Learning from Our Buildings: A State-of-the-Practice Summary of Post-Occupancy Evaluation (2001)

Chapter: 3 Post-Occupancy Evaluation: A Multifaceted Tool for Building Improvement

3

Post-Occupancy Evaluation: A Multifaceted Tool for Building Improvement

Jacqueline Vischer, Ph.D., University of Montreal

WHAT IS POST-OCCUPANCY EVALUATION?

Various definitions of Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE) have been advanced over the last 20 years since the term was coined. Loosely defined, it has come to mean any and all activities that originate out of an interest in learning how a building performs once it is built, including if and how well it has met expectations and how satisfied building users are with the environment that has been created. POEs can be initiated as research (Marans and Spreckelmeyer, 1981), as case studies of specific situations (Brill et al., 1985), and to meet an institutional need for useful feedback on building and building-related activities (Farbstein and Kantrowitz, 1989). For some public agencies, such as the State of Massachusetts and Public Works Canada (now Public Works and Government Services Canada), POE is a mechanism for linking feedback on newly built buildings with pre-design decision-making; the goal is to make improvements in public building design, construction, and delivery.

Evidence from POE activities to date indicates that objectives such as finding out how buildings work once they are built—and whether the assumptions on which design, construction, and cost decisions were based are justified—are primarily of interest to large institutional owners and managers of real estate inventory. Tenant organizations, small owner-occupiers, and private sector commercial property managers are not typically investors in POE. Moreover, the number of large institutional owners and managers of real estate who have active POE programs is extremely small.

THE PROS AND CONS OF POE

One of the characteristics of POE activities is the discrepancy that exists between the reasons for doing POE (pros) and the difficulty of doing them (cons). Reasons for doing POEs are well represented in the literature. One reason is to develop knowledge about the long-term and even the short-term results of design and construction decisions—on costs, occupant satisfaction, and such building performance aspects as energy management, for example. Another reason is to accumulate knowledge so as to inform and improve the practices of building-related professionals such as designers, builders, and facility managers and even to inform the clients and users who are the consumers of services and products of those same building-related professionals. For an institutional owner-manager of real estate (government agencies, large quasi-government organizations), POE studies can provide feedback on occupant satisfaction, on building performance, and on operating costs and management practices. In sum, POE is a useful tool for improving buildings, increasing occupant comfort, and managing costs. So what mitigates against POE being a more universal activity? The barriers to widespread adoption of POE are cost, defending professional territory, time, and skills. Each one of these is examined briefly.

Cost

The cost barrier is not caused by the high costs of doing POE: building evaluation studies can be as expensive or as inexpensive as the resources available to finance them. The cost barrier is intrinsic to the

structure of the real estate industry, namely, who pays for POE? In commercial real estate circles, POE is not built into the architect’s fee, the construction bid, the move-in budget, or the operating budget of the building. This means that money to finance any POE activity, however small, must be found on a case-by-case basis.

Professional Territory

Defending professional territory is a barrier because POE is, after all, evaluation, and evaluation implies judgment. No active building professionals seek to have their work judged by outsiders as part of a process over which they have no control, even if the goal is a better understanding of a situation and not a performance review of a participant. It is necessary for POE to be seen as a useful a posteriori gathering of knowledge that is of value to the professionals involved, not as a critique of professional performance.

Time

The question of time is a mysterious one in commercial real estate. Every new building project has a rushed and constraining schedule, and every stage is carried out under unbending time pressures, although the reasons for this are not always clear at the time and in spite of the fact that rushed and fast-tracked projects often lead to costly change orders and bad long-term decisions. Going back for a follow-up look at a building, however, is not bound by the time pressures of new projects and, as a result, finds no place in the phases of a conventional building project.

Skills

Finally, what are POE skills and why is the lack of them a barrier? In spite of considerable reflection and writing by academics and researchers, there is no particular technique or tool associated with POE studies. The result is that the term itself has come to be applied to a wide range of different activities, ranging from precise cost-accounting evaluations to technical measurements of building performance to comprehensive surveys of user attitudes. Defining skills so broadly means that no one individual is likely to have all that are needed; it also means that POE does not fall into the skill set of any one individual or discipline and therefore tends to fall through the cracks.

In spite of the power of both the pros and cons of POE, the activity continues to be legitimized by one-off studies commissioned by large-scale owner-occupiers as well as by companies who, for one reason or another, are seeking to make more strategic real estate decisions. The term continues to have currency among academic researchers who are motivated to add to the general knowledge base about how buildings work after occupancy and how the environments they offer affect users. In the current context of new work patterns, changing office technology, and a more strategic approach to workspace planning, POE studies are finding a potentially valuable role in guiding companies toward more informed decision-making about office space.

