Gaps and Emerging Technologies in the Application of Solid-State Roadway Lighting (2024)

Chapter: Appendix B: CMFs for Solid-State Roadway Lighting Applications

CHAPTER 1

CMFs for Solid-State Roadway Lighting Applications

Lighting can affect multiple aspects of safety. For example, well designed lighting extends the range of drivers’ visual detection and provides additional time for drivers to prepare for potential upcoming hazards. Lighting may also help reduce driving workload and therefore alleviate driver fatigue. On the other hand, roadway lighting may cause glare and introduce increased fixed-object crash risks. Lighting effects on safety during adverse weather conditions are also a subject of further research. The development of high-quality crash modification factors (CMFs) for lighting therefore needs to take into careful consideration several factors, such as study design, data quality and availability, sample size, and control of potential bias. In general, different CMFs can be developed for different crash types, crash severity levels, site conditions, and environmental conditions.

The CMF Clearinghouse currently uses a number of criteria to assess the quality of a CMF, including the study design, sample size, standard error, potential bias, and data source. Although most of these criteria can be relatively objectively controlled, the evaluation process is subject to opinions (CMFClearinghouse.org). Currently, NCHRP 17-72 is developing a new CMF rating procedure that revises the 5-star rating scale to a 150-point score system where CMFs scored 100 and above may be considered high-quality CMFs worthy of inclusion in the second edition of the Highway Safety Manual (HSM). The new scoring system proposed consists of three broad quality evaluation areas, including data (55 points), statistical analysis design (75 points), and statistical significance (20 points).

For before-after studies, the new scoring system requires studies to properly address issues such as regression to the mean bias, changes in traffic volume over time, suitability of reference/comparison groups, and quality of safety performance functions. For cross-sectional studies, the new system emphasizes aspects such as the similarity of sites with and without treatment, proper consideration of correlation between variables, and addressing of spatial and temporal correlations. Although on a different score scale, the new CMF scoring system is considered mostly consistent with the current star rating system when being applied to exiting CMFs in the current CMF Clearinghouse (CMFClearinghouse.org). Note that neither scoring system takes into consideration geographic regions where data is collected and therefore transferability of the results. For this reason, the rating/score of a particular CMF may not directly indicate its applicability for a specific location. For example, a 5-star fatal crash CMF developed based on European data may poorly reflect U.S. experiences.

This portion of the project provides guidelines on how to develop high-quality CMFs for roadway and street lighting measures based on this research, relevant literature, and the research team’s experience. While the results of this project are not immediately implementable, the results highlight data and informational needs to develop high-quality CMFs for local roads and residential areas.

Literature Review

Driving is a visual task, and drivers rely on the timely detection and identification of objects while driving to ensure safety. Roadway lighting intends to improve roadway and object visibility in dark driving

environments and therefore benefits drivers’ visual performance. Roadway lighting systems can affect traffic safety in different ways (Bhagavathula et al., 2015; Bhagavathula et al.; Boyce, 2009; Gibbons et al., 2014; Gibbons et al., 2015) while improving drivers’ detection distances of pedestrians, objects, strategic roadway locations, and navigational paths during nighttime, lighting systems introduce fixed objects along roadways and potentially discomforting glares for drivers. Roadway lighting also interacts with adverse weather conditions and glare from oncoming traffic, resulting in favorable conditions in some cases and negative effects during other conditions.

Compared to traditional lighting systems, modern solid-state lighting (SSL) technologies in the form of LED systems may have different safety effects due to their unique characteristics in light quality and controls. For example, some studies (Bhagavathula et al., 2020; Jin et al.; Lutkevich et al., 2020) have shown that LED systems at 4000 K correlated with longer detection distances, particularly for pedestrians, than other light types and LED systems with a correlated color temperature (CCT) of 3000K or higher were associated with color discrimination success rates near 100%. Better designed uniformity, illuminance levels, and surround ratio with LED systems could also improve pedestrian and object detection during nighttime and therefore benefit safety.

Previous research on the safety impacts of roadway lighting mostly focused on how the presence of lighting affected nighttime crashes by comparing highways with and without lighting and the relationship between day and night crashes (Box, 1989). Results of those studies varied significantly, with some pointing to a positive safety impact of roadway lighting and others indicating insignificant safety benefits of roadway and street lighting. The results of some representative studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of previous studies on safety impacts of roadway lighting.

| With-without comparison analysis |

| Before-after comparison based on Poisson regression analysis |

| Before-after comparison based on case-control and cross-sectional analysis |

| With-without comparison based on inverse binomial regression |

| Cross-sectional negative binomial analysis |

| Cross-sectional negative binomial analysis |

| Cross-sectional study using random parameter negative binomial |

| Empirical Bayes method based before-after comparison analysis |

| With-without comparison study based on multiple methods |

| With-without comparison with random parameter models |

Roadway Lighting CMFs

The current CMF Clearinghouse database (Federal Highway Administration, 2020) included 95 CMFs for roadway/street lighting based on 14 studies (see Table 2). The database lists 55 CMFs for roadway

lighting based on domestic studies (including meta-analyses partially combining international findings), most of which were also reviewed in Table 1.

Table 2. Lighting CMFs included in the current CMF Clearinghouse (Federal Highway Administration, 2020).

| Countermeasure | CMF | Crash Type | Severity | Area Type | Year | Rating | State |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interchange Lighting | |||||||

| Install lighting at interchanges | 0.5 | All | All | All | 2005 | 3 | OH |

| 0.74 | All | KABC | All | 2005 | 2 | OH | |

| Full to partial interchange lighting | 0.984 | All | All | Suburban | 2008 | 3 | OR |

| 0.913 | All | ABC | Suburban | 2008 | 4 | OR | |

| 1.035 | All | All | Suburban | 2008 | 3 | OR | |

| 0.886 | All | ABC | Suburban | 2008 | 3 | OR | |

| Full lineal to no or partial lineal lighting | 0.905 | All | All | Suburban | 2008 | 3 | OR |

| 0.766 | All | ABC | Suburban | 2008 | 3 | OR | |

| 1.289 | All | All | Suburban | 2008 | 2 | OR | |

| 1.392 | All | ABC | Suburban | 2008 | 2 | OR | |

| Partial plus to partial interchange lighting | 1.036 | All | All | Suburban | 2008 | 3 | OR |

| 0.862 | All | ABC | Suburban | 2008 | 2 | OR | |

| 0.648 | All | All | Suburban | 2008 | 3 | OR | |

| 0.6 | All | ABC | Suburban | 2008 | 3 | OR | |

| Lighting on Surface Street Segments | |||||||

| Install lighting on surface street segments | 0.71 | Nighttime | KABC | N/A | 2008 | N/A | N/A |

| 0.8 | Nighttime | All | N/A | 2008 | N/A | N/A | |

| 0.63 | All | KABC | All | 2014 | 3 | FL | |

| 0.84 | All | O | All | 2014 | 3 | FL | |

| 0.68 | All | All | All | 2014 | 3 | FL | |

| 0.67 | Rear end | All | All | 2014 | 3 | FL | |

| 0.64 | Angle | All | All | 2014 | 3 | FL | |

| 0.72 | Single vehicle | All | All | 2014 | 3 | FL | |

| 0.72 | Other | All | All | 2014 | 3 | FL | |

| 0.68 | All | KABC | Urban | 2014 | 3 | FL | |

| 0.76 | All | O | Urban | 2014 | 3 | FL | |

| 0.74 | All | All | Urban | 2014 | 3 | FL | |

| 0.62 | Rear end | All | Urban | 2014 | 3 | FL | |

| 0.82 | Angle | All | Urban | 2014 | 3 | FL | |

| 0.63 | Single vehicle | All | Urban | 2014 | 3 | FL | |

| 0.82 | Other | All | Urban | 2014 | 3 | FL | |

| 0.89 | All | KABC | All | 2014 | 2 | FL | |

| 0.77 | All | KABC | Urban | 2014 | 3 | FL | |

| Improve street lighting illuminance uniformity | 0.977 | Nighttime | All | N/A | 2017 | 3 | FL |

| Countermeasure | CMF | Crash Type | Severity | Area Type | Year | Rating | State |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change average illuminance from 1 to X on surface street segments | X-0.0773 | Day time, Nighttime | All | N/A | 2017 | 3 | FL |

| Improve lighting illuminance and uniformity on surface street segments | Function of mean and standard deviation for horizontal illuminance | Other | All | Urban | 2019 | 3 | FL |

| Intersection Lighting | |||||||

| Provide intersection illumination | 0.67 | Angle | All | Rural | 2008 | 3 | GA |

