State DOT Policies and Practices on the Use of Corrosion-Resistant Reinforcing Bars (2025)

Chapter: 3 State of Practice

CHAPTER 3

State of Practice

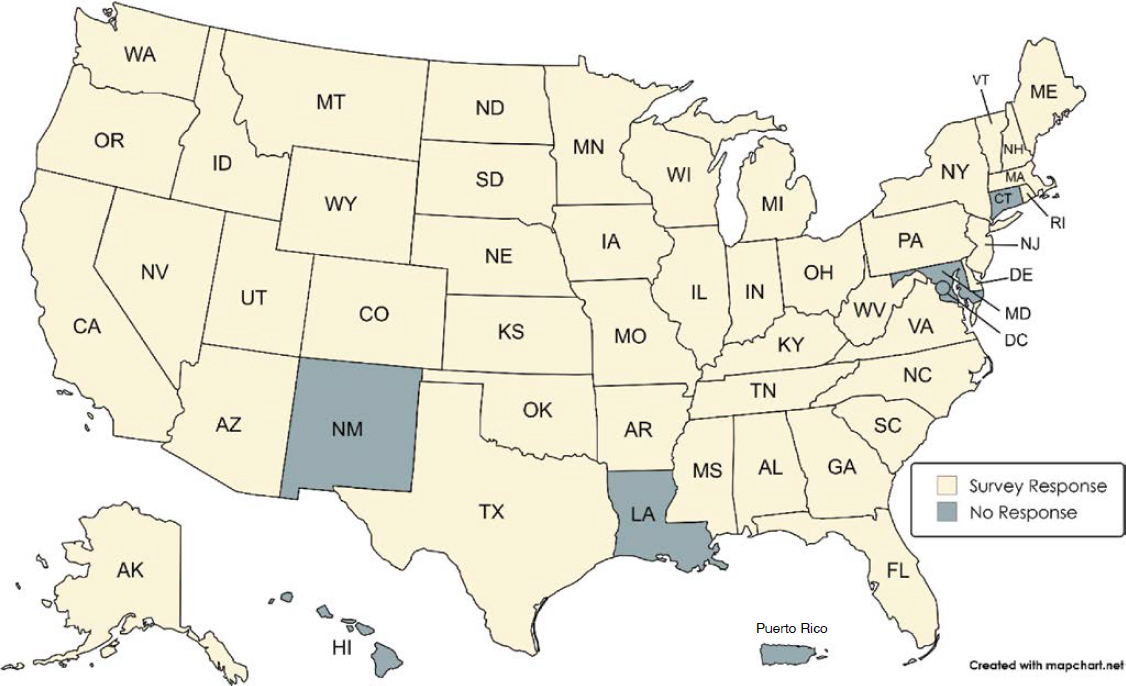

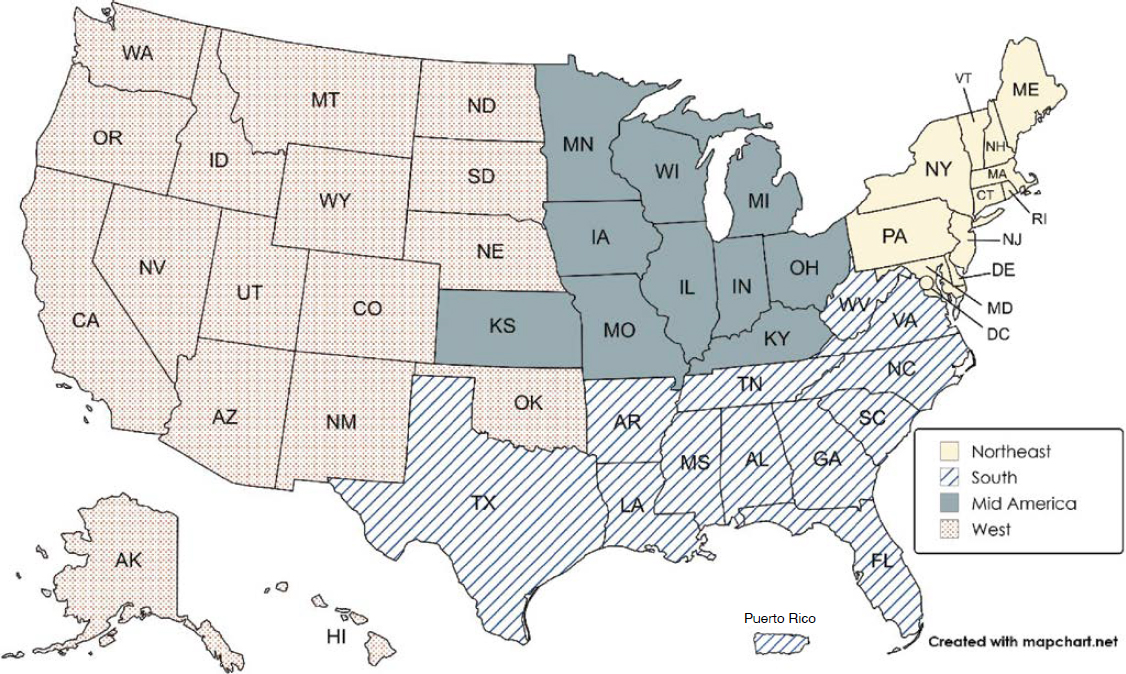

A survey on state policies and practices regarding CRRBs was distributed to 52 voting members of the AASHTO Committee on Bridges and Structures (representing each state, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia). This chapter summarizes these results along the themes of frequency of use, decision-making processes, design and construction considerations, limitations and challenges, benefits, implementation, and other considerations. Throughout this discussion, graphs are presented that generally indicate the number of state DOTs providing a certain response, in order to provide clarity on the scale on the responses. To provide context for these numbers, discussion of these figures generally focuses on the percentage of respondents.

Additional information on the survey is provided in Appendices A through D. The survey is provided in Appendix A. Responses were received from the 45 state DOTs listed in Appendix B and illustrated in Figure 3-1. The responses given by each state DOT are detailed in Appendix C. It is noted that some survey questions allowed the option to choose “other” and enter custom text as a response; when this option was selected, the specific responses are given in Appendix C. The survey also requested that state DOTs provide links to their relevant documentation related to CRRB. These responses are tabulated in Table C-51 in Appendix C.

Frequency of Use

This section provides an overview on the frequency of use of the various options for reinforcing bars. The results are organized by time period, by member type, and by geography in three subsections. The frequency of use of the specific options within the CRRB categories that contain multiple variations (i.e., galvanizing, stainless steel, and FRP) is then described.

Past, Present, and Possible Future Use

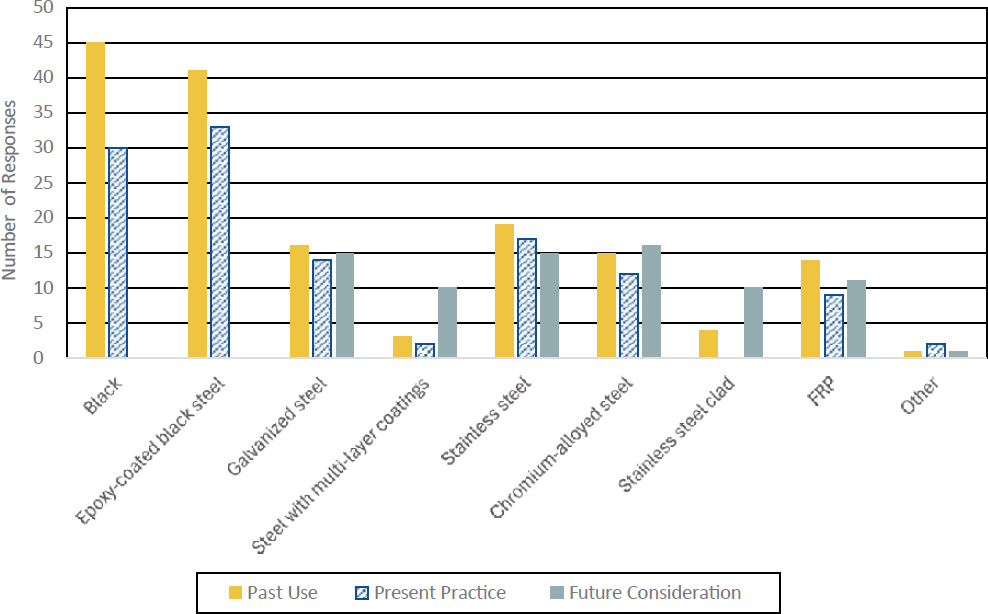

Figure 3-2 shows the number of respondents that typically use each type of reinforcing bar in past or present practice. It is noted that—in this and in all subsequent figure captions associated with survey response data—the number of responses being considered (e.g., n = 45) is indicated for clarity. In addition, the survey asked if there were bar types not presently used by the state DOTs that they were considering using. This data is also reported in Figure 3-2.

The data in Figure 3-2 shows that all respondents have used black bars at some point, but this has decreased to 67% of the respondents presently using this bar type. The use of epoxy-coated bars is slightly more widespread than the use of black bars at present (73% of respondents). At the present time, stainless, galvanized, chromium-alloyed, and FRP bars are the next most widely used bar types (at 38%, 31%, 27%, and 20% of respondents, respectively). Steel with multilayer coatings and other bar types not directly included in the survey are rarely used at present (7% and 4% of respondents,

respectively). Textured epoxy-coated and epoxy-coated A1035 were listed as the other bar types typically used. No state DOTs reported presently using stainless steel clad reinforcing bars.

In considering the aggregated past and present use, all respondents have experience with black bars and nearly all (42 of 45, or 93%) have experience with epoxy-coated bars. One state DOT clearly indicated that it does not use or plan to use this bar type; two other state DOTs did not provide an answer regarding their use of epoxy-coated bars. The majority of respondents (24 of 45, or 53%) have also used stainless steel bars. Galvanized steel, chromium-alloyed steel, and FRP have been used in similar proportions (by 38%, 38%, and 33% of respondents, respectively). Fewer than 10% of respondents have used steel with multilayer coatings, stainless steel clad, or other reinforcing bars.

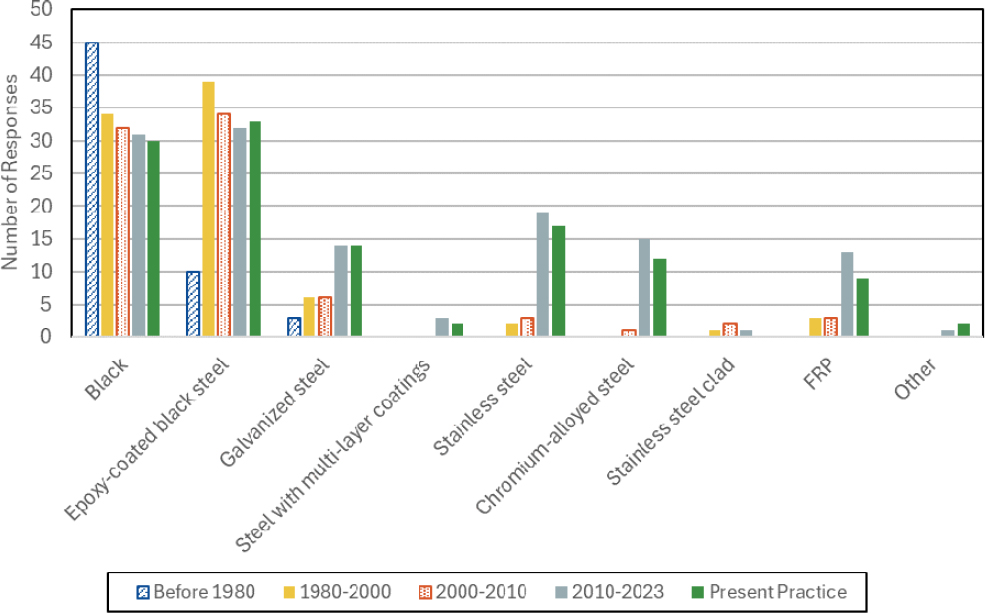

Figure 3-3 provides more refined data on the historical and present use of different reinforcing bar types. It shows that although black bars were the most popular reinforcing bar type prior to 1980, epoxy-coated bars have been the most popular type in every time period considered since then. However, the use of epoxy-coated bars has decreased since 2000, with all other CRRB options except stainless steel clad becoming more widely used over the same time period.

The data discussed in this section is based on inquiries regarding the respondents’ typical practice. This is in contrast to the more detailed analysis of some material types that follow in the Specific Material Types section, where the focus is any use of given materials, including experimental use in demonstration and pilot projects.

Consequently, it is logical that the number of respondents indicating the use of certain bar types in the Specific Material Types section is larger than what is discussed in this present section.

