Health Risk Considerations for the Use of Unencapsulated Steel Slag (2023)

Chapter: 3 Properties and Environmental Dynamics of Slag

3

Properties and Environmental Dynamics of Slag

The previous chapter covered the formation of liquid slag as part of electric arc furnace (EAF) steelmaking and its complex and highly variable chemistry. This chapter discusses the chemical and physical properties of slag in its solidified state, trace elements in slag, changes in slag due to weathering and wear, and the potential release and environmental transport of slag chemicals of potential concern (COPCs).

Thus to understand the solidification process of these slags during cooling, one must have a clear understanding of the starting chemistry, the cooling rate, and the amount of time that the slag exists at elevated temperatures. Additionally, slag can react with carbon dioxide, oxygen, and water vapor; thus, the local conditions and time of processing of the slag are important in understanding the mineralogy and physical properties of EAF slags, which might be applied for unencapsulated uses, such as landscaping.

MINERALOGY AND MINERALOGICAL PHASES OF SLAG SOLIDIFICATION

Slags are neither internally uniform nor collectively uniform from process to process, nor are they uniform from heat to heat. The composition of the slag produced is set in response to the variable loadings of scrap ingredients, fluxes, refining and alloying reagents, and technology requirements. The same considerations apply to the ladle slags that are formed by further refining of EAF liquid steel. What steel was made, what was the feedstock liquid steel from the EAF, and what fluxes and reagents were used? These are the questions that affect the variations in slag constitution from heat to heat. The additional considerations of processing and cooling history drive the mineralogical variations found within different parts of the same batch.

This section reviews the mineralogical constitution of the various sorts of solidified slags produced by EAF steelmaking. “Mineralogical” is used in the sense of solid material. Even though slag solids may or may not occur in nature (a required condition for mineral status), the individual constituent grains may have the ordered atomic arrangement and definite chemical range in composition of natural minerals. For example, iron carbide (Fe3C) is known to the steel industry as cementite, but when it is found in meteorites of natural origin, it is called cohenite. The mineralogy of ferrous slag has shifted somewhat over time as steelmaking has shifted from primary production of pig iron from ore in a blast furnace followed by use of a basic oxygen furnace (BOF), and now to steel production by recycling of scrap steel in EAFs. Slags from blast furnaces used to produce iron and slags from BOFs and EAFs for steelmaking are ferrous slags. It is possible that slag composition will be shifted by future choices of alternate fuels in the steelmaking process. The economic and sustainability aspects of waste stream management drive the use of wastes as fuels. For instance, if hazardous halogenated liquid wastes were to supplement natural gas, coke, or carbide to maintain process temperature or promote slag foaming, the character and toxic balance of slag and associated dust may change.

Slag mineralogy further evolves through exposure to moisture, carbon dioxide (CO2), and the oxidizing weathering environment. It is important to understand slag mineralogy because the minerals themselves are the individual constitutive elements of the potential hazard and utility matrix presented by slags for unencapsulated uses (such as loose ground cover).

Minerals are the resources, but mineral particles can also be dangerous to public health, especially particles with diameters of 2.5 micrometers (μm) or less, which are small enough to move deeply into the respiratory tract and lungs of humans. Part of understanding slag toxicity includes understanding the particle size range of the mechanical degradation products of its minerals. The formation of respirable-sized particles is set by such properties as mineral hardness and cleavage. Such shards pose a hazard for cilial

damage in the respiratory tract even if not deeply respirable into alveoli. Mineral bulk chemistry also plays a role in determining slag toxicity (see Box 3-1).

Solidification of molten slag from EAF steelmaking begins at very high temperatures (~1,600 °C) in a largely liquid state, leading to the possibility that the crystallization to minerals during cooling might be guided by the near-equilibrium, high-temperature thermochemistry of the chemical ingredients involved: FeO, CaO, MgO, Al2O3, Fe2O3 (ferric oxide), and SiO2 and minor constituents, such as manganese (Mn), vanadium (V), chromium (Cr), and titanium (Ti). Slag mineralogy roughly conforms to the thermochemical dictates of phase equilibrium (see Appendix E). If cooling is slow, quasi-equilibrium crystallization is more likely to follow the thermochemical constraints. If solidification is facilitated by water-assisted quenching, much glass recovery can occur instead of the formation of crystalline minerals, especially in siliceous slags. This expectation is directly conditioned by the observation of the solidification of natural volcanic rocks of various sorts when they are erupted under water rather than in air.

The extent to which crystallization proceeds, or to which the solidification product is glass, depends on both the slag composition and the cooling rate. The issue of crystallization versus solidification to glass is important to the leaching and weathering profiles of the slag. Glasses tend to liberate their constituents more readily than do crystalline slag minerals. Deviations from equilibrium crystallization are expected when glass forms. Furthermore, several of the phases that do crystallize are in reaction with liquid slag and should disappear with falling temperature, and yet they are preserved in the solidification product. This preservation is a clear indication that equilibrium crystallization is not strictly followed. In addition, for both lime (CaO) and silica (SiO2), the thermochemical landscape is such that they should never be found in the same slag if equilibrium were maintained. There are many intermediate compounds of exceptional stability that preclude a lime–silica pair from representing an equilibrium crystallization assemblage. Yet they are occasionally found in the same slag.

This apparent contradiction can be understood when looking at the timescale over which an equilibrium can be maintained during processing at some temperature (T) for some time (t). If solid ingredients contributing to a mix are in chunks too large to fully react with the other ingredients in the mix, the starting materials may be partially preserved and only partially digested into a quasi-equilibrium slurry of reactants and intermediate products. This scenario is supported by the documentation by Yildirim and Prezzi (2011), showing centimeter-scale nuggets of undigested lime, or “lime pockets,” in a BOF slag surrounded by a brown reaction rind; see Figure 3-1. These nuggets are the calcined dolomitic limestone upper blanket chunks that were too large and too refractory to be consumed by the liquid in the processing T-t available during slag dumping. That consumption is in progress is indicated by the brown rind surrounding the pocket. One should expect local compositional heterogeneity vectors within slags, reflected in the mineralogy of the local crystallization products. Incomplete, constrained mass transfer was in progress between the chemically incompatible materials on either side of the interface before cooling slowed all such digestion processes.

SOURCE: Yildirim and Prezzi (2011, Fig. 4).

Given that there are departures from strict tracking of slag crystallization from equilibrium thermochemistry, it is of interest to note the greater conformities. The list of minerals found in slags includes those found in the primary phase fields of the equilibrium thermochemical liquidus diagrams reviewed in Appendix E. The list of slag minerals is a long one because the use of basic carbonates (calcite, dolomite) alone as a melting flux would not be successful because the decarbonated oxides, lime and periclase, are extraordinarily refractory. They must be combined with some additional oxides to make a lower-melting-point flux. The usual choices are SiO2 and Al2O3 sourced from the aluminosilicate clay residue in impure limestone, from coal/coke ash or from admixed quartz sand or ground quartzite, from olivine (Mg,Fe)2SiO4, or from serpentine, which dehydrates to olivine and siliceous material.

TRACE CONSTITUENTS IN SLAG

Minor and Trace Inorganic Elements

As with the major elements in slag, the abundance of minor and trace elements present in slags depends on a range of factors associated with production, including processing temperature, cooling rate, gas composition, and composition and impurities in feed materials (Piatak et al., 2021). A compilation from the literature of slag analyses, including different types of ferrous and non-ferrous slags from sites worldwide, was published by Piatak et al. (2015) and updated by Piatak et al. (2021). This comprehensive compilation provides an overview of the range of major, minor, and trace element concentrations found in all types of slag. In this report, we focus on their compiled data for EAF and ferrous slags. Table 3-1 reproduces data for EAF slags only reported in Piatak et al. (2021). Mn is the most abundant minor element that is a COPC, averaging around 4 percent by weight as MnO in slags but has been reported as high as 15.6 weight percent MnO. The average MnO concentration in EAF slags is similar to that of other types of ferrous slags, such as BOF slags, and slags from steel and legacy sites (Piatak et al., 2021). As mentioned in Chapter 2, the range for MnO suggests there was co-mingling of the EAF slag samples with ladle slag samples, as low values of MnO are not normal in an EAF slag. However, the average values for the majority of the samples were EAF slag alone. Piatak et al.’s compilation of chemical analysis indicates the complete EAF slag chemistry where all materials that can form a stable oxide during oxidation are found in the slag.

TABLE 3-1 Ranges and Averages of Minor and Trace Elements of EAF Slags

| Weight (in percent) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Maximum | Average | Standard Deviation | Number of Samples | Number of Studies | |

| Mn (as MnO) | 0.4 | 15.58 | 4.4 | 2.9 | 34 | 17 |

| mg/kg | ||||||

| As | 0.5 | 7.12 | 4.3 | 2.3 | 7 | 3 |

| Ba | 160 | 3,600 | 1,195 | 1,169 | 10 | 5 |

| Cd | 0.1 | 19 | 4 | 7.2 | 7 | 3 |

| Co | 2.32 | 11 | 5.4 | 2.8 | 10 | 4 |

| Cr | 320 | 200,000 | 16,873 | 38,920 | 25 | 12 |

| Cu | 62 | 540 | 197 | 116 | 12 | 5 |

| Ni | 0.07 | 3,180 | 298 | 833 | 14 | 6 |

| P | 100 | 5,400 | 2,161 | 1,575 | 21 | 12 |

| Pb | 2.9 | 3,000 | 533 | 1,065 | 10 | 5 |

| Sb | 1.09 | 18 | 5.2 | 7.2 | 5 | 2 |

| Sn | 3.2 | 34 | 17.5 | 10.4 | 6 | 3 |

| V | 170 | 1,710 | 873 | 555 | 18 | 8 |

| Zn | 31 | 6,800 | 648 | 1,718 | 15 | 8 |

SOURCE: Compiled from Piatak et al. (2021).