| 0.56 | Pedestrian | All | Rural | 2008 | 3 | GA | |

| 0.881 | Nighttime | All | All | 2010 | 3 | MN | |

| 1.05 | Day time | All | All | 2012 | 3 | MN | |

| 0.92 | Nighttime | All | All | 2012 | 3 | MN | |

| 1.03 | Day time | All | Urban/subu rban | 2012 | 3 | MN | |

| 0.97 | Nighttime | All | Urban/subu rban | 2012 | 3 | MN | |

| 1.05 | Day time | All | Urban/subu rban | 2012 | 3 | MN | |

| 0.91 | Nighttime | All | Urban/subu rban | 2012 | 3 | MN | |

| 0.98 | Day time | All | Rural | 2012 | 2 | MN | |

| 0.98 | Nighttime | All | Rural | 2012 | 2 | MN | |

| 1.09 | Day time | All | Rural | 2012 | 3 | MN | |

| 1.07 | Nighttime | All | Rural | 2012 | 3 | MN | |

| Increase intersection illuminance from low to medium | 0.47 | Nighttime | Three leg | Urban | 2016 | 3 | FL |

| 0.48 | Nighttime | Four leg | Urban | 2016 | 3 | FL | |

| increase intersection illuminance from low to medium | 0.519 | Other | All | Urban | 2016 | 3 | FL |

| increase intersection illuminance from medium to high | 1.158 | Other | All | Urban | 2016 | 3 | FL |

| Install single luminaire at intersection | 0.29 | All, Nighttime | All | Rural | 2015 | 3 | MN |

| 0.79 | All, Nighttime | KABC | Rural | 2015 | 2 | MN | |

| 0 | All, Nighttime | O | Rural | 2015 | 2 | MN | |

CMF Development

A number of methods have been commonly used for CMF development (Carter, Srinivasan, Gross, and Council, 2012; Carter, Srinivasan, Gross, Himes, et al., 2012).

- Before-after with comparison group approach. This method considers crash and traffic changes irrelevant to the subject treatment by including an untreated control group for comparison. An important aspect of this method is the selection of a suitable comparison group. Hauer (1997) previously proposed a statistical method using a sequence of odds ratios to quantitatively measure the suitability of the control group. The before-after with comparison group method is considered more accurate compared to naïve before-after studies. However, it often cannot address regression to the mean as well as those using empirical Bayes.

- Empirical Bayes before-after approach. This method is similar to the before-after with comparison group method in that both draw information on the expected crash frequencies from a group of untreated sites. However, the empirical Bayes before-after method utilizes safety performance functions (SPFs) to account for crash changes due to traffic and potentially roadway changes over the study period. Using SPFs in this method, however, may not account for changes in traffic control or factors other than those considered in the SPFs over time that may affect safety and therefore the estimated CMFs.

- Full Bayes study. The full Bayes method is another approach to derive CMF information based on before- and after-treatment data. Compared to the empirical Bayes method, the full Bayes method allows the development of complex models that are more flexible and accommodative for smaller sample sizes. If developed properly, full Bayes studies can consider spatial correlation between sites. The method in some cases can result in more reliable CMFs compared to the empirical Bayes before-after method but in general requires more statistical skills.

- Cross-sectional approach. Cross-sectional studies are based on comparisons between safety data from sites with and without the subject treatment. This approach is particularly suitable for studies where before-treatment data is not available. In cross-sectional studies, different regression methods may be used based on the data to derive the crash ratios (i.e., CMFs) between sites with and without the subject treatment. Cross-sectional analyses can be difficult to control in some cases and require careful treatment to avoid bias caused by multivariate regression issues such as collinearity. Therefore, CMFs based on cross-sectional studies in some cases can be less reliable compared to before-after studies.

- Case-control approach. The case-control method is similar to the cross-sectional method in that it also uses data with and without the treatment. However, case-control studies model data around the outcomes (e.g., severity levels or crash versus non-crash). Case-control studies rarely develop CMFs that compare crash frequencies.

- Cohort studies. Cohort studies compare risks of a certain outcome between two well-controlled groups with and without the subject treatment. This approach is less common in safety studies since it is difficult to conduct such controlled experiments on real roadways to enable sufficient crash data.

Compared to many other safety treatments, roadway and street lighting systems are somewhat unique in nature because it is difficult to identify locations with both before-and-after data. In state and local jurisdictions that have a lighting policy, roadway and street lighting systems are typically installed during roadway construction or at a time historically beyond current institutional records, especially in urban areas. In states and localities that do not have a lighting policy, lighting is rarely used as a safety treatment either at the project level or systemically. For this reason, a cross-sectional approach is frequently more suitable for the development of CMF-based systemic lighting-related treatments (Gross and Donnell, 2011).

The CMF Clearinghouse currently uses a number of criteria to assess the quality of a CMF, including the study design, sample size, standard error, potential bias, and data source. Although most of these criteria can be relatively objectively controlled, the evaluation process is more or less subject to opinions (CMFClearinghouse.org). Currently, NCHRP 17-72 is developing a new CMF rating procedure that revises the 5-star rating scale to a 150-point score system where CMFs scored 100 and above may be considered high-quality CMFs worthy of inclusion in the second edition of the Highway Safety Manual (HSM) (Srinivasan, 2018). The new scoring system proposed consists of three broad quality evaluation areas including data (55 points), statistical analysis design (75 points), and statistical significance (20 points).

For before-after studies, the new scoring system requires studies to properly address issues such as regression to the mean bias, changes in traffic volume over time, suitability of reference/comparison groups, and quality of safety performance functions. For cross-sectional studies, the new system emphasizes aspects such as the similarity of sites with and without treatment, proper consideration of correlation between variables, and addressing of spatial and temporal correlations. Although on a different score scale, the new CMF scoring system is considered mostly consistent with the current star rating system when being applied to exiting CMFs in the current CMF Clearinghouse (Srinivasan, 2018). Note that neither scoring system takes into consideration geographic regions where data is collected and therefore does not account for transferability of the results. Accordingly, the rating/score of a particular CMF may not directly indicate its applicability for a specific location. For example, a 5-star fatal crash CMF developed based on European data may poorly reflect U.S. experience.

Roadway Lighting Safety and CMF Gaps

Based on the literature review, roadway lighting safety studies have shown conflicting results. While most studies revealed a positive safety effect for lighting, some showed insignificant or adverse effects of lighting on safety. The lighting CMFs included in the CMF Clearinghouse therefore also vary significantly within each treatment category. Many lighting CMFs were developed using cross-sectional analyses based on negative binomial modeling. Most such studies involved daytime crashes as an exposure measure in the form of night-to-day crash ratio, night-to-day crash rate ratio, or nighttime crash frequency weighted by daytime crashes. However, some focused on only nighttime crash frequencies most likely following the HSM methods for other safety infrastructure treatments. The project team also found the following gaps relevant to lighting CMFs:

The project team could not identify CMFs developed specifically for SSL systems. In addition, none of the CMFs compared different CCTs and/or different lighting sources.

- A number of studies used measured lighting data and therefore were able to analyze a number of detailed lighting variables. However, many studies only analyzed roadway lighting as a binary variable (i.e., with versus without), therefore ignoring the effects of different lighting performance metrics (e.g., illuminance/luminance levels and uniformity) on safety.

- The CMFs in the current CMF Clearinghouse covered intersection lighting, freeway interchange lighting, and surface roadway segment lighting. None of the CMFs however were for lighting systems on freeway continuous segments.

- The CMFs developed in domestic studies were rated between 2 and 3 stars. Most of the CMFs were based on data from single states.

CHAPTER 2

CMF Development

General Methods

A number of methods have been commonly used for CMF development: (Carter, Srinivasan, Gross, and Council, 2012; Carter, Srinivasan, Gross, Himes, et al., 2012; Gross and Donnell, 2011).

Before-After Comparison Group Approach

This method takes into account crash and traffic changes irrelevant to the subject treatment by including an untreated control group for comparison. An important aspect of this method is the selection of a suitable comparison group. Hauer (Hauer, 1997) previously proposed a statistical method using a sequence of odds ratios to quantitatively measure the suitability of the control group. The before-after with comparison group method is considered more accurate compared to naïve before-after studies. It, however, often cannot address regression to the mean as well as those using an empirical Bayes approach.

Empirical Bayes Before-After Approach

This method is similar to the before-after with comparison group method in that both draw information on the expected crash frequencies from a group of untreated sites. However, the empirical Bayes before-after method utilizes safety performance function (SPFs) to account for crash changes due to traffic and potential roadway changes over the study period. Using SPFs in this method, however, may not account for changes in traffic control or factors other than those considered in the SPFs over time that may affect safety and therefore the estimated CMFs.

Full Bayes Study

This method is another approach to derive CMF information based on before- and after-treatment data. Compared to the empirical Bayes method, the full Bayes method allows the development of complex models that are more flexible and accommodative for smaller sample sizes. If developed properly, full Bayes studies have the ability to consider spatial correlation between sites. The method in some cases can result in more reliable CMFs compared to the empirical Bayes before-after method but in general requires more statistical skills.

