State DOT Policies and Practices on the Use of Corrosion-Resistant Reinforcing Bars (2025)

Chapter: 5 Summary of Findings

CHAPTER 5

Summary of Findings

Summary of Current Practices

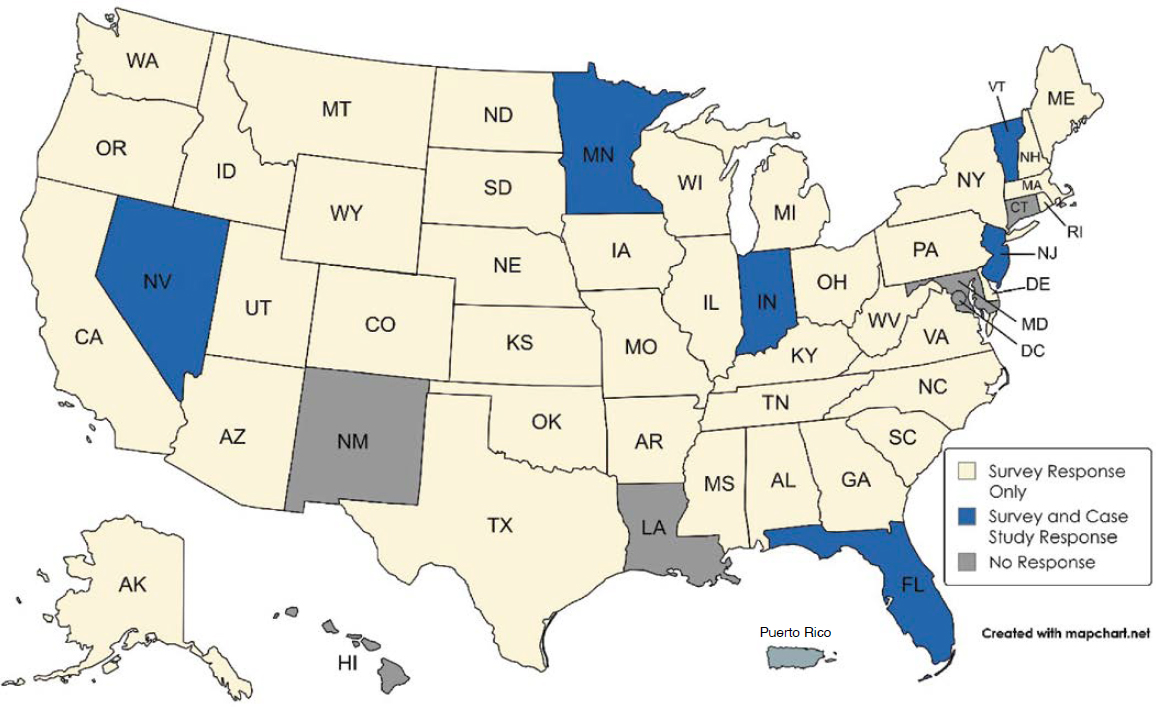

The objective of this synthesis was to document policies and practices used by state DOTs related to the use of CRRBs. Chapter 1 identified specific types of information that were desired to support this goal. The findings related to each of these types of information is summarized in this chapter. All comments regarding survey findings are pertinent to the 45 state DOTs responding to the survey unless noted otherwise, and all generalizations regarding the case examples pertain to the six state DOTs that served as case example participants. These state DOTs are presented by Figure 5-1.

Types of CRRBs Used

Chapter 3 reviewed the types of CRRBs used nationally. Figure 3-2 showed that, of the 45 state DOTs responding to the survey, in present practice most use black or epoxy-coated bars (67% and 73%, or 30 and 33 respondents, respectively); approximately 33% use stainless or galvanized steel (17 and 14 respondents, respectively); approximately 25% use chromium-alloyed or FRP bars (9 and 12 respondents, respectively); and few use steel with multilayer coatings, stainless steel clad, or other bar types (two, zero, and two respondents, respectively). Additional goals of this study were to determine the situations in which each of these bar types are most commonly used in terms of member types, regions of the United States, and time periods. A summary of these findings is given in Table 5-1; region classifications refer to those depicted in Figure 3-9 and are based on the AASHTO regions. Some aspects of the survey asked respondents to distinguish between common use and infrequent use (the sum of which represents “use” in the discussion that follows). The survey also allowed for respondents to indicate more than one bar type as being used or commonly used in each scenario that was queried.

