Learning from Our Buildings: A State-of-the-Practice Summary of Post-Occupancy Evaluation (2001)

Chapter: Appendix A Functionality and Serviceability Standards: Tools for Stating Functional Requirements and for Evaluating Facilities

Appendix A

Functionality and Serviceability Standards: Tools for Stating Functional Requirements and for Evaluating Facilities

Françoise Szigeti and Gerald Davis, International Centre for Facilities

INTRODUCTION: THE FUNCTIONALITY AND SERVICEABILITY TOOLS HAVE STRONG FOUNDATIONS1

The functionality and serviceability tools are founded in part on “the performance concept in building,” which has roots before World War II in Canada, the United States, and overseas. In the United States in the 1950s and 1960s, the Public Buildings Service (PBS) of the General Services Administration (GSA) funded the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST, then the National Bureau of Standards) to develop a performance approach for the procurement of government offices, resulting in the so-called Peach Book publication (NBS, 1971). Starting in the early 1980s, the performance concept was applied to facilities for office work and other functions by the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) Sub-committee E06.25 on Whole Buildings and Facilities. Worldwide, in 1970, the International Council for Building Research Studies and Documentation (commonly known as CIB) set up Working Commission W060 on the Performance Concept in Building. In 1982, the coordinator for that commission defined the concept in those terms: “The performance approach is, first and foremost, the practice of thinking and working in terms on ends rather than means. It is concerned with what a building is required to do, and not with prescribing how it is to be constructed” (Gibson, 1982). In 1998, the CIB launched a proactive program for the period 1998-2001 focused on two themes: the performance-based building approach, and its impact on standards, codes and regulations, and sustainable construction and development.2

By 1985, the importance of distinguishing between performance and serviceability had been recognized, and standard definitions for facility and facility serviceability were developed. Facility performance is defined by ASTM as the “behaviour in service of a facility for a specified use,” while facility serviceability is the “capability of a facility to perform the function(s) for which it is designed, used, or required to be used.” Both definitions are from ASTM Standard E1480. Serviceability is more suited than performance to responding to the stated requirements for a facility, because the focus of performance is only on a single specified use or condition, at a given point in time, whereas serviceability deals with the capability of a facility to deliver a range of performance over time. In the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), related work has been carried out within ISO/Technical Committee 59/Sub-Committee 3 on Functional/User Requirements and Performance in Building Construction.

The term programme, meaning a statement of requirements for what should be built, was in common usage in the mid-nineteenth century by architectural students at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris and, thereafter, in American universities as they adopted the French system. In North America, the architect’s basic

|

1 |

For further information and details, see Szigeti and Davis, (1997) in Amiel, M. S., and Vischer, J. C., Space Design and Management for Place Making Proceedings of the 28th Annual Conference of the Environmental Design Resarch Association, The Environmental Design Research Association (EDRA), Edmond, Okla., 1997. |

|

2 |

CIB Pro-Active Program, see CIB Web site for further details at <www.cibworld.nl>. |

services included architectural programming (i.e., “confirming the requirements of the project to the owner”), but excluded setting functional requirements, which was the owner’s responsibility. In Britain and parts of Canada, the term “briefing” includes programming. By the mid-twentieth century, some clients for large or complex projects paid extra to have their architects or management consultants prepare a functional program for their projects.3 The functionality and serviceability tools were created to make it easier, faster, and cheaper to create such functional programs in a consistent and comprehensive manner, to link requirements to results, and to evaluate performance against requirements.

There is now a worldwide trend toward the use of a “performance-based approach” to the procurement, delivery, and evaluation of facilities. This approach is useful because it focuses on the results, rather than on the specification of the means of production and delivery. It reduces trade barriers and promotes innovation or at least removes many impediments to innovation. For such an approach to be successful however, there is a need for more attention to be paid to the definition and description of the purposes (demand-results), short term and long term, and for more robust ways of verifying that the results have indeed been obtained. This is why there is a mounting interest in building performance evaluations and other types of assessments. Customer satisfaction surveys, post-occupancy evaluations (POEs), lease audits, and building condition reports are becoming more common.

This appendix has four sections: (1) context, (2) measuring the quality of performance of facilities using the ASTM standards, (3) examples, and (4) final comments.

CONTEXT: PROGRAMMING AND EVALUATION AS PART OF A CONTINUUM

Feed-Forward—The Programming-Evaluation Loop

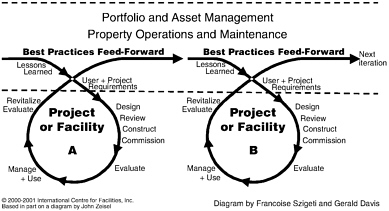

Not only do most large organizations lack a comprehensive facilities database, they also fail to develop an institutional memory of lessons learned. They are too often dependent on what best practices have been recognized and remembered by individual real estate and facility staff members and passed on informally to their subordinates and successors. Most often, such accumulated knowledge disappears with the individuals responsible. Instead, as each facility project is acquired, whether it is new construction, remodel or refit, or leased or owned, both the facility and the processes involved should be evaluated. Each phase of each project should be considered a potential source of lessons, including planning, management, programming, design, construction, commissioning, occupancy, operation, and maintenance, even decommissioning. Figure A-1 shows such an ongoing cycle of feed-forward from project to project.

