Barriers, Challenges, and Supports for Family Caregivers in Science, Engineering, and Medicine: Proceedings of Two Symposia (2023)

Chapter: 5 Research on Different Types of Caregivers

5

Research on Different Types of Caregivers

At the start of the second session of the national symposium on supporting family caregivers working in science, engineering, and medicine (SEM), Ellen Ernst Kossek, Ph.D. (Purdue University) underscored the value of the discussions to date. She reminded participants that the consensus study being undertaken by an ad hoc committee convened by the Committee on Women in Science, Engineering, and Medicine was motivated by continued barriers that all genders in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine (STEMM) face as caregivers. And, she noted, while individuals face obstacles in their career advancement, institutions and the nation risk losing out on their expertise.

In a series of individual presentations, Tracy Dumas, Ph.D. (Ohio State University) discussed caregiving for adults, as revealed in a survey of 763 female faculty; Djin Tay, Ph.D. (University of Utah) focused on the needs of those caring for family members at the end of their lives or with serious illnesses; and Lisa Wolf-Wendel, Ph.D. (University of Kansas) shared research on caregivers among faculty, with a focus on non-tenure-track and international faculty.

UNIQUE CHALLENGES FOR CAREGIVERS

Dr. Dumas drew on data compiled for a qualitative study about challenges facing academic women during the COVID-19 pandemic, conducted in collaboration with Dr. Kossek, Matthew Piszczek, and Tammy

D. Allen. Some of the data were used in a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine consensus study on the challenges faced by women in academic STEMM during the pandemic (NASEM, 2021). Dr. Dumas said she delved into the existing data for new insights for this presentation. She reviewed the open-ended responses from more than 760 women to shine greater light on caregivers in different types of situations.

OVERLOOKED CHALLENGES IN CARING FOR ADULTS

Dr. Dumas said her return to the data revealed tension between caregiving and professional responsibilities, overlaid by the perceived notion that women feel they are not seen as a fit for careers in science. For example, Dr. Dumas shared, an assistant professor commented that being told that she can shift her priorities to care for a family member “doesn’t feel right. . . . [T]elling me to shift and refocus my priorities is devaluing my identity and my sense of self in many ways.” Dr. Dumas explained that the study took place during the pandemic, but respondents stressed that the challenges had existed before. A broader theme, Dr. Dumas said, is caregivers do not feel they are getting the support they need to enact both their roles, as caregiver and as academic, fully. This sense is heightened in nonnuclear family structures or for those with caregiving responsibilities outside the present U.S. norm largely focused on childcare. Of the 763 respondents, 58.20 percent were involved with childcare, 10.40 percent with eldercare, and 3.9 percent with what the researchers called “sandwiched care,” or care of both a younger child and an aging adult/parent. Her quantitative data could not provide insight into other forms of care, but Dr. Dumas acknowledged that missing from this was non-elder adult care, or care for an adult who is not aging but may have significant mental or physical health needs. Here she provided greater context through quoting the lived experiences of some of her respondents who were not captured in the survey responses. For example, one stated, “It’s not eldercare, but care of my adult developmentally disabled son. His care is more difficult because there are not as many services.” Another overlooked category, especially for adult and eldercare, are caregivers who live a geographic distance away from their care recipient. She provided quotes on the lived experience of those who lived a far distance from those that they cared for to highlight the challenges these individuals face. One respondent noted, “My father is terminally ill in another state. I cannot fly, so the drive is 8 hours each way. Trying to manage care, his affairs, and the constant travelling is exhausting.”

Caring for older adults presents a set of psychological, emotional, and logistics issues that differ from childcare, and there are fewer established organizational responses to acknowledge the role, develop policies, and consider cultural differences, Dr. Dumas noted (Bernstein and Gallo, 2019). For example, the conventional thinking in raising children that the role will conclude in a few years with a “happy ending” may not be the case in caring for adults. Dr. Dumas said that Anne Bardoel found rates of depression are higher among those caring for spouses, parents, or other adults, often because they experience social isolation (see Bernstein and Gallo, 2019).1 Dr. Dumas also pointed to emerging research on cultural differences related to caregiving expectations. While researchers have seen increasing sharing of responsibilities by men in caring for children, they see less gender parity in elder and other adult care, including for the husband’s parents (Grigoryeva, 2017).

