Climate Security in South Asia: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 2 Climate, Development, and Security Challenges in South Asia

2

Climate, Development, and Security Challenges in South Asia

Workshop participants explored some of the underlying climate, development, and geopolitical dynamics at play in the South Asia region through a panel discussion with two invited experts. Dr. Joyashree Roy, the Director of the Centre on South and Southeast Asia Multidisciplinary Applied Research Network on Transforming Societies of Global South at the Asian Institute of Technology, shared an environmental and energy economics perspective on “Multidimensional Security Issues While Moving Towards a Decarbonised World.” Mr. Sarang Shidore, of the Quincy Institute, offered a geopolitical perspective on “Climate–Conflict Pathways in South Asia.”

SECURITY ISSUES ASSOCIATED WITH A LOW-CARBON ENERGY TRANSITION

Roy prefaced her remarks by noting that climate-related security risks stem from more than just the impacts of physical climate change on people and society; the societal transitions that occur in response to climate change can also create new security risks. As the international community seeks to accelerate and deepen its climate mitigation actions, she noted that a rapid transition to a low-carbon economy poses a particular set of risks to the security of developing regions. In her presentation, Roy explored the fundamental challenge of achieving a secure, sustainable, and just decarbonization transition within the regional circumstances and context of South Asia. Focusing her attention on the energy sector, she described the multidimensional security issues associated with decarbonization, explored the linkages between climate mitigation options and sustainable development goals, and highlighted opportunities to maximize the synergies between them.

___________________

1 This list is the rapporteurs’ summary of the points made by individual speakers, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

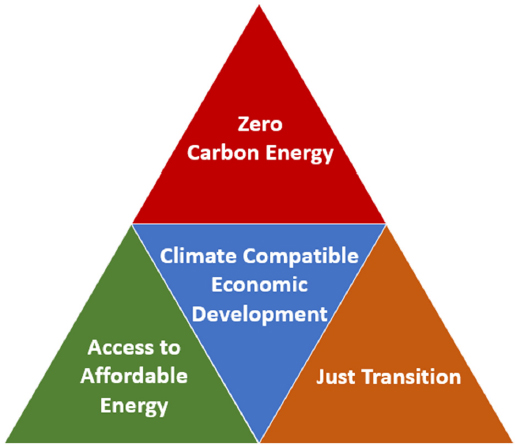

Roy argued that decarbonization must occur through a climate-compatible economic development pathway for South Asia that addresses a basic energy trilemma: how to create a low-carbon economy in a way that ensures (1) energy security (i.e., by maintaining a reliable and resilient energy system); (2) sustainability (i.e., by maximizing the climate and environmental benefits of energy policy); and (3) equity (i.e., by ensuring accessible and affordable energy across society) (Figure 2-1). In practical terms, this would involve managing the decarbonization transition through institutions and policies that can meet the growing demand for non–fossil fuel energy sources, avoiding job loss and building new skilled human capacity, and addressing the stranded assets of fossil fuel infrastructure. Roy argued that decarbonization must also balance its climate mitigation goals with the sustainable development priorities that are central to building and maintaining human and political security in South Asia. She noted that climate mitigation policies can interact positively (through synergies) or negatively (through trade-offs) with these development priorities.

Roy offered a few examples of how climate mitigation and sustainable development pathways could involve significant trade-offs. With respect to food and water security, she noted that mitigation policies emphasizing land-based carbon sequestration or water-intensive energy technologies could increase demands for land and water, displacing food crops and communal water supply. With respect to energy security, an emphasis on broad-based electrification could increase electricity demand and potentially reduce the affordability and accessibility of energy in poorer communities; an emphasis on nuclear energy generation could intensify risks related to radioactive waste; and policies emphasizing hydrogen could create risks related to fuel storage and transportation. Roy noted that the security risks related to these types of trade-offs would be expected to be more severe in geographies where human lives and livelihoods are impacted by general poverty, weak institutions, poor governance, and persistent inequity—where development needs are the greatest.