CURRENT STATUS OF POE

POE has evolved from early efforts at environmental evaluation that focused on the housing needs of disadvantaged groups and efforts to improve environmental quality in government-subsidized housing. The idea that better living space could be designed by having better information from users drove environmental evaluation in Britain, France, Canada, and the United States during the 1960s and into the 1970s. It was only after the widespread acceptance of this logic—that finding out about users’ needs was a legitimate aim of building research—that other building types became targets for evaluation, namely, public buildings, including courthouses, prisons, and hospitals.

The building type most recently identified as a candidate for POE is office and commercial building design. Starting with the BOSTI study (Brill et al., 1985) linking features of the office environment to employee productivity, the corporate preoccupation with reducing space costs and improving productivity has caused the private sector to become more actively involved in POE. The challenge is to build POE into the cycle of corporate real estate decision-making so that professionals involved in building programming, design, construction, and operation can acquire the relevant tools and skills; so that provision for POE is built into either the operating or the capital budget; and so that the results of a POE feed into decision-making in a useful and constructive way.

In the following sections, four types of POE are identified. Each one is illustrated with at least one case study showing how it has been used. Although these four categories of POE are not exhaustive, they seem most useful for this overview. They are

-

building-behavior research, or the accumulation of knowledge;

-

feeding into pre-design programming;

-

strategic space planning; and

-

capital asset management.

At the end, the “best practices” that can be identified from this comparative analysis are summarized. Ultimately, the process of POE is seen as critical in terms of meeting the challenges identified above. In the last section, a functionally viable POE process is outlined.

Building-Behavior Research, or the Accumulation of Knowledge

The notion of POE as a routine activity of the real estate industry has not gained ground in Europe, where it remains an active area of applied research in most countries. At a seminar in Paris in 1992, French policymakers, public servants, and administrators were exposed to a rich panoply of North American POE research on public buildings in order to demonstrate the value of the approach and the increasing knowledge about buildings (Centre Scientifique et technique du bâtiment, 1993). In most European circles, the idea appears to be limited to individual academic researchers who carry out housing research,1 some office building studies,2 and public building POEs,3 as well as a growing number of hospital POEs in Sweden, Germany, and England (Dilani, 2000).

Funded by government agencies and using academically defensible research methods to study largely public building use, POE in Europe and Japan seems to be directed ultimately at building a broader and more reliable base of knowledge of human behavior in relation to the built environment, knowledge that may eventually come to be recognized as an academic discipline (environmental psychology, interior design?) but is not actively channeled to designers or other professionals in the real estate industry.

POE was identified as a component of the Project Delivery System used by Public Works Canada in the early 1980s, and was intended as a final stage in the programming, design, construction, and occupancy process of federal projects. A multidisciplinary approach to POE was developed and implemented for a short time in different federal office buildings in Canada (Public Works Canada, 1983). Precipitated by a concern with energy consumption in the early 1980s, studies were initiated of the performance of building systems, patterns of energy use in large buildings, and effects on occupants’ perceptions of comfort. These studies led to methods to devise effective but simplified data-gathering methods to provide reliable indicators of building quality (Ventre, 1988). The glue that bound these data-gathering and analysis efforts together was an analysis of user behavior and the links that could or could not be made with building operations.

A technique for assessing user comfort was one tool that emerged out of the Canadian effort and has since been widely implemented in private industry (Dillon and Vischer, 1988). An extensive survey of users was initiated in some eight government buildings in Canadian cities, and a major data analysis effort aimed to integrate the feedback from users with data collected from instruments measuring indoor air quality, thermal comfort, lighting and acoustic conditions, and energy performance. Analysis of the questionnaire results led to the conclusion that there are seven major conditions that affect users’ perceptions of their comfort in office buildings; each can be related to measures of performance of technical building systems, but not in direct or causal ways (Vischer, 1989).

The identification of what came to be known as the Building-In-Use measure of ambient environmental comfort led to the development of a standardized measurement tool in the form of a short questionnaire. The questions are formatted as 5-point scales on which building occupants rate the seven key dimensions of environmental comfort in their workplace. Both the five-year data-gathering and analysis effort that led up to the building-in-use system and its subsequent extensive use in the private sector can be considered a major POE initiative that has important implications for building-behavior research and has also generated a tool that can be used for other types of POE (Vischer, 1996).

Since its development for the Canadian government, the Building-In-Use (BIU) assessment system has been used all over the world. Two books in English and one in French, along with several articles, have been published that describe the system and its applications. A copy of the questionnaire is contained in Appendix C. Subsequent sections of this chapter deal with applica-

tions of this POE system in a variety of different contexts.

This year, a new research initiative in Quebec, Canada, has identified among other objectives the need to update and modernize the BIU assessment system. This objective is combined with another broad-ranging research goal, that of carrying out a POE of some 3,000 universal work-station installations in the offices of Quebec’s largest insurance company. Not only is this POE targeting ambient environmental conditions in the work environment, as was done in the 1980s, but it will also examine the psychological impact on individual and group work of a highly standardized work environment.