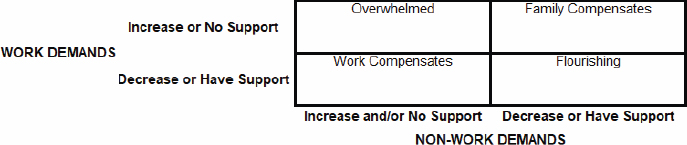

FRAMEWORK FOR SUPPORT AND DEMANDS

Dr. Dumas shared a framework for caregivers’ work demands and support that she and colleagues developed from the research (see Figure 5-1). This figure presents a two-by-two table. Along the bottom are nonwork demands and along the side are work demands, both either showing an increase in demands/no support or a decrease in demands/having support. In instances where one set of demands are decreasing/supported, the other can compensate (e.g., quadrants 2 and 3, family compensates and work compensates). In instances where both are decreasing/supported, people flourish (e.g., quadrant 4). But in instances where both are increasing/not supported, people are overwhelmed (e.g., quadrant 1).

SOURCE: Tracy Dumas, Symposium Presentation, March 27, 2023.

___________________

1 This work was discussed on a Harvard Business Review podcast, “Women at Work,” hosted by Amy Bernstein and Amy Gallo.

Referring to the graphic, Dr. Dumas said, “We want to see people flourishing in the bottom-right.” Conversely, people with decreased or no support, and with high demands, feel overwhelmed, and many exit their career path, which exacerbates gender disparities. Respondents addressing adult care or eldercare are more likely to be in more senior positions than those responding about childcare. While they may be established in their careers and have tenure, Dr. Dumas pointed out that because of additional sets of demands, they may not be advancing to leadership positions where they can make change. They may also not be able to mentor and advise junior women, which is a loss to the field, she commented.

In summarizing some of the broader issues, Dr. Dumas said caregivers need to manage expectations about their identity and image. A key theme was that most are concealing their challenges, although some said they became more transparent when they felt overwhelmed. Concealing behavior was exemplified by a participant she quoted as saying, “Research leaders do not acknowledge anything has changed with timetables and expectations. If you can’t keep up, people who have fewer responsibilities at home will be able to do it. So, I do not talk about it.” In contrast, revealing behaviors were adopted by another respondent who noted, “I am more transparent than usual about how my family roles contribute to distraction or lack of availability.” Respondents also often traded off priorities, engaged in psychological role withdrawal, or exited one or the other of their behavioral roles. While most exit their career roles if they must choose, some stated they sacrificed their family lives, including a respondent who accepted that her ex-spouse should have primary custody for their children because of her professional responsibilities. This respondent shared, “The expectations were so high that I had to agree to my children leaving my home to be at their father’s home. I have sacrificed my family for work.”

RESPONDENTS’ RECOMMENDATIONS

Dr. Dumas reported that recommendations from respondents included structural support for their tasks at work and social support from leaders and others in their organizations. “The silver lining, perhaps, is that people are intentional about advocating for change. Many said they tried to fit the ideal worker template but are now intentionally sharing their situations to advocate for others,” she said. Organizational interventions to support caregiving included administrative support, emergency and “as needed” responses, and flexibility. She urged a focus on essential deliverables,

shedding those things that informally have become part of a job but are not needed. Seeing people in leadership positions who model healthy patterns of managing work and caregiving responsibilities is also important.

