Barriers, Challenges, and Supports for Family Caregivers in Science, Engineering, and Medicine: Proceedings of Two Symposia (2023)

Chapter: 4 Organizational Policies Supporting Caregivers in STEMM

4

Organizational Policies Supporting Caregivers in STEMM

Committee member Hannah Valantine, M.D., M.B.B.S. (Stanford University) moderated a session on organizational policies supporting caregivers in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine (STEMM). Debra Lerner, Ph.D. (Tufts University) summarized her research on academic medical centers as employers. Kate Miller, Ph.D. (University of Pennsylvania) provided a broader workplace context, with specific reference to her research on U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) caregiver programs.

ACADEMIC MEDICINE AS AN EMPLOYER

Drawing from research conducted with the Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregivers (Lerner, 2022), Dr. Lerner began by providing a baseline for what is known about caregiver employees, defined as “those providing mainly unpaid help to a family member needing assistance due to an illness, disability, and/or aging.”1 Through a secondary analysis of the highest-quality data available, she said that an estimated 18 to 22 percent of the U.S. labor force take on this role, often transitioning in and out of caregiving roles. Most are employed full-time; thus, she referred to their unpaid caregiving responsibilities as “invisible overtime.” They are represented in all occupational,

___________________

1 For more information on the Rosalynn Carter Institute, see https://www.rosalynncarter.org/.

earnings/socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic groups. Caregiving services take an average 20 hours per week, with more hours in co-residing situations. The data show that caregivers find the work rewarding, but it is still a strain emotionally, physically, and financially. Although normative in terms of the numbers affected, she pointed out that caregiving is still stigmatized and treated as unusual. Moreover, work/family policies and programs do not always fit caregivers’ specific needs.

Multiple sources of friction occur between caregiving roles and employment, Dr. Lerner reported. About 60 percent of caregiver employees reported that work, careers, and productivity have been disrupted by caregiving, and about one-third have voluntarily left a position because of their caregiving responsibilities. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) has seen an increase in the volume of family responsibility discrimination cases in the past 10 years, and caregiving discrimination was the second most common category of claim. A national survey that she and colleagues conducted called the Caregiver Work Limitations Questionnaire (Lerner et al., 2020) found two kinds of functional influences on productivity: presenteeism and absenteeism. The average productivity loss due to presenteeism (having difficulty functioning at work, although showing up) per caregiving employee was 11 percent, and the average annualized at-work productivity cost per employee was $5,281, assuming an hourly wage of $25. In terms of absenteeism, caregivers reported they missed an average of 3.2 workdays in the prior month, with an estimated average productivity loss of 2.2 percent or $1,123 per caregiving employee.

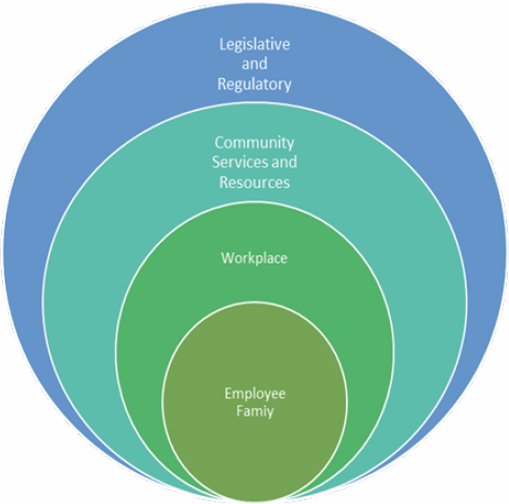

Dr. Lerner noted that academic medicine, like all workplaces, is a domain within a larger, interdependent ecosystem (see Figure 4-1). “We know that we have a community service system in disarray,” she commented. “That creates all kinds of problems not only for individual employees and their families, but also for workplaces to put interventions into effect that will help their caregivers.”

Academic medicine is in a unique place to find innovative solutions to support family caregivers, Dr. Lerner posited, and this innovation should be part of the academic medicine mission. The medical care system relies on unpaid family caregivers to complement the medical services that patients receive, so the importance of this role is well recognized. She suggested three directions for academic medicine: (1) lead by example as an employer that is committed to improve the quality of working life of employees and trainees, (2) engage and integrate family caregivers into patient care, and (3) leverage their unique position of power and influence to promote broader system and policy change.

SOURCE: Debra Lerner, Workshop Presentation, February 27, 2023.

