Integrating the Human Sciences to Scale Societal Responses to Environmental Change: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 4 Best Practices Across Domains of Need from the Human Sciences

4

Best Practices Across Domains of Need from the Human Sciences

The panel was moderated by Planning Committee Member Stephen H. Linder, Professor of the Department of Management, Policy and Community Health in the School of Public Health at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston; Director of the Institute for Health Policy; and Co-Director, Community Engagement, Gulf Coast Center for Precision Environmental Research.

Panel members offered expertise on data access and use, behavior change and communication, and community engagement to mobilize environmental action. Shannon Dosemagen, Director of the Open Environmental Data Project and a Shuttleworth Foundation Fellow, shared insights on open data collection. Lynny Brown, Partner at Healthy Environments at Willamette Partnership, discussed the role of social-movements in addressing community needs. Steven C. Hayes, a Foundation Professor in the Behavior Analysis Program at the University of Nevada, shed light on behavior change and communication strategies. Ezra Markowitz, an Associate Professor of Environmental Decision Making at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, ended the first day of the workshop by providing critical perspectives on data access.

BUILDING ENVIRONMENTAL DATA COMMONS: THE ROLE OF DATA ACCESS, COLLECTION METHODS, AND APPROACHES DRAWN FROM THE HUMAN SCIENCES

Dosemagen presented the essential roles of data collection and data access, as well as the open science and practice tools used to support the work of communities affected by environmental injustices. She shared her experience working with the Public Lab,1 an organization that utilizes open tools for reliable community data collection. Additionally, Dosemagen works with the Open Environmental Data Project,2 which aims to “de-silo” environmental and climate data as tools to address environmental issues by bridging community knowledge using public data, software, and hardware. She noted that the Public Lab uses “open tools to work alongside communities and [collect] data that would support their organizing activities,” which may contribute to environmental policy and action.

___________________

1 Public Lab is a community-based nonprofit “democratizing science to address environmental issues that affect people.” More information about Public Lab is available at https://publiclab.org/

2 The Open Environmental Data Project pursues “opportunities based on their greatest impact for change, moving into overlooked and under-addressed spaces first and foremost. Our practices aim to create as much use as possible to people working at the cross-sections of these issues, whether it be in community, government, science, or other sectors of climate and environmental action.” More information about the Open Environmental Data Project is available at https://www.openenvironmentaldata.org/values-and-principles

Dosemagen began by highlighting the challenges associated with the use of data in environmental issue-related decision making. She emphasized the underlying scarcity of opportunities for integration of community-collected data into environmental decision-making processes and the need to increase such opportunities. She noted that accessing and utilizing open data drawn from government, academic, and/or research-related sources can be difficult. Dosemagen’s work builds on that of Elinor Ostrom and the concept of Governing the Commons,3 related to community-based governance of shared resources, as well as shared knowledge building and management, all of which are particularly relevant for marginalized communities. She emphasized that the idea of a “data commons” includes both data and resources, and serves as a strategic tool for community decision making and access to environmental governance. She argued that improved data management could make environmental knowledge more accessible, comprehensible, and usable for various stakeholders, including researchers, communities, government entities, journalists, and lawyers. Dosemagen stressed the need to break down barriers to give communities access to open data systems—and by so doing, empower them to bring about changes in environmental policy and action.

