State DOT Policies and Practices on the Use of Corrosion-Resistant Reinforcing Bars (2025)

Chapter: 4 Case Examples

CHAPTER 4

Case Examples

This chapter contains detailed information on the practices and experiences of six state DOTs with respect to CRRBs. The participants are first described, followed by discussion of their practices related to selecting among the available types of CRRBs. Other considerations related to these choices (including specifications specific to certain bar types, modified concrete mix designs, other modifications to structural designs, and quality control procedures) are then described. Observed limitations and challenges related to using CRRBs and observed benefits of using CRRBs are then described in separate sections. Implementation efforts conducted by these state DOTs are next described. This chapter concludes by providing an outlook of the participants’ future plans with respect to CRRBs and what information is desired by these state DOTs to improve future practices associated with the use of CRRBs.

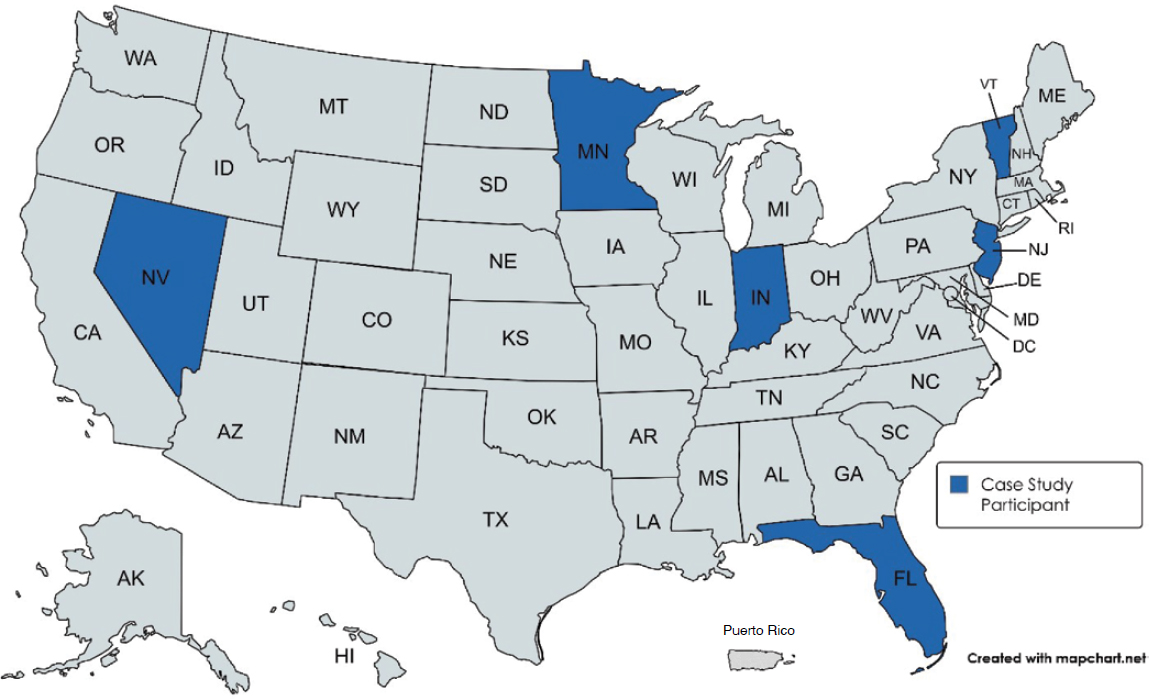

Participants

Six state DOTs participated in interviews, which collected the information that forms the basis of the case examples described in this section. As shown in Figure 4.1, these were the Florida, Indiana, Minnesota, New Jersey, and Nevada DOTs (FDOT, InDOT, MnDOT, NJDOT, and NDOT, respectively) as well as the Vermont Agency of Transportation (VTrans). These case example participants were selected by identifying a cohort of state DOTs that could collectively provide information on each of the subtopics of interest to this study and on each of the bar types in use in present practice as well as provide geographic diversity, with each of the four AASHTO regions (Northeast, South, Mid America, and West) represented. Because this project was largely motivated by the effects of the use of deicing chemicals, it was advantageous that the ideal cohort included additional state DOTs from the Northeast and Mid America regions (which generally have higher uses of deicing agents). The selection of FDOT as a participant was advantageous for representation of marine environments.

Standard Uses of CRRBs

All case example participants have specifications dictating or guiding the selection of reinforcing bar type. These specifications and their relevant sections are the following:

- FDOT Structures Manual. Volume 1, Section 1.4: Concrete and Environment (FDOT 2024a); and Volume 4, Section 2.1: Basalt and Glass Fiber Reinforced Polymer (BFRP, GFRP) and Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) Reinforcing Bars—Permitted Use (FDOT 2024b).

- InDOT Standard Specifications Division 700: Structures. Various sections throughout. (InDOT 2024).

- MnDOT Service Life Design Guide for Bridges. Section 3.3: Reinforcing Bar; Section 4.1: Decks; and Section 4.5: Substructures (MnDOT 2023).

- NDOT Structures Manual. Chapter 14: Concrete—Section 14.3.1: Reinforcement Steel, Subsection 14.3.1.6: Corrosion Protection (NDOT 2008).

- NJDOT Design Manual for Bridges and Structures. Section 26: Reinforcement Steel Details (2016).

- VTrans Structures Design Manual. Section 5.1.2.2: Types of Reinforcement Steel (VTrans 2010). VTrans has draft revisions to these specifications (VTrans 2024a) that contain Section 5.2.4.1: Reinforcement Levels and Section 5.2.4.2: Use Locations.

Table 4-1 summarizes the typical bar types used in the application of these specifications, with “primary” referring to the bar type most commonly used and “secondary” referring to other bar types allowed by the state DOTs’ specifications. These labels were established based on a review of the specifications cited previously and on discussion of typical practice provided by the case example participants, which are summarized in the following subsection. These practices are synthesized by describing the factors considered by the case example participants in their design practices with respect to CRRBs. A synthesis of these state DOTs’ perspectives on each of the bar types listed in Table 4-1 concludes this section.

Summary of State DOT Standards and Common Practices

This section summarizes each case example participant’s standards and common practices. A synthesis of these current approaches follows that summarizes the factors considered by each participating DOT in deciding between alternative bar types as well as the typical use of each bar type.

Table 4-1. Standard bar types.

| State DOT | Black | Epoxy-Coated Steel | Galvanized Steel | Chromium-Alloyed Steel | Stainless Steel | Stainless Steel Clad | Steel with Multilayer Coatings | Epoxy-Coated Chromium-Alloyed | Fiber-Reinforced Polymer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDOT | Primary | - | - | Secondary2, 3 | Secondary | - | - | - | Secondary |

| InDOT | Secondary | Primary | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MnDOT | Secondary | Primary | - | - | Secondary | - | - | Secondary | Secondary |

| NJDOT | Primary | Primary | Secondary | - | Secondary | Secondary2 | - | - | - |

| NDOT | Primary1 | Primary1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| VTrans | Secondary | Secondary | Primary | - | Secondary | Secondary | Secondary | - | Secondary |

1 NDOT varies primary rebar material by county.

2 Allowed per specifications, but not typically used.

3 Permitted for use as 100 ksi reinforcement; not considered for corrosion resistance.

InDOT

Bridge design, including reinforcing bar specifications, is governed in Indiana by InDOT’s Standard Specifications Division 700: Structures (InDOT 2024). These specifications require epoxy-coated steel in most situations (e.g., bridge decks, reinforced concrete boxes, and the stirrups of prestressed girders). The primary exception to this is that black bars may be used in piers if they are not under joints. External research sponsored by InDOT (Frosch et al. 2014; Labi et al. 2014) provided a rationale for these InDOT specifications.