DISCUSSION

Dr. Kossek asked about any findings related to virtual work. Dr. Dumas responded that virtual work alone is not the solution, especially when caring for people with additional needs and without additional workload management. Robert Phillips, Jr., M.D. (American Board of Family Medicine) commented on the heartbreaking choices that some respondents have made. He asked about policies that the committee could put forward to support caregivers. Dr. Dumas said some helpful policies were to adjust workloads either temporarily or long term, set up different timelines, and provide additional technology or other support. The challenge is overall policies do not address the needs of everyone. Managers and leaders must interface individually with workers and be able to support what they need, which she acknowledged is challenging from a policy level. The ability to customize, although challenging, is what emerges from the data, with a focus on outcomes. Dr. Kossek underscored that size matters, and customization is easier in more nimble organizations.

Sandra Masur, Ph.D. (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai) commented that organizations cannot change external conditions but must change within. One example, she said, is the decrease of support staff in universities. Providing more support would help everyone, not just those with caregiving needs. She also underscored the need for flexibility. Kathleen Christensen, Ph.D. (Boston College) commented on the need to normalize organizational responses. She pointed to Deloitte’s Career Customization Model and to Stanford University School of Medicine, both of which have normalized different ways to advance in a career. Rather than individuals having to ask for “a deal,” these models provide a structural response for all, she said.

An audience member asked about the survey respondents in the study who stated they chose to shift to advocacy. Dr. Dumas said many were fed up with expectations to continue with business as usual in difficult situations. An audience member brought up that expectations of caregiving depend on cultural background. Often, the caregivers themselves perceive they must care for family members because of cultural norms. Dr. Dumas said this is an example of a psychological and emotional challenge that may benefit from counseling and therapy.

EMOTIONAL AND HEALTH IMPACTS OF END-OF-LIFE CAREGIVING AND BEREAVEMENT

Dr. Tay began with a personal story in her role as a “distance caregiver.” While she was in the final stages of her Ph.D. program in Utah, her grandmother passed away in Singapore. Her father suffered a pulmonary embolism 2 weeks later, and both he and Dr. Tay’s mother experienced other health challenges. As the only member of the family with health-care training, Dr. Tay is called upon for advice and assistance, although she acknowledged an additional stress when family members pay more heed to information online rather than her information. As a caregiver at a distance, she explained, she provides care coordination, as well as emotional and financial support. She is also navigating the early phase of a tenure-track position and is the single parent of three children. “I don’t tend to share information about my personal life, but I recognize these experiences shape who I am and have shaped my research interests,” she said.

Dr. Tay highlighted research on end-of-life caregiving, bereavement, and spousal cancer caregiving, which she has studied with several teams. The findings are similar to other aspects of caregiving, but they may have a more intense context than caregiving for people with more chronic conditions or for diseases with a slower trajectory of decline, she posited.

CANCER CAREGIVING

Globally, the prevalence of depression is 4.4 percent, and the prevalence of anxiety is about 3.6 percent. Among cancer caregivers, both rates are substantially larger—42.3 percent with depression and 46.55 percent with anxiety. In a study of caregivers of patients with advanced cancers who had received immunotherapy treatments, caregivers had lower optimism and more anxiety about the outcomes than the patients themselves.

Certain phases of cancer caregiving are more burdensome. In a hospice study in which she was involved (Tay, Iacob et al., 2022), caregiving burden was associated with anxiety and depression. Younger caregivers experienced greater anxiety and caregivers with lower financial and social support experienced greater depression. This is particularly significant for student caregivers. These students are disproportionately women, enrolled part-time, graduate students, and receiving financial aid. Seven in 10 say that caregiving affects their academic achievement and that they experience anxiety and depression. Potential strategies to improve support include

more frequent assessment, understanding, and flexibility from mentors, as well as wellness support. Two innovative strategies at her institution are a student hardship fund (led by students for students in need) and scholarships targeted to family caregivers.

TIME STRAIN

While the time spent caring for family members at the end of life can be meaningful, it also imposes a strain on caregivers. A study of self-care among caregivers with a family member in hospice (Tay, Reblin et al., 2023) found that almost one-half reported they did not have time to exercise, rest, or slow down when sick, and about one-third reported they had missed at least one of their own physician appointments in the past 6 months. Better mental health is associated with taking the time for these self-care behaviors, Dr. Tay commented. In the models constructed related to caregiving and activities of daily living, the researchers found men hospice caregivers had lower odds of being able to rest when they were sick than did women. Although this is just one study, she said this finding suggests that the implications of gender may be nuanced. Reasons to explore in further research may be that these men caregivers are less aware of the need for self-care, have smaller support networks, or have greater competing demands at work.