This study aims to make a valuable contribution to the office POE literature by adding to existing knowledge of building systems performance and human comfort. As well as updating our knowledge of key environmental conditions in the workplace, this research will measure psychological needs such as privacy and territoriality and the influences of group norms and membership as well as organizational values on occupant perception of the work environment. More purely social science methods are being used, such as individual interviews, focus groups, and a questionnaire survey to be carried out through individual interviews with a stratified random sample of the populations of up to six different buildings. Results will become available in the fall of 2001, and the study will be published in 2002.

Linking POE with Pre-Design Programming

One of the most appealing reasons to perform POE is to be able to inform building decision-making in the early stages of a new project. POE studies target user evaluation of an existing space where users are destined to occupy a new space that is being planned. Their feedback is needed to ensure that the new design meets users’ needs and solves problems in existing buildings. Certain public agencies such as the Division of Capital Planning and Operations in Massachusetts have POE as a legitimate and funded stage in all capital projects; the activity is run by the Office of Programming, the office responsible for all pre-design planning. The concept behind the legislation was to link POE with pre-design programming of public buildings.

In certain projects, the link has been effected and has paid off. For example, State Police stations are all designed along the same principles because they all serve the same functions. The Office of Programming developed a prototype concept that was built and occupied. The post-occupancy evaluation was part of the design process for new police stations, and the prototype was carefully examined in use, with its functionality, costs, structure, and materials evaluated. The prototype design was then modified, and the design of state police stations was standardized and built along the same lines. This saved time and effort on programming, design, and construction costs for the state. A similar approach has worked for child care centers and state vehicle repair and maintenance centers, and was being considered for state armories and firing ranges.

Soon after a large sum was approved by the Massachusetts legislature for a fast-tracked program of new prison construction, a post-occupancy prison study was carried out. The results of the new Old Colony state penitentiary POE were delivered to the Department of Corrections and ultimately used in programming four to six fast-tracked corrections projects by the Office of Programming.

However, in other projects, POE was not as successful. It was not uncommon for the budgeted amount for POE to be used up by change orders and other requirements of the construction process. These projects had no funds left for the POE stage of the process. In other cases, the time barrier alluded to above created a misalignment between POE studies and programming and design activities. For example, POEs of the correctional institutions built early in the fast-tracked process were not done because their results would not have been available in time to inform programming and design for the next project. A POE on a Massachusetts courthouse in 1985-1986 was only approximately aligned with the state’s courthouse construction program that was funded from 1984-1989.

POEs are still part of the public building programming process, and efforts have recently been made to develop and implement a standardized POE procedure that will fit in with the state’s building programs, provide the right information at the right time, and enable project managers to identify more exactly for each project the amount of money needed for POE.

POE was also built into government building delivery processes in New Zealand in the 1980s before the privatization of the public works department. Performing POEs facilitated pre-design programming and gave the design and construction team on each project a closer contact and understanding of users in each of its projects. This led to a design approach characterized by the designers as a negotiation, with multiple

exchanges of information and openness to change on both sides (Joiner and Ellis, 1989). However, this approach was threatened by the severe government cutbacks of the 1980s, closely followed by extensive privatization that put the public works departments in competition with private firms for public building projects. Although the close links with users that the public works department had developed gave it an edge, the time needed for negotiated design was not competitive, even though it could demonstrate that savings would be realized later on in the life of the building.

These accounts suggest that in spite of the logical imperative to link POE results to the front end of the design process, efforts to do so have had to struggle to survive. This should not be taken to mean that such efforts are futile; on the contrary, they are valiant and should be continued, if only to make us question the basic irrationality of the present building creation process.

POE in Strategic Space Planning

There is a clear difference between attempts to feed POE study results into pre-design decision-making on a routine basis, such as those described above, and using POE in strategic space planning. This latter use of POE has gained credibility in recent years as corporations are trying increasingly to provide functionally supportive workspace to their employees and simultaneously to reduce occupancy costs.

A number of companies in recent years have used Building-In-Use assessment to initiate a process of strategic space planning. This approach indicates a more complex situation than that which is characterized by conventional office space planning. It implies that the organization seeks to improve, innovate, or otherwise initiate workspace change to bring space use more in line with strategic business goals. These changes are not always understood or accepted by employees; thus, some companies have taken a change-management approach to new space design. Others have imposed major workspace changes in the same way as any other redesign of the workspace, sometimes with markedly negative results (Business Week, 1996).

