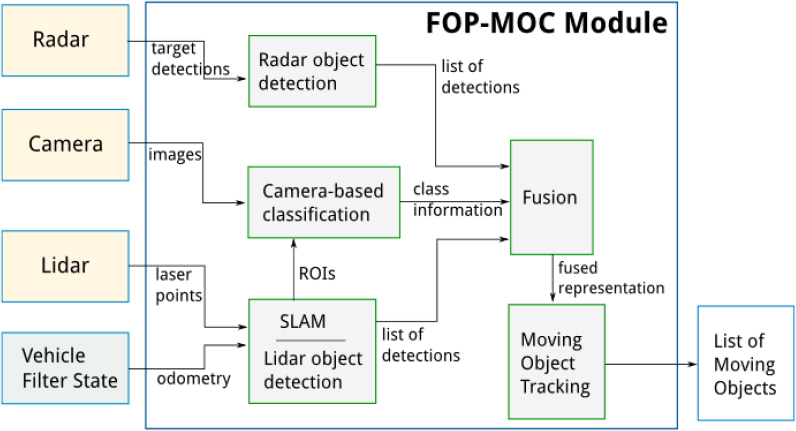

The drawbacks of individual sensor types could be overcome by fusing inputs from multiple sensor types. This is called multi-sensor fusion and research has shown that this approach increases the accuracy, reliability and robustness of perception, especially in AVs (Bresson et al., 2016; Dasarathy, 1997; Gruyer et al., 2016; Kaviani et al., 2016; Sasiadek and Wang, 2003). For example, a camera could be coupled with a lidar and/or radar system to improve nighttime or moving object detection performance (Chavez-Garcia and Aycard, 2015). A block diagram of a multi-sensor fusion system that uses a camera with radar and lidar is shown in Figure 3.

Challenges and Gaps in Research

Based on the review of research related to sensors used in AVs and ADAS, the following challenges and gaps in research have been identified:

- Sensor performance in poor weather conditions like rain, fog, and snow inhibit the use of AVs and ADAS. While some sensors, such as radar, are not majorly affected by poor weather, these sensors alone cannot provide enough information for AVs or ADAS to operate safely.

- Sensor performance in low or no light conditions is another major issue that could inhibit the use of AVs or ADAS. Lidar systems could be used in no light conditions, but these sensors are expensive and the noise from the lidar data at night could also hinder AV performance (Jo et al., 2017).

- Using multi-sensor fusion or V2I/I2V communication could cover some of these sensor performance issues. At night or in low-light conditions, AVs could communicate with streetlights, triggering them to brighten so that camera-based sensors could perform object detection tasks more accurately. However, more research is required on light levels required to maintain sensor performance at night or in low-light conditions.

CHAPTER 2

Experimental Approach

In response to the gaps developed above, an initial research effort was undertaken to consider vehicles equipped with ADAS features, specifically, automatic emergency braking (AEB). In this case the investigation included the testing and evaluation of ADAS performance in a lighted environment. The results of this investigation are used to provide recommendations for any modifications that need to be made to lighting recommendations for these systems.

In this first portion of the research, the effects of LED roadway lighting on ADAS were evaluated. The team conducted an experiment in which the performance of a vehicle equipped with an ADAS was measured under varying lighting and pavement conditions. The current study specifically focused on the performance of the AEB system. The goal of the current study was to evaluate the performance of the AEB system under varying lighting and pavement conditions to verify if the existing lighting standards for LEDs are adequate for the AEB system to perform optimally.

Research Questions

This research will allow state DOTs and municipalities to future-proof lighting systems under consideration for installation. The expected service life of newly installed LED luminaires will likely fall within the timeframe of emerging automated and autonomous vehicle technologies. From a lighting perspective, the key elements for consideration include:

- What possible impact might the roadway lighting system’s spectral content have on ADAS?

- What is the impact of lighting levels on ADAS?

- What should be installed now to accommodate any future changes?

- What are the effects of varying pavement conditions (i.e., wet and dry) and the interactions between roadway lighting systems and ADAS technologies during these pavement conditions?

- If issues are discovered, a review of what changes in the lighting system could be considered to help mitigate the impacts of pavement conditions and other environmental factors.

Methods

This experiment was conducted on the Virginia Smart Roads, a suite of research facilities that include a 2.5-mile-long, controlled-access research facility built to U.S. highway specifications. The experimental results are highly generalizable and readily applicable to real roads. The Smart Roads are equipped with a weather making and variable lighting system that were used to investigate CAV and ADAS needs.

An adult sized mannequin was used as a potential hazard. The experiment included light levels and color temperatures consistent with existing practices for roadway lighting. Test conditions also included dry and wet pavement. The ADAS was evaluated at 20 and 30 mph. The proposed experimental design is shown in Table 1.