Use by Member Type

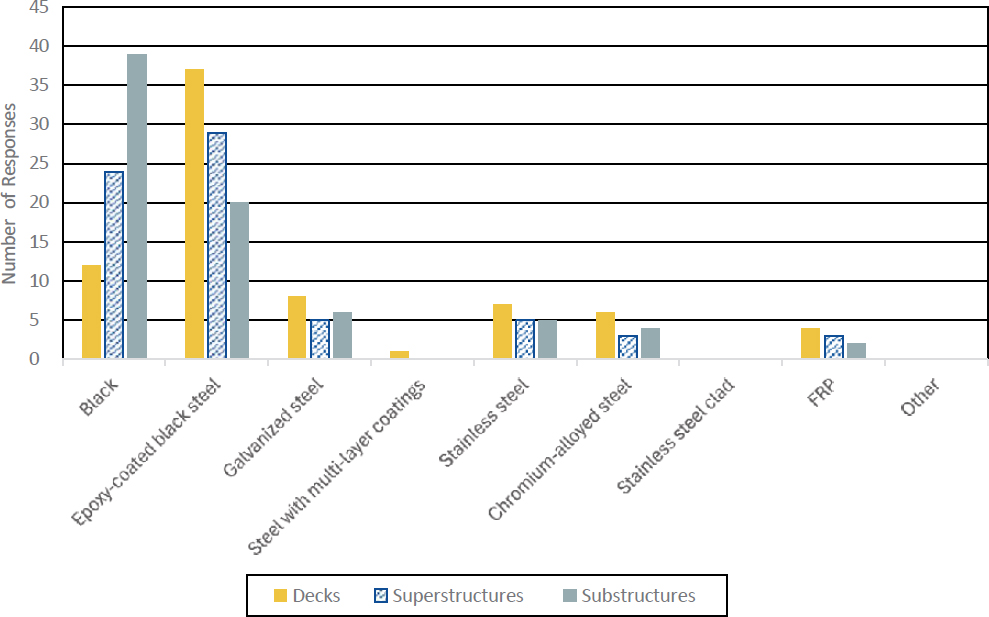

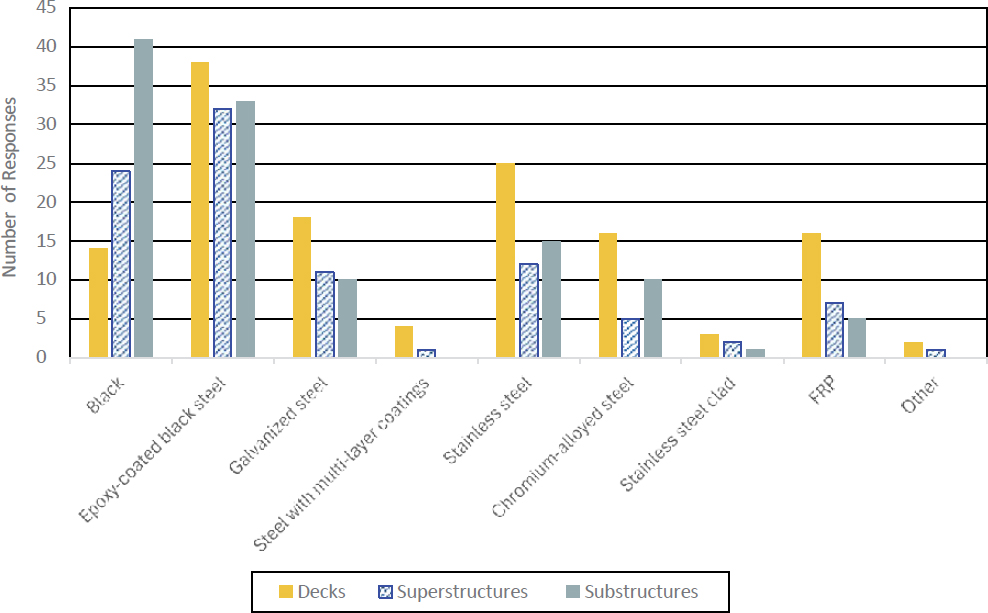

In addition to the general information on bar types used that was described in the previous section, state DOTs were asked to separately consider the use of each reinforcing bar type in decks, superstructure members, and substructure members. Frequency of typical use in each of

these situations was also queried with four options: (1) not typically used; (2) sometimes used but not a standard option; (3) one of several materials commonly used; or (4) most commonly or solely used. These latter two options (3 and 4) were collectively considered to represent common use; the latter three options (2, 3, and 4) were collectively considered to represent typical use. The distinction between these two terms is that typical use is not necessarily frequent, while commonly used bar types are used frequently. These more refined queries sometimes resulted in respondents reporting typical use in response to these questions despite not indicating typical use of specific bar types in prior queries, which were summarized in the previous section.

Figure 3-4 summarizes the data on bar types that was indicated as being used commonly. This figure shows that black bars are the most widely used reinforcing bar type for substructures (87% of respondents) while epoxy-coated bars are the most widely used material in decks (82% of respondents) and superstructures (64% of respondents). These two bar types are the second most widely used for each member type for which they are not the most widely used, but the specifics of this trend vary between member types. For decks, epoxy-coated bars are commonly used by three times the number of state DOTs than any of the other options. Conversely, for substructures, black bars are used commonly by nearly twice as many respondents (87% using black bars compared to 44% using epoxy-coated bars). For superstructures, the use of these two bar types is more comparable to one another, with epoxy-coated bars being used by 64% of respondents and black bars being used by 53% of respondents.

Figure 3-4 also shows that galvanized, stainless steel, chromium-alloyed steel, and FRP bars are commonly used in similar proportions to one another. The most widespread common use of these bar types is in decks (9% to 20% of respondents). They are also generally used more often in substructures than in superstructures, likely due to the substructures being more frequently located in splash zones from either marine environments or deicing agent use from underpassing roadways. Figure 3-4 shows that one state DOT reported commonly using steel with multilayer coatings (in decks); no respondents indicated commonly using stainless steel clad bars.

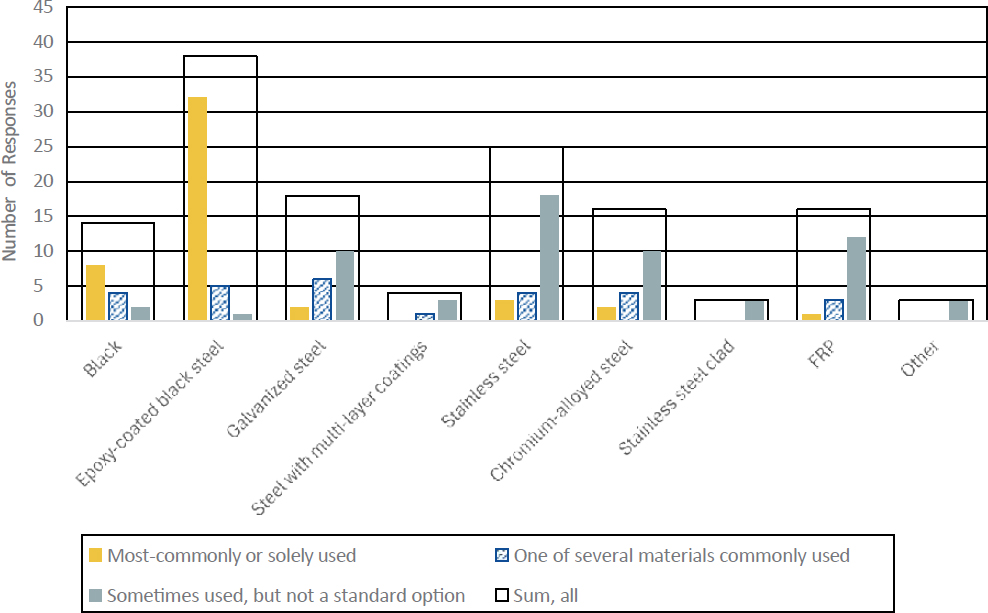

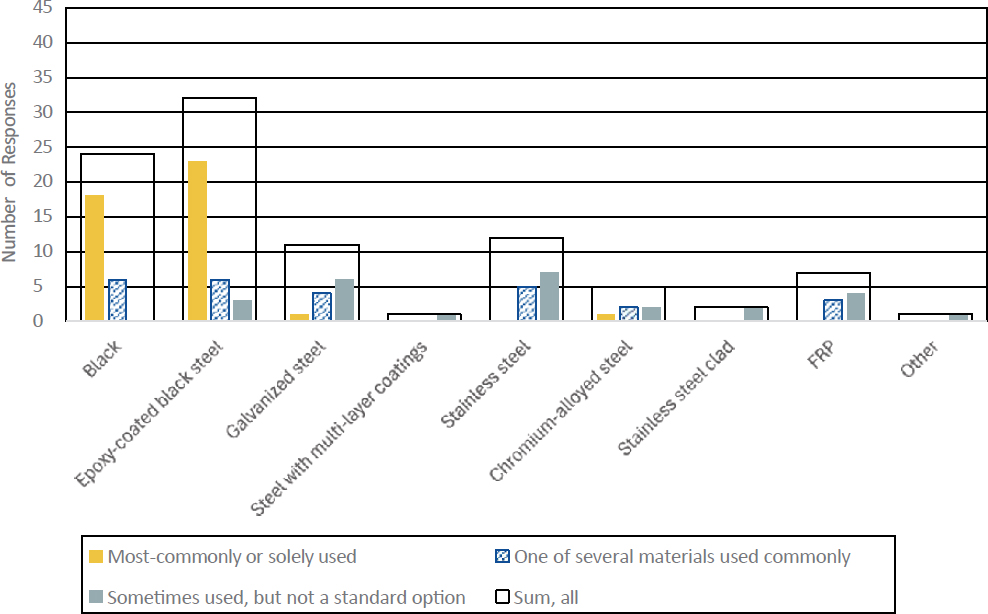

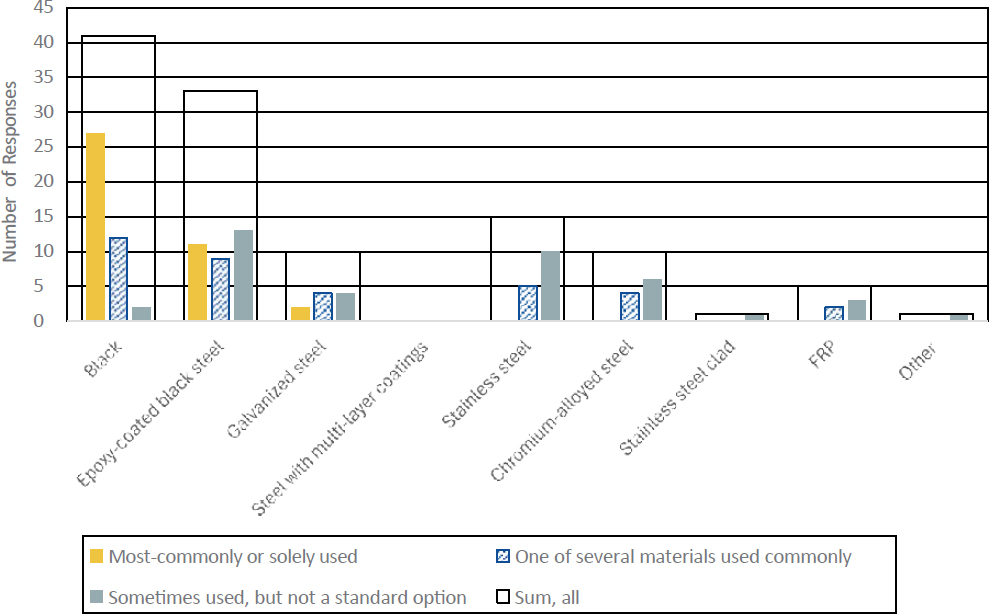

Figure 3-5 shows typical use of each bar type by member type. It represents the data that was previously shown in Figure 3-4 as well as responses that indicated that a bar type was sometimes used but was not a standard option. The trends of these two graphs are similar, but the largest increases between typical use and common use occur for epoxy-coated and stainless steel bars in substructures (an additional 29% or 22% of respondents, respectively) as well as for galvanized, stainless steel, chromium-alloyed, and FRP bars in decks (an additional 22% to 40% of respondents). When the data is viewed from this perspective, stainless steel bars are the second most widely used bar type in decks in terms of number of state DOTs that use this bar type in typical practice.