One example of a company that used POE for strategic space planning in the early 1990s and has realized significant gains in corporate recruitment and retention, as well as increased sales, is Hypertherm Inc. (Zeisel, in press). This medium-sized manufacturing company located in New Hampshire is a world leader in the design and production of plasma metal-cutting equipment. As a result of a need for expansion of both its manufacturing plant and its offices, Hypertherm hired an architect whose drawings and conceptual approach it later rejected on the grounds that a new work environment should accompany the significant organizational change that was needed to prepare the company for global expansion and a better competitive position as its share of the world market grew.

The workspace design process at Hypertherm included a POE of the existing space. As well as providing useful data to help design the new space, the survey caused employees to feel both consulted and involved in the process of designing new space that would meet business goals. The strategic space planning comprised a number of different steps. First, a shared vision of the new work environment was created through a structured team walk-through of the existing facility. The management team and consultants toured the facility as a group, discussing the tasks of each work group, pointing out difficulties and advantages with the present space, and commenting on each other’s presentations. Recorded on cassette tape and transcribed, the tour commentary was presented back to the client, along with a comprehensive set of photographs, to document existing conditions. This activity involved all members of the team and gave the consultant a large amount of information efficiently; consensus began to build on what needed to be done to solve the company’s space problems.

A subsequent series of facilitated work sessions enabled the management team to generate a set of goals and objectives not only for the new space but also for the restructured organization. This stage yielded a set of design guidelines to be applied to the new design and established priorities as to the relative importance of what the team wanted to achieve. Most importantly for the future of the process, it resulted in consensus.

The next step required involving employees in the design process in order to ensure widespread acceptance of the vision. The BIU assessment survey of employee perceptions of the physical conditions of the existing building started the process of employee involvement. Each employee filled out the survey and was therefore alerted to the imminent new space design process and to the importance of his or her role in it. The survey results were published in the company newsletter and showed the best and the worst aspects of working in the old space.

A final step in the strategic approach was to invite employee representatives to provide feedback on design development and to communicate key design decisions to their colleagues.

The questionnaire survey was distributed a second time, about six months after move-in, to compare levels of user comfort between the old and the new buildings. Not only were occupants pleased with their new space, but the process of buy-in and participation also helped them understand from day one how it would work. They accepted it without the discomfort and resistance often exhibited in new work environments, because they knew exactly what to expect. The employees took ownership of their new space because they had been involved in decision-making throughout.

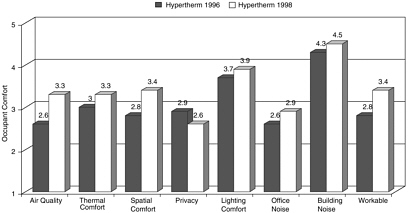

Figure 3-1 shows employee ratings on the seven dimensions of workspace comfort in the old building and after the renovation. Having a short, standardized questionnaire to compare employee perceptions before and after a workspace change is a significant tool for POE studies. BIU assessment has been used successfully in strategic space planning for a range of companies, including Bell Sygma, Reuters, Boston Financial Group, and GTE Government Systems.

Capital Asset Management

Using POE as a tool for managing building assets is not new, but it has not been widely implemented. This is perhaps due to the diverging focus of the two activities. Asset management tends to rely on data on building operating costs, maintenance and repair needs, real estate value and market conditions, and tenant improvements. The standard POE approach provides data on user perceptions and attitudes through group feedback sessions, such as focus groups, survey questionnaires, and in-situ observations of user behavior. As a result, feedback from employees in corporations is often considered to be of interest more to human resources departments than to the real estate team.

However, an approach to POE that combines assessment of the physical condition of the building and building systems with user comfort assessment on such topics as indoor air quality and ventilation rates, lighting levels and contrast conditions, building (not occupant) noise levels, and indoor temperature (thermal comfort) could constitute another tool to add to those used in conventional asset management. One weakness in making this potentially fruitful link is the finding that much of the literature that has been published on specific building studies has been unable to demonstrate systematic links between the feedback users provide through questioning and data derived from instrument measures of interior building conditions (Vischer, 1993). Moreover, portfolio managers tend to steer away from POE approaches because there are few tools available (the BIU assessment questionnaire being one of the few simple ways of collecting user

FIGURE 3-1 Before and after BIU profile comparison.

feedback on a standardized basis) and because any questioning of users requires informing and involving tenants. A more finely tuned and precise approach to POE is necessary in order to make this approach valuable to professional evaluators and asset managers in organizations.

However, BIU assessment has been used by large owner-occupier corporations to collect data on user perceptions and link these directly with ambient interior conditions and, therefore, building performance and building quality. Two examples of companies with extensive real estate holdings who attempted to use POE systematically as an asset management tool are Bell Canada and the World Bank. Both organizations owned some and leased some of their office space; both were committed to providing high-quality office space, in the first case, as part of a continuous improvement philosophy and in the second case, as part of the corporate mission; and both chose BIU assessment as their POE tool for managing assets.