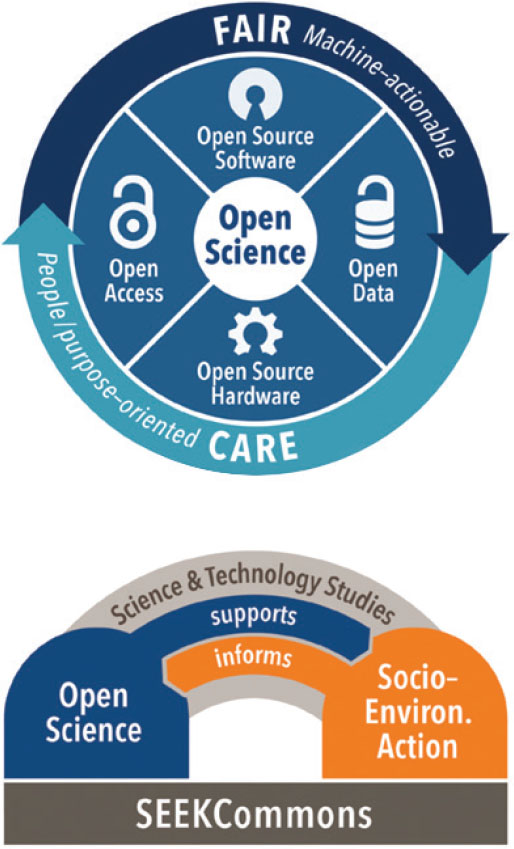

Dosemagen also presented two additional initiatives. The Beyond Compliance4 initiative, cofounded by Dosemagen and Gwen Ottinger of Drexel University, focuses on developing environmental data as a force for social change. The purpose of the initiative is to advocate for greater data sharing across public and private sectors, the goal being not only to unlock insights and engage a wide range of individuals and institutions but also to encourage environmental stewardship. The SEEKCommons (Socio-Environmental Knowledge Commons) project5 (Figure 4-1), a collaboration involving three partner entities—the University of Notre Dame, the University of Virginia, and the National Science Foundation—aims to create a network of various socio-environmental researchers and stakeholders to promote collaborations. The project’s goal has three parts: to work “alongside network members to provide concrete data problems and data sets that can be curated”; to establish an “environmental data commons”; and to facilitate meaningful, interdisciplinary work conducted among and involving social and environmental researchers, science and technology studies researchers, and open science practitioners. To promote open science and address environmental injustice, the project has also developed a data facilitators consortium, research hubs, and training programs for researchers, governments, and compliance officers.

To conclude her presentation, Dosemagen highlighted the importance of open data collection, data access, and data governance in the context of addressing environmental challenges and promoting social change.

MOBILIZING COMMUNITIES FOR ENVIRONMENTAL ACTION

Offering expertise in public health, collaborative leadership, and facilitation, Brown, a member of the Oregon Water Futures Collaborative (OWFC)6 and part of the Collaborative Coordination Team, focused her remarks on ways to successfully mobilize communities for “healthy living and environmental action.” The Collaborative Coordination Team includes members from Verde, the Coalition of Communities of Color, the Oregon Environmental Council, the University of Oregon, and the Willamette Partnership. Brown discussed how OWFC brings together diverse stakeholders, including water and environmental justice groups, Indigenous communities, academic institutions, rural organizations, and marginalized groups. It aims to shape the future of water management through capacity building and community-centered advocacy. To achieve this, OWFC disseminates and highlights uplifting stories of water justice and encourages leadership development through hosting workshops that can drive policy changes and enhance the effectiveness of community programs.

One of Brown’s key findings highlighted how front-line communities—for example, low-income; rural; native; Black, Indigenous, and people of color; and migrant communities—are already actively engaged in water-related

___________________

3 Ostrom, E. (2015). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316423936

4 More information on the Beyond Compliance project is available at https://www.openenvironmentaldata.org/pilot-type/beyond-compliance-network

5 More information on the SEEKCommons project is available at https://www.openenvironmentaldata.org/pilot-type/seekcommons

6 More information about the Oregon Water Futures Collaborative is available at https://www.oregonwaterfutures.org/#:~:text=The%20Oregon%20Water%20Futures%20Project,income%20communities%2C%20and%20academic%20institutions

SOURCE: Dosemagen, S. (2023). Building Environmental Data Commons: The Role of Data Access and Collection (slide #4), presentation for the Workshop on Integrating the Human Sciences to Scale Societal Responses to Environmental Change. Originally from https://github.com/SEEKCommons/seekcommons-art/tree/main/project-art. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 International.

environmental initiatives or have expressed the desire to be involved with OWFC. The OWFC team recognized that their contributions and insights gathered through storytelling, data collection, and information sharing were essential for reparative investments and legislative and policy decisions, as well as for empowering communities to address and adapt to environmental, water, and climate issues.