InDOT uses epoxy-coated bars or a combination of black and epoxy-coated bars for typical bridges. However, stainless steel has been used in isolated large projects for which CRRBs were more thoroughly evaluated on a case-by-case basis. This is of interest when there is need for a more durable material, such as in areas with high traffic volume (and therefore a desire for longer service life and decreased future maintenance requirements).

NDOT

NDOT documents its policies regarding reinforcement in concrete bridge members in its Structures Manual, Section 14.3.1.6 (NDOT 2008). Either epoxy-coated or black bars are specified depending on geographic location and member type. With respect to geography, Nevada has a significant variation in climate throughout the state, and NDOT prescribes different bar types accordingly. For example, Clark County has a desert climate and therefore black bars are the default choice in this region. Clark County is home to the city of Las Vegas, a large urban center containing a significant percentage of the state’s bridge inventory. The remainder of the state DOT’s bridge inventory is in locations that are prone to the use of deicing agents. In these portions of the state, epoxy-coated rebar is required in members such as the top 1 foot of concrete (e.g., decks, rails, approach slabs, the top of webs of cast-in-place girders) and under deck joints. This is due to concerns regarding deicing agents and, in the case of decks, wear. Low-permeability concrete is required in parallel in these situations. These are legacy policies that have been in use for decades, with past and current NDOT observations supporting their effectiveness at balancing performance and cost.

There are few deviations from the NDOT standards, but a notable one is the use of epoxy- coated reinforcing bars in Clark County (where black bars would typically be used) for select project-specific requirements (e.g., when cover distances are less than typical). NDOT also typically provides a deck overlay within the first 10 years after construction and sometimes provides overlays (particularly when humidity is low) and waterproofing membranes during construction as part

of their efforts to extend the time until first maintenance. NDOT has historically utilized polymer concrete or thin bonded multilayer overlays. More recently, the agency has experimented with hybrid polymer deck overlays.

NJDOT

The NJDOT Design Manual for Bridges and Structures (NJDOT 2016) gives guidelines for rebar selection based on legacy practices that have evolved on the basis of service life and cost considerations. Section 26.1.2 lists types of structural components and locations within structures where CRRBs shall be provided; NJDOT uses black bars in other situations. Section 26.1.3 then defines the permitted types of CRRB to be epoxy-coated, galvanized, stainless steel, and stainless steel clad. Text in this section of the manual encourages designers to evaluate site-specific conditions and service life in choosing among these options.

General guidelines on consideration of site-specific conditions are given for structural steel in Section 24 of the manual. Definitions exist for four environmental zones for the state that are based on a combination of qualitative and quantitative criteria (found in Section 24.18.6). Quantitative definition of the splash zones for individual tidal rivers based on their measured salinity is also provided (in Section 24.18.3). Effects of deicing agents and exposure to leaking deck joints are also conceptually considered.

As a result of the practical application of these guidelines, epoxy-coated rebar is currently the predominant type of CRRB used by NJDOT. Galvanized bars are also commonly used. Stainless steel is used on select projects for which service life is a key consideration, but it is used selectively because of its cost. LCCA is sometimes done in these situations to verify whether there is justification for the up-front cost premium for stainless steel. Stainless steel clad is not typically used because of limited experience, uncertainties with performance, and lack of availability.

FDOT

Volume 1 of the FDOT Structures Manual discusses reinforcing bar selection in Section 1.4: Concrete and Environment. Reinforcing bar options are listed in subsection 1.4.1; Table 1.4.3-3 and the associated discussion specifies situations in which alternative reinforcing bar types should be considered. In Section 1.4.1, black bars are specified as the default reinforcing bar type. Stainless steel and chromium-alloyed steel bars are listed as options that are available with prior approval. Stainless steel is considered for its durability and strength properties, while chromium-alloyed steel bars are used for their strength benefit only and are not considered for applications where increased durability is desired. FDOT has also used FRP bars on many projects, with examples provided on the FDOT website (FDOT 2022). Volume 4 of the FDOT Structures Manual contains guidelines for designs using these reinforcing bars (FDOT 2024b). FDOT’s specifications were described as being the result of a 40-year process that considered durability research, the results of demonstration projects, and pragmatism. FDOT’s FRP reinforcing bar design guidelines and specifications were introduced in January 2015 after a two-year formal development effort that evolved with the introduction of FRP prestressed piling and associated structural elements. The specifications continue to be updated as national specifications are adopted and improved, such as AASHTO guide specifications (AASHTO 2009b; 2018), ASTM D7957 (ASTM 2022d) and the prior edition published in 2017, ACI 440.1R (ACI 2015) and the prior editions published in 2001 and 2006, and ACI CODE-440.11 (ACI 2022).

The typical reinforcement type in FDOT structures differs for substructures as compared to superstructures and decks based on different environmental classifications that are outlined in Section 1.3.1 of FDOT’s Structures Manual. Substructure components in the splash zone in extremely aggressive climates (the most severe of FDOT’s three climate categories) are typically

stainless steel or FRP in new designs. Piles that traverse out of water are typically stainless steel (or FRP prestressed) while pier caps are typically FRP; most of these are GFRP. FDOT’s experience is that GFRP is typically more economical than stainless steel reinforcing bars (with basalt FRP emerging as a competitive option). Stainless steel clad is also allowed in substructures but has limitations in availability; there are also concerns regarding the breach of the outer layer and the cut ends of these bars. For submerged substructure components, corrosion protection is provided by high concrete resistivity and cover thickness instead of CRRBs due to limited oxygen availability. The superstructure and deck reinforcement type is typically black bars unless it is located in a splash zone (including exposure to chloride-laden water spilling from trailered boats due to nearby boat ramps or beach access).

VTrans

VTrans outlines three corrosion resistance categories of reinforcing steel in its Structures Design Manual. In the current specifications, these are contained in Section 5.1.2.2: Types of Reinforcement Steel (VTrans 2010). Level I is labeled as “limited corrosion resistance” and consists of black and epoxy-coated reinforcing bars. Level II is labeled as “improved corrosion resistance” and consists of stainless steel clad and dual-coated reinforcing steel; draft revisions (VTrans 2024a) to these specifications add continuously galvanized and hot-dip galvanized to this category. Level III is labeled as “exceptional corrosion resistance” and consists of solid stainless steel bars; the draft revisions contain the addition of GFRP bars to this category. The basis for these categories is internal research simulating the effects of deicing agents (Tremblay and Colgrove 2013) supplemented with other relevant research. VTrans also has a guide for the design of GFRP-reinforced bridge decks (T.Y. Lin International 2016).

The level of corrosion resistance to be provided is mainly dictated by a combined consideration of the member type and the roadway classification. Three categories of roadway classification are given in the draft specifications, with interstates (including bridges supporting interstates or passing over interstates), structures on the National Highway System, and other sites requiring extended service life (e.g., 100 years) being the most severe category. State and Class 1 and Class 2 town highways are an intermediate category. Class 3 town highways, local roads, and private driveways comprise the least severe category. Within each of these roadway classifications, the corrosion protection level of the reinforcement that is specified varies primarily based on member type is shown in the manual’s Table 5.2.4.2-1. Considerations for ADT, splash zones, and shorter than typical service lives also dictate the final specification of corrosion resistance level.