Figure 3-6, Figure 3-7, and Figure 3-8 provide a more detailed analysis of the data in Figure 3-4 and Figure 3-5 by plotting the responses to the three options on frequency of use that were given for each bar type: (1) it is the most commonly or solely used type of reinforcement bar for the given scenario; (2) it is one of several reinforcement bar types used in the given scenario; or (3) it is sometimes, but not typically, used. Figure 3-6, Figure 3-7, and Figure 3-8 also display the sum of these options in the background to represent the bar types that are used to any extent in each scenario, as shown in Figure 3-5. The sum of these first two options was classified as common use and represents the data shown in Figure 3-4. Figure 3-6 shows that, in state DOTs where epoxy-coated bars are used in decks, they are typically the most commonly or solely used reinforcing bar in these situations. The same trend is observed for black and epoxy-coated bars in superstructures in Figure 3-7 and for black bars in substructures in Figure 3-8.

Use by Geographic Region

Because the use of CRRBs is motivated by exposure to deicing agents and marine environments, it was of interest to evaluate whether there are significant differences in the reinforcing bar types presently used in different geographic regions. As a simple means of evaluating the influence

of geography, this data was considered relative to the four AASHTO regions. For the two states that are divided between different regions, these responses were solely allocated to a single region to simplify the analysis. Texas was assigned to the South dataset (to be considered among other states with bridges that are potentially affected by marine environments) and Kentucky was assigned to the Mid America dataset (to be considered among other states with bridges that are potentially affected by deicing agents). This resulted in the regional classifications shown in Figure 3-9.

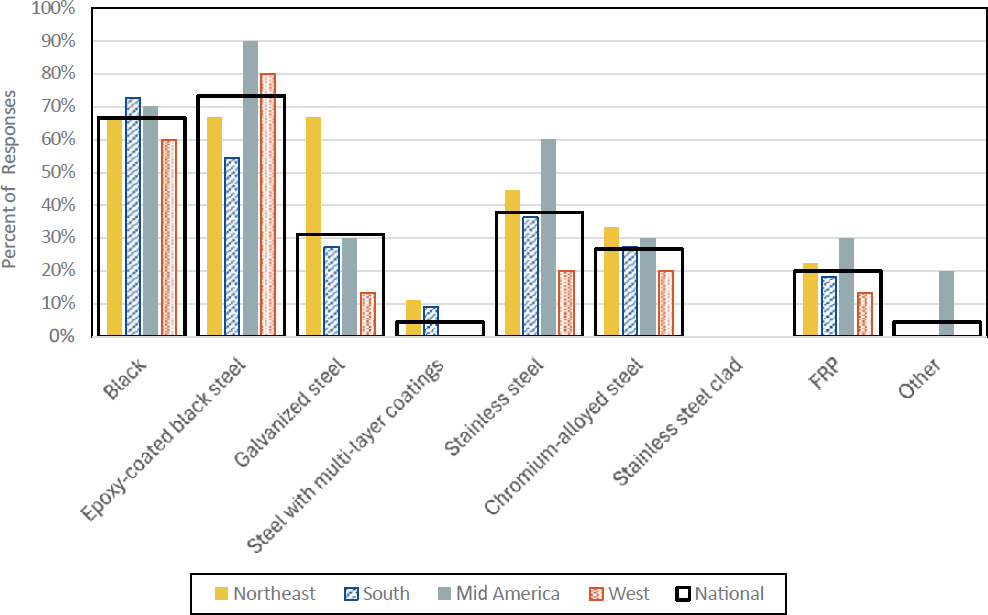

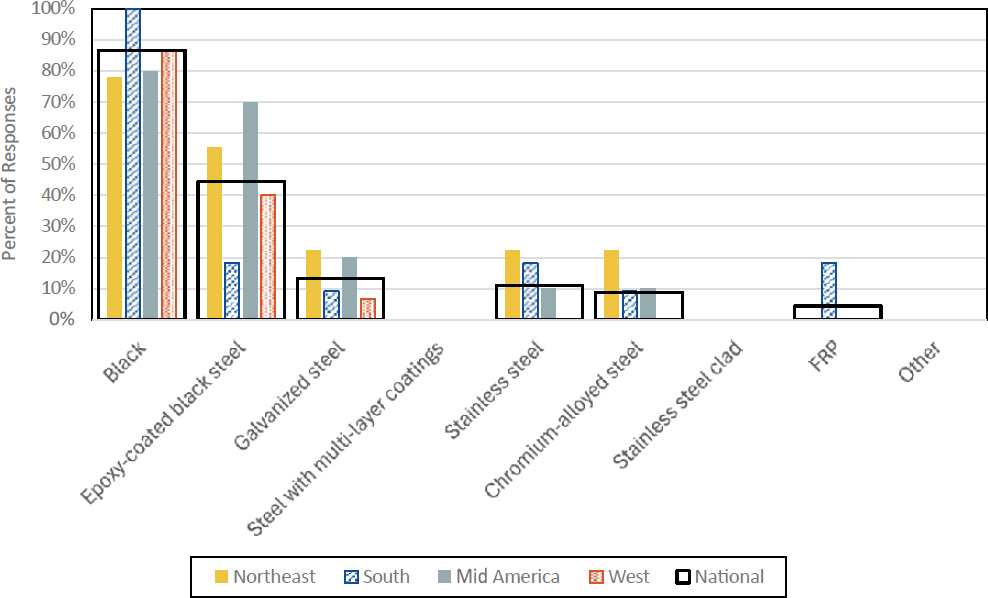

Figure 3-10 reports the presently used bar types in each of the four AASHTO regions, with the national values plotted in the background. In Figure 3-10, the vertical axis is changed to reflect the percentage of respondents in each region. This is done to normalize the results because of the different number of states and respondents in each region. Figure 3-10 shows that some bar types are used consistently throughout the United States; there are regional differences for others. For example, black, chromium-alloyed, and FRP bars are used by similar percentages of state DOTs in each of the four AASHTO regions. Of the bar types for which there are differences between regions, epoxy-coated steel is used most extensively in the Mid America and West regions. Galvanized steel is used much more extensively in the Northeast region (67% of respondents) than in other regions (where the next highest rate of use is 30% for Mid America). Other noteworthy regional variations are the significant variation in the percentage of states in each region typically using stainless steel (with the proportion of states in the Mid America region being three times that rate for the West) and that only state DOTs in the Northeast and South are indicated presently using steel with multilayer coatings.

Figure 3-10 also allows for an analysis of the most widely used bar types in each region. These are shown to be black and epoxy-coated bars for all regions. In the Northeast, galvanized bars have equally widespread use. In the other regions, following black and epoxy-coated steel, stainless steel is the bar type used by the most state DOTs (tied with chromium-alloyed in the West) and this bar type is used by a similar proportion of the Northeast state DOTs that responded to the survey.

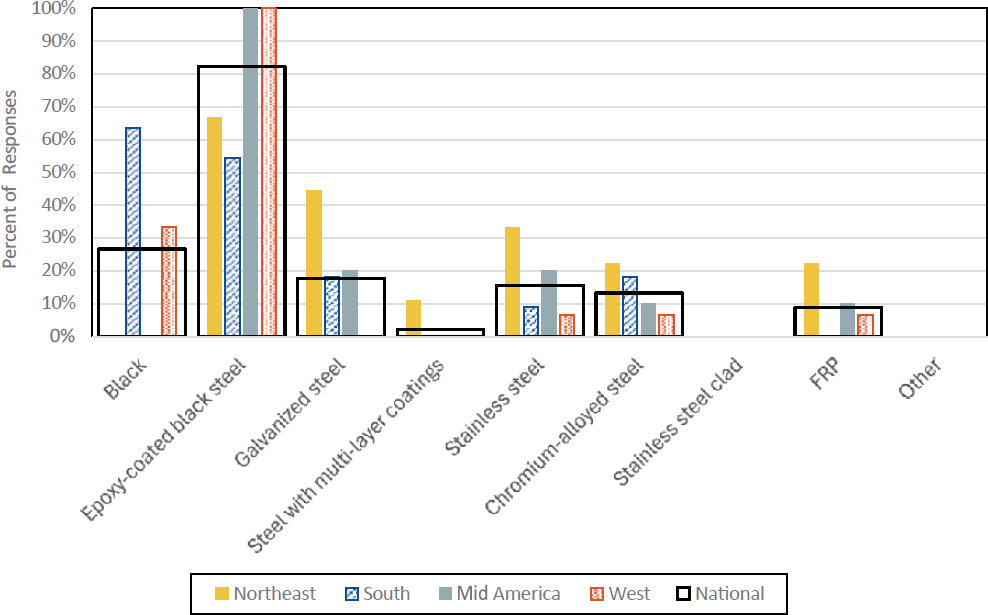

Figure 3-11, Figure 3-12, and Figure 3-13 display similar regional data showing the bar types commonly used in each member type (i.e., for decks, superstructures, and substructures, respectively). These figures represent subdivision into geographic regions of the data that previously appeared in Figure 3-4. It is also conceptually similar to dividing the data in Figure 3-10 by member type, but that data was obtained from a different survey question; consequently there are some inconsistencies in making direct comparisons between these two figures.

Figure 3-11 shows that no state DOTs in the Northeast or Mid America regions reported using black bars in bridge decks. Instead, in the Mid America region, epoxy-coated bars are used by all respondents and other bar types are used at levels generally consistent with national averages. Epoxy-coated bars are also the most common reinforcing bar type in the Northeast, but in that region the use of all other bar types (except black bars) exceeds national averages.

Figure 3-11 also shows that more state DOTs in the West use black and epoxy-coated bars in bridge decks compared to national averages; proportionately fewer of them use other bar types. The largest differences between bar use in decks in the South and in the national averages is that significantly more state DOTs use black bars and fewer use epoxy-coated bars, which is reasonable considering the limited use of deicing agents in many areas of the South region. Although chlorides from marine environments are a concern in many states in the South, most areas of these states are a sufficient distance from the coastline to be immune to these effects. The use of other bar types in the South is generally consistent with national averages.

Figure 3-12 shows some of the same regional trends for superstructures as seen for decks, such as that (proportionately) more state DOTs in the South and West use black bars, more in the Mid America region use epoxy-coated bars, and more in the Northeast use all other bar types in common use. Some notable differences between the trends in Figure 3-12 as compared to those in Figure 3-11 are (1) increasing percentages of state DOTs using black bars in all regions and (2) fewer states using each type of CRRB. This is logical, as decks are generally the members with

the greatest chloride exposure in regions where deicing agents are used. Figure 3-12 also shows that no state DOTs in the West indicated using any form of CRRB in superstructures (other than epoxy-coated reinforcing bars).

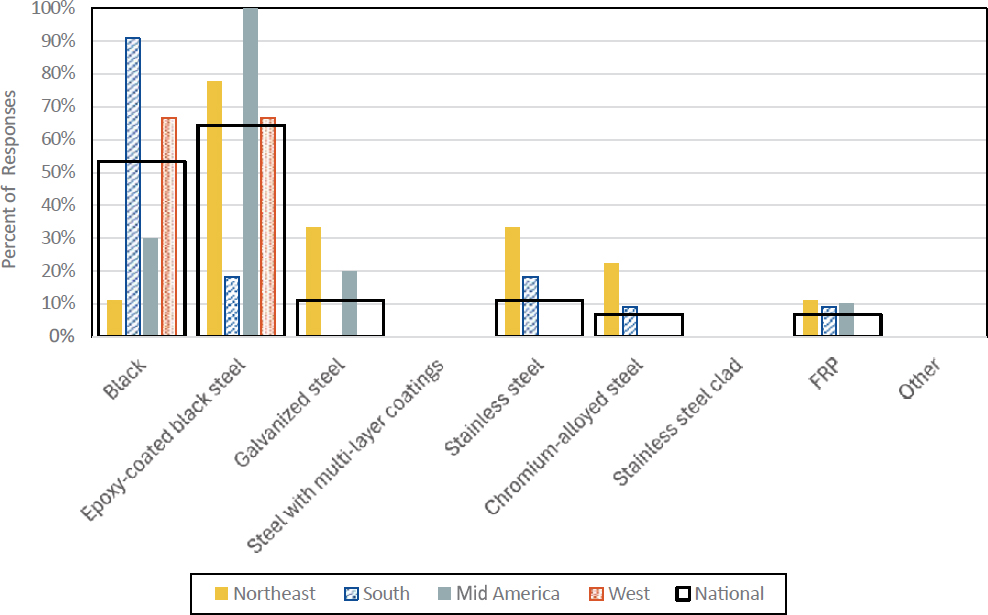

Comparing Figure 3-13 to the previous two figures shows that as the members become further from the bridge deck, there is an increased use of black bars and a decreased use of CRRBs. It is clearly recognized that the bridge deck is not the only source of chlorides and that substructures can receive the greatest exposure to chlorides from deicing agents when located in the splash zone of underpassing roadways and from marine environments. Some subtle increases in the percentage of state DOTs using some CRRBs in Figure 3-13 compared to Figure 3-12 may be the result of these types of considerations.