Cross-Sectional Approach

Cross-sectional studies are based on comparisons between safety data from sites with and without the subject treatment. This approach is particularly suitable for studies where before-treatment data is not available. In cross-sectional studies, different regression methods may be used based on the data to derive the crash ratios (i.e., CMFs) between sites with and sites without the subject treatment. Cross-sectional analyses can be difficult to control in some cases and require careful treatment to avoid bias caused by multivariate regression issues such as multi-collinearity. Therefore, CMFs based on cross-sectional studies in some cases can be less reliable compared to before-after studies. Due to the nature of crash data (i.e.,

over-dispersed, count-based, and non-negative), negative binomial regression is the typical analysis method for this approach.

Case-Control Approach

The case-control method is similar to the cross-sectional method in that it also uses data with and without the treatment. However, case-control studies model data around the outcomes (e.g., severity levels or crash versus non-crash). Case-control studies rarely develop CMFs that compare crash frequencies.

Cohort Studies

Cohort studies compare risks of a certain outcome between two well-controlled groups with and without the subject treatment. This approach is less common in safety studies since it is difficult to conduct such controlled experiments on real roadways to enable sufficient crash data for many reasons.

Lighting Specific Considerations

Compared to many other safety treatments, roadway and street lighting systems are somewhat unique in nature, as it is difficult to identify locations with both before-and-after data. In state and local jurisdictions that have a lighting policy, roadway and street lighting systems are typically installed during roadway construction or at a time historically beyond current institutional records, especially in urban areas. In states and localities that do not have a lighting policy, lighting is rarely used as a safety treatment either at the project level or systemically. For this reason, a cross-sectional approach is frequently more suitable for the development of CMFs based on systemic lighting-related treatments (Gross and Donnell, 2011).

One exception, however, is rural intersections. States and localities seldom use lighting systemically on rural roadways, yet lighting systems are sometimes used at the project level as a safety treatment (e.g., during the highway safety improvement process, or HSIP). In this case, it is possible to identify multiple locations where both before-and-after crash data is available for the development of lighting-related CMFs based on such locations. Because of roadway lighting’s use as a safety treatment at such locations, it is highly likely a safety analysis has proved the effectiveness of lighting beforehand. CMFs developed using these locations may not be applicable for other locations with distinctive characteristics.

With recent development of LED technology, some states have been replacing existing high-pressure sodium (HPS) systems with LED systems and/or installing new LED lighting systems during safety and new construction projects. This provides an opportunity for developing CMFs for the use of LED lighting systems using a before-after approach. For these scenarios, CMFs may be developed for either with-without LED lighting systems or HPS-LED safety comparisons.

Location Selection

The proper selection of study locations for lighting-related studies can be particularly challenging due to the different lighting practices at different states and local jurisdictions. To select sufficient and appropriate study locations, it is necessary to adequately address the following factors based on the type of CMFs to be developed:

Jurisdictional Policy Differences

When using study sites from different states or regions, researchers must carefully address the jurisdictional differences in lighting policies, driver populations, and traffic control and roadway design practices. Some states with no lighting policies do not own or maintain any lighting systems on the state

highway network. Other states, however, may use lighting excessively on certain roadway locations (e.g., urban freeways and principal arterials). Studies that include sites from both types of states may find their data to be dichotomous in presence of lighting consistent with the jurisdictional division. Note that different states also frequently have different practices in roadway and traffic control designs. Such a data set therefore may result in unwanted biases if not treated carefully.

Within Jurisdiction Use Where Considered Beneficial to Safety

Within some jurisdictions, lighting systems are frequently used where engineers believe there is a safety benefit. Following national and state lighting policies and guidelines, lighting needs are determined based on warranting factors such as site layout, crash history, traffic characteristics, and presence of non-motor vehicle users. The use of lighting is rarely random and requires awareness to properly account for these factors in study designs, particularly for cross-sectional analyses.

Continuous Versus Isolated Lighting

One characteristic of lighting unique from other safety treatments is the different visual reactions drivers have to continuous lighting and isolated lighting. When a driver enters a lighted roadway location, the human visual system needs to react and adapt to the different lighting environment. Driving behaviors during the transition period are therefore different from those in either unlighted or lighted environments. This factor may be addressed by either using sites with the same type of lighting or adding a binary variable identifying if a site is of a continuous lighting system.

Levels Designed to Meet Criteria

Lighting levels are a continuous variable designed to meet a set of criteria in the sense that illuminance and uniformity levels can be theoretically any value within a range between no artificial lighting and an over-lit system. Most lighting systems are designed to meet the national (i.e., Illuminating Engineering Society, and/or American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials) published recommended practice. Therefore, during site selection, it is common to have a dumbbell-shaped sample distribution over lighting variables (e.g., in terms of average illuminance, large proportions of the sites fall into either the 0–3 lux range that is known to be associated with non-designed light or the 8 lux and above range).

Analysis Area

Safety analyses of lighting systems frequently need to clearly define analysis areas to identify crashes associated with the studied lighting systems. Lighting studies frequently focus on site types, such as segments of freeways and non-freeways, intersections, mainline ramp locations, crosswalks (midblock or intersections), and parking lots/rest areas. For each type of site, analysis areas should be strategically defined taking into considerations such as drivers’ visual behaviors, lighting design areas, and data sample size.

Drivers’ Visual Behaviors

It is well known that roadway lighting systems not only affect drivers at the site that is lighted, but also as they approach a lighted site. Typically, a driver detects objects approximately 200 to 300 ft in front of the vehicle (Gibbons et al., 2015). This means that the lighting several hundred feet in front of the vehicle has an impact on the driver’s visual performance. For example, the lighting system at an isolated

intersection will not only affect the driver behaviors at the intersection, but also those of drivers approaching the intersection.

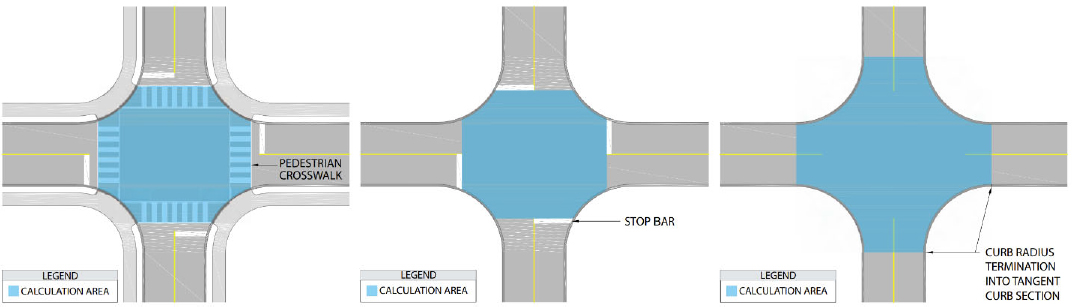

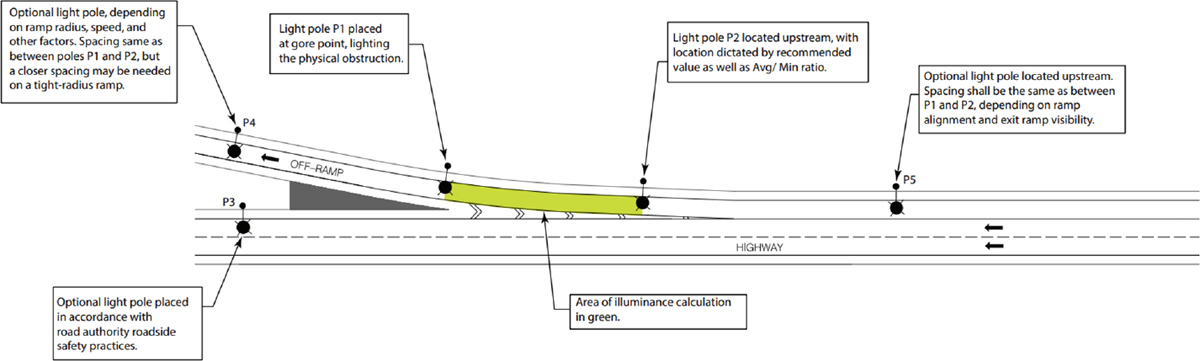

Lighting Design Areas

When designing roadway and street lighting, designers need to clearly define the design areas following applicable guidelines (American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO); Illuminating Engineering Society, 2022; Lutkevich et al., 2012). The lighting levels are designed to meet the applicable criteria within the design areas. For example, Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the lighting design areas at isolated intersections and freeway ramp locations, respectively. Some states may have additional guidelines on lighting design areas. For example, the Washington State Department of Transportation recommends a 200-ft design area for each luminaire at freeway interchange locations (Washington State Department of Transportation). The state also includes detailed recommendations on lighting design areas at intersections.