To be effective, such evaluations, or programs of lessons learned, need a way to organize the information and to relate and compare it to what the client requires now and in the future. Since 1965 when TEAG—The Environmental Analysis Group/GEMH – Groupe Pour l’Etude du Milieu Humain—was launched, a programming assignment normally starts with an evaluation of the current facilities used by the client or similar surrogate facilities if need be. These evaluations give invaluable information and serve as a context for the programming process. The work then proceeds with interviews of senior managers about current problems and future expectations, and group interviews with occupants at several levels of the organization. Questions are asked about what works, not just what does not work. It is important to know what should be carried over from the current situation.

Over the years, interview guides and recording documents have been developed for such evaluations. This work and experience provided the foundation for the functionality and serviceability tools. Thus, evaluations feed into functional programs, which become the basis for the next evaluations.

Defining Requirements

The functional program should focus on aspects of the project requirements that are important for the enterprise, in order to direct the best allocation of resources within the given cost envelope. The objective is to get best value for the users and owners. A knowledgeable client will prepare, in-house or with the help of consultants, a statement of requirements (SOR), including indicators of capability of the solution that

FIGURE A-1 Feed-forward.

are easy to audit and are as unambiguous as practicable. This is an essential step of the planning phase for a project.

Portfolio management provides the link between business demands and real estate strategy. At the portfolio level, requirements are usually rolled up and related to the demands of the strategic real estate plan in support of the business plan for the enterprise (Teicholz, 2001).

Requirements for facilities needed by an enterprise will normally be included in a portfolio management strategy. An asset management plan for a facility would include the specific requirements for that facility. A statement of requirements, in one form or another, more or less adequate, is part of the contractual documentation for each specific procurement.

Statements of requirements serve as the starting point for providers of material, products, facilities, services, and so forth. As experienced readers of this report likely know, if there is ever litigation or other liability issue, then the statement of requirements is the first document that the parties will turn to. It is the reference point for any review process during tendering, design, production, and delivery, as well as for later evaluation(s), no matter which methodology is used. It is particularly necessary for performance-based and design-build procurement and for any project developed using an integrated project team approach. In the more traditional approach, the contractual documents normally include very precise specifications (“specs”). In the experience of expert witnesses, the root of many court cases and misunderstandings can be traced back squarely to badly worded, imprecise, incomplete statements of requirements that do not include any agreed means of verifying whether the product or service delivered is in fact meeting the stated requirements.

In a performance-based approach and for design-build and similar procurements, the focus is on the expected performance, or on a range of performances, of the end product. Therefore, the heart of these nontraditional approaches is defining those expected results and the requirements of the customer or user in an objective, comprehensive, consistent, and verifiable manner. In any dispute, it is necessary to be able to go back to the contract and have a clear definition of what was agreed between the parties. If the “legal” name of the game is a “warranty of fitness for purpose,” then the purpose has to be clearly spelled out, as well as the ways to verify that “fitness.” This point is developed further later in this appendix.

Life Cycle of Facilities, Shared Data, and Relationship to the Real Estate Processes of the Enterprise

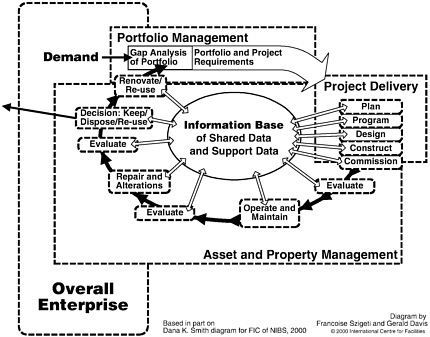

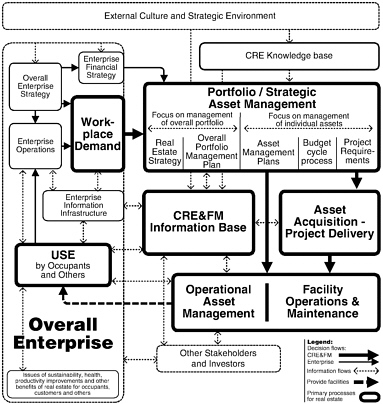

For each facility, the information included in the asset management plan, plus the more detailed programming data and the financial data, are the foundation for the cumulative knowledge base of shared data and support data about the facilities diagrammed at the center of Figure A-2. Throughout the life cycle of a facility, many people, such as portfolio and facility managers, users, operations and maintenance staff, financial managers, and others, should be able to contribute to and access this pool of data, information, and knowledge.

Today, these kinds of data and information are still mostly contained in “silos,” with many disconnects between the different phases of the life cycle of a facility. Too often the data are captured again and again, stored in incompatible formats and difficult to correlate and keep accurate. The use of computerized databases and the move to Web-based software applications and projects are steps toward the creation of a shared information base for the management of real estate assets. Once such shared databases exist, the value of evaluations and benchmarking exercises will increase because the information will be easier to retrieve when needed. The shared data and knowledge base will also make it easier to “ close the loop” and relate the facilities delivered to the demands of the enterprise.

In discussions at the Facilities Information Council of the National Institute of Building Sciences, such recreation of data over and over again has been identified as a major cause of wasted dollars and the source of potential savings. More important will be the reductions in misunderstandings, the increased ability to pin-

FIGURE A-2 Life cycle of facilities.

point weak links in the information transfer chain, and the improvements in the products and services because the lessons learned will not be lost.

For evaluations to yield their full potential as part of the life-cycle loop, the information that is fed forward from such activities needs to be captured and presented in comparable formats. Accepted terminology, standard definitions, and normalized documentation will make such comparisons much easier. The links between evaluations and stated requirements should be explicit and easy to trace.