In both cases, BIU surveys were carried out in almost all of their buildings, in both leased and owner-occupied space. In the case of Bell, this meant surveys of 2,500 people distributed in its headquarters tower in Montreal, in suburban office buildings in Montreal and Toronto, and in one building in Quebec City. In the case of the World Bank, this meant surveying 2,800 employees distributed in the eight leased and owned buildings it occupied in Washington, D.C., and also included one building in Paris.

Both corporations collected large amounts of feedback from occupants using the BIU questionnaire. In addition to individual building analysis, the BIU data on environmental comfort were grouped and analyzed for overall trends in occupant comfort. The large number of cases and variety of building settings surveyed enabled baseline scores to be calculated on the seven comfort dimensions across all buildings. This, in turn, allowed real estate staff to identify which buildings or parts of buildings exceeded the baseline scores and which fell below them. Both organizations found that this approach was cost-effective and not data heavy, did not consume inappropriate amounts of staff time, and provided a single-digit indicator of environmental quality. BIU results from individual buildings could easily be compared either to their own baseline, that is, the standards set by their own building stock, or to the baseline scores generated by the pre-existing BIU database, indicating a generalized North American standard of quality based on survey results from some 60 buildings.

Procedures were set in place to allow the baseline scores to be updated as new information was added through additional building surveys. One organization, Intelsat, initiated an electronic form of the questionnaire survey in order to be able to update occupant comfort ratings easily. In the case of the World Bank, an effort was made to link the BIU database to computerized drawings that were used to plan and update office layouts, so that BIU scores of buildings, floors, or areas of floors that were slated for reconfiguration could be consulted and indices of quality made available as part of the space planning process—a sort of instant POE.

BEST PRACTICES

The rapid overview of case studies presented above offers the following conclusions. First, it is clear that POEs of built environments must continue in order to enhance our knowledge about the effects of physical space on people. The challenge of the “building-behavior research” definition of POE is to ensure that the knowledge gained from research studies is not only disseminated in the academic community but also successfully transferred to the world of designers, builders, and financiers of real estate.

For public agencies or other organizations that repeatedly construct the same building type, linking POE with pre-design programming can save money and time. Evidence indicates, however, that even when the link to pre-design decision-making is recognized, POE is not simple to implement. It is likely to be successful only if, as Friedman et al. (1979) pointed out in their seminal first book on building evaluation, a structure-process approach is used. This means designing an approach ahead of time, developing and testing the process beforehand, and ensuring that resources continue to be available.

POE is also a potentially useful tool for asset management, as long as the approach employed to collect feedback from users can be effectively integrated with the other more market-oriented data-gathering efforts of asset managers. This may mean simplifying the elaborate social science approach favored by researchers and investing in a test initiative to implement and test an asset management approach to POE in the context of the real estate industry so as to demonstrate how feedback from users can both be collected easily and enhance real estate decision-making.

POE also seems to have a natural place in strategic space planning and could be developed for use by a

wide variety of organizations. The key to this application is to consider POE a tool for involving building users in planning new workspace. Some organizations have reservations about allowing their employees to become too involved in the emotional and time-consuming planning of their new space. However, techniques exist for managed participation that have been successful in a variety of instances in helping to control the amount and type of user involvement. Involving users in new workspace planning is necessary for any successful change initiative, and POE is one of the tools available to this end.

Finally, in spite of the ground-breaking efforts by some large organizations to build POE techniques into their building management activities, it is curious that large property management firms are rarely known to use POEs for building diagnostic purposes or for improving services to tenants. Some property management companies content themselves with short satisfaction questionnaires that tenants complete following a repair or move. However, in the experience of this writer, property management firms, along with large banks and financial institutions, are the companies least likely to perform POE. Techniques of POE need to be developed for use by organizations that would make good use of occupant feedback if they had a simple, reliable way of getting it. These techniques would help them to build environmental evaluation into their planning, budgeting, and maintenance cycles.

It should be noted that some companies fear soliciting feedback from building occupants on the grounds that both seeking and receiving this type of information may obligate them as building owners and/or managers to make a costly change to their services or to the building itself. At least one lawsuit has been heard of, resulting from a perceived lack of follow-up to an occupant survey that questioned users about their perceptions of indoor air quality and lighting (Boston Globe, 1987).

MANAGING POE INFORMATION

Once POE exists outside the protected framework of a case study research project, another set of barriers present themselves in the form of dissemination of the information yielded by the study. As long as the POE is carried out as academic research, the sanctioned forms of academic research dissemination are available (publication in journals, conferences, etc.). However, in the practical world of building design, construction, and management, most organizations have no established system for knowing how to process, direct, and act on the information they receive from a POE. This may cause the information not to go anywhere, and it becomes a reminder to decision-makers not to repeat the experience. Having no clear use for the information may generate conflict and resentment among those who are expected to act on it; seeing their feedback ignored and not put to good use may alienate building occupants.