Homogeneous Roadway and Traffic Characteristics

There are factors many other safety studies routinely take into consideration as well. For example, when analyzing roadway segments, within each defined analysis area, the roadway and traffic characteristics ideally should be homogeneous enough so that driver behaviors and safety risks are better accounted for.

Safety Influence Areas of Sites

When conducting safety studies of point features (e.g., intersections and ramp junctions), it may be necessary to clearly understand the influence areas of such point features. For example, many studies use a 250-ft influence area for intersections. Depending on the location, size, and nearby access points, the area of influence may be adjusted to better reflect the site conditions.

Data Sample Size

Analysis areas that are small may result in fewer crashes identified within each analysis area. During safety analysis and CMF development, researchers need to design the study approach carefully to address all these factors. For example, to understand the safety effect of lighting at intersections, many researchers divide the intersections into the intersection box (bounded by stop bars on each approach or consistent with the intersection lighting design area) and intersection approaches.

Isolating Safety Impacts

Isolating the safety impacts of lighting during safety studies can be particularly challenging because, as previously stated, lighting is frequently installed at locations where it is most likely to benefit safety and it can be difficult to identify unlighted sites with similar conditions in the same region. Many agencies conduct warranting analyses when determining whether lighting should be installed at certain locations. Most such analyses take into consideration nighttime crash data as a primary factor. Without properly addressing the location selection issue, this practice results in an endogeneity issue (due to simultaneity of higher nighttime crash frequencies and use of lighting) for safety researchers analyzing lighting effects (Banks et al., 2014; Kim and Washington, 2006). If the lighting system cannot reduce nighttime crash frequencies to the level below that at locations without a nighttime safety challenge, improper cross-sectional analyses may lead to the problematic conclusion that lighting correlates with higher nighttime crash frequencies.

Statistical modeling techniques have been developed to address endogeneity issues. In the case of nighttime crash analysis, it is a fairly common practice for researchers to use daytime crash frequencies as a controlling method for evaluating safety treatment effectiveness during nighttime (Donnell et al., 2010). Such an approach assumes that lighting systems do not have any safety effects during daytime and therefore, separate daytime models involving the lighting variable would enable an estimate of the crash risks at subject sites in cross-section studies. This assumption, if not carefully controlled for, it does not take into consideration factors such as different safety issues during nighttime and daytime (i.e., shown by a relatively low correlation between nighttime and daytime frequencies at certain locations) and other roadway features functioning differently during reduced visibility conditions, such as, retroreflective delineation treatments.

To isolate the safety impacts attributable to lighting, studies should include variables describing the complexity of the study site as it pertains to crash risks. Examples of such variables include number of lanes, geometric alignment, presence of hazardous roadway features (e.g., turning lanes, merging lanes, and raised channelization), pavement marking conditions, and potential visual distractions in the background. In addition, studies should carefully consider key factors that help isolate lighting safety impacts, such as: average annual daily traffic and hourly volume, crash types, weather conditions, and traffic conditions.

Average Annual Daily Traffic and Hourly Volume

Depending on traffic condition, the lighting can potentially affect safety significantly in different ways. To correctly account for traffic conditions, average annual daily traffic (AADT) may be less significant in

a crash model. In such cases, it is necessary to use hourly volumes at the study sites to fully understand how lighting played a role in certain crashes.

Crash Types

Roadway lighting is considered to have different effects depending on the type of crash. For example, lighting is likely to have a greater effect on reducing fixed-object crashes than it does for multi-vehicle crashes. In addition, lighting may also help reduce nighttime crashes involving pedestrians and bicyclists. To isolate the effects of nighttime lighting, separate analyses should be conducted during daytime and nighttime hours. When roadway and traffic data become limited, it is also common for studies to use daytime crashes as a surrogate for safety conditions at the study sites.

Weather Conditions

Roadway lighting impacting safety during different weather conditions can be complex. Poorly designed lighting may perform counterproductively during certain weather conditions and/or when the windshield becomes dirty/wet.

Traffic Conditions

Due to the aforementioned factors, researchers may analyze crashes during different traffic and weather conditions separately. For example, crashes may be analyzed separately during non-peak hours and peak hours to identify the different safety effects during free-flow and saturated/congested traffic conditions.

Data Sampling and Collection

Sample Size Requirements

Sufficient sample sizes are an important requirement for CMF studies. In general, a rule of thumb is that the larger the sample size, the more reliable the CMFs developed for most, if not all, methods if. While some statistical methods allow the determination of sample sizes quantitatively, such methods require assumptions of crash distribution that are sometimes not necessarily accurate. For some CMF approaches (e.g., cross-sectional analyses), a sample size only turns out to be insufficient when the models do not show significant results for the subject variable (Gross et al., 2010).

To increase sample sizes for lighting-related safety studies, an obvious method is to identify more study sites. However, this approach may not be practical in many cases due to site availability and the fact that crashes are relatively rare events. Researchers routinely use multiple years of crash data to increase sample sizes. When using multiple years of crash data, it is also important to ensure that traffic patterns, roadway configurations, and traffic control at the study sites remained unchanged during the entire analysis period (AASHTO, 2014).

Lighting Performance Factors

It is also important to know that lighting performance may change over time. For example, the lighting levels of luminaires, including LED systems deteriorate over time due to luminaire performance, dirt accumulation, and the maintenance condition of the system. Therefore, designers create higher initial illuminance values for such systems and expect them to meet illuminance requirements after a certain length of time passes. Seasonal changes in roadside vegetation may also affect lighting performance over time. Such factors need to be considered when necessary if multiple years of crash data are used.

Field Measurement

Note that while current lighting systems, when designed to standard (some roadway/street lighting applications at certain agencies do not necessarily go through the design process), mostly follow the same recommendations outlined in Illuminating Engineering Society (IES) RP- 8 (various years) or the AASHTO Roadway Lighting Design Guide. The implemented lighting, however, can be significantly different from the computer-generated designs, and agencies rarely inspect lighting after the systems are installed. To accurately analyze lighting effects, researchers may need to conduct field lighting measurements to clearly understand lighting levels at the study sites. While luminance is a more useful measure from a design standpoint, this study targeted illuminance because it is a more reliable measure with which to conduct analysis.

CMF Types

Different types of CMFs may be developed for lighting based on various factors, such as:

Crash Types

Crash type examples include separate CMFs for single-vehicle crashes and multi-vehicle crashes.

Location

Location examples include CMFs for intersections, freeway ramp locations, and freeway segments. For intersections, researchers may develop separate CMFs for approaches and intersection boxes.

Lighting Variables

Many previous safety studies analyzed lighting as a binary variable (i.e., present versus absent). While this type of CMFs provides valuable information on the safety effects of lighting, it may not accurately quantify lighting effects due to the different safety performance of lighting systems at different illuminance, luminance, veiling luminance, surround ratio, and uniformity levels. As such, it may be of best interest to practitioners in some cases to use detailed lighting variables, such as minimum illuminance levels, average illuminance levels, and lighting uniformity levels. The increased implementation of LED systems (versus legacy HPS systems) currently also provides the safety community an opportunity to study the effect of correlated color temperature (CCT) of lighting systems on safety.

CHAPTER 3

CMF Development Examples

During this project, the team attempted to develop the following example lighting CMFs as examples for future development:

- Adaptive LED system: to replace traditional static HPS system in an urban setting for major and local roadways.

- Static LED system: to replace traditional static HPS system in an urban setting for major and local roadways.

- Increasing the horizontal illuminance of an LED system in an urban setting for major and local roadways.

The purpose of the CMF example development was primarily to illustrate the effects of different methods and consideration on the results of CMFs.

Lighting Systems Overview

The example CMFs were developed using crash and lighting data from the Cities of Cambridge and Somerville in Massachusetts. The City of Cambridge replaced the approximately 7,000 traditional HPS lights citywide on streets and parks during late 2014 and early 2015 with an adaptive 4000 K LED lighting system. With the new system, the light levels are dimmed to 50% of their normal brightness following a dimming schedule configured according to roadway types. This SSL system was one of the early adaptive systems across the nation, providing an opportunity to study the safety effects of adaptive LED lighting systems. During late 2015 and early 2016, the City of Somerville replaced citywide HPS roadway luminaires with a new LED system (U.S. Department of Energy, 2016). The Cities of Cambridge and Somerville are located side by side, sharing relatively similar roadway and traffic characteristics, providing an opportunity to evaluate both adaptive LED systems in the case of Cambridge, and a static LED system in Somerville.