The research team used a 2019 Subaru Outback with Eyesight. The Eyesight system relies on stereovision systems. Stereovision systems use two or more cameras together to provide better depth of

field (Rasshofer and Gresser, 2005) and additional color and texture information from the environment (Sivaraman and Trivedi, 2013). Stereovision systems are better for object classification and have a longer range than single camera systems that increase the detection performance (Van Brummelen et al., 2018). Other commercially available systems include Toyota Safety Sense, which uses a monocular camera and radar fusion system (Ono et al., 2016) and Nissan ProPILOT, which also uses monocular cameras (Vdovic et al., 2019). Subaru was chosen because the research team was unable to access CAN data from other manufacturers.

Table 1. Independent variables and their experimental levels.

| Independent Variable | Levels |

|---|---|

| Light Type and Level | 2200 K LED High – 1.0 cd/m2 |

| 2200 K LED Medium – 0.6 cd/m2 | |

| 2200 K LED Low – 0.3 cd/m2 | |

| 3000 K LED High – 1.0 cd/m2 | |

| 3000 K LED Medium – 0.6 cd/m2 | |

| 3000 K LED Low – 0.3 cd/m2 | |

| 4000 K LED High – 1.0 cd/m2 | |

| 4000 K LED Medium – 0.6 cd/m2 | |

| 4000 K LED Low – 0.3 cd/m2 | |

| No Fixed Roadway Lighting - <0.05 cd/m2 | |

| Pavement Condition | Dry Pavement |

| Wet Pavement | |

| Pavement Surface Type | Concrete |

| Asphalt | |

| Vertical Illuminance on Mannequin | Bright – 20 lux |

| Dark – 2 lux | |

| Mannequin Orientation | Parallel – Facing the Vehicle |

| Perpendicular – Facing the Road | |

| Speed | 20 mph |

| 30 mph |

Independent Measures

Light Type and Light Level

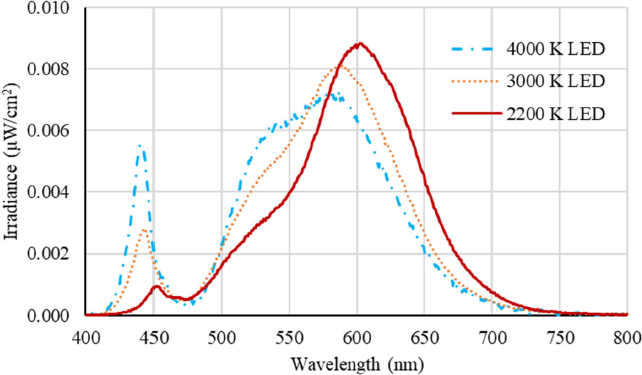

Three roadway lighting types were evaluated in this experiment. They are 4000 K LED, 3000 K LED, and 2200 K LED light sources and are the range of correlated color temperatures (CCTs) available for roadway lighting. The spectral power distributions are shown in Figure 4.

Pavement Conditions

The performance of the ADAS was evaluated in two different pavement conditions: dry and wet.

Pavement Surface Type

The Virginia Smart Roads have both asphalt and concrete pavement surfaces in the lighted section. Both asphalt and concrete surfaces have different pavement reflectance properties, which could affect sensors that rely on computer vision.

Vertical Illuminance on Mannequin

Two locations were selected between a cycle of luminaires on the Smart Roads, which corresponded to two different vertical illuminances on the mannequin. These two vertical illuminances comprised a higher level of 20 lux, which is the highest recommended light level for pedestrian crosswalks and a 2 lux, which is the recommended for sidewalks. Levels of illuminance were established in the field during the development of the experimental protocol.

Mannequin Orientation

The orientation of the pedestrian could affect its detection. Two different orientations were chosen. First was a parallel orientation where the pedestrian was facing the test vehicle (see Figure 5a). The second was a perpendicular orientation where the mannequin was facing the road and was perpendicular to the vehicle (see Figure 5b). For both the orientations, the mannequin was located at 3 ft from the pavement marker in the vehicle’s travel lane.

Speed

Two different speeds were selected for evaluating the ADAS’s performance: 20 mph and 30 mph. The former (20 mph) is the lowest speed at which the ADAS could be activated. Beyond 30 mph, the vehicle did not consistently stop before the 10-ft cone in pilot testing; thus 30 mph was used as the highest speed limit.

Dependent Measures

For this study, the research team evaluated the performance of the test vehicle’s AEB system. Three different dependent measures were selected to be evaluated in the current study.

AEB Activation

Under each combination of the independent variables, the vehicle’s AEB subsystem was tested to see if AEB could be activated or not. The AEB was recorded to be activated if the vehicle stopped safely before the mannequin. The AEB was recorded to be inactivated if the in-vehicle experimenter decided that the vehicle was not going to stop before hitting the mannequin and had to swerve to avoid hitting it. A cone was placed 10 m (32.8 ft) from the mannequin, and if the vehicle showed no signs of slowing down at the 10 m (32.8 ft) cone then the in-vehicle experimenter took control of the vehicle and performed an evasive maneuver, and the trial was recorded as AEB not activated.

Deceleration

The rate at which the vehicle slowed down under each of the experimental conditions was also recorded and used as a dependent measure. A slower deceleration rate is preferred for a smoother and safer ride.

Distance at Braking Initialization

An adult sized mannequin (see Figure 5) was used as decoy hazard in each of the experimental conditions. The distance at which the vehicle started to break as a response to the presented mannequin was recorded.