The research on interventions to support caregiving employees is spotty and characterized by different research questions, populations, and outcomes, Dr. Lerner said. Nonetheless, the evidence identifies five intervention types as promising for academic medicine and all employers to different degrees: (1) flexible work arrangements, (2) caregiver-friendly workplaces, (3) psychotherapy/counseling, (4) connection to formal services/care, and (5) engaging caregivers in decision-making about the care recipient’s case and support.

Elaborating on these interventions, Dr. Lerner said flexible work arrangements are the most frequent strategy used by caregivers, either reducing their hours or changing their schedules. Results examining flexible arrangements suggest that caregivers utilizing these tend to be better at maintaining employment, though the research has not specifically examined potential differences between academic employment and other types, if there are any. She noted sparse research on outcomes of hybrid or remote work, although she is conducting a trial on this now. In studies of alternative arrangements, most caregivers prefer reduced hours versus compressed schedules or job sharing because the later arrangements tend to compress

demand into a shorter amount of time, rather than reducing demand. Dr. Lerner noted, however, that this creates a problem because part-time work or other ways of reducing hours risks lowering earnings and benefits.

As Dr. Lerner described it, a caregiver-friendly workplace is one that values caregiving through formal and informal means and, at a minimum, does not discriminate against caregivers; it also attempts to accommodate caregivers’ needs related to protecting and providing for care recipients. The EEOC has some guidance and limited employer regulation, but she said evidence of accommodation barriers and effective practices is needed, as existing data on what works and does not work for particular types of employee caregivers is very poor. Creative solutions might include resource groups, voluntary shift exchange, and evaluation of structural and cultural bias. Systemic reviews have provided some evidence on the benefit of psychotherapy and counseling, with the best evidence for cognitive behavioral therapy to improve coping and communication. Education, when combined with these services, may improve outcomes, she added. The evidence suggests that education alone is insufficient but works best when combined with psychotherapy and counseling. Barriers to overcome include that caregivers often do not practice self-care or mental health care for themselves. In addition, many therapists and counselors have a poor understanding of caregiving challenges.

Connection to formal services can help caregivers and recipients. The evidence differentiates between care management (the patient’s actual care) and case management (a broader array of needs), and Dr. Lerner said there is evidence that care management has positive effects for both caregivers and care recipients. In contrast, the evidence on case management does not suggest strong benefits from this, and the evidence on respite care is weak. This does not mean that respite care is necessarily ineffective, she clarified, but rather that the research has not at this point proven its effectiveness.

To engage caregivers in decision-making, Dr. Lerner cited a report (Friedman and Tong, 2020) that offers a framework to make the caregiver part of the recipient’s care team, which was shown to benefit the caregiver and the recipient. The report identified steps to mitigate barriers to greater inclusion of caregivers, such as offering incentives for providers to engage with caregivers; encouraging investment in programs offering support services to caregivers; expanding access to and funding for care coordinators; implementing training programs for providers and caregivers to facilitate effective communication; and developing, testing, and improving caregiver

access to technologies that foster greater care integration and information sharing. She concluded that academic medicine can innovate and experiment to make things better for caregivers, care recipients, and employers.