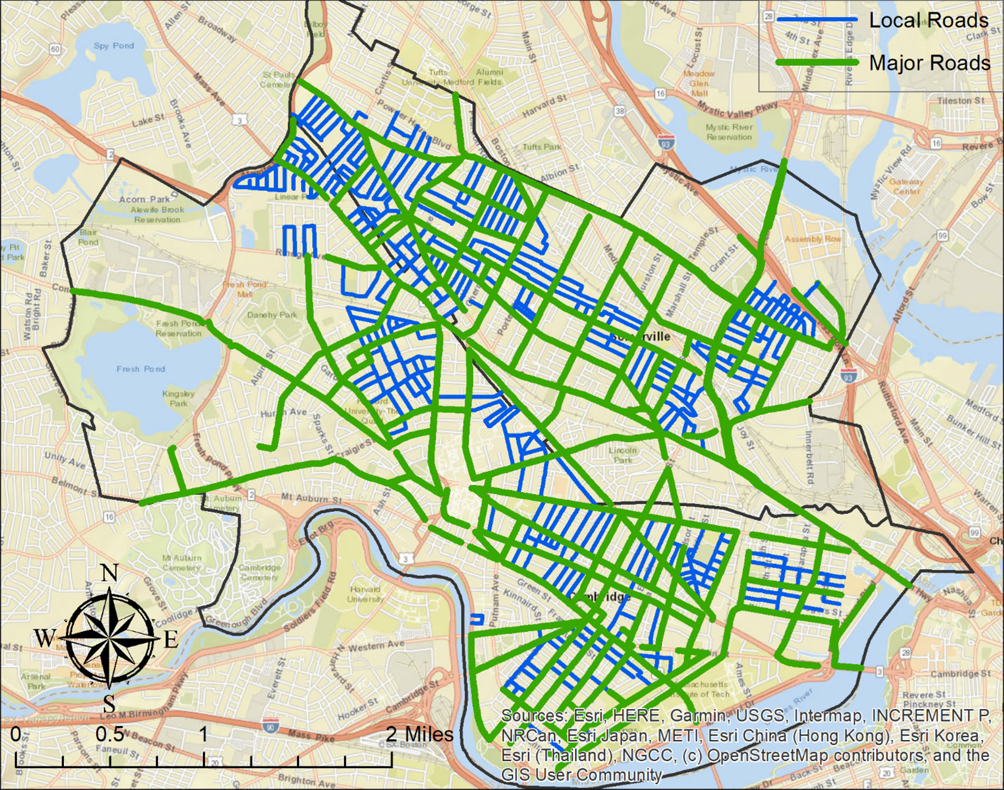

Roadway Segments Selection

The selection of roadway segments involved field lighting data collection for the purpose of identifying the potential safety effects of different lighting levels. The project team selected a number of roadways in both cities (Figure 3) that were representative of different types of roadways by land use (i.e., commercial versus residential) and AADT, referring to major surface roadways or classified by the Highway Performance Monitoring System (HPMS) roadways and local roadways. The Cambridge lighting system follows a dimming schedule based on three types of roadways: C1 roadways or major HPMS roads, C2 roadways consisting of smaller HPMS roads and major local roads, and C3 roadways that are minor local roads. The project team made an effort to ensure the selected roadways in Cambridge were representative

of all three types of roadways. The roadways in Somerville were also selected in a comparable manner. In total, the analyzed roadways included 46.6 miles of local roads and 64.6 miles of HPMS roadways.

This study was conducted using roadway segments. The roadway segments were defined for HPMS roadways as the continuous segments divided by each adjacent pair of intersections between HPMS roadways and for local roadways as the continuous segments divided by each adjacent pair of intersections of local and major roadways (excluding driveways). In total, this process resulted in 855 roadway segments including 332 HPMS segments and 523 local roadway segments.

Lighting Data Collection

The data collection effort was conducted from September 19–23, 2020, using the Virginia Tech Transportation Institute Roadway Lighting Mobile Measurement System (RLMMS). During data collection, the team traveled each selected roadway in the two cities with the RLMMS multiple times to measure lighting levels for all travel lanes. For roadways in Cambridge, the project team collected the lighting measurement data twice (prior to 10:00 p.m. and after midnight) to obtain both the normal and dimmed light levels.

The primary data of concern for this analysis was with illuminance, both horizontal and vertical, and luminance.

Crash and Roadway Data Collection

The project team obtained 2010–2019 crash data from the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT). Based on crash time and location, the project team determined nighttime (defined when the sun angles are below -6° in this study) crashes based on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) solar angle calculation method (Global Monitoring Laboratory).

For roadway and traffic variables, the project team collected the following information:

- AADT: collected based on 2010–2019 yearly HPMS submittals by MassDOT.

- Number of lanes: collected based on satellite imagery on ArcGISTM and Google® Maps.

- Speed limit: collected based on satellite imagery on ArcGIS and Google Maps. Note that most major roadways analyzed had a speed limit between 20 mph and 35 mph. In addition, many local roadways did not have speed limit signs posted. As a result, the project team did not include this variable in the modeling process.

- Sidewalk presence: collected based on satellite imagery on ArcGIS and Google Maps.

- Street parking presence: collected based on satellite imagery on ArcGIS and Google Maps.

- Bike lane presence: collected based on satellite imagery on ArcGIS and Google Maps.

- One way street indicator: collected based on satellite imagery on ArcGIS and Google Maps.

- Median presence: collected based on satellite imagery on ArcGIS and Google Maps.

- Land use type: included commercial, mixed, and residential; determined using GIS shapefiles published by the municipalities.

Methodological Considerations

For methodological considerations, the team collected information on both local and HPMS roadways in the two cities. For the demonstration of the CMF development process, however, the analysis mostly focused on HPMS roadways only. HPMS roadways are maintained by the state and had relatively complete

roadway/traffic information including yearly AADT data. The local roadways, however, had very limited roadway and traffic information, which considerably limited the use of more sophisticated modeling methods and therefore reliability of results.

During this study, the project team used yearly crash counts to increase sample sizes and take into consideration yearly crash trends. The use of yearly crash counts, however, resulted in multiple data points for each roadway segment, effectively making the data set a clustered sample (or panel data). Due to this design, the project team used mixed-effect negative binomial regression models for the analysis. While recognizing the randomness of yearly crash counts for individual locations, however, yearly crash counts also frequently exhibit a trend over time due to continuous changes in factors such as driving population, implementation of safer traffic control devices/designs, and increasingly available safety features in near vehicles. As such, the team introduced a year index variable, which is a continuous integer between 1 and 10 with 1 representing counts for 2010 and 10 for 2019.

Negative binominal regression is a regression technique that’s particularly suitable for over-dispersed count data (i.e., the variance is greater than the mean). Negative binominal regression has been widely used for crash data analysis (Donnell et al., 2010; Lord and Mannering, 2010; Yang et al., 2019). Negative binominal models with random effects are mixed models that are particularly useful in settings where repeated measurements are made on the same statistical units or where measurements are made on clusters of related statistical units (Bell, 2019; Donnell et al., 2010; Lord and Mannering, 2010). Mixed models address random effects (i.e., unobservable random variables) by including a random-effect matrix into the otherwise fixed models.

The project team used the SAS® software package for all statistical modeling during this study. The NLMIXED Procedure in SAS (SAS Institute Inc., 2015) enables a great deal of flexibility by allowing user programming to specify components, effects, and data distribution for regression with non-linear mixed models. To fit the mixed models, the SAS procedure maximizes an approximation to the likelihood integrated over the random effects. SAS uses adaptive Gaussian quadrature and a first-order Taylor series approximation for the approximation to the likelihood and a large variety of algorithms for the maximization. During the modeling process, SAS outputs the final maximized value of the log likelihood (-2 Log Likelihood) as well as the information criterion of Akaike (AIC), its small sample bias corrected version (AICC), and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). Different models for the same data sets can be compared by comparing the AIC, AICC, and BIC scores. Smaller scores of these measures indicate better fitted models.

Due to the non-linear nature of the optimization techniques used by SAS for mixed-effect negative binomial regression, the procedure sometimes fails to identify the global optimal when developing the mixed-effect models. In such cases, the project team used fixed-effect negative binomial regression models instead. To improve the SAS NLMIXED process, researchers first developed a fixed-effect model for all analyses and used the parameter estimates as the starting points for the NLMIXED optimization process. For most models, the mixed-effect models produced very similar parameter estimates compared to those of the fixed-effect models, possibly because the use of the year index variable reduced the randomness of yearly crash counts to be accounted for.

To calculate lighting effects on safety, researchers have suggested taking into consideration daytime crash experience for the same study sites (Donnell et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2019). Daytime crash experience would provide insights on the overall crash trend that has not been accounted due to the potential missing variables that are not considered in the nighttime models. The lighting CMF can be determined using the following equation:

Where:

- E (NLED) = expected nighttime frequency for the LED period;

- E (DLED) = expected daytime frequency for the LED period;

- E (NHPS) = expected nighttime frequency for the HPS period before LED conversion; and

- E (DHPS) = expected daytime frequency for the HPS period before LED conversion.