Roy noted that many of the interactions between mitigation policies and development priorities are knowable and foreseeable, and there is an opportunity and a strong need for scientific assessments that can effectively identify potential synergies in different geographic contexts. She cited recent work that explored the specific linkages between climate mitigation and sustainable development in South Asia and highlighted opportunities to maximize the development co-benefits of climate mitigation in the region. The Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH) assessment report, completed in 2019, considers plausible futures for the HKH region, which originates 10 major Asian river systems and supports the resource base and prosperity of 1.65 billion people directly downstream (Wester et al., 2019). In the most optimistic scenario, for a prosperous HKH, the region benefits from international climate finance commitments, as well as a portfolio of climate mitigation actions—particularly in the energy-demand and land-use sectors—that complement and support development goals. More broadly, the region realizes opportunities to strengthen its political and economic integration, innovate on technology, and improve cooperation both across and within national borders. Conversely, in the least optimistic, “downhill” scenario, the region fails to achieve a climate-compatible economic development pathway that addresses the challenges of poor governance, poor economic development, and political instability; in this scenario, socioeconomic conditions deteriorate as vulnerability to the impacts of climate change and environmental degradation increases.

Roy emphasized that climate mitigation and sustainable development synergies can be maximized by mitigation actions tailored to regional development circumstances and context. For the South Asia region, she cited her own ongoing research demonstrating particularly strong synergies on the energy-demand side that could be achieved through changes in infrastructure, including through the design of compact cities and efficient building spaces; sociocultural factors, including through dietary choices and changes in consumer behavior; and end-use technology adoption, such as the use of more energy-efficient appliances. Roy’s research indicates that demand-side solutions can substantially reduce upstream greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and energy use; moreover, many solutions are cost effective and involve off-the-shelf technologies (Creutzig et al., 2022).

Roy concluded her remarks by noting that the scientific assessment literature includes a significant knowledge gap on the interactions between climate and development challenges, as well as the potential solutions space. She noted that, in general, assessments do not holistically integrate mitigation pathways and development pathways. She also noted that many of the demand-side solutions for reducing climate emissions and energy use involve social and technical innovations at granular levels, which are not always integrated into the modeled pathways.