Trace element compositions are variable within and among slag types. In order to evaluate relative enrichment levels in slags, Piatak et al. (2021) compared trace element concentrations to regional soil screening levels for site remediation for either residential or industrial use.1 A screening level is a generic, risk-based concentration of a contaminant that is used to help identify sites or conditions that may require

___________________

1 See https://www.epa.gov/risk/regional-screening-levels-rsls-generic-tables.

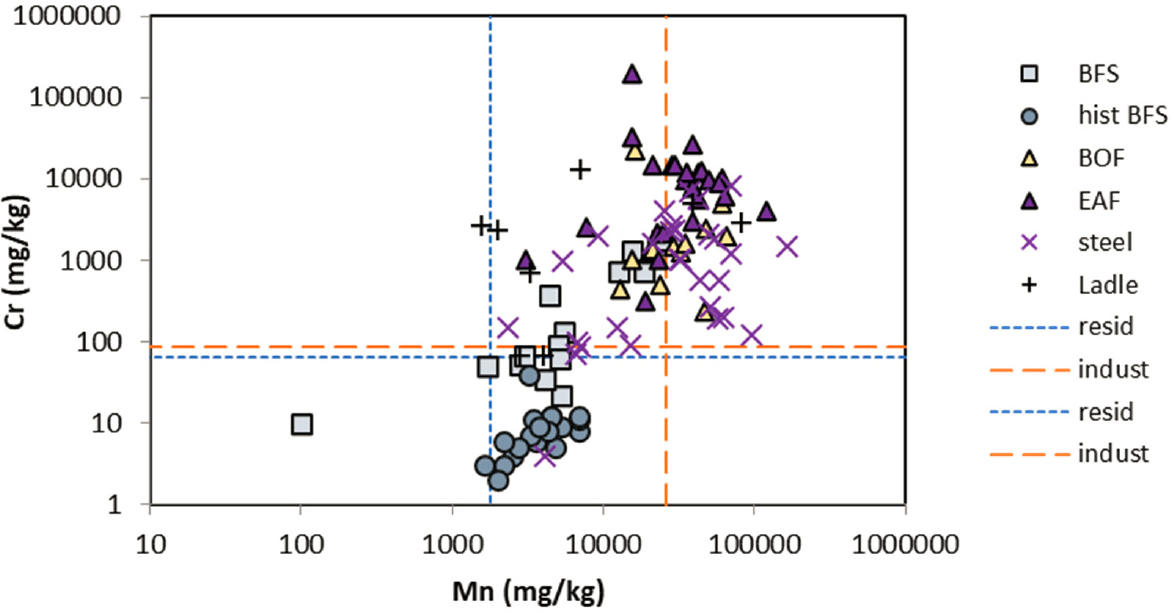

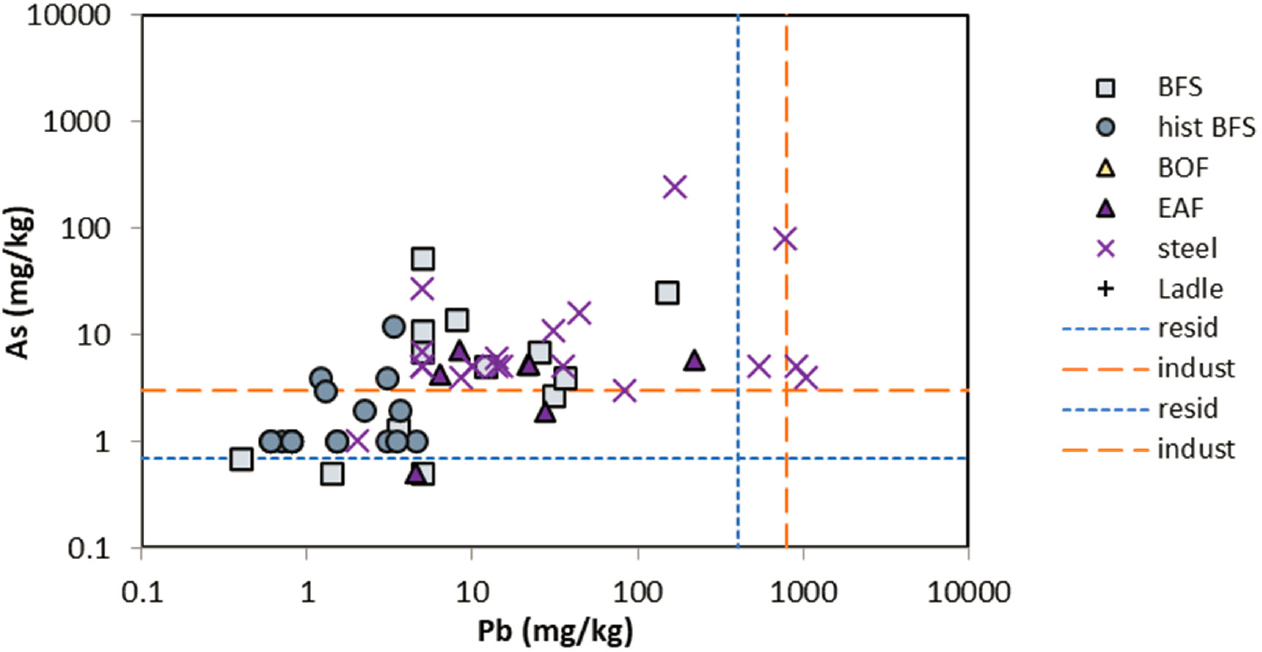

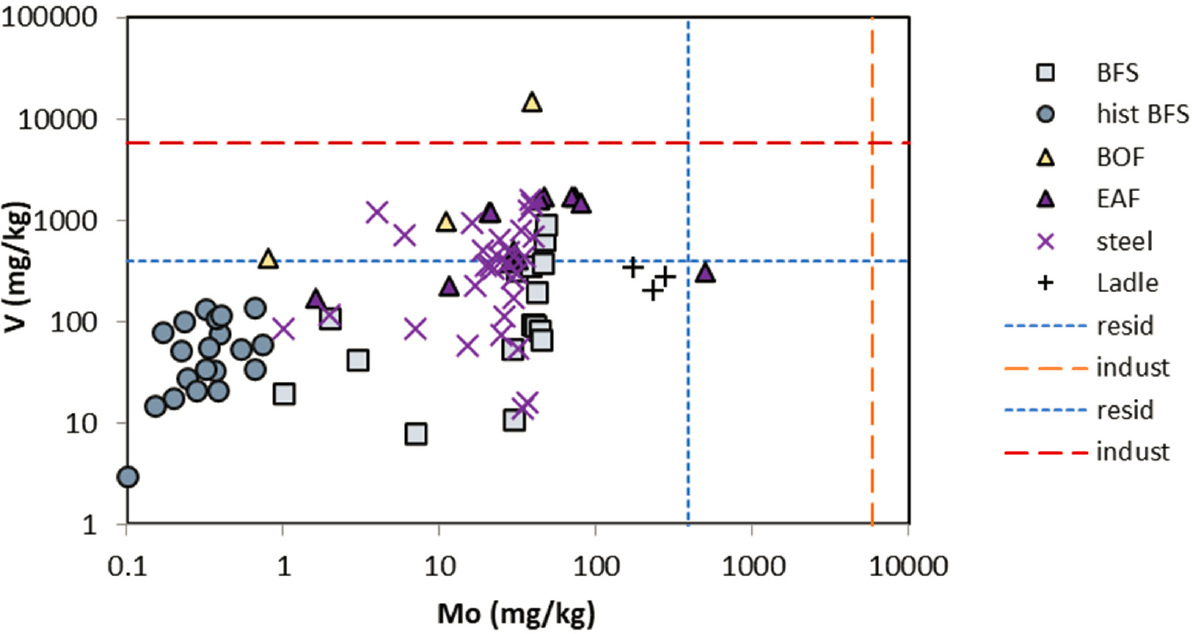

further evaluation of potential risk. The screening levels used were from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) guidelines for all elements, except for total Cr, which was taken from Canadian guidelines by Piatak et al. (2021) (EPA soil screening levels are specific for Cr3+ and Cr6+ rather than total Cr). Elemental data for EAF slags and data for other ferrous slags for comparison are shown in Figures 3-2a, 3-2b, and 3-2c.

NOTE: Residential (blue) and industrial (red) soil screening levels are shown as dashed lines.

SOURCE: Replotted from Piatak et al. (2021, Fig. 3.4).

NOTE: Residential (blue) and industrial (red) soil screening levels are shown as dashed lines.

SOURCE: Replotted from Piatak et al. (2021, Fig. 3.4).

NOTE: Residential (blue) and industrial (red) soil screening levels are shown as dashed lines.

SOURCE: Replotted from Piatak et al. (2021, Fig. 3.4 for V; Mo data from the authors).

Total Mn concentrations in EAF slags are similar to or higher than other types of ferrous slags. They generally exceed residential soil screening levels for Mn, but do not always exceed industrial screening levels, for the reported data. EAF slags generally have high total Cr that exceeds both soil residential and industrial screening levels. Other elements with total concentrations that exceed soil screening levels in some ferrous slag samples are As, V, and Pb.

The high concentrations of Mn and Cr in steel slags, including EAF slags, compared with other ferrous slags can be attributed to the greater contribution of recycled steel scrap to the feedstocks for steelmaking plants or to the addition as an alloying element with iron during stainless steel production (Piatak et al., 2021). In unweathered slags, these elements are found mostly in spinel group minerals (AB2O4, where A = Fe2+, Mg, Mn, or Zn; and B = Al, Cr, or Fe3+), including chromite (FeCr2O4), pyroxenes (XY(Si,Al)2O6, where X = Ca, Na, Fe2+, or Mg; and Y = Cr, Al, Fe3+, Mg, Mn, Ti, or other trace elements), or substituted as a minor or trace element in silicate glass. Other Mn phases that have been reported in ferrous slags include MnO (manganosite), Mn3O4 (hausmannite), MnO2 (groutellite), and MnS (alabandite) (Piatak et al., 2021). Vanadium is an important additive for the production of ferrovanadium or vanadium-bearing steel alloys, where V concentrations in steel products range from 0 to 4.2 percent (Petranikova et al., 2020). Vanadium occurs in Fe-V spinels and Ca-V oxides, as well as a trace substituent in other oxide and metal phases, as reduced V3+ or V4+ (Yang et al., 2018a; Piatak et al., 2021). Variable concentrations of V are found in EAF and other steel slags (Figure 3-2c). Arsenic would be present in trace concentrations as As3+.