WORKPLACE CONSIDERATIONS

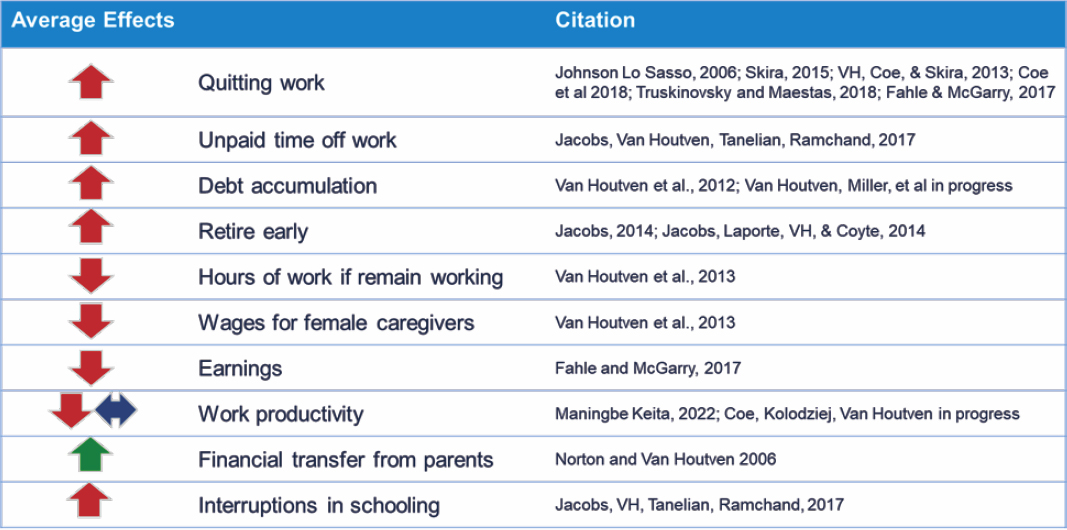

As context, Dr. Miller noted that there are about 40 million unpaid caregivers in the United States, mostly women. They experience burnout and strain that affects not only them but care recipients as well, she said. An economic valuation of caregiving should encompass not only the cost of paid workers but also costs associated with unpaid caregivers and their employers, which is challenging to capture. The average effects of caregiving on caregiver outcomes are felt in terms of health and economic costs. Focusing on the economic costs, Dr. Miller noted the effects are mostly negative for the individual caregiver and can compound over time, related to such factors as unpaid time off work, lower wages, and debt accumulation (see Figure 4-2).

The RAISE Family Caregiving Advisory Council2 put out a request for information (Nadash, Alberth et al., 2023) from caregivers through a survey and focus groups, Dr. Miller related. Key findings included support for expanding the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA; P.L. 103-3), access to paid time off and sick leave, flexible work arrangements, and supportive work environments. In a more in-depth look (Nadash, Tell et al., 2023), themes that emerged were the need for financial compensation, inability to maintain employment, concern about the availability and quality of care provided by nonfamily members, and concern about financial viability and fairness.

In addition to implementation of the federal and state policies discussed earlier (see Chapter 3), Dr. Miller said employers can implement policies including flexible schedules, family and medical leave policies, paid leave, and employee assistance programs to help address some of the financial costs of caregivers. Flexible arrangements benefit employers, too, she noted, because they retain more workers. The body of evidence about

___________________

2 The RAISE Family Caregiving Advisory Council was created under the Recognize, Assist, Include, Support, and Engage (RAISE) Family Caregivers Act of 2017 (P.L. 115-119). As part of this act as well, public comment was solicited on the 2022 National Strategy to Support Family Caregivers. More information on the National Strategy and response to public comments can be found at https://acl.gov/CaregiverStrategy.

SOURCE: Kate Miller, Workshop Presentation, February 27, 2023.

employee assistance programs is not robust, but one key piece in some data suggests workers are not comfortable talking about their caregiving status at work. As a work-around, she noted that when Fannie Mae (Federal National Mortgage Association) offered a geriatric case manager to employees, the manager was not employed by Fannie Mae, which led to more successful uptake.

Racial and ethnic disparities exist with access to unpaid leave and paid leave, which can further exacerbate inequities. For example, 7.0 percent of non-White employees reported needing to take unpaid leave but were unable to, compared with 3.4 percent of White employees (Klerman et al., 2014). Regarding access to paid leave, 26.4 percent of Hispanic and 42.8 percent of Black individuals had access to paid leave to care for an ill family member, compared with 49.4 percent of White non-Hispanic individuals (Bartel et al., 2019). Dr. Miller concluded by noting that the key policy she recommended to support family caregivers (flexible work schedules, family and medical leave policies, paid leave, and employee assistance programs), a strong focus on policies with economic supports are aligned with prior policy recommendations from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, including the 2016 report Families Caring for an Aging America (NASEM, 2016), and are aligned with the self-reported needs of caregivers. A key consideration for equitable access is ensuring not only that policies are in place and cover all workers but that all workers can access these policies.

DISCUSSION

Dr. Valantine asked about typical approaches that employers are adopting to support caregivers and the potential pitfalls of these policies and practices. Dr. Lerner said many employers assume caregiving is not a pressing issue among their employees, especially the need to care for an ill, disabled, or aging family member. She also said there is a tendency to want to manage the problem by “checking the box instead of moving the needle for change.” The programs are not fit-for-purpose or designed for the issues that many caregivers face. She also observed that some salaried and higher-paid positions are getting access to concierge services, which do not solve the long-term problem of a broken system. Anecdotally as well, the time necessary to manage the needs of caregivers who access these services has increased over time.