CMF Analysis Scenarios and Results

Replacing Traditional HPS Systems with an Adaptive LED System

Description of Treatment and Settings

This comparison analysis attempted to develop a CMF for the conversion of traditional HPS lighting systems to an adaptive LED system on major surface roadways in an urban area. The current lighting system is an adaptive LED system with a CCT of 4000 K that dims to half of its normal levels at midnight for major arterials (i.e., C1 roadways in Cambridge, MA) and 10:00 p.m. for minor arterials (i.e., C2 roadways in Cambridge MA). Prior to the LED conversion, the city had a legacy HPS system for citywide roadways. The CMF was developed based on mostly HPMS roadways in the City of Cambridge, MA whose lighting policy is that it illuminates all roadways in the city limit. This provides an opportunity for an ideal sample that does not include potential bias due to lighting used as a safety treatment following crash-based warranting analyses for many state-maintained roadways. The city also was one of the pioneers implementing an LED adaptive system in the early years, allowing sufficient before-and-after crash data for analysis.

Description of Data

The CMF was developed based on 246 roadway segments totaling 40.7 centerline miles in Cambridge, MA. The analysis involved a total of 13,820 daytime crashes and 4,080 nighttime crashes between 2010 and 2019 (Table 3). Based on the LED conversion schedule, crashes between 2010 and 2014 were used for the before (i.e., HPS) period and 2015–2019 crash data were used for the after (i.e., LED) period.

Table 3. Crash counts by year for the adaptive LED analysis.

| Year | Daytime Crashes | Nighttime Crashes |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 1,432 | 432 |

| 2011 | 1,404 | 502 |

| 2012 | 1,409 | 418 |

| 2013 | 1,435 | 394 |

| 2014 | 1,355 | 414 |

| 2015 | 1,267 | 419 |

| 2016 | 1,561 | 452 |

| 2017 | 1,315 | 373 |

| 2018 | 1,353 | 323 |

| 2019 | 1,289 | 353 |

| Total | 13,820 | 4,080 |

CMF Results for Adaptive LED System

Table 4 lists the mixed-effect negative binomial regression model for the Cambridge adaptive LED system based on nighttime crashes. Table 5 further lists the model developed based on daytime crashes for exposure measurement. Note that, while the LED indicator variable was significant (at a 0.05 level of significance) in the nighttime model, the same variable was not significant in the daytime model. Based on only the nighttime model, the CMF for converting a traditional HPS system to an adaptive LED system was determined as 1.14 (i.e., Exp (0.133)), suggesting a 14% increase in nighttime crashes after the LED conversion. Because the LED factor was not significant for the daytime crash model, it was not necessary to use the daytime crashes as an exposure measurement.

Table 4. Mixed-effect negative binomial model for nighttime – adaptive lighting, major roadways.

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard Error | t Value | Pr > |t| | 95% Confidence Limits | Gradient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | -1.064 | 0.171 | -6.21 | <.001* | -1.401 | -0.726 | <.001 |

| LED Indicator | 0.133 | 0.065 | 2.03 | 0.043* | 0.004 | 0.262 | -0.001 |

| Length (mile) | 2.515 | 0.372 | 6.76 | <.001* | 1.782 | 3.248 | <.001 |

| Year Index | -0.055 | 0.011 | -4.82 | <.001* | -0.077 | -0.032 | -0.003 |

| Log AADT | 0.230 | 0.038 | 6.00 | <.001* | 0.154 | 0.305 | <.001 |

| One way indicator | -0.459 | 0.105 | -4.36 | <.001* | -0.666 | -0.251 | <.001 |

| Sidewalk presence | -1.064 | 0.171 | -6.21 | <.001* | -1.401 | -0.726 | <.001 |

| Bike lane presence | 0.420 | 0.095 | 4.43 | <.001* | 0.233 | 0.606 | <.001 |

| Dispersion | 0.011 | 0.014 | 0.81 | 0.419 | -0.016 | 0.039 | 0.001 |

*indicates statistical significance (α=0.05)

Table 5. Mixed-effect negative binomial model for daytime – adaptive lighting, major roadways.

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard Error | t Value | Pr > |t| | 95% Confidence Limits | Gradient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | -0.136 | 0.131 | -1.04 | 0.301 | -0.393 | 0.122 | -0.004 |

| LED Indicator | 0.049 | 0.037 | 1.32 | 0.187 | -0.024 | 0.123 | -0.002 |

| Length | 2.860 | 0.277 | 10.34 | <.001* | 2.315 | 3.405 | -0.001 |

| Year Index | -0.014 | 0.006 | -2.15 | 0.033* | -0.027 | -0.001 | -0.019 |

| ADT | 0.115 | 0.023 | 5.07 | <.001* | 0.070 | 0.160 | -0.030 |

| One Way Indicator | -0.265 | 0.094 | -2.83 | 0.005* | -0.450 | -0.080 | -0.002 |

| Bike Lane Indicator | 0.259 | 0.070 | 3.73 | <.001* | 0.122 | 0.396 | -0.002 |

| Number of Lanes | 0.119 | 0.050 | 2.38 | 0.018* | 0.020 | 0.218 | -0.005 |

| Dispersion | 0.016 | 0.005 | 3.27 | 0.001* | 0.006 | 0.025 | -0.003 |

*indicates statistical significance (α=0.05)

Replacing Traditional HPS Systems with a Static LED System

Description of Treatment and Settings

This comparison analysis attempted to develop a CMF for the conversion of traditional HPS lighting systems to a static LED system on major surface roadways in an urban area. The current lighting system is a static LED system that maintains the full lighting characteristics throughout the entire nighttime. The City of Somerville converted the citywide HPS system to the current LED system during late 2015 and early 2016. The city lights all roadways within the city limits, providing a good opportunity to understand the safety effects of lighting.

Description of Data

The CMF was developed based on 137 roadway segments in Somerville, MA with a total length of 28.4 miles. The analysis involved a total of 5,721 daytime crashes and 2,041 nighttime crashes between 2010 and 2019 (see Table 6). Based on the LED conversion schedule, crashes between 2010 and 2015 were used for the before (i.e., HPS) period and 2016–2019 crash data were used for the after (i.e., LED) period.

Table 6. Crash counts by year for the Static LED analysis.

| Year | Daytime Crashes | Nighttime Crashes |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 679 | 227 |

| 2011 | 536 | 209 |

| 2012 | 626 | 238 |

| 2013 | 663 | 234 |

| 2014 | 580 | 195 |

| 2015 | 582 | 173 |

| 2016 | 608 | 233 |

| 2017 | 538 | 191 |

| 2018 | 462 | 171 |

| 2019 | 447 | 170 |

| Total | 5,721 | 2,041 |

CMF Results for Static LED System

Table 7 lists the mixed-effects model for the nighttime crashes for Somerville comparing the nighttime crash frequencies before and after the LED conversion for major roadways (i.e., HPMS roads). Table 8 further lists the mixed-effects model for daytime crashes for comparison. As the models indicate, the LED system was a significant factor in the nighttime model but not significant in the daytime model. Based on the nighttime model, conversion to an LED system was found to have a CMF of 1.22 (i.e., Exp (0.197)), suggesting a 22% increase in nighttime crashes after the LED conversion.

Table 7. Nighttime mixed-effects model for Somerville HPMS roads.

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard Error | t Value | Pr > |t| | 95% Confidence Limits | Gradient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | -1.737 | 0.489 | -3.55 | 0.001* | -2.704 | -0.771 | <.001 |

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard Error | t Value | Pr > |t| | 95% Confidence Limits | Gradient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LED Indicator | 0.197 | 0.088 | 2.24 | 0.027* | 0.023 | 0.370 | <.001 |

| Length | 1.937 | 0.001 | 0.30 | <.001* | 1.934 | 1.939 | <.001 |

| Year Index | -0.061 | 0.015 | -4.14 | <.001* | -0.090 | -0.032 | -0.001 |

| ADT | 0.253 | 0.041 | 6.18 | <.001* | 0.172 | 0.333 | -0.002 |

| One Way Indicator | -0.123 | 0.106 | -1.17 | 0.246 | -0.332 | 0.086 | <.001 |

| Sidewalk Indicator | -0.331 | 0.278 | -1.19 | 0.235 | -0.881 | 0.218 | <.001 |

| Bike Lane Indicator | -0.103 | 0.094 | -1.10 | 0.272 | -0.288 | 0.082 | <.001 |

| Dispersion | 0 | 0 | - | <.001* | - | - | - |

*indicates statistical significance (α=0.05)

Table 8. Daytime mixed-effect model for Somerville HPMS roadways.

