Integrating the Human Sciences to Scale Societal Responses to Environmental Change: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 6 Achieving Climate Action Through Community-Level Partnerships

6

Achieving Climate Action Through Community-Level Partnerships

On the second day of the workshop, the first panel was asked to provide perspectives on successful community-based initiatives and the role of such initiatives in addressing climate change mitigation and adaptation. Moderated by Linda Silka, Planning Committee Member and Senior Fellow at the Senator George J. Mitchell Center for Sustainability Solutions, University of Maine, the session featured three speakers who presented their expertise and experiences.

First, Abby Reyes, Director of Community Resilience Projects at the University of California, Irvine, shared examples of resilient communities. Second, Sara Constantino, Assistant Professor in the Psychology Department and the School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs at Northeastern University, explored the role of diverse relationships in fostering community capacity and resilience. Finally, Kristie Ebi, a Professor at the Center for Health and the Global Environment at the University of Washington, highlighted the crucial steps necessary to prioritize community well-being in the context of climate policies. Throughout the session, panelists addressed several areas: success factors, policy considerations, community readiness, messaging strategies for encouraging community involvement, and methods to evaluate cooperation.

COMMUNITY-ACADEMIC PARTNERSHIPS TO ADVANCE EQUITY-FOCUSED CLIMATE ACTION

Reyes opened the session by presenting a series of examples illustrating successful resilience-building at the community level. She started by emphasizing the importance of community-academic collaborations and the plethora of social-movement frameworks and methods that academics could draw upon to sharpen collective approaches to climate resilience. Next, she discussed a case study involving the U’wa Indigenous community in Colombia, who are in an ongoing legal battle to assert a framework for community-driven climate resilience and to stop companies from extracting fossil fuels from their ancestral lands. The case was taken to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which initially ruled in favor of the U’wa people, rejecting attempts to extract natural resources from their lands.1 However, over the past 25 years, Colombia has continued to allow extraction of fossil fuels, raising broad questions about legal consent, development, and Indigenous rights—claims now before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. Alongside legal teams pursuing legal action, Reyes stressed the need for longer-term approaches, including deep investment in Indigenous youth through education and development programs designed to train young people to become the next generation of climate-justice advocates.

___________________

1 More information about the U’wa Nation is available at https://justiciaparalanacionuwa.com/en/

Reyes emphasized that the focus of development be on accompaniment,2 building the capacities of community members rather than conducting theoretical research that may not be directly relevant to communities. Drawing upon a social-movement framework called “just transition,” Reyes explained that resilience is achieved when communities have the “means to protect and defend their cultural and biological resources even in the face of disruption.” Therefore, resilience requires eliminating inequities and adopting sustainable resource use. She argued that climate resilience is not merely about bouncing back but bouncing forward into new, equity-focused, sustainable systems for the future—systems that front-line communities are often best positioned to inform. She noted that University of California, Irvine faculty and staff have been engaging transdisciplinary expertise from social work, law, Chicano/Latino Studies, African-American Studies, and public health to practice accompaniment for climate resilience. Community-based opportunities have been co-created by working closely with community- and faculty-led research partnerships. These opportunities are informed by resilience approaches and include legal career opportunities focused on supporting just transition out of an extraction-based economy; codesigned, bilingual, worker-owned cooperative curricula; and the Community-Academic Partnerships to Advance Equity-Focused Climate Action (CAPECA), a 15-month training program in participatory, life-affirming research methods and partnerships.3 Reyes emphasized the value of promoting the direct participation of impacted communities by not only drawing on community-based training sessions but also distilling and empowering networks of minority-led climate-resilience planners. She noted that these peer-learning and referral networks are crucial to advocating for resilience work such as this example:

What Aura Tegria [Colombian Indigenous lawyer and youth leader] brought them [the young legal fellows] was the skills and stance of accompaniment. As a facilitator of social change in her own community, a role that has led now to her election as mayor, Aura practices accompaniment of the pueblo or community, and of her elders, the rivers, and the earth itself. It is a stance in recognition of what native Hawaiians might call kuleana, or a wanted obligation or responsibility. As a legal fellow at EarthRights International, Aura taught the non-Indigenous lawyers ways to deepen their practice of accompaniment. It’s a stance of humility and curiosity, of mutuality, [and of the] recognition that our futures are bound up together. It’s a stance of awareness that you don’t know all there is to know and that often you don’t know what you don’t know. It’s a stance of listening. It’s also a stance of critical analysis of one’s own positionality. These would be all sorts of power and privilege, a criticality that, when combined with our own alignment with community-defined aims, makes it imperative to harness one’s various privileges, to shift power and material resources from dominant institutions to climate-vulnerable communities.