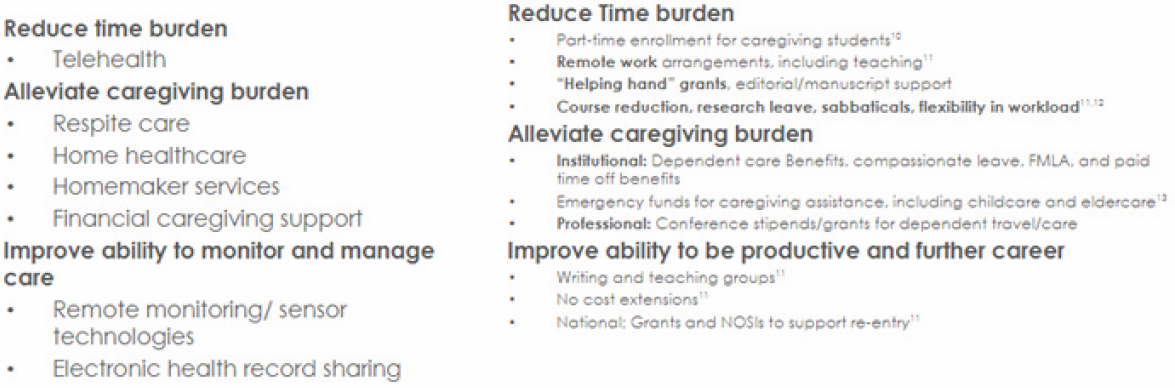

Dr. Tay highlighted research (Xu et al., 2023) about the effects of employment on family caregivers. Working during end-of-life caregiving served as a moderator for caregivers’ health, but these workers also had lower productivity. “These juxtaposing findings suggest that role diversity may help individuals cope with some of the challenges of caregiving, but it affects their work,” she said. She noted research on caregivers in STEMM during the pandemic found that women spent less time on research than they had planned; had more difficulty than men in doing highly cognitive work such as analyzing data, writing grants, and managing their time; and had to balance household, work, and family responsibilities (Skinner et al., 2021). Interventions to support caregivers in these instances include those that reduce time burden, such as telehealth; alleviate the caregiving burden, such as respite care and financial support; and improve ability to monitor and manage care, such as remote monitoring. She reported on strategies to support caregiving STEMM professionals including those to reduce the time burden, such as remote work or course reduction; alleviate the caregiving burden, such as dependent care benefits or support for dependent care to attend conferences; and improve the ability to be productive, such

as writing and teaching groups and no-cost extensions for grants. She noted that it is important to ensure that students, adjunct faculty, and others also have access to these types of support.

POPULATION HEALTH OUTCOMES

Dr. Tay has worked with Katherine Ornstein, Ph.D., on an end-of-life study using population datasets from Denmark and Utah. Using Denmark population registers, members of Ornstein’s team characterized family networks and the effect of bereavement such as in the use of antidepressant drugs and psychological services. Dr. Tay built on this work with a focus on those who previously had experienced mental illness (Tay, Ornstein et al., 2022). Across these studies, the data showed that spouses and partners are at the greatest risk, especially in the first 3 months after the death of a partner. She pointed out that mental health is a serious and underaddressed issue in academia, and bereavement can be an acute stressor that can exacerbate preexisting mental health conditions.

The Denmark study paved the way for a population-level perspective in the United States using the Utah Caregiving in Population Science (Utah C-Pops) database. One of the first papers from this study looked at how family structure affects end-of-life outcomes (Tay, Ornstein et al., 2022), and other papers are under review. Building on this research, she and colleagues are establishing a cohort of cancer patients and spouses. One of the goals is to figure out how to support cancer caregivers’ physical and mental health.