Finally, collectively comparing Figures 3-11, 3-12, and 3-13 to the trends in Figure 3-10 shows that while the overall use data show consistent use of black bars, the more refined data show that black bars are only consistently used nationwide in substructures. This also shows that while black, epoxy-coated, and galvanized bars were generally used by equal numbers of respondents in the Northeast, epoxy-coated steel is the most widely used for decks and superstructures and black bars are most widely used for substructures. The Northeast could also be stated to be the region with the greatest variability in approaches, as it is the only region where no combination of bar type and member type was selected by all respondents (in contrast to, for example, epoxy-coated bars in decks for the Mid America and West regions and black bars in substructures in the South).

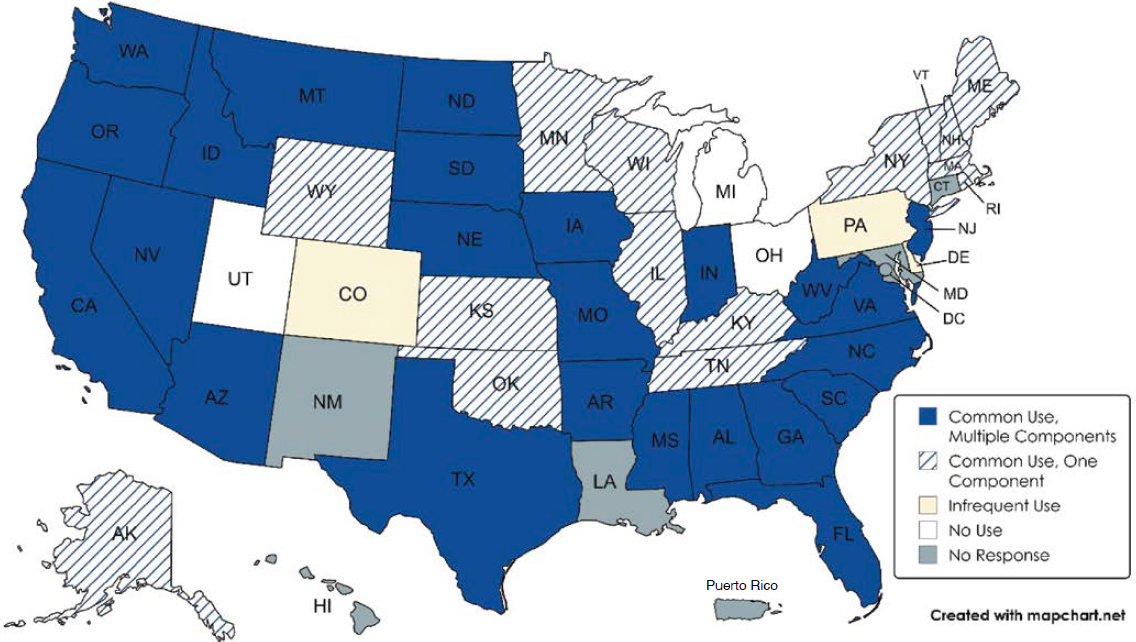

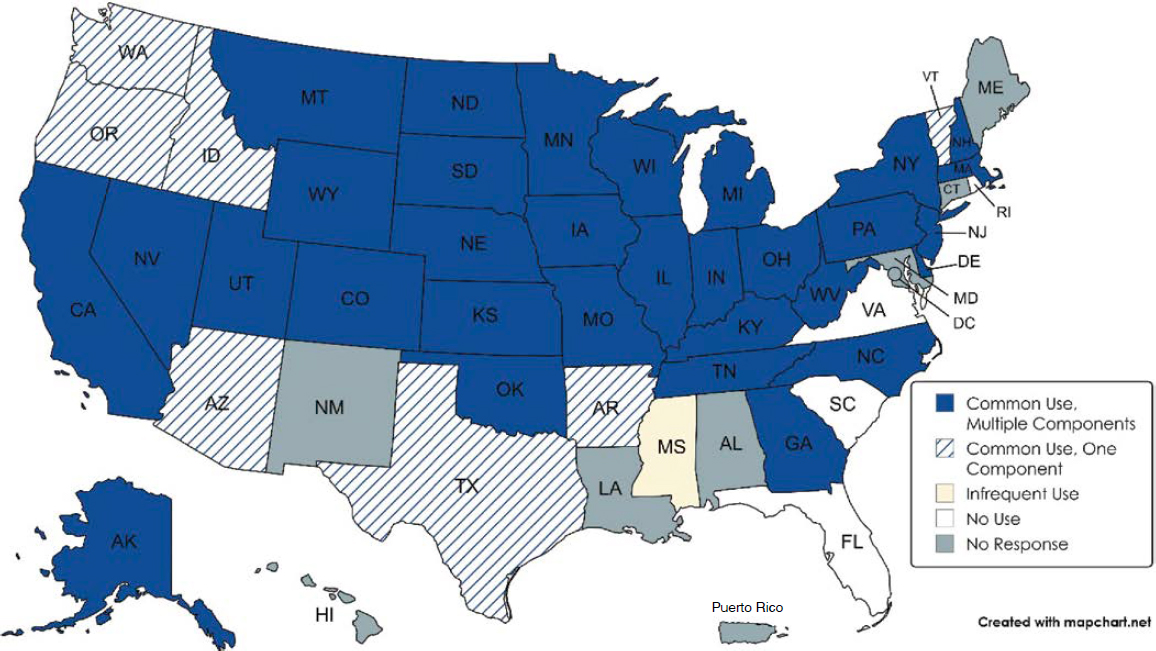

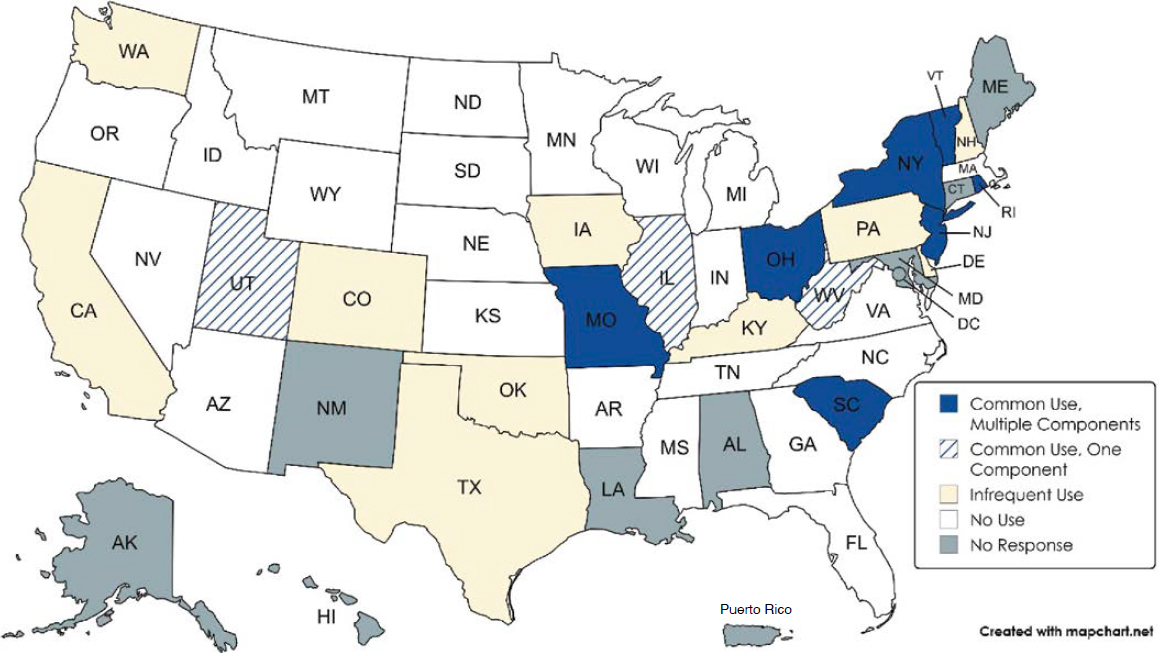

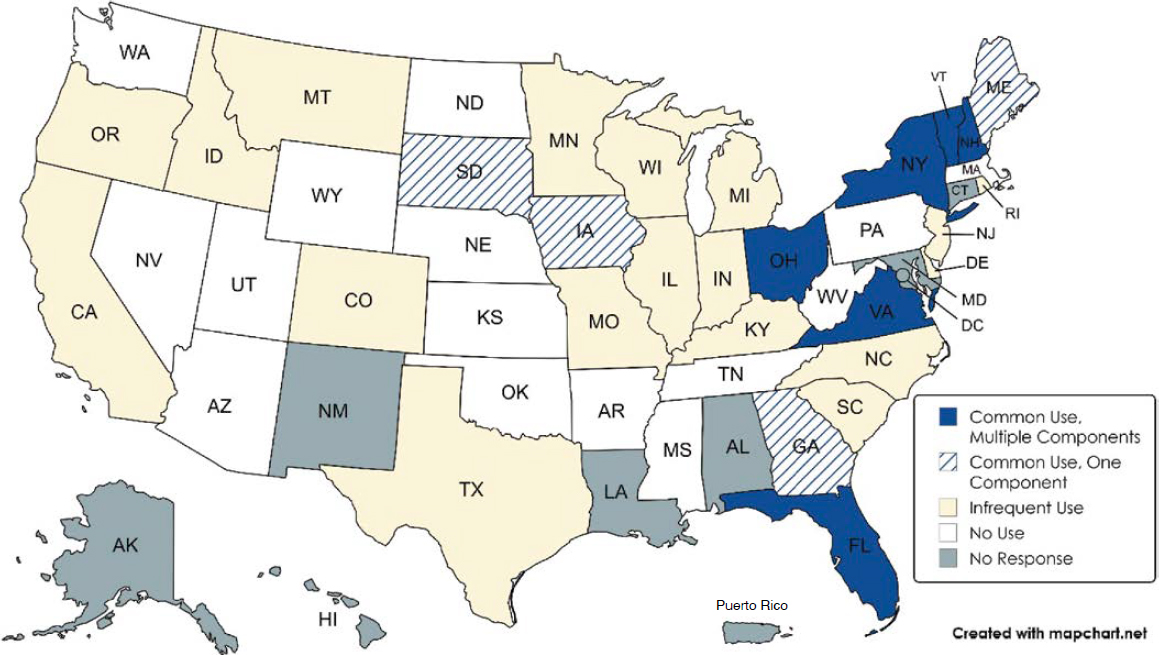

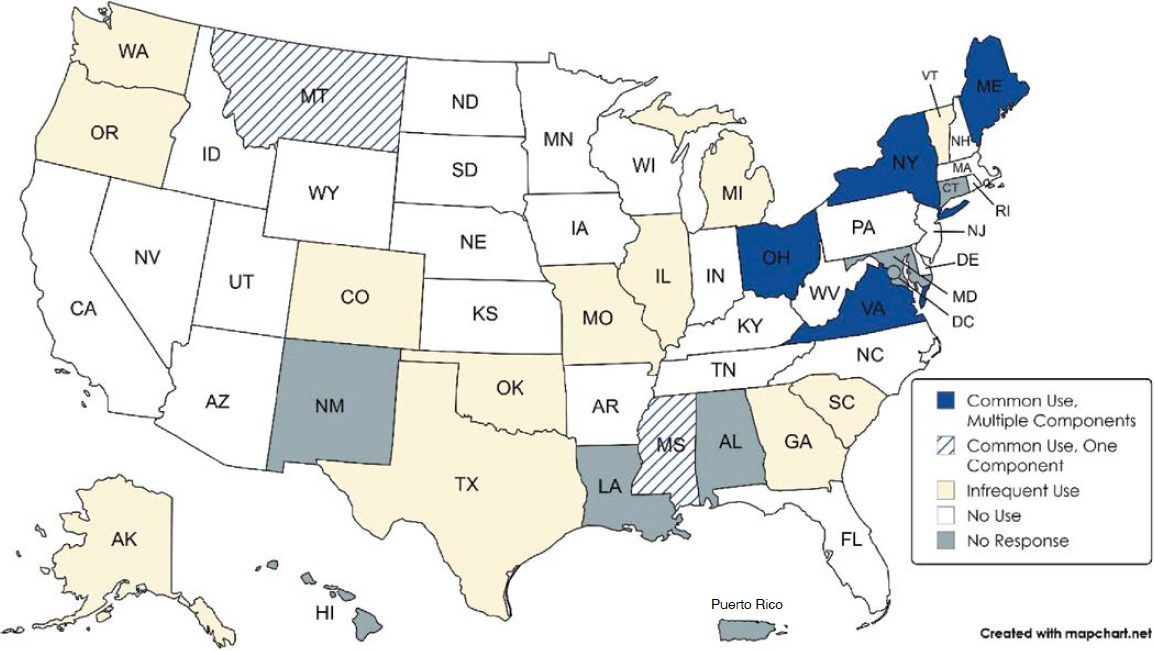

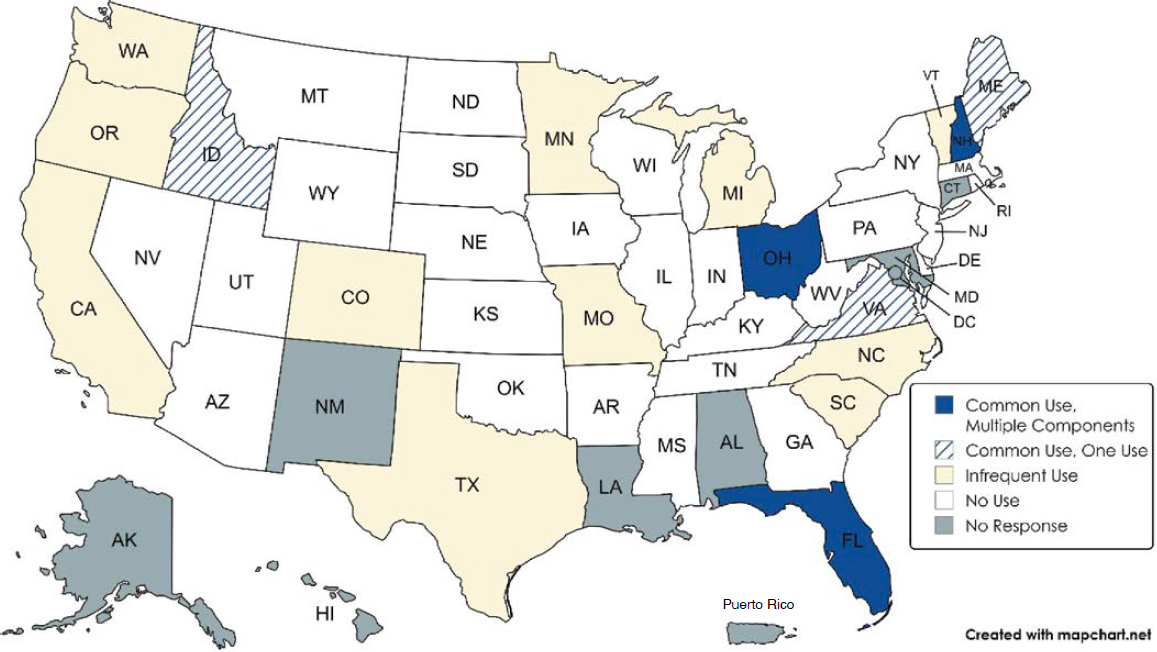

Figures 3-14 through 3-19 illustrate the specific state DOTs that presently use (in their typical practice) black, epoxy-coated, galvanized, stainless steel, chromium-alloyed, and FRP reinforcing bars. These bar types are selected because they are the most commonly used bar types based on the data in Figures 3-11, 3-12, and 3-13. Figures 3-14 through 3-19 classify the use of each bar type into one of the following categories:

- Common use, multiple components. This means that the state DOT represents one of the states that commonly use this bar type in two or all of Figure 3-11, Figure 3-12, and Figure 3-13.

- Common use, one component. This means that the state DOT represents one of the states that commonly use this bar type in only one of Figure 3-11, Figure 3-12, or Figure 3-13.

- Infrequent use. This means that the state DOT indicated that the CRRB type was used as part of typical present practice but not commonly.

- No use. This means that the state DOT indicated that it does not use this CRRB type in decks, superstructures, or substructures.

- No response. This category includes state DOTs that did not respond to the survey and those that did not choose any of the available options regarding frequency of use for that bar type.

Figures 3-14 through 3-19 reinforce the main ideas previously discussed. For example, figures 3-14 and 3-15 compared to figures 3-16 through 3-19 illustrate that black and epoxy-coated bars are the types most widely used nationally. However, the use of black bars is more limited in the Northeast, northern Mid America, and in some of the more mountainous states in the West (where there may be greater effects of the use of deicing agents) while the use of epoxy-coated bars is more limited in the southern states (perhaps due to limited need for CRRBs, as this trend also appears in figures 3-16 through 3-19).