- Black bars. Although all states have used black bars, the number of states doing so dropped by 24% between 1980 (45 respondents) and 2000 (34 respondents) and has continued to slowly decline since then (Figure 3-3). In present practice, black bars are commonly used in the substructure in all regions of the United States (Figure 3-13). Case example participants clarify that uses in substructures in regions where deicing agents are used are often limited to areas away from potentially leaking joints or in buried components with limited oxygen supply. In the superstructures and decks, black bars are used in progressively lesser extents, with black bars only being commonly used in decks in the South and West (Figure 3-12 and Figure 3-11). The case examples reinforce these general trends, with only the representatives from the South and West using black bars as a primary reinforcing bar type in decks, and then only in regions where deicing agents are rarely, if ever, used.

- Epoxy-coated bars. These are commonly used by a majority of the respondents in decks and in superstructures (82% and 64%, or 37 and 29 respondents, respectively; see Figure 3-4).

Table 5-1. Summary of use by bar type.

| Bar Type | Most Typical Use | Regional Variation | Use Trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black | Common use in substructures | Greater use in superstructures and decks in South and West compared to other regions | Declining |

| Epoxy-coated | Common use in superstructures and decks | Less use in South, where black bars have more widespread use | Steady |

| Galvanized | Use in decks | Most commonly used in Northeast | Increasing |

| Steel with multilayer coatings | Use in decks | Only used in Northeast and South | Limited availability |

| Stainless steel | Use in decks | Most commonly used in Northeast; common use limited to decks in West | Increasing |

| Chromium-alloyed steel | Use in decks | Most commonly used in Northeast; common use limited to decks in West | Increasing |

| Stainless steel clad | Use in decks | Not presently or commonly used in any region | Limited availability |

| FRP | Use in decks | Similar frequency of use but variable use applications | Increasing |

- Epoxy-coated bars are commonly used by most (55% to 90%) state DOTs in each region (Figure 3-10). However, two of the six case example participants either do not allow the use of epoxy-coated bars or consider them to have durability similar to that of black bars (Table 4-1). Use of epoxy-coated bars peaked between 1980 and 2000 and has remained steady since 2000 (Figure 3-3).

- Galvanized steel bars. These have the most widespread present use in the Northeast region (six of the nine respondents in that region, or 67%; see Figure 3-10) compared to a maximum of 30% of the respondents in any of the other AASHTO regions. Most of the Northeast state DOTs that use galvanized bars commonly use them in decks (four state DOTs) and half (three state DOTs) commonly use them in superstructures (Figure 3-11 and Figure 3-12). VTrans is one Northeast state DOT that uses galvanized bars; for VTrans these are the primary type of CRRB used. Case example participants in other regions had reservations regarding the performance of these bars. The number of state DOTs using galvanized bars is increasing; it doubled between 2010 and 2023 (Figure 3-3).

- Steel bars with multilayer coatings. These are limited in common use to decks (Figure 3-4) and to current use in the Northeast and South regions (Figure 3-10). Of the case example participants, only VTrans allows this bar type in its specifications, but it is not typically used due to limited availability. None of the survey respondents used this bar type prior to 2010, and only two state DOTs reported commonly using this bar type in new designs (Figure 3-3).

- Stainless steel bars. These do not have widespread common use, but most (25 respondents, or 56%) of state DOTs do use stainless steel bars—at least occasionally—in decks (Figure 3-5). The region in which the greatest proportion of states (22% to 33%) commonly use stainless steel is the Northeast (Figures 3-11, 3-12, and 3-13). Five of the six case example participants (representing three of the four AASHTO regions) use stainless steel in select circumstances that are representative of the most extreme conditions within their states. The number of states using stainless steel has increased significantly since 2010.