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard Error | t Value | Pr > |t| | 95% Confidence Limits | Gradient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | -0.287 | 0.446 | -0.64 | 0.522 | -1.169 | 0.596 | 0.001 |

| LED Indicator | 0.006 | 0.057 | 0.11 | 0.911 | -0.107 | 0.120 | <.001 |

| Length | 1.476 | 0.344 | 4.29 | <.001* | 0.795 | 2.156 | <.001 |

| Year Index | -0.033 | 0.010 | -3.39 | 0.001* | -0.052 | -0.014 | 0.003 |

| ADT | 0.132 | 0.032 | 4.07 | <.001* | 0.068 | 0.196 | 0.005 |

| One Way Indicator | -0.124 | 0.103 | -1.2 | 0.231 | -0.327 | 0.080 | <.001 |

| Number of Lanes | 0.090 | 0.047 | 1.91 | 0.059 | -0.003 | 0.183 | 0.002 |

| Street Parking Indicator | 0.251 | 0.162 | 1.55 | 0.123 | -0.069 | 0.570 | 0.001 |

| Dispersion | 0.043 | 0.010 | 4.19 | <.001* | 0.023 | 0.064 | -0.003 |

*indicates statistical significance (α=0.05)

Increasing Horizontal Illuminance of an LED System

The adaptive lighting system at Cambridge provided an opportunity to analyze the correlations between different luminance levels and nighttime crash experience. Using the lighting measurement data, the project team attempted to understand this correlation for different types of roadways in the two cities during different time periods based on the diming schedule of the Cambridge system. For this analysis, the project team analyzed four lighting measures for three time period-roadway type combinations. The four lighting measures included:

- Average illuminance

- Minimum illuminance

- Maximum illuminance

- Standard deviation of illuminance (or variance)

The three time-roadway type combinations were:

- C1 roadways in Cambridge and HPMS roadways in Somerville for nighttime after midnight.

- C2 roadways in Cambridge and non-HPMS roadways in Somerville for nighttime after 10:00 p.m. and before midnight.

- All HPMS roadways in both cities for nighttime before 10:00 p.m..

The analyses used only crash data for the after-LED periods of the two cities.

During the analyses, the project team first attempted to develop mixed-effect negative binomial regression models. For those scenarios where SAS could not find a global solution for the random-effect models, the team developed fixed-effect negative binomial models instead. The analysis results did not show any significant correlations between the four lighting measures and nighttime crashes for the before 10:00 p.m. (HPMS roads) and the after 10:00 p.m. (C2 roadways) scenarios. The analysis of the C1 roadways for the after-midnight period did show that both mean horizontal illuminance and standard deviation of horizontal illuminance were significant for nighttime crashes. The results for the C1 roadway analysis, however, were based on regular negative binomial regression models after SAS failed to find a global solution for all four lighting variables for this scenario.

Table 9 and Table 10 list the negative binomial regression models for mean illuminance and standard deviation of illuminance, respectively, for the C1 roadways after midnight. As the models suggested, on the major roadways in both cities and after midnight, higher horizontal illuminance levels corresponded with lower nighttime crash frequency. In addition, more uniform lighting (i.e., lower illuminance variance) correlated with higher nighttime crash frequency. Holding all other variables constant, a 1 lux increase in mean illuminance correlated with a crash modification of 0.983 [i.e., exp (-0.017)], indicating a reduction of 1.7% in nighttime crash frequency. A 1 lux increase in illuminance standard deviation correlated with a 1.8% decrease in crash frequency (a CMF of 0.982 [i.e., exp (-0.018)]). It should be noted that these decreases in crash frequency are valid in the range of the mean illuminances and the standard deviations measured in the data. Crash frequency cannot be expected to decrease consistently with increases in illuminance and standard deviation of illuminance; this effect will plateau at a certain level of the illuminance variables.

Table 9. Negative binomial regression model for nighttime crashes after midnight – mean illuminance.

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard Error | Wald 95% Confidence Limits | Wald Chi-Square | Pr > ChiSq | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | -7.332 | 0.931 | -9.156 | -5.508 | 62.06 | <.001* |

| Mean Illuminance (Lux) | -0.017 | 0.007 | -0.030 | -0.004 | 6.91 | 0.009* |

| Cambridge Indicator | 0.727 | 0.122 | 0.488 | 0.966 | 35.50 | <.001* |

| Segment Length (mi) | 1.074 | 0.310 | 0.466 | 1.682 | 12.00 | 0.001* |

| Year Index | -0.253 | 0.042 | -0.335 | -0.172 | 37.17 | <.001* |

| Log AADT | 2.133 | 0.235 | 1.671 | 2.594 | 82.15 | <.001* |

| Number of Lanes | -0.140 | 0.045 | -0.227 | -0.053 | 9.86 | 0.002* |

| Dispersion | 0.309 | 0.083 | 0.183 | 0.521 | - | - |

| Sample size = 1080. Full Log Likelihood = -1041.01 *indicates statistical significance (α=0.05) | ||||||

Table 10. Negative binomial regression model for nighttime crashes after midnight – illuminance variance.

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard Error | Wald 95% Confidence Limits | Wald Chi-Square | Pr > ChiSq | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | -7.353 | 0.935 | -9.187 | -5.520 | 61.80 | <.001* |

| StDev of Illuminance (Lux) | -0.018 | 0.007 | -0.030 | -0.005 | 7.45 | 0.006* |

| Cambridge Indicator | 0.685 | 0.125 | 0.440 | 0.930 | 30.06 | <.001* |

| Segment Length (mi) | 1.180 | 0.307 | 0.579 | 1.782 | 14.80 | <.001* |

| Year Index | -0.252 | 0.042 | -0.333 | -0.171 | 36.78 | <.001* |

| Log AADT | 2.109 | 0.235 | 1.648 | 2.570 | 80.44 | <.001* |

| Number of Lanes | -0.108 | 0.045 | -0.196 | -0.019 | 5.69 | 0.017* |

| Dispersion | 0.309 | 0.082 | 0.184 | 0.521 | - | - |

| Sample size = 1080. Full Log Likelihood = -1040.83 *indicates statistical significance (α=0.05) | ||||||

CHAPTER 4

Discussion

During this analysis, the project team illustrated the development of CMFs for converting HPS systems to an LED system and for changes in LED lighting metrics. The first group of CMFs illustrated the safety implications of converting a traditional HPS system to an adaptive LED system and a static system in the Cities of Cambridge and Somerville, MA. For the changes in LED lighting metrics, the project team analyzed the correlations between four lighting metrics (average horizontal illuminance, maximum horizontal illuminance, minimum horizontal illuminance, and standard deviation of horizontal illuminance) and nighttime crashes.

When looking at the analyses for the individual CMFs, the results showed:

- A CMF of 1.14 was determined for converting a traditional HPS system to an adaptive LED system. This CMF was determined based on the crash and roadway data from the City of Cambridge, MA. For the analysis, the team used 2010–2014 crash data for the HPS period and 2015–2019 crash data for the LED period. This CMF seemed to suggest that the conversion of a traditional HPS system to the adaptive LED system in Cambridge correlated to a 14% increase in nighttime crashes.

- A CMF of 1.22 was determined for converting a traditional HPS system to a static LED system. This CMF was determined based on crash and roadway data in Somerville, MA. The analysis used 2010–2015 crash data for the HPS period and 2016–2019 crash data for the LED period. This CMF seemed to suggest that the conversion to the LED system coincided with a 22% increase in nighttime crashes.

- The LED conversion did not significantly correlate with an increase in daytime crashes during the same periods in either city.

- A CMF of 0.983 was determined for average horizontal illuminance for major HPMS roadways after midnight. This CMF seemed to suggest that a 1.7% of crash reduction correlated with each unit (i.e., lux) increase in average horizontal illuminance.

- A CMF of 0.982 was found for standard deviation of horizontal illuminance for major HPMS roadways after midnight, indicating a 1.8% decrease in nighttime crashes for each unit increase of horizontal illuminance standard deviation.

- Different lighting levels did not correlate with significant differences in nighttime crashes for HPMS roadways before 10:00 p.m. and for C2 roadways after 10:00 p.m.

Interpreting CMF Results for Converting HPS to LED

The previous analyses comparing the current LED systems with the previous HPS lighting showed that both cities with LED systems experienced an increase in nighttime crashes. The analyses, therefore attributed the increase in nighttime crashes to the LED conversion as the CMFs would imply. Note that the Cities of Cambridge and Somerville are located next to each other with comparable traffic patterns and driver populations.

LED systems are used increasingly for roadway and street lighting for several reasons, such as increased energy efficiency, more manageable performance variables (e.g., uniformity, distribution, and CCT), longer service life, and less maintenance. By looking at either system independently, a CMF that is greater than one (1.0) may appear plausible at first when considering the following factors:

- Lighting levels for the Cambridge system were dimmed too low later in the night for the adaptive system; and/or

- System-wide lighting design/installation issues are causing problematic uniformity or luminance levels.