Brown highlighted a comprehensive OWFC report created for the State of Water Justice in Oregon.7 Though many people in Oregon struggle to access clean water, Brown suggested that front-line communities are significantly impacted by the water crisis, experiencing challenges associated with sprinklers, cooling systems, and air conditioning. She noted the report’s finding that communities of color, rural areas, and low-income populations bear the brunt of these water crisis-related challenges. Among the report’s most concerning statistics were those revealing the detection of lead in drinking water at 88 percent of Oregon’s public schools in 2016; the annual failure of 45,000 septic systems; and the disproportionate lack of complete plumbing in housing occupied by Black residents compared with housing occupied by White residents. Additionally, among the 50 largest U.S. metropolitan areas, Portland had the second-highest share of unplumbed households.

To address these disparities and elevate the priorities of underrepresented communities in the context of water policy decision making, the OWFC team emphasized the importance of building relationships and trust within underserved communities. Brown advocated for prioritizing community voices in the co-creation of outreach strategies that are flexible, adaptable, and accessible, and that make use of the existing values and language of the

___________________

7 Dalgaard, S. (2022). State of water justice in Oregon: A primer on how Oregon water infrastructure challenges affect frontline communities across the state. https://www.oregonwaterfutures.org/water-justice-report

SOURCE: Brown, L. (2023). Mobilizing Communities for Environmental Action (slide #11), presentation for the Workshop on Integrating the Human Sciences to Scale Societal Responses to Environmental Change. Originally from Brown, L., Dalgaard, S., Evans, T., Gastellum, J., Holliday, C., Medina, P., Poton, R., Reyes-Santos, A., Salcido, J., Sanchez, I., & Satterfield, V. (2022). Oregon water justice framework: Community driven principles and priorities to advance water justice. Oregon Water Futures Coordination Team. https://www.oregonwaterfutures.org/water-justice-framework. Reprinted with permission.

diverse range of participants. In 2021, OWFC advocated for and conducted community-engagement activities, such as online gatherings, phone interviews, and multilingual approaches, involving 104 participants including historically underrepresented populations and migrant communities. The goal was to identify statewide water crisis-related priorities, perpetuated by the compounding impacts of pressing issues such as COVID-19, wildfires, smoke, and flooding on community needs, mental health, economic survival, and an overall sense of safety. Through storytelling, the OWFC team sought to connect communities’ water-related values—such as spiritual elements, potability and hygiene, and bill payments—to influence reparative investments, inclusive legislative actions and policymaking, and community empowerment. Brown suggested that qualitative stories were used effectively during Oregon’s 2021 legislative session, resulting in a historic $530 million water package, including $1.5 million allocated explicitly for equitable water access and Indigenous energy resiliency.

Brown explained that, by working alongside community members and collecting feedback from tribal governments, researchers, state agencies, utilities, and environmental organizations, the OWFC team contributed to the development of the Oregon Water Justice Framework.8 This framework was motivated by community-based principles addressing the need to promote Indigenous water justice leadership, renter rights, water access and affordability, natural and built infrastructure for clean water, emergency preparedness, and community empowerment (see Figure 4-2).

There are so many different players, and they’re working separately and are siloed. But the lived experience of community members with water is not separated into silos; [community-driven principles] are integrated together, and experienced together, and overlap to inform one another.

___________________

8 Brown, L., Dalgaard, S., Evans, T., Gasteullum, J., Holliday, C., Medine, P., Poton, R., Reyes-Santos, A., Salcido, J., Sanchez, I., & Satterfield, V. (2022). Oregon water justice framework: Community-driven principles and priorities to advance water justice. Oregon Water Futures Coordination Team. https://www.oregonwaterfutures.org/water-justice-framework

The OWFC team realized that, in the realm of water and natural resource management, the experiences and expertise of communities must be integrated and overlapped, breaking down preexisting silos. Brown ended by pointing out that these collaborative approaches have generated actionable ideas and are leading the way to policy changes in the 2023 legislative session.