Procedure

For each trial, two distances were marked. First was the start location: 300 m (984.2 ft) from the location of the mannequin (see Figure 6). This allowed for adequate acceleration for the establishment of measuring system performance. The second location was marked at a distance of 10 m (32.8 ft) from the mannequin. This was the distance at which, if the AEB was not engaged and the vehicle was not slowing down, the in-vehicle experimenter would take control of the vehicle and swerve to avoid the hitting the mannequin (see Figure 6). It should be noted that the position of the pedestrian relative to the luminaires varied depending on the level of vertical illuminance that was needed for the trial. For each trial, the in-vehicle experimenter would gently accelerate to the test speed and then engage the cruise control and wait for the AEB system to stop the vehicle as it approached the mannequin. Three trials were performed for each of the combination of the independent variables with test vehicle to evaluate the performance of the AEB system. Multiple trials ensured the consistency of the AEB system’s performance. The test vehicle was instrumented with a data acquisition system (DAS) from the vehicle’s CAN system, including vehicle speed, differential global positioning system (DGPS) coordinates, and inputs from the experimenters.

Data Analysis

Three analysis approaches were used to assess the effects of the light type and level and other independent variables on the performance of the AEB system on the test vehicle. First, a repeated measures logistic regression was used to assess the effect of the independent variables on the odds of the activation of the AEB system. Subsequently, two linear mixed models (LMMs) were used to assess the effect of light type and level on the deceleration and the distance to braking initialization.

Repeated Measures Logistic Regression

A repeated measures logistic regression was used to assess the odds of the AEB system’s activation because probability of the detection follows a non-normal distribution. The model follows a similar structure to that of a linear regression model. However, in a logistic regression model, there are no assumptions about the distributions of the predictor variable, which means the predictors do not have to be

normally distributed or linearly related. The result is a prediction based on a set of variables inserted into the model.

The model coefficient pi represents the probability of AEB activation for observation i. It is assumed that this detection probability will be influenced by factors such as light type and level, pavement conditions, pavement surface type, speed, etc. This connection between the potential factors and the detection pi can be mathematically modeled through a logit link function with the following form:

Where Xki is the variable based on independent variable k and βk is the corresponding regression coefficient. With proper parameterization, the exponential of the regression coefficient βk corresponds to the odds ratio (OR) for the kth factor. For example, for a binary variable Xi, the odds ratio can be calculated as:

ORk = exp(βk)

The ORk indicates the relative risk of violation for the two levels of an independent variable. For a continuous variable, the odds ratio indicates the increase or decrease of the relative risk for every change of one unit in the independent variable. The neutral value of the odds ratio is 1. As the odds ratio increases beyond 1, the likelihood of detecting an object increases. As the value decreases below 1, the likelihood of detection decreases, or the system may miss the object based on the ratio calculated.

The main advantage of the odds ratio estimated from the logistic regression is that the odds ratio of a specific factor can be considered as an averaged value over all the levels of other factors included in the same model. Therefore, the confounding effect can be effectively addressed by simply including multiple factors that might confound with each other simultaneously in the model.

Given this model, a variety of predictors can be entered, and the resulting odds of AEB activation based on a number of independent variables can be achieved.

Linear Mixed Models

Overall, two separate LMMs were used to assess the effects of the independent variables on deceleration, and distance to braking initialization. Level of significance was established at p < 0.05, and post hoc comparisons were performed using Tukey’s honest significant difference.

CHAPTER 3

Results

Repeated Measures Logistic Regression – Odds of AEB Activation

The logistic regression model converged, and the results are presented in Table 2 for easier interpretation. Almost all the independent variables were significant.

Table 2. The odds ratio estimation for AEB activation.

| Parameter | Level | Comparison | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light Type and Level | 2200 K LED Low | No Fixed Roadway Lighting | 1.20 | 0.76 | 1.90 | 0.4403 |

| 2200 K LED Med | 2.34 | 1.48 | 3.68 | 0.0003 | ||

| 2200 K LED High | 0.73 | 0.65 | 0.82 | <.0001 | ||

| 3000 K LED Low | 0.62 | 0.47 | 0.82 | 0.0008 | ||

| 3000 K LED Med | 1.93 | 1.53 | 2.42 | <.0001 | ||

| 3000 K LED High | 1.60 | 0.56 | 4.55 | 0.3798 | ||

| 4000 K LED Low | 1.21 | 1.09 | 1.35 | 0.0005 | ||

| 4000 K LED Med | 1.42 | 1.30 | 1.56 | <.0001 | ||

| 4000 K LED High | 1.04 | 0.72 | 1.50 | 0.8415 | ||

| Mannequin Orientation | Perpendicular | Parallel | 0.46 | 0.44 | 0.49 | <.0001 |

| Vertical Illuminance on Mannequin | 2 lux | 20 lux | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.95 | 0.0024 |

| Pavement Condition | Wet | Clear | 0.72 | 0.63 | 0.83 | <.0001 |

| Pavement Surface Type | Asphalt | Concrete | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.39 | <.0001 |

| Speed | 30 mph | 20 mph | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.16 | <.0001 |