Figure 3-16 illustrates that the most widespread use of galvanized bars is in the Northeast. The typical present use map shown in Figure 3-17 again demonstrates that stainless steel reinforcing bars are the most widely used CRRB type after black and epoxy-coated reinforcing bars, but they are not used commonly. Figure 3-18 shows that the use of chromium-alloyed bars is

approximately evenly distributed geographically, but common use of this material for multiple bridge components is concentrated in the Northeast and nearby states. Figure 3-19 shows that the use of FRP reinforcing bars is also approximately evenly distributed geographically. Refer to the survey results of questions 2 through 4, which are documented in Appendix C (tables C-17 through C-19) for additional information on specific state responses.

Specific Material Types

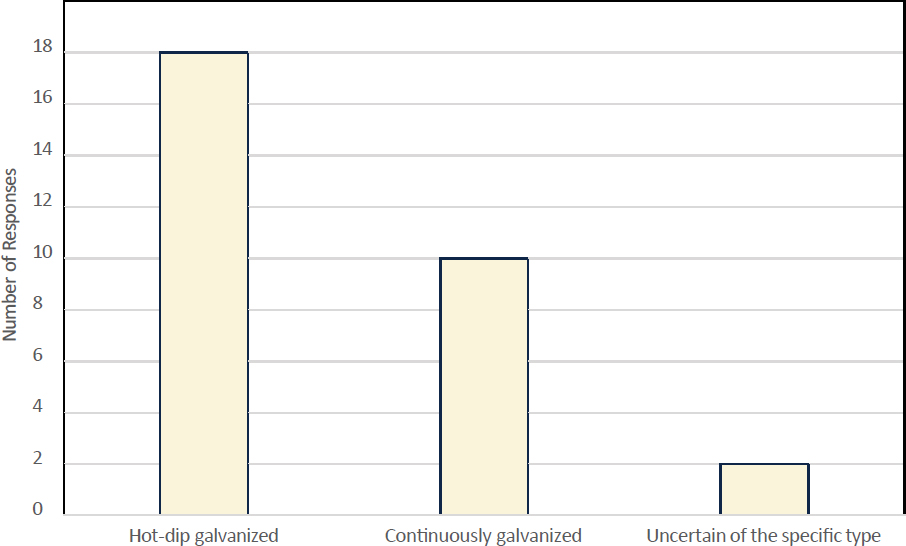

The survey respondents were queried regarding the type of galvanized bars that are used (hot-dip galvanizing, continuous galvanizing, or unknown). In total, 24 state DOTs indicated the use of one or more types of galvanized bars in response to this question. This is larger than the 17 state DOTs reporting that galvanized bars are part of typical practice based on the data in the Past, Present, and Possible Future Use section and the 20 state DOTs reporting the same in the By Geographic Region section. This is as expected, given that this data queried broader use (e.g., historical and atypical uses). Figure 3-20 shows that the majority (75% of the 24 state DOTs reporting galvanized bar use) use hot-dip galvanizing. Ten of the 18 state DOTs reporting the use of hot-dip galvanized bars presently use galvanized bars in typical practice.

The data in Figure 3-20 also show that continuously galvanized bars are not uncommon, with 10 state DOTs indicating that they have used this bar type (42% of the state DOTs that indicated they use galvanized bars). Eight of the 10 state DOTs reporting the use of continuously galvanized bars presently use galvanized bars in typical practice. Of those indicating that they have used galvanized bars, 25% have used both hot-dip and continuously galvanized bars.

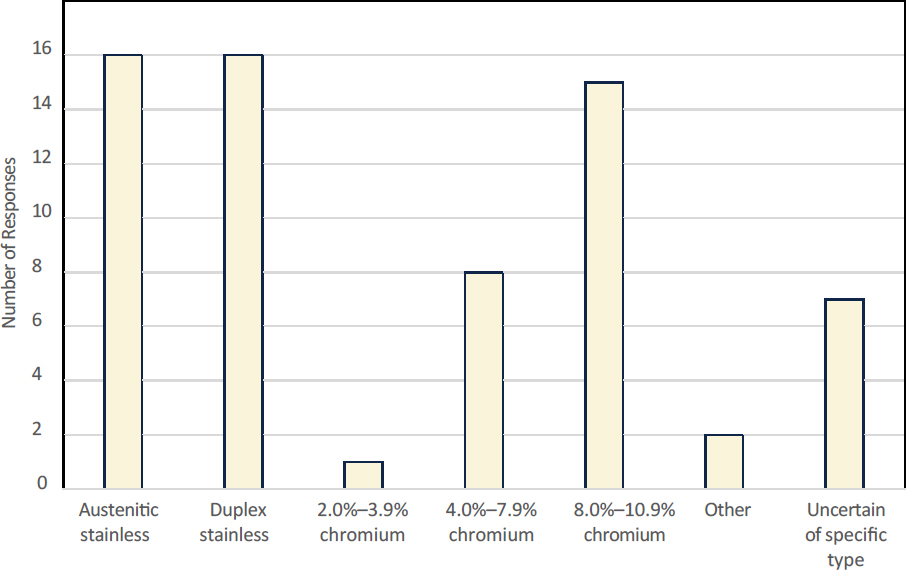

Figure 3-21 shows that of the stainless steel types that are commercially available, austenitic and duplex stainless steels have been used by an equal number of state DOTs. This data represents nine state DOTs that use both of these types of steel, seven that use austenitic stainless only, and seven that use duplex stainless only. Seven respondents indicated that they were uncertain of the specific type of stainless or chromium-alloyed steel used by their state DOT. With respect to the

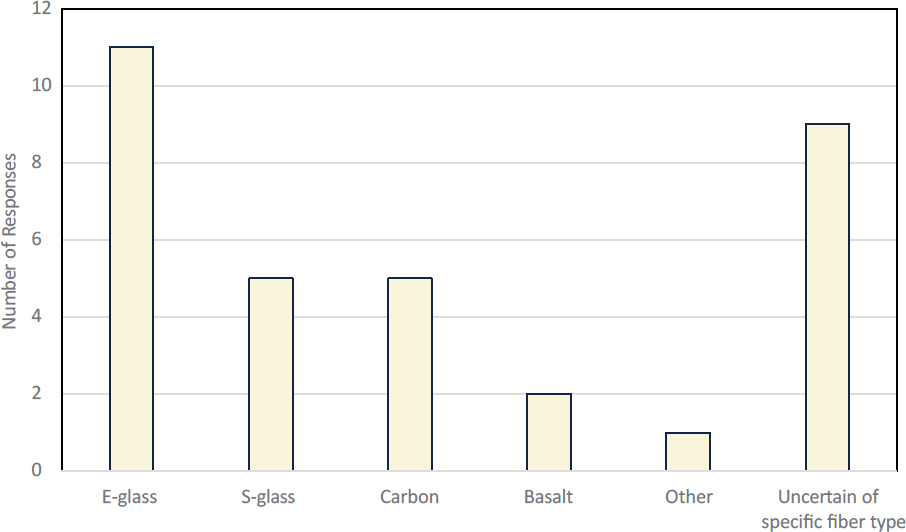

various options of chromium-alloyed steels that do not meet the requirements for stainless steel, Figure 3-21 shows that the bars with the highest chromium content (8% to 10.9%) are the most widely used (75% of state the DOTs using chromium-alloyed steel bars). A similar consideration of the types of FRP bars used is shown in Figure 3-22. This data shows that E-glass bars are the type of FRP bars with the most widespread use (44% of the 25 state DOTs indicating that they use FRP bars).