Figure A-2 diagrams the life cycle of a facility, including the particular points in the cycle when most evaluations occur. It shows in greater detail how one of the feed-forward loops unfolds. During project delivery, of course, there are or should be evaluation loops that cannot be shown in the overall diagram.

Evaluations: From Strategic to In-Depth

Evaluations can happen at any time and can be triggered by many situations. They range in their approach from the perceptual to the performance-based to the specific and technical. At the moment, there is not yet any consensus as to what kinds of evaluations should be done and when or how they should be done. Even the terminology is in great flux. Many terms are used, such as analysis, assessment, audit, evaluation, investigation, rating, review, scan, and so forth, usually together with some qualifier, such as building condition report, building performance evaluation, facility assessment, post-construction evaluation, post-occupancy evaluation, serviceability rating, etc.

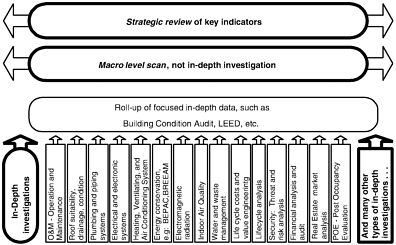

The range of tools, methods, and approaches to evaluations is quite wide as well as deep. In some situations, it is appropriate to take a broad strategic view and to use tools that can give answers quickly and with the minimum of effort. At the other extreme, there are situations that call for in-depth, specific, narrowly focused, very technical engineering audits that can take weeks and require sophisticated instrumentation. Figure A-3 shows the relationship between these different levels of precision.

FIGURE A-3 Strategic to in-depth evaluations. Source: Francoise Szigeti and Gerald Davis, © 1999, 2000 International Centre for Facilities.

MEASURING AND MANAGING THE QUALITY OF PERFORMANCE OF FACILITIES USING THE ASTM STANDARDS ON WHOLE BUILDING FUNCTIONALITY AND SERVICEABILITY

Assessing Customer Perception and Quality of Performance

Assessing customer perception and satisfaction, or evaluating the quality of the performance delivered by a facility in support of customer requirements are two complementary, but not identical, types of assessments. In a recent issue of Consumer Reports, there is a series of items dealing with the ratings of health maintenance organizations. In one of the articles, the question of the quality of the ratings is posed and an important point is made. “Satisfaction measures are important. But, don’t confuse them with measures of medical quality…” (Consumer Reports, 2000). The key point is that measuring customer satisfaction is important and necessary, but not sufficient.

There is a need for measuring the actual quality and performance of the services and products delivered, whether it be medical care or the facilities and services they provide in support of the occupants and the enterprise.

Defining Quality

Quality is described in ISO 9000 as the “totality of features and characteristics of a product or service that bear on its ability to satisfy stated and implied needs” (ISO, 2000). Quality is also defined as “fitness for purpose at a given cost.” The difference between Tiffany quality and Wal-Mart quality does not need to be explained. Both provide quality and value for money. Both are appropriate, depending on what the customer is looking for, for what purpose, and at what price.

Quality therefore is not absolute. It is the most appropriate result that can be obtained for the price one is willing to pay. Again, in order to be able to evaluate and compare different results or offerings, and verify whether the requirements have been satisfied, these must be stated as clearly as possible.

Measuring and Managing the Quality of Performance

Many enterprises, public and private, review the project file during commissioning, or later, and note whether the project was completed within budget and on schedule. Some do assess how well each new or remodeled facility meets the need of the business users who occupy it. Essential knowledge can be captured as part of a formal institutional memory of what works well, what works best, and what should not be repeated. There are an array of different methods and tools that can be used to capture this information. A number of those tools have been catalogued by a group of researchers and practitioners based at the University of Victoria at Wellington, New Zealand (Baird et al., 1996).

A quality management (or assurance) program needs to measure and track performance against “stated requirements.” Those who provide a product or service (e.g., a facility and its operations and management), should ascertain the explicit and implicit requirements of the customers (occupants), decide to what level those needs should be met, meet that level consistently, and be able to show that they are in fact meeting those requirements within the cost envelope.

Such programs, therefore, need to start with an appropriate process for preparing statements of requirements. These should include the ability to determine and assess features and characteristics of the product or service considered; to relate them directly to customers’ needs, expectations, and requirements; and to document it all in a systematic, comprehensive, and orderly manner. Such documentation should include the means to monitor compliance during all phases of the life cycle of the facility. When dealing with facilities, information should also be included about how the enterprise is organized and its business strategy, and about expectations related to quantity, constraints, environmental and other impacts, time, costs, and so forth. All these elements have to be taken into consideration when conducting an overall evaluation, in particular at the time of commissioning or shortly thereafter.

Using the ASTM Standards on Whole Building Functionality and Serviceability to Measure Quality

The information provided by most POEs and by customer satisfaction surveys is primarily about occupant perception and satisfaction, which is often necessary but rarely sufficient. It is seldom specific enough to be acted upon directly. Similarly, in-depth and specific technical evaluations usually do not address topics directly related to the functional requirements of the users or cannot be matched to those requirements.

Based on some 30 years of experience with both programming and evaluation, over the period 1987-1993,

the International Centre for Facilities (ICF) team created a set of scales that have now become the ASTM standards on whole building functionality and serviceability, recognized as American National Standards (ANSI). More importantly, these standards are based on a methodology for creating such scales that is currently being balloted at the international level under the authority of ISO TC 59/SC3 on Functional/User Requirements and Performance in Building Construction (ASTM, 2000).