Many organizations that initiate POE are unclear as to why they want the information, what information they want, to whom it should go, and how they are expected to follow up on it. Several organizations familiar to the author have explicitly required that the results—whether positive or not—of a POE survey not be disseminated.

Among the range of possible reasons for a lack of planning for the dissemination of POE information are the following:

-

“usefulness” of user surveys,

-

complexity of the design process,

-

negativity of the comments received, and

-

complexity of managing information.

Each of these is discussed below.

Usefulness of User Surveys

Questioning people about how much they like or dislike as space that they occupy inevitably obliges the researcher to confront the “so-what?” question: So what if some users like a feature and others do not? The notion of liking something is so subjective and constrained by circumstances that it is difficult to extract generic information or to generalize from users’ responses. However the notion of user satisfaction is at the base of almost all POE approaches, leading to highly specific results from POE case studies and a lack of generalizable conclusions to guide additional research or changes in design (Vischer, 1985).

Some POE approaches—for example, BIU assessment—have replaced the emphasis on user satisfaction with questions that target a more functional evaluation of the work environment. BIU survey questions, for example, ask respondents to identify their level of comfort in relation to the specific tasks of their job. The intent is to shift the user feedback away from personal likes and dislikes toward what might be called an “objective” assessment of the functionality of the work

environment. For example, lighting quality is rated according to the respondent’s task requirements: work at a computer screen, reading print-out or other documents, or appraising forms, colors, and other visually oriented tasks. This approach is based on the concept of “functional comfort”; theoretically, any building user can evaluate functional comfort for any other person performing the same tasks in the same environment.

Organizations that have asked, “Do you like or dislike … ?” or “Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with … ?” have found the results too subjective to be useful. Managers fear that these questions raise users’ expectations and cause them to expect wide-ranging corrective measures and/or gratification of their wishes. Although some POE studies target correcting problems in the building, many are initiated without a budget or a procedure for follow-up. Moreover, companies often design questionnaires with little regard to the considerations necessary for good survey design. Often such questionnaires are overly long and detailed, and analysis of the results is almost always limited to simple frequencies and percentage calculations. As a result, companies find the data less than useful and conclude that occupant surveys are a waste of time.

Complexity of the Design Process

People who are trained in and perform building design have difficulty moving beyond design into a POE once their buildings are occupied and built. Some designers evince a general curiosity that generates some unfocused evaluation activity that gives them a sense of the success of their design decisions. The feedback that the designer acquires rarely goes further than the individual seeking the information. Some designers will spend considerable time on acquiring feedback, whereas others have almost no curiosity, and most are somewhere in between. Why are design professionals not more curious to learn from the positive and negative impacts of their design decisions? I believe the answer to the question is the complexity of the design process, for the following reasons.

The approach of nondesigners to POE is somewhat different from that of designers: the former approach space as another cultural artifact to be studied using traditional social science methods. Some studies seek to orient the space evaluation to the basic design decisions and/or criteria. In the words of Inquiry by Design (Zeisel, 1975), each design decision is a hypothesis for research. Other researchers have taken architects’ decisions as hypotheses and tested them with POE data (Cooper, 1973). This approach implies a linear logic according to which programming (pre-design information gathering) leads to design decisions, which lead to construction of what has been designed, which in turn leads to POE. Montgomery elaborates on this linear logic in his introduction to Architects’ People (Ellis and Cuff, 1989). As he points out, this may be a model for a rational world, but it is all too clear that the world of architecture and real estate is anything but rational, that design itself is not rational, and that trying systematically to link POE with design for those involved in that process is all but impossible.

What researchers are less aware of, and the designer is painfully aware of, is the irrational nature of design decisions. Each design decision on a project is influenced by the personality traits, role and status, and personal opinions of the individuals involved (client, project manager, architect, contractor, etc.) as well as by the stage reached at the time of making the decision, how involved and informed users are, expectations, budget, and other pressures such as government regulations, site constraints, and so forth. The designer’s own design ideas, and how these are communicated, when and to whom, also affect the process. These are but a few of the factors that mean that building design is not controlled by any one person or agency and that therefore a clear notion of a project’s design ideas and intentions for the purpose of POE is difficult to identify.

The author’s own experience of highly participatory design processes has provided first-hand experience of the convoluted, political, and anything-but-linear decision-making process that causes a building to be what it ultimately is. In many cases, no amount of rational planning and programming can change the likelihood that once occupied, the use of the space begins immediately to change. Sometimes small adjustments are made creating incremental change over time, and sometimes the basic assumptions that guided the design of the building are dramatically forgotten and the space is adapted to serve a different purpose.