IMPLICATIONS FOR ACADEMIA

Dr. Tay noted that while more women have doctoral degrees compared with men, they are less likely to get tenure and promotions. Extending the tenure clock became a more visible option with COVID-19, but she noted the downstream implications include negative effects on income, promotion, and career progression, as well as opportunities for leadership and grants. Pausing the tenure clock may reduce the pool of tenured women faculty and increase the pool of tenured men faculty. She also noted equity implications, such as the needs of non-tenure-track faculty, including minoritized women who are most likely to be in these positions.

Dr. Tay identified technologies and strategies that can be helpful (see Figure 5-2), but they will not change the culture of academia, which is not

SOURCE: Djin Tay, Workshop Presentation, March 27, 2023.

set up to support family caregivers. She said it is important to change the culture to attract and retain talent in STEMM. Trainees are looking at those already working in the field as they decide whether to pursue a career in academic STEMM. She noted in one study of engineering and computer science doctoral students and graduates who did not pursue an academic career, 69 percent said it was because of the stress they perceived (McGee et al., 2019). Dr. Tay urged acknowledging and addressing gender bias, as well as increasing the visibility of caregiving and distributing professional responsibilities more fairly.

Dr. Tay shared a quote from Rosalynn Carter: “There are only four kinds of people in the world. Those who have been caregivers, those who are currently caregivers, those who will be caregivers, and those who will need a caregiver.” Dr. Tay concluded that she still regrets not having returned to Singapore for her grandmother’s illness and funeral in 2016. She was in her final year of her Ph.D. program and did not travel because of the costs but also her concern that her U.S. visa would not be extended if she needed more time to complete her doctoral work. Others, especially those with international backgrounds, share these pressures. “I hope as a field we can change the culture and practice the principles that we preach—diversity, inclusion, and flexibility when it comes to caregiving,” she said.

DISCUSSION

Dr. Kossek began the discussion by noting the number of foreign-born faculty in STEMM. Already juggling institutional and family pressures, the uncertainty around immigration is added, and she asked Dr. Tay what could be done. Dr. Tay concurred that living in another country adds a level of complexity to navigate. Some people “tough it out” to achieve, but if the environment is not supportive, some will leave and find jobs closer to home. Joan Williams, M.A., J.D. (University of California, San Francisco) echoed that hearing about personal experiences and data brings home the human toll. She recalled a qualitative study she conducted about 12 years ago on science professors who are women of color and found the parents of many Chinese professors came to help with childcare, but many also need to receive care as they age. Ms. Williams also posited that the finding in Dr. Tay’s study that men hospice caregivers do not take leave when they are sick may in part be because men in general tend not to take time off when sick.

Dr. Christensen asked how funders could help support caregivers from other countries, especially those caring for people at the end of life. Dr.

Tay suggested an in-depth awareness of the visa concerns of international trainees would be helpful. For grants, a more holistic view of the challenges is needed, especially for unsupported caregivers, which disproportionately affects women. Reflecting on remote work and flexible scheduling, Dr. Tay said those with needs to work remotely should be heard. She also suggested being cognizant of when meetings are scheduled and how long they last. Lastly, she noted that even if a person has money to pay for a caregiver for respite or temporary care (such as a babysitter), such a person may not be found.

An audience member in a tenure-track position at an R1 university commented that when they bring up caregiving challenges, their supervisor minimizes the situation. Dr. Tay stressed that more needs to be done to acknowledge the value of caregivers in academia and the benefit of lived experience to the institution. She added that caregiving must be seen as an aspect of inclusion because it affects everyone. Hard data, such as how caregiving affects grades or retention, are important to get leadership buy-in, she concluded.

MANAGING ACADEMIC CAREERS AND CAREGIVING

Dr. Wolf-Wendel shared research with a focus on the needs of international and contingent faculty, and possible systemic fixes.

