Health Risk Considerations for the Use of Unencapsulated Steel Slag (2023)

Chapter: 4 Human Exposure to Unencapsulated Electric Arc Furnace Slag

4

Human Exposure to Unencapsulated Electric Arc Furnace Slag

People are exposed to numerous chemical pollutants and other stressors from a wide array of sources through multiple pathways. In general, stressors are defined as any physical, chemical, social, or biological entity that can produce a change in health, well-being, and quality of life. An exposure pathway is a link between a stressor and a receptor (humans or other organisms).

Assessment of human exposure to chemicals involves consideration of concentrations of chemicals in food, air, water, soil, and on surfaces that come into contact with individuals; pathways the chemicals take from their source to exposed persons; and the exposure route (how chemicals enter the body). Exposure assessment also involves gathering demographic information and patterns of human activity over time that may affect the intake of the chemical. For example, children and adults can be exposed to chemicals in the soil of residential properties by inadvertently swallowing or inhaling soil particles while carrying out various activities.

In the context of risk assessments of electric arc furnace (EAF) slag, exposure assessment plays a role in the identification of hazardous slag components (i.e., which constituents in slag may drive human health risks) and estimates of total long-term average daily doses of those components used in quantifying risk. Dose is generally defined as the amount of a chemical that enters a body during some amount of time. While an exposure assessment of unencapsulated slag is likely to share many of the same approaches as exposure assessments of contaminants in soil and dust, there may be some notable differences. Several specific topics included in the committee’s statement of task (see Box 1-1 in Chapter 1) are relevant to exposure assessment:

- Environmental pathways, exposure routes (ingestion, inhalation, dermal contact), and scenarios expected to be most important in evaluating exposure to chemicals of potential concern (COPCs) in slag;

- Possible effects of the formation of smaller sizes of particulate matter (PM) of slag with respect to exposure areas;

- Population subgroup characteristics and human developmental stages expected to be associated with the highest sensitivity to exposure to EAF slag constituents; and

- Relationships between slag uses and human health risk, including consideration of factors such as land use settings, human behavior, geographic areas, and local climate that may lead to the highest risks.

In focusing on human exposure assessment, this chapter discusses a conceptual site model (CSM) to illustrate pathways and routes by which humans can be exposed to slag COPCs, and equations, exposure variables, and default (recommended) parameter values that are consistent with U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) risk assessment guidance (e.g., EPA, 2011, 2014, 2019b). Specific exposure variables are identified for which there may be greater uncertainty in applying EPA-recommended default parameter values to slag exposure scenarios. In addition, the concepts of bioaccessibility and bioavailability are discussed.