The application of VTrans’s policies results in Level II reinforcement being specified in most of its bridge inventory. VTrans’s experience with bars in this category is that continuously galvanized reinforcing bars typically cost the least and perform well, so are often used. However, bars with more zinc may be used in some situations in which Level II bars are prescribed. Examples of factors considered in making this determination include ease of access, ability to perform phased construction, and detour lengths for future rehabilitation. Most situations for which Level III reinforcement is specified use stainless steel due to greater familiarity with this product, but some projects have used a combination of GFRP for the straight bars and stainless steel for the bent bars. However, VTrans speculates that the increasing cost of stainless steel reinforcing bars may promote a closer evaluation of GFRP reinforcing bars in future designs. VTrans is also piloting the use of the ChromX 9000 series (i.e., chromium-alloyed steel) reinforcing bars as a Level III reinforcement.

MnDOT

The MnDOT Service Life Design Guide for Bridges (MnDOT 2023) specifies rebar selection based on MnDOT’s past experience (including pilot projects and what has worked well for contractors), internal research, and review of selected external research as cited in the design guide.

The framework of MnDOT’s design guide is modeled after the AASHTO Guide Specification of Service Life Design of Highway Bridges (AASHTO 2020b). The FHWA Service Life Design Reference Guide (Hopper et al. 2022) provides additional examples of this philosophy’s implementation. MnDOT’s reinforcing bar selection is primarily based on the service life category (normal, enhanced, or maximum), the member type, and the site-specific exposure. Traffic volume is also considered as a factor in determining service life. Based on these factors, a combination of reinforcing bar type and cover distance is specified. Most situations are classified as having a normal service life. In these situations, epoxy-coated reinforcing bars are typically used. Black bars are typically used in buried footings where there is limited oxygen supply that could cause corrosion. In decks where enhanced service life is desired, epoxy-coated 4% Cr ASTM 1035 bars or GFRP bars are specified. For maximum service life of decks, stainless steel reinforcing bars are specified. For piers, a combined consideration of the service life and site-specific exposure to water and deicing agents is used to specify epoxy-coated, epoxy-coated 4% Cr ASTM 1035 bars, or stainless steel bars.

MnDOT’s design guide is generally viewed as the minimum standard, with districts and the state bridge office having the ability to discuss and implement more corrosion-resistant options on a case-by-case basis. More corrosion-resistant options may be selected for areas and projects that are not easily accessible for maintenance, where detour lengths are long, beneath open joints, and for precast box girders or segmental bridges where deck replacements are not viable. Conversely, the standards can be relaxed in isolated situations, such as when the need for greater durability is borderline and there is limited funding.

Synthesis of Decision-Making Criteria

A key item of interest in this study was to synthesize how state DOTs make decisions regarding the choice of CRRB. Table 4-2 summarizes the factors highlighted by the case example participants as key variables that are used to make decisions among alternative reinforcing bar types. The terminology used in Table 4.2 includes the following:

- “Directly” indicates that this is a factor directly incorporated into the state DOT’s specifications (listed at the beginning of the Standard Uses of CRRBs section) regarding selection of reinforcing bar type.

- “Indirectly” indicates that the state DOT views this to be (1) a factor affecting other variables listed in Table 4.2, (2) intrinsic to the philosophy of the approach used in its specifications, or (3) used on a case-by-case basis.

Table 4-2. Factors considered in reinforcing bar selection.

| State DOT | Member Type | Member Location | Environmental Exposure | Traffic Conditions | Expected Service Life | Member Redundancy | Location of Bridge Relative to Transportation Network | Life-Cycle Cost Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDOT | Directly | Directly | Directly | Situational | Indirectly | No | No | Situational |

| InDOT | Directly | No | No | Situational | Situational | No | No | Indirectly |

| MnDOT | Directly | Directly | Indirectly | Directly | Directly | Directly | Indirectly | Indirectly |

| NJDOT | Directly | Directly | Indirectly | No | Situational | No | Indirectly | Situational |

| NDOT | Directly | Directly | Directly | No | Indirectly | No | No | Indirectly |

| VTrans | Directly | Directly | Directly | Directly | Directly | No | Indirectly | Indirectly |

- “Situational” refers to a variable that is used to differing degrees on a case-by-case basis.

- “No” represents situations for which the listed variable is not a consideration affecting the type of reinforcement bar specified in the given state DOT.

Member Type

All case example participants consider the member type to some extent when determining the type of reinforcing bar specified. The most common examples of this are using reinforcing bar types that are expected to have more durability in members that are exposed to harsher conditions. Examples of this are decks treated with deicing agents (InDOT, MnDOT, NJDOT, NDOT, and VTrans) and substructure elements in splash zones (FDOT, MnDOT, and NJDOT) or under joints (InDOT, MnDOT, NJDOT, and NDOT). MnDOT also considers the necessary service life of superstructure components to specify more durable materials in box and segmental bridge girders because of the difficulty of undertaking deck replacements in these situations.

Member Location

Most case example participants consider that some member locations may experience increased exposure to chlorides, relative to other locations in the bridge. This is used as a criterion in directly or indirectly determining the reinforcing bar type. A common example of this is splash zones, including those from marine environments (FDOT) and from vehicular traffic on underpassing roadways treated with deicing agents (MnDOT and VTrans).

FDOT defines a marine splash zone in Section 1.4.3 of its Structures Manual as “the vertical distance from 4-feet below mean low water to 12-feet above mean high water and/or areas subject to wetting by personal watercraft (e.g., jet skis) or other activities and features” (FDOT 2024a). VTrans specifies more durable reinforcing bar options for some abutment components that are within 20 feet of the travel way in Table 5.2.4.2-1 of its draft specifications (VTrans 2024a). MnDOT defines extreme exposure as being within 15 feet of the edge of the driving lane and moderate exposure as being between 15 and 25 feet from the edge of the driving lane for piers. Depending on the corresponding service life, these exposure classifications can result in the specification of more durable reinforcing bar types.

Deck joints are another splash zone-like situation that can be created due to failing joints that create a local concentration of chlorides. NDOT and MnDOT specify providing reinforcing bars with increased durability under deck joints for this reason. Similarly, NJDOT uses CRRBs in the top mats of precast culverts if the fill is less than two feet and in the top and bottom mats of culverts if the top slab is used as a riding surface.

Environmental Exposure

Most of the case example participants consider environmental exposure to some extent when specifying the reinforcing bar type. Both NDOT and VTrans consider the variation in exposure to deicing agents throughout their state DOTs in prescribing alternative reinforcing bar types. NDOT considers this based on geography (i.e., the county in which the bridge is located), while VTrans considers this based on the roadway classification, with specific consideration of the traffic condition on and under the bridge. Both FDOT and NJDOT have specific definitions for environmental classifications within their state DOTs. These are indirectly used to inform reinforcement bar type selection in some situations. MnDOT considers the environmental exposure through microclimate effects represented by the combination of member type and member location described previously.

Traffic Conditions

MnDOT and VTrans explicitly consider traffic volume in prescribing types of reinforcing bars. For example, MnDOT uses an AADT of 60,000 or more as a criterion for enhanced service life

of decks and pier columns (MnDOT’s intermediate service life category). VTrans specifies that interstates and National Highway System (NHS) structures (which typically have relatively high AADT) to have their highest class of corrosion protection. VTrans also considers exceptionally low ADT (< 400) to be a criterion that can be used to relax durability requirements (relative to their typical procedures) in some situations. InDOT does not have formal specifications regarding the relationship between traffic conditions and reinforcing bar type but has used more durable options on a case-by-case basis for situations with exceptionally high AADT.

FDOT has a unique consideration with respect to traffic; it considers the type of traffic rather than the volume of traffic. Specifically, it requires additional consideration of reinforcing bar type in situations in which decks may be exposed to chloride-laden water spilling from trailered boats because of nearby boat ramps or beach access.

Expected Service Life

Targeting the intended service life is considered inherent to the design process of all case example participants. However, the level of formality and the scope of these considerations is variable among these state DOTs. MnDOT has a rigorous process for consideration of service life, with a dedicated design guide on this topic (MnDOT 2023). Three categories of service life are defined (normal, enhanced, or maximum), with corresponding criteria and reinforcing bar requirements. VTrans considers service life based on project cost and difficulty of maintenance, construction, or both. The reinforcement type for bridges that are classified as requiring extended service life based on these considerations are prescribed to be equal to VTrans’s most rigorous requirements for reinforcement type (i.e., the same as that used for interstates and NHS bridges). NDOT designs all of their structures to target a 75-year service life.

NJDOT and InDOT have explicitly considered service life in selected signature projects to result in the selection of more durable reinforcing bar types in these situations. NJDOT views more widespread use of service life design as an opportunity for optimizing future designs. FDOT anticipates the potential for increased use of CRRBs in the future as a result of increases in targeted service lives.

Member Redundancy

MnDOT was the only case example participant to consider member redundancy in their criteria for specifying reinforcement bar type. Because single column piers have less redundancy than multicolumn piers or pier walls, they are the only pier type designed for maximum service life. Consequently, for extreme exposure conditions (defined as within 15 feet of the driving lane), a more durable reinforcing bar (stainless steel compared to 4% chromium epoxy-coated) is required.

Location of Bridge Relative to Transportation Network

This variable is only indirectly considered and only by some case example participants (MnDOT, NJDOT, and VTrans). MnDOT and VTrans’s consideration of location of the bridge relative to the transportation network includes detour length, which in exceptional circumstances could be used to justify more corrosion-resistant reinforcing bar options. MnDOT and NJDOT also mentioned that although they do not directly consider this factor in their procedures, it is a factor affecting service life.

Life-Cycle Cost Analysis

Like expected service life, life-cycle cost is considered inherent to all case example participant practices with respect to CRRB. However, detailed LCCA has been done on only a limited basis and a standard process for performing these calculations does not presently exist. Among the

case example participants, the most progress on this topic was reported by FDOT and NJDOT, with both of these state DOTs using LCCA to verify the justification for the up-front costs of construction on projects in which a premium was paid for more durable reinforcing bar types.

One example of this is an LCCA performed for a 2023 NJDOT project that used Northeast Extreme Tee, Type D beams (NEXT D beams). Service life was an important consideration because of the high volume of traffic carried by the bridge and because the superstructure and the deck consisted of the same member when using these beams. Therefore, this LCCA assumed that a full-depth deck replacement would include replacing the entire superstructure. The LCCA evaluated four CRRB alternatives (epoxy-coated, galvanized, chromium-alloyed, and stainless steel) as well as active and passive cathodic protection systems. The analysis assumed costs and longevity for each CRRB alternative as summarized by the variable cost data, replacement periods, time periods for minor and major deck rehabilitation, and corresponding spall repair areas presented in Table 4.3.

Cost data for each CRRB alternative was based on recent bidding data and The Engineering News-Record’s Construction Cost Index in order to escalate previous costs to 2023 prices. Replacement periods are based on New York State DOT estimates; the 80-year estimate for stainless steel is believed to be conservative. This results in two deck and superstructure replacements for epoxy-coated and galvanized reinforcing bars and one deck replacement for chromium-alloyed and stainless steel reinforcing bars. Minor and major deck rehabilitations are assumed at the listed number of years after initial construction and reconstructions, with some alterations for practicality in the latter portion of the service life, to result in the listed number of rehabilitations and replacements. The constant assumptions for all CRRB alternatives were as follows:

- 100-year service life

- Inflation rate of 4.3% and federal interest rate of 5.0% based on the Trading Economics forecast

- 2,000 square feet of deck area

The results of this analysis indicated that the epoxy-coated and galvanized alternatives with active cathodic protection resulted in the lowest life-cycle cost. The next lowest life-cycle cost option was chromium-alloyed reinforcing bars. However, none of these alternatives was selected because of lower confidence in the assumptions made regarding these newer technologies and

Table 4-3. Example 2023 NJDOT LCCA assumptions and results for alternative CRRB types.

| CRRB Type | Epoxy-Coated | Galvanized | Chromium-Alloyed | Stainless |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRRB Cost ($/lb) | 3.00 | 3.27 | 4.09 | 6.10 |

| Superstructure Cost ($/ft2) | 333.00 | 336.00 | 344.00 | 373.00 |

| Minor Deck Rehabilitation Year | 15 | 15 | 20 | 20 |

| Major Deck Rehabilitation Year | 25 | 30 | 50 | 55 |

| Replacement Interval | 40 | 45 | 75 | 80 (conservative) |

| Number of Minor Rehabilitations | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Number of Major Rehabilitations | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Number of Replacements | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Minor Rehabilitation Repair Area (% of Deck Area) | 8 | 8 | 5 | 5 |

| Major Rehabilitation Repair Area (% of Deck Area) | 15 | 15 | 10 | 10 |

| Estimated Life-Cycle Cost ($M) | 3.53 | 3.45 | 2.45 | 2.53 |

because of the logistic concerns for maintaining the active cathodic protection system. The next lowest life-cycle cost option was stainless steel reinforcing bars, at only 3.6% more than the chromium-alloyed reinforcing bars option. Therefore, stainless steel was selected as the reinforcing bar type for the NEXT beams in this project due to the anticipated increased performance and the reduced future maintenance.

FDOT had considered standardizing an approach for performing these types of LCCAs but concluded that there were presently too many subjective variables and too much uncertainty regarding durability of different reinforcing bar types for this to be practical. However, several journal publications related to LCCA were developed from FDOT-sponsored work (Cadenazzi et al. 2019, 2020, 2021). In Florida, LCCAs are complicated by whether the bridge is state-owned or locally owned. This is because FDOT sometimes administers funding for construction costs of locally owned bridges, but the local agency is responsible for maintenance costs. Because of this situation, LCCA calculations from the perspective of a given owner can give different results than if the same entity is responsible for both construction and maintenance. For example, investing more state funding up-front for construction of low-maintenance or long-life local bridges would not reduce FDOT’s long-term financial liabilities.

VTrans, InDOT, MnDOT, and NDOT each reported that life-cycle cost was an indirect consideration that was fundamental to their practices. VTrans elaborated, noting that considerations such as the future cost of rehabilitation were commonly considered in their practices.

Synthesis of State Practices and Experiences by Bar Type

This section provides a synthesis of the case example participants’ use of each reinforcing bar type using the standards and common practices described in the previous subsection (Summary of State DOT Standards and Common Practices). This synthesis elaborates on the data summarized in Table 4-1 to discuss common and unique considerations for each bar type among the case example participants.

