Identifying Gaps in Sexual Harassment Remediation Efforts in Higher Education: Issue Paper (2025)

Chapter: Introduction

Introduction

Sexual harassment continues to be a persistent problem in institutions of higher education, despite the creation of new resources, policies, and programs aimed at combatting high rates on campuses (NASEM, 2018). Historically, these institutions have focused sexual harassment1 prevention and response efforts on complying with the requirements of the law (NASEM, 2018). Specifically, institutions in the United States have focused on responding to formal reports of sexual harassment through complying with Title IX and Title VII2—which prohibit discrimination against employees, students, staff, and/or faculty on the basis of sex—rather than identifying what harm has been caused by the sexual harassment, who has been harmed, and how that harm can be repaired. Even when institutions provide resources to repair the harm caused by sexual harassment, the harm might extend beyond the conclusions of the institutional response process and provision of the required remedial measures and sanctions (when applicable) (e.g., Grossi, 2017; Karp and Frank, 2016; McMahon et al., 2019; NASEM, 2018; Smith and Freyd, 2014). Put simply, there is a lack of attention to remediating (or repairing and limiting) the damage caused by sexual harassment across the timeline of the institutional response process (see Box 1 and Figure 1).

__________________

1 The 2018 National Academies report defines sexual harassment as consisting of three types of behavior: “gender harassment (sexist hostility and crude behavior), unwanted sexual attention (unwelcome verbal or physical sexual advances), and sexual coercion (when favorable professional or educational treatment is conditioned on sexual activity).”

BOX 1

Overview of the Typical Institutional Response Process

(see Box 2 for clarification of terminology use)

Educational institutions have broad discretion to develop policy and procedures to meet their obligations under Title IX and other federal, state, and local regulations and laws related to sexual harassment, making it difficult to describe a “typical” response process. However, there are a handful of key components that are common across most institutional responses to reports of sexual harassment. Throughout the paper we refer to this collection of key components as the institutional response process, which typically involves the following:

-

Disclosing and Reporting. An institution can formally learn of sexual harassment in many ways, including when a survivor makes a direct, formal report to an appropriate administrator (such as the Title IX officer or designee); a responsible employee/mandatory reporter shares information (that they learned about through an informal disclosure from someone like the survivor or a witness); or an incident is publicly reported.

- The officer will assess whether the individual and/or broader institutional community’s safety is at risk.

- Then, the officer shares information about campus resources, including confidential resources.

- Then, the officer will assess whether the allegations made in the disclosure—if substantiated—would constitute a policy violation within the institution’s jurisdiction. If the behavior does not fall within that policy or office’s jurisdiction (some Title IX offices serve students, staff, and faculty), the officer will connect the survivor to the appropriate office or individual. For example, the Title IX officer might connect the survivor to the Title VII office/officer, the office of civil rights/equal employment opportunity director, disability services, or student services or staff and faculty services, depending on the nature of the disclosure. Survivors may then meet or communicate with the relevant officer (often Title IX). The officer will provide general information about the individuals’ rights, the institutional response process (such as a description of what a formal investigation involves), and in the case of Title IX, discuss if any alternative resolution options are offered on campus.

-

Deciding About Next Steps. After speaking with the relevant officer, the survivor can determine whether they want to proceed with a formal report and investigation, simply access supportive measures, or take no action at all. Although the Title IX office may have a responsibility to pursue an investigation regardless, it typically tries to respect the wishes of the survivor.

-

Accessing Supportive Measures. Regardless of whether an investigation is pursued or a report would constitute a Title IX or Title VII concern, the institution will offer supportive measures. These could include a no-contact order; academic accommodations, modifications, support, or flexibility; counseling services; or other measures that do not require a finding of responsibility. Supportive measures can be implemented at any point in the response process, but are typically offered after an initial disclosure/report but before an investigation starts. Importantly, supportive measures must not be disciplinary or punitive in nature and in the case of Title VII, must not interfere with an institution’s ability to conduct its business purpose.

- If a formal report is made, then the accused individual will be notified, and as with the survivor, the officer will meet with them to offer supportive measures and share information about the formal response process, including investigations.

-

Accessing Supportive Measures. Regardless of whether an investigation is pursued or a report would constitute a Title IX or Title VII concern, the institution will offer supportive measures. These could include a no-contact order; academic accommodations, modifications, support, or flexibility; counseling services; or other measures that do not require a finding of responsibility. Supportive measures can be implemented at any point in the response process, but are typically offered after an initial disclosure/report but before an investigation starts. Importantly, supportive measures must not be disciplinary or punitive in nature and in the case of Title VII, must not interfere with an institution’s ability to conduct its business purpose.

-

Participating in a Formal Investigation or Alternative Resolutions.

- An investigation can contain many steps but may involve (1) interviews of the survivor, accused individual, and any witnesses; (2) evidence collection, review, and assessment of credibility; and (3) hearings (which can take place at different timepoints depending on the relevant regulation).

- In Title IX, there are many forms of alternative resolutions that involved individuals may wish to pursue instead of an investigation, such as reentry circles, mediation, and shuttle diplomacy. Both the survivor and accused individual must agree to participate in an alternative resolution before it can be employed, although importantly, the 2020 Title IX regulations prohibit the use of restorative justice and alternative resolutions in cases where the survivor is a student and the accused individual is an employee. Alternative resolutions may be sought at any point during the institutional response process, including mid-investigation.

-

Producing and Responding to the Final Outcome. Investigations typically result either in (1) a finding of a policy violation (where the accused is found to have violated a policy prohibiting sexual harassment) or (2) a finding of no policy violation (where the accused individual’s conduct is either found to have not violated a policy or risen to the level of violating a policy).

-

Communicating About the Results of an Investigation.

- In the case of Title IX, if the report was formally investigated, the findings are released to the survivor and the accused individual. In most cases, findings can be appealed by the survivor or accused individual.

- In the case of Title VII, due to protections around employee privacy rights, there is no requirement to let the involved individuals know the results of the investigation. For example, the survivor may not be notified of the finding if it resulted in disciplinary action for the accused individual (which would become part of the accused’s private employment records). However, some institutions may wish to notify involved individuals if it does not infringe on privacy rights and obligations.

-

Determining and Implementing Disciplinary Actions, Sanctions, and Remedies. Once any and all appeal options are exhausted and depending on the role of the accused individual in the institution (e.g., faculty, staff, student, contractor), different offices may be involved in determining and implementing disciplinary actions or sanctions.

- In Title IX, if a finding of a policy violation is reached, appropriate sanctions and remedial measures are determined and implemented, such as requiring the accused individual to take a leave of absence for a specific period and providing a no-contact directive for the survivor upon their return. Like the findings, sanctions are often able to be appealed by the accused individual.

- In Title VII, if a finding of a policy violation is reached, then appropriate and proportional corrective action consistent with institutional employment policies will be enacted (such as progressive discipline or education).

-

Communicating About the Results of an Investigation.