CLIMATE–CONFLICT PATHWAYS

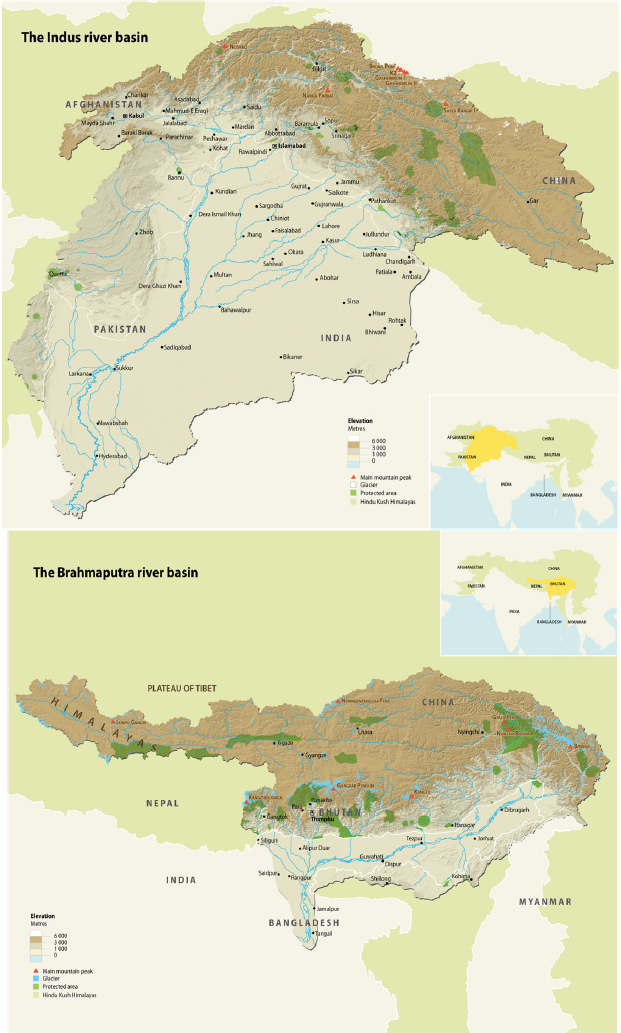

In his remarks, Shidore described South Asia as a crucible of climate security analysis and reflected on the region’s diverse climate hazards, varied security challenges, and the evolving understanding of the connections between them. He noted that research on the relationship between climate and conflict has produced some basic insights, but that much remains unknown about the pathways leading from climate change to violent conflict. In his presentation, Shidore briefly reviewed the current state of climate–conflict research and some of the key climate hazards in South Asia. He noted that conflict dynamics in the South Asia region can include civil war and militancy, national-level protests and social unrest, and localized conflicts at the scale of a village or a subnational region; however, he focused his remarks on three key interstate rivalries in the region: in the Indus River basin, between India and Pakistan; in the Brahmaputra River basin, between India and China; and in the India–Bangladesh–Myanmar corridor.

Shidore noted that research on climate and conflict has identified key climate influences, potential climate–conflict pathways, and mediating variables that can shape the security environment in South Asia. With respect to climate influences, shorter-term variability produces extreme conditions, including heatwaves, drought, intense rainfall, floods, and cyclones. Longer-term climate trends are projected to increase the frequency and intensity of these extremes, as well as produce other adverse conditions over time, such as lowered agricultural yields or degraded coastal communities. With respect to causal pathways, Shidore noted that one key pathway involves climate-related changes in critical resources such as food or water. He explained that either scarcity or abundance in a resource could pose security challenges, with an example of the latter being a situation where plentiful resources advantage one particular party in an existing conflict or result in contestation over access to that additional resource. Another key pathway involves climate-induced migration or displacement. Shidore pointed out that the climate–migration–conflict linkage is vigorously debated in the expert community, with basic questions still unanswered about the expected scale of migration under different climate scenarios, the respective roles of migrants and receiving communities in sparking conflict, and the extent to which this type of conflict actually engenders violence. With respect to mediating variables, Shidore pointed out that even in a setting where a clear causal pathway may exist, several factors can influence whether the adverse consequences of a climate extreme or disaster will include conflict. These include the presence of civic institutions, from subnational to international levels, that can effectively cope with the impacts of climate change; the capacity of national authorities to conduct humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) operations and provide services after a disaster; and the degree of harmony between different communities, ethnic groups, and social classes that can prevent fracturing along traditional fault lines in a crisis.

Shidore turned to an analysis of three specific interstate rivalries in the region. The first case was in the Indus River basin, between India and Pakistan (Shidore, 2020; see Figure 2-2). He explained that the distribution and management of the waters of the Indus and its tributaries is governed by the Indus Water Treaty, signed in 1960, which partitions the river system, with water from three rivers predominantly awarded to India and water from the other three to Pakistan. The treaty delineates rights and responsibilities for both countries, but Shidore noted that there are grey areas where contestation and disputes can occur and that this issue bedevils water management in this region. He also pointed out that India is the upstream actor in this system and that a fundamental feature of transboundary water disputes is that upstream actors have disproportionate power.2 Shidore noted that climate change is exacerbating existing challenges within the basin and creating opportunities for disputes. For example, he noted that the warming and melting of mountain glaciers will be spatially variable and have a differential impact on river flow rates across the basin. In the context of these evolving climate stressors, disputes over river development projects, as well as over general patterns of overconsumption and poor water management, have escalated. Shidore took stock of the prospects for the conflict dynamic between India and Pakistan. As a positive, he noted the existence of an international treaty that has survived wars and repeated contestation. On the negative side, however, he noted that there was significant distrust between the two nations since border skirmishes in 2016. He also noted that there are no effective peace-building institutions, noting that the South Asia Regional Cooperation is moribund. In addition, he noted the general challenges to peace posed by poor domestic governance and the challenges of poverty and poor infrastructure, especially in Pakistan.