- Chromium-alloyed steel bars. These are most typically used in decks (16 respondents; see Figure 3-5), but not commonly (six respondents, or 13%; see Figure 3-4). Use of this bar type is fairly uniform throughout the country, with only two or three state DOTs reporting current use of this bar type in each region of the country (Figure 3-10). The number of states using chromium-alloyed steel has increased significantly since 2010 in terms of nationwide use rates (Figure 3-3). However, none of the case example participants currently use this bar type in the uncoated condition despite its use in isolated cases in three of these six DOTs. MnDOT currently uses this bar type, but only with an epoxy coating.

- Stainless steel clad bars. No state DOT reported commonly using stainless steel clad reinforcing bars in any member type (Figure 3-4), either in the survey or in the case examples. The case example participants related this to cost, availability, lack of familiarity, and concerns regarding breached coatings. However, it was highlighted as a promising alternative to solid stainless steel bars in terms of environmental impact and cost. In none of the time periods that were considered did more than two state DOTs typically use this bar type (Figure 3-3).

- FRP bars. These are typically used in similar proportions in each region of the country (13% to 30%; see Figure 3-10). However, Figures 3-11, 3-12, and 3-13 show that the members in which these bars are commonly used has significant regional variation, with the DOTs in the Northeast and Mid America regions using FRP bars in decks and superstructures, those in the South region using them in superstructures and substructures (where there is little need for them in decks that rarely experience deicing agents), and those in the West region only using FRP bars in decks. From the case examples, some uses of FRP bars include (1) in splash zones in Florida and (2) for use in decks requiring enhanced service life in Minnesota. The number of states using FRP bars has increased significantly since 2010.

Decision-Making Processes

The survey results in Chapter 3 indicate that the member type and the environmental conditions at the bridge location are the primary factors that are considered in specifying reinforcing bar types. All case example participants, as described in Chapter 4 and Table 4-2, consider the member type; most (five of six) consider environmental conditions in specifying reinforcing bar types. Examples of member type considerations include (1) decks treated with deicing agents, (2) substructure elements under joints or in splash zones (because of either marine environments or underpassing roadways), and (3) superstructure components (such as box and segmental girders because of the difficulty of deck replacements in these situations).

Examples of environmental exposure considerations include (1) variations in exposure to deicing agents throughout a given state (based either on geography or on traffic volume) and (2) marine environments. Most case example participants (four of six) also have specific definitions for environmental classifications within their DOTs.

Expected service life of the bridge is also considered by the majority of survey respondents as a primary or secondary factor affecting the choice of CRRB type. Targeting the intended service life is considered inherent to the design process for all case example participants. However, the level of formality and breadth of these considerations varies among these DOTs, with the formality ranging from service life being indirectly considered to being the central design philosophy and the breadth ranging from select signature projects to governing all designs. Recently published AASHTO guide specifications on service life design and an example of how one state has applied this framework to its bridge program are available to support increased use of this concept (AASHTO 2020a; MnDOT 2023).

Other factors considered in choosing reinforcing bar type by one or more case example participants include member locations, member redundancy, location of the bridge relative to the transportation network, and life-cycle cost analysis, with some (2 of 6) case example participants using LCCA in select situations to justify the up-front costs of construction on projects for which a premium was paid for more durable reinforcing bar types. Sample assumptions and considerations for performing LCCA are provided in Chapter 4 in the Synthesis of Decision-Making Criteria section.

Effects on Structural and Concrete Mix Designs

The survey and case example results indicate that the most common modification made to other aspects of design when using CRRBs is the alternative strength properties of some CRRB types. However, this is not particularly common; only 18% of survey respondents (8 of 45) make such considerations. Half of the case example participants have leveraged the additional strength of stainless and chromium-alloyed steel bars to reduce the number of bars or overall area of reinforcement. Design guidelines that exist for using FRP bars are described in Chapter 4 in the Modifications Based on Material Properties of Bars section.