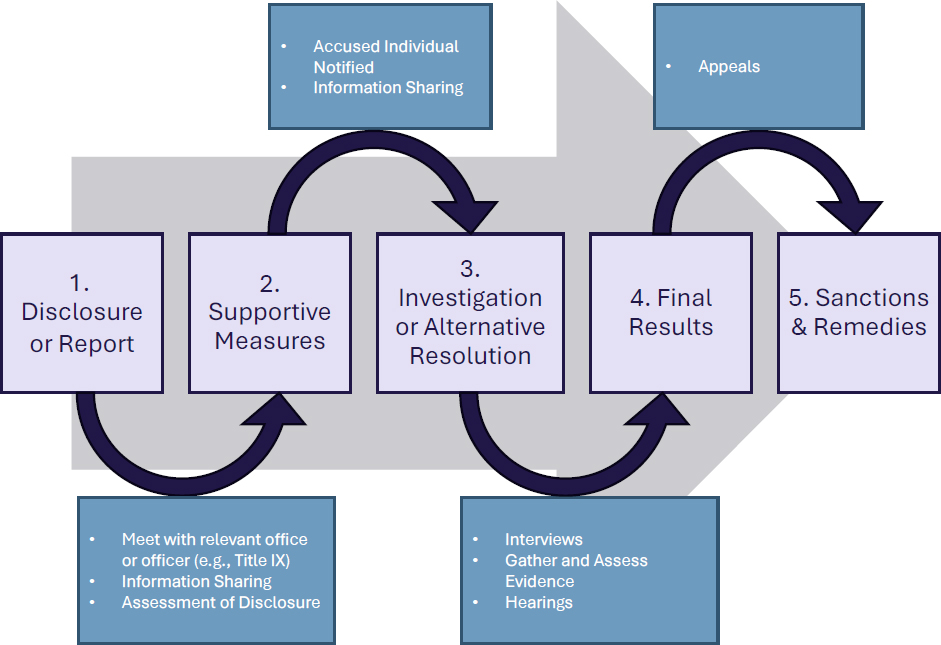

Figure 1 shows an overview of the steps described above and some of the intermediate actions and events that may take place between those steps.

Research shows that sexual harassment can cause harm to not only the survivor of sexual harassment but also the person accused of the harassing behavior and the community in which the harassment has occurred (see Box 2 and Definitions for a detailed description of the terminology used throughout this paper) (Koss et al., 2014; NASEM, 2018; Williamsen and Wessel, 2023). Given many institutions’ primary focus on compliance processes and relative lack of attention to addressing the harm experienced by different individuals as a result of the harassment, there is a pressing need for work that elucidates the resources that currently exist and the resources that are still needed to address that harm.

BOX 2

Definitions of Key Terminology

There are many terms people may use to refer to the individuals involved in an institutional response process. Each term may elicit different understandings of individuals’ experiences, can affect what resources are available to them, and may help or hinder efforts to remediate the harm that they have experienced. For example, the term “perpetrator” may communicate that, even before an institutional response process has determined whether a policy has been violated, the individual harassed someone and can only be responsible for causing harm, not experiencing harm themselves. By using the term “accused individual,” we retain the focus on the relevant facet of their experience (that they have been accused of sexual harassment) and the harms that may stem from those accusations. Similarly, we use the term “survivor” because “target” and “victim” can be disempowering, with the latter often associated with the criminal justice system (KMD Law, 2022). While some may associate the term “survivor” only with the most widely known forms of sexual harassment (such as sexual assault), we use the term to highlight how an individual may be harmed in experiencing any of the three forms of sexual harassment and how experiencing multiple instances of gender harassment can accumulate to the same negative effects as a single instance of sexual coercion (NASEM, 2018).

Each of these terms have benefits and drawbacks in different contexts, and which term an individual prefers to use to self-identify may differ from person to person. We have attempted to use the most accessible language in this paper that validates the experiences of the indicated individuals and highlights where harm may be occurring and necessitating remediation. Throughout this paper we use the following language:

Sexual Harassment (as defined in NASEM, 2018): a form of discrimination that consists of three types of harassing behavior: (1) gender harassment (verbal and nonverbal behaviors that convey hostility, objectification, exclusion, or second-class status about members of one gender); (2) unwanted sexual attention (unwelcome verbal or physical sexual advances, which can include assault); and (3) sexual coercion (when favorable professional or educational treatment is conditioned on sexual activity).

Survivor: the individual who directly experienced one of the three subtypes of harassing behavior that make up sexual harassment. (Note that we do not make any judgments as to whether the individual did in fact experience sexual harassment; the effects of believing oneself as having experienced sexual harassment are the focus in this paper.)

Accused Individual: the individual that has been accused of sexually harassing the survivor. (Note that we do not make any judgments as to whether the individual did in fact engage in harassment to the level of a policy violation; harms can occur regardless of the conclusion of investigations, and the effects of an accusation are the focus in this paper.)

Broader Institutional Community: the individuals affiliated with an institution, including faculty, staff, undergraduate and graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, administrators, and researchers (note that the level at which community is defined may shift in response to different contexts and remediation needs). This includes anyone who would receive communications about institutional processes or decision-making, or any individual who could witness and/or intervene in sexual harassment and who could in turn be affected directly or indirectly by the harassment. This also includes individuals charged with preventing and responding to sexual harassment, such as employees and administrators.

Disclosure: when an individual shares their experience of sexual harassment with anyone, often informally. This can include telling individuals who are not responsible for reporting that information to the institution, such as peers, non-supervisor coworkers, and confidential individuals (such as ombuds).

Report: when an individual (be that the survivor, a witness, or a responsible employee/mandatory reporter) formally tells the institution about an instance of sexual harassment.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s 2018 report Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine highlights the need to go beyond compliance and consider the ripple effects of sexual harassment (including gender harassment; see Footnote 1 above and Box 2). It emphasizes the multitude of negative effects on the survivor’s professional wellbeing (such as decreased job satisfaction, productivity, and performance) and their mental and physical wellbeing (such as increased rates of depression; post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD; and weight loss or gain). The report also details how sexual harassment has similar negative effects on the professional and personal well-being of others, such as individuals who witnessed the harassment (NASEM, 2018). Sexual harassment can also cause damage to an institutional community’s climate, as survivors and witnesses may mistakenly believe that unreported harassment has indeed been reported but that leadership is merely failing to respond (Fink, 2023; Harvard University, 2021). This may increase the perception that sexual harassment is tolerated and make university employees, as well as students and other community members, fearful for their safety (as depicted in one case in the United Kingdom where a student who had been criminally charged with domestic violence was still “under investigation” for the same incident at the institution several years later [Eccles, 2025]). Individuals accused of sexual harassment may also experience harm throughout the institutional response process. While the 2018 report did not examine these individuals’ experiences, the current paper addresses this gap, pointing to research on individuals who experience symptoms of PTSD after causing harm to others (e.g., Lathan et al., 2023). In this way, harm from sexual harassment compounds beyond the survivor and outside the boundaries of formal institutional responses to harassment, creating a need for institutions to go beyond mere compliance, investigation, and adjudication (NASEM, 2018).

Furthermore, if institutions only investigate reports as required by law but fail to address the harm caused, they may incur additional costs to their reputation and business. Sexual harassment is linked to increases in employee turnover and student attrition, decreased graduation rates, and potential legal liability, and it requires the institution to devote employee time and resources to responding to each claim (NASEM, 2018).

Some institutions have research, teaching, and public-service mission statements in their policies that affirm their commitment to broadening participation in higher education beyond mere legal compliance with prohibiting harassment and discrimination, but their lack of resources dedicated to remediating harm often undercuts those aspirations. In short, institutions may have both a business case and a mission-driven impetus to repair the damage caused to all parties affected by sexual harassment. With those discrepancies in mind, this issue paper answers two questions: What types of remediation efforts do higher education institutions already have in place to repair the harms incurred through sexual harassment, and what additional efforts are still needed?