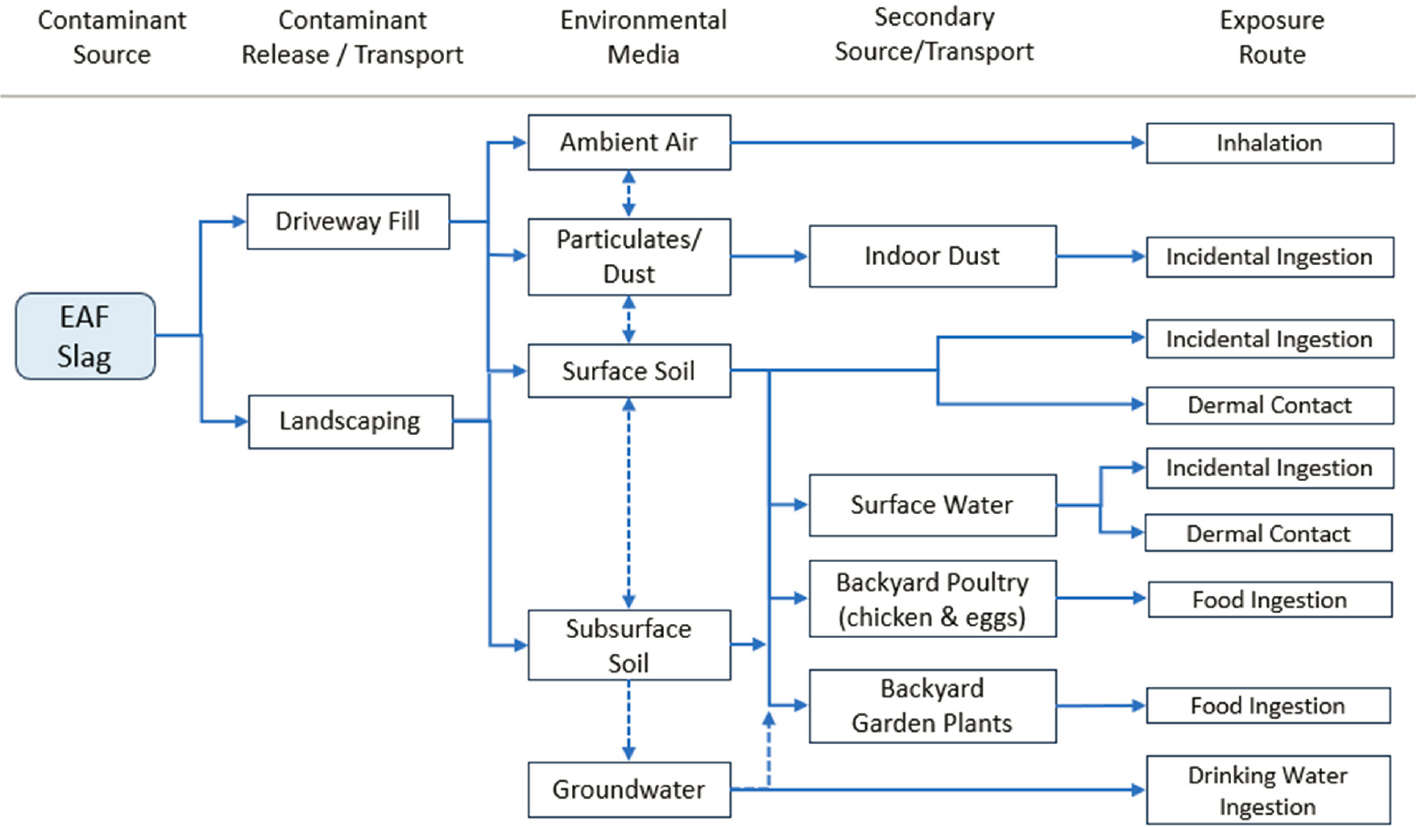

CONCEPTUAL SITE MODEL

A CSM identifies the potential sources and release mechanisms of COPCs and identifies the primary exposure points, receptors, and exposure routes evaluated in a human health risk assessment. Figure 4-1 shows a generic model that may apply to sites where EAF slag is used in an unencapsulated manner in a residential setting, such as for driveway cover or yard landscaping. The figure is provided as an example

for discussion purposes. The actual model at each site will depend on numerous factors, including the amount and type of slag used, human activity patterns, and local soil and climate conditions. A residential scenario was selected as an illustrative example because beneficial reuse of EAF slag includes fill material in residential settings, and risk-based soil screening levels developed by EPA and other agencies are typically lowest for residential scenarios to protect sensitive receptors (e.g., young children). The following factors are likely to be relevant to most residential use scenarios for EAF slag:

- PM may be generated and contribute to the indoor dust reservoir, where incidental ingestion occurs, particularly among toddlers.

- Outdoor contact with slag or slag mixed with soil may result in incidental ingestion and dermal contact.

- Inhalation exposure may occur, depending on the particle size distribution of slag and extent of areas where slag is applied.

- Slag used in landscaping could contribute to human exposure from home-produced foods, such as poultry (i.e., chicken meat and eggs) and garden fruits and vegetables that transfer slag contaminants to humans.

- Transport of contaminants through the soil column (i.e., horizontal and vertical transport) may contribute to contamination of groundwater or surface water, resulting in potential exposures via ingestion and/or dermal contact.

This figure includes the potential soil-to-groundwater (or surface water) transport pathway and corresponding human exposures through uses of household drinking water or recreation. This environmental transport mechanism may also be relevant at sites where receiving water is classified for

residential or agricultural uses, the soil has limited buffering capacity, and the depth to groundwater is relatively shallow. (See Chapter 3 for a discussion of the potential for COPC leaching and mobilization from EAF slag applied to soil.) Slag can contribute high pH leachate and contaminants to groundwater or surface water, in addition to impacts on water quality; exposure routes such as drinking water ingestion and food ingestion via irrigation with contaminated water could occur.

To formulate exposure parameters, assessments need to identify the relevant routes of exposure, time characteristics, sensitive subpopulations, and the intrinsic biological and extrinsic exposure factors, as well as potential confounders related to each outcome being assessed. Once these aspects have been recognized and defined, assessments need to determine whether the exposure parameters can be quantified for use in dose equations or whether they have to be addressed qualitatively. While quantifiable exposure parameters are optimal for calculations, the available data may not reliably represent the exposures of populations of interest.

