Learning from Our Buildings: A State-of-the-Practice Summary of Post-Occupancy Evaluation (2001)

Chapter: 2 The Evolution of Post-Occupancy Evaluation: Toward Building Performance and Universal Design Evaluation

2

The Evolution of Post-Occupancy Evaluation: Toward Building Performance and Universal Design Evaluation

Wolfgang F.E. Preiser, Ph.D., University of Cincinnati

The purpose of this chapter is to define and provide a rationale for the existence of building performance evaluation. Its history and evolution from post-occupancy evaluation over the past 30 years is highlighted. Major methods used in performance evaluations are presented and the estimated cost and benefits described. Training, opportunities and approaches for building performance evaluation are enumerated. Possible opportunities for government involvement in building performance evaluation are sketched out. The next step and new paradigm of universal design evaluation is outlined. Last but not least, questions and issues regarding the future of building performance evaluation are raised.

POST-OCCUPANCY EVALUATION: AN OVERVIEW

A definition of post-occupancy evaluation was offered by Preiser et al. (1988): post-occupancy evaluation (POE) is the process of evaluating buildings in a systematic and rigorous manner after they have been built and occupied for some time. The history of POE was also described in that publication and was summarized by Preiser (1999), starting with one-off case study evaluations in the late 1960s and progressing to systemwide and cross-sectional evaluation efforts in the 1970s and 1980s. While these evaluations focused primarily on the performance of buildings, the latest step in the evolution of POE toward building performance evaluation (BPE) and universal design evaluation (UDE) is one that emphasizes a holistic, process-oriented approach to evaluation. This means that not only facilities, but also the forces that shape them (political, economic, social, etc.), are taken into account. An example of such process-oriented evaluations was the development of the Activation Process Model and Guide for hospitals of the Veterans Administration (Preiser, 1997). In the future, one can expect more process-oriented evaluations to occur, especially in large government and private sector organizations, which operate in entire countries or globally, respectively.

Many actors participate in the use of buildings, including investors, owners, operators, maintenance staff, and perhaps most important of all, the end users (i.e., actual persons occupying the building). The focus of this chapter is on occupants and their needs as they are affected by building performance and on occupant evaluations of buildings. The term evaluation contains the world “value”; thus, occupant evaluations must state explicitly whose values are referred to in a given case. An evaluation must also state whose values are used as the context within which performance will be tested. A meaningful evaluation focuses on the values behind the goals and objectives of those who wish their buildings to be evaluated, in addition to those who carry out the evaluation.

There are differences between the quantitative and qualitative aspects of building performance and the respective performance measures. Many aspects of building performance are in fact quantifiable, such as lighting, acoustics, temperature and humidity, durability of materials, amount and distribution of space, and so on. Qualitative aspects of building performance pertain to the ambiance of a space (i.e., the appeal to the sensory modes of touching, hearing, smelling, and kinesthetic and visual perception, including color). Furthermore, the evaluation of qualitative aspects of building performance, such as aesthetic beauty or visual

compatibility with a building’s surroundings, is somewhat more difficult and subjective and less reliable. In other cases, the expert evaluator will pass judgment. Examples are the expert ratings of scenic and architectural beauty awarded chateaux along the Loire River in France, as listed in travel guides. The higher the apparent architectural quality and interest of a building, the more stars it will receive. Recent advances in the assessment methodology for visual aesthetic quality of scenic attractiveness are encouraging. It is hoped that someday it will be possible to treat even this elusive domain in a more objective and quantifiable manner (Nasar, 1988).

POE is not the end phase of a building project; rather, it is an integral part of the entire building delivery process. It is also part of a process in which a POE expert draws on available knowledge, techniques, and instruments in order to predict a building’s likely performance over a period of time.

At the most fundamental level, the purpose of a building is to provide shelter for activities that could not be carried out as effectively, or carried out at all, in the natural environment. A building’s performance is its ability to accomplish this. POE is the process of the actual evaluation of a building’s performance once in use by human occupants.

A POE necessarily takes into account the owners’, operators’, and occupants’ needs, perceptions, and expectations. From this perspective, a building’s performance indicates how well it works to satisfy the client organization’s goals and objectives, as well as the needs of the individuals in that organization. A POE can answer, among others, these questions:

-

Does the facility support or inhibit the ability of the institution to carry out its mission?

-

Are the materials selected safe (at least from a short-term perspective) and appropriate to the use of the building?

-

In the case of a new facility, does the building achieve the intent of the program that guided its design?

TYPES OF EVALUATION FOR BUILDING PROJECTS

Several types of evaluation are made during the planning, programming, design, construction, and occupancy phases of a building project. They are often technical evaluations related to questions about the materials, engineering, or construction of a facility. Examples of these evaluations include structural tests, reviews of load-bearing elements, soil testing, and mechanical systems performance checks, as well as post-construction evaluation (physical inspection) prior to building occupancy.