The problem, according to Reyes, lies in the disconnect between institutions and the communities they are meant to serve. Equitable collaboration is critical to promoting community involvement and community-driven solutions and is accomplished by reallocating power to community members and fostering democratic participation. Strategic navigation of these programs and networks requires a solid, interdisciplinary team with specific roles focused on community-driven research, she stated. In this context, the 11 community-academic partnerships across the state of California trained by Reyes’s team each include local community researchers, facilitators, allied collaborations from academia, and community partners.

The statewide training emphasizes the importance of honoring existing expertise, building collective capacity, establishing partnerships, co-creating methods for action, uplifting community members’ voices, and embracing whole-systems thinking to break down disciplinary silos. She suggested that relevant training might focus on designing research using population education and participatory-action research practices. Her team’s trainings teach methods from the Coliberate approach to participatory-action research for community-driven climate-resilience planning. The Coliberate approach draws upon principles and tools from Theatre of the Oppressed,4 which can be used to identify a community’s analysis of root causes of inequities and to develop interventions to foster resilience. In a community-academic partnership, the trust that is built through such methods can open the door to strategic navigation and transformative approaches to climate planning.

___________________

2 Wilkinson and D’Angelo define accompaniment as the “intentional practice of presence, [which] emphasizes processes and relationships over outcomes, with the ultimate goal of leveraging privilege and collectively changing destructive systems.” Wilkinson, M. T., & D’Angelo, K. A. (2019). Community-based accompaniment & social work—A complementary approach to social action. Journal of Community Practice, 27(2), 151–167.

3 More information on CAPECA is available at https://sites.google.com/facilitatingpower.com/capeca/home

4 More information about the Coliberate process is available at http://www.collabchange.org/coliberate

In conclusion, Reyes discussed where academics might turn for social-movement frameworks and popular education methods when designing research to enable a resilient civic body. She offered that scaling a pilot program like CAPECA requires careful consideration and planning. Reyes argued that climate-vulnerable communities cannot afford to wait for action, and they are not waiting; society is currently in a state of collective acceleration. Thus, Reyes supports the many academics and community members already utilizing these methods and disciplines and urges participants to learn from these experiences. Accompaniment as both a skill and a stance, she finds, is learned through building relationships, or what in popular education might be called “making the road by walking.” She asserted that, for relevant climate solutions, the locus of knowledge production has shifted away from traditional campus settings, indicating a broad shift in power dynamics that includes the imperative to redistribute material resources from academia to front-line communities through equity-focused community-academic partnerships. In closing, Reyes highlighted the complexities and nuances of implementing community-driven climate resilience and the importance of ongoing exploration and collaboration.

COLLECTIVE ACTION FROM THEORY TO PRACTICE

Constantino delved into the role of relationships in fostering community capacity and resilience. She emphasized the importance of collective action and transformative change across various actors, systems, and scales to address climate change mitigation and adaptation. Furthermore, she stressed the importance of bottom-up social change, particularly in the context of government inaction, and her remarks explored the drivers of collective action, information- and service-distribution efforts, and the facilitators of transformational change. She discussed the embeddedness of individuals within their social networks and groups, which impacts relationships, behaviors, physical and institutional networks, norms, feedback, and peer influences.