For most of the light type and level conditions, the odds of AEB activation were higher in the lighted conditions than in the no fixed roadway lighting condition. For two of the light type and level combinations (2200 K LED High and 3000 K LED Med), the odds of AEB activation were lower in the lighted condition than in the no fixed roadway lighting condition. The odds of AEB activation were lower (by 64%) when the mannequin was oriented perpendicular compared to parallel. The odds of AEB activation were lower at the lower vertical illuminance compared to the higher vertical illuminance (by 14%). In wet pavement conditions, the odds of AEB activation were lower by 28% compared to clear conditions. The odds of AEB activation were 72% lower in asphalt pavement compared to concrete pavement. Finally, the odds of AEB activation at 30 mph was 90% lower than the odds of AEB activation at 20 mph.

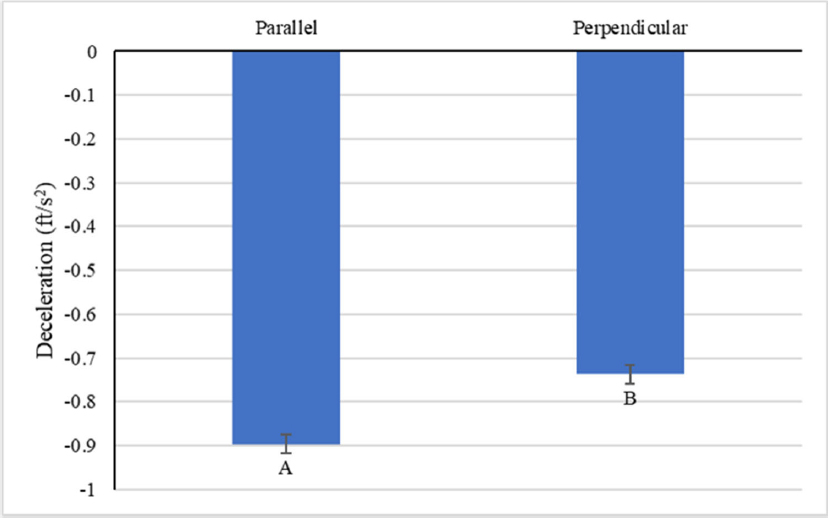

LMM – Deceleration

Statistically significant results of the LMM on the effects of the independent variables are shown in Table 3. The main effects of mannequin orientation, pavement condition, pavement surface type and speed were significant. Post hoc pairwise comparisons of the deceleration under two different mannequin orientations showed that deceleration was higher when the mannequin was parallel than when the mannequin was perpendicular (see Figure 7).

Table 3. Statistical results from linear mixed model analysis of deceleration.

| Source | Num DF | Den DF | F Value | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mannequin Orientation | 1 | 45.6 | 29.03 | <.0001 |

| Pavement Condition | 1 | 535.5 | 6.45 | 0.0114 |

| Pavement Surface Type | 1 | 529.8 | 325.29 | <.0001 |

| Speed | 1 | 45.6 | 135.89 | <.0001 |

Post hoc pairwise comparisons of deceleration under pavement types showed that deceleration was significantly higher on asphalt than on concrete pavement (see Figure 8).

Deceleration was statistically higher in wet pavement conditions than in the dry pavement condition (see Figure 9).

Finally, Decelerations were significantly higher in the 30-mph condition than in the 20-mph condition (see Figure 10).

LMM – Distance to Braking Initialization

Statistically significant results of the LMM on the effects of the independent variables on distance to braking are shown in Table 4. The main effects of light type and level, vertical illuminance on mannequin, pavement type and speed are significant. Post hoc pairwise comparisons of the distance to braking showed that in most of the cases increase in light level resulted in an increase in the distance at which braking was initialized except for the 2200 K LED High condition (see Figure 11).

Table 4. Statistical results from linear mixed model analysis of distance to braking initialization.

| Source | Num DF | Den DF | F Value | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light Type and Level | 9 | 94.6 | 4.68 | <.0001 |

| Vertical Illuminance on Mannequin | 1 | 50.7 | 80.27 | <.0001 |

| Pavement Type | 1 | 535.5 | 322.07 | <.0001 |

| Speed | 1 | 47.2 | 625.72 | <.0001 |

Increase in vertical illuminance on the mannequin resulted in an increase in the distance at which braking was initialized (see Figure 12).

Post hoc pairwise comparisons of the effect of pavement type on distance to braking initialization showed that, for concrete pavement, the distance at which braking initialized was significantly higher than for asphalt pavement (see Figure 13).

Post hoc pairwise comparisons of the effect of speed on distance to braking initialization revealed that at 20 mph, the distance at which braking initialized was statistically longer than the distance to braking initialization at 30 mph (see Figure 14).

CHAPTER 4

Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the performance of an AEB system in a variety of lighting and pavement conditions. Three analysis approaches were used to investigate the different factors that affect AEB activation, including logistic regression, and two LMMs for deceleration and distance to braking initialization. The findings from the three analysis approaches provided important insights into the factors that affect the performance of the AEB system.

