Health Risk Considerations for the Use of Unencapsulated Steel Slag (2023)

Chapter: Appendix E: Slag Mineralogy

Appendix E

Slag Mineralogy

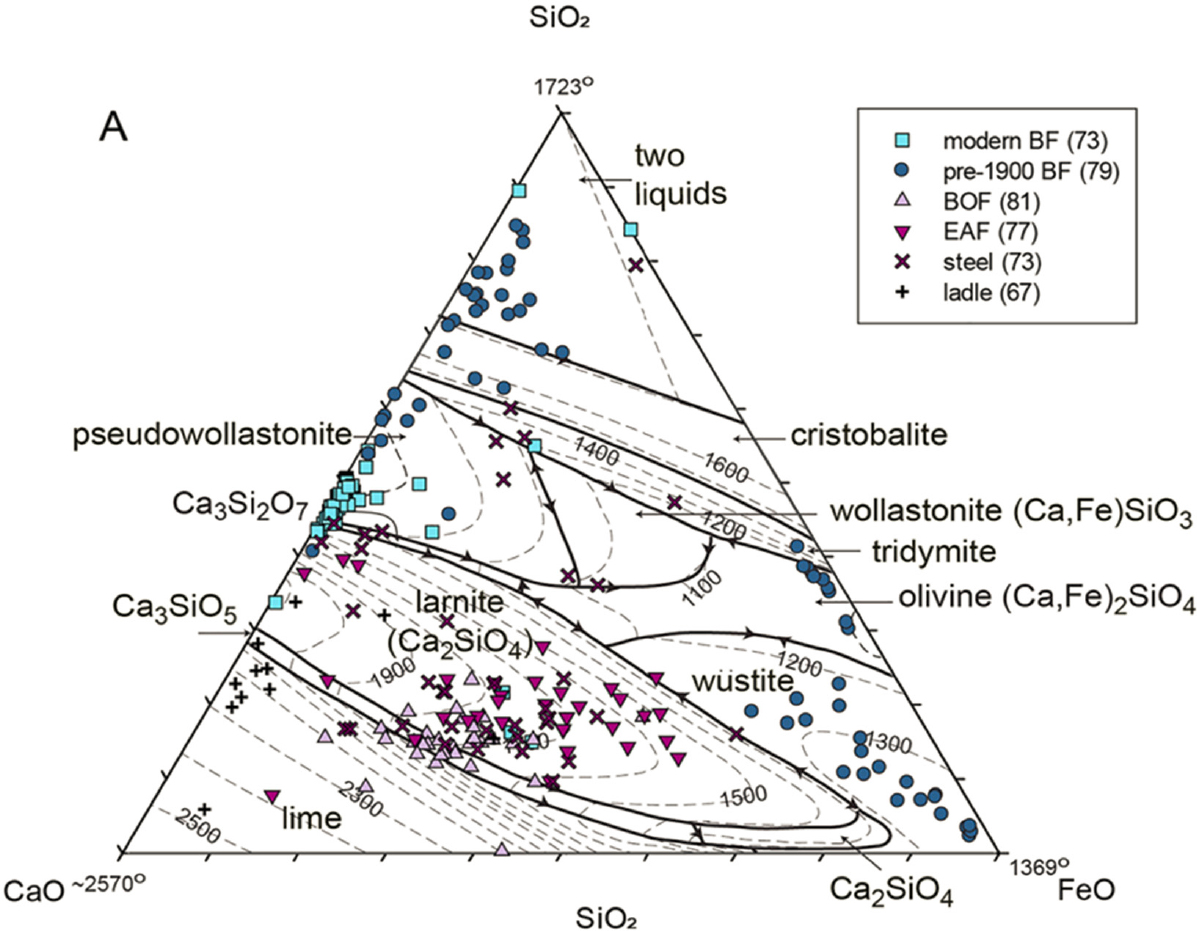

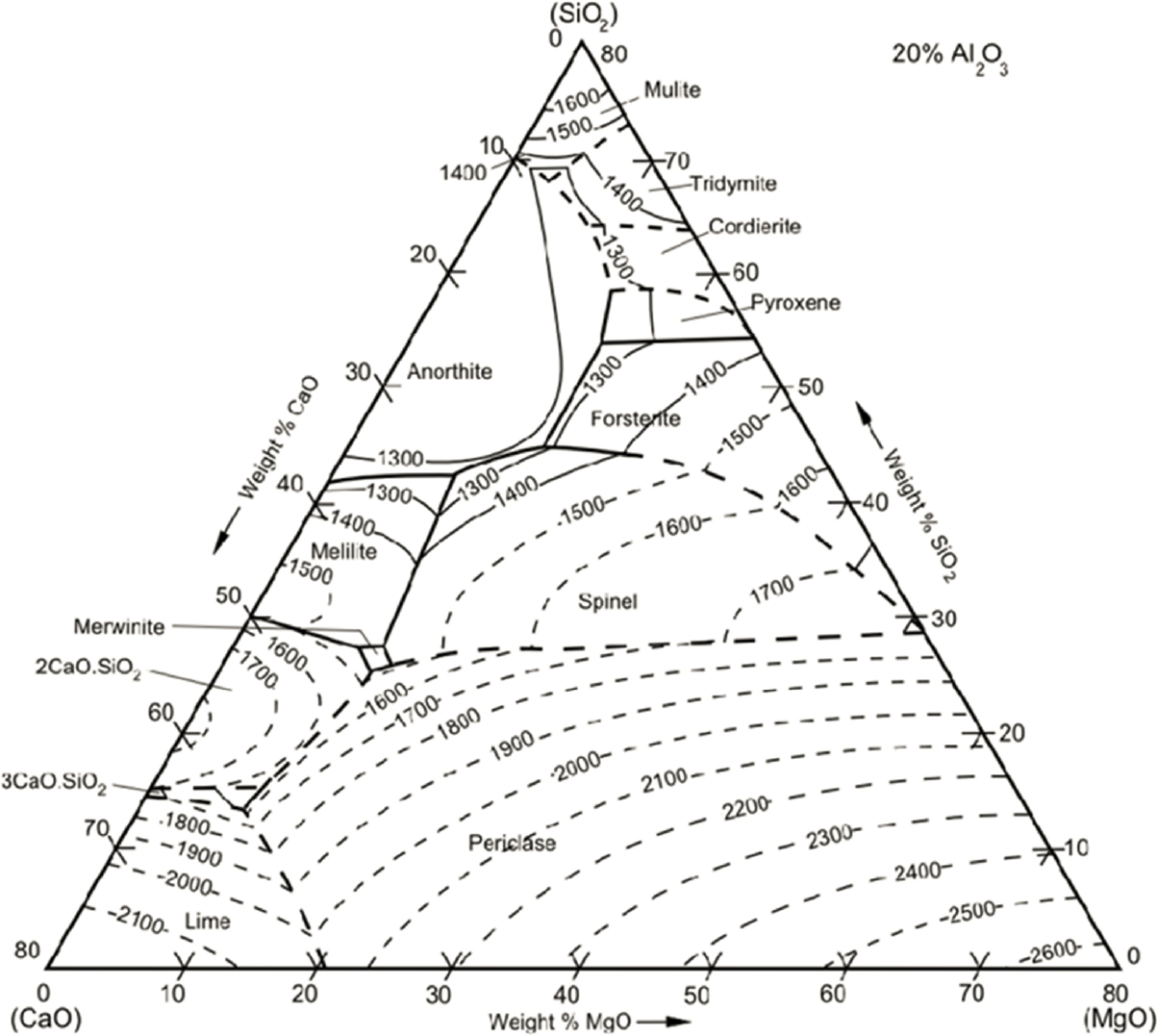

Basic slag mineralogy does roughly conform to the thermochemical dictates of phase equilibrium. The list of primary phase fields of mineral crystallization in liquidus diagrams within the system FeO-CaO-MgO-Al2O3-SiO2 (Figures E-1a and E-1b) shows some overlap with the list of minerals found in slags (Table E-1). The outstanding feature of the topography of the liquidus diagram in Figure E-1a is the thermal trough of minimum melting temperatures, which runs diagonally across the diagram at a CaO/SiO2 of about 1.2 from approximately the rankinite composition, Ca3Si2O7, to wustite, FeO. This indicates that ferrous oxide can be considered a contributory flux, a strategy in 19th century iron production. However, to follow this path reduces the yield of Fe to the pig iron by partitioning metal into oxidized slag. Under the strongly reducing conditions of blast furnace smelting, this wasteful partitioning of Fe to the slag is avoided, so the desired decrease in melting point of the CaO-based flux is largely accomplished through the incorporation of (alumino)silicates to a rough CaO/SiO2 basicity ratio of 1.1–1.3 to access the low-melting trough. To judge from the liquidus diagram of Figure E-1a, the expected major phases to crystallize would be larnite, rankinite, wollastonite, and wustite—minerals indeed found in slags. However, rankinite and wollastonite are rare in slags. This rarity can be understood with reference to Figure E-1b, in which Al2O3 had been added as a component to the MgO-for-FeO substituted base diagram of Figure E-1a. Rankinite and wollastonite disappear from the liquidus crystallization surface and melilite, spinel, and merwinite appear instead. Melilite is stabilized as a common slag mineral, compared to rankinite and wollastonite, by Al2O3. Larnite or any of its orthosilicate (Mg-stabilized) cousins, like belite, bredigite, merwinite, monticellite, and olivine, are expected and encountered in slag crystallization products. Note that merwinite and melilite appear to be in reaction to liquid with falling temperature in Figure E-1b, so their preservation after crystallization is not an equilibrium feature of slag crystallization. Likewise the preservation of silica in slags has no basis in the equilibrium crystallization of liquid with CaO/SiO2 near 1.1 and is thought to represent undigested flux in the case of quartz, or to be a refining byproduct of Si metal addition to deoxygenate steel in the case of cristobalite.