UTILIZING BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE TO DRIVE ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE AND ADDRESS ENVIRONMENTAL DISTRESS

Hayes began his presentation by recounting how, almost half a century ago, he co-authored the book Environmental Problems/Behavioral Solutions,9 which is still referenced today. He noted that using such dated literature is ultimately problematic and called for updated projects and research in the field. Hayes explained that early work in the discipline was dominated by “direct contingencies and feedback control,” yet the lack of government interest and funding limited investigation of other approaches. However, more resources have recently been allocated to behavior-change methods, with a greater emphasis on motivations. He highlighted newly developed tools, such as the website Tools of Change,10 that have been instrumental in promoting open access to social and behavioral change-related work.

Hayes emphasized the need for thoughtful and rapid innovations within social and behavioral sciences, reiterating his opinion that these disciplines should not remain fixated on 40-year-old publications. He called for new evaluations and analytic assumptions to bolster behavior-change data, as slow randomized trials alone cannot expedite academic advancement. Hayes highlighted the critical importance of enhanced training, programs, and procedures involving multiple stakeholders, not just limited to the physical sciences, to influence behavior change and produce knowledge.

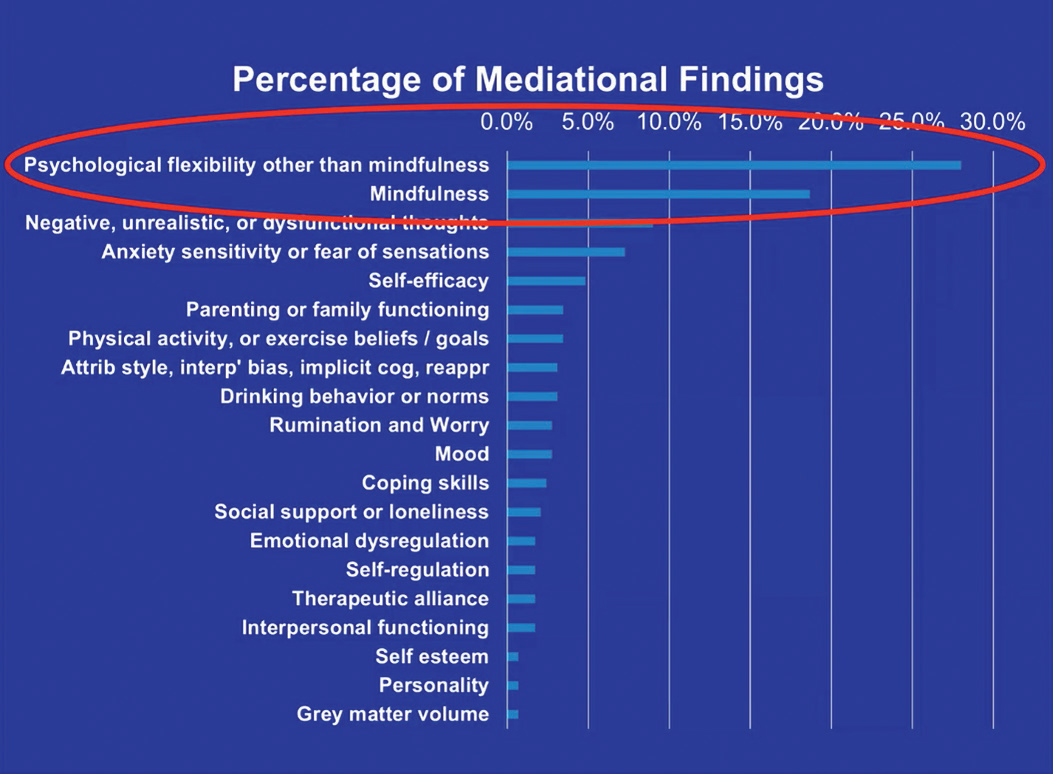

Hayes advocated an open science approach and emphasized the need to examine the “proximal indications of long-term change or mediators of change.” In the 2022 study “Evolving an Idionomic Approach to Processes of Change: Towards a Unified Personalized Science of Human Improvement,” Hayes and colleagues examined every randomized trial ever conducted on any psychosocial intervention related to mental health outcomes that claimed to have done a proper mediation analysis of why change happened. Their research identified 281 specific replicated findings out of almost 54,633 studies.11 Mediators of change were of various types, including affective, cognitive, attentional, self, motivational, physiological, behavioral, and sociocultural, and based on the understanding of how complex systems evolve and change, regarding variation, selection, retention, and context.