A recent compilation of slag compositions from blast furnaces from Chinese samples (Wang et al., 2021) (not included in the Piatak et al. compilation) reported trace elements that fell within the ranges reported by Piatak et al. (2021). They also reported mercury (Hg) and selenium (Se) concentrations and radionuclide activities from a few studies, elements that were not reported by Piatak et al. (2021). They note higher concentrations of Hg and Se in blast furnace slag samples than for steel slags. Activities of average 232Thorium and 226Radium in blast furnace slags were about 34 and 2 times higher, respectively, than the soil background levels. 232Thorium in steel slags was on average about 6 times higher than soil background and 226Radium was below background (0.8), although measurements were variable (Wang et al., 2021).

ORGANIC POLLUTANTS FROM PLASTIC MATERIALS MIXED WITH SCRAP STEEL

Because there are many plastics in the scrap used in EAF steelmaking, there is an opportunity for the formation of gases that can contain halogens and organic toxins. This in turn leads to several concerns about persistent organic pollutants (POPs), which are organic chemicals with the potential for long-range transport, persistence in the environment, and biomagnification and bioaccumulation in ecosystems that can cause significant negative effects on human health and other organisms. One concern is about the prospects for POP contamination of EAF slags. Another concern, which is outside of the committee’s statement of task, is the possible emissions landscape for POPs from steelmaking plants.

POPs of high concern are the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polychlorinated dibenzo-dioxins and furans (PCDD/Fs), and the polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs). Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and their partial thermal degradation product telomeres are of increasing interest in related pyrolytic processes (Thoma et al., 2022). Each of these families of organic compounds has a range of chemical properties, environmental persistence, and toxicities. Their background concentrations in ambient air range from sub-picograms per cubic meter (pg/m3) up to tens of nanograms per cubic meter (ng/m3) (Ohura et al., 2012). The most abundant class of these pollutants are the nonhalogenated PAHs ranging to tens of ng/m3. The dioxins and furans are least abundant. Some of these compounds occur in nature, and halogens can be present in coal and natural slag smelting fluxes. But many of these compounds in ambient air are thought to be a widely dispersed industrial pollution legacy. That is because the emissions from industrial and transportation sources of these materials can be 1,000 times or more concentrated than the ambient values observed. The relative abundances of POPs would undoubtedly shift toward halogenated PAH if more halogens were to become available to the various formation and reformation processes in the thermal processes to which the industrial mass flows are subjected. This potential shift to more halogenated POPs would be unfortunate as the halogenated compounds are generically more toxic. These families of compounds span the range from volatile to semivolatile, so their emissions could occur both in the gas phase and in any PM (particulate matter), such as fly ash or slag and its related dust.

Steelmaking, by EAF or other means, incorporates streams of carbonaceous materials. Typically, these are coal, coke, natural gas, and derivative carbon monoxide. The streams serve diverse roles as process reductants, process fuel for maintaining temperature, and slag foaming agents. Current sustainability interests within many sectors of the economy, that require high-quality process heat, have turned to combustion of carbonaceous waste streams as a source of process heat for otherwise difficult or expensive to dispose of waste streams. Examples of this are the burning of municipal waste in incinerators to generate electricity, the burning of municipal waste and/or waste tire–derived fuels in cement kilns, and the incineration of liquid hazardous wastes in expanded aggregate kilns.

The attractive features of wastes for fuel have been tarnished by the signal failures in many areas of application to properly control the toxic emissions generated in the process through incomplete combustion. Dioxins and furans are of particular concern with waste streams that contain halogenated material, such as municipal waste or PCB-bearing liquid hazardous wastes. EPA has very stringent procedures for cooling of exhaust flue gases by heat exchange to limit dioxin/furan reformation before emission to the environment because of these concerns in hazardous liquid waste incineration. Sometimes these procedures are not followed (e.g., see LaPosta, 2020). It is unknown whether the steel industry has any plans to try incorporating carbonaceous waste streams into its processes, which could make a substitute fuel source for coal, coke, or natural gas. Of particular concern in EAF slag is the potential for halogenated plastics to be in the waste stream, which may provide the basis for increased dioxin/furan emissions. The use of municipal waste, tires, and raggertail paper/plastic reprocessed waste in the cement industry is an early expression of this interest. It is clear that all organic compounds generated in the steelmaking process are not completely burned off. In fact, uncombusted CO is used to foam slags to improve their insulating capacity; some portions of the CO and other organic compounds remain trapped in the vesicles while other parts are undoubtedly emitted as flue gas. If halogenated plastics are in the mix, either as components of

alternate fuels or a part of the scrap steel stream, trapping and distribution of dioxins and furans in slags and associated dusts becomes a worrisome possibility.

There are considerations inherent in EAF steelmaking and in the chemistry of the more toxic POPs that make these concerns about EAF slag more pressing than they may be for other modes of steelmaking and their slags. These concerns arise from the intrinsic content of halogenated wire insulation and coatings on scrap steel, such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC) on copper (Cu) wire in automotive scrap, brominated flame retardants, and the like. The high Cu content of EAF steels sets them apart from other steels as mentioned in Chapter 2. The failure to recover Cu wire during scrap steel recycling ensures that wire insulations like PVC will also be in the scrap charge to the EAF.

The toxicity (mutagenic and carcinogenic) of PAH increases with the number of rings. Nisbet and LaGoy (1992, Table 4) show the relative toxicities of environmentally tracked PAHs. It is important to note that five-member-ringed dibenzo(a,h)anthracene and benzo(a)pyrene are 10–50 times more toxic than fourmembered benzoanthracene, about 100 times more toxic than three-membered anthracene, and about 1,000 times more toxic than two-membered naphthalene. Another consideration is that the volatility of the PAH drops dramatically with the number of rings. The higher-membered rings are more condensable as tracked, for example, with partition coefficients for the PAHs between liquid octanol and gaseous air (KOA). The higher ring numbers partition much more strongly into the condensed phase octanol than into air. This leads to the expectation that heavy PAHs will be found in greater concentration in aerosols and filterable PM than in a cogenetic (flue) gas phase.