Given the nature of building design and construction processes, it is unrealistic to expect a designer to seek out feedback on the long-term effectiveness of design decisions on a systematic basis. However, this is more of a comment on the POE process than on the POE product, a product whose usefulness cannot be denied in spite of the complexity of the decisions that go into the creation of new physical environments.

Primarily Negative Feedback

Because of the emphasis on building user feedback, much of the information received from POEs is critical in nature and appears to assign inordinate weight to nonfunctional or dysfunctional aspects of a building with little mention of what works. This impression, although false, makes it difficult for information to be shared in a constructive and useful way. The best way around this dilemma is for a skilled POE researcher to weigh the importance of the information received.

For example, 10 comments from building users about dripping soap dishes in bathrooms, slippery front steps, and dust on the work surface cannot be compared in importance to one or two comments about poor lighting or a lack of meeting rooms. The former are irritants; they should not carry the weight of an item that creates a serious dysfunctionality or impedes user effectiveness. Similarly, it has frequently been this author’s experience during focus group sessions with users to listen to 45 minutes of complaints and negative criticism about their space only to have them comment (once they have got all this off their chests) that they like the daylight and view from the windows, the space is much better than where they used to work, and they like working in the building!

One of the challenges of POEs going forward is to identify a reasonable system of informed weighting of user feedback so that the data received can be interpreted according to balanced positive and negative categories.

Complexity of Managing POE Information

The information that results from POE is directed in a number of different directions. In some cases, solutions are sought to problems that have been identified in a building, and the information is directed to facility managers, building owners, and landlords. In others, the information is directed to designers to help them make better design decisions on a specific project or generically with regard to a building type. In some cases, building users are informed regarding the results of a POE in which they were involved, as a way of involving them in planning change and finding ways of improving the environment. In yet other cases, the information is seen as valuable in itself and disseminated to researchers seeking to understand more about the person-environment relationship. Finally, information about building systems performance, occupant functional comfort, operating costs, and adaptation and re-use is directed to stakeholders in the planning, design, construction, and occupancy process who are in a position to make decisions about future building projects.

For each of these, and no doubt other, applications of POE information, some thought needs to be given at the outset to collecting and presenting POE information in a way that suits the receiver and consumer of that information. This means that a clear understanding of the context is necessary and that the POE process should be designed as a function of contextual constraints. Key questions to be asked before any POE study include the following: Who wants the POE? How do they want to use the information? What resources are available to gather, analyze, and disseminate the information? Who will receive the results, and when? What expectations do stakeholders have of the POE results?

THE FUTURE OF POE: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR AN UNOBTRUSIVE POE PROCESS

The importance of the process used in carrying out a POE cannot be underestimated; in this author’s opinion it is more important than the method selected and the data gathered. Once users are involved—as they are once they are questioned about their use and occupancy of a building—how they are approached, what information they are given, and the follow-up they experience are all critical stages in the development of the relationship between the occupant and his physical environment. The POE, then, provides an opportunity for improvement not only of the building and of the environment it provides to its users, but also of the way users perceive and feel about their territory.

Ideally, one would like to see POE carried out systematically on a wide variety of types of building, but not before clear objectives and results are identified. At the outset, it is important to clarify the value that the POE will have for the person or agency carrying it out. If one can identify that the POE has value in the context in which it is being implemented, then decisions about financing it, identifying the right things to be studied, and disseminating the results and information to the right people will follow. As the examples in this chapter show, stakeholders in private sector real estate development fail to attach value to POE, and even public agencies—for which the value of POE is apparent—

find that the complexities of the process outweigh potential gains from POE.

In conclusion, it is proposed that a workable POE process designed to succeed outside academic circles incorporate the following steps:

-

A simple, reliable and standardized way should be developed of collecting useful feedback from occupants, not on the entirety of their experience of using the building, but on a few, carefully selected and identified indicators of environmental quality.

-

The indicators selected for measurement should be decided beforehand according to that which is most relevant to the initiators of the POE and the context in which it is implemented.

-

It is necessary to clarify at the outset who are likely to be the consumers of POE results and therefore how best to communicate these results to them.

-

Consideration should be given to POE techniques that avoid direct questioning of users—for example, using instruments, observations, expert walk-throughs, etc.—as well as to refining social science techniques to devise reliable and rapid ways of questioning building occupants.

-

Efforts to combine instrument data collection and surveys of building users can be costly, because large amounts of data are generated without yielding much additional useful information. One approach is to use the analysis of user responses to indicate where and when follow-up instrument measures might clarify the nature of the problems identified and indicate possible solutions.

-

Users should be well informed regarding the purpose of their involvement is providing feedback and should be made aware in situations where immediate correction of problems is not envisioned. In fact, it is necessary to recognize that building users can be “measuring instruments” of environmental quality, rather than only customers to be served.