Dr. Miller said when designing programs, it is important to consider eligibility criteria to define family caregiving duties and relationships. It is also important that caregivers feel comfortable accessing available services, as they may be hesitant to disclose their status in the workplace for fear of discrimination. To explain the different needs of different groups and how to ensure equity among groups, Dr. Miller pointed to a literature review of international evidence (Ireson et al., 2016). One theme that emerged is that policies administered through human resources to employees at all levels of an organization, not just the upper levels, was a key component to addressing inequities and ensuring it was not only those in upper management who received support.

Dr. Lerner noted the potential to make progress because of increased attention on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in academic medicine, and the ways in which caregiving intersects with these concerns. “Sometimes we have policies in place that we think are helping people, but they are not really reaching the people who need them the most,” she observed. Looking at how caregiving policies are utilized should be part of an organization’s DEI efforts. She also called for changes in tenure and promotion, so that altering timelines, support, and criteria does not derail careers. Bridge and other specialized funding, leverage with grant sponsors so timelines are not so brutal, and other flexibility are important.

Regarding the discordance between policies and use of those policies, especially when the culture discourages using them, Dr. Miller reiterated that caregiving is normative yet remains stigmatized. Individuals often have low levels of awareness of the caregiving leave they can access, she added, citing a 2016 National Academies report (NASEM, 2016). Dr. Lerner referred to the “culture of sacrifice” among many health-care providers and other STEMM workers. She suggested looking to organizational literature for lessons to apply to academic medicine. For example, to change culture, it is necessary to think of interventions at multiple levels: individual, work-group (departmental), leadership, and organizational. Changing the culture around caregiving requires more than “little tweaks,” such as developing a broad DEI plan. Caregivers often do not self-identify as such to their employers, but employee resource groups can be the eyes and ears of caregiving within a company to suggest interventions and policies. Employers that contract with vendors and suppliers can build in accountability for caregiving services in their requests for proposals, she suggested.

Dr. Miller described her research in the VA system that may apply to academic STEMM organizations, with particular focus on two programs.3 The first, the VA Caregiver Support Program, provides comprehensive assistance for family caregivers. She explained this is a clinical intervention written into law and supports for the caregiver may include a monthly stipend, insurance, mental health services, and access to a VA coordinator. The second is the Program of General Caregiver Support Services, in which caregivers do not get a financial stipend but do receive coordination and training support.4

She shared some lessons learned from the VA. When the Caregiver Support Program started, demand outstripped expectations. There was a lot of heterogeneity in how the program was implemented across the country, so developing clear, intentional guidelines on eligibility and activities was important. The VA’s investment in resources and assessment processes could be a starting place for other organizations, she suggested. As part of the evaluation for the recipient, the VA has developed a set of measures on how to collect data and conduct reviews at multiple stages.

Dr. Lerner explained the Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregivers’ Working while Caring initiative.5 She is part of a team identifying groups of employers to form innovation labs to learn about caregiving and how it affects the workplace. A series of pilots will be implemented and aimed at improving the quality of working life for family caregivers. She noted that many of the employers are smaller to mid-sized companies, with a lot of frontline workers and minoritized populations. They range in the benefits they offer from excellent to very little, and all have shortages of employees.

Dr. Valantine asked about key policy areas that need improvement especially in academic STEMM. Dr. Lerner stressed not only looking inside an organization but also developing policies with external stakeholders. Academic medical centers and universities must build up community resources.

___________________

3 The Department of Veterans Affairs Caregiver Support Program is not a direct comparison to STEMM organizations, as this office provides support for caregivers of veterans as part of the VA health-care system rather than providing support to caregivers in the VA workforce. It is included here as an exemplar given the many programs that have been built out with caregivers in mind, that might be applied in a different setting for STEMM organizations looking to support their own workforces.

4 For more information on the VA Caregiver Support Program, see https://www.care-giver.va.gov. For information on the Program of General Caregiver Support Services, see https://www.caregiver.va.gov/Care_Caregivers.asp.

5 More on the Working While Caring initiative can be found at https://rosalynncarter.org/working-while-caring/.

Dr. Miller urged thinking of unintended consequences. For example, by giving caregiving supports, higher health-care use might increase costs.

Dr. Masur commented on the need for flexibility within the academic system, such as how many years are prescribed for each step on the career pathway. She asked about the ramifications of removing these restrictions. Dr. Lerner said changes to grants and promotion changes should be evaluated through a data-driven approach. While academic medicine is a privileged group, she commented, they do shift work, they are frontline workers, and they have high demands placed on them. In external organizational literature, she commented, these are seen as problems that reduce autonomy and flexibility. Alternatives to scheduling and shift work may come into play at different points in employees’ careers and caregiving journeys. She pointed to caregiving passports or registries used in the United Kingdom and Canada in which people register in a centralized portal to access services.