TABLE E-1 Slag Minerals Grouped by Chemical Type

| Mineral | Abbreviation | Formula | Cement Notation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple oxides | ||||

| Lime | Lm | CaO | C | Decarbonation product of CaCO3 in burnt lime |

| Periclase | Per | MgO | M | Can crystallize from dolomite/olivine fluxed liquids; solution with Wus |

| Wustite | Wus | FeO | F | Incomplete reduction of ore or Fe-loss in BOF decarburization |

| Manganosite | Mng | MnO | In solution with magnesiowustite from BOF; 2+ Mn oxide | |

| Quartz | Qz | SiO2 | S | Leftover flux reactant |

| Cristobalite | Crs | SiO2 | S | Deoxygenation refining |

| Corundum | Crn | Al2O3 | A | Deoxygenation refining |

| Ca-(Mg-Fe-Mn) silicates | ||||

| Wollastonite | Wo | CaSiO3 | CS | Pyroxenoid |

| Diopside | Di | CaMgSi2O6 | CMS2 | Pyroxene in ladle slags |

| Mineral | Abbreviation | Formula | Cement Notation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rankinite | Rnk | Ca3Si2O7 | C3S2 | Sorosilicate, replaced by melilite in aluminous slag |

| Larnite | Lrn | Ca2SiO4 | β-C2S | Orthosilicate group including olivine nesosilicates, Lrn = modest T |

| Belite | Bel | Ca2SiO4 | γ-C2S | Low-T, high-volume polymorph by inversion below 500 °C |

| Bredigite | Bre | Ca7MgSi4O16 | α-C2S | High-T Mg from dolomite, olivine, or/and refractory lining |

| Merwinite | Mw | Ca3MgSi2O8 | ||

| Monticellite | Mtc | CaMgSiO4 | ||

| Forsterite | Fo | Mg2SiO4 | Mg-Fe olivine flux ingredient or serpentine dehydration | |

| Fayalite | Fa | Fe2SiO4 | Solution with Fo | |

| Kirschsteinite | Kir | CaFeSiO4 | Solution with Lrn | |

| Glaucochroite | Gc | CaMnSiO4 | Solution with Lrn | |

| Hatrurite | Ca3SiO5 | C3S | Industrial mineral: alite | |

| Ca-Al silicates | ||||

| Anorthite | An | CaAl2Si2O8 | Feldspar, tectosilicate. Al from gangue or coke/coal ash or Al processing | |

| Ca Tschermak’s Cpx | CaTs | CaAl2SiO6 | Kushiroite in meteorites | |

| Melilite | Gh-Ak | Ca2Al2SiO7-Ca2MgSi2O7 | Sorosilicate, principal Al host | |

| Spinels and mixed oxides | ||||

| Spinel-hercynite | Spl-Hc | (Mg,Fe)Al2O4 | ||

| (Magnesio) chromite | (M)Chr | (Mg,Fe)Cr2O4 | Major 3+ Cr host | |

| Mg ferrite-magnetite | Mfr-Mag | (Mg,Fe)Fe2O4 | ||

| Maghemite | Mgh | γ-Fe2O3 | ||

| Galaxite | Glx | MnAl2O4 | 2+ Mn spinel component, not rock salt structure like Mng | |

| Hausmannite | Hsm | MnMn2O4 | 2+ and 3+ Mn spinel, Mag analog | |

| Ramsdellite | MnO2 | 4+ Mn oxide: marcasite structure; weathers to groutellite | ||

| Ca Vanadate | CaV2O7 | 5+ V in Ca-V oxide | ||

| Perovskite | Prv | CaTiO3 | ||

| Ca ferrite | CaFe2O4 | CF | ||

| Srebredolskite | Ca2Fe2O5 | C2F | ||

| Brownmillerite | Ca2FeAlO5 | |||

| Mayenite | Ca12Al14O33 | |||

| Tricalcium phosphate | Ca3(PO4)2 | Produced during pretreatment or refining | ||