Both factors may result in significant visibility challenges, causing risky driver behaviors. However, in this study, both LED systems that were implemented individually in the two cities were found with a CMF greater than 1 (1.0), which appeared to be highly unlikely. Both LED systems provide luminance levels comparable to that of the previous HPS systems at full level. Therefore, merely using LED instead of HPS should not result in significant changes in nighttime crashes. The crash changes, therefore, could be due to factors not considered in the models, such as increase of nighttime traffic in the region or change in nighttime crashes due to other factors.

The researchers plotted the average night-to-day (ND) crash ratios for the analyzed segments (Figure 5) to understand the crash trends over the analysis period. As the figure illustrates, the major HPMS roadways in Cambridge (i.e., C1 roadways) generally experienced increasing trends in ND crash ratios between 2012 and 2015, while the minor HPMS roadways in Cambridge (i.e., C2 roadways) experienced a dip between 2011 and 2015. The ND crash ratios for both types of roadways in general exhibited a declining trend between 2015 and 2018. Neither roadway types appeared to show an increasing ND crash ratio trend starting in 2015 after the LED system was implemented. Similarly, for the Somerville HPMS roadways, the ND crash ratios showed a decreasing trend starting in 2016, after the implementation of the new LED system. Prior to 2016, the ND ratio showed a dip between 2012 and 2016. These crash trends by no means suggest adverse effects of the LED systems on nighttime crashes. Note that the use of ND crash ratio in this discussion is appropriate, as the CMF analysis showed that the daytime crashes did not have a significant correlation with the implementation of the LED systems in either city.

The CMF modeling process for the LED conversion CMFs was a multivariate process involving, in particular, yearly ADT information. Taking into account the ADT development process at state DOTs, the yearly ADT information may be considered a particularly weak link in the CMF modeling process. States typically develop ADT values for roadways based on permanent and temporary traffic counts conducted at strategic locations. Such locations are frequently determined based on factors such as functional class and

level of traffic. Roadways positioned lower in this decision hierarchy, therefore, can sometimes have ADT predictions that are considerably biased from their actual values. In addition, the team did not obtain nighttime traffic counts for the CMF analyses.

Interpreting CMF Results for Lighting Levels

The study showed a CMF of 0.983 for horizontal illuminance, indicating that an increase of 1 lux in average horizontal illuminance was associated with a 1.7% reduction of nighttime crashes. In addition, a CMF of 0.982 was found for horizontal illuminance standard deviation, suggesting a decrease of nighttime crashes by 1.8% for each per-lux increase of standard deviation of horizontal illuminance. Note that both CMFs were only significant for major HPMS roadways after midnight.

While a mild crash reduction was found for increased illuminance levels, this does not necessarily contradict the purpose of the adaptive lighting system. The analysis was conducted for roadways in an urban environment with lower speed limits for the nighttime period after midnight. Most of the crashes analyzed were minor injury and property-damage-only crashes. Given the low number of such crashes after midnight to begin with, the decision to dim the lighting levels during this time period becomes a benefit-cost analysis situation.

These two CMFs were developed by comparing the crash data associated with different lighting levels of the two LED systems in Somerville and Cambridge. The analysis was based on a cross-sectional comparison between two cities next to each other. Compared to the CMFs for the LED conversion, these CMFs are believed to be more reliable. Note that the 1.7% crash reduction found for each per-lux illuminance increase is also comparable with the 2% range found in previous studies (18).

The fact that the different lighting levels did not significantly correlate with nighttime crashes for minor HPMS roadways and for the nighttime period before 10:00 p.m. is consistent with general observations based on past lighting research. The safety benefits of roadway lighting in the aspect of preventing motor vehicle (as opposed to pedestrian/bicycle) crashes tend to materialize in travel environments characterized by higher speeds, less traffic, and/or drivers unfamiliar with the roadways. The first two factors reflect the travel environment for major HPMS roadways in the two cities after midnight.

Other Discussion Points

Based on this study, the project team also offers the following discussion points:

CMF Method and Data Considerations

This study used before-after data for the safety effect analyses of the HPS-LED conversions in the two selected cities. For the safety analysis of the lighting metrics, however, the research team used cross-sectional data through a comparison of two lighting systems. As previously discussed, the before-after study used crash and traffic data spanning 10 years. The CMF results in the case appeared to be unreliable based on the team’s experience in lighting-related research. The analyses were likely biased due to significant temporal factors that were not adequately/accurately accounted for, such as yearly ADT changes, nighttime traffic patterns, driver population changes over time, and/or local developments that affect night traffic. The cross-sectional analyses, on the other hand, generated CMFs that were more reliable. For this reason, the CMFs developed from the cross-sectional analysis are the CMFs presented in this report.

This study demonstrates that for a before-after comparison analysis to perform well, analysts would need data that can relatively accurately depict the temporal changes of key factors such as traffic, roadway, and driving population. A traffic safety analysis that draws conclusions based on more years of data may not be as robust as one based on more study sites but fewer years of data. For cross-sectional studies, therefore, the use of more study sites is helpful provided that site selection is carefully performed to control factors

that affect lighting performance. When introducing “before” data as a control in cross-sectional analysis of lighting, it will also be necessary to consider the potential temporal changes that may affect safety over time.

This is particularly true for lighting studies, as roadway/street lighting often works as a secondary safety measure, the safety effects of which can be impacted by other factors. For example, factors such as the condition and availability of visual aids on roadways (e.g., lane markings and delineation or channelization devices), the roadway configuration, presence of roadway/roadside objects, and vegetation can all affect the safety effectiveness of lighting. Lighting at sites with different lane marking conditions, for example, can have significantly different safety effects. The frequently different conditions in such factors across various areas and/or jurisdictions can make site selection particularly challenging.

Interpretation of Lighting Safety Effects

Compared to many safety treatments that have clearly attributable safety effects (e.g., fixed-object crashes and safety barriers), understanding and quantifying lighting safety effects can be difficult in some cases. Findings purely based on quantitative data analyses may sometimes be misleading for users with limited expertise in lighting. Lighting affects traffic safety primarily by affecting drivers’ visual performance (acknowledging the introduction of lighting infrastructure on roadside potentially increasing fixed-object crash risks). Luminance levels, lighting uniformity, and color temperature of a lighting system can all affect a driver’s visual performance. Lighting systems of the same design may not necessarily be beneficial at all times and in all locations. The safety performance of lighting systems is potentially affected by factors such as luminaire and installation conditions, transition between locations of different illuminance levels, weather, and glare. Potential data issues not addressed in the analysis also further complicate the subject.

In this study, for example, the static LED system had a CMF higher than the adaptive system (i.e., 1.22 versus 1.14), possibly leading to the conclusion that reduced lighting levels are correlated with higher nighttime crash rates. The lighting level analysis later proved that this was not the case.

Use of Measured Lighting Data

Many previous lighting safety analyses used lighting presence data as a binary variable (i.e., present, or not present). This method has significant limitations since it does not consider the characteristics of different lighting systems. Accordingly, measured lighting data are in many cases a better option for a more thorough understanding of lighting effects on safety and driver behaviors. While using measured lighting data, however, analysts should understand that field lighting levels are a result of lighting systems designed to a recommended practice (most commonly the IES RP-8 standard or the AASHTO Lighting Standard). The lighting levels in the measurement data are generally not randomly distributed within the full range but instead tend to center around the recommended levels for designed lighting and a much lower level for non-designed lighting. In between these levels, values are limited and are generally due to reduced levels from distantly adjacent luminaires on the roadway or ambient light outside of the right of way.

Analyzing lighting based on design values, although not commonly, can be equally problematic. The characteristics of a lighting system on the ground can sometimes differ considerably from the original design based on factors such as installation, vegetation, ambient light, dirt accumulation on luminaires, and pavement conditions. Note that agencies rarely inspect lighting after systems installation. It is also a known practice that designers sometimes use luminaires that exceed the recommended levels to ensure the field values meet or exceed the required levels to avoid liability issues.

CHAPTER 5

Conclusions

The purpose of this investigation was to define the methods and potential pitfalls in the development of CMFs for lighting. Three examples are used to highlight these difficulties. In a study of lighting in Cambridge and Somerville Massachusetts, three sample CMFs considering the application LED lighting, adaptive lighting, and overall lighting level were developed. The results indicated that crashes increase with the application of LED lighting but less so when the lighting is adapted. However, this effect was countered by crashes being reduced when using a higher lighting level. Upon consideration, these three results contradict each other for the light level CMF. The lower light levels in adaptive lighting would create the expectation of more crashes than the higher light levels in the non-adaptive case but this was not what the analysis revealed. This highlights the difficulties in creating the CMF.

The analysis indicated that:

- More sites considered over fewer years of data collection may provide more reliable results, as other factors such as traffic volume and composition are less likely to change over a shorter timeframe.