The results from the logistic regression analysis indicate that light type and light level, mannequin orientation, vertical illuminance, pavement type, and speed all have significant effects on the odds of AEB activation. The odds of AEB activation were higher in the lighted conditions than in the no fixed roadway lighting condition, except for a couple of light types and levels. The odds of AEB activation were lower when the mannequin was oriented perpendicular compared to parallel, indicating that the system may have difficulty detecting the mannequin when it is not in a standard orientation. The odds of AEB activation were also lower at the lower vertical illuminance, suggesting that the system is more accurate when the mannequin is well illuminated. Finally, the odds of AEB activation were higher for concrete pavement compared to asphalt pavement.

The results from the LMMs’ analysis on deceleration further support the findings from the logistic regression analysis. The main effects of mannequin orientation, pavement condition, pavement surface type, and speed were significant factors affecting deceleration. The deceleration was higher when the mannequin was parallel compared to perpendicular, on wet pavement compared to dry pavement, on asphalt pavement compared to concrete pavement, and at 30 mph compared to 20 mph. This is likely due to the difference in detection distance, as presented in Figures 9, 10, and 11. These findings suggest that the system performs better at detecting the mannequin under certain environmental conditions, such as well-lit conditions and dry pavement, and on certain types of pavements like concrete, which reflect more light and in turn result in higher ambient lighting conditions.

Finally, the results from the LMMs’ analysis on the distance to braking initialization provide important insights into the effect of lighting, vertical illuminance, pavement type, and speed on AEB system performance. The findings that increase in light level and vertical illuminance result in an increase in the distance at which braking is initialized are important, as they suggest that the system requires more time to detect the obstacle under brighter conditions. Additionally, the finding that the distance to braking initialization is longer on concrete pavement than on asphalt pavement is consistent with the finding from the logistic regression analysis. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have shown that speed, weather (Černý et al., 2023; Decker et al., 2021; Haus, 2021), and lighting (Cicchino, 2022; Decker et al., 2021; Haus, 2021) can affect the performance of AEB systems.

These results have important implications for the use of AEB systems in detecting pedestrians on roadways at night. By identifying the light type and light level, and other environmental conditions that affect the accuracy of the system, these findings can inform the development and improvement of such systems to enhance pedestrian safety. For example, increasing the vertical illuminance of the pedestrian could improve the accuracy of the system, as could developing algorithms that can detect pedestrians in non-standard orientations. Interestingly, these results also indicate the correlated color temperature of the light source did not have a major effect on the performance of the AEB system. Additionally, the findings

suggest that using the system on well-lit roads (greater than 0.3 cd/m2), dry pavement, and on concrete pavement could result in more accurate AEB activations.

This study has some limitations. First, only one vehicle’s AEB system was evaluated in varying lighting and pavement conditions. This approach was taken as other vehicles’ systems could not be integrated with the DAS and key performance measures could not be collected. Second, there was no additional traffic on the Smart Roads during testing. This simplification was made to reduce the confounding effects related to the presence of traffic and changes in headlamp glare of vehicles approaching in the opposite direction. Third, the mannequin which was used as a simulated pedestrian did not move and was stationary. In reality, pedestrians are never stationary; this simplification was made to ensure consistency in the position of the mannequin during each trial. Future research should focus on addressing these limitations to add to the body of knowledge on the performance of Level 2 ADAS in varying lighting and pavement conditions.

Finally, machine vision technologies rely on visible light for AEB, and are also significantly affected by the same limitations as human eyes. For optimal performance at night, an AEB system should be able to detect pedestrians and track them on the vehicle’s approach to avoid collisions. Absence of, or inadequate, road lighting may not provide enough visual information to the machine vision system, and it might become extremely difficult for the system to track pedestrians and other hazards, thus adversely affecting system performance. For an AEB system to perform optimally at night, developers should thus consider using alternative approaches, such as measuring color contrast, information from secondary sensors (e.g., radar), or infrared, in addition to using machine vision.

CHAPTER 5

Conclusions and Recommendations

In conclusion, the findings from the three analysis approaches provide important insights into the factors that affect the performance of AEB systems. The results suggest that lighting conditions, mannequin orientation, vertical illuminance, pavement surface type, pavement condition, and speed are all significant factors that affect the performance of AEB systems. It is noteworthy that these systems show the same limitations on performance that human eyes have. Therefore, it is expected that the same lighting configuration that is used for humans would be effective for these systems. These findings have important implications for the design and implementation of AEB systems and can help improve the safety of automated and autonomous vehicles and reduce the risk of accidents on the road.

Recommendations

Based on the results of the study, the following recommendations can be made to increase the accuracy of ADAS systems such as AEB under roadway lighting conditions. Readers should recall that these recommendations are based on data from a vehicle traveling at speeds of 25 mph and 30 mph.

- Roadways should be illuminated to average luminance of greater than 0.3 cd/m2. Based on the testing conducted in this study, vertical illuminance of 20 lux is recommended for pedestrians for optimal performance of AEB systems. The current American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) Roadway Lighting Design Guide recommends horizontal illuminance of between 14 and 24 lux in areas of high pedestrian use; the guide indicates that some lighting guides recommend equal horizontal and vertical luminance (AASHTO, 2018).

- On roadway surfaces that are darker, like asphalt, a higher light level is recommended to increase the accuracy of ADAS components that rely on machine vision.

- On roadways with speeds higher than 20 mph, it is important to augment the AEB system with additional sensors to improve their accuracy and performance.

CHAPTER 6

Connected Vehicle Technology and its Implications for Solid-State Lighting

This second part of this report considers the current state of CV/infrastructure technology. As highlighted in the experimental effort in the previous section, there is significant variability in the performance of even one vehicle’s use of an AEB system under different lighting conditions. To enhance this discussion, consideration should be given to the potential impact of CV technological and roadway lighting. This portion of this report is intended to provide guidelines on the current state of CV technology.

Background

A CV is a vehicle equipped with some sort of wireless communication device that allows it to share information with other vehicles and objects on the roadway. CV technologies enable vehicles to communicate with infrastructure (vehicle-to-infrastructure, or V2I), between vehicles (vehicle-to-vehicle, or V2V), and with other objects on the roadway such as bicycles, pedestrians, or obstacles (V2X).

There are many potential mediums by which connectivity can be enabled. Satellite, cellular, Wi-Fi and other short-range communications all represent methods by which vehicles today are already connected, and the vehicles of tomorrow will become increasingly connected. DSRC, a WiFi-based short-range method that has been developed for high-speed low-latency situations to specifically enable safety applications, is one such medium. C-V2X, which is cellular-based, is another.

Applications for Connected Lighting

There are limited examples of V2X being used to support lighting needs, beyond V2X being used to control traffic lights. Emerging CAV- and ADAS-equipped vehicles receive information from various sensors and devices and use this information to inform decisions on the vehicle’s movement. While many sensors, such as GPS and odometry, are not sensitive to light conditions, others, such as visual cameras, lidar, and radar, may be impacted by light in certain conditions, such as dawn and dusk, full darkness, glare in bright sunlight, and/or rapid changes in lighting conditions when entering and exiting settings such as tunnels and underpasses. However, research on the impact of these conditions is limited.

Other devices and sensors that ADAS-equipped vehicles use are not sensitive to light or weather conditions. These sensors and devices can be used to provide redundancy for when the other sensors are limited in their abilities. Currently, a significant portion of traffic collisions occur at night, and it is already less safe to drive or walk in low-light conditions (Schneider, 2020). Therefore, these types of sensors could also be used in ADAS applications to support human drivers, as well as for the deployment of new autonomous vehicle (AV) systems. CV technology does not need to be deployed alongside AV technology; however, deploying both technologies at the same time can allow each to augment the benefits of the other (FHWA, 2017).

Information provided to a CAV could be especially useful for obtaining information on the traffic signal state, which is particularly susceptible to not being visible in all light conditions. CV technologies could be

used to communicate information from a vehicle to a lighting system, telling it when to dim or turn on, and could be used to detect pedestrians that are outside the line of sight of vehicle sensors.

Deploying CV technology alongside AV technology could be a potential solution for mitigating the limitations of AV, and in particular the interactions between their sensors and lighting systems. The drawbacks of individual sensor types could be overcome by fusing inputs from multiple sensor types. This is called multi-sensor fusion and research has shown that multi-sensor fusion increases the accuracy, reliability and robustness of perception, especially in AVs. For example, a camera could be coupled with a lidar and/or radar to improve nighttime or moving object detection performance (Chavez-Garcia and Aycard, 2015).

Using multi-sensor fusion or V2I/I2V communication could be used to cover some of these sensor performance issues. At night or in low-light conditions, AVs could communicate with streetlights to brighten so that camera-based sensors could perform object detection tasks more accurately. However, more research is required on light levels required to maintain sensor performance at night or in low-light conditions.

A research study was completed in 2016 to evaluate the performance of an on-demand roadway lighting system that uses DSRC, LED luminaires, and a processor that can sense vehicles and turn on the LED roadway lighting only when needed (Gibbons et al., 2016). This study also assessed whether cellular technology could be used instead of DSRC, but this was not considered feasible at the time due to the higher level of latency, particularly associated with having to communicate through a traffic management center. DSRC has a low latency of less than 100 ms and a range of less than 1,000 m. Cellular technology has a longer range than DSRC—4 to 6 km—but its end-to-end latency at the time was 1.5 to 3.5 s (the study stated that 4G LTE could bring the promise of latency of about 30 ms in the future).

Since this study, C-V2X has emerged. While it is in many ways similar to DSRC, the distinctions between the two are important to evaluate to ensure that any application that can be supported by one technology can also be supported by the other, rather than just assuming that this will be the case. It should be noted that C-V2X is not the same as the cellular technology assessed in the 2016 study, but rather a communications technology that utilizes two interfaces: one which enables devices to communicate with a conventional cellular network and one which enables devices to communicate with each other directly, without a network.