It was found that concrete mix designs are rarely varied (36 of 44 respondents, or 82%), but when they are, concrete permeability is the factor most commonly considered (4 of 44 respondents, or 9%). Sample specifications for this are reported in Chapter 4. It was also found that relatively high cover distances are typically used in conjunction with CRRB types. This applies to bar types that both are and are not explicitly addressed in the AASHTO LRFD BDS. The survey results indicated that the cover distances used for bar types that are not explicitly identified in the AASHTO LRFD BDS are relatively high (Figure 3-26). The case examples demonstrate instances in which DOTs have applied more conservative cover distances than the minimums specified in the AASHTO LRFD BDS.

Quality Control Considerations

Of the survey respondents, (21 of 44, or 48%) require additional or alternative quality control methods for CRRB; 8 of 44 (18%) indicated that they have considered such requirements. Examples of quality control considerations from the case examples include those in Section 9 (Reinforcing Steel) of the AASHTO LRFD Bridge Construction Specifications (AASHTO 2020c), which includes material specifications (via reference to relevant ASTM and AASHTO specifications) as well as quality control issues during fabrication (such as bending) and construction (including handling, on-site storing, and surface condition). Several case example participants (4 of 6) have more stringent or alternative specifications on the damage tolerances and repair requirements for epoxy-coated bars relative to the AASHTO specifications. Other procedures specific to one or more case example participants include consideration of the cut ends of coated bars, development and maintenance of qualified product or supplier lists, creation of special provisions when implementing new types of CRRBs, and site considerations (such as physically separating alternative bar types on construction sites).

Uncertainties, Limitations, and Challenges

This study considered potential impediments to the successful use of CRRBs from three perspectives. Uncertainties were defined as structural and corrosion performance metrics for which uncertainties have limited the use of specific types CRRBs. Most survey respondents (24 of 45, or 53%) indicated uncertainties for FRP bars; structural performance, fatigue performance, durability, and other unspecified concerns each received similar numbers of responses. Approximately one-third of respondents indicated uncertainties for all other bar types (13 to 16 of 45, or 29% to 36% depending on the bar type; see Figure 3-32) except for stainless steel and other unspecified bar types. Corrosion performance was the most common uncertainty for all of these bar types (8 to 11 of 45 respondents, or 18% to 24%) except for stainless steel clad and FRP bars, for which other unspecified concerns was the most common answer (9 of 45 respondents, or 20%) and was tied with structural performance concerns for FRP bars.

Limitations were defined as practical constraints that limit CRRB use. Epoxy-coated bars were the only bar type for which most respondents (31 of 45, or 69%) indicated no limitations. Stainless steel bars had the highest frequency of limitations (40 of 45 respondents, or 89%). Cost was indicated as the most common limitation of stainless steel bars (37 of 45 respondents, or 82%), followed by availability (10 of 45 respondents, or 22%). Case example participants discussed experiencing some, but limited, challenges with material availability as a result of global supply chain issues. Familiarity of designers and owners was also a relatively common answer for most bar types. Case example participants elaborated that this was particularly the case for FRP bars and higher-strength metallic bars, for which design practices differ or may differ, respectively.

Challenges were defined as problems that have been encountered at the stage of field implementation of CRRBs or later. A slight majority of survey respondents indicated not experiencing such challenges. The most common challenges that were specified in the survey were that the specified material was not available (8 of 45 respondents, or 18%). Case example participants have also experienced challenges related to field modifications to plans, which cause lead time issues for coated bars. Other disadvantages for specific bar types were presented in Table 2-2.

Benefits

Conceptual advantages of specific bar types were reported in Table 2-2. Actual benefits of the collective use of CRRBs were reported by 34 of 45 survey respondents (76%). All of these respondents reported improved durability of decks, consistent with conceptual expectations. Durability of

other components was also reported by the majority of respondents. All case example participants reported similar findings. Examples cited included improved deck durability; fewer repairs; performance and periodic monitoring observations of demonstration projects using FRP, stainless steel, and chromium-alloyed steel bars; and lack of spalling on reinforced concrete members containing CRRBs. Case example participants also discussed secondary benefits that arise from improved durability. Examples of this included less maintenance and fewer road closures and consequently reduced environmental impact and reduced life-cycle cost, which were indicated by 7% and 49% of survey respondents, respectively.