| Mineral | Abbreviation | Formula | Cement Notation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal(oids) | ||||

| Metal | Fe | Failed separation from slag | ||

| Ferrochrome | FeCr | |||

| Oldhamite | CaS | Desulfurization product: Mn in solution | ||

| Alabandite | MnS | Desulfurization product: Ca in solution | ||

| Weathering products | ||||

| Portlandite | Ca(OH)2 | Hydration of lime; dissolution and hydration of C2S | ||

| Brucite | Brc | Mg(OH)2 | Hydration of periclase | |

| Calcite | Cal | (Ca,Mn)CO3 | Decomposition of C2S constituents to carbonate and silica | |

| Dolomite | Dol | CaMg(CO3)2 | ||

| Siderite | Sd | FeCO3 | ||

| Calcium silicate hydrate | Ca3Si2O7·3-4H2O | CSH | Variable composition and structure related to tobermorite | |

| Groutellite | MnO2 | Mixed valence version of Ramsdellite with 3+ and 4+ Mn and hydroxyl | ||

| Birnessite | Bir | (Na,Ca)0.5(Mn4+,Mn3+)2 O4 · 1.5H2O | Mixed valence, layered hydrous oxide of Mn | |

| Vernadite | Vnd | (Mn4+,Fe3+,Ca,Na)(O,O H)2 · nH2O | Layered manganate oxyhydroxide | |

| Todorokite | Tdr | (Na,Ca,K,Ba,Sr)1-x(Mn,Mg,Al)6O12 · 3-4H2O | Tunnel structured manganate hydrate | |

| Hollandite | Hol | Ba(Mn4+6Mn3+2)O16 | Tunnel structured mixed valence oxide | |

| Maghemite | Mgh | γ-Fe2O3 | Isostructural oxidation of magnetite, metastable | |

| Hematite | Hem | α-Fe2O3 | Stable rhombohedral form | |

| Fe-Al Oxyhydroxides | HFO | Complex ensemble | ||

| Ettringite | Ca6Al2(SO4)3(OH)12·26 H2O | |||

| Gypsum | Gp | CaSO4·2H2O | ||

| Bobierrite | Mg3(PO4)2·8H2O | |||

| Brushite | CaHPO4·2H2O | |||

| Whitlockite | Wht | Ca9Mg(PO4)6(PO3OH) | ||

NOTE: Most important minerals in boldface.

NOTE: The compilation is projected into the CaO-FeO-SiO2 subsystem of the larger composition space in which slags reside. Modern blast furnace (BF) slags are largely confined to the CaO-SiO2 subsystem, reflecting the excellent retention of Fe into metal in the strongly reducing atmosphere of the blast furnace charged with carbon reductant. Legacy BF slags of a century or more ago tended to have poorer control of the redox with significant FeO joining the slag unless the slag was siliceous, in which case the FeO content was bimodal high and low for different slags. The high dispersion of slag analyses within each group is noteworthy, as is the dispersion shown between groups. Electric arc furnace (EAF), ladle, and basic oxygen furnace (BOF) slags are richer in FeO, on average, than modern BF slags reflecting carbon, silicon, phosphorus, and other impurity removal using oxygen and/or argon–oxygen gas mixtures that will also add FeO to the slag. The primary crystallization fields suggest that EAF, ladle, and BOF slag crystallization should show much larnite, other orthosilicate olivine group minerals, and wustite in the solidification products. Table E-1 confirms this expectation.

SOURCE: Piatak et al. (2021).

The presence of Al in the slag will stabilize melilite and spinels in the crystallization products.

SOURCES: Bielefeldt et al. (2013) and Osborn et al. (1954).

REFERENCES

Bielefeldt, W. V., A. C. F. Vilela, and N. C. Heck. 2013. Evaluation of the Slag System CaO-MgO-Al2O3-SiO2. p. 176-185. In: 44º Seminário de Aciaria, São Paulo, Brazil. DOI 10.5151/2594-5300-22764.

Osborn, E. F., R. C. DeVries, K. H. Gee, and H. M. Kraner. 1954. “Optimum composition of blast furnace slag as deduced from liquidus data for the quaternary system CaO-MgO-Al2O3-SiO2.” Journal of Operations Management 6(1):33–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03397977.

Piatak, N. M., V. Ettler, and D. Hoppe. 2021. “Chapter 3: Geochemistry and mineralogy of metallurgical slag.” In Metallurgical Slags: Environmental Geochemistry and Resource Potential, edited by N. M. Piatak and V. Ettler, 59–124. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry.