Barriers, Challenges, and Supports for Family Caregivers in Science, Engineering, and Medicine: Proceedings of Two Symposia (2023)

Chapter: 2 Outlining the Challenges Facing Caregivers in STEMM

2

Outlining the Challenges Facing Caregivers in STEMM

Christina Mangurian, M.D., M.A.S. (University of California, San Francisco [UCSF]) opened the first symposium with an overview entitled “Promoting Equity for Caregivers in STEMM [Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics, and Medicine].” That is because, she said, supporting family caregivers is a pragmatic way to achieve gender equity in the sciences. “The system was not built with women or family caregivers in mind, so it is important to think about the policies and procedures that impact this population,” she stated. Committee member Reshma Jagsi, M.D. (Emory University) introduced Dr. Mangurian and facilitated the discussion that followed.

FRAMING THE PROBLEM

In summarizing her research on caregivers, Dr. Mangurian issued several caveats. First, much of the data focuses on women, although women are not the only ones affected by caregiving responsibilities and gender is not binary. She also noted that there are insufficient data regarding women of color, although she echoed Elena Fuentes-Afflick’s, M.D., M.P.H. (University of California, San Francisco) introductory remarks that caregiving disproportionately affects women of color in STEMM (see Chapter 1). Dr. Mangurian’s research focuses on women in medicine, although there are similarities across the sciences. She acknowledged partnerships and

collaborations that “shine a spotlight on problems in an effort to build rocks for policymakers to throw to promote gender equity.”

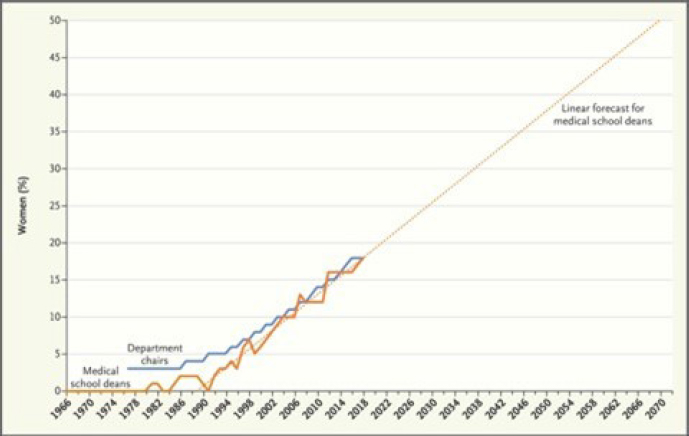

As discussed in a 2020 report issued by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM, 2020), the participation of women in STEMM declines along the educational and career pathway. The highest proportion of women is at the bachelor’s degree level, and the proportion falls as faculty reach professor ranks. “Women do not advance not because they lack talent and aspirations, but because they face multiple barriers, including implicit and explicit bias, sexual harassment, unequal access to funding and resources, and higher teaching and mentorship loads,” Dr. Mangurian stated. In 2015, the British Medical Journal published a cross-sectional study of more than 1,000 chairs in 50 top medical schools and found that there were more men with moustaches, 19 percent of department chairs, than there were women, who represented 13 percent of chairs in the top 50 medical schools (Wehner et al., 2015). While the article presented the information somewhat lightheartedly, Dr. Mangurian commented that the comparison highlights a problem. In collaboration with colleagues, Dr. Mangurian projected that gender parity will not be achieved in U.S. academic medical leadership for 50 years based on the current trajectory (see Figure 2-1; Beeler et al., 2019).

Caregiving responsibilities are one of the barriers obstructing gender equity, because women are more likely to be caregivers and bear the burden of domestic responsibilities, Dr. Mangurian said, a reality referred to as the “maternal wall” (Williams and Dempsey, 2014). This wall prevents mothers from progressing in many different fields, including medicine, as mothers are seen as less competent and effective as leaders. Dr. Mangurian pointed to a recommendation of the National Academies 2020 report that leaders “adapt actionable, evidence-based strategies and practices . . . that directly address particular gender gaps in recruitment, retention, and advancement of women in science, engineering, and medicine within their institution” (NASEM, 2020). She stressed the role of institutional policies to create structural changes, rather than waiting for the broader culture to change.