C-V2X’s applications for roadway lighting are likely to include transmitting information from vehicles or other roadway users, such as pedestrians and cyclists, that they are approaching a location where the existing roadway lighting conditions may be insufficient, in particular to activate an on-demand roadway lighting system. This could have a significant impact on roadway safety in terms of communicating information in real time rather than needing to assess potential problem areas after the fact, especially because roadway lighting conditions can be highly variable, based on microclimates, location specifics, seasonality, and time of day. This could lead to potential energy savings and a reduction in light pollution in addition to the safety benefits and will be particularly useful for CVs that are also automated, as AVs tend to have greater challenges interacting with variable lighting environments relative to human drivers. Potential high priority locations could include roadways with light traffic at night and relatively high crash rates, as well as higher conflict areas such as intersections, pedestrian crossings, and merge areas.

One of the primary applications of CV technology has historically been communication with traffic signals, so communication with streetlights and other roadway lighting systems are likely to follow the same protocols. Initial test results indicate that, in ideal conditions, both DSRC and C-V2X technologies can reliably deliver the required basic safety messages with the low end-to-end latencies necessary for these types of applications, meaning that either technology would also be sufficient for communicating roadway lighting information between vehicles and streetlights or other infrastructure (5G Automotive Association (5GAA)). There is also evidence of a reliability advantage of C-V2X over DSRC, including in the presence

of real-world obstructions such as buildings or foliage, which may come into play in locations where an enhanced roadway lighting system would be deployed.

Conclusion and Future Directions

State DOT and other industry leaders are working on developing a path forward to deployment for V2X technology, USDOT leadership can ensure consistency and lessen any uncertainty. These new procedures will take time to unfold, new devices will take time to mature, and government procurement will take time to react.

Recommendations

As this report indicates, the uncertainty in the future usage of the bandwidth and the CV2X environment leads to uncertainty in the recommendations for lighting systems and the future links between lighting and vehicles. The recommendations at this time are:

- Install controls-ready luminaires that can be converted to control systems when the link to vehicles through CV2X or other methodologies are desired.

- If a control system is installed, ensure that the system has link or API subroutine calls that can be utilized to connect the systems to CV2X implementations.

References

5G Automotive Association (5GAA). V2X Functional and Performance Test Report: Test Procedures and Results. https://5gaa.org/content/uploads/2019/04/5GAA_P-190033_V2X-Functional-and-Performance-Test-Report_final.pdf.

Al Henawy, M., and Schneider, M. (2011). Integrated antennas in eWLB packages for 77 GHz and 79 GHz automotive radar sensors. 2011 8th European Radar Conference,

Bacha, A., Bauman, C., Faruque, R., Fleming, M., Terwelp, C., Reinholtz, C., Hong, D., Wicks, A., Alberi, T., and Anderson, D. (2008). Odin: Team victortango’s entry in the DARPA urban challenge. Journal of Field Robotics, 25(8), 467–492.

Banner. (2020). Ultrasonic Sensors 101: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved November 11 from https://www.bannerengineering.com/us/en/company/expert-insights/ultrasonic-sensors-101.html.

Bhagavathula, R., Gibbons, R. B., and Nussbaum, M. (2020). Does the Interaction between Vehicle Headlamps and Roadway Lighting Affect Visibility? A Study of Pedestrian and Object Contrast https://doi.org/10.4271/2020-01-0569.

Bigelow, P. (2019). Why Level 3 automated technology has failed to take hold. Automotive News. Retrieved November 11 from https://www.autonews.com/shift/why-level-3-automated-technology-has-failed-take-hold.

Bresson, G., Rahal, M.-C., Gruyer, D., Revilloud, M., and Alsayed, Z. (2016). A cooperative fusion architecture for robust localization: Application to autonomous driving. 2016 IEEE 19th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC).

Cast-Navigation. (2018). Robust GPS/GNSS: Driving the Future of Autonomous Vehicles. https://castnav.com/robust-gps-gnss-driving-future-autonomous-vehicles/.

Černý, J., Vanžura, M., Konšelová, T., and Skokan, A. (2023). Influence of Speed and Other External Factors on the Functioning of Automatic Emergency Braking During Unexpected Interactions With Pedestrians. IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Magazine, 15(1), 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1109/MITS.2022.3164538.

Chavez-Garcia, R. O., and Aycard, O. (2015). Multiple sensor fusion and classification for moving object detection and tracking. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 17(2), 525–534.

Cicchino, J. B. (2022). Effects of automatic emergency braking systems on pedestrian crash risk. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 172, 106686. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2022.106686

Dasarathy, B. V. (1997). Sensor fusion potential exploitation-innovative architectures and illustrative applications. Proceedings of the IEEE, 85(1), 24–38.

Decker, J. A., Haus, S. H., Sherony, R., and Gabler, H. C. (2021). Potential Benefits of Animal-Detecting Automatic Emergency Braking Systems Based on U.S. Driving Data. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, No. 2675(10), 678–688.

FHWA. (2017). Leveraging the Promise of Connected and Autonomous Vehicles to Improve Integrated Corridor Management and Operations: A Primer. https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop17001/ch1.htm.