Kathleen Christensen, Ph.D., commented that to provide career flexibility over time might require structural changes. Dr. Lerner said examples include credit for community engagement, rather than being locked into publications and grants as a measure of success. Organizational research provides other examples to introduce flexibility, such as bringing in administrative or other support. Dr. Valantine noted that in academic medicine, people are in teams with different trajectories, stages of career, and focus areas, which may provide an opportunity for flexibility. Dr. Christensen commented on some movement in the private sector to negotiate on a team basis, in which everyone buys into the vision and normalizes flexibility. Dr. Kossek noted that she helped 30 corporate organizations redesign job descriptions within teams. In addition to adjusting workloads, these changes provided other opportunities for organizations, such as training junior members. She mentioned an early academic article on caregiving decisions (Kossek et al., 2001) in which she found that organizations do not know how to deal with different types of care needs, such as caring for children versus caring for dying parents. She also commented on intersectionality, in that different racial/ethnic groups and nationalities have different needs. Dr. Lerner and Dr. Miller agreed that research is needed in these areas. Dr. Lerner said she is conducting randomized controlled trials; in addition to psychological coping techniques, employees are provided with ideas and techniques about how to modify their jobs to function more effectively.

An audience member asked how to convince institutions to invest funds in caregivers. Dr. Lerner stressed the need to make the business case for intervention. Employers cannot afford not to address the issue because of the magnitude of the population and the impact on the organization, she said. Dr. Valantine agreed, although she observed that often organizations are presented with the business case and still will not change. Dr. Lerner said sometimes what they see as their most pressing issues rise to the top. It is important to stress that caregiving affects all workers to raise its importance for attention.

Stigma persists, with some supervisors seeing parenthood as a choice, an audience member commented. Dr. Miller said a multipronged approach to shift culture is required. Dr. Lerner called for interventions at all levels to understand the stigma and how it operates. As an analogy, the stigma around mental health has been dealt with most successfully by engaging leadership, bringing forth personal stories, and putting money behind the effort, she said. Dr. Valantine added that faculty internalize the stigma, with concern that one is seen as not committed or as putting extra burden on colleagues. She said one model at Stanford was a system in which people contribute and draw on leave as needed.

Some policies are well meaning yet seem not to work, and Dr. Valantine asked the presenters for examples. Dr. Lerner said she did not have complete information, but employee assistance programs (EAP) may be an example that has low utilization, perhaps because of cultural and stigma issues or perhaps because employees are not sure to whom they will be talking. They may also consider dealing with the EAP another source of strain that takes time, rather than adds value. As another example of a well-meaning policy that has challenges in implementation, FMLA is often not used out of fear of retribution. She suggested conducting dissemination and implementation research to understand issues around uptake. Dr. Miller added that FMLA results in inequitable access since it is unpaid leave. Dr. Valantine said another unintended consequence of parental leave is how some female and male faculty use the leave differently, which can widen the gap when men use it to enhance their careers, as noted earlier.

As strong exemplars to support caregivers, Dr. Miller called attention to the VA programs she mentioned, as well as the Family Resource Center at the University of Pennsylvania.6 Dr. Lerner suggested looking at other areas, such as the system to return to work after an employee’s injury or disability.

___________________

6 For more information, see https://familycenter.upenn.edu/.

Research in this area shows the positive effect of streamlined services to reenter the workforce and personal contacts, such as when supervisors call employees to remind them about their value to the workplace.

To fold caregiving into DEI frameworks and funding, Dr. Lerner suggested looking for bias against caregivers and finding ways for caregivers to report any problems to generate action. Understanding cultural differences in families and their preferences in caregiving is needed. Academic medical centers should build in a way to assess what individuals’ preferences are, she suggested—for example, how long someone needs to take a leave and the role they will be playing in providing care. Many institutions have significant numbers of international faculty who are living far from their families and who have different types of caregiving situations. Dr. Miller noted a paper by the Diverse Elders Coalition with guidelines for these situations (DEC, 2021). Dr. Valantine underscored that caregiving and DEI are intertwined and urged each institution to undergo an inquiry into the needs for its constituency, then use creative approaches and design thinking to meet those needs.