FAMILY LEAVE POLICY RESEARCH

Dr. Mangurian and colleagues surveyed the top 10 medical schools in the United States to learn about their family leave policies for faculty, residents, and staff. For faculty, 100 percent of the institutions had a policy, and provided 8.6 weeks of paid leave on average. For residents, 50 percent had

SOURCE: Christina Mangurian, Workshop Presentation, February 27, 2023, from Beeler et al., 2019.

a policy, providing 5.7 weeks of leave on average. For staff, 17 percent had policies, offering an average of 6 weeks of paid leave (Riano et al., 2018). This differential brings up privilege issues for faculty versus residents and staff, but even the faculty leave does not adhere to recommendations from pediatricians, who recommend 12 weeks of family leave, she commented.

Another study focused on leave for medical school students (Roselin et al., 2022). It found that only 14 percent of schools had substantive, standalone parental leave policies for students. Most offer a leave of absence, but not specifically for parents. Extended periods of leave during training affects long-term earnings and has other effects, the authors note. The recommendations for medical schools offered in their work include to adopt a formal and public parental policy, provide an academic adjustment option for enrolled parents, guarantee approval to take and return from leave, and continue students’ health-care and financial benefits during the leave. She added that the lawyers involved in this research suggested the deficit of robust parental leave policies for students may violate antidiscrimination laws.

Along with outlining potential legal requirements, Dr. Mangurian discussed the mental and physical health effects of family leave. A literature

review across fields (Van Niel et al., 2020) showed multiple benefits of paid family leave: (1) decrease in postpartum depression and intimate partner violence; (2) improvement in infant attachment and child development; (3) decrease in infant mortality and rehospitalizations; (4) increase in pediatric visit attendance and timely immunizations; and (5) increase in breastfeeding initiation and duration. “It’s a no-brainer,” Dr. Mangurian said. “In medicine, we should be leading the effort for 12 weeks of paid family leave.”

After decades of work by many individuals, UCSF moved to 12 weeks of paid family leave, she reported. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and American Board of Medical Specialties have approved at least 6 weeks of paid leave for residents and fellows, which she said was a move in the right direction.1

INPUT FROM INFORMAL CAREGIVERS

Dr. Mangurian strongly supports paid leave for faculty to care for other family members besides newborns. In the midst of receiving her first National Institutes of Health career development award, Dr. Mangurian said her son became ill and required extensive hospitalization and isolation for 2 years. She noted her good fortune in having financial, family, and other support, but many people do not. The experience shaped her career and research interests beyond academic medicine itself, including being selected to lead the Doris Duke Fund to Retain Clinical Scientists program at UCSF.2

To understand the prevalence of informal caregiving, Dr. Mangurian and colleagues polled members of the online Physician Moms Group (https://mypmg.com). Sixteen percent said they are informal caregivers, and some identified as “triple caregivers”: caring for patients, children, and ill family members. They have significantly higher rates of burnout and anxiety, compared with other physician mothers, yet few policies allow paid family leave across a woman’s lifespan (Yank et al., 2019). At the start of the

___________________

1 For more information on the policies, see https://www.acgme.org/newsroom/blog/2022/acgme-answers-resident-leave-policies/ and https://www.abms.org/policies/parental-leave/.

2 The Doris Duke Fund to Retain Clinical Scientists was launched in 2015 to help sustain research productivity of physician scientists when faced with periods of family caregiving responsibilities and to raise awareness about the importance of added research assistance for caregivers as a retention mechanism. For more information, see https://www.dorisduke.org/funding-areas/medical-research/fund-to-retain-clinical-scientists/.

UCSF Faculty Family-Friendly Initiative, a cross-sectional, mixed-methods survey of faculty found 11 percent of respondents were informal caregivers (rising to 15.5 percent among school of medicine faculty with children).3 Caregivers in the survey suggested policies such as expanded family leave, increased flexibility, and financial support would be most beneficial to them.

Dr. Mangurian noted her own bias while conducting this work in assuming that the greatest challenges for caregivers happened when they were caring for young children. Her perspective shifted as she entered the phase of the sandwich generation and her dad was recently diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. In fact, the weekend before the symposium, her father broke his hip and was hospitalized, leading her to almost cancel the presentation. While noting that her father was doing okay, she pointed out that caregiving affects faculty across their lifespan, not just at the period where they are caring for young children.