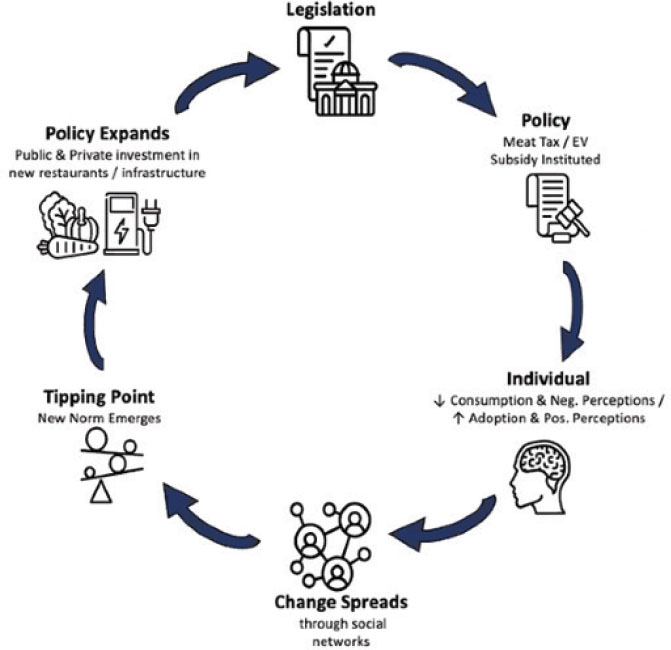

To illustrate the dynamics of social tipping points (Figure 6-1), Constantino used the example of electric vehicle adoption, in which changes in people’s values spread through social networks, leading to broad-based adoption and market response. However, successfully implementing such changes requires community buy-in, and local

SOURCE: Constantino, S. (2023). Collective Action from Theory to Practice (slide #6), presentation for the Workshop on Integrating the Human Sciences to Scale Societal Responses to Environmental Change. Originally from Weber, E. U., Constantino, S. M., & Schlüter, M. (2023). Embedding cognition: Judgment and choice in an interdependent and dynamic world. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 32(4). 328–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214231159282. Reprinted with permission from Sage.