The National Academies’ Action Collaborative on Preventing Sexual Harassment in Higher Education is a group of more than 50 academic research institutions that are working toward targeted, collective action on addressing and preventing sexual harassment across all disciplines and among all people in higher education. The four working groups (Prevention, Response, Remediation, and Evaluation) identify topics in need of research, gather information, and publish resources for the higher education community. Over the last 6 years, some of the collaborative’s member institutions provided examples of their remediation efforts, shaping the Remediation Working Group’s understanding of what efforts and resources institutions may already be using to remediate harm, and where gaps may exist.

Synthesizing research, case studies, and archival data from the Action Collaborative’s repository of novel work on the topic, this paper (authored by members of the Remediation Working Group) explores the harms that can occur as a result of sexual harassment at institutions of higher education, and the resources that exist to remedy those harms. Importantly, this paper is not a legal document and is not intended to examine all local, state, and federal laws, policies, codes, rulings, and regulations that are involved in responding when someone at an institution of higher education has disclosed or reported an experience of sexual harassment. Instead, the paper reviews how, at a high level, these laws, policies, and regulations may influence what the remediation of sexual harm can entail, including a brief history of how institutions have approached their remediation efforts in the past, followed by a discussion of the current landscape of efforts to assist various individuals harmed directly or indirectly by sexual harassment over the course of the institutional response process. This discussion organizes the review of existing efforts into a Remediation Efforts Matrix to help readers understand the timepoint- and role-based dimensions of this landscape, to support the efficient identification of resources that institutions can use to target specific populations on their campus for support/remediation, and to support institutional self-auditing and decision-making about how to better remediate sexual harassment–based harm. Sections on trends in efforts, remaining gaps, and remaining questions discuss patterns across the matrix as well as gaps in resources for specific populations at different timepoints (e.g., for the broader community after the institutional response process concludes). Throughout, the paper draws on the experiences and expertise that we have as institutional leaders, faculty members, Title IX coordinators, and researchers to inform our examination of remediating harm in higher education.

We hope that this paper serves as a resource for higher education administrators, practitioners, faculty, staff, and student leaders with the decision-making power and resources to help identify ways to remediate harm and thereby contribute to more effectively reducing and addressing sexual harassment. Specifically, the aim

of this paper is to help these individuals reflect on the current resources, policies, and programs that their institutions already have in place to remediate the harm that results from sexual harassment, and to identify areas that may need additional support. Through this self-audit, we hope institutions can begin to fill in those gaps in ways that provide more support and in turn more effectively prevent, respond to, and remedy sexual harassment.

What Is Remediation? A Brief History of Efforts to Address Sexual Harassment

There is no singular definition for the term remediation in the context of sexual harassment. In the context of environmental disasters, remediation can mean cleansing sites of toxic chemicals and dangerous debris after an accident (U.S. EPA, 2024) or returning land that has been contaminated by nuclear radiation to a state in which it can be used safely again (IAEA, n.d.). In the context of sexual harassment, this paper uses remediation to refer to programs, policies, practices, and services that have been designed to stop and repair the damage caused by sexual harassment and restore the harmed parties to an improved state. Based on social science and legal research summarized in the 2018 National Academies’ consensus study report, sexual harassment includes three subtypes: (1) gender harassment, the most common form, which includes verbal and nonverbal behaviors that communicate “insulting, hostile, and degrading attitudes” about a person on the basis of their gender; (2) unwanted sexual attention, which includes any verbal or nonverbal behaviors of a romantic or sexual nature that are unwanted (including sexual assault); and (3) sexual coercion, where a harasser suggests that an individual must accept their sexual advances to avoid negative professional or educational consequences.

Addressing Sexual Harassment Through Legal Compliance

Efforts to legally prohibit and address the effects of sexual harassment arose from a multitude of pressures coming to a head in the 1970s (Siegel, 2003). Feminist advocacy by and for survivors of sexual violence, pressures to increase women’s access to employment and education, as well as an expanding network of student health services for women and non-heterosexual students on college campuses increased attention to the topic of sex-based discrimination and harassment in education (Boschert, 2022). Key state and federal laws, policies, regulations, codes, and judicial rulings from this period addressed sex discrimination—including but not limited to Titles VII and IX—creating a complex tapestry of regulations that detail the legal basis for sexual harassment and what institutions of higher education are required to provide in their protections against and provisions for those who have experienced sexual harassment.

Institutions of higher education in the United States are currently guided by many local, state, and federal regulations, policies, and laws that inform how they must respond to reports of sexual harassment from students, faculty, staff, and/or employees (for a more in-depth review of those relevant to academia, see Chapters 2 and 5 of the 2018 National Academies report on sexual harassment). It is beyond the scope of this paper to address all such regulations, policies, and laws—especially as amendments, letters from federal agencies, and regulations themselves can be implemented and interpreted differently across different administrations (e.g., Title IX regulations of 2020 and 2024). However, understanding the promising

potential of remediation efforts that go beyond a compliance-based focus requires an understanding of what the baseline of compliance itself looks like. As such, we want to remind readers that this paper is not a legal document or complete review of the legal landscape on this topic, but instead we provide a brief discussion of how the tapestry of laws, policies, and regulations can support and sometimes complicate the remediation of sexual harassment-based harm. Below, we briefly highlight what is most relevant in our discussion of remediation that goes beyond compliance.

The federal-level foundations of legal protections against sexual harassment largely rest on Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 (Siegel, 2003; U.S. Department of Justice, n.d.-c; see Box 3 for a summary). Title VII prohibits discrimination against employees based on their “race, color, religion, sex, and national origin” (EEOC, n.d.) and “sexual harassment by interpretation and pregnancy by amendment” (NASEM, 2018). Importantly, this includes sex-based but non-sexual comments (e.g., those that denigrate a group’s intellect based on their gender) that can create a hostile work environment and constitute gender harassment (NASEM, 2018). Title IX, by comparison, prohibits educational programs or activities that receive federal funding from “discriminating against individuals on the basis of sex” (U.S. Department of Justice, n.d.-b).

Supplementing Title IX and Title VII are a host of other federal and regional regulations that affect how institutions may navigate investigating, communicating about, and remediating instances of sexual harassment on their campus. For example, the Clery Act requires institutions that receive federal funding to report crimes such as sexual assault that happen on or near campus (Clery Center, n.d.), increasing transparency around prevalence rates of this subtype of sexual harassment. On the other hand, the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 (FERPA; USED, n.d.) protects the privacy of students and may limit what information can be shared after the conclusion of an institutional response process, along with other privacy-protection laws such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA; CDC, n.d.). Finally, the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) similarly provide privacy protections for individuals making use of leave and accommodations (NASEM, 2018; U.S. Department of Justice, n.d.-a; U.S. Department of Labor, n.d.).