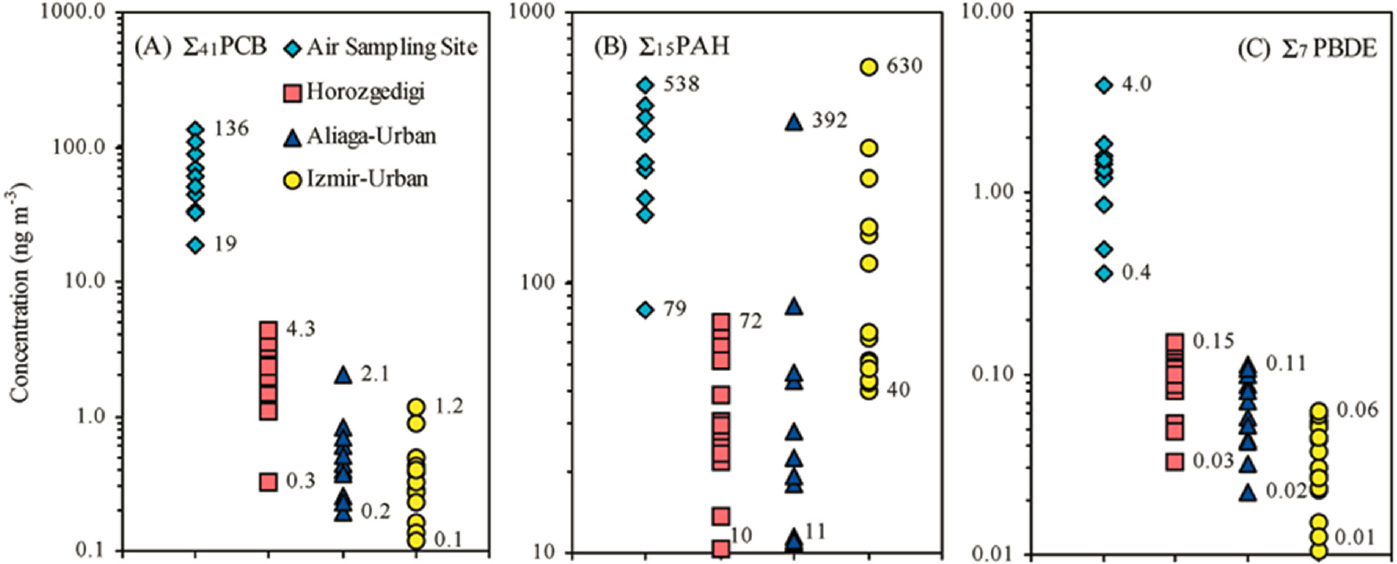

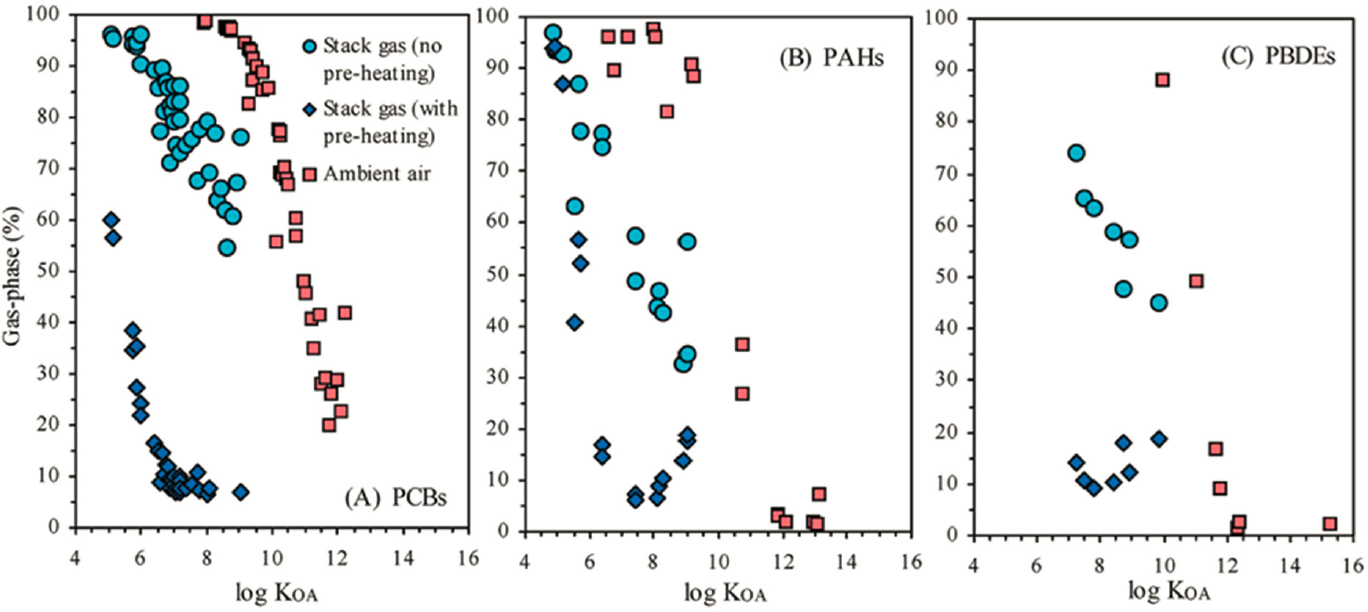

This expectation is confirmed by Odabasi et al. (2009) in their study of gas phase and coeval PM from EAF stack emissions in a steelmaking region of western Turkey. Jackson et al. (2012) provide a comparison study of PAH, PCB, and PCDD/F emissions in BOF steelmaking in the United Kingdom. Khaparde et al. (2016) track PM10 and PAHs around an Indian BOF steel plant. The ambient air in the rural region of Turkey was 10–100 times less polluted with PAHs, PCBs, and PBDEs than EAF stack flue gases; see Figure 3-3. Filtration and separated analysis of particulate- and gas-phase POPs show a striking negative dependence of the percent of total measured individual pollutants in the gas phase and the octanol–air partition coefficient (KOA); see Figure 3-4.

NOTE: See text for discussion.

SOURCE: Odabasi et al. (2009, Fig. 2).

NOTE: See text for discussion.

SOURCE: Odabasi et al. (2009, Fig. 3).

The collective meaning of these observations is that EAF steelmaking is a big contributor to the POPs of its neighboring region, and that the most toxic fraction of the POP budget will be absolutely and preferentially concentrated in the PM, such as baghouse dust, electrostatic precipitator concentrates, and other slag dusts, which may be added to slag piles. In determining the hazard represented by individual EAF slags, it is important to know the fate of the collected fraction of the solids in the pollution control systems and whether they also reside in the slag, which itself is also a net absorbent of POPs (Yang et al., 2018b). The special capacity for PM to capture the more toxic PAHs in EAFs noted by Odabasi et al. (2009) in Turkey has been confirmed by Baraniecka et al. (2010) for EAFs in Poland and by Chen et al. (2021) for EAFs in Taiwan. There is some variation depending on whether the charging scrap is preheated or not. The principal source of the halogens in EAF discharges of POPs seems to be the paints and coatings on the scrap and any unseparated electrical wire insulation, including brominated flame-retardant materials. Oiled or undegreased scrap may also contribute to the halogen budget. Thus the prospect of domestic EAF slag in the United States also being a high risk for (halogenated) POP exists and requires evaluation in the context of each facility and slag type. The POP database for U.S. domestic EAF slag is very limited compared to data obtained from global sampling and represents an important data gap.

The partitioning of particularly hazardous POP into the particulate wastes of the steel furnace would seem of little immediate concern in evaluating the hazards associated with unencapsulated EAF slag. Fly ash is required to always be treated as hazardous waste and disposed of accordingly, whether it is from steel furnaces, cement kilns, light aggregate kilns, or any other industrial furnace. A small amount of fly ash will inevitably remain with the slag, but this is of much less concern than the concern that arises should the toxic fly ash waste stream be recombined with the slag during processing for disposal. Such a practice persists in the lightweight aggregate industry through lax state oversight even after EPA renounced the particular application of the Bevill exclusion loophole in the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act under which the practice was previously allowed.2 This is mentioned as an example of a current practice, for which foreknowledge is a valuable alert mechanism to avoid spread of the practice. That such a practice has been part of the slag industry historically is noted below in the section on leaching and mobility (Bayless and

___________________

2 People of the State of New York et al v. Norlite, LLC, 2022; see https://iapps.courts.state.ny.us/nyscef/DocumentList?docketId=4EM7TiIwfukqyXkyVxRFIQ==&PageNum=1&narrow=.

Schulz, 2003; Roadcap et al., 2005). Such historical mixtures of fly ash and slag are found in large unlined fill deposits along Lake Michigan’s south shore. These are not proper landfills and are a large tonnage dispersal hazard if reexcavated and are a current groundwater hazard for caustic pH levels.

It is not known whether currently generated EAF slags pose such problems. EPA supplied the committee with a memo summarizing analyses of two weathered EAF slag samples from residential properties in Pueblo, Colorado, in September 2020.3 Target analytes included asbestos, PAHs, PCBs, and dioxins. Overall, given that some organics were detected (albeit at relatively low concentrations compared to EPA’s regional screening levels [RSLs] for residential soil), the results indicate research is needed on the possible contribution of EAF slag to environmental POP contamination. For the two samples analyzed, two PAHs—benzo(b)fluoranthene and fluoranthene—were detected in one of the samples at estimated (J-flag) concentrations orders of magnitude lower than residential soil RSLs using a target excess lifetime cancer risk of 1E-06.4 The same PAHs were not detected in the second sample, and no other PAHs were detected in either sample.

Two sources of uncertainty are important to note. First, the method detection limit exceeded the chemical-specific RSL for some PAHs. For example, benzo(a)pyrene and dibenzo(a,h)anthracene were nondetectable at 170 ppb each; this method detection limit is roughly 1.5 times greater than the RSL of 110 ppb for both PAHs. Second, the RSLs for PAHs continue to rely on toxicity assessments from the 1993 Provisional Guidance for PAHs, until the EPA Integrated Risk Information System program resumes the review of updates proposed in 2010. One PCB, Aroclor (Aroclor 1260), was detected in one sample at an estimated (J-flag) concentration an order of magnitude lower than the RSL. The sum of the toxic equivalents (TEQs) of 16 dioxins and furans analyzed was roughly 1.7 times lower than the lowest TEQ RSL (~3 versus ~5 TEQ). The memo was unspecific about what may have caused PAHs to be detected (e.g., whether any carbonaceous waste streams provided any substance to that EAF process).

The use of carbonaceous waste streams to boost the halogen budget in the system in future EAF slags or the addition of fly ash containing the concentrated toxic substances of combustion to slag would raise concerns about PCDD/F contamination of slag. Thus, it is important to avoid the use of carbonaceous waste streams as part of EAF steel production and any practice of blending fly ash with slag aggregate. Data are needed on POP concentrations in EAF slag and related fly ash to increase understanding of the possible presence and magnitude of this hazard in EAF slag.

WEATHERING AND MECHANICAL DEGRADATION OF SLAG

Slag mineralogy is not static even after it has solidified by cooling. Like the character of slag itself, its further mutability after quenching can be highly variable. If the slag is water quenched and returns as a glass-rich composite containing crystals and bubbles, its mechanical and chemical integrity are highly dependent on the details of the slag itself and the quenching rates. Viscous siliceous slags behave quite differently than easily crystallized, highly basic, lime-rich slags. Glassy, bubble-rich slags tend to be physically weaker and more vulnerable to chemical and mechanical degradation than well crystallized slags.

The principal mechanisms of slag evolution are mechanical degradation (also referred to as comminution), hydration (and potential expansion), carbonation, agglomeration, dissolution, and leaching. Some of these mechanisms, particularly dissolution and leaching, may be assisted by microorganisms. These mechanisms can act in sequence or in parallel. For instance, the mechanical comminution by the slag processor may occur even as environmental moisture and atmospheric CO2 begin to act on pristine slag. The comminution process may continue beyond the slag processor’s yard if the slag is used as road metal (as an aggregate for construction or repair). The mechanical degradation of slag into smaller fragments under traffic may compete with agglomeration of particles by formation of calcium silicate hydrate through the hydration of lime-rich slags. Comminution and agglomeration proceed in parallel with partial

___________________

3 N. Birchfield, EPA/OLEM, personal communication, November 8, 2022.

4 See https://www.epa.gov/risk/regional-screening-levels-rsls.

dissolution and leaching into groundwater or surface water. The degradation process of slags is no less variable than the considerable variations in the types of slags themselves. Thus, a universal road map for EAF slag decay is not possible, beyond a few general expectations.

The first general expectation is that slag mineralogical complexity will increase in the weathering process before all material is reduced to the simple geological baseline of complete degradation and erasure by dispersal. The weathering process adds new minerals, colloids, and solutions before all original material is removed.

Another general expectation is that, for modest timescales of months to decades, the bulk of the slag (by mass and volume) will increase with time through greater environmental additions of moisture and carbonate than by the lesser removal of material by leaching. The addition of water and CO2 to the slag that occurs through mineralogical reconstitution during weathering provides an opportunity for liberation of leachable material beyond that which occurs from stable minerals. But the net material transfer favors growth of slag mass and volume. The growth of portlandite, Ca(OH)2, from any free lime happens on the timescale of weeks to months in exposed slag with significant volume/mass increase of the slag. Slag is allowed to mature outdoors several months before it can be used in applications requiring volume stability. Carbonation also leads to slag mass and volume increase, but this is more a geological timescale process than an industrial one. The long-term fate, centuries or more, of the stable silicates and oxides in slag is poorly characterized, except to note that matrix glass decays more rapidly in general than crystalline phases.