AVERAGE DAILY DOSE EQUATIONS

As a general approach, slag exposure assessments can use the same set of standard dose equations recommended by EPA in Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund (RAGS) used to evaluate contaminants in soil and dust (EPA, 1989, 2019b). This includes calculation of the long-term average daily dose for ingestion and dermal contact routes and the calculation of a long-term exposure concentration in air for the inhalation route. To evaluate noncarcinogenic effects, the exposure duration and averaging time represent the same period and dose expressed as an average daily dose or average daily inhalation exposure concentration. To evaluate excess lifetime cancer risk, long-term exposures are averaged over a lifetime to yield a lifetime average daily dose. For toxicants that can cause cancer through a mutagenic mode of action, EPA recommends additional age-dependent adjustment factors to estimate potential increased susceptibility during early periods of human development (EPA, 2005a).

While both site-specific and default (EPA-recommended) exposure factors conventionally used to evaluate soil and dust exposures may or may not apply to slag, the general equations are applicable. Standard dose equations that yield estimates of administered dose associated with direct contact and indirect exposure pathways (via food) commonly considered in risk assessments involving exposure to residents or workers are presented in the following sections.

Incidental Ingestion of Slag COPCs

The following equation for the slag ingestion route was adapted from the equation for soil and sediment exposures given in RAGS (Volume 1) Part A (EPA, 1989):

where

| ADDing,slag | = average daily dose from incidental ingestion of slag (mg/kg-day), |

| Cslag | = concentration of COPC in slag (mg/kg), |

| CF | = mass conversion factor (10-6 kg/1 mg), |

| IR | = average daily ingestion rate of slag (mg/day), |

| RBA | = bioavailability (defined later in this chapter) from slag relative to bioavailability from dose medium used to derive the toxicity value, |

| EF | = exposure frequency (days/year), |

| ED | = exposure duration (years), |

| AT | = averaging time (days), |

| BW | = body weight (kg). |

Dermal Contact with Slag

The following equation for the dermal contact pathway was adapted from RAGS (Volume 1) Part E (EPA, 2004):

where

| ADDd | = average daily dose from skin contact with soil or sediment (mg/kg-day), |

| Cslag | = concentration of COPC in slag (mg/kg), |

| CF | = mass conversion factor (10-6 kg/1mg), |

| EV | = event frequency for contact with slag (events/day), |

| SA | = skin surface area available for contact with slag (cm2), |

| AF | = skin surface adherence factor for slag (mg/cm2-event), |

| ABSd | = dermal absorption fraction (unitless), |

| EF | = exposure frequency (days/year), |

| ED | = exposure duration (years), |

| AT | = averaging time (days), |

| BW | = body weight (kg). |

Inhalation of Slag

The following inhalation exposure concentration equation was adapted from RAGS (Volume 1) Part F1:

where

| ECair | = average daily inhalation exposure concentration in ambient air (µg/m3), |

| Cair | = concentration of COPC in ambient air (µg/m3), |

| EF | = exposure frequency for area with slag (days/year), |

| ED | = exposure duration (years), |

| ET | = exposure time spent in air with slag (hours/day), |

| CF | = time conversion factor (1 day/24 hours), |

| AT | = averaging time (days). |

For metals and nonvolatile organic compounds, Cair may be estimated using a particle emission factor:

where

| Cair | = concentration of COPC in ambient air (µg/m3), |

| Cslag | = concentration of COPC in slag (mg/kg), |

| CF | = mass conversion factor (1,000 µg/1 mg), |

| PEF | = particulate emission factor (m3/kg). |

___________________

1 See https://www.epa.gov/risk/risk-assessment-guidance-superfund-rags-part-f.

In addition to these direct contact exposure routes, indirect exposure may also occur through uptake in home-grown food (HGF), such as poultry (e.g., chicken meat and eggs) and garden fruits and vegetables. This may be particularly relevant if soil regional screening levels (RSLs) are applied to screen EAF slag material that is used to amend gardening soil, given that RSLs do not account for these additional exposure pathways.2 Alternative, site-specific screening levels and/or a full baseline risk assessment could be applied if the food ingestion pathways are included in a CSM.