Black Steel

Black steel is a primary rebar type use by FDOT, NJDOT, and NDOT. Florida and Clark County, Nevada represent geographies that are not regularly subjected to deicing agents. NJDOT uses black bars in locations such as in concrete drilled shafts and piles, footings and pile or shaft caps, stems of abutments, wingwalls, retaining walls, pier columns and walls, precast box and three-sided culverts, and as mild reinforcement for precast-prestressed beams. Black bars are used by NDOT in other regions of Nevada and by the other case example participants in isolated situations that are similarly immune to the effects of deicing agents such as substructure elements that are not beneath joints (InDOT), buried components where there is limited oxygen supply (MnDOT and VTrans), and exceptionally low-volume roadways that are not regularly treated with deicing agents (VTrans).

Epoxy-Coated Steel

A main trend represented by the data in Table 4-1 is that epoxy-coated steel rebar is the most commonly used material among the case example participants. It is the default material for InDOT, MnDOT, NJDOT, and counties in NDOT where deicing agents are used (i.e., outside of Clark County, where black bars are used—as detailed in the Summary of State DOT Standards and Common Practices subsection).

In contrast, VTrans and FDOT consider the durability of epoxy-coated bars to be relatively low. For this reason, epoxy-coated bars are not a standard bar type used by FDOT. In VTrans’s tiered system of categorizing reinforcing bar durability, epoxy-coated bars are assigned to the same level of corrosion resistance category as are black bars (Level I), but more refined consideration of some

situations results in the specification of epoxy-coated reinforcing bars. This includes limited Level I situations in which more corrosion resistance relative to black bars is desired, and in exceptional situations where a higher durability level would typically be required. Examples of the former situation (higher durability Level I) in VTrans’s draft specifications include approach slabs and slabs of bridges that are not a part of the interstate or NHS or that otherwise require extended service life. Examples of the latter situation (exceptions to requiring Level II or Level III durability) are situations in which the ADT is < 400 such that the application of deicing agents is limited, or for rehabilitation projects in which the service life of the component is relatively short (e.g., 30 years or less).

Of the case example participants, only FDOT does not allow epoxy-coated rebar. This policy stems from experiences prior to 2000 in the Florida Keys, which led FDOT to the conclusion that the coating was unreliable due to construction damage to the coating. Although InDOT shared the view that the quality of early iterations of epoxy-coated bars was less than desired, these concerns have been addressed to their satisfaction through improved manufacturing quality and improved quality control. InDOT, NJDOT, and NDOT noted that damage to the epoxy coating during construction was a concern, but they mitigate these concerns through quality control methods.

A final topic with respect to epoxy-coated reinforcing bars is their use in combination with black bars. MnDOT’s experience with using epoxy-coated bars in combination with black bars within the deck was that it resulted in accelerated corrosion. This finding has also been demonstrated in experimental testing and has been attributed to the difference in electronic potential between these two bar types (as described in Chapter 2).

Galvanized Steel

Galvanized steel is the primary reinforcing bar type used by VTrans. In its three-tiered system of categorizing reinforcing bar durability, galvanized bars are classified as Level II. VTrans’s experience is that continuously galvanized reinforcing bars are typically the least costly and perform well, so this bar type is often used.

Galvanized steel reinforcing bars (hot dipped) are used on approximately 10% of NJDOT’s current projects, and NJDOT has specific quality control procedures for this bar type. NJDOT uses galvanized bars because they provide an intermediate level of durability (in this case between epoxy-coated and stainless steel reinforcing bars).

In contrast, MnDOT considers the performance of galvanized bars to be comparable to that of epoxy-coated bars based on their past experience. Because epoxy-coated bars are easier to procure, galvanized bars are not presently used by MnDOT, although it was acknowledged that new galvanizing techniques (i.e., continuously galvanized bars) may be a reason to reconsider this practice in the future. NDOT and FDOT also expressed concerns regarding the long-term durability of galvanized bars. FDOT’s concerns are based on testing performed by FDOT’s Corrosion Laboratory, which performed internal testing on hot-dip galvanized reinforcing bars in the 1990s and on a few samples of continuously galvanized reinforcing bars more recently. The general finding reported from this testing was that galvanized bars performed worse than black bars when the concrete contained a significant proportion of fly ash as a supplementary cementitious material.

Chromium-Alloyed and Epoxy-Coated Chromium-Alloyed Steel

None of the case example participants presently use these types of bars in new designs in the uncoated condition, although FDOT, InDOT, and VTrans have used them in isolated cases in prior designs. Only MnDOT presently uses this bar type (4% chromium ASTM A1035), but only with an epoxy coating. These bars are used as an option for decks with enhanced service life (the intermediate category of service life considered by MnDOT) and as their third most corrosion-resistant option of four design options for piers.

Stainless Steel

Most case example participants (FDOT, InDOT, MnDOT, NJDOT, and VTrans) use stainless steel in select circumstances (representative of the most extreme conditions). The main reasons for these extreme situations relate to environment (FDOT) and service life (InDOT, MnDOT, NJDOT, and VTrans). Specific examples of the situations for which stainless steel reinforcing bars include prescribed piles of substructures in marine environments (FDOT); most components of interstate, NHS, and other structures requiring greater than normal service lives (VTrans); decks on projects designated as having maximum service life (MnDOT); and large projects with long service lives (InDOT and NJDOT). FDOT and VTrans categorize the durability performance of stainless steel to be on par with that of FRP bars and make specific decisions about which of these options to use based on other factors, such as cost; specific application (e.g., bent or straight bars, structural member); and designer or contractor familiarity with the alternative products.

Stainless Steel Clad

Stainless steel clad reinforcing bars are allowed in the specifications of VTrans and NJDOT but are not typically used by either of these state DOTs. NJDOT elaborated that these bars are not presently cost-effective and that the DOT has limited experience employing this bar type. FDOT does not presently use stainless steel clad bars but has used them in the past and is considering their future use given the recent manufacturing innovations mentioned in Chapter 2 (McAlpine 2023). This consideration is motivated by the minimal use of chromium and nickel, representing a potentially more environmentally friendly alternative (compared to solid stainless bars) while also providing familiarity to designers (compared to FRP). However, FDOT has some concerns regarding material availability and the breach of the outer layer of the coating and at cut ends of these bars.

Steel with Multilayer Coatings

Only VTrans currently allows the use of this bar type in its specifications. It is designated as an option for Level II corrosion resistance but is not typically used due to limited availability. MnDOT’s limited evaluation of this bar type indicated that it was not more effective than their preferred bar types but was more difficult to procure.

FRP

Three of the case example participants (FDOT, MnDOT, and VTrans) allow FRP bars as an option in select situations. FRP bars are used by FDOT and VTrans in situations for which maximum durability is required (as an option instead of stainless steel). Both of these state DOTs have published design guidelines for the use of FRP bars (FDOT 2024b; T. Y. Lin International 2016). FDOT uses FRP bars as the primary rebar type for concrete elements located in the splash zone of their most severe environments (i.e., “extremely aggressive,” one of three environmental classifications). FDOT’s experience is that GFRP bars are typically more cost-effective than stainless steel bars. VTrans reports the opposite, but notes that this may change with the increasing cost of stainless steel bars and may be influenced by the conservatism in their specifications relative to those of Canada (Canadian Standards Association 2019), which are based on more experience and are less conservative.

Examples of situations in which these state DOTs use FRP bars include splash zones (FDOT) and situations requiring maximum service life (VTrans). MnDOT also allows the use of GFRP bars as an option for decks with enhanced service life (its intermediate service life category). Furthermore, InDOT has used FRP bars in isolated, experimental cases and NJDOT has an interest in using FRP bars in a future implementation project.