Gibbons, R. B., Meyer, J. E., Terry, T. N., Bhagavathula, R., Lewis, A., Flanagan, M., and Connell, C. (2015). Evaluation of the Impact of Spectral Power Distribution on Driver Performance [Tech Report]. https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/35871.

Gibbons, R. B., Palmer, M., and Jahangiri, A. (2016). Connected Vehicle Applications for Adaptive Overhead Lighting (On-demand Lighting). https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/72846.

Gruyer, D., Belaroussi, R., and Revilloud, M. (2016). Accurate lateral positioning from map data and road marking detection. Expert Systems with Applications, 43, 1–8.

Haus, S. H. (2021). Effectiveness of Automatic Emergency Braking for Protection of Pedestrians and Bicyclists in the US Virginia Tech].

Huber, D., and Kanade, T. (2011). Integrating LIDAR into stereo for fast and improved disparity computation. 2011 International Conference on 3D Imaging, Modeling, Processing, Visualization and Transmission.

Ilas, C. (2013, 23–25 May 2013). Electronic sensing technologies for autonomous ground vehicles: A review. 2013 8th International Symposium on Advanced Topics in Electrical Engineering (ATEE).

Jo, J., Tsunoda, Y., Stantic, B., and Liew, A. W.-C. (2017). A likelihood-based data fusion model for the integration of multiple sensor data: a case study with vision and lidar sensors. In Robot Intelligence Technology and Applications 4 (pp. 489–500). Springer.

Kaviani, S., O’Brien, M., Van Brummelen, J., Najjaran, H., and Michelson, D. (2016). INS/GPS localization for reliable cooperative driving. 2016 IEEE Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE).

Kocić, J., Jovičić, N., and Drndarević, V. (2018, 20–21 Nov. 2018). Sensors and Sensor Fusion in Autonomous Vehicles. 2018 26th Telecommunications Forum (TELFOR).

Kyriakidis, M., de Winter, J. C. F., Stanton, N., Bellet, T., van Arem, B., Brookhuis, K., Martens, M. H., Bengler, K., Andersson, J., Merat, N., Reed, N., Flament, M., Hagenzieker, M., and Happee, R. (2019). A human factors perspective on automated driving. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science, 20(3), 223–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/1463922X.2017.1293187.

Kyriakidis, M., Happee, R., and de Winter, J. C. F. (2015). Public opinion on automated driving: Results of an international questionnaire among 5000 respondents. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 32, 127–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2015.04.014.

Leonard, J., How, J., Teller, S., Berger, M., Campbell, S., Fiore, G., Fletcher, L., Frazzoli, E., Huang, A., and Karaman, S. (2008). A perception‐driven autonomous urban vehicle. Journal of Field Robotics, 25(10), 727–774.

Maddern, W., and Newman, P. (2016). Real-time probabilistic fusion of sparse 3D LIDAR and dense stereo. 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS).

Pendleton, S. D., Andersen, H., Du, X., Shen, X., Meghjani, M., Eng, Y. H., Rus, D., and Ang, M. H. (2017). Perception, planning, control, and coordination for autonomous vehicles. Machines, 5(1), 6.

Rasshofer, R. H., and Gresser, K. (2005). Automotive Radar and Lidar Systems for Next Generation Driver Assistance Functions. Advances in Radio Science, 3.

SAE International. (2018). Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles. In Surface Vehicle Recommended Practice (Vol. J3016, pp. 35): Society of Automobile Engineers.

Sarkar, M. (2012). Vision Sensors in Automobiles: An Indian Perspective.

Sasiadek, J., and Wang, Q. (2003). Low cost automation using INS/GPS data fusion for accurate positioning. Robotica, 21(3), 255–260.

Schneider, R. J. (2020). United States Pedestrian Fatality Trends, 1977 to 2016. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, No. 2674(9), 1069–1083. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361198120933636.

Shaharabani, Y. (2018). Novel thermal imagers fill gap in autonomous vehicle sensor suite. https://www.vision-systems.com/cameras-accessories/image-sensors/article/16739350/novel-thermal-imagers-fill-gap-in-autonomous-vehicle-sensor-suite.

Singh, S. (2018). Critical Reasons for Crashes Investigated in the National Motor Vehicle Crash Causation Survey (Report No. DOT HS 812 506). (Traffic Safety Facts Crash•Stats, Issue. N. H. T. S. Administration. https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/ViewPublication/812506.

Sivaraman, S., and Trivedi, M. M. (2013). Looking at Vehicles on the Road: A Survey of Vision-Based Vehicle Detection, Tracking, and Behavior Analysis. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 14(4), 1773–1795. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2013.2266661.

Tang, L., Shi, Y., He, Q., Sadek, A. W., and Qiao, C. (2020). Performance Test of Autonomous Vehicle Lidar Sensors Under Different Weather Conditions. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, No. 2674(1), 319–329.

Van Brummelen, J., O’Brien, M., Gruyer, D., and Najjaran, H. (2018). Autonomous vehicle perception: The technology of today and tomorrow. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 89, 384–406. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trc.2018.02.012.

Varghese, J. Z., and Boone, R. G. (2015). Overview of autonomous vehicle sensors and systems. International Conference on Operations Excellence and Service Engineering.