Technical tests usually evaluate some physical system against relevant engineering or performance criteria. Although technical tests indirectly address such criteria by providing a better and safer building, they do not evaluate it from the point of view of occupant needs and goals or performance and functionality as they relate to occupancy. The client may have a technologically superior building, but it may provide a dysfunctional environment for people.

Other types of evaluations are conducted that address issues related to operation and management of a facility. Examples are energy audits, maintenance and operation reviews, security inspections, and programs that have been developed by professional facility managers. Although they are not POEs, these evaluations are relevant to questions similar to those described above.

The process of POE differs from these and technical evaluations in several ways:

-

A POE addresses questions related to the needs, activities, and goals of the people and organization using a facility, including maintenance, building operations, and design-related questions. Other tests assess the building and its operation, regardless of its occupants.

-

The performance criteria established for POEs are based on the stated design intent and criteria contained in or inferred from a functional program. POE evaluation criteria may include, but are not solely based on, technical performance specifications.

-

Measures used in POEs include indices related to organizational and occupant performance, such as worker satisfaction and productivity, as well as measures of building performance referred to above (e.g., acoustic and lighting levels, adequacy of space and spatial relationships).

-

POEs are usually “softer” than most technical evaluations. POEs often involve assessing psychological needs, attitudes, organizational goals and changes, and human perceptions.

-

POEs measure both successes and failures inherent in building performance.

PURPOSES OF POEs

A POE can serve several purposes, depending on a client organization’s goals and objectives. POE can provide the necessary data for the following:

-

To measure the functionality and appropriateness of design and to establish conformance with performance requirements as stated in the functional program. A facility represents policies, actions, and expenditures that call for evaluation. When POE is used to evaluate design, the evaluation must be based on explicit and comprehensive performance requirements contained in the functional program statement referred to above.

-

To fine-tune a facility. Some facilities incorporate the concept of “adaptability,” such as office buildings, where changes are frequently necessary. In that case, routinely recurring evaluations contribute to an ongoing process of adapting the facility to changing organizational needs.

-

To adjust programs for repetitive facilities. Some organizations build what is essentially the identical facility on a recurring basis. POE identifies evolutionary improvements in programming and design criteria, and it also tests the validity of underlying premises that justify a repetitive design solution.

-

To research effects of buildings on their occupants. Architects, designers, environment-behavior researchers, and facility managers can benefit from a better understanding of building-occupant interactions. This requires more rigorous scientific methods than design practitioners are normally able to use. POE research in this case involves thorough and precise measures and more sophisticated levels of data analysis, including factor analysis and cross-sectional studies for greater generalizability of findings.

-

To test the application of new concepts. Innovation involves risk. Tried-and-true concepts and ideas can lead to good practice, and new ideas are necessary to make advances. POE can help determine how well a new concept works once applied.

-

To justify actions and expenditures. Organizations have greater demands for accountability, and POE helps generate the information to accomplish this objective.

TYPES OF POEs

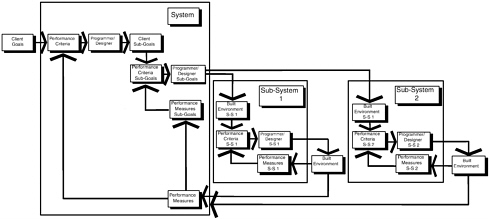

Depicted in Figure 2-1 is an evolving POE process model showing three levels of effort that can be part of a typical POE, as well as the three phases and nine steps that are involved in the process of conducting POEs:

-

Indicative POEs give an indication of major strengths and weaknesses of a particular building’s performance. They usually consist of selected interviews with knowledgeable informants, as well as a subsequent walk-through of the facility. The typical outcome is awareness of issues in building performance.

-

Investigative POEs go into more depth. Objective evaluation criteria either are explicitly stated in the functional program of a facility or have to be compiled from guidelines, performance standards, and published literature on a given building type. The outcome is a thorough understanding of the causes and effects of issues in building performance.

-

Diagnostic POEs correlate physical environmental measures with subjective occupant response measures. Case study examples of POEs at these three levels of effort can be found in Preiser et al. (1988). The outcome is usually the creation of new knowledge about aspects of building performance.

The three phases of the post-occupancy evaluation process model are (1) planning, (2) conducting, and (3) applying. The planning phase is intended to prepare the POE project, and it has three steps: (1) reconnaissance and feasibility, (2) resource planning, and (3) research planning. In this phase, the parameters for the POE project are established; the schedule, costs, and manpower needs are determined; and plans for data collection procedures, times, and amounts are laid out.

Phase 2—conducting—consists of (4) initiating the on-site data collection process, (5) monitoring and managing data collection procedures, and (6) analyzing data. This phase deals with field data collection and methods of ensuring that preestablished sampling procedures and data are actually collected in a manner that is commensurate with the POE goals.

Furthermore, data are analyzed in preparation for the final phase—applying. This phase contains steps (7) reporting findings, (8) recommending actions, and

FIGURE 2-1 Post-occupancy evaluation: evolving performance criteria.

finally, (9) reviewing outcomes. Obviously, this is the most critical phase from a client perspective, because solutions to identified problems are outlined and recommendations are made for actions to be taken. Furthermore, monitoring the outcome of recommended actions is a significant step, since the benefits and value of POEs are established in this final step of the applying phase.

Critical in Figure 2-1 is the arrow that points to “feedforward” into the next building cycle. Clearly, one of the best applications of POE is its use as input into the pre-design phases of the building delivery cycle (i.e., needs analysis or strategic planning and facility programming).

BENEFITS, USES, AND COSTS OF POEs

Each of the above types of POEs can result in several benefits and uses. Recommendations can be brought back to the client, and remodeling can be done to correct problems. Lessons learned can influence design criteria for future buildings, as well as provide information to the building industry about buildings in use. This is especially relevant to the public sector, which designs buildings for its own use on a repetitive basis.

The many uses and benefits—short, medium, and long term—that result from conducting POEs are listed below. They refer to immediate action, the three- to five-year intermediate time frame, which is necessary for the development of new construction projects, and the long-term time frame ranging from 10 to 25 years, which is necessary for strategic planning, budgeting, and master planning of facilities. These benefits provide the motivation and rationale for committing to POE as a concept and for developing POE programs.

Short-term benefits include the following:

-

identification of and solutions to problems in facilities,

-

proactive facility management responsive to building user values,

-

improved space utilization and feedback on building performance,

-

improved attitude of building occupants through active involvement in the evaluation process,

-

understanding of the performance implications of

-

changes dictated by budget cuts, and

-

better-informed design decision-making and understanding of the consequences of design.

Medium-term benefits include the following:

-

built-in capacity for facility adaptation to organizational change and growth over time, including recycling of facilities into new uses,

-

significant cost savings in the building process and throughout the life cycle of a building, and

-

accountability for building performance by design professionals and owners.

Long-term benefits include the following:

-

long-term improvements in building performance,

-

improvement of design databases, standards, criteria, and guidance literature, and

-

improved measurement of building performance through quantification.

The most important benefit of a POE is its positive influence upon the delivery of humane and appropriate environments for people through improvements in the programming and planning of buildings. POE is a form of product research that helps designers develop a better design in order to support changing requirements of individuals and organizations alike.

POE provides the means to monitor and maintain a good fit between facilities and organizations, and the people and activities that they support. POE can also be used as an integral part of a proactive facilities management program.

Based on the author’s experience in conducting POEs at different levels of effort (indicative, investigative, and diagnostic) and involving different levels of sophistication and manpower, the estimated cost of these POEs ranges from 50 cents a square foot for indicative-type POEs to anywhere from $2.50 upward at the diagnostic level. Some diagnostic-type POEs have cost hundreds of thousands of dollars; such as those commissioned by the U.S. Postal Service (Farbstein et al., 1989). On the other hand, indicative POEs, if carried out by experienced POE consultants, can cost as little as a few thousand dollars per facility and can be concluded within a matter of a few days, involving only a few hours of walk-through activity on site.

The range of charges for investigative-type POEs, according to the author’s experience, is between $15,000 and $20,000 and covers just about that many square feet (Preiser and Stroppel, 1996; Preiser, 1998), amounting to approximately $1.00 per square foot evaluated.

The three-day POE workshop format developed by the author typically costs around $5,000, plus expenses for travel and accommodation (Preiser, 1996), and it has proven to be a valuable training and fact-finding approach for clients’ staff and facility personnel.

AN INTEGRATIVE FRAMEWORK FOR BUILDING PERFORMANCE EVALUATIONS

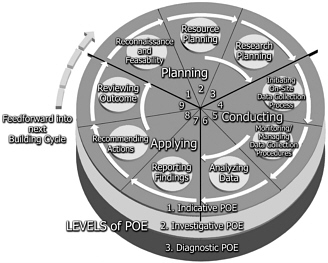

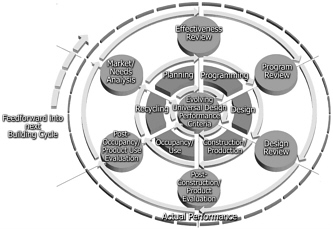

In 1997, the POE process model was developed into an integrative framework for building performance evaluation (Preiser and Schramm, 1997), involving the six major phases of the building delivery and life cycles (i.e., planning, programming, design, construction, occupancy, and recycling of facilities). In the following material, the integrative framework for building performance evaluation is outlined. The time dimension was the major added feature, plus internal review or troubleshooting and testing cycles in each of the six phases.

The integrative framework shown in Figure 2-2 attempts to respect the complex nature of performance evaluation in the building delivery cycle, as well as the life cycle of buildings. This framework defines the building delivery cycle from an architect’s perspective, showing its cyclic evolution and refinement toward a moving target of achieving better building performance overall and better quality as perceived by the building occupants.

At the center of the model is actual building performance, both measured quantitatively and experienced qualitatively. It represents the outcome of the building delivery cycle, as well as building performance during its life cycle. It also shows the six subphases referred to above: planning, programming, design, construction, occupancy, and recycling. Each of these phases has internal reviews and feedback loops. Furthermore, each phase is connected with its respective state-of-the-art knowledge contained in building type-specific databases, as well as global knowledge and the literature in general. The phases and feedback loops of the framework can be characterized as follows:

-

Phase 1—Planning: The beginning of the building delivery cycle is the strategic plan which

FIGURE 2-2 Building performance evaluation: integrative framework for building delivery and life cycle.

-

establishes medium- and long-term needs of an organization through market or needs analysis, which in turn is based on mission and goals, as well as facility audits. Audits match needed items, including space, with existing resources in order to establish actual demand.

-

Loop 1—Effectiveness Review: Outcomes of strategic planning are reviewed in relation to big-issue categories, such as corporate symbolism and image, visibility in the context surrounding the site, innovative technology, flexibility and adaptive re-use, initial capital cost, operating and maintenance cost, and costs of replacement and recycling at the end of the useful life of a building.

-

Phase 2—Programming: Once effectiveness review, cost estimating, and budgeting have occurred, a project has become a reality and programming can begin.

-

Loop 2—Program Review: The outcome of this phase is marked by a comprehensive documentation of the program review involving the client, the programmer, and representatives of the actual occupant groups.

-

Phase 3—Design: This phase contains the steps of schematic design, design development, and working drawings or construction documents.

-

Loop 3—Design Review: The design phase has evaluative loops in the form of design review or troubleshooting involving the architect, the programmer, and representatives of the client organization. The development of knowledge-based and computer-aided design (CAD) techniques makes it possible to apply evaluations during the earliest design phases. This allows designers to consider the effects of design decisions from various perspectives, while it is not too late to make modifications in the design.

-

Phase 4—Construction: In this phase, construction managers and architects share in construction administration and quality control to ensure contractual compliance.

-

Loop 4—Post-Construction Evaluation: The end of the construction phase is marked by post-construction evaluation, an inspection that results in “punch lists,” that is, items that need to be completed prior to commissioning and acceptance of the building by the client.

-

Phase 5—Occupancy: During this phase, move-in and start-up of the facility occur, as well as fine-tuning by adjusting the facility and its occupants to achieve optimal functioning.

-

Loop 5—POE: Building performance evaluation

-

during this phase occurs in the form of POEs carried out six to twelve months after occupancy, thereby providing feedback on what works in the facility and what does not. POEs will assist in testing hypotheses made in prototype programs and designs for new building types, for which no precedents exist. Alternatively, they can be used to identify issues and problems in the performance of occupied buildings and further suggest ways to solve these. Furthermore, POEs are ideally carried out in regular intervals, that is, in two- to five-year cycles, especially in organizations with recurring building programs.

-

Phase 6—Recycling: On the one hand, recycling of buildings to similar or different uses has become quite common. Lofts have been converted to artist studios and apartments; railway stations have been transformed into museums of various kinds; office buildings have been turned into hotels; and factory space has been remodeled into offices or educational facilities. On the other hand, this phase might constitute the end of the useful life of a building when the building is decommissioned and removed from the site. In cases where construction and demolition waste reduction practices are in place, building materials with the potential for re-use will be sorted and recycled into new products. At this point, hazardous materials, such as chemicals and radioactive waste, are removed in order to reconstitute the site for new purposes.

UNIVERSAL DESIGN EVALUATION

The concept, framework, and evolution of universal design evaluation are based on consumer feedback-driven, preexisting, evolutionary evaluation process models developed by the author (i.e., POE and BPE). The intent of UDE is to evaluate the impact on the user of universally designed environments. Working with Mace’s definition of universal design, “an approach to creating environments and products that are usable by all people to the greatest extent possible” (Mace, 1991, in Preiser, 1991), protocols are needed to evaluate the outcomes of this approach. Possible strategies for evaluation in the global context are presented, along with examples of case study evaluations that are presently being carried out. Initiatives to introduce universal design evaluation techniques in education and training programs are outlined. Exposure of students in the design disciplines to philosophical, conceptual, methodological, and practical considerations of universal design is advocated as the new paradigm for “design of the future.”

UNIVERSAL DESIGN PERFORMANCE

The goal of universal design is to achieve universal design performance of designs ranging from products and occupied buildings to transportation infrastructure and information technology that are perceived to support or impede individual, communal, or organizational goals and activities. Since this chapter was commissioned by the Federal Facilities Council, the remainder of the discussion will focus on buildings and the built environment as far as universal design is concerned.

A philosophical base and a set of objectives are the seven principles of Universal Design (Center for Universal Design, 1997).

-

They define the degree of fit between individuals or groups and their environment, both natural and built.

-

They refer to the attributes of products or environments that are perceived to support or impede human activity.

-

They imply the objective of minimizing adverse effects of products, environments, and their users, such as discomfort, stress, distraction, inefficiency, and sickness, as well as injury and death through accidents, radiation, toxic substances, and so forth.

-

They constitute not an absolute, but a relative, concept, subject to different interpretations in different cultures and economies, as well as temporal and social contexts. Thus, they may be perceived differently over time by those who interact with the same facility or building, such as occupants, management, maintenance personnel, and visitors.

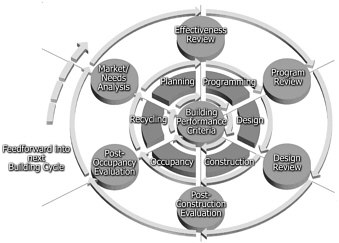

The nature of basic feedback systems was discussed by von Foerster (1985): The evaluator makes comparisons between the outcomes (O) which are actually sensed or experienced, and the expressed goals (G) and expected performance criteria (C), which are usually documented in the functional program and made explicit through performance specifications. Von Foerster observed that “even the most elementary models of the signal flow in cybernetic systems require a (motor) interpretation of a (sensory) signal” and, fur-

ther, “the intellectual revolution brought about by cybernetics was simply to add to a ‘machine,’ which was essentially a motoric power system or a sensor that can ‘see’ what the machine or organism is doing, and, if necessary, initiate corrections of its actions when going astray.” The evolutionary feedback process in building delivery in the future is shown in Figure 2-3. The motor driving such a system is the programmer, designer, or evaluator who is charged with the responsibility of ensuring that buildings meet state-of-the-art performance criteria.

The environmental design and building delivery process is goal oriented. It can be represented by a basic system model with the ultimate goal of achieving universal design performance criteria:

-

The universal design performance framework conceptually links the overall client goals (G), namely those of achieving environmental quality, with the elements in the system that are described in the following items.

-

Performance evaluation criteria (C) are derived from the client’s goals (G), standards, and state-of-the-art criteria for a building type. Universal design performance is tested or evaluated against these criteria by comparing them with the actual performance (P) (see item 5 below).

-

The evaluator (E) moves the system and refers to such activities as planning, programming, designing, constructing, activating, occupying, and evaluating an environment or building.

-

The outcome (O) represents the objective, physically measurable characteristics of the environment or building under evaluation (e.g., its physical dimensions, lighting levels, and thermal performance).

-

The actual performance (P) refers to the performance as observed, measured, and perceived by those occupying or assessing an environment, including the subjective responses of occupants and objective measures of the environment.

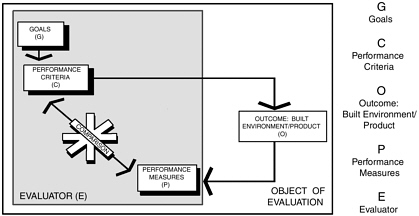

Any number of subgoals (Gs) for achieving environmental quality can be related to the basic system (Preiser, 1991) through modified evaluators (Es), outcomes (Os), and performance (Ps). Thereby, the outcome becomes the subgoal (Gs) of the subsystem with respective criteria (Cs), evaluators (Es), and performance of the subsystem (Ps). The total outcome of the combined basic and subsystems is then perceived (P) and assessed (C) as in the basic system (in Figure 2-4).

PERFORMANCE LEVELS

Subgoals of building performance may be structured into three performance levels pertaining to user needs:

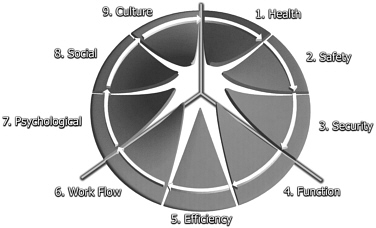

FIGURE 2-3 Performance concept/evaluation system.

the health-safety-security level, the function and efficiency level, and the psychological comfort and satisfaction level. With reference to these levels, a subgoal might include safety; adequate space and spatial relationships of functionally related areas; privacy, sensory stimulation, or aesthetic appeal. For a number of subgoals, performance levels interact and may also conflict with each other, requiring resolution.