These standards do provide information that can be acted upon. They measure the quality of services delivered by the facility in support of the occupants as individuals and as groups. The results from serviceability ratings complement POEs and can be cross-referenced to customer satisfaction surveys (see examples in “Final Comments”). These standards currently provide explicit, objective, consistent methods and tools and include the means to monitor and verify compliance with respect to office facilities. The usefulness of such structured information goes beyond a single project. It can also be used for lessons-learned programs and for benchmarking. The methodology could be applied equally well to create a set of tools for measuring the quality of performance of any capital asset, including all types of constructed assets, whether public infrastructure such as bridges, roads, and utilities, or buildings.

This new generation of tools gives real estate professionals the means to evaluate the “fit” between facilities and the users they serve. These tools use indicators of capability to assess how well a proposed design, or an occupied facility, meets the functional requirements specified by the business units and facility occupants. Even a small business, with only a few dozen staff, needs to capture and conveniently access the key facts about its workplaces, how they are used, and lessons to apply “next time.”

Functionality and Serviceability: Matching User Requirements (Demand) and Their Facilities (Supply)

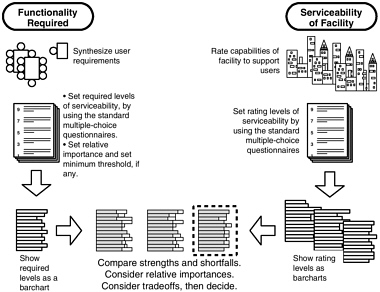

Evaluations are most useful when they provide the means to compare results to expectations. Figure A-4 shows the use of bar-chart profiles to match functional requirements and serviceability ratings using the ASTM standard scales.

ASTM Standard Scales

The ASTM standard scales provide a broad-brush, macro level method, appropriate for strategic, overall decision-making. The scales deal with both demand (occupant requirements) and supply (serviceability of buildings) (MacGregor and Then, 1999). They can be used at any time, not just at the start of a project. In particular, they can be used as part of portfolio management to provide a unit of information for the asset management plan, on the one hand, and for the roll-up of requirements of the business unit, on the other.

The ASTM standard scales include two matched, multiple-choice questionnaires and levels. One questionnaire is used for setting workplace requirements for functionality and quality. It describes customer needs—demand—in everyday language, as the core of front-end planning. The other, matching questionnaire is used for assessing the capability of a building to meet those levels of need, which is its serviceability. It rates facilities—supply—in performance language as a first step toward an outline performance specification.

Both cover more than 100 topics and 340 building features, each with levels of service calibrated from 0 to 9 (less to more). These standard scales are particularly suitable as part of the front end for a design-build project, to compare several facilities on offer to buy or lease. The scales can also be used to compare the relative requirements of different groups.

This set of tools was designed to bridge between “functional programs” written in user language on the one side and “outline specifications and evaluations” written in technical performance language on the other. Although it is a standardized approach, it can easily be adapted and tailored to reflect the particular needs of a specific organization.

For organizations with many facilities that house similar types of functions, the functionality and serviceability scales capture a systematic and consistent record of the institutional memory of the organization. Their use speeds up the functional programming process and provides comprehensive, systematic, objective ratings in a short time.

The Serviceability Tools and Methods (ST&M) Approach

The ST&M approach (Davis et al., 1993) includes the use of the ASTM standards, and its results, but also

FIGURE A-4 Matching demand and supply—gap analysis. Source: Francoise Szigeti and Gerald Davis, © 1999, 2000 International Centre for Facilities.

provides formats for describing the organization, function-based tools for estimating how much floor area an organization needs, and other tools necessary to provide needed information for the statement of requirements (SOR).

At the heart of this approach is the process of working with the occupant groups during the programming phase of the project cycle, as well as during any evaluation phase. This process of communication between the providers of services and products (in-house and external) and the other stakeholders (in particular the occupants), of valuing their input, and of being seen to be responsive can be as important as the outcome itself and will often determine the acceptability of the results.

This is where satisfaction and quality overlap. ST&M includes several kinds of methods and tools, along with documents and computer templates for using them:

-

Functional requirement bar-chart profile and functional elements

-

Facility serviceability bar-chart profile and indicators of capability

-

A match between two profiles and comparisons with up to three profiles

-

A gap analysis and selection of “strength and concerns” for presentation to senior management

-

Text profiles for use in a statement of requirements and equivalent indicators of capability

-

Descriptive text about the organization, its mission, relevant strategic information, and other information about the project in a standard format

-

Quantity spreadsheet profiles

-

Building loss features (BLF) rating table

-

Footprint and layout guide

The ASTM standards and the ST&M approach are project independent. Requirements profiles can be prepared at any time, and serviceability ratings can be done and updated at a number of points over the life cycle of a facility.

How Do These Tools Fit in the Overall Corporate Real Estate Framework?

Setting requirements and evaluating results are two parts of what should be an ongoing dialogue between users and providers. Evaluations are becoming an indispensable tool for decision-making by senior management and for appropriate responsiveness by all those involved, whether they are working in-house or are external providers.

Facilities are an important resource of the enterprise. There are three main processes to take into account: (1) demand; (2) management, planning, procurement, production, and delivery; and (3) operations, maintenance, and use.

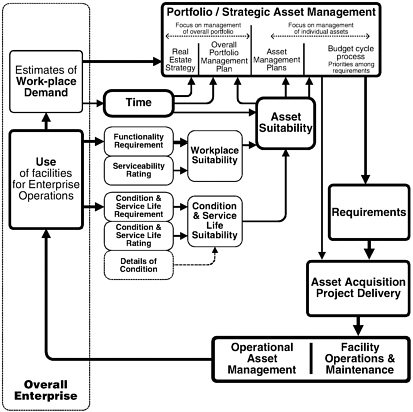

Figure A-5 shows how the different processes involved relate to each other and to the enterprise.