Hayes noted that psychological flexibility, including methods of mindfulness, acceptance, and commitment training, have emerged as crucial factors in developing behavior change. Figure 4-3 shows the percentage of psychological flexibility other than mindfulness compared to other mediational findings. He discussed the significance of three distinct considerations: openness to areas of change, overcoming emotional and cognitive barriers to change, and expanding connection to personal and community values. He also presented findings highlighting the following influential factors: psychological flexibility, mindfulness, anxiety sensitivity, self-compassion, rumination and worry, emotional rigidity, decentering, and behavioral activation.12

Looking toward the future, Hayes emphasized the critical role of evolutionary, behavioral, and cognitive sciences in promoting change, particularly in lower- and middle-income countries and the global south, or other countries with low levels of economic and industrial development. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), based on psychological flexibility, has been studied extensively, including in the context of lower-income and developing countries.13 The World Health Organization (WHO) has concluded that an ACT-based self-help

___________________

9 Cone, J. D., & Hayes, S. C. (1980). Environmental problems/behavioral solutions. Wadsworth, Inc.

10 More information about Tools of Change is available at https://toolsofchange.com/

11 Hayes, S. C., Ciarrochi, J., Hofmann, S. G., Chin, F., & Sahdra, B. (2022). Evolving an idionomic approach to processes of change: Towards a unified personalized science of human improvement. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 156, 104155.

12 Ibid.

13 Hayes, S. (2023). ACT randomized controlled trials (1986 to Present). Association for Contextual Behavioral Science. https://contextualscience.org/act_randomized_controlled_trials_1986_to_present

SOURCE: Hayes, S. C. (2023). Integrating the Human Sciences to Scale Societal Responses to Environmental Change (slide #12), presentation for the Workshop on Integrating the Human Sciences to Scale Societal Responses to Environmental Change. Originally from Hayes, S. C., Ciarrochi, J., Hofmann, S. G., Chin, F., & Sahdra, B. (2022). Evolving an idionomic approach to processes of change: Towards a unified personalized science of human improvement. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 156, 104155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2022.104155. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

approach called Self-Help Plus (SH+) can apply universally to any distress-creating circumstance.14 Hayes talked about how the WHO has developed ACT-based resources, such as cartoon books and audio sources, designed for stress management and coping with adversity. He discussed how, in the context of such crises as earthquakes, warfare, pandemics, and climate change, these stress-targeting resources have been informed by evidence and extensive field testing, including randomized trials with refugees in Uganda and Turkey.15

To foster compassion, empathy, and cooperation, Hayes emphasized the importance of shared commitments and values. Referencing Ostrom’s core design principles, he suggested the creation of an open science platform with “The Commons” qualities, which may assist in defining purposes for groups, informing decisions, monitoring agreements, integrating compliance options, and establishing conflict-resolution mechanisms. Hayes proposed revisiting early behavioral analytics ideas and focusing on the process-outcome link rather than relying solely on randomized trials. He advocated for testing processes and outcomes longitudinally within groups and measuring shared values and commitments, to better understand their impacts and their relationship with the change process. Hayes concluded that best practices might include employing a rapid iterative form of behavioral science, testing interventions focused on process-outcome linkages, and conducting longitudinal evaluations to build effective intervention packages.

___________________

14 More information on WHO findings is available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003927

15 Leku, M., Ndlovu, J., Bourey, C., Aldridge, L., Upadhaya, N., Tol, W., & Augustinavicius, J. (2022). SH+ 360: Novel model for scaling up a mental health and psychosocial support programme in humanitarian settings. BJPsych Open, 8(5), E147. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.533