Home-Grown Food

The general intake equation for the ingestion of both backyard garden fruits and vegetables and home-raised poultry (such as chicken meat and eggs) is as follows:

where

| ADDHGF | = average daily dose from home-grown food consumption (mg/kg-day), |

| CHGF | = concentration of COPC in food product (mg/kg), |

| CF | = mass conversion factor (10-3 kg/1 g), |

| IRHGF | = average daily ingestion rate of home-grown food product (g/day), |

| RBA | = bioavailability from home-grown food relative to bioavailability from dose medium used to derive the toxicity value, |

| EF | = exposure frequency (days/year), |

| ED | = exposure duration (years), |

| AT | = averaging time (days), |

| BW | = body weight (kg). |

Typically, IRHGF represents a long-term average ingestion rate during the course of a year, so the exposure frequency is 365 days a year. In addition, the concentration in HGF can be measured or modeled using a soil-to-plant uptake factor (also called a bioaccumulation factor or BAF); however, the extent to which literature-based soil-to-plant uptake factors may apply to EAF slag is not known.

BIOACCESSIBILITY AND BIOAVAILABILITY

The entire intake (average daily dose) of a COPC in slag may not reach the site within a person’s body where the chemical could cause a harmful effect. For example, if a child ingests a mixture of soil and slag particles, some amount of the COPC would transfer from the soil or slag particle in the gut, cross the intestinal barrier, enter the blood stream, and reach a target organ. The extent to which a COPC that is bound to the slag matrix or soil particles is available to cause harm involves consideration of the bioavailability and bioaccessibility of the COPC.

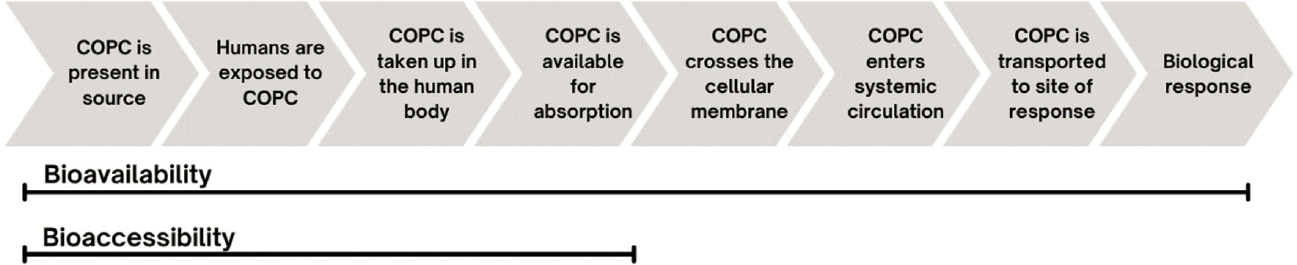

The committee notes there are differences in definitions and uses of the terms “bioavailability” and “bioaccessibility” across scientific disciplines, technical fields, and regulatory policies and guidance. For example, in some cases, bioaccessibility and bioavailability are defined as distinct, sequential terms (EPA, 2007a) rather than interchangeable synonyms. For purposes of this report, the committee adopted the conceptual framework shown in Figure 4-2.

Following this conceptual framework, the committee used the following definitions of bioaccessibility and bioavailability:

___________________

2 See https://www.epa.gov/risk/regional-screening-levels-rsls.

- Bioaccessibility embodies the first four of the eight steps shown in Figure 4-2: it covers the release of the COPC from an environmental matrix up to the point at which the COPC is able to cross a cellular membrane.3 This definition includes the extent to which the COPC is soluble in a biological matrix (e.g., gastrointestinal fluid), thereby having the capability to be absorbed into a cellular membrane (e.g., gastric epithelium). This construct does not encompass the actual uptake of the COPC through such a membrane.

- Bioavailability goes beyond bioaccessibility by adding the steps within the human body, as the COPC crosses a cellular membrane and proceeds through mechanisms that may result in adverse health responses. Bioavailability identifies the entire course of the COPC’s release from an environmental matrix to human health responses caused by the absorbed COPC. Therefore, bioavailability includes the fraction of the dose within the human body that becomes available for systemic distribution to target sites (e.g., lung, stomach), where harmful health impacts may occur.4

Bioavailability may be expressed in absolute and relative terms (EPA, 2007b). Absolute bioavailability is the percentage of the dose that is absorbed and reaches systemic circulation; this measure cannot exceed 100 percent and often is less. Relative bioavailability (RBA) is a ratio of the bioavailability of a substance present in an exposure matrix (e.g., soil) to the bioavailability of the substance in the matrix used in the critical toxicity study (e.g., food) (NRC, 2003). If the COPC is readily extractable by gastric fluid, all or a large portion of the dissolved COPC may be readily transferred across a cellular membrane. When the COPC is less soluble than in the critical toxicity study (e.g., an animal model), the RBA may be less than 1, indicating that the absorbed dose from soil is expected to be lower than the absorbed dose from the toxicity study for the same unit concentration in the exposure matrix. Because of its role in the interpretation of dose–response relationships, RBA can be an influential variable in a risk assessment. In the absence of site-specific data, EPA typically applies a health-protective assumption that RBA is 1 for most contaminants for which RSLs for soil have been developed,5 including chromium and manganese. Bioavailability and, more broadly, factors affecting biokinetics (i.e., absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination, or ADME) and potential toxicity of chromium and manganese are further discussed in Chapter 5.