Although all case example participants had quantified information available on CRRB benefits, none had formally documented these findings. However, it was noted by NJDOT that the reinforcing type is often recorded in the NBI, so there is potential for this to be quantitatively evaluated in the future. Furthermore, FDOT has quantified the rehabilitation cost of providing galvanic jackets to piers that did not contain CRRBs at $100M, which is an expense that could potentially be avoided by using CRRBs.

Implementation Efforts

The survey indicated that 43 of the 45 respondents (96%) had engaged in some form of implementation activity regarding CRRBs. Demonstration or pilot projects were the most common example of this (33 of 45 respondents, or 73%; see Figure 3-37). Examples of this from the case examples include projects using FRP and stainless steel.

Also on this topic, MnDOT is developing a feature for their bridge inspection program that will track the unique features of pilot projects in the future via element-level inspection items. This could greatly improve the ability to track the performance of new technologies as they are implemented. At the time of this synthesis, no quantitative information to assess the relative success or effectiveness of these or other implementation efforts was readily available.

Other common implementation efforts include research and liaising with fabricators and suppliers. Examples of these activities from the case examples include research on the comparative corrosion performance of various types of CRRBs, which led to state specifications. Technology transfer activities mentioned by the case example participants included routine meetings with suppliers to stay apprised of the latest industry developments.

Written Policies Governing the Application of CRRBs

In response to the survey, 25 of the 45 respondents indicated that they had documentation or tools governing the choice of CRRBs and associated design provisions. Twenty of these state DOTs provided links to this information, which can be found in Table C-51 of Appendix C, along with notes on the sections of these documents pertaining to CRRBs as provided by the respondents. Chapter 4 summarizes the policies and practices relating to CRRBs in the state DOTs represented by the case examples. These demonstrate a considerable range in approaches in terms of the number and types of CRRB options considered, the number and types of factors considered in choosing among CRRB types (e.g., variable environments or service lives), and the flexibility of the approaches in making a final determination of CRRB type.

Summary of Knowledge Gaps and Suggested Research

The need for better information on the long-term performance and service life of alternative CRRBs was a common theme among types of information desirable to the case example participants in the concluding section of Chapter 4. This is particularly relevant, as service life design is a

design philosophy that is becoming increasingly formalized. It is desirable that discrepancies among the current practices of some state DOTs (despite them having similar exposure conditions) be resolved. A notable example of this is epoxy-coated bars, as they are commonly used by a majority of the survey respondents in all regions of the country and in most member types, yet some state DOTs consider them to have low durability. These opposing viewpoints can each be supported by literature, depending upon whether performance is normalized relative to the small areas of damaged epoxy considered in prior testing (which results in poor performance expectations in these localized areas) or normalized relative to the total bar area (which results in good performance expectations on average). To assess which of these philosophies is most appropriate, more information on the long-term performance of repairs to damaged coating areas would be valuable.

Related to the general theme of better understanding service life, current estimates based on scientific principles are typically based on a summation of (1) time to corrosion initiation, (2) time from corrosion initiation to cracking, and (3) time from cracking until repair is needed. There is variability in the quality and quantity of the information for these three phases as well as for different bar types. For some bar types, there are reasonably sized datasets on chloride thresholds for corrosion initiation and corrosion rates, but larger scientific gaps exist regarding the amount of section loss that initiates concrete cracking and the propagation of cracking to a point of severity at which repair is needed. In addition, current service life estimates are generally calibrated based on relatively limited field observations in selected environments. Considerations of additional practical situations would be informative. This information would improve service life estimates of reinforced concrete components and therefore have direct practical value. An additional scientific topic that was identified as a type of information needed was quantitative information on allowable area ratios between anodes and cathodes when using mixed bar designs in different but connected structural elements.

Linking service life estimates based on scientific principles to field observations provides needed fundamental understanding that is combined with realistic information. The dataset compiled in this synthesis may have the potential to inform such work. For example, this data can be readily leveraged to identify state DOTs that have used certain types of CRRB over various timeframes. Those that have used various CRRB types for the longest timeframes would likely provide the most relevant data. However, applicability of such applications of CRRBs should also be considered relative to present best practices. Current data can also be used to prioritize various bar types based on frequency of present use and interest in future use. Relevant efforts could include data mining from populations of bridges currently using CRRBs in order to aggregate existing semi-qualitative data (such as condition ratings) and more quantitative data (in the form of the percentages of various elements in different element-level condition states). To the extent possible, meaningful analysis of such data would include consideration of differences in environmental exposures (including marine environments and variability in quantity and types of deicing agents), design practices, and maintenance practices. A well-designed long-term monitoring program for selected field bridges would also provide valuable information. Opportunities also exist for leveraging data from decommissioned bridges and demonstration projects.

The prevalence of reinforced concrete bridge decks as a common element to nearly all structures in all environments provides both a large real-world dataset to inform such questions and high motivation for such research as a wise economical investment. Research on other member types is also of interest. The current state of knowledge is at a level of maturity where the influential variables are largely known, but their full range of effects and interactions are not; this further increases the likelihood that such research would be impactful by generating information of sufficient maturity to have practical applications in relatively short timescales.

The lack of high-quality information on CRRB service lives in a range of realistic environments also creates knowledge gaps in the data needed to perform reliable LCCA, and therefore

complicates decision-making processes. Similarly, the importance of having more data on maintenance costs was mentioned as desirable for improving LCCA and associated decision-making. This is an additional knowledge gap for which the present dataset can be leveraged—in this case to strategically identify state DOTs that would be ideal sources of such cost information based on the timeframe in which they have used various types of CRRBs.

A final durability knowledge gap related to the implementation of CRRBs is uncertainty regarding best practices for concrete mix design to be used in conjunction with various types of CRRBs. A specific area of interest is to compile best practices and explore additional opportunities to reduce cracking in concrete members, which will in turn result in better performance for CRRBs that are vulnerable to water and salt ingress through cracks in concrete. More information on optimal mix design is also needed so that bridge durability is not limited by concrete performance, as the determination and implementation of best practices for CRRBs will likely extend the lifespan of the reinforcing bars.

Although the implementation of CRRBs is typically motivated by durability goals, some types of CRRBs are not necessarily a direct replacement for traditional black bars because of their alternative mechanical properties. Three of the six case example participants highlighted a need for additional guidelines on the use of FRP bars, because the fundamental behavior of designs using these bars differs from the behavior of concrete members that are reinforced with metallic bars. Ideal practices for performing demolition and repairs or reconstruction (including deck widening) of members with FRP reinforcing bars are an additional knowledge gap for this bar type. FRP bars also do not exhibit visible signs of degradation, making the inspection and repair of FRP-reinforced structures more challenging, since traditional assessment and repair methods may be inadequate.

Some metallic bars have higher than typical strengths and lack a clearly defined yield point. There is no consensus on the ideal stress capacity that should be assumed for these bars for service and strength-limit states. These uncertainties have implications for deflection control (due to the potential use of fewer lower modulus bars) and crack width control (due to the potential for greater tensile stresses). The applicability of empirical deck design to these bar types is also questioned.

A final knowledge gap for CRRBs is that current AASHTO LRFD BDS specifications (AASHTO 2020a) only consider development lengths for black and epoxy-coated bars. The AASHTO Guide Specifications for GFRP Reinforced Concrete (AASHTO 2018) recommends development lengths for this bar type. Limited research has been performed on development length of other bar types. Research on statistically significant sample sizes with considerations of more variables than considered in prior research could allow development lengths for more CRRB types to become codified.