___________________

2 Since some rivers flowing from India to Pakistan originate in or pass through Kashmir, a disputed region that has triggered multiple India–Pakistan wars, the Kashmir issue is a major reason why water disagreements between India and Pakistan are inherently securitized (see https://climate-diplomacy.org/case-studies/water-conflict-and-cooperation-between-india-and-pakistan).

Shidore’s next case study explored the dispute between China and India in the Brahmaputra River basin (Shidore et al., 2021; see Figure 2-2). He noted that China is the upstream actor in this system and has proposed a large hydroelectric power project larger than the Three Gorges dam. If

completed, its size creates opportunities for real or perceived manipulation of river flows and perceptions of bad faith at a time when there is already distrust between the two countries following recent territorial disputes along their border. In assessing the prospects for avoiding conflict in this situation, Shidore noted, as a positive, that the dispute is in its very early stages with opportunities for agreements to avoid future conflict. He also noted that the river is very large and is mostly undeveloped, and that the two countries do already cooperate through an existing, albeit limited, data exchange mechanism. On the negative side, however, Shidore noted that there is no treaty or other framework in place to manage disputes, or even any obvious mediators between these two countries who are generally sensitive about sovereignty issues and not welcoming of external interventions.

Shidore’s final case study focused on the India–Bangladesh–Myanmar corridor, which he characterized as a unique confluence of security problems. He noted that both eastern India and Bangladesh experience impacts from episodic political and communal violence, including an armed insurgency in the eastern Indian state of Chhattisgarh and refugees in Bangladesh escaping from violence in Myanmar, that exacerbates existing vulnerabilities in the region to climate hazards such as cyclones. Shidore laid out several climate-security scenarios that could transpire in a warming world. In the first, a “meltdown” in Myanmar due to political violence coincides with a tropical cyclone to produce a devastating humanitarian and security crisis for the region. In the next scenario, Bangladesh’s economic development and governance pathways, following recent trends of the country’s remarkable successes in these areas, are able to overcome its climate and security challenges, and the country correspondingly becomes a regional anchor and solutions provider. The third scenario involved a stalled Bangladesh due to climate challenges overwhelming positive trends, which then becomes a regional cautionary tale. In the final scenario, global impacts from climate change continue to grow, most countries become more inwardly focused, and international cooperation and assistance dramatically decreases. In this potential future, the most vulnerable countries and communities are no longer able to keep pace with the growing impacts from climate hazards.

Shidore concluded his remarks with perspectives on the opportunities to manage climate-related conflict in the South Asia region. He pointed out that opportunities to resolve disputes and contestation are severely constrained by the lack of regional cooperation or solutions mechanisms. Shidore also noted that China will play an important role in determining the region’s security future, as it controls the “Third Pole”3 of the Tibetan Plateau, where most of the region’s major rivers originate, but is not part of any major institutions relevant to environmental and resource management in the region. China is also a major actor in the climate mitigation space, particularly in the development of renewable energy technologies, and could be a solutions provider for the region. Finally, Shidore noted the “irony of solutions,” observing that many of the policy responses to climate risk may create their own adverse consequences for security and development in the region. For example, India’s push to decarbonize its energy sector may lead to contestation over land, tensions between federal and local governments over policymaking authority, and a potentially unjust transition that leaves workers and communities dependent on this fossil fuel sector stranded. Also, China’s motivation to develop hydropower resources is related to its own climate commitments but could spark disputes and conflicts that reduce climate resilience in the region. Shidore concluded by emphasizing that climate and security issues are tightly coupled arenas, with causality running both ways, and have multiple intervening variables, with institutions and capacity for cooperation as perhaps the most critical.

___________________

3 The Third Pole comprises the Tibetan Plateau and surrounding mountains, and it represents the largest masses of ice, snow, and permafrost outside of the Arctic and Antarctic regions.