Decision-Making Processes

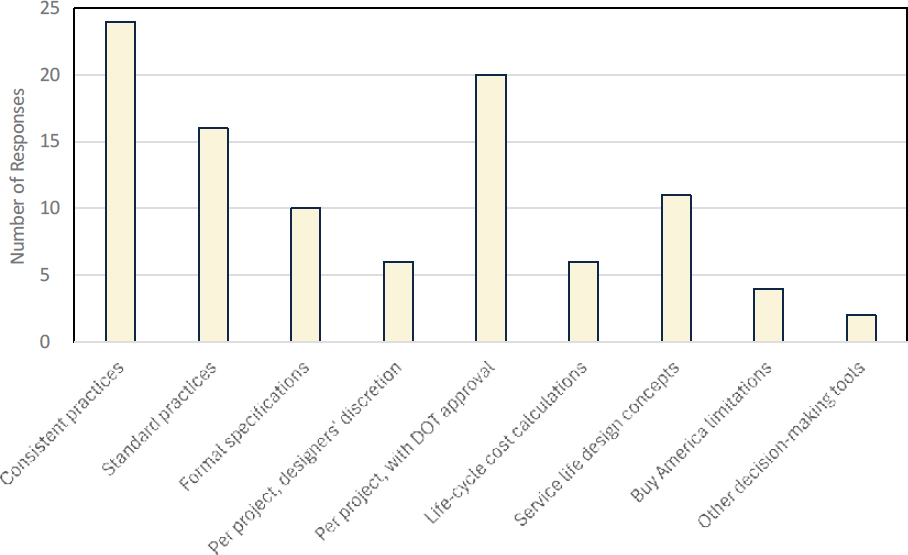

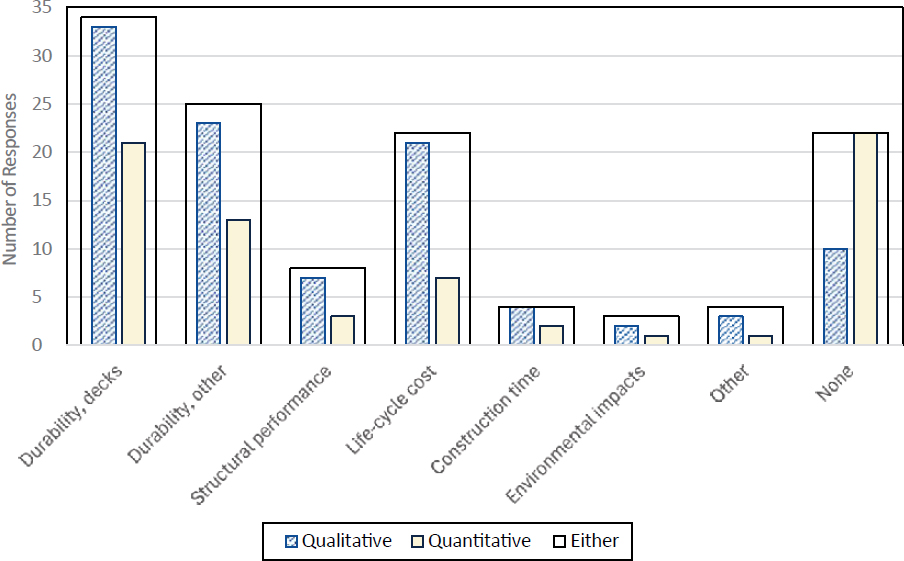

Figures 3-23 and 3-24 describe how state DOTs make decisions among the various types of reinforcing bars available. Figure 3-23 summarizes the decision-making process used, and Figure 3-24 summarizes the factors considered in these decision-making processes.

Figure 3-23 indicates that it is both common to have consistent practices for the majority of structures (53% of respondents) and to make decisions regarding CRRBs on a per-project basis with state DOT approval (44% of respondents). Having standard practices, using service life design concepts, and having formal specifications were the next most common answers, in that

order (with 22% to 36% of respondents choosing these options). CRRB selection based on the designers’ discretion, life-cycle cost calculations, or Buy America Act limitations were also indicated as factors in choosing among CRRBs, but not typically (9% to 13% of respondents). Other decision-making tools entered in response to this question were “[f]or decks, we have geographic region and route type maps to determine use of galvanized rebar. Coastal areas are on a case-by-case basis” and “[m]ajor complex bridges evaluated on case-by-case basis.”

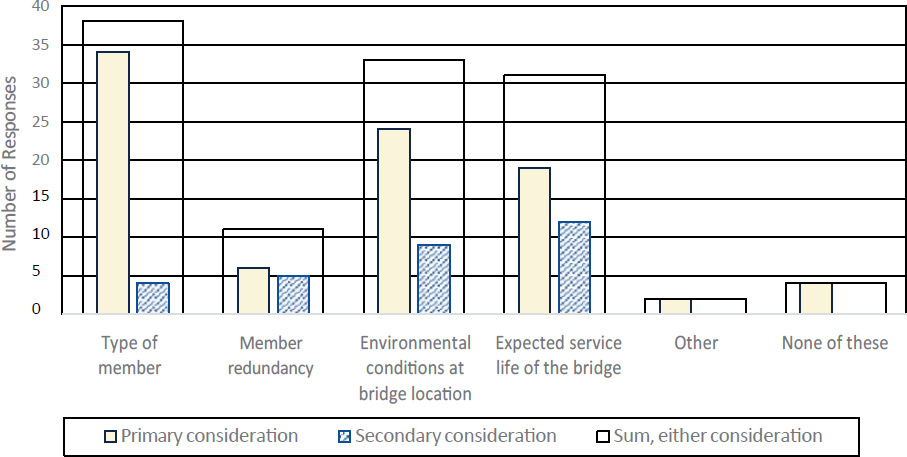

Figure 3-24 reports the number of state DOTs that consider the listed factors to be primary or secondary considerations in their process for determining reinforcing bar type. The “Sum, Either Consideration” data series in Figure 3-24 collectively considers the primary and secondary considerations. There was no limit on the number of factors that the respondents could select as either primary or secondary considerations.

Figure 3-24 shows that the majority of respondents consider both the type of member and the environmental conditions at the bridge location to be primary factors affecting the type of reinforcing bar specified (76% and 53%, respectively). For state DOTs that also consider these factors to be secondary considerations in prescribing a specific type of CRRB, these factors are considered by 84% and 73% of the respondents, respectively. Figure 3-24 also shows that most respondents (69%) consider the expected service life of the bridge to be a primary or secondary consideration in specifying reinforcing bar type. Member redundancy and other unspecified considerations were indicated by 24% and 4% of respondents, respectively. The instructions given with this question guided the respondents to choose the combination “none of these” and “primary consideration” if the same type of bars is used consistently throughout their state DOT. This combination may have also been selected for other reasons and was chosen by 9% of the respondents.

Design and Construction Considerations

This section reports the survey findings related to design and construction modifications made in association with using CRRBs. Design considerations related to concrete mix designs and cover are first discussed, followed by the procedures used to design members that are reinforced with FRP bars and then by discussion of state DOTs’ consideration of the effects of using metallic CRRBs on structural designs. Considerations of quality control for CRRBs during construction are also discussed.

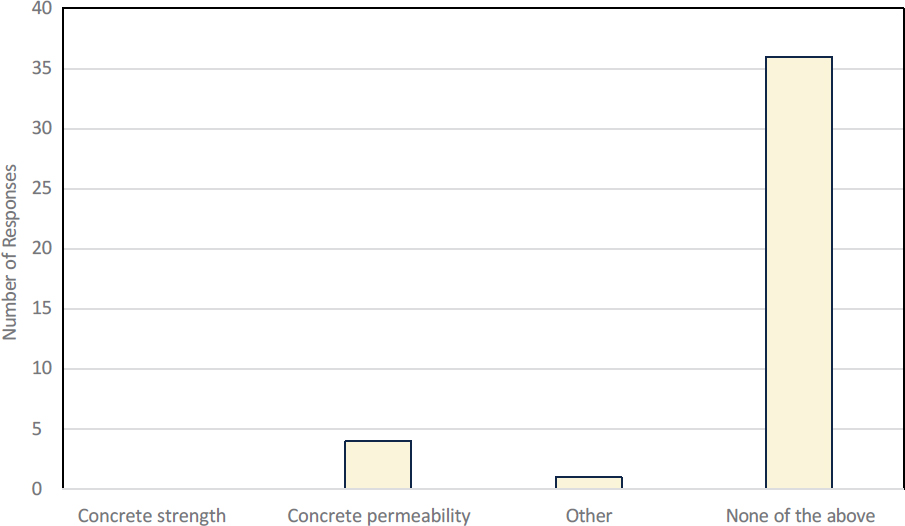

Concrete Specifications

Two categories of information regarding concrete specifications that were queried in the survey were mix design and cover depths. Figure 3-25 demonstrates that most state DOTs (82% of respondents) do not vary the concrete mix design based on the type of reinforcing bar used. Of those that do vary concrete mix design properties, concrete permeability was the only variable considered by more than one state DOT. In written survey responses, the removal of highly reactive pozzolans was also noted.

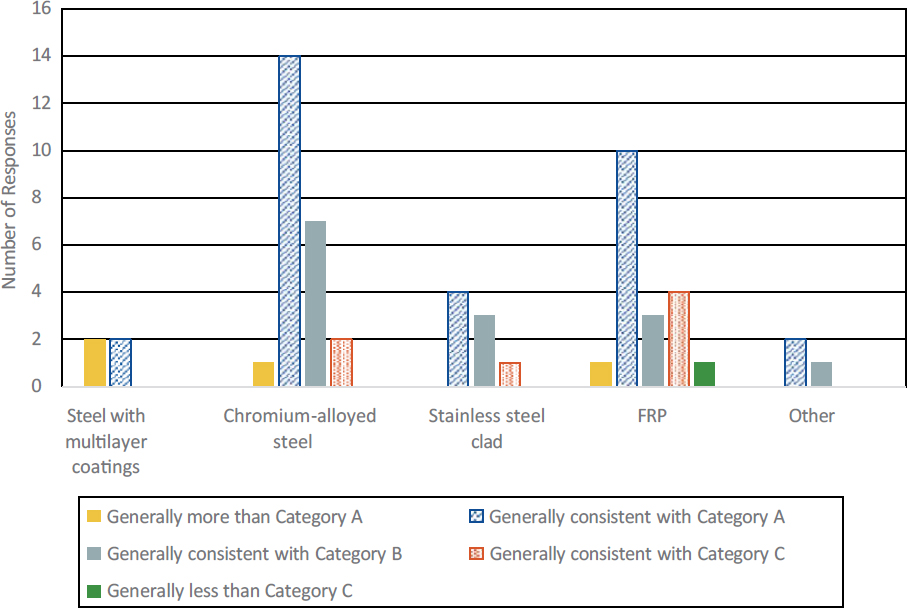

AASHTO LRFD BDS (AASHTO 2020a) gives minimum cover requirements in its Table 5.10.1-1. This table specifies alternative cover requirements for different exposure situations based on the reinforcing bar type used. Category A is black bars and therefore generally has the highest cover requirements. Category B represents epoxy-coated and galvanized bars. Category C is stainless steel bars and typically has the lowest cover requirements. Because this reference is silent on recommended cover depths for other bar types, it was of interest to determine what cover distances state DOTs had used for steel with multilayer coatings, chromium-alloyed steel, stainless steel clad, and FRP bars relative to these existing AASHTO categories.

Figure 3-26 shows that the most common answer for chromium-alloyed steel, stainless steel clad, FRP, and other reinforcing bars was “generally consistent with Category A” (i.e., aligned with

the maximum cover distance category given by AASHTO LRFD BDS). This option was also tied with “generally more than Category A” as the most common answer for the remaining bar type specified (steel with multilayer coatings). For all metallic bar types (which includes all bar types indicated in the “other” category), there is a decreasing number of responses as the cover distances move further away from these maximums. In contrast, the second most common answer for FRP bars is “generally consistent with Category C.” FRP is also the only bar type for which the option “generally less than Category C” was selected. It is speculated that these practices are chosen because FRP bars do not corrode and therefore may not benefit from providing larger cover distances, which are often based on the premise of delaying the time to corrosion initiation. In written responses, it was noted by one respondent that thinner bridge decks are permitted when using reinforcement other than epoxy-coated bars (from a state DOT that does not use black bars).