Dr. Mangurian highlighted early evidence of the impact of COVID-19 on caregivers. Among the groups most vulnerable for psychological sequelae during the pandemic were women and caregivers. A National Academies committee on the impact of COVID-19 on the careers of women in academic science, engineering, and medicine conducted a national survey of 933 women in STEM (NASEM, 2020). Almost three-quarters said the pandemic had a negative effect on their work, with both increased workload and decreased productivity. Many reported they put the well-being of their family ahead of their own, and Dr. Mangurian observed that the mental health implications and other consequences from this will last a long time.

She was part of a team to conduct a study on physician mothers that took place early in the pandemic, with recruitment in April 2020. Greater than 40 percent of participants had symptoms consistent with anxiety, compared with 19 percent of the adult population before COVID-19. Those most at risk were frontline workers and informal caregivers (Linos et al., 2021; Halley et al., 2021), which she believes is an underreporting.

CONCLUSIONS

Dr. Mangurian offered her recommendations to support caregiving academic scientists. First, she urged the institution of family-friendly policies, including 12 weeks of fully paid childbearing leave (or equivalent

___________________

3 For information on the UCSF Faculty Family-Friendly Initiative, see https://facultyacademicaffairs.ucsf.edu/faculty-life/3FI.

policies for students); lactation rooms and protected time for breast milk pumping; onsite childcare services with emergency backup care; paid catastrophic leave and/or sick leave for informal caregivers beyond the minimum levels of the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA; P.L. 103-3); and career flexibility.

Dr. Mangurian also called for improved mentorships, sponsorships, and targeted funding for family caregivers. She urged centering efforts on women of color, which would have benefits for all women. Examples include research support for family caregivers, such as the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation’s Fund to Retain Clinical Scientists, and peer mentorships, such as WARM Hearts.4 Peer mentoring is not only helpful, she commented, but also does not add to the burden of institutions or more senior women. She also urged sponsorships to target women to create more equity in STEMM.

Recapping her presentation, Dr. Mangurian concluded that

- gender disparities in academic medicine leadership persist and are not projected to close for another 50 years at the current rate of change;

- current family leave policies in medicine are limited, which affects the physical and mental health of caregivers;

- unpaid caregivers experience psychological distress, which has been heightened during the COVID-19 pandemic; and

- institutions should develop stronger family-friendly policies across the lifespan of faculty members.

DISCUSSION

To launch the discussion, Dr. Jagsi asked Dr. Mangurian to reflect on ways that academic medicine has stigmatized caregiving and any way to transform that culture. To illustrate the stigma with a personal example, Dr. Mangurian shared that when she was first appointed vice dean at her institution, her father had been facing health challenges. She had pondered whether to talk about her father’s health situation and she was advised not to. “This speaks to how we are supposed to put up a front, especially in medicine,” she said. She has tried to be open about her caregiving responsibilities intentionally so that others see she could advance her career, “but we are not

___________________

4 For information on WARM Hearts, see https://zsfg.ucsf.edu/warm-hearts.

there yet.” She also noted a further stigma around mental health, in which it is viewed as more “acceptable” to say family members are struggling with a physical illness than a mental illness. She noted the peer groups that are part of the Doris Duke program are helping transform culture by empowering participants to be able to speak about their own challenges. It is meaningful to institutions to receive recommendations from a group of outstanding faculty researchers, rather than individuals, she said.

Committee member Mary Blair-Loy, Ph.D. (University of California, San Diego) commented about the need to reduce stigma through universal policies that cover maternal and paternal leave, as well as leave for adoptions and fostering. Dr. Mangurian strongly agreed with the value of paid family leave for all who are welcoming a child in their home. She noted most of the data is on paid maternity leave, but that investing in paid leave for caregivers of all genders is worthwhile. Dr. Jagsi commented that a gendered effect of only providing paid leave to a mother is that she is perceived as the “expert parent” throughout the child’s life.