TERMINOLOGY AND BASIC CONCEPTS

Commenting on terminology, Dr. Wolf-Wendel said that she does not use the term work-life “balance” because, to her, this sets up an ideal worker norm. She instead uses the terms “integration” or “management.” Similarly, she uses the term “work-life” rather than “work-family” because all faculty are entitled to a satisfying life outside of work. Reflecting the different people who may need care, she uses “caregiver” rather than “parent,” and noted that while women are more likely to be primary caregivers, men also face problematic norms. Finally, she stressed the need to change norms and policies, not people. When you have a leaky pipeline, fix the pipe, not the water, she asserted.

Understanding academic life requires understanding such frames of reference as ideal worker norms and entrenched gender roles, Dr. Wolf-Wendel continued. She said her research focuses on a life-course perspective, not just a focus on the period when a parent is giving birth or adopting a child. A

challenge is the neoliberal university structure, she asserted, in which budgets are determined by things that can be counted, like grants and student numbers, with a culture of doing more with less, an orientation to deal with crises, and historical exclusiveness.

Work/life integration encompasses diverse circumstances and considerations, related to career, family structure, and a range of needs, Dr. Wolf-Wendel said. “We enter into caregiving with different constructions but also differences in identity and the way we navigate work and life,” she said. In addition, the academic institution makes a difference, such as whether a caregiver is working at a 2- or 4-year institution, their discipline, and their career stage.

Those in tenure-track positions follow an “academic career life cycle” that begins in graduate school, she said. Women earn about 50 percent of STEMM doctorates with the expectation that students will go on to a postdoc position, then enter a tenure-track position. However, women are only about 25 percent of STEMM tenure-track faculty. To understand the changes over time, Dr. Wolf-Wendel interviewed 120 pre-tenure women, then interviewed them at 7-year intervals through their early, mid, and late careers. The early career is characterized by the biological and tenure-track clocks. In addition to the challenges, Dr. Wolf-Wendel stressed that respondents also talked about the joys of being an academic mother. She observed the need to discuss these benefits, not just the hardships. Early-career women need mentorship and sponsors, and supportive policies and practices, Dr. Wolf-Wendel said. At mid-career, the points often raised were about scheduling, because many were involved in research, teaching, service, and caregiving. For this reason, some said they were hesitant to go up for promotion to full professorship, but they have a feeling of being stuck. Not all STEMM faculty work is the same, Dr. Wolf-Wendel commented, such as if one is managing a lab versus doing field work. Extra layers are added in managing grants and in clinical work for those in academic medicine. Dr. Wolf-Wendel commented that some STEMM fields have more options for employment outside the academy.

INTERNATIONAL, DUAL-CAREER, AND CONTINGENT ACADEMIC CAREGIVERS

According to Dr. Wolf-Wendel, about 20 percent of STEMM faculty are foreign-born and they represent one-third of all new hires, a higher number than women or underrepresented minorities. The exact number

is hard to determine because of different types of visas and immigration status. To try to understand international faculty needs, Dr. Wolf-Wendel and a colleague used a survey conducted by the Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education, or COACHE, survey 2012–2018, which covers 67,000 faculty from 164 universities.2 It does not completely disaggregate by nationality, but it does compare U.S. (88 percent of the total) and non-U.S. citizens. Ten percent of all respondents were caregivers for adults. International faculty were more likely to be married with children. Related to work/life characteristics, international faculty were less satisfied, but more productive; by contrast, there was a correlation between satisfaction and productivity for U.S. faculty. International faculty were less mobile and less likely to hold leadership positions. Although not addressed in the survey, Dr. Wolf-Wendel noted that many international faculty are concerned about racial and ethnic targeting and feeling invisible or misunderstood.

A high percentage of women in STEMM are part of dual-career couples, which affects mobility and the likelihood of a tenure-track job. Women, including international women, are more likely to accompany spouses and opt for non-tenure-track positions if necessary. Among international tenure-track faculty, two patterns emerged: either a mother or mother-in-law lives with the family to assist in caregiving, or the faculty member lives far away from all family members.