-

A decision should be taken at the outset as to whether or not user survey results will be made available to building occupants and, if so, in how much detail and for what purpose.

-

Resources for carrying out the POE should be defined clearly so that data collection and analysis activities fit into time and budget constraints, however modest.

-

If a questionnaire is given to occupants, it should be designed and analyzed by someone knowledgeable in survey research, even if this person is not involved in the eventual use and application of the results.

-

A standardized approach that allows building professionals (designers, developers, managers) to collect modest amounts of comparable data from a variety of buildings to analyze on a comparative basis is likely to be more useful than a detailed one-off case study in most situations.

-

Public agencies should examine the possibility of setting up test POEs on a demonstration basis, to develop POE techniques, to demonstrate value, and to determine the best ways of making POE relevant to the building industry.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jacqueline Vischer is an environmental psychologist. She is currently professor and director of the interior design program at the University of Montreal. She has consulting experience in architecture and planning projects in the United States and Canada. As principal in her own consulting firm in Vancouver, Canada, Dr. Vischer and her staff undertook contract research from government agencies in residential planning and evaluation, institutional programming, and policy analysis. Dr. Vischer then spent five years developing building performance studies of office buildings for Public Works Canada in Ottawa, projects from which the building-in-use assessment system emerged. She then undertook the design and implementation of a post-occupancy evaluation program for public buildings owned and operated by the State of Massachusetts’ Division of Capital Planning. In 1989 Dr. Vischer started the Institute For Building Science, which became Buildings-In-Use in 1990 and opened its Montreal office, Bâtiments-en-Usage, in 1991. Dr. Vischer has held positions as lecturer and instructor at the McGill University School of Urban Planning, University of British Columbia, and Harvard University’s School of Design. She is a member of the Environmental Design Research Association, the American Society for Heating Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Engineers, the Montréal Metropolitan Energy Forum, and the International Facilities Management Association. Dr. Vischer holds a bachelor of arts in psychology from the University of California, Berkeley, and a master of arts in psychology from the

University of Wales Institute of Science and Technology, and a Ph.D. in architecture from the University of California, Berkeley.

REFERENCES

Boston Globe. (1987). 30 June.

Brill, M., Margulis, S.M., and Konar, E. (1985). Using Office Design to Increase Productivity (2 vols.). Buffalo, N.Y.: BOSTI and Westinghouse Furniture Systems.

Business Week. The new workplace. (1996). April 29, pp.107-117.

Centre scientifique et technique du bâtiment (1990). Améliorer l’architecture et la vie quotidienne dans les bâtiments publics. Paris: Plan construction et architecture, Ministère des équipements, du logement, des transports et de l’espace.

Cooper, C. (1973). Comparison Between Architects’ Intentions and Residents’ Reactions, Saint Francis Place San Francisco. Berkeley, Calif: Center for Environmental Structure.

Dilani, A. (ed.) (2000). Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Health and Design. Stockholm: University of Stockholm.

Dillon, R. and Vischer, J. (1988). The Building in-Use Assessment Methodology (2 volumes). Ottawa: Public Works Canada.

Ellis, W.R, and Cuff, D. (1989). Architects’ People. New York: Oxford University Press.

Farbstein, J., and Kantrowitz, M. (1989). Post-occupancy evaluation and organizational development: the experience of the United States Postal Service. In: Building Evaluation. Preiser, W. (ed.). New York: Plenum Press, p. 327.

Friedman, A., Zimring, C., and Zube, E. (1979). Environmental Design Evaluation. New York: Plenum Press.

Joiner, D., and Ellis, P. (1989). Making POE work in an organization. In: Preiser, W. (ed.) Building Evaluation. New York: Plenum Press, p. 299.

Marans, R., and Spreckelmeyer, K. (1981). Evaluating Built Environments: A Behavioral Approach. University of Michigan, Survey Research Center and Architectural Research Laboratory.

Public Works Canada (1983). Stage One in the Development of Total Building Performance (12 volumes). Ottawa: Public Works Canada, Architectural and Building Sciences.

Ventre, F. (1988). Sampling building performance. Paper presented at Facilities 2000 Symposium, Grand Rapids, Mich.

Vischer, J. (1985). The adaptation and control model of user needs in housing. Journal of Environmental Psychology 5:287-298.

Vischer, J. (1989). Environmental Quality in Offices. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Vischer, J. (1993). Using occupancy feedback to monitor indoor air quality. ASHRAE Transactions 99 (Pt.2).

Vischer, J. (1996). Workspace Strategies: Environment as a Tool for Work. New York: Chapman and Hall.

Zeisel, J. (1975). Inquiry by Design. New York: Brooks-Cole.

Zeisel, J. (in press). Inquiry by Design, 2nd edition. New York: Cambridge University Press.