The case example participants highlighted challenges in implementing the use of FRP reinforcing bars because of their unique characteristics when compared to metallic bars. VTrans and FDOT

have design guides on FRP reinforcing bars. VTrans’s experience is that these design guides are helpful, but designing with FRP involves fundamentally different concepts that many designers are unfamiliar with. NJDOT shared this perception of a lack of familiarity, which it believes leads to a challenge to be confident about the benefits that FRP bars may provide. MnDOT had similar concerns regarding lack of procedures for future repairs and concerns regarding performance during vehicular impacts.

The cost of FRP reinforcing bars was mentioned as another obstacle to more widespread use of this bar type (by MnDOT, VTrans, and FDOT). Factors mentioned as contributing to this cost include the relatively small number of GFRP suppliers, which results in a lack of competition that could drive prices down (VTrans). Other cost factors discussed were the cost of testing FRP bars due to the limited number of facilities available for this purpose. Increased construction time due to greater handling and storage requirements as well as tying time for the increased number of ties required were also mentioned as cost factors. VTrans also mentioned that reducing the conservatism of their GFRP guide could help with economics of GFRP. MnDOT raised similar questions regarding how to better leverage the capacity of higher-strength FRP bars.

Design and Construction Modifications

One of the goals of this study was to determine modifications to standard practices when specifying different CRRBs. The examples of such modifications that were discussed by the case example participants are summarized in the following subsections according to the following categories: concrete specifications, structural design modifications that occur due to alternative material properties, modifications that occur due to the coating properties of coated bars, and quality control procedures.

Concrete Specifications

NDOT considers the concrete specifications in parallel with the choice of CRRB. In most situations for which epoxy-coated reinforcing bars are used, NDOT specifies concrete with low permeability (designated as Class E or EA) (NDOT 2019). FDOT (2024a) requires concrete with higher resistivity as well as reduced permeability in some more aggressive climates (shown in Table 1.4.3-1 of their Structures Manual) although this is not directly tied to selection of reinforcing bar type.

The AASHTO LRFD Bridge Design Specifications specify the minimum cover for main reinforcing steel as a function of bar type, environment, member type, and other situations in its Table 5.10.1-1. MnDOT supplements these considerations with enhanced and maximum service life and includes consideration of piers in all service life categories (in Section 4.1.1 and in Table 2, respectively, of their Service Life Design Guide for Bridges) and in some cases uses variable cover depths depending on the bar type selected (MnDOT 2023). The FDOT Structures Manual (2024a) has alternative cover requirements based on more refined considerations of the local environment (relative to AASHTO) in Table 1.4.2-1. VTrans and NDOT also have cover requirements unique to their DOTs in Table 5.1.2.6-1 of the VTrans Structures Design Manual (VTrans 2010) and Figure 14.3-B of the NDOT Structures Manual (NDOT 2008) that are generally equal to the maximum cover distances specified by AASHTO (or slightly higher in some VTrans situations).

Modifications Based on Material Properties of Bars

The greatest deviations in material properties (relative to standard black bars) occurs for stainless steel, chromium-alloyed steel, and FRP bars. Several case example participants (FDOT, MnDOT, and VTrans) have leveraged the additional strength of stainless and chromium-alloyed steel bars to varying degrees in order to reduce the number of bars or overall area of reinforcement. FDOT uses

a yield strength of 75 ksi for stainless steel and MnDOT similarly utilizes some of the additional strength provided by these bar types, but not necessarily up to the yield strengths reported in the material specifications of these bar types. VTrans has used 100 ksi chromium-alloyed bars in select situations when there were concerns regarding the ability to adequately vibrate the concrete in pier designs with more bars. Structural designs can be readily modified by structural engineers based on these revised strength properties. There were questions raised by MnDOT regarding how utilizing these higher strengths may affect crack widths, particularly in decks (e.g., when using 60% of the yield stress for service limit states) and potential consequences of these crack widths relative to the goal of achieving improved durability with these bar types.

A significant difference between designing with FRP bars and designing with metallic bars is the lower modulus of elasticity and the lack of ductility of FRP bars. For FRP bars meeting the requirements of ASTM D7957 and D8505, the minimum modulus of elasticity is 6,500 or 8,700 ksi, respectively, compared to 29,000 ksi for steel reinforcing bars (see Chapter 2 for additional discussion on comparison of mechanical properties). The 2018 AASHTO LRFD Bridge Design Guide Specifications for GFRP-Reinforced Concrete describes the unique material properties of FRP bars and their application to the design of reinforced concrete members. Specific topics discussed include material properties; limit states (including strength, service, fatigue, creep, and extreme event); design for various stress states; specific considerations for various member types; and construction specifications (AASHTO 2018).

FDOT and VTrans also have state-specific documents on the use of FRP. Volume 4 of the FDOT Structures Manual (FDOT 2024b) specifies that all concrete members containing GFRP and basalt FRP reinforcing bars must be designed in accordance with the AASHTO LRFD Bridge Design Guide Specifications for GFRP-Reinforced Concrete (AASHTO 2018). The FDOT specifications supplement the AASHTO specifications, listing information such as general requirements, permitted uses of FRP reinforcing bars, and cover depths. VTrans also has guidelines for the design of GFRP-reinforced decks (T. Y. Lin International 2016). Topics include use cases, material properties, design considerations, cover depths, development lengths, and design details.

FDOT has also completed several demonstration projects on the use of FRP, which are summarized on its website (FDOT 2022). One of these projects is the Halls River Bridge Replacement Project. A more detailed publication on this project gives example design assumptions, resistance factors, development lengths, and structural details (Claure et al. 2017).

Modifications Based on Coating Properties of Bars

NJDOT and VTrans require that galvanized bars be bent prior to coating in order to prevent cracking of the galvanized coating per the preferred practice noted in ASTM A767. AASHTO LRFD Bridge Design Specifications prescribe increased lap lengths and development lengths for epoxy- coated bars in tension (relative to other bar types) in Sections 4.10.8.2.1b, 5.10.8.2.4b, and 5.10.8.4.3a (AASHTO 2020a).

Quality Control

Quality control of reinforcing bars is described by several national and international standards. At the material level, ASTM or AASHTO specifications (or both) exist for all bar types considered in the scope of this work with the exception of steel bars with multilayer coatings. These material specifications are also incorporated by reference in Section 9 (Reinforcing Steel) of the AASHTO LRFD Bridge Construction Specifications (AASHTO 2020c). InDOT and NDOT use qualified product lists for epoxy-coated bars (and also uncoated bars in the case of InDOT) as another means of quality control for these materials.

The AASHTO LRFD Bridge Construction Specifications document also covers quality control issues during fabrication (such as bending) and construction (including handling, on-site storing, and surface condition). Storing requirements included in these specifications require epoxy-coated reinforcing bars to be protected from sunlight, salt spray, and weather once delivered to the job site (AASHTO 2020c). In contrast, InDOT’s specifications allow unprotected storage for up to 21 days. However, enforcement of this specification can be a challenge. NJDOT allows for unprotected storage for up to 60 days.