Dr. Wolf-Wendel commented on non-tenure-track faculty, whom she termed the “fast-food workers of the academy.” While some part-time faculty are retired or work elsewhere, others are trying to piece various positions together to earn their living. Full-time, non-tenure-track faculty also include research scientists and teaching faculty, as well as those working on grants or short-term contracts. Non-tenure-track positions now represent two-thirds of all faculty, she said. They are not spread evenly across institutions, with more at community colleges, but they are also replacing full-time, tenure-track positions at many 4-year universities. Women and underrepresented minorities are more likely to fill these positions, which Dr. Wolf-Wendel referred to as the “Glass Wall.” They are paid less, work more, have marginalized status, and have no work/life recognition or benefits. They are often cut off from rejoining the tenure-track career ladder. The irony is that some choose this role to care for families because of the potential flexibility in work, but no policies cover their caregiving roles, that is, when they don’t work, they don’t get paid.

___________________

2 For more information on COACHE, see https://www.facultydiversity.org/home.

Dr. Wolf-Wendel said recognition by institutions is slowly growing of the needs of full-time, non-tenure-track faculty. Examples include development of career ladders, such as the Delphi Project at the University of Southern California, as well as paid family leave and career development, some brought about by unions.3 She also called attention to “vampirism”: in a dual-academic family in which the husband is on the tenure track and the wife is in a contingent position, the wife contributes to the husband’s research, but he publishes under his name. Permeable boundaries between the public and private spheres were revealed during COVID-19, as was the inequitable division of labor among heterosexual couples.

DISCUSSION

Elena Fuentes-Afflick, M.D., M.P.H. (University of California, San Francisco) brought up the lens of academic medicine. Productivity is emphasized, with every minute accounted for, which brings distinct pressures. She also noted that only 9 percent of the 4,200 faculty at her institution are on the tenure track. Dr. Wolf-Wendel said she learned of innovations in academic medicine at Stanford, with different foci at different stages of one’s career. She noted that she conducts a coaching circle of mid-career faculty, and some delay going up for promotion because their institutions have asked them to take on other service responsibilities.

Ms. Williams commented that some argue that stopping the tenure clock hurts women under the assumption that they would otherwise continue on an accelerated path. However, she said, empirically, some might drop out completely without this option and asked about data on tenure-clock decisions. Dr. Wolf-Wendel commented that these policies are not as widely used as she expected, often because department chairs and deans do not know about them. She said the policies must be regularized so they do not simply exist but are used, as well as compensate for salary differentials. Dr. Christensen urged rethinking the tenure system. “We have to think outside the box, not that existing policies are the only way to do things,” she said. Dr. Wolf-Wendel agreed with the need to look at alternatives but warned that some might use this focus to eliminate tenure, which would affect academic freedom and shared governance.

Dr. Masur commented on the needs at early, mid, and later careers, and pointed to the falloff at mid-career. Dr. Wolf-Wendel said she recently did a

___________________

3 For more information on the Delphi Project, see https://pullias.usc.edu/delphi/.

study of gender differences in who becomes a department chair. Women are more likely to be appointed as chairs when they are associate professors and men as full professors. Among 17 measures of work/life satisfaction, 13 were statistically significant between men and women chairs. Mid-career women may be brought in to take on leadership roles in precarious situations, and some may derail their careers as a result, especially for women of color. She urged career development so that women achieve full professorship before they take on these types of positions for the good of their own careers. Moreover, the longer a person stays at the associate rank, the less likely they are to become a full professor. She also noted that at mid-career, women are more likely to wait to be asked to “go up” for promotion, while men tend to take the initiative themselves. Perhaps mentoring across institutions within disciplines can help, she suggested. She noted more research and interventions for mid-career, such as National Science Foundation ADVANCE grants, research on mid-career faculty by Vicki Baker at Albion College, and development resources from the National Center for Faculty Development and Diversity, or NCFDD.4

___________________

4 For information on National Science Foundation ADVANCE, see https://www.nsf.gov/crssprgm/advance/. For information on Dr. Baker’s publications, see https://www.albion.edu/faculty-story/faculty-profile-vicki-baker/. For information on NCFDD, see https://www.facultydiversity.org/home.

This page intentionally left blank.