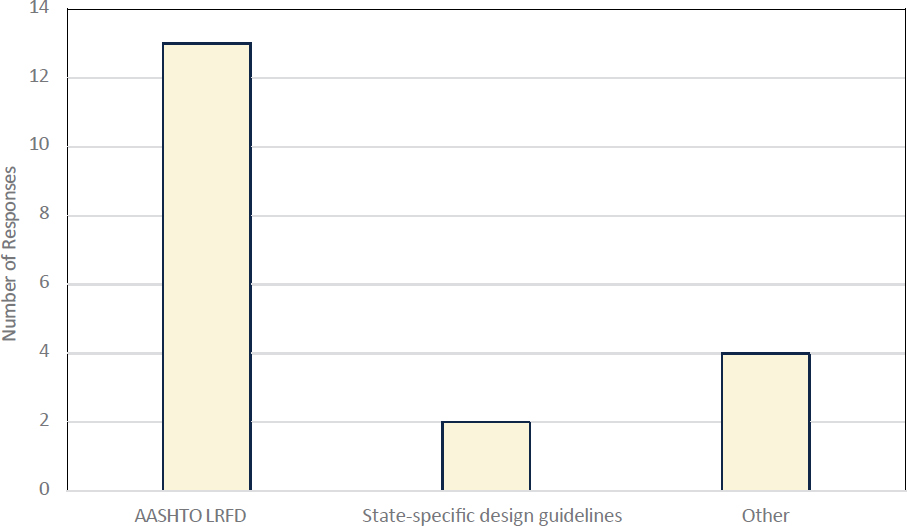

FRP Specifications

Of the 19 state DOTs that report using concrete members reinforced with FRP bars, Figure 3-27 demonstrates that most of these (68%) reported that they use the AASHTO LRFD Bridge Design Guide Specifications for GFRP-Reinforced Concrete (AASHTO 2018) to design these members. In addition to state-specific design guidelines, the ACI Guide for the Design and Construction of Structural Concrete Reinforced with FRP Bars (ACI 2006) was mentioned as another reference used.

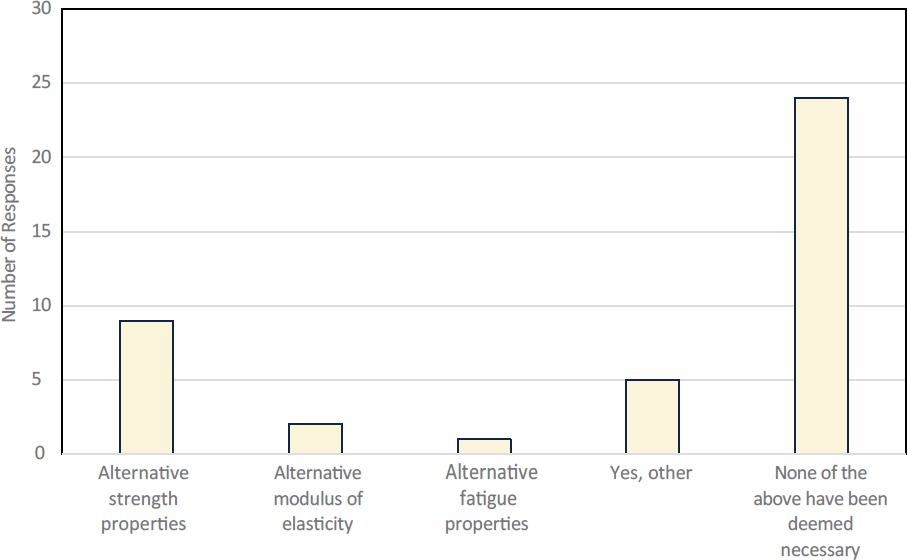

Modifications to Structural Designs

Figure 3-28 reports the types of alternative mechanical properties exhibited by some metallic CRRBs that have been considered in structural designs. It shows that these variabilities have generally not affected structural designs, but the most common variable considered is alternative strength properties. One respondent noted (in text responses) that the design strength in such situations is limited to 75 ksi. In the other responses received, splice and development lengths were also noted as being modified.

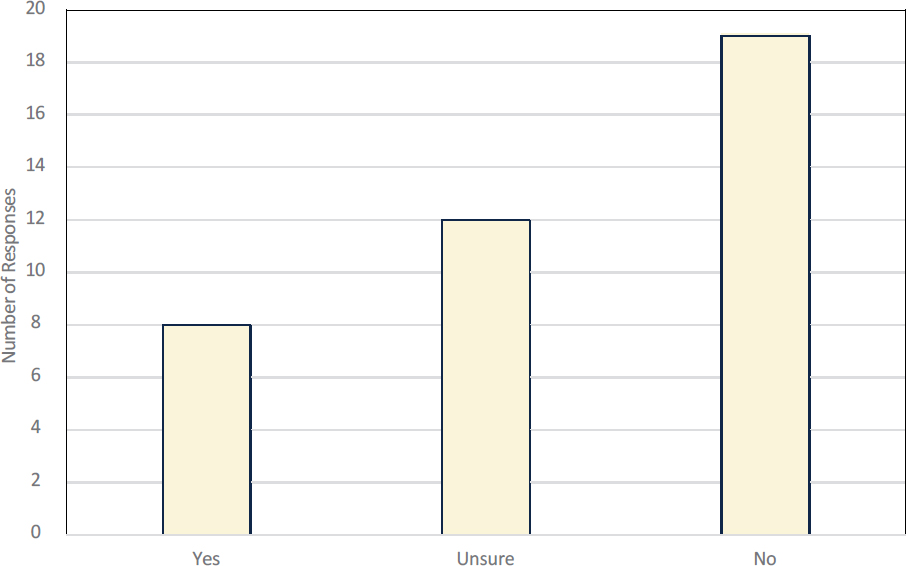

The data in Figure 3-29 show (of the state DOTs that use CRRBs) whether there have been improved efficiencies in the structural design of bridges because of using CRRBs. This could be a result of taking advantage of more favorable mechanical properties of some CRRBs or from other causes. Figure 3-29 shows that the common answer to this question was “no” (from 43% of the respondents to this question that reported using CRRBs), but “yes” and “unsure” were also common answers (18% and 27%, respectively). The bar types used by the respondents that answered

“no” to this question were evaluated to assess whether they had used bar types that were conducive to structural efficiencies. This analysis revealed that 13 of these 19 state DOTs had used either stainless or chromium-alloyed bars, which typically have higher strengths such that they may allow for some structural efficiencies. It is also noted that five state DOTs said that they do not use CRRBs in response to this question; these responses are not included in Figure 3-29.

Quality Control

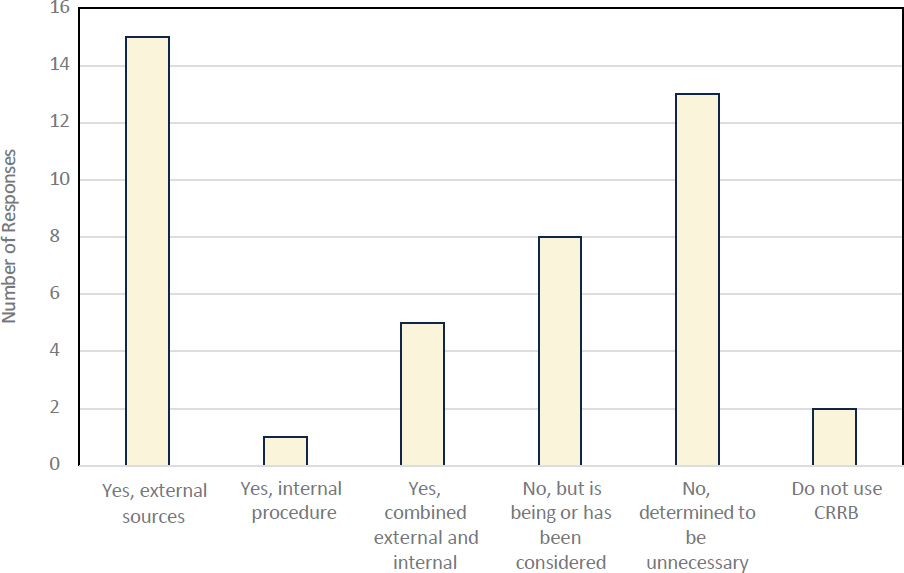

State DOTs were queried regarding whether revised quality control practices were used with CRRBs relative to typical practice. Figure 3-30 illustrates that the most common response to this question was that there were quality control procedures unique to some CRRB types that were based on guidelines from external sources (34% of the respondents to this question). It was also common (30% of responses) to report that the state DOT had determined that additional or alternative quality control methods for CRRBs were not needed. The bar types typically used by these state DOTs in present practice included all bar types within the present scope except stainless steel clad bars. This subset of 13 state DOTs (which had determined that additional quality control methods for CRRBs are not needed) use each type of CRRB in the same or higher proportions as the full dataset. This indicates that the lack of need for additional quality control was not limited to certain bar types and that it is based on levels of experience consistent with national averages. Other responses regarding quality control methods indicated that state DOTs used internally developed procedures, used procedures based on a combination of external and internal procedures, or that quality control of CRRBs was an ongoing consideration.

Limitations and Challenges

This section reviews data from three survey questions aimed at understanding the limitations and challenges experienced by state DOTs in using CRRBs. Limitations refer to an obstacle that limits specifying a given bar type; challenges refer to observed issues that have occurred during

use. Limitations are divided into two categories: uncertainties regarding performance metrics and practical limitations.

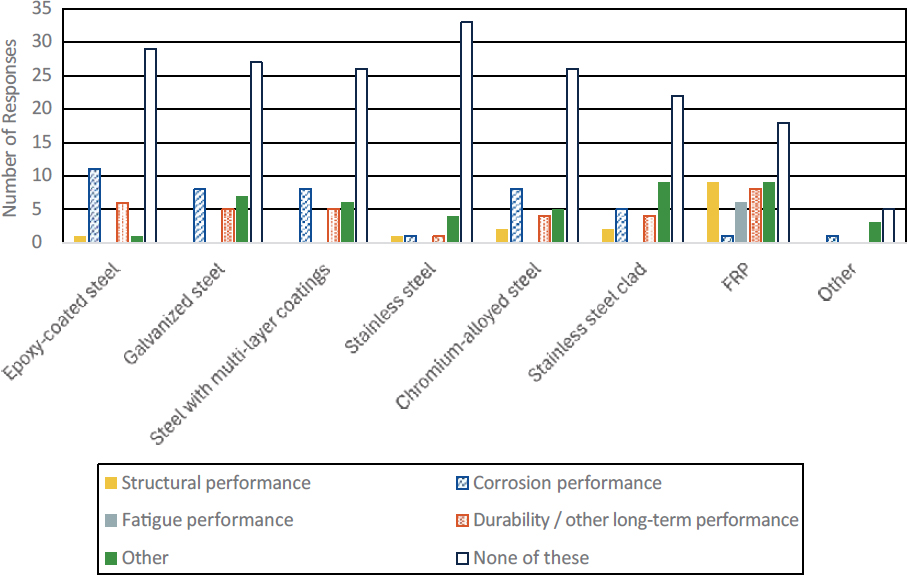

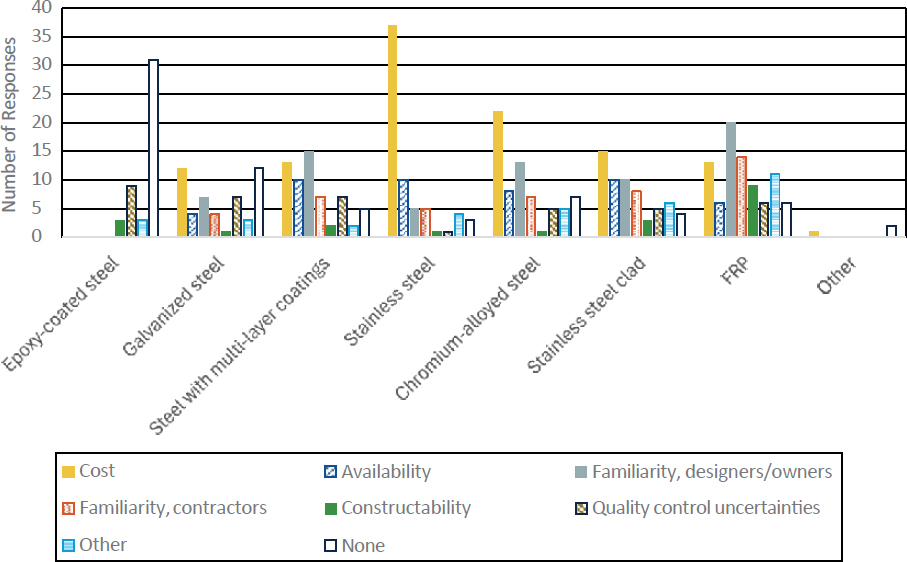

The first of these datasets is presented in Figure 3-31, which describes the data on performance uncertainties that have resulted in limitations in use. Figure 3-31 shows that such concerns have most often not limited the use of most types of CRRB. The bar type having the most uncertainties limiting its use is FRP, and the bar type least affected by such concerns is stainless steel.