The surface condition of coated bars is a critical aspect of quality control in order for these bar types to function as intended; this was mentioned by several case example participants (InDOT, NJDOT, NDOT, and VTrans). These DOTs have additional or alternative specifications relative to the AASHTO specifications, which have a tolerance of 2% of the surface area in each linear foot of bar length for epoxy-coated bars (AASHTO 2020c). In addition to the AASHTO damage tolerances for epoxy-coated bars, InDOT specifications require repairs on all damaged areas larger than ¼- × ¼-inch and rejecting any bars for which the repaired coating exceeds 5% of the nominal surface area of the bar. More strictly, VTrans and NJDOT require all damaged areas to be repaired (VTrans 2024b). NJDOT also requires inspections and repair (if necessary) at the time of coating, following ASTM A775 (ASTM 2022b), which limits the maximum repaired area to 1% of the total surface area in each 1-foot length of bar prior to acceptance. Field repairs are limited to less than six damaged areas in any 10-foot length of bar and a total surface area of four-square inches (NJDOT 2019). AASHTO, NJDOT, and InDOT specify that bars with damage exceeding these tolerances should be rejected, while those with damage lower than these tolerances may be repaired in accordance with AASHTO M 317, ASTM D3963, and ASTM A775 (AASHTO 2001; ASTM 1999, 2022). Note that AASHTO M 317 is now withdrawn and has been replaced with ASTM D3963; ASTM D3963 and ASTM A775 are companion documents.

VTrans specifications also contain provisions for repairing cut ends of all coated bar types. For galvanized bars, NJDOT has the same tolerances as their epoxy-coated tolerances and requires galvanized bars to be repaired based on ASTM A780 (VTrans 2024b; ASTM 2020b). NJDOT also noted that when stainless steel is used, quality control for these bars is dictated by special provisions. As a final note on the quality control of metallic bars, VTrans specifications contain the requirement to physically separate bar types on site when multiple types are used in different components of the same project (VTrans 2024b).

For quality control of FRP materials, VTrans (T.Y. Lin International 2016) incorporates by reference the (now superseded) AASHTO LRFD Bridge Design Guide Specifications for GFRP-Reinforced Concrete Bridge Decks and Traffic Railings (AASHTO 2009b). VTrans also contains a list of prequalified suppliers (T.Y. Lin International 2016). Similarly, FDOT maintains a quality assurance program for FRP suppliers that includes initial qualification testing as well as project verification testing and annual FDOT audits and inspections similar to the AASHTO Product Evaluation and Audit Solutions Composite Concrete Reinforcements program. MnDOT’s quality control procedures are reviewed for each FRP project; past FRP projects were based on Ontario Ministry of Transportation practices.

Limitations and Challenges

Limitations for specific bar types were discussed in the Synthesis of State Practices and Experiences by Bar Type subsection; the scope of this section is to summarize the limitations and challenges of CRRBs that the case example participants have experienced at different project stages.

Design

Most of the design challenges related to CRRBs relate to FRP bars as a result of the relative lack of familiarity with this material type compared to familiarity with metallic bars. FDOT

also noted the lack of reliable design software and guidelines detailing the practices for FRP bars. Design uncertainties regarding the strengths that should be used in design calculations for higher-strength metallic bars that lack a clearly defined yield point were also discussed in reference to additional information that would be desirable to the case example participants. These comments are elaborated in the Future Outlook section that concludes this chapter. NJDOT commented on the challenge of trying and embracing new materials and methods. Specific examples cited were FRP reinforcing bars and service life design concepts.

Procurement

The case example participants have experienced limited challenges with material availability. Although global supply chain issues have occasionally affected the supply of stainless steel (for InDOT) and basalt FRP (for FDOT) bars, these are not viewed as ongoing challenges. FDOT expressed ongoing concerns regarding the availability of stainless steel clad bars. A related concept to procurement is cost, with InDOT and NDOT stating that the cost of CRRBs other than epoxy-coated bars was generally difficult (for InDOT) or not possible (for NDOT) to justify.

Construction

Two types of construction challenges were experienced by the case example participants: field modifications to plans and quality control. The primary challenge related resulting from field modifications to plans was lead time issues for FRP and coated bars, assuming there are errors or other required on-site modifications. FRP bars can only be formed into bent shapes during the initial manufacturing process (pultrusion) with delayed thermoset resin curing. Similarly, hot-dip galvanized bars must be bent prior to coating in VTrans’s specifications (and is a recommended practice in ASTM standards), resulting in potentially significant lead times when field modifications are required. Similarly, NDOT has experienced weeks of delay time for epoxy-coated bars when field modifications were required. Quality control of coated bars that are cut in the field (therefore removing their coating from the ends of the bars) is an additional consideration. Although field repairs in these situations are common, InDOT expressed concerns that they lead to a lower quality coating.

Benefits

All case example participants report anecdotal evidence that their present CRRB selections are effective at improving durability based on a lack of currently observed problems (in contrast to past experiences). Specific examples cited included improved deck durability (MnDOT), the need for fewer repairs (NJDOT), the performance and periodic monitoring observations of demonstration projects using FRP, stainless steel, and chromium-alloyed steel (FDOT), and lack of spalling on reinforced concrete members (NDOT). These comments often considered the timescale over which different types of CRRBs had been used. For example, InDOT and NJDOT noted that epoxy-coated bars had been in use for decades, giving some confidence in long-term performance for the situations in which these state DOTs used them. VTrans noted that their bar selection process led to improvements relative to past practice on Vermont interstates (which have the harshest conditions in the state), but it was too soon to determine whether the targeted service lives would be met.

No case example participants had quantified documentation available on the performance of CRRBs. However, it was noted by NJDOT that the reinforcing type is often recorded in the NBI, so there is potential for this to be quantitatively evaluated in the future. Item 108C of FHWA’s Recording and Coding Guide for the Structure Inventory and Appraisal of the Nation’s Bridges (FHWA 1995) has the following coding items available with respect to reinforcing types: (1) epoxy-coated reinforcing, (2) galvanized reinforcing, (3) other coated reinforcing, and (4) other. FDOT has

quantified the rehabilitation cost of providing galvanic jackets to piers that did not contain CRRBs at $100M, which is an expense that could potentially be avoided by using CRRBs.

Several case example participants discussed secondary benefits that arise from improved durability. A specific example of this was a lower need for maintenance and fewer road closures (MnDOT, NJDOT, and VTrans). NJDOT and FDOT also mentioned the reduced environmental impact and reduced life-cycle costs that result from improved durability. FDOT also noted that increases in expected design life motivates the increasing use of CRRBs.

Implementation

Implementation efforts considered in this data collection effort included demonstration and pilot projects, research, development of guidelines and policies, technology transfer activities, and other leadership activities. Collectively, the case example participants have engaged in each of these types of efforts. Their experiences on these topics, all of which were viewed positively, is described in qualitative terms. No quantitative information to assess the relative success or effectiveness of these efforts was readily available.

Demonstration and Pilot Projects

Most of the case example participants (FDOT, InDOT, MnDOT, and VTrans) have completed pilot or demonstration projects using CRRBs. FDOT, InDOT, and MnDOT have included the implementation of FRP reinforcing bars; VTrans completed a Highways for Life project using stainless steel (in conjunction with FHWA) in 2010. Although there is typically little information available on these projects, MnDOT is developing a feature for their bridge inspection program to track the unique features of pilot projects in the future via element-level inspection items. FDOT documents a long list of demonstration and pilot projects on the department website (FDOT 2022). FDOT has found these types of projects to serve a valuable role for promoting familiarity and also found that their efforts to implement the use of CRRBs progressed more rapidly with the publication of developmental standards.

