Health Risk Considerations for the Use of Unencapsulated Steel Slag (2023)

Chapter: Summary

Summary

Steelmaking is the process of producing steel from iron ore or steel scrap. In 2022, approximately 75 percent of the steel produced in the United States was from the electric arc furnace (EAF) process, in which an electric current is used to produce an arc that melts scrap steel or other iron-containing materials. Slag is the liquid oxide that results from the production of steel. After it is removed from the liquid metal layer, the slag layer is allowed to cool to a solid rock-like matrix and transported to slag processors for use as aggregate. Slag is used in two forms: encapsulated, contained in asphalt or a similar cover that prevents access to it, and unencapsulated, used in a loose or unbound aggregate form. Unencapsulated slag is used principally for ground cover material, which can include residential landscaping and driveways, construction project entrances, road bases, parking lots, embankment fill, and soil remediation.

The amount of EAF slag produced is estimated to be between 10 percent and 15 percent of the weight of steel produced. Thus, the estimated weight of EAF slag produced in the United States in 2022 ranged between 5.9 and 8.9 million tons. Management of the use and disposal of slag is up to the states and varies widely from state to state. Some have chosen to regulate it as a solid waste, while other states have chosen not to do so. More than half of the operating steel facilities in the United States are in states that exempt slag from the definition of waste and consider it a consumer product. Some states allow residential use; other states do not.

Because EAF slag is caustic in nature and contains toxic constituents, such as manganese and chromium, to which humans could be exposed, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to form a committee to review existing information and assess human health risks associated with unencapsulated EAF slag. The committee was asked to consider the potential release of toxic constituents from unencapsulated EAF slag over time, aspects of human exposure to those constituents, advances in the understanding of the toxicology of important constituents, subgroup characteristics associated with the highest sensitivities to exposures, and other important factors that may lead to elevated health risks. The committee was also asked to identify research needed to fill important information gaps. The committee focused on exposures and health risks associated with the use of slag for residential applications.

CHEMICAL PROPERTIES OF SLAG

The chemical composition of slag reflects the steel alloy being produced as well as other components added to develop an appropriate slag chemistry and volume for efficient furnace operation. The chemical composition of EAF slag varies according to the grade of steel produced, source of the scrap used as a feedstock, and EAF operational practices. EAF slag is rich in ferrous oxide (1–50.9%), manganese oxide (0.4–15.6%), lime (2.3–60%), silica (5–32%), and alumina (2–22.6%).1 Stainless steel EAF slags contain significant quantities of chromium oxide (3–7%) due to the high chromium content of stainless steels. Among the many other elements that can be present in EAF slags at concentrations of less than 1 percent (in weight) are nickel, cadmium, lead, zinc, vanadium, titanium, molybdenum, tin, arsenic, antimony, and barium. The slag concentrations of some hazardous trace elements, such as manganese, chromium, and vanadium, can be higher than soil screening levels set by regulatory agencies for site remediation.

Standardized laboratory testing generally has found that minimal leaching of hazardous elements from EAF slag usually occurs in concentrations that are not detectable or are below regulatory limits. In

___________________

1 Ranges in the compositional data suggest there was co-mingling of the EAF slag samples with ladle slag samples, as low values of FeO and MnO are not normal in an EAF slag but are representative of the ladle slag chemistry. Ladle slag is formed during the secondary stage of steelmaking (see Chapter 2).

general, studies to date have not examined the long-term fate of slag materials and trace element release under variable environmental conditions.