Regional regulations can also complicate the picture. For example, in 2023 the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals (a federal court with jurisdiction in Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin) upheld a prior 2017 judgment and ruled that Title IX provides protection for transgender students (individuals who do not identify with the sex they were assigned at birth) (A.C. v. Metro School District of Martinsville; Goodman-Williams et al., 2024). Yet in January 2025, the Department of Education stated that Title IX will enforce that one’s sex is unchangeable (interpreted as meaning Title IX does not provide protection for individuals who do not identify with the sex they were assigned at birth, or transgender individuals), revealing one instance of contradicting regulations (USED, 2025). Further reflecting the complexity of navigating processes around experiencing and addressing sexual harassment, in 2020 the Supreme Court ruled that Title VII protects transgender individuals from employment discrimination (Bostock v. Clayton County). Finally, beyond discussions about who is protected under Title IX, issues of transparency and communication can be complicated at different levels of governance. State laws about public record-keeping by public institutions may affect transparency about a given case, such as in Tennessee, where

BOX 3

Key Federal-Level Regulations, Policies, and Laws for Addressing Sexual Harassment

Title IXa: Prohibits educational programs or activities that receive funding from the federal government, from excluding individuals from those programs or activities based on sex. Is often discussed as relating mainly to the experiences of students but can involve any individual that is a part of the institution, including staff, faculty, and employees.

Title VIIa: Prohibits employers from discriminating against employees (or potential employees) based on the legally protected classes of race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. Judicial interpretation and amendments have expanded Title VII’s reach to include protection from discrimination if one is pregnant and from sexual harassment.

FERPA (Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act): Dictates under which conditions educational agencies or institutions that receive funding from the federal government can or cannot share student records (e.g., grades, financial records, disciplinary actions). (USED, n.d.)

Clery Act: Requires educational institutions that receive federal funding to share a report every year detailing statistics on the past 3 years’ worth of crime (including but not limited to sexual harassment-related crime) on and near campus, as well as what the institution has done to improve safety on campus. (Clery Center, n.d.)

HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act): Dictates under which conditions sensitive health information (such as diagnoses, medical claims, and referrals) can be disclosed to other individuals/institutions with and without the individual’s consent. (CDC, n.d.)

FMLA (Family and Medical Leave Act): Provides employees who meet certain conditions to take up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave each year to attend to family and personal medical concerns (e.g., pregnancy, caretaking for a seriously ill spouse, recovering from a condition that affects their ability to perform their essential job functions). Also provides privacy in the sharing and storage of medical files. (U.S. Department of Labor, n.d.)

ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act): Prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities that substantially limit one or more major life activities (e.g., speaking, working, standing). Also provides privacy in the sharing and storing of medical files. (U.S. Department of Justice, n.d.-a)

a Title IX, also known as the Education Amendments of 1972, 20 U.S.C. §§ 1681–1688, and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, P. L. 88-352, as amended, 42 U.S.C. 2000e.

open-access rules require the results of a Title IX investigation to be publicly posted (TN Code § 10-7-504). In short, the combination of federal, state, and local regulations creates “an array of competing and sometimes contradictory obligations that may hamper transparency and effectiveness [of efforts aimed at combatting sexual harassment in institutions of higher education]” (NASEM, 2018).

As stated before, however, Title IX and Title VII may loom largest in an institution’s process for responding to reports of sexual harassment, revealing a primarily compliance-focused (rather than healing-focused) approach. In particular, given that (1) institutions often have a single individual or office serving multiple

relevant roles (such as their Title IX coordinator and the Equal Employment Opportunity officer) (e.g., Siena College, n.d.; University of Kansas, n.d.) and (2) Title IX often has stricter standards and rules for investigating reports, many institutions first examine if reports fall within Title IX and then refer reports to other offices only when necessary (U.S. Department of Justice, n.d.-b). Due to this common deferral, throughout the rest of the paper we will generally focus on the Title IX process, noting where other processes diverge and other legal limitations arise that might affect remediation efforts (such as in releasing the findings of an investigation into an employee’s behavior).

For example, while Title VII does not, Title IX requires institutions to designate an employee to receive reports of sexual harassment and to notify students, faculty, and staff of this report filing process; to investigate these claims through an impartial, “prompt, and equitable” grievance procedure; to notify all parties involved of its conclusions; and to take “remedial” action (used in the legal sense and not in the sense defined at the outset of the What Is Remediation? section) to prevent the harassment from continuing and correct any of its discriminatory effects (USED, 2001). It is important to acknowledge that Title IX is an administrative process that is meant to protect the procedural and substantive due-process rights of the involved individuals, and that it is framed around an institution’s regulatory obligations. Indeed, many related policies are designed around a risk mitigation/legal compliance framework rather than a harm-reduction framework. Put more simply, the primary focus of the Title IX and Title VII processes is not how to support the healing of involved individuals but to determine what the institution’s responsibilities are regarding the reported conduct (which may still include stopping harm and correcting any discriminatory effects if an investigation finds that a policy has been violated). Acknowledging this tension between legal compliance and harm reduction may help explain the need for and gaps in remediation efforts, as we detail throughout the paper.

However, even as Title IX offices in the last 10 years have sought to implement more trauma-informed processes, become more responsive to survivors’ needs, and increase transparency regarding investigations and the adjudication of reports, academic institutions have struggled to address sexual harassment in ways that effectively reduce its prevalence and prevent its recurrence (Ahmed, 2021). Title IX is framed around a two-person dyad (which has been reaffirmed through federal regulations and judicial rulings) of a complainant (the survivor) and respondent (the accused individual). This dyad reflects a quasi-judicial framework that has been criticized by victim advocate organizations, such as Know Your IX and End Rape on Campus (McDaniel and Gomez, 2023), as well as advocates for those accused of sexual harassment (Miltenberg, 2019). Such an approach may reflect institutions’ punitive (rather than restorative or rehabilitative) approach to addressing student misconduct more broadly (Karp and Frank, 2016). In addition, many institutions fail to meet the baseline requirements for compliance with Title IX, posting incomplete policies for how to report sexual harassment or failing to post the policy publicly at all (NASEM, 2018), which may impede individuals’ access to remediation efforts. Further, Title IX has not been completely successful at identifying and addressing gender harassment (as opposed to sexual assault), and doing so in ways that recognize the complex professional and educational dynamics of sexual harassment in all the ways it can harm lesser-studied populations such as faculty, staff, graduate students, and postdoctoral scholars (Cipriano et al., 2022; Minnotte and Pedersen, 2023). These individuals may, in turn, also experience challenges in accessing remediation efforts.

Finally, the limitations of this complainant-respondent dyad, as well as changing standards across different administrations for what constitutes sexual harassment as defined by Title IX, have also shaped the limited attention and resources typically devoted to a wider range of sexually harassing behaviors (including those that might not rise to the level of a policy violation or meet the standards necessary for formal investigation). For example, comparatively fewer resources are focused on addressing comments containing gender stereotypes and how they might rise to the level of a policy violation than on responding to sexual assault or coercion (Huhtanen, 2022). In addition, if an institution takes a purely compliance-focused approach to addressing sexual harassment, then it is only required to provide remedial measures if a Title IX investigation finds that a policy prohibiting sexual harassment has been violated. This is troubling, given that many instances of sexual harassment do not meet the high legal bar for what constitutes sexual harassment (NASEM, 2018). As a result, institutions addressing only the harms that would meet this high bar means that most survivors’ harms would not be remediated at all. Importantly, research shows that instances of harassment that do not rise to the level of a policy violation can accumulate and escalate into more severe forms of harassment or contribute to the development of a hostile environment when left unaddressed (NASEM, 2018). By employing a compliance-focused rather than remediation-focused framework for responding to sexual harassment, institutions of higher education miss out on the opportunity to address harms that occur frequently and intervene before they compound to create larger problems in the future.