MAKING THE NEXT WAVE OF ENVIRONMENTAL SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH MORE USEFUL ON THE GROUND

In the final presentation of the day, Markowitz shared his insights on constructive future development of environmental social science research. To integrate environmental social science on the ground, he emphasized the need for practicality, usability, and increased impact. Markowitz acknowledged that the topics he covered overlap with topics discussed by his colleagues in previous workshop discussions, and how his emphasis on mobilization is well-suited for the conclusion of day one. Markowitz highlighted several challenges that serve as barriers to positive change, including engagement efforts that fail to provide actionable and relevant insights that can be used by environmental actors and community-based organizations. He went on to point out the limitations of top-down approaches, which are often subject to power dynamics and overlook the need for self-determination and local ground-truthing or triangulation with empirical, directly observable evidence. Additional challenges Markowitz highlighted were undertheorized linkages and outcomes between communication, engagement, and behavior-change efforts. He emphasized that experimental research methods do not account for the “messiness” of interventions in the context of diverse populations. Additionally, he discussed the mismatched incentives among researchers and practitioners, organizations, or individuals, and the lack of consideration given to solutions’ scalability, feasibility, and cost.

Markowitz proposed several strategies that could address the previously mentioned challenges. First, he emphasized the importance of clear goals based on desired outcomes; in this context, he advocated for intentional, practice-driven outcomes bridging gaps between research and the “real world.” Second, he promoted designing interventions grounded in existing practices, suggesting guidance be given by experienced community organizations, socio-environmental movement actors, and relevant communication platforms. He emphasized the need to ground tools in realistic, scalable, cost-effective, ethical, and familiar approaches.

He went on to highlight the importance of involving practitioners and communities early and often throughout the research process. Markowitz discussed the value of deep and sustained engagement during campaign and message development, to promote trust and provide community stakeholders with valuable insights. He noted the importance of models that incorporate true collaboration and the multidirectional exchange of knowledge, expertise, experience, and ideas to solve vexing issues. He recognized diversity as a crucial aspect, calling for a tailored response to environmental issues and research to support communication and engagement efforts.

Markowitz underscored the value of triangulating insights through diverse research methods, stating that reduced reliance on single-method research designs may strengthen the robustness and generalizability of research findings and emphasize the need to establish and fund interdisciplinary teams. He pointed out that focusing on translating and providing access to research enhances the impact of existing work and influences future work; he called for researchers and institutions to ensure that their products are usable and broadly accessible.

In closing, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of complex environmental issues, Markowitz discouraged focusing solely on narrowly scoped research and stressed the critical importance of recognizing the overarching context and narratives into which research findings are synthesized—both within and across disciplines and domains.

PANEL DISCUSSION

During the panel discussion, Linder responded to a participant’s question about new kinds of evidence or data that should be addressed, and how to allow evidence the seriousness it deserves. Hayes emphasized the importance of examining the processes of change, and he advocated for idiographic approaches considering specific differences within groups and individuals over time.16 He mentioned the emergence of new statistical tools and machine learning techniques that can analyze high-density longitudinal measures. Additionally, Hayes focused on the need to ground research in the reality of the communities and individuals being studied, as well

___________________

16 For more information on idiographic approaches, see Hayes, S. C., Ciarrochi, J., Hofmann, S. G., Chin, F., & Sahdra, B. (2022). Evolving an idionomic approach to processes of change: Towards a unified personalized science of human improvement. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 156, 104155.

as the need to avoid vague and homogenizing language. Dosemagen highlighted the importance of considering the social, political, and cultural infrastructure alongside the technical aspects of data and evidence incorporation. She emphasized that the social context cannot be separated from scientific methodology and urged practitioners to be mindful of workplace behaviors that might hinder community members’ interactions with data. Markowitz underscored the importance of recognizing the nested nature of social systems and suggested pursuing multilevel modeling and data collection to better understand what factors matter for communities, individuals, or groups. The panelists also discussed the importance of trust, cooperation, and involvement in community-based work, urging decision makers to confer with communities and rely on their knowledge and leadership to build healthy communities and environments.

Linder raised a question from the audience about integrating new developments in the human sciences. Both Hayes and Markowitz emphasized the importance of a balanced approach that combines descriptive research and model development. Hayes argued for an open science approach that includes qualitative research and iterative processes to foster collaboration, with the intention of overcoming environmental and behavioral obstacles. He cautioned against simply throwing evolving technology-based solutions at problems without establishing a solid foundation. Markowitz agreed, highlighting the need for targeted research, individual-level interventions, and concrete decision making and modeling to understand broader implications. They both emphasized the value of interdisciplinary teams and community cooperation for effectively addressing complex environmental issues.