Committee member Ellen Ernst Kossek, Ph.D. (Purdue University) highlighted her research with economics faculty that showed that paid leave decreased women’s chances to attain tenure. She also urged more flexibility, such as a reduced workload rather than stepping out of the workforce entirely. Dr. Mangurian underscored the challenges to change workforce policies within the prevailing culture. For example, data show that when some men take family leave, they use the leave to write more grant proposals and publications. She said increasing the number of women in middle and top leadership positions could create change, as well as thinking across the life span. If workloads are reduced, the reduction must be meaningful, she added. Dr. Jagsi commented on the “soft pressure” at some institutions for men not to take leave or to emerge after leave with a book or other product. She urged creative approaches to account for variations of lived experience, and added that STEMM professions can lead the way, noting the transformative effect of the National Academies report on sexual harassment (NASEM, 2018).

Speaking from a business perspective, committee member Marianne Bertrand, Ph.D. (University of Chicago) shared a concern about the negative effect of leave policies on women’s careers. She noted the potential trade-off in which these policies may retain women but also hamper their career advancement. In the consulting world, one such result is that women are not allocated to the most interesting clients because of the concern they will take time off. Dr. Mangurian said this problem applies in medicine,

too, such as when women are not considered for sponsorship and other opportunities. Yet, she countered, these life experiences are beneficial for individuals to grow, empathize better with team members and patients, and strengthen their value to an organization. The men at the table also need to talk about the importance of caregiving, she said. The next generation entering the field is more willing to challenge the status quo, she added, but leaders need to act now.

A policy that gives everyone time off after the birth of a child can have unintended consequences when men are under pressure to show they are “ideal workers” and women face pressure to show they are “ideal mothers,” posited committee member Joan Williams, M.A., J.D. (University of California, San Francisco). In contrast, she noted that Harvard Law School changed its family leave policy so that those on leave must certify that they spend at least 50 percent of their time on caregiving. “That begins to change the norms within the institution, so the policy is associated with responsible parents who are doing right by their children,” Ms. Williams said. Well-designed policies must consider social norms, she stressed. Regarding the potential negative effect on leave policies, she observed that some mothers will continue without leave, but others will drop out entirely. “It’s a numbers game,” she said. “If the mothers take leave and their careers are dinged, that is unacceptable. But it is better than if they drop out, which would be the likely outcome.”

Dr. Mangurian added that privilege and family wealth play a role. Hiring a paid caregiver allows for more flexibility but is expensive. Diversifying the STEMM workforce means providing financial support, ensuring the continuation of health insurance, and other issues. In considering the tradeoff between expanding leave policies and slowing down women’s progress, Dr. Mangurian said this needs to be measured. She suggested pilots can be developed and tweaked as needed. There may be ways to provide funding for “helping hands,” such as for a research assistant or grant writer. Beyond leave policies, there is often broader pressure not to take time off, observed committee member Robert Phillips, Jr., M.D. (American Board of Family Medicine), bringing up that Americans do not take all the paid vacation leave they are due. In addition to a focus on policies, he suggested looking at the field of behavioral economics to create “culture nudges” that taking leave is not only acceptable but also rewarded. These incentives might include addenda in grants or some kind of mitigation to recognize that team members take breaks. Rather than just tacit support, he suggested that sponsors acknowledge and formally support these “nudges” in their applications. Dr.

Mangurian agreed with a reframing, which could include an accountability metric in which leaders are evaluated on whether their faculty took vacation time. Psychiatrists and health economists have found that when workers do not take breaks, they are not as strong.

A question from an attendee homed in on the situation for staff, who hold less privilege than faculty across institutions, as well as for faculty and others at underresourced institutions. Dr. Mangurian concurred that this issue needs more attention. Institutions can learn from one another, she noted, in developing and using funding mechanisms. She suggested the committee consider how to finance supportive policies and how the information can be readily accessible to all institutions. Faculty who run research labs have an additional pressure when taking leave, and a participant asked how to address this pressure in the context of caregiving. Dr. Mangurian suggested building in more redundancy, such as to assign a junior faculty member, senior postdoc, or senior colleague, with dollars set aside to do these tasks so the labs can continue to function.

Terminology came up to conclude the session. “Informal” may undermine the important role that people are undertaking, a participant suggested. The term is an issue, Dr. Mangurian agreed, although it is what is used in the literature to differentiate from paid caregivers (e.g., home health aides). She commented that the committee has broadened the term to “family caregivers,” but it is still stigmatized. She concluded with the emphasis on caregiving across the life span and across various points of challenges.

This page intentionally left blank.