Addressing Sexual Harassment Through Restorative Justice

A remediation-based approached to sexual harassment goes beyond the compliance-based approach of addressing harmful behavior that only rises to the level of a policy violation. Instead, it works toward addressing and repairing the damage that was caused by the sexual harassment (including harm incurred during the institutional response process itself), regardless of compliance-based determinations of the severity of the harassment. An important consideration in this approach is that sexual harassment produces multiple negative effects, not only on the survivor but also on the accused and individuals in the broader institutional community. For example, even after a case is resolved, the individuals who are or were in the same laboratory, department, or classroom as the survivor may experience continuing effects of the harassment (sometimes called misconduct) or the institution’s response. Remediating sexual harassment addresses these effects and seeks to restore individuals and communities to a more supportive environment and climate. Further, remediation goes beyond the conclusion of a formal institutional response process to focus on addressing the negative effects that the alleged harassment (and institutional response process itself) may have on both survivors and accused individuals, regardless of the specific findings made by the institution (Koss, 2014).

One primary way that institutions have sought to do this when a report is brought to Title IX is through the provision of alternative resolution processes, including restorative justice. The term alternative resolution refers to any process that does not involve a formal Title IX investigation (note that the 2020 Title IX regulations allow for alternative resolution processes to take place in certain cases). Alternative resolutions may involve shuttle diplomacy, conferencing, mediation, arbitration, restorative justice processes, or any other course of action to which all parties agree (note, however, that restorative justice is prohibited in Title IX cases where the accused individual is an employee and the survivor is a student). While there is some overlap among different approaches, restorative justice processes emphasize repairing harm and holding those who caused harm

accountable in a non-adversarial manner, rather than focusing merely on meeting institutional regulatory obligations.

In contrast to the criminal justice system, which focuses on the accused individual, the laws potentially broken, and the minimization of risk to the institution, alternative resolution processes like restorative justice ask who has been harmed, what the needs of those harmed are, and how the causes of the harm can be addressed (James and Hetzel-Riggin, 2022). Restorative justice has deep historical roots in the practices of indigenous peoples of North America and New Zealand (particularly the practice of community circles). The modern movement first took hold in the 1970s and 1980s in Canadian religious communities and New Zealand family courts; it sought to resolve criminal conflict through circles and conferences that empowered survivors and accused individuals together to determine restorative pathways. It was influenced significantly by innovative programs like the Yukon’s peacemaking circle model that reshaped justice reform across North America (CBC, 2022).

In addition to restorative justice practices spreading in criminal justice, juvenile justice, community service, and educational settings over the last few decades, they have been leveraged as a mechanism for navigating social and political conflict, such as through South Africa’s 1996 Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Lin, 2005). Indeed, a majority of U.S. states now have legislation that encourages the use of restorative justice as part of their justice system (Beitsch, 2016). In addition, many universities offer courses in restorative justice, and several have graduate programs in restorative justice (e.g., the University of San Diego’s Master of Arts in Restorative Justice Facilitation and Leadership). Notable in this growing field of various approaches to training and certification in restorative justice have been ongoing ethical concerns about the institutional appropriation of indigenous practices, in which a desire for broader recognition and application of restorative justice principles exists in tension with the dangers of cultural appropriation (e.g., the use of “talking sticks” outside of Native American contexts; Cirioni, 2021).

Although applications of restorative justice theory have been slower to germinate in institutions of higher education, the use of its principles in student conduct procedures has been increasing in recent years, along with an expansion in research into the effectiveness of this approach (Karp, 2023). Such approaches can include those that honor, support, and reintegrate individuals affected by sexual harassment (including accused individuals and the broader institutional community). Honoring people can involve intentionally listening to their experiences and recognizing and acknowledging the sacrifices they made and the harm they experienced, such as from different types of retaliation, character assassination, and stigma and harassment associated with whistleblowing (e.g., Lim et al., 2021). Supporting these individuals can involve providing dedicated resources (e.g., faculty-led services and access to third-party counseling or support) and trained personnel (e.g., organizational ombuds) to address harms in workplaces and learning environments. Reintegration can involve any intervention that supports the needs of individuals affected by sexual harassment following an investigation and/or finding of a policy violation (or even when the investigation finds that no policy was violated), including not only the individuals directly involved in an investigation but also the broader communities to which those individuals may return (such as their labs, social clubs, or departments).

Studies examining the early adoption of restorative justice revealed that alternative sanctions classified as “reintegrative sanctions” (such as apology and community service) produced greater satisfaction and lower recidivism rates among student participants than traditional sanctions (Gallagher Dahl et al., 2014; Karp and Conrad, 2005; Karp and Sacks, 2014). Initial research also shows that survivors find restorative justice to be a beneficial approach, or in the case of community members, believe it could be (Marsh and Wager, 2015; McGlynn et al., 2012; Wager, 2012). The implementation of restorative justice mechanisms in cases of sexual harassment was delayed in part by guidance contained in the Department of Education’s 2011 “Dear Colleague” letter,2 which opposed the use of mediation in sexual assault cases (Ali, 2011) and created confusion about whether restorative justice processes were prohibited from use (Orcutt et al., 2020). In 2017, the Department of Education released a letter that explicitly addressed the use of informal resolution processes and stated that they were permitted, provided that all parties voluntarily participated (USED, 2017). However, given that this letter was guidance but not a formal regulation, confusion remained among administrators. As a result, restorative justice has only recently begun to gain traction in higher education settings, and evaluation of the efficacy of restorative justice efforts in higher education is relatively rare (see Karp, 2023; Marsh and Wager, 2015; McGlynn et al., 2012; Wager, 2012). However, prior work by researchers in this area has prompted U.S. universities to consider incorporating restorative justice practices into their procedures, based in part on the advocacy work of the Campus PRISM (Promoting Restorative Initiative for Sexual Misconduct) Project, coordinated by the Skidmore College Project on Restorative Justice (see the discussion in Karp et al., 2016).

As detailed in Karp’s 2019 The Little Book of Restorative Justice for Colleges and Universities, restorative justice practices in circling and restorative conferences can be key to a whole-campus approach that prepares an institution to strengthen its community, respond to conflict, and support reentry of harmed and offending individuals. It is this comprehensive aspect of restorative justice—across affected individuals and communities, as well as across the life of an incident—that makes it an appropriate framework for centering remediation in the institutional response to sexual harassment. However, as this is a burgeoning area of work, there has yet to be a robust evaluation of the effectiveness of using restorative justice practices to address sexual harassment in higher education across different levels of community. For example, there has not yet been an examination of the efficacy of restorative justice when used to address harm in large units (such as colleges) compared to smaller units (such as labs). There is also yet to be an examination of how different remediation approaches might address or be better suited for sexual harassment cases of varying severity, including those that do not rise to the level of a policy violation. For example, shuttle diplomacy may not be well suited to address a widely publicized case of sexual harassment that is well known in the broader community (i.e., across an entire department rather than just within a singular laboratory), while another approach could be more effective (such as a reentry circle). Our analysis reflects the current lack of evaluation and points instead to promising practices and examples.

__________________

2 Dear Colleague letters are used by federal agencies (such as the Department of Education) to communicate information and/or provide guidance broadly to the public, such as providing clarity on an administration’s interpretation of Title IX regulations. For example, the 2011 Dear Colleague letter was interpreted as guiding institutions of higher education to use the lower bar of a “preponderance of proof” in investigating sexual assault cases. This letter was then withdrawn in 2017, and the new letter was interpreted as letting individual institutions decide whether to use the “preponderance” bar or the higher, “clear and convincing evidence” bar (among other guidance) (Kosanovich Dickerson, 2017).