Research

Most case example participants have engaged in or supported research on CRRBs. Examples include studies supported by InDOT, NJDOT, and VTrans (Weed 1980; Tremblay and Colgrove 2013; Frosch et al. 2014; Bandelt et al. 2023), which evaluated the comparative corrosion performance of a variety of CRRBs. The InDOT research also included LCCAs for CRRBs in a complementary publication (Labi et al. 2014). These studies were specifically cited by InDOT, NJDOT, and VTrans as being informative to their existing practices with respect to CRRBs. Similarly, MnDOT has supported research to verify their recommended practices regarding GFRP reinforcing bars (Shafei et al. 2020, 2023).

FDOT has supported an extensive body of research on the use of FRP reinforcing bars, which is well-documented on the department website (FDOT 2022). The research portion of the FDOT website is organized by material type. The research on basalt FRP reinforcing bars contains content on testing methods, durability findings, and standardization processes. A section on GFRP reinforcing bars contains reports on performance evaluations based on field and laboratory studies.

Guidelines and Policies

Most of the case example participants (MnDOT, NJDOT, NDOT, and VTrans) reported having formally documented policies that designers can follow to guide their reinforcing bar

selections. Each of these DOTs found this to be a beneficial practice. In addition to formal policies, FDOT has a common practice of creating developmental standards. The advantage of these standards is that they require approval for use, which allows for tracking the use of the standards, the projects using these standards, and the performance of the new innovations that they contain. FDOT views these developmental standards as being advantageous for the continued development of their practices.

Technology Transfer

Technology transfer activities mentioned by the case example participants include routine meetings with suppliers to stay apprised of the latest industry developments (FDOT, MnDOT, NJDOT, and VTrans). VTrans mentioned this as leading to plans to add additional bar types to their specifications and to allow more competition. Most case example participants (FDOT, InDOT, MnDOT, and NJDOT) also engage in technology transfer with designers. A specific example of this is MnDOT’s dissemination of its Service Life Design Guide through internal presentations and through an FHWA peer exchange initiative. FDOT’s website has a page devoted to FRP that also lists numerous technology transfer presentations on these topics, many of which contain the presentation visual aids or full recordings of audio and visual content. FDOT also engages in technology transfer with its contractors, trade associations, and technical societies (e.g., ACI, the American Society of Civil Engineers, Bridge Engineering Institute, and fib) regarding the use of FRP reinforcing bars.

Other Leadership Activities

FDOT also discussed the role of state DOTs in providing investments for testing programs and testing facilities for innovative materials. FDOT is evaluating the potential for internal testing of FRP materials. FDOT is also working to develop a national quality assurance program for FRP materials, in collaboration with AASHTO Product Evaluation & Audit Solutions. These activities are motivated by the goal of decreasing the cost and increasing the use of these materials.

Future Outlook

This section summarizes the case example participants’ future outlook on the use of CRRBs based on their answers to the interview questions “What are your future plans for CRRB?” and “What types of information or resources would be helpful to you with regards to the use of CRRB?” in the following two subsections, respectively.

Future Plans

A common theme in the case example participants’ future plans was continuing to stay open to the uses of new materials that may come into the market or materials not previously used in their DOT, should these options became more cost-effective (FDOT, MnDOT, NJDOT, NDOT, and VTrans). Several participants also expressed openness to revising practices or specifications on the basis of performance that is revealed by new materials or new studies (MnDOT, NJDOT, and VTrans). Specific materials mentioned as being of interest in these discussions included the following:

- Galvanized bars manufactured using continuous galvanizing (MnDOT)

- General FRP, including the goal of an implementation project (NJDOT)

- Basalt FRP, which is anticipated to become more readily available and has recently become standardized in ASTM D8505 (FDOT)

- Mixed CRRBs (e.g., hybrid combinations of stainless steel, GFRP, and CFRP) to optimize designs (FDOT)

Another common theme was new consideration of specific materials. For example, NDOT is currently exploring using crack sealants as overlays as another means to improve durability of rebar. InDOT is evaluating a proprietary low-permeability concrete thought to have more potential for improved durability than alternative bar types. As a result of in-progress research, FDOT also sees an opportunity for reducing conservatism in consideration of creep rupture stress limits for flexural design and in tensile strain limits for shear design when using GFRP and basalt FRP bars.

MnDOT and NJDOT have ongoing initiatives related to data collection and to specification development, respectively. MnDOT is working toward tracking the long-term performance of pilot projects via element-level inspection data; this is anticipated to provide valuable data in the future. NJDOT has three ongoing specification development initiatives. These include updating the NJDOT design manual to include updated CRRB provisions that are under development, participation in an upcoming FHWA workshop on service life design to further their considerations on these topics, and consideration of more stringent specifications on quality control allowances for epoxy-coated reinforcing bars.

Desirable Information

Five of the six case example participants (FDOT, InDOT, NJDOT, MnDOT, and VTrans) highlighted the need for better information on the long-term performance and service life of alternative CRRBs. Three general types of data to inform these needs were specifically mentioned. One of these was the evaluation of existing performance data for different bars (particularly for epoxy-coated and galvanized bars) to better understand the variability in existing data and apply this information to reach conclusions on expected service lives in different environments (NJDOT). Other participants (MnDOT, FDOT, and VTrans) discussed interest in accelerated laboratory testing that simulates different environments to inform relative performance of bar types, with a particular interest in bar types for which there are discrepancies between the current practices of some state DOTs despite similar exposure conditions (MnDOT). The need for such testing specimens to be composed of bars inside of concrete (FDOT and VTrans) and for it to be done by nonprofit entities to provide confidence in the objectivity of results (MnDOT) was emphasized. A third source of information on long-term performance that was discussed was data that can be obtained from existing structures, such as decommissioned bridges (FDOT) and demonstration projects (VTrans) as well as aggregated performance of inventories for states that have implemented policies on selection of CRRBs (VTrans). Although the timescale needed for relevant observations and data on field performance of CRRBs is (ideally) decades, the survey results indicate that such evaluations are at least theoretically possible for specific bridges containing many bar types, particularly those that are coded in the NBI (as discussed in the Benefits section of this chapter). Including cost considerations in such analyses of long-term performance and service life was also noted as being of interest (MnDOT). Each of these types of information contributes to the overarching goal stated by one participant (NJDOT) of progressing this current work summarizing current practices to developing best practices.

Another category of desirable information mentioned was additional guidelines on the use of FRP bars (NJDOT, InDOT, and VTrans). Specific types of information in this category include ideal locations for use, how to design, and considerations for deflection control in decks. VTrans has published guidelines on these topics (as has FDOT); however, VTrans noted that the overhang design when using GFRP is a remaining uncertainty from its perspective.

Other questions were related to the design stresses that should be used for metallic bar types that have higher than typical strengths and the lack of a clearly defined yield point. There were somewhat contradictory views on the design strength of these bar types. MnDOT raised questions regarding how utilizing higher strengths may affect crack widths, particularly in decks (e.g., when using 60%

of the yield stress for service limit states). FDOT speculated that a larger maximum stress could be utilized for stainless steel clad bars than that presently allowed. This is of interest to FDOT in order to make this bar type more competitive with FRP, which is thought to have similar durability but has less familiarity with designers. Stainless steel clad bars are also of interest because this bar type may provide an ideal level of corrosion protection relative to its minimal use of more corrosion-resistant alloying elements (thereby improving cost-effectiveness and environmental impact). Being able to utilize the higher stress capacity of this bar type could further improve its cost-effectiveness. A final topic that was identified was a need for quantitative information on allowable area ratios between anodes and cathodes when using mixed bar designs in different (but connected) structural elements (FDOT).