In Figure A-6, the functionality and serviceability scales are shown as an overlay on this framework. In this manner, it is possible to see how they relate to the underlying corporate real estate processes. The processes diagrammed here are each complex sets of activities and secondary processes. A detailed map of such activities is included in the next volume of scales to be published by the ICF (Davis et al., in press).

Figure A-6 also shows the relationship to a new set of scales prepared to rate the condition and estimated residual service life of a facility, to compare them to the needs of the enterprise. These scales are also used

FIGURE A-5 Corporate real estate processes—linking to the enterprise. Source: Francoise Szigeti and Gerald Davis, © 1999, 2000 International Centre for Facilities.

FIGURE A-6 Corporate real estate processes and use of the serviceability tools. Source: Francoise Szigeti and Gerald Davis, © 1999, 2000 International Centre for Facilities.

for setting budget priorities for repair and alteration projects.

EXAMPLES: USES OF THE ASTM STANDARDS AND LINKS TO OTHER TOOLS

Link to GSA’s Customer Satisfaction Survey: GSA, John C. Kluczynski Building, Chicago

GSA regularly assesses the satisfaction of occupants of its major buildings, using a version of the customer satisfaction survey developed by the International Facility Management Association. The satisfaction levels of occupants of its landmark John C. Kluczynski Building in downtown Chicago were compared to levels in a serviceability rating of the building and to functionality requirement profiles for the main categories of occupant groups.

The results correlated closely. The serviceability levels both predicted and explained the satisfaction levels. However, the customer satisfaction survey had more detail about how occupants felt about the speed

and thoroughness with which building operations staff responded to problems and complaints. The serviceability scales gave more information about actual strengths and concerns of the facility to meet occupant functional needs.

Together, these two complementary studies provided needed supporting information to submissions for the funding of several renovation projects. An example of a bonus from the functionality and serviceability project was the identification of ongoing security concerns of the staff. Occupants did not realize that the situation had been remedied and that thefts had been reduced by three-quarters since the assignment of a policeman in uniform on-site, patrolling the corridors. On the basis of this particular finding, a communications and public relations effort was launched to inform the staff of the beneficial impact of the presence of the uniformed policeman.

Link to Prior POEs: U.S. State Department

During the 1990s, the U.S. State Department conducted POEs after many major projects. The findings from these projects were analyzed by in-house staff and others of the Office of Foreign Buildings Operations (now Office of Overseas Buildings Operations). Then, in the late 1990s, a functionality requirement profile was developed for chanceries, using the ASTM standard scales. Data, as well as insights, from the POEs were taken into account in setting requirement levels and in preparing the main requirement profile for a base building as well as for the variant profiles for the different zones in a chancery. The ASTM standard scales provided a structure for applying the information from the POEs, which could then be directly related to equivalent levels of serviceability.

Part of Asset Management Plans: Public Works and Government Services Canada

When the serviceability tools and methods were first developed, the government of Canada rated the serviceability of all its major office buildings across the country. Recently, it has issued contracts to update the asset management plans of all its major office buildings. Each plan is required to contain a serviceability rating using the standard serviceability scales.

Part of Tool Kit for Portfolio Management and Setting Budget Priorities for Repair and Alteration Projects: PG&E

Pacific Gas & Electric Corporation (PG&E) has realigned the way it plans and manages its portfolio of real estate and sets priorities in its annual budget for repairs and alterations. Integral to its new management approach are the ASTM standard scales, the serviceability tools and methods including the new scales for building condition, and estimated remaining service life. These ratings are compared to the required level set for that facility.

New Design: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

The groups that operate the weather satellites of NOAA needed a new headquarters building. Their functional requirements were specified using the ASTM standard scales. Their requirement profile was then compared to that of private sector organizations doing similar work, such as the headquarters of a gas pipeline company or the headquarters of a mobile phone company. NOAA’s requirement profile was very similar to what was needed by other organizations doing similar kinds of work; there were very few differences. This provided a kind of benchmarking for NOAA’s senior management and showed that NOAA’s requirements were appropriate and consistent with private sector practice, even though they were much more demanding than would typically be provided for a general administrative office in government.

Choosing a Lease Property: U.S. State Department, Passport Office

The U.S. State Department and GSA reached agreement on the functionality requirement profile for its passport offices where citizens can come to have their applications adjudicated and a passport issued quickly. When new leased office space was needed for its passport office in New Orleans, the requirement profile was verified for its applicability to this particular office. Then about a quarter of the requirement scales were used to scan the properties on offer that GSA had identified as relevant. In two days, six properties were scanned for serviceability levels. Only one out of six

was found to meet the essential functionality requirements. However, once the real estate manager in GSA understood the requirement profile of the occupant group, she was quickly able to identify two other valid options. Within weeks, the “best fit” was identified, and a lease negotiated.

Requests for Proposals (RFPs) and Design Reviews: State Department Chanceries and High-Tech Organizations

During 1999 and 2000, the U.S. State Department used its functionality requirement profile and serviceability indicators to assess the functionality of design proposals for new embassies and consulates to be developed in the sequential project development process, design-bid-build. The department’s requirement profile was also used to assess and compare the functionality of proposals using the integrated, design-build procurement process. In some cases, proposals had very similar levels of functionality, while some other proposals showed significant differences between the functionality of the proposals and what had been required.