ENVIRONMENTAL WEATHERING OF SLAG

Weathering refers to processes of mineral and rock alteration at the Earth’s surface. Chemical weathering reactions often involve water and oxygen at low temperatures and pressures and are mediated by microbial activity, as noted previously. Rates of weathering are a complex function of many variables, including the chemical and physical characteristics of the initial material, local environmental conditions, temperature, and time. As such, they are highly variable spatially and temporally (Kierczak et al., 2021; Reddy et al., 2019). In general, mineral alteration reactions associated with the weathering of steel slags under normal surface conditions are acid-consuming reactions that generate alkaline (high pH) conditions. Ferrous and steel slags are dominated by oxide and silicate minerals, and generally have a low abundance of sulfide phases, in contrast to base metal slags that often contain sulfide minerals with a range of heavy metals. Sulfides tend to weather rapidly in oxidizing environments, but this pathway for the release of toxic metals is not important for ferrous slags that lack sulfide minerals (Kierczak et al., 2021).

Two common reaction classes associated with slag materials are carbonation, involving reaction of primary silicate minerals with carbon dioxide (CO2), and oxidation, in which minerals with reduced elements react with environmental oxidants such as O2 and water. In surface environments in the presence of water, these reactions are typically accompanied by mineral hydration as well. For example, the carbonation of a calcium–magnesium silicate ((Ca, Mg)SiO3) produces magnesite (MgCO3), calcite (CaCO3), and silica (SiO2):

(Ca, Mg)SiO3 + CO2(g) = (Ca, Mg)CO3 + SiO2

The hydration of lime (CaO) in slag to portlandite (Ca(OH)2) accelerates the process of carbonation to form calcite (Kierczak et al., 2021):

CaO + H2O(l) = Ca(OH)2

Ca(OH)2 + CO2(g) = CaCO3 + H2O

The ability of steel slags to consume CO2(g) and sequester it in carbonate minerals has been suggested as a beneficial use of these materials if optimized and used on a large scale (Pan et al., 2016; Reddy et al., 2019). However, the fluids involved with these processes are extremely caustic (pH 12–13) and require some diligence for their safe handling.

The extent of mineral alteration in the environment is strongly dependent on grain size; physical properties, such as cracks or fissures; the amount of contact with water and oxygen; and whether secondary phases provide surface armoring that slows alteration or are soluble and easily removed. Common secondary phases that result from weathering of ferrous slags include a wide range of carbonate, oxyhydroxide, hydroxide, and mixed hydroxo-carbonate phases with minor sulfate and phosphate minerals (Kierczak et al., 2021; Neuhold et al., 2019). Slag products contain both crystalline phases and glass (X-ray amorphous) materials. Similar to natural volcanic glasses, more rapid weathering of glass in slags compared to crystalline phases has been observed in some cases, often by hydration and hydrolysis reactions. For example, alteration of iron-rich glass in ferrous slags produces brownish ferric hydroxide or oxyhydroxides that may sorb or co-precipitate with trace elements (Kierczak et al., 2021; Reddy et al., 2019).

MECHANICAL DEGRADATION OF SLAG

The potential for breakdown of EAF slag coarse aggregates into smaller particle sizes (e.g., smaller than PM10) that create exposure risks is a primary factor in the assessment of the dangers in using unencapsulated slag. In addition to the increased inhalation efficacy, the increased surface area can increase rates of surface chemical reactions. However, much of the material testing on slags has focused on the mechanical strength and abrasion resistance during evaluation of use in varied engineering applications. There is a rich literature on the strength consequences of using slag aggregate in concrete, asphalt, and other encapsulated mixes (e.g., Revilla-Cuesta et al., 2022; Tamayo et al., 2020; Vaiana et al., 2019). However, when aggregate strength is assessed outside of a mix, strength measurements are relatively more limited. In addition, across these measurements, testing approaches vary widely and the focus is on how much of the aggregate remains intact rather than on the fine materials abraded off. These data constraints preclude straightforward generalizations or inference of central tendencies in physical properties from available data and limit assessment of slag breakdown during unencapsulated use.

Yildirim and Prezzi (2009) noted the limited information on engineering properties of both BOF and EAF steel slag more than a decade ago. Table 3-2 summarizes a variety of engineering measures of steel slags and EAF steel slag in particular.

TABLE 3-2 Engineering Measures of Steel Slag, Limestone, and Granite

| Material – Study | Los Angeles Abrasion (ASTM C131) | Micro Deval, by Percent Weight | Expansion Volumetric Stability (ASTM D-8378) | Bulk Specific Gravity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steel Slag – Noureldin and McDaniel (1990) | 20–25 | 3.2–3.6 | ||

| Steel Slag – Aiban (2006) | 18 | 3.69 | ||

| Limestone – Cook and Dessureault (2022) | 19–30 | 8–30 | ||

| Granite – Cook and Dessureault (2022) | 27–49 | 2–23 | ||

| EAF Slag – Gökalp et al. (2016) | 23–30 | 5–12 | 3.3–3.4 | |

| EAF Slag – Tozsin et al. (2023) | 0–1.8 | 2.8–3.3 |

NOTE: The engineering measures are described in the narrative text.

The Los Angeles abrasion test is a drum test, where a specific size class sample of aggregate is placed in a rotating drum with a specific number of stainless steel bearings. After rotating the sample, it is re-sieved, and the mass loss is reported. In general, as shown in Table 3-2, fresh slag abrades at a similar rate to other common rock aggregate types. However, this measure does not capture the implications of interactions between chemical and physical weathering on longer-term abrasion, nor does it capture the size classes of the material abraded.

The Micro Deval test allows some insight into the interaction between water and mechanical wear. The Micro Deval is similar to the Los Angeles abrasion test, introducing the sample to a drum with steel ball bearings and rotating the sample. However, the Micro Deval testing is done with water in the drum. In general, these abrasive losses are similar to those observed for other rock aggregates and smaller than those observed for slags using the Los Angeles abrasion test. However, this testing is still limited to fresh samples of slag. These evaluations do not indicate how slag aggregates that have been emplaced for several years abrade.

The expansion of EAF slag during weathering can influence the breakdown of slag aggregate into smaller pieces. If expansion occurs along a linear or planar orientation of the expansion-prone mineral phases, this expansion can create or enhance fractures in the aggregate and hasten the abrasion of the clasts—a clast being one of many fragments that form a multicomponent rock. A clear understanding of this expansion behavior in unencapsulated slag is complicated by the practice of slag processors to weather the slag materials prior to sale, allowing expansion before processing and resulting in a more stable product. Table 3-2 summarizes some measures of expansion, but these are measurements on products obtained post-processing and do not reflect expansion commonly observed in fresh slag. Yildirim and Prezzi (2009, Table 3.9) note that materials with persistent, elevated expansion rates are generally selected for unencapsulated uses. Thus, unencapsulated slag may be more prone to expansion effects due to the combination of providing materials that expand more and exposure to moisture due to the unencapsulated use.

Steel slag bulk density is generally higher than other lithological materials (see Table 3-2). This is due to the elevated iron content in slag when compared to the alumino-silicate matrix more typical of common lithological materials.

The Leaching Environmental Assessment Framework (LEAF) analyses, though limited in sample size, also indicate slag is similar in strength to, if not stronger than, coarse granite aggregates. The results of the LEAF analyses presented to the committee (Garrabrants et al., 2022a,b)subjected EAF slag aggregate samples to both physical and chemical processes, though in series rather than as parallel processes. Assessment of the effects of physical processes on durability relied on mass loss from specific clast size ranges after five freeze–thaw cycles and, separately, after 500 revolutions in a drum with steel bearings. While these measurements suggest that physical processes tend to abrade granite aggregates more effectively than slag aggregates, this approach does not allow assessment of the size classes of the abraded materials.

Importantly, the LEAF testing did evaluate slag materials that had been emplaced for 15 years. This emplaced slag sample contained about 19 percent of particles smaller than 16 mm, indicating the slag was breaking into smaller particles (most fresh slags contain 5 percent or less of material in that size class). This is apparently the only measurement of emplaced slag abrasion in the literature. While examination of a similar process in common rock aggregates might provide some insight into these long-term abrasion processes, there appears to be limited or no data from equivalent measurements on samples taken from emplacements of other aggregate types.5

The particle size compositions of materials abraded from unencapsulated slag is an important gap in the assessment of its use. While there are data to capture a range of possible variations in chemical composition and the resistance of slag to abrasion, there are limited available data on the sizes of abraded material for assessment of the potential impact of abraded materials. Slag might be more resistant to abrasion than other common rock aggregates, yet aggregates still produce dust. Assessment of risk in unencapsulated slag will remain imprecise without additional measurements of slag aggregates, particularly

___________________

5 See further discussion of LEAF below, “Leaching Test Methods.”

measurement of long-term emplaced abrasion and measurement of the size classes produced, rather than simply the material lost during abrasion.

The assessment of wear byproducts from EAF slag is often more difficult than assessment of rock aggregates given the relatively variable chemistry and heterogeneous mineralogy of EAF slag. These heterogeneities, when combined with any tendencies in the physical weathering of EAF slag aggregates, can result in particles with combinations of size and chemistry distinct from commonly used rock aggregates. Furthermore, these smaller particles have higher surface areas that can influence the chemistry of the resulting leachate. As noted previously, the nature of slag breakdown products following emplacement is even less clear.

The realm of possibilities in the wear of EAF slag is also fundamentally site specific. In particular, the relative roles of chemical and physical weathering depend largely on local climate. Breakdown of slag aggregates in drier climates is likely driven proportionally more by mechanical stresses (e.g., loadings, thermal). In contrast, with increasing moisture, the role of chemical weathering processes and the interactions of chemical weathering processes with physical weathering become increasingly important.

In addition, the use of coarse EAF slag for areas where loadings are frequent (e.g., driveways, railroad bed aggregates) raises the potential for physical deterioration of slags into smaller particles. This type of wear over time has not been considered in the risk assessments that have been done.

The size distributions of fugitive dust from gravel processing facilities can include particulate matter (PM) small enough (PM10, PM2.5, and smaller) to create health exposure risks (Shiraki and Holmen, 2002). Stone crushing activities (analogous to methods used to transform slag to coarse aggregate) create small-sized PM (Sivacoumar et al., 2009). While potential exposures during these processing steps are characterized, it is not clear how much fine PM is emplaced with either gravel or crushed slag. There is some evidence that slag sources may have a smaller proportion of fine PM than traditional coarse aggregate sources (Kacer et al., 2023). In particular, during the LEAF analyses of EAF slags, reject sizes (i.e., smaller than 16 mm) constituted about 5 percent in emplacement ready samples (i.e., fresh aggregate). Ambient PM has been measured during dumping of gravel (Muleski et al., 2005) and the repair of gravel railroad beds (Park et al., 2022). Fine PM is associated with coarse aggregates, but the amount varies, and potential for mobilization depends upon use. Potential exposures could be mitigated by fine cleanliness standards specified to minimize smaller particle content at emplacement. However, these specifications are only as effective as the enforcement of the specifications.

Beyond the relative proportion of fine PM at emplacement, the ongoing contributions of fine particles created by physical wear of the EAF slag aggregates are not clear. LEAF testing results suggest that EAF slag aggregates are relatively resistant to physical weathering; however, laboratory simulations of physical weathering processes cannot capture all processes encountered during actual emplacements. As noted previously, the standardized abrasion testing provides limited insight into the breakdown of slag after emplacement. EAF slag may abrade relatively less than other aggregates due to physical properties, but interactions between chemical and physical processes, particularly expansion of the slag during aging is incomplete, could alter these abrasion rates.

Without additional observations of EAF slag breakdown over years of emplacement and across application types (road beds, driveways, etc.), the implications of wear, particularly for the generation of fine particles, are poorly constrained. Given the increased surface area and additional inhalation risks in these finer size classes, evaluation of these long-term wear patterns is essential for characterization of unencapsulated use of EAF slag.

RELEASE AND ENVIRONMENTAL TRANSPORT OF TRACE SLAG CONSTITUENTS

The environmental release of minor elements from slag that may be of concern is controlled by the weathering of their primary silicate and oxide host phases. Trace elements present in reduced oxidation states in slag minerals will oxidize with weathering, at least at particle surfaces, but many factors will influence whether these elements are leached and mobilized in water. A few studies have directly examined weathering processes in steel and other ferrous slags specifically, but mineral weathering processes and

alteration products are similar to those observed in soils and weathered igneous rocks. Table 3-3 highlights several trace elements in EAF slag of potential environmental concern based on their chemical speciation.

| Element | Slag | Weathered a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidation State | Host Phases | Oxidation State | Occurrence | |

| Manganese (Mn) | Mn2+, Mn3+ | spinel phases (AB2O4: A = Fe2+, Mg, Mn, Zn; B = Al, Cr, or Fe3+), pyroxenes (XY(Si,Al)2O6: X = Ca, Na, Fe2+, or Mg; Y = Cr, Al, Fe3+, Mg, Mn, Ti, or other trace elements), manganosite (MnO), hausmannite (Mn3O4) |

Mn4+, Mn3+ | MnO2 sheet (birnessite, vernadite) or tunnel (todorokite, hollandite) structures; Mn3+ oxyhydroxides; mixed Mn, Fe hydrous oxides |

| Chromium (Cr) | Cr3+ | chromite ((Fe,Mg)Cr2O4), other spinels | Cr3+ Cr6+ | Fe1–xCrx (OH)3(s), Cr(OH)3 (aq, sorbed) HCrO4–, CrO42– (aq, sorbed) |

| Vanadium (V) | V3+, V4+ | Impurity in titaniferous magnetite (Fe2+(Fe3+2(1-x),(Fe2+Ti)x)O4), other spinels, Ca-ferrite minerals | V5+, V4+ | Fe3+VO4·5H2O(s), H2VO4– , HVO42– (aq, sorbed) VO2+ (aq, sorbed) |

| Arsenic (As), Antimony (Sb) | (As, Sb)3+ | Impurity in spinels and oxides; substitutes for Fe3+ |

(As, Sb)5+ | H2(As, Sb)O4– , H(As, Sb)O42– (aq, sorbed) co-precipitated with Fe3+ hydrous oxides |

a Surface weathered under aerobic conditions.

Manganese

In unweathered slag minerals, manganese is present mostly as Mn2+ in spinel phases, as MnO, or in solid solution with Fe and Mg ((Fe1–x–y-z, Mgx, Mny, Caz)O2), with lesser Mn3+ present in some slags. In oxidized surface environments, Mn will oxidize to Mn4+ oxides and mixed Mn, Fe hydrous oxide phases. In surface soils and sediments, Mn4+-oxide minerals (manganates) are widespread and form readily as a result of coupled chemical and biologically catalyzed pathways (Spiro et al., 2010). Manganates are structurally diverse, forming a variety of sheet and tunnel structures with mostly Mn4+ and lower fractions of Mn3+, and typically contain a range of impurities often dominated by Fe (Post, 1999; Zahoransky et al., 2022). Mn3+ oxyhydroxides (MnOOH polymorphs) and mixed Mn, Fe hydroxide phases are also common weathering products. Manganese oxides generally have low solubilities, but reductive dissolution to Mn2+ can occur under mildly reducing conditions over a range of pH and autocatalyzed by aqueous Mn2+ (Hinkle et al., 2016; Lefkowitz et al., 2013). At alkaline pH with dissolved carbonate, Mn2+ can precipitate as MnCO3 (or Mn substituted in CaCO3 or FeCO3) if mineral solubility is exceeded and given sufficient reaction time (Leven et al., 2018), or sorb to solid phases. At acidic pH, Mn2+ would tend to be released to solution.

Chromium

Weathering of spinel minerals in slag can potentially release Cr3+, although the solubility of most Cr phases is low, particularly at alkaline pH. There are few natural oxidants capable of transforming Cr3+ to the more mobile and toxic form, hexavalent chromium (Cr6+), under typical surface conditions. In soils

and sediments, Mn4+ oxide minerals have been recognized as an important oxidant of Cr3+ to Cr6+ as the chromate oxyanion (HCr6+O4–, Cr6+O42–) (Oze et al., 2007; Pan et al., 2017a). A weathering sequence of primary Cr-bearing slag minerals might start with the hydrolysis of chromite to Cr3+ hydroxide and oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+ to iron hydroxide (or a mixed Cr3+-Fe3+ hydroxide [Fe1-xCrx (OH)3]):

Fe2+Cr3+2O4 + 5H2O = 2Cr3+(OH)3 + Fe3+(OH)3 + H+,

followed by Cr3+ oxidation catalyzed by manganese oxide. Examples of overall reactions using stoichiometric mineral end members, with variable products as a function of pH, can be written as follows (Pan et al., 2017a):

Cr3+(OH)3(s) + 3Mn4+O2 + H2O = HCr6+O4– + 3Mn3+OOH + H+,

2Cr3+(OH)3(s) + 3Mn4+O2 + 4H+ = 2HCr6+O4– + 3Mn2+ + 4H2O.

Experimental studies have shown that the rate of Cr oxidation depends on the solubility of Cr3+ in the solid phase, which is generally higher at lower pH, and the proximity of Mn oxides to Cr3+ in solids or solution (Pan et al., 2017a). Chromate release to solution depends on a variety of factors, including sorption of chromate, which is higher at alkaline pH; the concentration of competing oxyanions such as phosphate; and the rate and extent of reduction of chromate back to Cr3+, which can occur by biotic and abiotic pathways (Pan et al., 2017a; Reijonen and Hartikainen, 2018). As most studies have examined Cr-Mn reactions under abiotic conditions, the role of microbes and fungi in coupled oxidation–reduction pathways between Cr and Mn is not well known (Liu et al., 2021a).

Few studies have addressed the extent of Cr3+ oxidation to chromate in slag directly, but the available data suggest that the overall amount of oxidation under ambient weathering conditions is relatively low. In one study of slags from stainless steel production, gradual oxidation of Cr3+ was noted over 6–9 months of exposure to air, but only about 0.1–1.0 percent of total Cr was estimated to have converted to chromate (Pillay et al., 2003). A small fraction of Cr oxidation (~1.8%) was noted in a study of Cr-bearing cement and cement composites, which have chemical similarities to ferrous slags (Estokova et al., 2018). Studies also noted a surface passivation effect (improving the corrosion resistance) from the formation of (Fe, Cr)3+ hydroxides or Ca hydroxide, which tends to slow oxidative weathering reactions over time (Pan et al., 2017a; Pillay et al., 2003).

Vanadium

The geochemistry of V is complex, with V occurring commonly in three oxidation states in crustal and surface environments (Gustafsson, 2019). In reduced conditions, V3+ may substitute for octahedrally coordinated Fe3+ or Al3+. In minerals in ferrous slag, V has been associated with titaniferous magnetite, calcium ferrite, and other Fe-bearing oxide minerals (Chaurand et al., 2006; Mombelli et al., 2014). During weathering, V3+ may oxidize to V5+ as the vanadate oxyanion (H2VO4–, HVO42–), which is the more toxic V species, or to V4+ as the vanadyl cation (VO2+), which is stable in acidic and moderately reducing conditions (Chaurand et al., 2006; Gustafsson, 2019). Vanadate has a high sorption affinity for Fe3+ and Al3+ hydroxides and oxyhydroxides from mildly acidic to alkaline conditions, which is a primary attenuation mechanism in oxidizing environments. It also has structural similarity to the orthophosphate anion (–PO43–) and can substitute in apatite-type minerals. Both the vanadate anion and the vanadyl cation form complexes with organic ligands, and similar to other redox-active elements, environmental oxidation state changes of V are mediated by bacteria and fungi (Gustafsson, 2019).

Arsenic and Antimony

The environmental behavior of arsenic (As) has been studied extensively, and antimony (Sb) shares similar geochemical properties. In oxygenated surface water of pH ~4–10, As typically occurs as an

oxyanion, either as arsenite (H3As3+O3, also written as As3+(OH)3), under moderately reduced conditions, or as arsenate (H2As5+O4–, HAs5+O42–) in oxidized environments. In reducing environments in the presence of dissolved sulfide, As precipitates as relatively insoluble sulfide phases. In slag minerals, trace concentrations of As3+ or Sb3+substitute for Fe3+ in spinels and iron oxides, which will oxidize over time to (+5) oxyanions during surface weathering. Because As and Sb are present at very low concentrations, their mobility is controlled by adsorption and desorption on surfaces and by substitution in secondary phases. Both arsenite and arsenate have a strong, pH-dependent sorption affinity for Fe3+ hydroxide and oxyhydroxide minerals such as ferrihydrite and goethite, which form readily and serve to attenuate the aqueous transport of As and Sb.

LEACHING AND MOBILIZATION OF TRACE ELEMENTS BY WATER

Many hydrologic and geochemical factors influence whether COPCs are mobilized in water from their source minerals in slag. Weathering processes may alter minerals and potentially change the chemical speciation of trace elements, but mobilization by water from a source requires transport, either by dissolution or suspension of particles. Slag materials at the surface would be subject to intermittent leaching by rainfall or water application (e.g., agricultural use). In some instances, slag material might be buried and become porewater saturated. Material at the surface in contact with air would be expected to remain relatively oxidized, while submerged material isolated from the atmosphere could potentially experience a range of reducing conditions. Trace elements weathered from primary silicate and oxide phases may be adsorbed to particle surfaces or incorporated into secondary phases, as discussed previously. Depending on pH and water composition, many of these secondary hydroxide, oxyhydroxide, and carbonate phases are more soluble and can dissolve more rapidly than the original silicate and oxide host phases. Dissolved trace elements are transported in surface or groundwater if not attenuated by adsorption or co-precipitation, and they can also be mobilized by particle or colloidal suspension.

The committee was aware of only a few field studies that have examined the aqueous mobilization and environmental fate of trace elements from steel or other ferrous slag materials. In the United States, one area of study has been the southern margin of Lake Michigan in northeastern Illinois and northwestern Indiana where historical iron and steel manufacturing began in the 1830s (Bayless et al., 1998; Bayless and Schulz, 2003; Roadcap and Kelly, 1994; Roadcap et al., 2005). Slag produced by this industry was widely used in the area to protect from lakeshore erosion; as a railroad and road grade material; as a structural foundation; and to fill low-lying areas, where it was often mixed with other solid waste, such as fly ash, construction debris, dredged sediments, and industrial wastes (Bayless and Schulz, 2003; Roadcap et al., 2005).

Studies of surface and groundwater near these historical slag landfill and pond sites have examined water chemistry relative to background sites not affected by slag deposits. A notable environmental impact is the generation of hyperalkaline fluids (pH 11–12.5) from slag waste sites (Bayless et al., 1998; Bayless and Schulz, 2003; Roadcap and Kelly, 1994; Roadcap et al., 2005). However, concentrations of hazardous trace elements and migration of water with high pH, alkalinity, and total dissolved and suspended solids were variable depending on the site. For example, groundwater with pH near 12 was measured in monitoring wells within a slag landfill (Bairstow Landfill, Hammond, IN), but concentrations of Mn, Cr, and As were below detection. In water sampled from the aquifer beneath the landfill (~0.5–6 m below the slag), pH dropped to 7.4–9.9 and dissolved Mn, Cr, and As concentrations increased (Bayless et al., 1998). In a different slag-affected area, hyperalkaline groundwater (pH ~12) discharged to a spring and mixed with surface water, where pH was neutralized to 7.7 about 6 m downstream (Roadcap et al., 2005). Concentrations of trace elements and COPCs were not reported in the stream, but concentrations in groundwater in the area were generally near or below detection limits.

Studies of these U.S. field sites and others in the United Kingdom (Mayes et al., 2008) have noted precipitation of calcium hydroxide, calcite and other carbonate minerals, and in some cases gypsum (calcium sulfate) that sequesters metal cations, including Fe, Mn, Pb, and other divalent metals. Formation of these secondary minerals within the vicinity of slag deposits limits the mobility of minor and trace

elements in surface and groundwater. The precipitation of secondary sulfide minerals (mackinawite [FeS] and hauerite [MnS2]) was observed in locations where groundwater was anoxic (Roadcap et al., 2005). At the high pH of these systems, release of Mn to water was limited by the formation of secondary oxide minerals such as hausmannite (Mn3O4) and secondary sulfides, and by co-precipitation in carbonate minerals. Mineral precipitation, together with sorption to Fe and Al hydroxides, at high pH effectively limited the migration of hazardous cations and anions from slag sources into water at high dissolved concentrations. However, comparison of metal concentrations in filtered and unfiltered samples suggested that at some sites metals may be transported by colloidal or suspended particles in surface water (Roadcap et al., 2005).

Migration of highly alkaline water from sites of slag weathering can have adverse impacts on surface and groundwater if not neutralized. EPA recommends a secondary standard (a non-enforceable guideline) for drinking water pH of 6.5 to 8.5,6 and a water quality criteria for freshwater for protection of fish and biota of pH 6.5 to 9.7 In terms of ecological effects, discharge of hyperalkaline water from weathered slag into streams and lakes can result in rapid carbonate-dominated precipitation and colloid formation that can smother macroinvertebrate communities and reduce light penetration (Gomes et al., 2016). High pH, high chemical oxygen demand, and oxygen depletion can adversely impact fish and aquatic biota. Aquatic organisms can be affected by ammonia toxicity in highly alkaline water.8 As noted above, however, secondary mineral precipitates from alkaline water can sequester hazardous trace metals (e.g., Pb, Cd, Cu, Co, Zn) and limit their mobility such that transport is much less than in highly acidic water. The elements most at risk for aqueous mobilization are those that form oxyanions (Cr, V, As, Sb, and Mo), although the speciation and attenuation behavior will be different and variable for each element at a specific site and over the wide range of alkaline pH observed around slag deposits (~7.5 to 12).

Leaching Test Methods

The majority of studies have assessed the mobility of trace elements from slag through laboratory leaching tests, particularly as interest has grown in the reuse of slag materials. A number of standardized leaching tests have been established by U.S. and European agencies to evaluate the potential for hazardous elements to be solubilized from solid materials, such as slag given certain environmental conditions. These tests are intended as proxies or worst-case scenarios to assess the risk for mobilization of hazardous elements or chemical species in water. The simplest types are batch tests in which solids, usually of a specified grain size or surface area cut-off, are mixed with an extractant solution at a given pH, or with deionized water at the “natural” pH of the solid (i.e., no addition of acid or base), at a specified liquid/solid (L/S) ratio and reacted for a fixed time. For example, the toxicity characteristic leaching procedure (TCLP) was developed to evaluate whether solid waste should be classified as hazardous for disposal in a municipal landfill based on leached concentrations of specific inorganic or organic contaminants assuming that the solids experienced acidic conditions (pH 4.93 or 2.88) from organic acids (represented by an acetic acid solution) (Kosson et al., 2002). More complicated testing protocols evaluate the extent of element leaching over a range of pH values, or a range of L/S ratios, in either static batch mode or under flow-through conditions to simulate percolation.

Table 3-4 summarizes EPA and European Committee for Standardization (CEN) batch testing protocols that have been most widely used to study leaching from ferrous slag material (Ettler and Vítková, 2021; Piatak et al., 2015; Singh et al., 2021). The TCLP and synthetic precipitation leaching procedure (SPLP) both use an acidic extractant solution while the CEN 12457-2 test employs deionized water as the leachate, which is similar to the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) D3987 test. While single-pH batch tests such as the TCLP or SPLP (and their CEN counterparts) are relatively simple and widely used, these methods have been criticized as not sufficiently representative of the range of

___________________

6 See https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/drinking-water-regulations-and-contaminants.

7 See https://www.epa.gov/caddis-vol2/ph.

8 Ibid.

geochemical conditions that may be encountered in the environment. Newer tests, such as the LEAF, which is composed of four different leaching protocols (EPA Method 1313, 1314, 1315, and 1316), or similar CEN leaching behavior test methods, were developed to address the shortcomings of single pH methods. These tests call for measurement of leached elements or species over a range of pH values in multiple batch tests with either fixed initial pH (EPA Method 1313, CEN 14429) or with continuous pH control during the reaction time (CEN 14997). Other leaching tests in these series examine extraction in batch tests at different L/S ratios (EPA Method 1316) or in column upflow tests (EPA Method 1314, CEN 14405) in which different intervals of column effluent are measured that represent a cumulative L/S ratio of fluid contact with solid over time. While these leaching tests are more comprehensive, they are also considerably more time-intensive and expensive to employ than single-pH batch tests, and thus have been less widely used to evaluate slag materials. Also, some study authors modify standard test protocols if results are not intended for regulatory purposes, which complicates comparison among different studies.

| Method | Leaching Summarya | Reaction Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toxicity Characteristic Leaching Procedure (TCLP): EPA Method 1311 |

|

18 hours | (EPA, 1992) |

| Synthetic Precipitation Leaching Procedure (SPLP): EPA Method 1312 |

|

18 hours | (EPA, 1994) |

| Characterization of Waste—Leaching compliance test for leaching of granular waste materials: EN 12457-2 |

|

24 hours | (CEN, 2015) |

| Leaching Environmental Assessment Framework (LEAF): EPA Method 1313 |

|

24, 48, or 72 hourse | (EPA, 2019a) |

| Characterization of Waste—Leaching Behavior Test. Influence of pH on leaching with initial acid/base addition: EN 14429 |

|

48 hours | (CEN, 2015) |

| Characterization of Waste—Leaching Behavior Test. Influence of pH on leaching with continuous pH control: EN 14997 |

|

48 hours | (CEN, 2015) |

a L/S: Liquid/sold ratio. Natural pH: Measured pH of a solid sample mixed with deionized water with no addition of acid or base.

b pH 4.93 for samples with natural pH > 5; pH 2.88 for samples with pH < 5.

c pH 4.2 for samples from sites east of the Mississippi River; pH 5 for samples from sites west of the Mississippi River.

d 85 weight percent < particle size.

e Reaction time for each particle size cutoff.