Framework elements include products-buildings-settings, building occupants and their needs. The physical environment is dealt with on a setting-by-setting basis. Framework elements are considered in groupings from smaller to larger scales or numbers or from lower to higher levels of abstraction, respectively.

For each setting and occupant group, respective performance levels of pertinent sensory environments and quality performance criteria are required (e.g., for the acoustic, luminous, gustatory, olfactory, visual, tactile, thermal, and gravitational environments). Also relevant is the effect of radiation on the health and well-being of people, from both short- and long-term perspectives.

As indicated above, occupant needs versus the built environment or products are construed as performance levels. Grossly analogous to the human needs hierarchy (Maslow, 1948) of self-actualization, love, esteem, safety, and physiological needs, a three-level breakdown of performance levels reflects occupant needs in the physical environment. This breakdown also parallels three basic levels of performance requirements for buildings (i.e., firmness, commodity, delight), which the Roman architect Vitruvius (1960) had pronounced.

These historic constructs, which order occupant needs, were transformed and synthesized into the “habitability framework” (Preiser, 1983) by devising three levels of priority depicted in Figure 2-5:

-

health, safety, and security performance;

-

functional, efficiency, and work flow performance; and

-

psychological, social, cultural, and aesthetic performance.

These three categories parallel the levels of standards and guidance designers should or can avail themselves of. Level 1 pertains to building codes and life safety standards projects must comply with. Level 2 refers to the state-of-the-art knowledge about products, building types, and so forth, exemplified by agency-specific design guides or reference works such as Time-Saver Standards: Architectural Design Data (Watson et al., 1997). Level 3 pertains to research-based design guidelines, which are less codified but nevertheless of importance for building designers and occupants alike.

The relationships and correspondences between the

FIGURE 2-5 Evolving performance criteria.

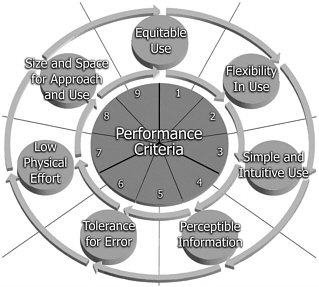

habitability framework and the principles of universal design devised by the Center for Universal Design (1997) are shown in Figure 2-6.

In summary, the framework presented here systematically relates buildings and settings to building occupants and their respective needs vis à vis the product or the environment. It represents a conceptual, process-oriented approach that accommodates relational concepts to applications in any type of building or environment. This framework can be transformed to permit stepwise handling of information concerning person-environment relationships (e.g., in the programming specification, design, and hardware selection for acoustic privacy).

TOWARD UNIVERSAL DESIGN EVALUATION

The book Building Evaluation Techniques (Baird et al., 1996) showcased a variety of building evaluation techniques, many of which would lend themselves to adaptation for purposes of UDE. In that same volume, this author (Preiser, 1996) presented a chapter on a three-day POE training workshop and prototype testing module, which involved both the facility planners and designers and the building occupants (after one year of occupancy), a formula that has proven to be very effective in generating useful performance feedback data. A proposed UDE process model is shown in Figure 2-7.

Major benefits and uses are well known and include, when applied to UDE, the following:

-

Identify problems and develop universal design solutions.

-

Learn about the impact of practice on universal design and on building occupants in general.

-

Develop guidelines for enhanced universal design concepts and features in buildings, urban infrastructure, and systems.

-

Create greater awareness in the public of successes and failures in universal design.

It is critical to formalize and document, in the form of qualitative criteria and quantitative guidelines and standards, the expected performance of facilities in terms of universal design.

FIGURE 2-6 Universal design principles versus performance criteria.

FIGURE 2-7 Universal design evaluation: process model with evolving performance criteria.

POSSIBLE STRATEGIES FOR UNIVERSAL DESIGN EVALUATION

In the above-referenced models, it is customary to include Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) standards for accessible design as part of a routine evaluation of facilities. The ADA standards provide information on compliance with prescriptive technical standards, but say nothing about performance—how the building or setting actually works for a range of users. The principles of universal design (Center for Universal Design, 1997) constitute an idealistic, occupant need-oriented set of performance criteria and guidelines that need to be operationalized. There is also the need to identify and consider data-gathering methods that include interviews, surveys, direct observation, photography, and the in-depth case study approach, among others.

Other authors address assessment tools for universal design at the building (Corry, 2001) and urban design scales (Guimaraes, 2001; Manley, 2001). In addition, the International Building Performance Evaluation project (Preiser, 2001) and consortium created by the author has attempted to develop a universal data collection tool kit that can be applied to any context and culture, while respecting cultural differences.