HUMAN EXPOSURE TO SLAG CONSTITUENTS

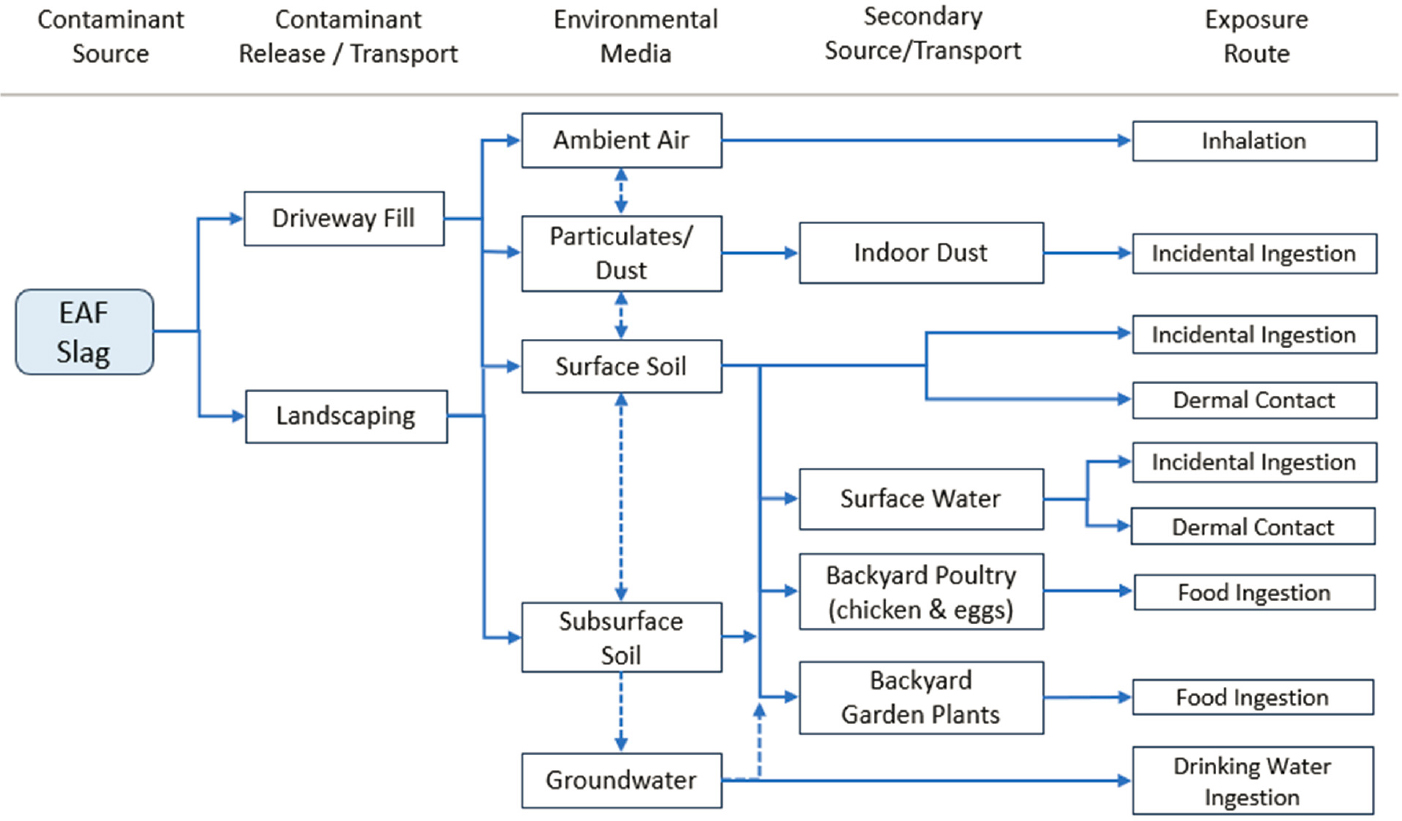

A conceptual site model can be used to illustrate pathways and routes by which humans can be exposed to slag chemicals of potential concern. Figure S-1 shows a generic model that may apply to sites where EAF slag is used in an unencapsulated manner in a residential setting, such as for driveway cover or yard landscaping. The actual model at each site will depend on numerous factors, including the amount and type of slag used, human activity patterns, and local soil and climate conditions. The following factors are likely to be relevant to most residential use scenarios for EAF slag:

- Small-sized particulate matter may be generated and contribute to the indoor dust reservoir, where incidental ingestion occurs, particularly among toddlers.

- Outdoor contact with slag or slag mixed with soil may result in incidental ingestion and dermal contact.

- Inhalation exposure may occur, depending on the particle size distribution of slag and extent of areas where slag is applied.

- Slag used in landscaping could contribute to human exposure from home-produced foods, such as poultry (i.e., chicken meat and eggs) and garden fruits and vegetables that transfer slag contaminants to humans.

- Transport of contaminants through the soil may contribute to contamination of groundwater or surface water, resulting in potential exposures via ingestion and/or dermal contact.