KEY EXPOSURE VARIABLES FOR FURTHER EVALUATION

Consistent with EPA guidance, exposure assessments involving contact with soil and dust typically include calculations to represent the reasonable maximum exposure (RME) and central tendency exposure (CTE) scenarios. An RME is intended to represent the “highest exposure that is reasonably expected to

___________________

3 See https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pha-guidance/glossary/index.html#B_definitions.

4 Ibid.

5 See https://www.epa.gov/risk/regional-screening-levels-rsls.

occur at a site” (EPA, 1989). Risks calculated for the RME scenario are considered the high end (95th percentile) of the distribution for the defined population (EPA, 2001, 2014). Exposure parameter values used for the RME scenario are typically a mix of upper percentiles (90th or 95th percentiles) and arithmetic means or medians, whereas the CTE scenario is based exclusively on means or medians (EPA, 2000).

One of the approaches used in risk assessment to account for differences in exposure across life stages is to evaluate exposures to receptors of different ages. Age is a useful proxy variable that accounts for human variability in activity patterns and behaviors, ingestion rates, anatomy, and physiology (EPA, 2005a). The average daily dose for young children can often be higher than that for older children and adults when expressed on a body weight-normalized basis. Furthermore, for some chemicals, individuals may be more susceptible to adverse health effects if exposure occurs during early development (infancy and early childhood) as discussed in Chapter 5. To promote consistency in risk assessment methodology, EPA has historically recommended specific age group categories that should be considered for exposure monitoring and assessment, and it provides recommended default exposure parameters to facilitate the calculation of average daily dose over various age ranges (EPA, 2011, 2014, 2019b).

The committee considered whether the basis for EPA-recommended RME values typically used for exposure assessments involving contact with soil and dust are reasonable to apply to EAF slag, given both the expected uses of slag in residential settings and the difference between soil and slag as an exposure matrix. Aside from the concentration terms, key exposure variables that likely warrant consideration can be grouped by non-chemical-specific factors and chemical-specific factors (see Table 4-1).

TABLE 4-1 Key Exposure Variables in Exposure Assessments of Slag

| Group | Key Exposure Variable | Source of Variability and Uncertainty |

|---|---|---|

| Non-chemical-specific | IR, average daily ingestion rate of slag (mg/day) |

|

| EV, event frequency of contact (events/day) |

|

|

| AF, skin surface adherence factor (mg/cm2-event) |

|

|

| PEF, particulate emission factor (m3/kg) |

|

|

| Chemical-specific | RBA, relative bioavailability (unitless) |

|

| ABS, absorption factor, adjustment for dermal dose (unitless). It is the fraction of the chemical absorbed in gastrointestinal (GI) tract. |

|

|

| BAF (bioaccumulation factor), slag-to-plant uptake factor (mg COPC/kg tissue per mg COPC/kg soil) |

|

SUMMARY

The following are key conclusions regarding the exposure assessment of EAF slag presented in this chapter.

Based on the expected chemical composition and physical properties of unencapsulated EAF slag applied in the environment, and likely mixing of EAF slag particles and soil over time, potential exposure pathways and routes include incidental ingestion of slag particles mixed in outdoor soil and indoor dust, inhalation, and dermal contact.

Additional exposure pathways for consideration include ingestion of home-produced foods grown on properties with EAF slag and ingestion and dermal contact with surface water and groundwater. High pH water leached from slag can adversely affect the solubility and mobilization of contaminants from slag to groundwater.

When mixed with outdoor soil and indoor dust, EAF slag may alter the overall bioaccessibility and bioavailability of inorganic COPCs. Use of site-specific data would be preferable to using estimates from the literature to support adjustments to standard default exposure factors and modifiers applied to regulatory toxicity values.

Current data gaps regarding the range of unencapsulated EAF properties and uses warrant that caution be applied regarding generalizations about contaminant fate and transport as well as bioavailability.