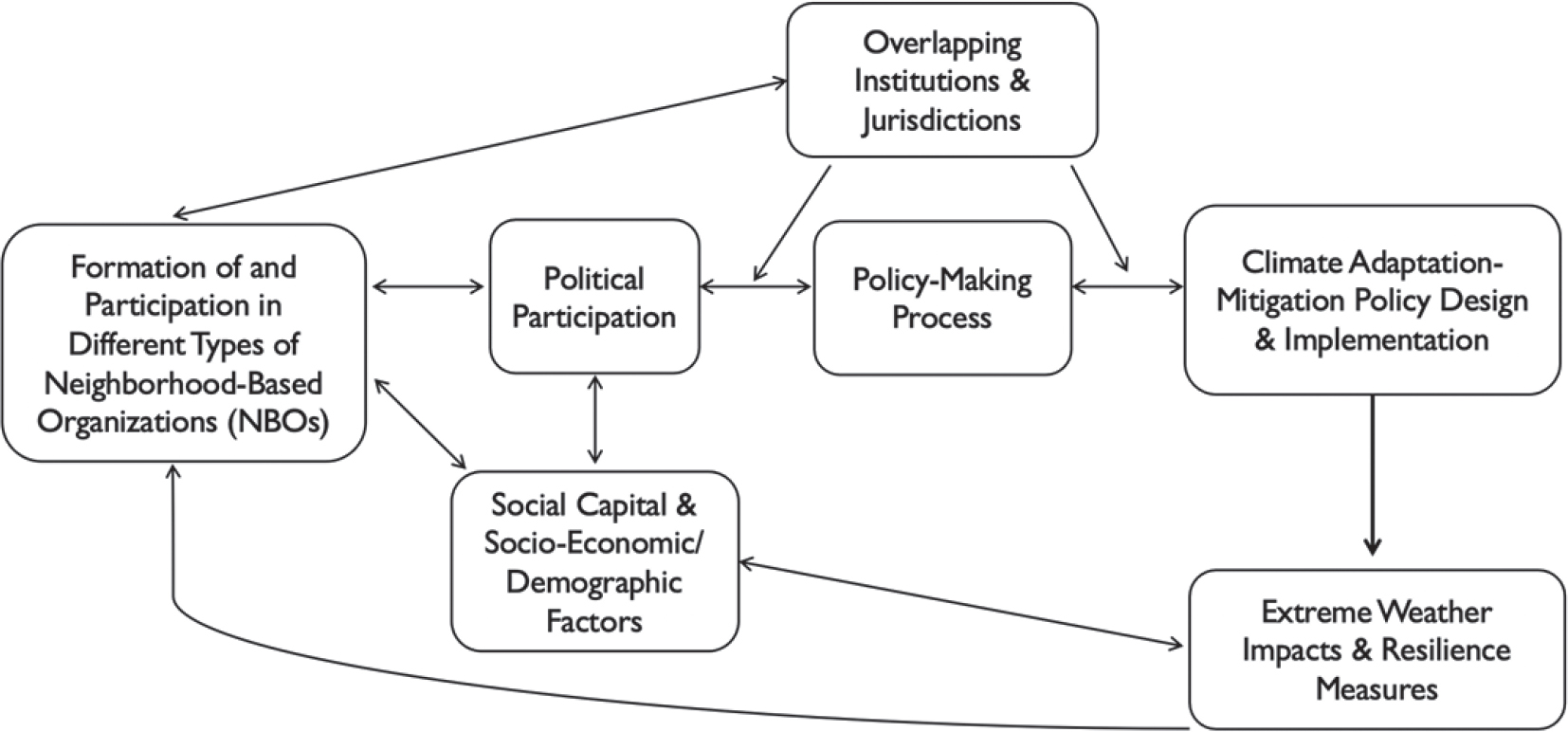

SOURCE: Constantino, S. (2023). Collective Action from Theory to Practice (slide #14), presentation for the Workshop on Integrating the Human Sciences to Scale Societal Responses to Environmental Change. Originally from Constantino, S., Cooperman, A., & Muñoz, M. (2023, July 1). Neighborhood-based organizations as political actors: Implications for political participation, inequality, and climate resilience. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4496935 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4496935. Reprinted with permission.

opposition can create barriers and distributional challenges. She highlighted ongoing case studies in the Texas Gulf Coast and Miami, Florida, pointing out the relationship between community engagement and resilience in the face of climate risks. In particular, she emphasized the importance of neighborhood-based organizations (NBOs) in shaping policy outcomes and building community resilience.

Constantino raised critical questions about the drivers of public participation in policy and collective action, what researchers can offer communities, and how historical factors shape these dynamics. She noted that coastal communities face varying levels of risk and exposure to sea-level rise, and adaptation efforts and provision of public services can be hyperlocal and influenced by neighborhood-level organizations, including homeowner associations and less-formalized associations.

Constantino emphasized that her research reflects the importance of building community partnerships. She described her two-year involvement on a National Science Foundation project that involved trust building through initial scoping visits, refining collective research questions, and developing reciprocal engagement methods. Key stakeholders and public comments were used to select interviewees, which helped bridge community access and identify key issues for specific communities. Her research methods include surveys, in-depth interviews, experiments, and analysis of meeting agendas. The team will conduct focus groups in the fall.

Constantino highlighted the significance of NBOs in shaping local responses to climate impacts (Figure 6-2). As an example of one type of NBO, she discussed the historical growth of property owner associations (e.g., homeowner associations and condo boards), which outnumber local governments and vary by both incentives for incorporation and service provisions. Constantino also mentioned voluntary associations, which include neighborhood and community associations and civic leagues.

Using a large, nationally representative online survey, Constantino found that participation in NBOs is correlated with both receipt of government relief and support after extreme weather events and increased preparedness for future weather events. Participation is predicted by higher levels of social capital. She also noted that residents affiliated with some NBOs, including religious organizations and homeowner associations, were more likely to prefer government decentralization and have conservative values.

Constantino suggested that research benefits of community-engaged behavioral sciences include enriching and improving theories and evidence of social change in complex institutional settings, creating new data sources through participatory action research, and refining research on context-specific knowledge. In addition, she highlighted the value of community-engaged behavioral sciences and discussed some of their challenges,5 including generalizability, funding mismatches, lack of academic incentives, and community and academic resistance. Finally, she emphasized that the path forward would involve three areas: prioritizing community-based research through funding and institutional support, providing opportunities for learning and development, and promoting collaboration between researchers and stakeholders to implement surveys tailored to community priorities.