The author proposes to advance the state of the art through a collection of case study examples of different building types, with a focus on universal design, including living and working environments, public places, transportation systems, recreational and tourist sites, and so forth. These case studies will be structured in a standardized way, including videotaped walk-throughs of different facility types and with various user types. The universal design critiques would focus at the three levels of performance referred to above (Preiser, 1983), i.e., (1) health, safety, and security; (2) function, efficiency, and work flow; and, (3) psychological, social, cultural, and aesthetic performance. Other POE examples are currently under development through the Rehabilitation Engineering and Research Center at the State University of New York at Buffalo. One study focuses on wheelchair users, another, on existing buildings throughout the United States. Its Web site explains that research in more detail (<www.ap.buffalo.edu/>)

Furthermore, methodologically appropriate ways of gathering data from populations with different levels of literacy and education (Preiser and Schramm, 2001) are expected to be devised. It is hypothesized that through these methodologies, culturally and contextu-

ally relevant universal design criteria will be developed over time. This argument is eloquently presented by Balaram (2001) when discussing universal design in the context of an industrializing nation such as India.

The role of the user as “user/expert” (Ostroff, 1997) should also be analyzed carefully. The process of user involvement is often cited as central to successful universal design but has not been systematically evaluated. Ringaert discusses the key involvement of the user, as noted above.

EDUCATION AND TRAINING IN UNIVERSAL DESIGN EVALUATION TECHNIQUES

Welch (1995) presented strategies for teaching universal design developed in a national pilot project involving 21 design programs throughout the United States. The initial learning from that project can be used in curricula in all schools of architecture, industrial design, interior design, landscape architecture, and urban design, when they adopt a new approach to embracing universal design as a paradigm for design in the future. In that way, students will be familiarized with the values, concept, and philosophy of universal design at an early stage, and through field exercises and case study evaluations, they will be exposed to real-life situations. As noted in Welch, it is important to have multiple learning experiences. Later on in the curriculum, these first exposures to universal design should be reinforced through in-depth treatment of the subject matter by integrating universal design into the studio courses, as well as evaluation and programming projects.

A number of authors, including Jones (2001), Pedersen (2001), and Welch and Jones (2001), offer current experiences and future directions in universal design education and training.

CONCLUSIONS

For universal design to become viable and truly integrated into the building delivery cycle of mainstream architecture and the construction industry, it will be critical to have all future students in these fields familiarized with universal design, on one hand, and to demonstrate to practicing professionals the viability of the concept through a range of POE-based UDEs, including exemplary case study examples, on the other.

The “performance concept” and “performance criteria” made explicit and scrutinized through post-occupancy evaluations have now become an accepted part of good design by moving from primarily subjective, experience-based evaluations to more objective evaluations based on explicitly stated performance requirements in buildings.

Critical in the notion of performance criteria is the focus on the quality of the built environment as perceived by its occupants. In other words, building performance is seen to be critical beyond aspects of energy conservation, life-cycle costing, and the functionality of buildings: it focuses on users’ perceptions of buildings.

For data-gathering techniques for POE-based UDEs to be valid and standardized, the results need to become replicable.

Such evaluations have become more cost-effective due to the fact that shortcut methods have been devised that allow the researcher or evaluator to obtain valid and useful information in a much shorter time frame than was previously possible. Thus, the cost of staffing evaluation efforts, plus other expenses have been considerably reduced, making POEs affordable, especially at the “indicative” level described above.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Wolfgang Preiser is a professor of architecture at the University of Cincinnati. He has more than 30 years of experience in teaching, research, and consulting, with special emphasis on evaluation and programming of environments, health care facilities, public housing, universal design, and design research in general. Dr. Preiser has had visiting lectureships at more than 30 universities in the United States and more than 35 universities overseas. As an international building consultant, he was cofounder of Architectural Research Consultants and the Planning Research Institute, Inc., both in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He has written and edited numerous articles and books, including Post-Occupancy Evaluation and Design Intervention: Toward a More Humane Architecture. Dr. Preiser is a graduate fellow at the University of Cincinnati. He received the Progressive Architecture Award and Citation for Applied Research, and the Environmental Design Research Association (EDRA) career award. In addition, he was a Fulbright fellow and held two professional fellowships from the National Endowment of the Arts. He is a member of the editorial board of Architectural Science Review; associate editor of the Journal of Environment and Behavior; and a member

and former vice-chair and secretary of EDRA. He is cofounder of the Society for Human Ecology (1978). In the mid-1980s, he chaired the National Research Council Committee on Programming Practices in the Building Process and the Committee on Post-Occupancy Evaluation Practices in the Building Process. Dr. Preiser holds a bachelor’s degree in architecture from the Technical University, Vienna, Austria; a master of science in architecture from Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University; a master of architecture from the Technical University, Karlsruhe, Germany; and, a Ph.D. in man-environment relations from Pennsylvania State University.