Overall, studies of EAF, steel, or ferrous slag materials produced in the United States or European countries generally found very low levels of leaching of hazardous elements using standardized tests, usually reporting concentrations that are not detectable or below regulatory limits. For example, Proctor et al. (2000) analyzed total and leached metal concentrations in 73 composite slag samples, which included 45 EAF slag composites, from 58 steel mills in the United States and Canada produced from 1995 to 1996. All 45 samples were tested by the TCLP method and six representative EAF slag samples were also tested by ASTM D3987 (deionized water leachate at natural pH). Although some total trace element concentrations in EAF slags were greater than soil background levels, none of the leached concentrations exceeded TCLP regulatory standards, and leaching with water indicated strong partitioning to solids (Proctor et al., 2000). Other studies reporting results of leaching tests of iron, steel, or EAF slags have been compiled in Piatak et al. (2015) and Singh et al. (2021). In general, leachates from ferrous slags are higher in pH, alkalinity, Ca, and Si, and lower in cationic metals (e.g., Pb, Cd, Cu, Zn, Co), than nonferrous slags, reflecting the higher solubility of metal cations at lower pH. Although leaching studies of ferrous slags reported detectable levels of trace elements in some cases in both single- and multi-pH tests, leached concentrations were below U.S. regulatory limits; in only a few examples were concentrations above the most stringent standards of European nations (e.g., Mombelli et al., 2016).

Leaching studies of ferrous slags, including EAF slag, have focused on Cr and V in particular as COPCs because of their relatively high concentration in slag minerals and variable solubility as a function of pH and oxidation state. In addition, Ba2+ has also been noted in some studies as more leachable than other cations (Grubb and Berggren, 2018; Mombelli et al., 2016). Most studies report measurement of total Cr without distinguishing between Cr3+ and Cr6+, even though the latter is the more hazardous form. In studies that did measure Cr6+, leached concentrations were mostly not detectable or near detection limits compared with total leached Cr (Grubb and Berggren, 2018; Proctor et al., 2000). Spectroscopic characterization of a BOF steel slag from Austria compared fresh, field-aged (2 years), and leached (47 days) samples and showed that Cr in the slag was present as Cr3+ in all cases (Chaurand et al., 2007). Although limited in scope, these data indicate that oxidation of Cr3+ in slag minerals to Cr6+ is not a prevalent mechanism for Cr release to solution. A similar conclusion was reached in an experimental laboratory study of BOF steel slag that examined its use as a soil liming treatment and determined that the risk of Cr mobilization was low, even in experiments in which MnO2 was added to the soil (Reijonen and Hartikainen, 2018). In contrast, oxidation of V from V3+ or V4+ in slag minerals to V5+ (vanadate oxyanion) appears to be a more prevalent weathering and release mechanism, particularly at alkaline pH, although V mobility is attenuated by its strong tendency for adsorption (Chaurand et al., 2007; Neuhold et al., 2019). As such, the potential for retention of V by organic matter in soils and increased bioaccessibility have been raised as a concern for the use of ferrous slag materials in agricultural applications (Wang et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2018a). A few studies that examined Cr, V, and Ba in host mineral phases and their leaching behavior suggested that mobilization of these elements could potentially be reduced by shifting the composition of the major phases in slag to a higher fraction of iron-bearing Ca-silicates and spinel phases and lower fractions of Al-rich phases (Mombelli et al., 2016, 2014; Neuhold et al., 2019).

Although standardized leaching tests provide insight into the potential for mobilization of trace elements in water, they are generally conducted under oxidizing conditions and fail to capture changes in chemical speciation under reducing conditions and in the presence of dynamic microbiological communities that influence the local geochemistry. Studies to date have not examined the long-term fate of ferrous slag materials in environments with variable or intermittent contact with water of different compositions.

Mobilization of Trace Elements by Air

The potential for small-dimension, high-surface-area PM can arise at multiple points in the EAF slag aggregate life cycle. As EAF aggregates are generally produced by the crushing of slag materials, if processing is not effective, PM produced by crushing could be present during the initial unencapsulated

emplacement. Following emplacement, unencapsulated aggregates are subject to both physical and chemical weathering processes that break the aggregates into successively smaller PM.

Abrasion analyses tend to focus on the loss of fine-size PM from larger clasts rather than the characteristics of the finer particles generated. Therefore, the fine-size classes created during abrasions are necessarily estimated using general approaches. For example, Streiffer and Thiboldeaux (2015) used standard methods for estimating emissions of fine PM from road applications (e.g., using method EPA AP-42). These methods rely on national-scale measurements of silt content in unpaved roads and a series of factors to estimate the fine-sized PM content in road emissions.9 The imprecise measurements of size characteristics of abraded slag therefore limit the effectiveness of this approach.

More generally, the chemical characteristics of PM associated with road construction represent a known gap in national PM emissions inventories (Reff et al., 2009). Furthermore, emissions associated with unpaved roads are estimated to be a substantial secondary contribution to the emission of Fe and other crustal elements in PM (Reff et al., 2009). Given these limitations on risk assessment of aggregate dust in general, potential estimates of slag-derived PM are even cruder.

There are recent comparisons of EAF slag coarse aggregate use with crushed limestone use on gravel roads in Iowa (Kacer et al., 2023). The proportions of PM10 (particles with diameters 10 μm or less and inhalable) in dust mobilized from EAF slag aggregate roads and crushed limestone aggregate roads are not statistically different. Manganese concentrations in the coarse inhalable PM size classes were elevated in the EAF slag dust relative to the crushed limestone coarse inhalable particles (~1.3 times higher), though this difference was not significant.

Given the wide variability in slag composition and the poor characterization of fine PM generation in slag emplacements over the long term, the potential for generation of metal-enriched fine PM cannot be reliably assessed. These particles can be entrained into the atmosphere during normal use (e.g., road traffic, use of parking lots). This gap in understanding is a fundamental need for effective assessment of risks associated with uses of unencapsulated EAF slag.

SUMMARY

As discussed in Chapter 2, slag composition depends on the alloy melted, the source of scrap, and EAF operational practices. Mineralogical variations within different parts of the same batch of slag are driven by the processing and cooling history. It is important to understand slag mineralogy because the minerals themselves are the individual constitutive elements of the potential hazard and resource matrix of slags for unencapsulated uses.

The primary mineralogy of EAF slag reflects the thermochemistry and cooling rate of the parental liquid oxide mix. The extent to which crystallization proceeds, or to which the solidification product is glass, depends on both the slag composition and the cooling rate. Therefore, deviations from equilibrium crystallization are expected when glass forms instead. Glass content of slag tends to increase the leachability of some constituents. Quasi-equilibrium crystallization becomes more relevant than glass formation as the cooling rate slows. Reaction relations between crystals and liquid and length scales of heterogeneity determine departures from chemical equilibrium during cooling.

Weathering adds water, carbon dioxide, and oxygen to slag; degrades mechanical properties; complicates the mineralogy; and can change the chemical speciation and host phases of major and trace elements.

EAF slag is a sharp and hard material which could cause abrasions. Contact with caustic lime-rich slag could cause skin irritations. Inhalation of small particles could cause respiratory distress.

Based on published compilations, slags formed from EAF steelmaking and other ferrous slags generally have lower concentrations of hazardous trace elements than nonferrous slags, although concentrations vary widely.

___________________

9 See https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2023-03/NEI2020_TSD_Section24_Dust_UnpavedRoads.pdf.

The detection of several POPs in EAF slag (albeit at relatively low concentrations compared to EPA’s soil screening levels used for site remediation planning) indicates a need for further study. In addition, because the potential for slag contamination by POPs depends upon the composition of the steel scrap fed into an EAF, it underscores the need for EAF plants to meet the existing regulatory requirements under the U.S. Clean Air Act to prepare and implement a pollution prevention plan for metallic scrap selection and inspection to minimize the amount of halogenated plastics, lead, and free organic liquids that is charged to the furnace.

Concentrations of hazardous trace elements in ferrous slags, particularly Mn, Cr, and V, and, in some reported analyses, As, are elevated above soil screening levels. However, many environmental factors influence whether COPCs are mobilized from slag sources. During weathering, oxidation of Cr3+ and V3+/V4+ substituted in slag minerals can convert these elements to their more toxic forms (Cr6+ and V5+ oxyanions). In general, the extent of oxidation under normal weathering appears low but is not well known. Oxidation of Mn2+/Mn3+ in slag minerals results in formation of Mn4+ oxide minerals, which have low solubility at alkaline pH. The most commonly reported environmental impact from weathering and leaching of ferrous slags is highly alkaline pH in leached water impacting surface and groundwater. A few studies have shown that alkaline water occurs in and near historical slag deposits, and is neutralized rapidly after migration off-site. However, generation, migration, and neutralization of alkaline water from slag weathering has not been extensively studied in the field.

The leaching behavior of hazardous elements from slag has been examined mostly in standardized laboratory leaching tests and varies strongly as a function of pH. Metal cations (e.g., Mn2+, Ba2+, Pb2+, Cr3+) tend to mobilize at acid pH, while oxyanions (e.g., of Cr, V, As) have variable leachability over a range of pH. Studies of EAF and other ferrous slags generally find minimal leaching of hazardous elements in standardized tests, usually reporting concentrations that are not detectable or below regulatory limits. Possible retention and increased bioaccessibility of V in soils has been raised as a concern regarding slag use in agricultural applications. In general, studies to date have not examined the long-term fate of ferrous slag materials and trace element release in variable environmental conditions.

Generation of alkaline pH in leached water during slag weathering can adversely affect surface and groundwater, and influence trace element solubility and mobilization. More information is needed about pH effects and the long-term fate of potentially hazardous trace elements in ferrous slags in variable surface and subsurface environmental conditions. Also needed is better characterization of the particle size range of weathered slag.