Thereafter, the same requirement profile was used during design reviews as a benchmark to ensure that the designs were continuing to respond to the requirements stated in the RFP. Contractors were trained to do these assessments, to create comparisons bar-charts, and to analyze the gaps between the designs and the requirement profile.

When a slow-growth, high-tech corporation needed a new corporate headquarters, it developed a functional requirement profile in the language and format of the ASTM standards and included it, verbatim, in its RFP. Responses to the RFP were rated, using the serviceability scales. Although a number of the proposals were fairly tightly clustered on price, there was a significant difference in functionality among the proposals.

Levels of Service for Outsourcing: A Major Oil Company

When a major oil company was considering outsourcing its facility management operations, it asked all companies who proposed to base their cost proposals on using the same levels of serviceability, as specified using the ASTM standard serviceability scales. Senior management also asked the “in-house provider” to self-rate using the same standards. Both the in-house facilities group and the bidders were able to do this on short notice, without having received any special training or guidance in using the standards. Comparable proposals, based on these consistent requirements, were received on schedule without difficulty. This company also asked TEAG to rate its main campus and to prepare a profile of requirement for the largest occupant group housed at that campus. This third-party assessment served as a benchmark to compare the results from the other assessments and proposals.

FINAL COMMENTS

Some Relevant Anecdotes

The value of a property and its long-term benefits are not just a matter of real estate dollars and cents and technical performance; corporations also look at the effectiveness of the workplace for core business operations and at the strategic advantage that facilities can provide. Successful facilities and real estate groups understand this (FFC, 1998). It can cost or earn the company far more than the rise or fall of property prices. For example, one vice president for facilities at an aircraft company explained to us that facilities costs represent about 5 percent of the total cost of each airplane sold, but that 5 percent is critical to the ability of his company to deliver new planes on time and on budget. If a new hangar is not ready on time or the facilities get in the way, the whole production line can be delayed or grind to a halt. The same holds true for smaller companies who rent office space. For them the cost of rent, utilities, and other charges runs at about the same percentage.

For organizations, big or small, a 1 percent increase (or decrease) in the productivity of core business operations, brought about by an inadequate workplace, is probably at least 10 times greater than a 1 percent increase (or decrease) in the value of the real property considered as a real estate asset. Put another way, here is the example of a laboratory where facilities were underused and inefficient: At zero facilities cost and with minimum rearrangements, an extra 15 scientists could be added. This would give the lab extra gross revenue while lowering the cost of square feet per employee. On the other hand, more substantial changes in the facility layout would allow the lab to nearly double its population. This retrofit would cost far less than the cost of a new facility. Other functional improvements would increase the effectiveness of the

staff by about 15 percent and speed time to market by about six months. All of these proposed changes were based on an assessment of functional capability. Overall, the asset value in use was expected to increase by more than $3,000,000, after taking into account retrofit costs. The earning power of the lab would be multiplied by almost 2.5. These numbers were calculated by one of the major accounting firms. Thus, typically, the greatest leverage for a facility comes from enhancing the performance of the core business. A factor of 10 or more is not unusual.

The effect of a facility on the health of its occupants can have a severe impact on productivity. Medical records are seldom used to prove this point but probably could be used more often. On one occasion, ICF was allowed to use records of sick days as part of a comprehensive facility evaluation after a major consolidation of staff into a single facility. After plotting the sick leave information for each of 18 groups for the year prior to the move, the year of the move, and the first year after the move, it became apparent that for all but two groups, the curve shifted up. For two groups, the curve shifted down. For those two groups, the building they came from was worse than the new facility. It was estimated that the number of days lost to the increased sick leave and a few other facility-related factors amounted to more than the annualized first cost of the building.

Sometimes, the effect of the facility can be drastic and immediate. In one case, due to some work being done in one part of the facility, traffic was redirected along an internal corridor cutting through the “territory” of a work group. What had been a “private path” was transformed overnight into a “major highway” (Davis and Altman, 1976). The partitions around that group were glass above 1 meter, which allowed passers-by to see into the space. ICF had warned that such a situation should not be allowed to happen because of the “fish-bowl” effect. The group in question was working on a critical path product that was at the heart of the future of the company and still highly secret. The group simply stopped work and did not put work on their desks. When the ICF team arrived onsite that day, it was asked to come directly to the office of the senior manager responsible for facilities. A work crew was commandeered to work overnight. Butcher paper was pasted over the glass to create visual privacy. By the next morning the problem had been solved, and work resumed.

In another case, staff retention was the victim. A major industrial corporation was recruiting young engineers to replenish its aging population, but these were leaving the company in record numbers after three months or less on the job. The human resources department conducted exit interviews to find out what the problem was. The young recruits reported that the space they were asked to work in was so unpleasant and antiquated that they felt the company had no regard for them. The job market at that time was good, and they could get jobs at other companies offering comparable salaries and much more attractive and modern facilities. This caused the company to start a $300 million rehabilitation program of its offices and to generally pay more attention to the physical setting of work.

Facilities have an impact when attracting staff, which can be the reverse of the last anecdote. Another major industrial company reported that it was located in an industrial area with other competitors. Its policy was to make its grounds attractively landscaped and to provide each of its software engineers with a private, well-furnished office with a window overlooking trees and flowers. The human resources department at that company could confirm that this “perk” was worth about 10 percent of payroll, that is, more than the annualized cost of the buildings and grounds.

