Climate Security in South Asia: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 5 Tools for Analysis and Forecasting

5

Tools for Analysis and Forecasting

A panel of invited experts shared their perspectives and engaged workshop participants on the tools for analysis and forecasting that are currently available and what is missing for the South Asian context and beyond. Dr. Kanta Kumari Rigaud, of the World Bank, provided an environmental management and climate adaptation perspective on “Plausible Climate Migration Scenarios: Harnessing Data, Models, and Simulations.” Dr. Erin Coughlan de Perez, at Tufts University, offered a climate risk management perspective on “Impact-Based Forecasting.” Dr. Kathy Pegion, at the University of Oklahoma, shared her perspectives on “Tools for Climate Predictions and Projections.” Workshop planning committee member Dr. Virginia Burkett, of the U.S. Geological Survey, moderated the panel and facilitated a plenary discussion.

PLAUSIBLE CLIMATE MIGRATION SCENARIOS

Rigaud presented findings from recent work at the World Bank to develop scenarios for global climate migration in 2050. The effort was motivated by her earlier research showing that without concrete international action to address climate and development priorities, climate impacts by the mid-century could lead more than 216 million people across six global regions to migrate within their own countries (Clement et al., 2021). Her latest work was intended to support a constructive dialogue that could drive informed policies and actions at global and national levels to address the drivers of climate migration.

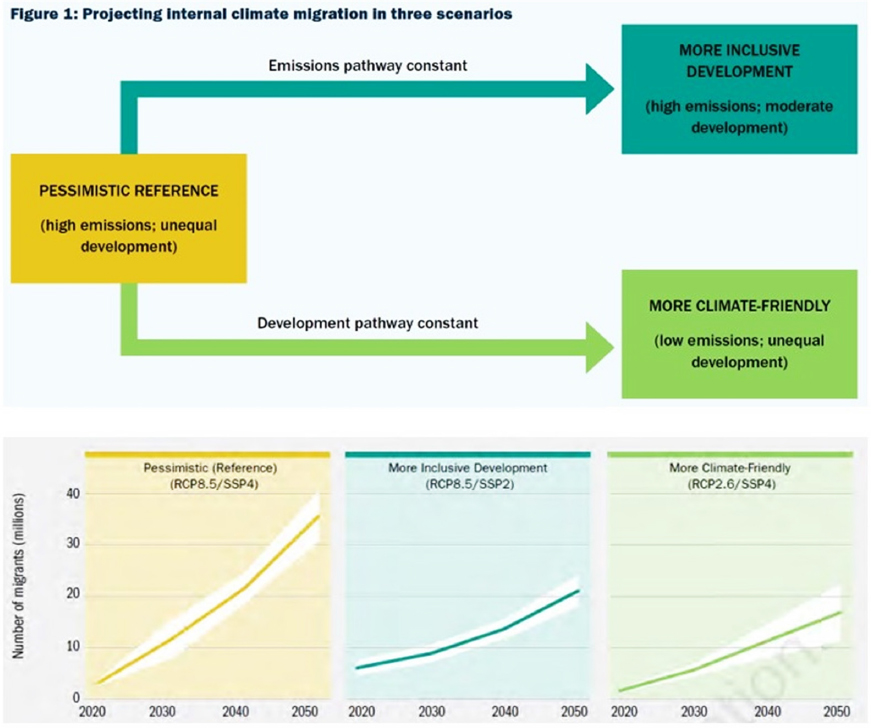

Rigaud described the scenario development process, which produced three plausible futures at the climate–migration–development nexus: a “pessimistic” reference case, in which emissions were high and development was unequal, and two more cases identical to the reference except with either a lower emission (i.e., climate friendly) or more inclusive development pathway (Figure 5-1). Rigaud described four basic questions the scenarios were intended to explore: how many climate migrants there might be by mid-century, where potential hotspots of movement might occur, the extent to which different climate futures would drive mobility, and the implications for medium- and longer-term development planning.

___________________

1 This list is the rapporteurs’ summary of the points made by individual speakers, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Rigaud shared the main takeaway messages from the study. With respect to total global numbers of climate migrants, the scenarios return a range of values: 44 million people under the climate-friendly pathway, to 216 million under the reference pathway. At the regional level, time series of total migrants show that the climate migration trajectory ramps up to 2050 virtually everywhere, with the steepest increases associated with the pessimistic scenario. In South Asia, Rigaud pointed out a sixfold increase in the number of total migrants. She noted that a window of opportunity exists early on to bend these curves, but that it is closing quickly. With respect to climate migration hotspots, the study indicated substantial heterogeneity over time, with some hotspots emerging as early as 2030 and spreading by 2050, and also across geographies, with hotspots clustering in subregions prone to climate hazards, particularly Bangladesh in the northeast (Clement et al., 2021).

Rigaud concluded her remarks by noting four key areas for action at the intersection of climate, migration, and development. They include dropping global GHG emissions to reduce the climate pressures that drive migration; integrating climate migration into far-sighted green, resilient, and inclusive development planning; planning for each phase of migration—before, during, and after—to ensure positive adaptation and development outcomes; and investing in understanding the drivers of climate migration. She reiterated that the window of opportunity to act is still open but not for long.