With this understanding of how institutions of higher education have traditionally approached responding to sexual harassment (namely, through compliance with regulations), what constitutes remediation, and what burgeoning areas of work such as restorative justice may support institutions’ efforts to prevent and address sexual harassment, we now discuss the harms that a remediation-focused approach can address.

When and for Whom Is Remediation Needed?

Research shows that a compliance-focused response to reports of sexual harassment is not sufficient to repair the harm done to individuals and communities (NASEM, 2018). Specifically, it shows that a compliance-focused response fails to account for harm experienced by the survivor before the harassment is reported to the institution (Griffin et al., 2022), during the institutional response process (Smith and Freyd, 2014), and after the institutional response process has concluded (Bergman et al., 2002). As part of our examination of the gaps that exist in remediation efforts, we first reviewed and synthesized the research that identifies these harms in more detail—in essence, identifying when and for whom remediation is needed.

Definitions

Before detailing the harms that are occurring at specific points in the timeline of the institutional response process, we want to clarify our use of terminology throughout this paper (see Box 2 for our rationale). As a reminder, the term sexual harassment refers to the three subtypes of harassment described in the 2018 National Academies’ consensus study report: gender harassment, unwanted sexual attention, and sexual coercion. The term survivor refers to the individual who directly experienced sexual harassment. While some may associate that term more closely with individuals who have experienced sexual violence (such as sexual assault), research shows that instances of seemingly minor gender harassment can significantly harm individuals, particularly if such instances are part of a pattern of behaviors that accumulate into hostile levels (NASEM, 2018). In line with this reasoning, it is used in this paper to succinctly refer to an individual who has experienced any of the three subtypes of sexual harassment. Throughout this paper the term accused individual is shorthand to refer to the person that has been accused of sexually harassing the survivor. With this terminology, we do not make any judgments as to whether the survivor experienced and the accused individual did in fact engage in harassing behavior at the level of a policy violation; harms can occur regardless of the conclusion of investigations. Instead, the effects of an accusation are the focus in this paper. Broader institutional community refers to the individuals affiliated with an institution, including faculty, staff, undergraduate and graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, administrators, and researchers. Anyone who would receive communications about institutional processes or decision-making, or any individual who could witness and/or intervene in sexual harassment is a community member who could in turn be affected by the harassment even if they were not directly involved in the incident. Importantly, we use the term flexibly, as depending on the context and specific circumstances, it may be more useful to define community at different levels (i.e., at the lab level, at the department level, or at the institution-wide level).

We also want to define our framework for understanding each of these group’s potential harms—specifically, our multi-partiality framework. There are several ways to approach the topic of neutrality in the institutional

response process. One approach involves waiting until the investigation finds whether a policy has been violated or not to determine “who to believe” (although in Title IX investigations, supportive measures should be provided to both the survivor and accused throughout the process, per federal policy). In essence, this approach may suggest that a survivor’s claim of sexual harassment may not be taken as valid until the institutional response process determines a policy has been violated. However, even if the institutional response process has concluded quickly (say, a week), harms can occur for both the survivor and accused during that window, as detailed below, and rumors may spread into the community, creating whisper networks and further offshoots of harm that may not be remediated by compliance-based supportive measures alone.

By contrast, a multi-partiality approach takes everyone at their word and seeks to be responsive to the lived experiences of all involved individuals, concurrent with the institutional response process determining the objective facts that dictate the institution’s responsibility. Under multi-partiality, if the survivor claims they have experienced sexual harassment, then individuals who may provide remediation efforts accept that claim as true up front (while the institutional response process is occurring) and can provide resources to remediate that harassment. Simultaneously, if the accused claims they have not engaged in any sexually harassing behavior but have experienced harm as a result of the accusation against them, then those claims are also accepted as true up front (while the institutional response process is occurring) and they also deserve efforts to remediate the harm stemming from the accusations against them. Accepting both claims as true up front and addressing the perceived harm, rather than waiting until the official finding of an investigation to determine “who to believe” and who the institution must legally provide support to, allows for harms to be addressed earlier and more robustly, even if the institutional response process eventually determines that behavior rising to the level of a policy violation has not occurred. Further, if individuals who are typically outside of the institutional response process (such as the broader institutional community) claim that harm has occurred as a result of the harassing behavior, then those claims of harm are also accepted up front and they also deserve efforts to remediate that harm. This multi-partiality approach focuses on the harms occurring and seeks to address them—some of which may eventually be validated as reaching the level of a policy violation and constituting sexual harassment (in turn requiring mandated remedial measures), and some of which the institution may want to address even without that validation/requirement. In this way, employing a multi-partiality framework provides the opportunity to redress the involved individuals’ experiences subjectively throughout the institutional response process, takes steps to remediate and facilitate access and participation, and allows involved individuals to proceed with what is objectively required in the investigation.

Employing a multi-partiality framework is also complementary to recognizing the range of harms experienced and the range of remediation efforts available to appropriately address that specific harm. For example, one survivor may feel that a one-time, demeaning comment about women made by a classmate caused a level of harm that can be fully remediated by speaking with a counselor at their institution (a comment that likely would not meet the reasonably high standard to constitute sexual harassment under Title IX, and that may not reach the threshold for a formal investigation). A different survivor may feel that being sexually assaulted by a community member caused a level of harm that cannot be fully remediated by counseling alone but that instead may be more appropriately remediated by employing additional efforts such as no-contact orders

(NCOs) or shuttle diplomacy. Such examples reveal how institutions can go beyond compliance and reduce harm overall (rather than just addressing the harms that rise to the level of a policy violation) by using a multi-partiality framework. We invite readers to adopt this multi-partiality approach to remediation and employ it as an underlying framework for our examination of what remediation efforts are needed and available in higher education.

Finally, we want to define the scope of this paper regarding the range of ways an institution can be informed about individual cases of sexual harassment. This paper focuses solely on instances when an institution has received formal notification that an individual has experienced sexual harassment, which we will refer to as reporting to the institution (see Box 1 for more information). A survivor may also choose not to tell anyone about the harassment or may choose to tell someone who, according to their institution’s policy, is not required to share the report with the institution (i.e., a confidential resource such as an organizational ombuds; see IOA, 2023, for exceptions to confidentiality). We chose to focus solely on disclosures and reports that involve the institutional response process as described in the definitions provided above (see Box 2). However, we want to acknowledge that the effects of sexual harassment can extend beyond what occurs before, during, and after the institutional response process, as many individuals choose to never informally disclose or formally report the harassment.3

Harms to the Survivor

The harms that survivors experience as a result of sexual harassment are well documented in research. For example, the National Academies’ 2018 report on sexual harassment summarized 30 years of research on the harms survivors often experience to their professional and personal well-being (see Chapter 4). For survivors employed in higher education, sexual harassment can result in increased work absenteeism, intent and desire to resign, decreased job satisfaction, decreased work performance and productivity, and missed work opportunities (e.g., Barling et al., 1996; Holland and Cortina, 2016). Survivors who are students also tend to have lower grade point averages; are less motivated to regularly attend their courses; are more likely to change classes, advisors, and majors; and are more likely to drop out of school overall, negatively affecting their professional trajectories (e.g., Huerta et al., 2006). Significantly, survivors also experience a host of negative personal outcomes as a result of sexual harassment. Individuals who report experiencing higher levels of sexual harassment also report experiencing elevated levels of depression, anxiety, and symptoms of PTSD, as well as disordered eating, sleep problems, respiratory distress, substance abuse, decreased self-esteem, increased self-blame, and an increased sense of stigmatization (e.g., Ho et al., 2012). Stress resulting from damage to a survivor’s educational progress