Current Developments and Trends

Scales for Rating Condition and Estimated Remaining Service Life

As stated earlier, new scales have been developed by the ICF to enable a manager to set priorities for repair and alteration projects in the annual budget cycle. These scales are used for building condition, estimated service life, and asset management. They have been designed to assist managers to take into account the actual and required physical condition and estimated remaining service life of a facility or of its main systems and components. Typically, building condition reports give cost estimates to return a building to its original design but do not link directly to the level of functional support now required for occupant operations. These new scales can be matched directly, for gap analysis against the condition requirement profile in the asset management plan and overall portfolio management plan. They complement the information about the functional suitability of the facility to support the mission of the occupant group.

Scales for Other Building Types

A set of scales, similar to the ASTM standards, has been drafted for low-income housing and is being tested in New Zealand (Gray, 2001).

ICF has just completed additional scales for service yards and maintenance shops. Scales are also being developed to better cover sustainable building, manufacturing, retail, laboratories, education, health care, courts, and so forth.

Integrated Tools for Performance-Based Procurement

The Dutch government has mandated that all public procurement be performance based. With the ASTM standards as a starting point, the Dutch Building Agency has developed a systematic approach to define client expectations for total building performance (Ang et al., 2001). This approach also relates the translation of “inputs” and “outputs” at different phase of the project delivery process.

Strategic Asset Management

In some countries, portfolio management and strategic planning come under the term “strategic asset management” (SAM). In these places, asset is the preferred term, rather than facilities or buildings, of public sector managers who deal with all kinds of constructed capital assets, many of which may not be buildings. One of the most pertinent publications on the subject is a newsletter dedicated to the international review of all areas of performance and strategic management of assets, including economic considerations. Linking performance evaluations and costs is still a tricky business. Some of the concepts, such as profiles, levels of service, benchmarking targets, etc., which are becoming part of the performance evaluation, are explained in the newsletter in a practical and approachable way, with an emphasis on sharing of experience (Burns).

Levels of Service, Performance Profiles, Performance Benchmarks

The use of levels, or targets, is becoming prevalent for outsourced contracts, for performance-based procurements, and for strategic planning. The Department for Administrative and Information Services of the state of South Australia, is currently developing a building performance assessment and asset development strategy, which adapts some of the ASTM standard scales and methodology to its own circumstances.

Warranty of Fitness for Purpose—Duty of Care Versus Duty of Results

In the wake of ISO 9000, with the advent of new integrated team approaches to projects, and performance-based procurement approaches, such as design-build, and construction manager at risk, there is an increased awareness of the need to state requirements more precisely and comprehensively and to be able to confirm that the resultant asset meets those requirements. Further, when delivering a full package, the contractor has the legal responsibility to deliver a product that fits the intended purpose. This is a major change for the traditional legal concepts of professional liability and duty of care, based on professional competence and accepted practice. This legal territory is being explored by groups such as the Design-Build Institute of America and the CIB (CIB, 1996).

In Conclusion

Evaluations are here to stay and will likely be taken for granted in the not too distant future. At a prior Federal Facilities Council (FFC) Forum, the presentation of the Amoco common process, developed by its Worldwide Engineering and Construction Division, included the following in Figure 2: “Operate—Evaluate asset to ensure performance . . . ” (FFC, 1998).

To be more effective and useful, evaluations will have to be better coordinated with the information contained in statements of requirements. At the same FFC forum, several presenters included a project system in their presentation. The presentation by the director-construction of The Business Roundtable included a description of “Effective Project Systems” developed by the Independent Project Analysis Corporation of Reston, Virginia. He made the point that “the supply chain begins when the customer need is identified and translated into a business opportunity” (FFC, 1996). In such project systems, which usually are conducted by integrated project teams, the evaluation of alternative solutions is taken for granted. Thus, evaluations are part of the planning of the projects, not an afterthought.

The worldwide trend to deal with performance definitions rather than prescriptive or deemed-to-satisfy specifications will likely continue to spread. In the next few years, a further increase in the use of evaluations

will be driven by the acceptance of performance based procurement by the World Trade Organization (WTO), the European Union, and the European member countries. Performance-based codes are also being adopted in a number of countries, including the United States.

The European Union (EU) is following suit. Since dealing with results rather than specifying solutions means that these results need to be shown to be performing as required, there is an assured future for evaluations and for evaluations as part of the process at many stages. Such developments, as they affect the building industry, will be the focus of a major thematic network being launched by the CIB, with EU funding (Bakens, 2001). This network will also include participants from the United States and other countries outside the EU. A key task will be how to prepare statements of requirements and their verification.

In the United States, a performance-based code has been adopted as a component of the new Unified International Building Code that has brought the three major codes together. Work is continuing at ASTM, the American Institute of Architects (AIA), NIST, and the GSA, to cite only a few of the key leaders. 4