IMPACT-BASED FORECASTING

Coughlan de Perez offered a perspective focusing on shorter-term timescales and the forecasting approaches that can anticipate impacts from weather and climate events, as well as support humanitarian efforts. This forecasting addresses basic questions around what conditions public service providers, humanitarian organizations, and others can anticipate in the short term, and what actions can be taken ahead of a particular event. Coughlan de Perez described different technical approaches to answer these questions, focusing her attention on impacts more related to national security and conflict.

Coughlan de Perez described impact-based forecasting as a new way of framing weather forecasts from a risk perspective that examines the overlap of hazards, vulnerability, and exposure to produce risk. She explained that an impacts-based approach moves away from forecasting what the weather will be to what it will do—for example, where a flood is expected to inundate roads and homes and where emergency supplies can be pre-positioned. She provided examples of impacts-based forecasting efforts around the world that are providing this kind of detailed information to communities before they experience hazards. These include a UK Met Office effort to create national maps showing the expected locations of specific types of storm damage, and a partnership between the Mongolian Red Cross and government to develop a forecast-based financing system to identify vulnerable populations ahead of the winter season and provide assistance.

Coughlan de Perez also shared her perspectives on the future directions of impact-based forecasting, noting that compounding and cascading climate and weather events pose a particular challenge. She shared a typology of these events, identifying four general cases where the forecasting community needs to focus attention (adapted in Table 5-1). One type is preconditioned events, where an initial driver creates conditions that magnify impacts from a subsequent driver, such as when snowfall creates a snow-covered surface on which a subsequent heavy rainfall could produce greater flooding. A second type is multivariate events, where a modulating factor creates multiple drivers and/or hazards, such as when a La Niña event creates droughts and heatwaves. A third type is temporally compounding events involving sequential drivers in the same location, such as when repeated heavy rainfall events produce flooding. A fourth type is spatially compounding events, where a single modulating factor creates drivers and impacts in multiple regions at the same time, such as when an El Niño event leads to globally synchronized crop failures.

Coughlan de Perez pointed out the particular challenge that unprecedented extremes pose for the impact-based forecasting community. She posed the question of how to approach communities and talk about impacts that have never occurred in those locations. She noted that there is an opportunity to use some of the novel techniques employed in the climate world, including the use of storylines and scenarios to explore possible and plausible future conditions.

Considering the potential applications of impact-based forecasting in the security space, Coughlan de Perez concluded her remarks with a cautionary note about how pathways to impact may integrate assumptions that are not fully interrogated. She cited the war in Syria as a case where

TABLE 5-1 Typology of Compound Weather and Climate Events

| Compound Event Themes | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Preconditioned | An initial driver creates conditions that magnify impacts from a subsequent driver. | Heavy rainfall after a drought leads to greater flood damage. |

| Multivariate | A modulating factor creates multiple drivers and/or hazards leading to an impact. | La Niña conditions create concurrent droughts and heatwaves leading to agricultural losses. |

| Temporally compounding | A modulating factor creates a succession of hazards in a single place, leading to an impact. | Atmospheric conditions produce repeated heavy rainfall events leading to greater flood damage. |

| Spatially compounding | A modulating factor creates multiple, concurrent hazards in different regions, leading to a distributed, aggregated impact. | El Niño conditions lead to droughts in multiple places, leading to distributed crop failures. |

a dominant view of the climate–conflict connection involved a pathway between drought and conflict that may have crowded out some alternative pathways that might be better supported by evidence. As an example, she cited recent research suggesting that societal drought vulnerability and the Syrian climate–conflict nexus are better explained by agriculture than meteorology.

TOOLS FOR CLIMATE PREDICTIONS AND PROJECTIONS

In her remarks, Pegion described the tools used to develop predictions and projections within the weather and climate community. She noted that the weather and climate variability of concern for security questions exists on a continuum that extends from timescales of days and weeks to multi-decadal and centennial scales. In the shorter term, weekly and subseasonal events include floods and droughts, while seasonal timescales can include major shifts in temperature and rainfall. On interannual timescales, variability includes the well-known impacts of the El Niño and La Niña events. Beyond that, climate system variability on multi-decadal and centennial scales involves the longer-term trends in temperature, precipitation, and sea-level rise that are part of the IPCC’s discussions. Pegion noted that the research community is often stratified along these different timescales but emphasized that variability can be highly interrelated across scales. She noted that a seasonal prediction does not exclude climate impacts, since climate impacts can occur on seasonal timescales.

Pegion noted that a fundamental feature of climate predictions and projections is that their quality decreases as timescales increase. She led the audience through the series of projects within the weather and climate community, each of which grapples with this challenge within their particular range of concerns (Figure 5-2). She shared examples that the types of forecasting products produced in each range and discussed where predictive skill has been demonstrated and where it has not. Focusing on South Asia, she noted that multiyear predictive skill is not consistent across the region, and that it should be a key area for further exploration. Pegion concluded her remarks by evaluating the current data products from the various weather and climate projects. On subseasonal and seasonal timescales, the datasets are operational and able to be utilized in real time to make predictions.