__________________

3 Individuals who have experienced sexual harassment in a higher education context often never informally disclose or formally report those experiences to others (NASEM, 2018). As the annual reports of many Title IX offices reflect, only about 25 percent of sexual misconduct reports result in formal reports, and of those that do, a majority of cases will not progress through a complete investigation, hearing, and sanctioning decision (e.g., Richards et al., 2021). The reasons for this are many, ranging from survivors’ withdrawal/desire not to pursue an investigation but rather to just receive supportive measures, insufficient evidence, the accused individual leaving the institution, the individual not being within the institution’s jurisdiction (such as someone who belongs to another institution) and pressure from countercomplaints, to changing standards within an institution for what constitutes a policy violation. Importantly, many survivors find and/or hear from others that the institutional response process itself can be traumatic and decide not to report sexual harassment to the institution because of the possibility for further traumatization (Holland et al., 2019). The result is that a very small number of institutional response processes begin and even reach the end of an investigation process. As the Remediation Working Group’s focus was on how institutions can remediate harms of sexual harassment that are eventually disclosed and reported, this paper does not speak to remediation efforts that may address harms from an incident of sexual harassment that is never shared. However, several of the identified efforts may still be useful (e.g., anonymous chat services; educational materials and trainings), and we hope that survivors who choose not to disclose or report their experience will also benefit from the efforts that institutions implement to remediate the harms of sexual harassment more broadly.

or professional career can compound the stress of the damage to their personal outcomes, and vice versa, creating a feedback loop of post-harassment harm that necessitates remediation.

Each of these negative effects may be experienced by the survivor before they report the sexual harassment to the institution (and many survivors choose never to report to the institution; see Footnote 4 above), during the institutional response process, and after the institutional response process has determined whether a policy prohibiting sexual harassment has been violated. For example, poor reactions from individuals to whom survivors initially disclose can make them hesitant to make a formal report or initiate an investigation process, fearing that officials might also cast doubt on their experience of sexual harassment and exacerbate the damage to their professional, mental, and physical well-being (Smith and Freyd, 2014). During the institutional response process (which may lead to their engagement with legal, medical, and judicial systems if those services are sought out), survivors may experience victim blaming, minimization or even dismissal of their claims, and further traumatization (Griffin et al., 2022; SAMHSA, 2014). Being subjected to medical practitioners and legal staff who are not trained to conduct their work in trauma-informed ways can retraumatize the survivor. For example, survivors’ trauma can be exacerbated during cross-examination in hearing processes (Elsesser, 2020), or in cases of sexual violence where survivors may experience medical procedures such as pelvic exams (Farid, 2019).

Survivors can also experience negative professional outcomes due to conflicts of interest and/or the stress of navigating the institutional response process, such as retaliation for reporting a professor for sexual harassment (Boyd et al., 2023) or a desire to drop classes or abstain from work activities to avoid interacting with the individual they accused (Feldblum and Lipnic, 2016). Students, employees, and non-tenured or junior faculty whose professional standing is significantly affected by faculty with the authority to evaluate their school or job performance are more vulnerable and may fear or experience retaliation in the form of formal and informal negative appraisals (Boyd et al., 2023). The survivor may also experience feelings of being betrayed by their university—termed institutional betrayal (Smith and Freyd, 2014)—in how it is conducting the investigation process and perceive that their institution is failing to live up to its stated values—that is, to thoroughly investigate harms the survivor experienced, to support the survivor, and to pursue justice on behalf of the survivor. These perceptions can be tied to decreased trust in an institution and exacerbate the harm caused by the inciting trauma (Bergman et al., 2002; Hart, 2019; Smith and Freyd, 2014).

Even after the institutional response process has concluded, survivors may continue to experience worsened mental and physical health due to post-traumatic stress, the accused still being in the community, and the stigma of being labeled a “troublemaker” in their discipline, which can result in their leaving the field altogether (NASEM, 2018). At this stage too, the survivor may experience feelings of institutional betrayal. For example, when an institutional response process concludes that the accused did not violate any institutional policies prohibiting sexual harassment, and therefore they will not be subject to any discipline, survivors may experience this outcome as a form of institutional betrayal. Lastly, the survivor may experience difficulty reintegrating into the broader institutional community. Accusing a community member of sexual harassment and having that harassment and/or accusation openly known (through gossip or whisper networks, for example) can be a stigmatizing experience, reflecting complexity around the issues of transparency and communications. The survivor may also be wary of rejoining a community where they experienced harm, particularly if they feel that the community allowed one of its members to sexually harass them, the institution failed to support them,

and/or it appeared to condone the behavior by not holding the accused individual accountable, at least from the survivor’s perspective.

Harms to the Accused Individual

We do not equate the harm that survivors of sexual harassment experience with that of others affected by the incident. However, given the attention paid to survivors’ experiences, and employing our multi-partiality framework, we note that harms can occur to the accused individual as well as to the broader community’s sense of safety and justice, necessitating resources that are specific to the various affected groups (Koss et al., 2014; Williamsen and Wessel, 2023). For example, accused individuals and bystanders to the sexual harassment may experience moral injury, defined as “severe psychological distress and functional impairments that may occur after experiencing, witnessing, perpetrating, or failing to prevent stressful events that transgress core values and moral beliefs” (Lathan et al., 2023, pp. 5136-5137; note that under this definition, survivors would also experience moral injury after experiencing a stressful event such as sexual harassment). A driver who causes a car accident and hurts another driver (even unintentionally) may feel moral injury because this contradicts their view of themself as a safe and considerate person. Similarly, individuals accused of sexual harassment may feel moral injury because being accused of engaging in sexually harassing behavior violates their view of themselves as benevolent people. Research shows that experiencing moral injury can be related to dysfunction in the injured party’s parasympathetic nervous system (e.g., cardiovascular disorders) (Lathan et al., 2023) and severe anger, depression, and PTSD symptoms in some circumstances (Hoffman et al., 2018).

Indeed, the limited research on the effects of sexual harassment on accused individuals, in combination with media coverage, interviews, and research on organizational climate, suggests that harm for these individuals can occur before, during, and after the institutional response process. In addition to moral injury, it is possible that the accused individual may feel angry, confused, ashamed, surprised, and/or scared about what the survivor is claiming and how it could affect their future (Penn State Student Affiars, n.d.; Stanford University, n.d.; Washington University in St. Louis, n.d.). For example, if the survivor tells others in their shared network, those individuals may ostracize the accused (LCW, 2024). If the accusation is leaked on social media, the accused individual may experience online bullying or doxing (in which an individual’s private information, such as their residential address, is shared publicly to promote harassment or violence toward them; NYCLU, 2024). They may also experience general “cancellation” or “calling out” (which involves “public criticism and withdrawal of support for those who are assessed to have said or done something problematic, which could easily progress into online harassment”; Kim et al., 2022). During the institutional response process, the accused individual may experience harms through the same mechanisms as the survivor, as investigative processes that are not trauma-informed can be invasive and stressful (Koss et al., 2014; Smith and Freyd, 2014). The accused individual may be subjected to repeated inquiries into the details of their personal life and like the survivor may also experience institutional betrayal if they perceive the institution has taken or failed to take action on their behalf. Moreover, just as they may fear becoming the target of personal and professional retaliation, as described above, they can also be accused of retaliating against whoever reported them for sexual harassment, including the survivor, particularly if they hold a position of authority (such as a work supervisor or instructor).