ESSENTIAL STEPS TO ENSURE THE WELL-BEING OF COMMUNITIES IS FRONT AND CENTER IN CLIMATE POLICIES

Ebi, the third panelist, emphasized the crucial steps required to prioritize the well-being of communities when setting up climate policies, and she highlighted the importance of framing climate change as a health issue. Ebi noted that people care deeply about their health and their communities. However, there are challenges when integrating health considerations into climate policies. She explained that climate change has traditionally been framed as an environmental issue. Still, there is a growing recognition of the importance of risk-based approaches and climate-resilient development pathways.

Ebi discussed that, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), climate change risks are multidimensional.6 These risks include hazards associated with the changing climate, exposure to those hazards in various local contexts, and the vulnerability of specific populations and places over time. In addition, climate change affects health both directly and indirectly, with resulting impacts ranging from vector-borne diseases to

___________________

5 Caggiano, H., & Weber, E. U. (2023). Advances in qualitative methods in environmental research. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 48.

6 More information about the IPCC is available at https://www.ipcc.ch/

malnutrition. Therefore, Ebi stated, managing these complex challenges requires strengthening the capacity of health systems to respond to climate-related health risks.

To ensure active engagement of the health sector in climate action, Ebi emphasized the importance of collaboration and communication. She argued that stronger collaborations need to be established between the health sector and those involved in climate change mitigation and adaptation. Two-way partnerships can ensure the integration of health information into decision-making processes and permit health systems to receive the necessary support and investment. Ebi went on to highlight the value of increasing health-related climate research and funding for such initiatives. She noted a mismatch in that, where international climate adaptation funds are available, less than 1 percent of these funds are allocated to health. She said the health sector requires more resources to address the challenges and vulnerabilities caused by climate change.

Considering local climate-action opportunities, Ebi discussed the potential co-benefits of mitigation efforts for health. For instance, reducing exposure to air pollution from coal-fired power plants mitigates climate change, improves air quality, and reduces the incidence of respiratory diseases such as asthma. By quantifying the health benefits of mitigation, it becomes evident that acting at any governance level can have immediate positive impacts on health outcomes and healthcare costs.

Ebi stressed the importance of community engagement in and support of climate action because communities ought to actively identify their concerns and work collaboratively with others to co-produce sustainable solutions. At the international scale, sustainable-development pathways7 have been proposed that provide contextual information for local communities to inform decision making and action.

In conclusion, Ebi emphasized not only embracing transformative approaches but also acknowledging that progress toward a sustainable future is underway. She called for creative approaches to expanding climate action-related pathways, ensuring long-term trends are considered and communicated effectively. Ebi concluded that, by prioritizing health and community engagement, climate policies can better serve the well-being and resilience of communities.

PANEL DISCUSSION

During the discussion session, several important topics were addressed through the following questions. A question from the audience generated a discussion about timing and temporal scale-related challenges in the context of community engagement. Panelists highlighted how producers of guidance documents can affect the flexibility of early stages of the community-engagement process. Ebi mentioned that the timing of engagement efforts is context-specific and influenced by historical evidence. Referring to the Pacific and Asia regions where existing plans drive the timing of adaptation and mitigation, she mentioned unexpected challenges that may arise, such as those posed by COVID-19. Constantino said that an unexpected benefit of the COVID-19 pandemic involved the extension of project timelines, allowing for deeper engagement and more meaningful relationships. Reyes added that radical connection with communities takes time and develops through inquiry, planning, action, and reflection. Panelists emphasized that listening to communities and understanding their needs is crucial when determining the appropriate timing for and provision of required assistance.

A question was raised about how to begin, facilitate, and complete projects collaboratively. Constantino commented that, in her experience, sharing materials with stakeholders and partners has helped to refine their survey instruments and adjust project goals to align with community input. She emphasized the importance of adapting questions and materials to be culturally appropriate for specific locations and contexts. Silka mentioned the importance of introducing new faculty to community groups and building trust by facilitating introductory interactions between institutions and community members. Reyes shared an example drawn from the process of U’Wa youth development, in which funding allocation was required to support community-based research centers and staff. She mentioned that long-term goals are measured through metrics related to desired outcomes, such as accessing housing, accessing healthcare, and addressing socio-economic issues.

___________________

7 The five ICLEI Local Governments for Sustainability pathways are the low emission development pathway, the nature-based development pathway, the equitable and people-centered development pathway, the resilient development pathway, and the circular development pathway. More information about the ICLEI is available at https://iclei.org/our_approach/