In terms of the type of concerns indicated, corrosion performance is the most common concern (for epoxy-coated steel, galvanized steel, steel with multilayer coatings, and chromium-alloyed steel). For FRP bars, uncertainty regarding structural performance was the one most commonly attributed to limiting the use of this bar type. FRP is also the only bar type with fatigue performance indicated as a concern. Other unspecified concerns were reported by as many as 20% of the respondents for some bar types; this was the most commonly reported uncertainty limiting bar use for stainless steel, stainless steel clad, FRP (tied with structural performance), and other (for which epoxy-coated chromium-alloyed bars were the only type specified). Of these other concerns, the only ones pertaining to a specific bar type were (1) a concern regarding durability of the ends of stainless steel clad bars and (2) a concern regarding crash testing for rail barriers with FRP bars. Other concerns that were reported (but that were not mentioned in reference to a specific bar type) were fabrication consistency and availability.

Figure 3-32 shows the total number of state DOTs that indicated any uncertainty for each bar type depicted in Figure 3-31. For example, if a given state DOT indicated two different concerns for a given bar type, that is represented as one frequency of a state DOT having an uncertainty regarding that bar type. FRP is the bar type observed as having the most widespread uncertainties (from 53% of the respondents). Galvanized, chromium-alloyed, and stainless steel clad bars are the types with the next most frequent indication of concerns (noted by 36% of the respondents).

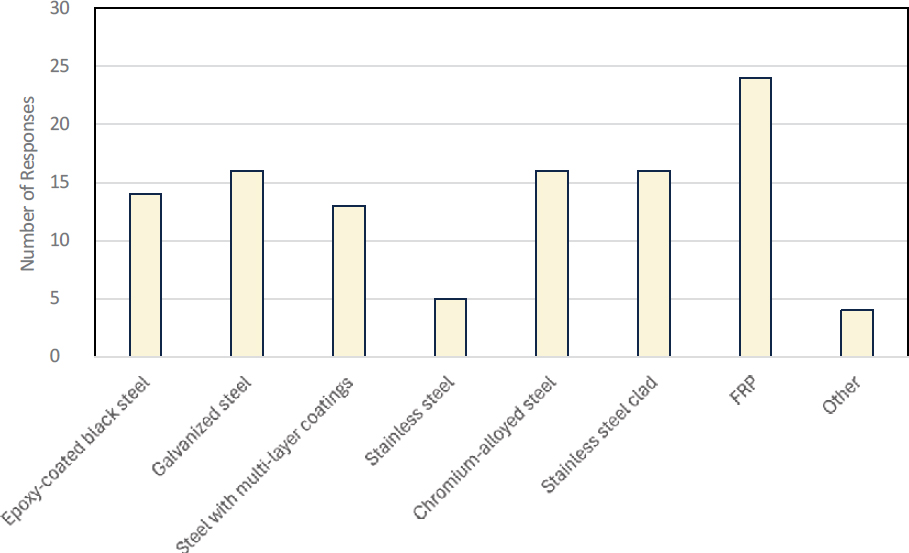

Figure 3-33 plots similar data focused on practical factors limiting the use of CRRBs. The cost of stainless steel was by far the most common limitation reported (by 73% of respondents) in this

survey. Another common answer was that epoxy-coated bars do not have any limitations (by 69% of respondents). The cost of chromium-alloyed steel and the familiarity of designers and owners with FRP were the next most common responses (by 49% and 44% of respondents, respectively). “Other” concerns were reported for all bar types listed but were typically not specified. The only concern given was related to the ease of causing damage to epoxy coatings during construction.

Another analysis of the data is provided in Table 3-1, where the primary and secondary practical factors limiting bar use are listed. Primary refers to the most common limitation and any other limitation that is within 50% of the response rate for the most common limitation for that bar type. Any other concerns receiving one or more responses are labeled as secondary limitations. Based on this analysis, cost is a primary limitation for all of the bar types with the exception of epoxy-coated bars. Familiarity of designers and owners is also a primary concern for the majority of bar types.

Figure 3-34 summarizes the data in Figure 3-33 using the same concept described for Figure 3-32. It shows similar trends, such as that stainless steel is the bar type with the most state DOTs indicating limitations and that epoxy-coated and other bar types received the fewest responses. These data add perspective to the data in Figure 3-33 by showing that the number of state DOTs experiencing limitations to the use of CRRB types other than stainless steel is relatively equal and relatively high at 58% to 69% (26 to 31 out of 45 respondents).

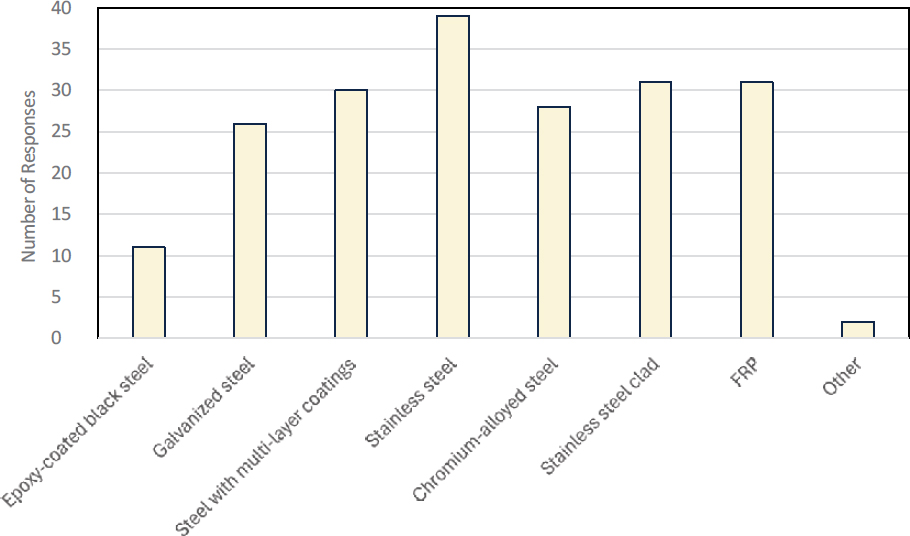

Figure 3-35 presents the data on observed problems in the field implementation of CRRBs. This question guided respondents to report problems that had been experienced (in contrast to only having a concern for a potential problem). Figure 3-35 shows that most respondents (51%) had not observed any challenges in the field implementation of CRRBs. Figure 3-35 also shows that the four most common challenges reported in the survey—field modifications of plans, galvanic corrosion caused by dissimilar materials, the specified material was not available, and other—were reported in relatively equal numbers (by 11% to 18% of respondents). “Challenges due to dissimilar coefficients of thermal expansion” was also an available option, but no

Table 3-1. Summary of practicalities limiting the use of CRRBs.

| Bar Type | Cost | Availability | Familiarity of Designers and Owners | Familiarity of Contractors | Constructability | Quality Control | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epoxy-coated | - | - | - | - | S | P | S |

| Galvanized | P | S | P | S | S | P | S |

| Steel with multilayer coatings | P | P | P | S | S | S | S |

| Stainless | P | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| Chromium-alloyed | P | S | P | S | S | S | S |

| Stainless steel clad | P | P | P | S | S | S | S |

| FRP | P | S | P | P | S | S | S |

| Other | P | - | - | - | - | - | - |

P = Primary

S = Secondary

respondents reported experiencing this issue. Responses supplied for other challenges included damage to epoxy coatings, the contractor failing to provide the specified material, extreme cost increase for stainless reinforcing, and rapid replacement of damaged bars.

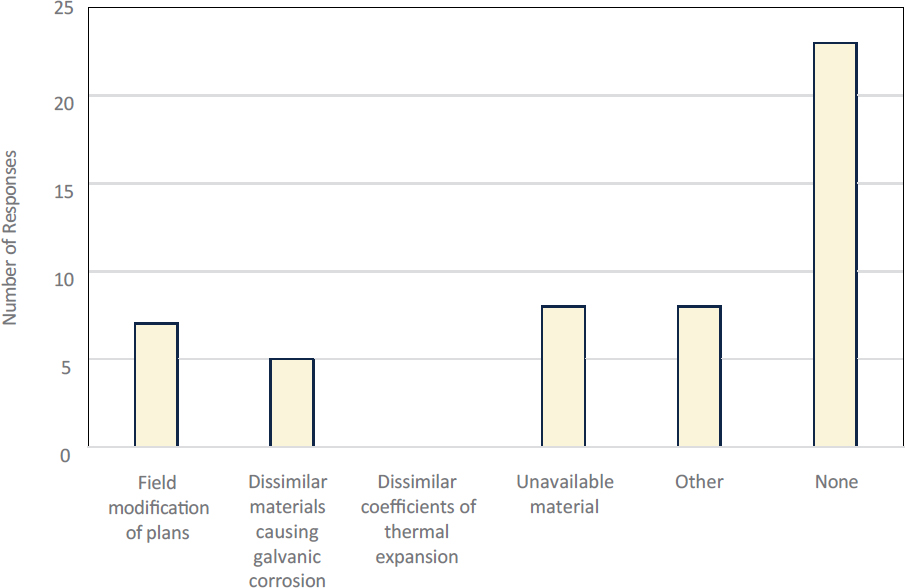

Benefits

Figure 3-36 summarizes the benefits of using CRRBs, which were reported in the survey through separate questions that asked the respondents to comment on benefits that been observed both qualitatively and quantitatively. Figure 3-36 also plots the total number of state DOTs that observed each of these benefits either qualitatively or quantitatively as a background series; the number differs from the direct sum of these two options because some state DOTs reported experiencing both categories of benefits. These data show that most respondents have experienced benefits in terms of improved durability of both decks and other components (76% and 56% of respondents, respectively). Multiple state DOTs also reported experiencing each of the other possible benefits given as options to this question: improved structural performance (18% of respondents), decreased life-cycle cost (49% of respondents), decreased construction time (9% of respondents), and decreased environmental impacts (7% of respondents). Other responses supplied by the respondents included reduced construction quality assurance required, improved seismic performance with some stainless alloys, and that CRRBs had not been use long enough to make an assessment. As expected, qualitative information on these benefits is more commonly available than quantitative information. Of the respondents, 22% reported observing none of these benefits of CRRBs, either qualitatively or quantitatively.

Implementation

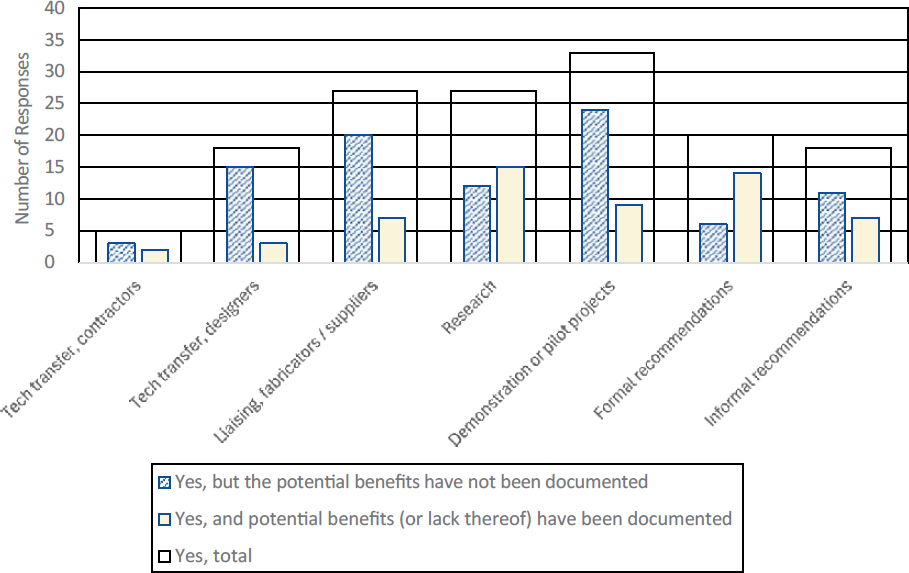

Figure 3-37 reports the frequency with which state DOTs have engaged in various types of implementation efforts related to CRRBs. The background series “Yes, total” indicates the number of state DOTs that have engaged in each type of implementation effort; the other data

series indicate whether or not the potential benefits of these activities have been documented. Figure 3-37 shows that the most common implementation activity is demonstration or pilot projects (73% of respondents). The majority of respondents have also performed research and liaised with fabricators or suppliers (60% of respondents for both activities). Formally and informally documenting recommendations (44% and 40% of respondents, respectively). When these two categories of implementation activities are considered together, this becomes as frequent as research and liaising with fabricators (60% of respondents each). Technology transfer aimed at designers was also a common activity (40% of respondents). Eleven percent of respondents had engaged in technology transfer with contractors.

For most of these activities, state DOTs have typically not documented the benefits (or lack thereof) of these activities. Case example participants were queried on this topic; those findings are described in Chapter 4.

Other

At the end of the survey, state DOTs were asked if they had any considerations for CRRBs that were not encompassed by the survey. Three respondents answered “yes” to this question. The brief (within the specified three-word limit) explanations that were given to elaborate on this were: stainless heavy traffic, support chairs, and reduced weight.