Finally, after the institutional response process has concluded, the accused individual may experience difficulty reintegrating into the community (such as returning from a leave of absence taken while an investigation was being conducted). For example, the accused individual may have difficulty making social connections, finding employment, or participating in community social events (Grossi, 2017). The stigma of being accused may also be compounded if the investigation concludes that the individual did violate a policy prohibiting harassment (Karp and Frank, 2016). This process can be further complicated if the survivor reintegrates into the same spaces as the accused, requiring that the two individuals navigate how they will interact (or not interact) with one another moving forward.

Harms to the Broader Institutional Community

Individual cases as well as more comprehensive research of sexual harassment reveal that members of the broader community also experience harm. Witnesses of sexual harassment who are employees of an institution experience similar levels of job dissatisfaction, work absenteeism, psychological distress, and desire to resign as individuals who directly experienced sexual harassment (NASEM, 2018). As mentioned in the prior section, they might also experience facets of moral injury, particularly if they were bystanders to the incident and perceive themselves as “failing to prevent stressful events that transgress core values and moral beliefs” (Lathan et al., 2023, pp. 5136-5137). Members of the community are also affected when their sense of safety is compromised or when they lose trust in the fairness of the system that is supposed to prevent harm and address it if it has happened (Nix et al., 2015; Umphress and Thomas, 2022). Overhearing that someone has experienced an organizational process as procedurally unjust (i.e., one in which the process is perceived to be unfair to an involved individual or group) is associated with willingness to retaliate against the person responsible for the injustice (in this context, the institution; Skarlicki and Kulik, 2005).

Part of what informs perceptions of an institution’s procedural justice is its level of transparency, which can be very difficult to balance with protections and restrictions around privacy. As stated previously, members of the broader community may observe apparent harassing behavior before anything is disclosed to the institution and interpret the absence of a public acknowledgment of the incident as a lack of response on the part of leadership and the institution (Fink, 2023; Harvard University, 2021), which might increase students’, employees’, and other community members’ feelings of being in an unsupportive climate or environment. Even after the harassment is disclosed, privacy laws (such as FERPA, HIPAA, and FMLA) and risk mitigation approaches may keep the institution from sharing updates and information with the community members on how it is responding, which may make community members feel uninformed and distrustful even if the institution is in fact responding in an appropriate manner. In line with this, community members may also experience organizational cynicism, or “an attitude of pessimism and hopelessness towards future organizational change induced by repeated exposure to mismanaged change attempts” (Andersson and Bateman, 1997, p.450), which has been tied to employee resistance to organizational change and decreased trust in an organization (as described in Cheung et al., 2018).

Finally, as individuals accused of sexual harassment are reintegrated into the community, the members of this community may experience a decreased sense of safety and increased sense of injustice and betrayal by the institution (McMahon et al., 2019). For example, in a highly publicized series of cases, a well-known biologist

was found responsible for sexual harassment at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and was then offered a position in New York University’s (NYU’s) medical school. Faculty, students, and postdoctoral scholars across NYU protested this potential employment, citing fear for their trainees’ and their own safety, describing an impending sense of betrayal if the institution followed through with the offer, and suggesting that they would boycott events by the medical institute if NYU continued to pursue the biologist’s employment there (Wadman, 2022). Eventually, both NYU and the biologist dropped the offer, but in November 2023 the biologist was offered a position at the Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry (IOCB) Prague amidst concerns that hiring the biologist would send a message to “all women and men in Czech academia” that sexually harassing behavior is tolerated (Wadman, 2023). As the discussions about this individual’s termination and employment reflect, broader institutional communities can be deeply affected by sexual harassment–related harm that occurs not just at their own institution but across institutions globally.

Factors that Might Cause Additional Harms to Survivors, Accused Individuals, and Community Members

Beyond the three roles of survivor, accused individual, and community member, there are certain factors that might cause additional risk of experiencing sexual harassment, or harm resulting from the institutional response process. People with certain demographic identities, those who are subject to power differences/hierarchies, and individuals who hold a professional role in the institutional response process all are more likely to experience sexual harassment or institutional response process-related harm. When an individual holds multiple of these additional risk factors, the resulting harms can intersect to simultaneously compound the damage and marginalize their experiences. Given this, it is important to consider how remediation efforts may need to be tailored to fully address the harms created by these additional factors. In this final section, we examine how individual context and identity relate to (1) the likelihood of experiencing additional harm and (2) the importance of considering these factors in remediation efforts in higher education.

Research demonstrates that some individuals are more likely to experience sexual harassment or harm resulting from participating in the institutional response process based on their demographic identities, their professional roles at their institution, and/or the hierarchical power dynamics of the contexts in which they work and study. For example, women are more likely to experience sexual harassment than men, and transgender individuals and non-heterosexual (e.g., lesbian and gay) individuals are more likely to experience sexual harassment than cisgender and heterosexual individuals, respectively (NASEM, 2018). Similarly, power differentials and the hierarchical systems for graduate training, hiring, and tenure and promotion in higher education can also make certain individuals more vulnerable to sexual harassment and can compound the harm.4 Power differentials occur when one person (or group) has “more or less influence or control over a situation and valued resources based on their position, title, gender, race, level of authority, etc.” (Umphress and Thomas, 2022). Power differentials may come into play under various circumstances, such as between advisors and advisees, individuals overseeing visa processes for non-U.S. citizen students or employees, or those later in their career mentoring individuals earlier in their career. In these cases, the individual with less power (the advisee, non-U.S. citizen, and early career scholar) can face an elevated risk of harassment and fear of retaliation from

__________________

4 As discussed at length in the paper “Preventing Sexual Harassment and Reducing Harm by Addressing Abuses of Power in Higher Education Institutions” (Kleinman and Thomas, 2023).

the individual with more power (the advisor, U.S. citizen, and later-career scholar) (Kleinman and Thomas, 2023). For example, an individual who is not a U.S. citizen may be afraid to report their advisor (a U.S. citizen) for sexual harassment if they fear the advisor could take action that results in their visa being rescinded. Similarly, an early-career individual (e.g., a postdoctoral scholar) may be at greater risk of experiencing sexual harassment from a late-career individual (e.g., a tenured faculty member) and also more hesitant to report the harassment because they rely upon the senior colleague for letters of support to acquire a full-time position or professional awards. Furthermore, even those individuals holding positions of power remain vulnerable to experiencing sexual harassment from individuals with less positional power, also known as contrapower harassment (Viveiros et al., 2024).

Finally, some individuals occupy specific roles that increase their likelihood of experiencing harm due to their responsibility for facilitating the institutional response process. For example, some members of the community have roles in the institutional response process where they are expected to respond to disclosures of sexual harassment. This could include faculty and staff with responsible employee or mandatory reporter status, directors of undergraduate and graduate studies, and department heads, deans, and other administrators. Because of their roles, these individuals may struggle with burnout, frustration, compassion fatigue, and secondary traumatization stress (defined as the stress that results from hearing directly from someone about their traumatic experience and helping that individual learn about and navigate institutional resources) (Figley, 2002; Miller, 2018).