RISK FACTORS AND DATA NEEDS

In previous assessments considered by the committee, screening-level analyses of specific residential use scenarios of unencapsulated EAF slag indicated an exceedance of established risk thresholds, and analyses of other scenarios reported risks below those thresholds. However, due to uncertainties in the current evidence stream, the committee was unable to make an overall characterization of risk related to unencapsulated EAF slag use in the United States.

Therefore, until more studies have characterized a wider range of weathered EAF slag materials and environmental conditions, the committee cautions against making generalizations from conclusions from published risk assessments.

Due to data limitations in the scientific literature, the committee was unable to examine quantitative relationships between human health outcomes directly from the levels of chromium and manganese exposures expected from unencapsulated slag used for residential applications. Therefore, the committee relied on studies of health effects from exposures to chromium and manganese in general.

Based upon its review of the available evidence and its judgment, the committee identified factors considered to have the potential to contribute to the highest risks from the use of unencapsulated EAF slag and comprise key data needs. See Box S-1. A greater understanding of these factors will help ensure that calculated slag-related risks are not overestimated or underestimated. The relative importance of these factors is expected to differ on a case-by-case basis.

PRIORITY RESEARCH NEEDS

EPA should coordinate with state agencies, the National Slag Association, and other organizations to address these specific research needs:

Recommendation S.1: Building upon existing measurements, develop a database of slag chemical composition that is demonstrated to be a reasonable reflection of the variability in slag composition

across EAF steel plants in the United States. There should be clear documentation of where within the process the samples are taken. For consistency, it would be desirable for samples to be taken directly at the EAF. Ladle slag should be sampled to the extent it would be processed and sold for unencapsulated uses.

Recommendation S.2: Persistent organic pollutants, such as dioxins, are toxic chemicals that take a long time to break down in the environment. The detection of several of these pollutants in EAF slag (albeit at relatively low concentrations compared to EPA’s soil screening levels used for site remediation planning) indicates a need for further study. Assess the extent to which persistent organic pollutants should be included as target analytes in sampling production processes and downstream locations for site-specific risk assessments of EAF slag. Analysis at point of sale or use should be used to assess whether there is a problem at all.

Recommendation S.3: For unencapsulated slag that has weathered in place, obtain additional information on the following:

- Effects of weathering on the particle size distribution, and

- Potential long-term effects of high pH and trace elements in water leached from weathered slag into various surface and subsurface environmental conditions.

Recommendation S.4: To develop a better understanding of how concentrations and bioavailable fractions of hazardous slag constituents might change over time, conduct studies to characterize a wider range of weathered EAF slag materials and environmental conditions. Assessment approaches should include the following:

- Use of site-specific data, rather than estimates from the literature, before applying adjustments to standard default exposure factors and modifiers applied to regulatory toxicity values.

- Characterizing risk assessment scenarios for which slag covers all or most of a residential yard, slag dust is tracked into a house, and uptake may occur in home-produced foods.

- Exposure factors and sufficiency of uncertainty factors in derivation of toxicity values to account for susceptible life stages (during pregnancy, early in life, during childhood and adolescence, and in old age) and relevant pre-existing health conditions.

- Cumulative exposures to chemical and nonchemical stressors for cases where slag could likely be used around residences in disadvantaged communities. When quantification of those exposures is not feasible, qualitative descriptions should be used to summarize expected exposures in addition to those from slag.

Recommendation S.5: Pursue longer-term objectives to improve an understanding of metal toxicity, specifically the following:

- There are insufficient epidemiological studies of the health effects of environmental exposures to hexavalent chromium to exclude the risk of noncancer disease endpoints in susceptible populations at the important life stages of development and advanced age.

- Relationships between human health effects and environmental manganese exposures, including the following:

- Associations between intracellular manganese concentrations and genetic variants related to the regulation of manganese homeostasis and susceptibility to manganese-related neurotoxicity, and

- Effects of manganese as a modifier of disease severity or the rapidity of disease progression.

- A comprehensive re-evaluation of the toxicological and epidemiological literature for manganese is needed. EPA should update the Integrated Risk Information System

- toxicological review of manganese, which had not been significantly updated since the 1990s, and the Agency for Toxic Substance and Disease Registry should update its 2012 Toxicological Profile for Manganese.

- Delineation of potential health effects associated with exposure to high-hazard chemicals of potential concern, in addition to hexavalent chromium and manganese, for consideration in future risk assessments.