Benchmarking, lessons-learned programs, continuous improvements, and performance metrics are becoming part of business as usual. Indeed, to quote again from the 1998 FFC report: “What are the characteristics of the best capital project systems? In addition to using fully integrated cross-functional teams, they actively foster a business understanding of the capital project process. . . . The engineering and project managers are accountable to the business, not the plant management. There are continuous improvement efforts that are subject to real and effective metrics” (FFC, 1998). The evolution of POEs into building performance evaluations, and now into an ongoing evaluative stance, is likely to become the accepted norm because it is part of the best practices of companies that have succeeded in using capital projects in support of their primary business.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Gerald Davis helps decision makers and facility managers implement solutions that enhance worker effectiveness, improve the management of portfolios of corporate real estate, solve facility-related problems, and ensure the optimum use of buildings and equipment. Since 1965, Mr. Davis has been considered a pioneer and internationally recognized expert in strategic facility planning, facility pre-design, programming, performance-based evaluations, and ergonomics. As senior author, he led the team that developed the Serviceability Tools & Methods® used to define workplace and facility requirements and to rate existing and proposed facilities. Previously, he led the “ORBIT-2” project, a major North American multisponsor study about offices, information technology and user organizations and about the impact of each on the other. He coauthored the “1987 IFMA Benchmark Report” which was the first of its kind. His work has been published in numerous trade and professional journals and books. He is the recipient of the Environmental Design Research Association Lifetime Career Award (1996), the IFMA Chairman’s Citation, (1998), was named an IFMA fellow in 1999, and one of 50 most influential people in the construction industry by the Ottawa Business Journal. He is an ASTM fellow, and Certified Facility Manager, president and chief executive officer, International Centre for Facilities (ICF), president, TEAG (The Environmental Analysis Group), chair, ASTM Subcommittee E06.25 on Whole Buildings and Facilities; past chair, ASTM Committee E06 on Performance of Buildings; and past chair, IFMA Standards Committee (1993-99). He is also the U.S. (ANSI) voting delegate to the ISO Technical Committee 59 on Building Construction, to its Subcommittee 3 on Functional/ User Requirements and Performance in Building Construction, and the former delegate to its Subcommittee 2 on Terminology and Harmonization of Language. Mr. Davis was recently appointed the Convenor of Work Group 14 on Functional Requirements/Serviceability.

Francoise Szigeti is the vice-president of the International Centre for Facilities, Inc., a scientific and educational public-service organization established to inform and help individuals and organizations improve the functionality, performance, and serviceability of facilities. She is also vice president and secretary-treasurer of The Environmental Analysis Group

(TEAG) - Groupe pour l’Etude du Milieu Humain (GEMH). She is president of Serviceability Tools & Methods, Inc. Ms. Szigeti is one of the vice-chairs of ASTM Subcommittee E06.25. She has served on the board of the Community Planning Association of Canada, the Environmental Design Research Association and the International Association for the Study of People and Their Physical Surroundings. She is a co-author and member of the team that developed the Serviceability Tools & Methods® used for defining workplace and facility requirements and for rating existing and proposed facilities. Previously, she launched and participated in the “ORBIT-2” project, a major North American multisponsor study about offices, information technology, and the user organizations, and about the impact of each on the other. She is a coauthor of the “1987 IFMA Benchmark Report”, which was the first of its kind. Ms. Szigeti attended the Ecole Superieure d’Interpretes et de Traducteurs, Universite de Paris. She is the recipient of the EDRA Lifetime Career Award (1996).

REFERENCES

Ang, G., et al. (2001). A Systematic Approach to Define Client Expectation to Total Building Performance During the Pre-Design Stage. Proceedings of the CIB 2001 Triennial Congress.

ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials). (2000). ASTM Standards on Whole Building Functionality and Serviceability, ASTM, West Conshohocken, Pa.

Baird, G., Gray, J., Isaacs, N., Kernohan, D., and McIndoe, G. (1996). Building Evaluation Technique. Wellington, New Zealand: McGraw Hill.

Bakens, W. (2001). Thematic Network PeBBu—Performance Based Building—Revised Workplan. Rotterdam:CIB.

Burns, P. (Ed.) SAM—Strategic Asset Management Newsletter AMQ International, Salisbury, South Australia.

CIB Publication 192. (1996). A Model Post-Construction Liability and Insurance System prepared under the supervision of CIB W087. Rotterdam, Holland.

Consumer Reports (2000). Rating the Raters, August 31.

Davis, G., and Altman, I. (1976). Territories at the work-place: Theory into design guidelines. In: Man-Environment Systems, Vol. 6-1, pp. 46-53. Also published, with minor changes, in: Korosec-Serfati, P. (Ed.) (1977). Appropriation of Space, Proceedings of the Third International Architectural Psychology Conference Strasbourg, France: Louis Pasteur University.

Davis, G., et al. (1993). Serviceability Tools Manuals, Volume 1 & 2 International Centre for Facilities: Ottawa, Canada.

Davis, G. et al. (2001). Serviceability Tools, Volume 3—Portfolio and Asset Management: Scales for Setting Requirements and for Rating the Condition and Forecast of Service Life of a Facility—Repair and Alteration (R&A) Projects. International Centre for Facilities: Ottawa, Canada.

Federal Facilities Council. (1998). Government/Industry Forum on Capital Facilities and Core Competencies. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, p. 19.

Gibson, E.J. (1982). Working with the Performance Approach in Building. CIB Report, Publication 64. Rotterdam, Holland.

Gray, J. (in press). Innovative, Affordable, and Sustainable Housing. Proceedings of the CIB 2001 Triennial Congress. Rotterdam, Holland.

ISO 9000, Guidelines 9001 and 9004. (in process of reedition).

McGregor, W., and Then, D.S. (1999). Facilities Management and the Business of Space. Arnold, a member of the Hodder Headline Group.

National Bureau of Standards. (1971). The PBS Performance Specification for Office Buildings, prepared for the Office of Construction Management, Public Buildings Service, General Services Administration, by David B. Hattis and Thomas E. Ware of the Building Research Division, Institute for Applied Technology, National Bureau of Standards. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce NBS Report 10 527.

Szigeti, F., and Davis, G. (1997). Invited paper. In: Amiel, M.S., and Vischer, J.C., Space Design and Management for Place Making. Proceedings of the 28th Annual Conference of the Environmental Design Research Association (EDRA). Edmond, Okla.: EDRA.

Teicholz, E. (Ed.) (2001). Facilities Management Handbook. MacGrawHill.