REFERENCES

Baird, G., et al. (Eds.) (1996). Building Evaluation Techniques. London: McGraw-Hill.

Balaram, S. (2001). Universal design and the majority world. In: Preiser, W.F.E., and Ostroff, E. (Eds.) Universal Design Handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Center for Universal Design (1997). The Principles of Universal Design (Version 2.0). Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina State University.

Corry, S. (2001). Post-occupancy evaluation and universal design. In: Preiser, W.F.E., and Ostroff, E. (Eds.) Universal Design Handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Farbstein, J., et al. (1989). Post-occupancy evaluation and organizational development: The experience of the United States Post Office. In: Preiser, W.F.E. (Ed.) Building Evaluation. New York: Plenum.

Guimaraes, M.P. (2001). Universal design evaluation in Brazil: Developing rating scales. In: Preiser, W.F.E., and Ostroff, E. (Eds.) Universal Design Handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Jones, L. (2001). Infusing universal design into the interior design curriculum. In: Preiser, W.F.E., and Ostroff, E. (Eds.) Universal Design Handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Mace, R., G. Hardie, and J. Place (1991). Accessible Environments: Toward universal design. In: Design Intervention: Toward a More Humane Architecture. Preiser, W.F.E. Vischer, J.C. and White. E.T. (Eds.) New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Manley, S. (2001). Creating an accessible public realm. In: Preiser, W.F.E., and Ostroff, E. (Eds.) Universal Design Handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Maslow, H. (1948). A theory of motivation. Psychological Review 50: 370-398.

Nasar, J.L. (Ed.) (1988). Environmental Aesthetics: Theory, Methods and Applications. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Ostroff, E. (1997). Mining our natural resources: the user as expert. Innovation, The Quarterly Journal of the Industrial Designers Society of America 16(1).

Pedersen, A. (2001). Designing cultural futures at the University of Western Australia. In: Preiser, W.F.E., and Ostroff, E. (Eds) Universal Design Handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Preiser, W.F.E. (1983). The habitability framework: A conceptual approach toward linking human behavior and physical environment. Design Studies 4 (No. 2)

Preiser, W.F.E. Rabinowitz, H.Z., and White, E.T. (1988). Post-Occupancy Evaluation. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Preiser, W.F.E. (1991). Design intervention and the challenge of change. In: Preiser, W.F.E., Vischer, J.C., and White, E.T., (Eds.) Design Intervention: Toward a More Humane Architecture. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Preiser, W.F.E. (1996). POE Training Workshop and Prototype Testing at the Kaiser-Permanente Medical Office Building in Mission Viejo, California, USA . In Baird, G., et al. (Eds.) Building Evaluation Techniques. London: McGraw-Hill.

Preiser, W.F.E., and Stroppel, D.R. (1996). Evaluation, reprogramming and re-design of redundant space for Children’s Hospital in Cincinnati. In: Proceedings of the Euro FM/IFMA Conference, Barcelona, Spain, May 5-7.

Preiser, W.F.E. (1997). Hospital activation: Towards a process model. Facilities 12/13; 306-315.

Preiser, W.F.E. and Schramm, U. (1997). Building performance evaluation. In: Watson, D., Crosbie, M.J. and Callendar, J.H. (Eds.) Time-Saver Standards: Architectural Design Data. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Preiser, W.F.E. (1998). Health Center Post-Occupancy Evaluation: Toward Community-Wide Quality Standards. Sao Paulo, Brazil: Proceedings of the NUTAU/USP Conference.

Preiser, W.F.E. (1999). Post-occupancy evaluation: Conceptual basis, benefits and uses. In: Stein, J.M., and Spreckelmeyer, K.F. (Eds.) Classical Readings in Architecture. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Preiser, W.F.E. (2001). The International Building Performance Evaluation (IBPE) Project: Prospectus. Cincinnati, OH: University of Cincinnati. Unpublished Manuscript.

Preiser, W.F.E. and Schramm, U. (2001). Intelligent office building performance evaluation in the cross-cultural context: A methodological outline. Intelligent Building I(1).

Vitruvius (1960). The Ten Books on Architecture (translated by M.H. Morgan) New York: Dover Publications.

von Foerster, H. (1985). Epistemology and Cybernetics: Review and Preview. Milan: Casa della Cultura.

Watson, D., Crosbie, M.J., and Callender, J.H. (Eds.) (1997). Time-Saver Standards: Architectural Design Data. New York: McGraw-Hill (7th Edition).

Welch, P. (Ed.) (1995). Strategies for Teaching Universal Design. Boston, Mass: Adaptive Environments Center.

Welch, P., and Jones, S. (2001). Teaching universal design in the U.S. In: Preiser, W.F.E., and Ostroff, E. (Eds.) Universal Design Handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill.