Critical Issues in Transportation for 2024 and Beyond (2024)

Chapter: Funding and Finance

![]() Foundational Factors and Policy Levers

Foundational Factors and Policy Levers

Funding and Finance

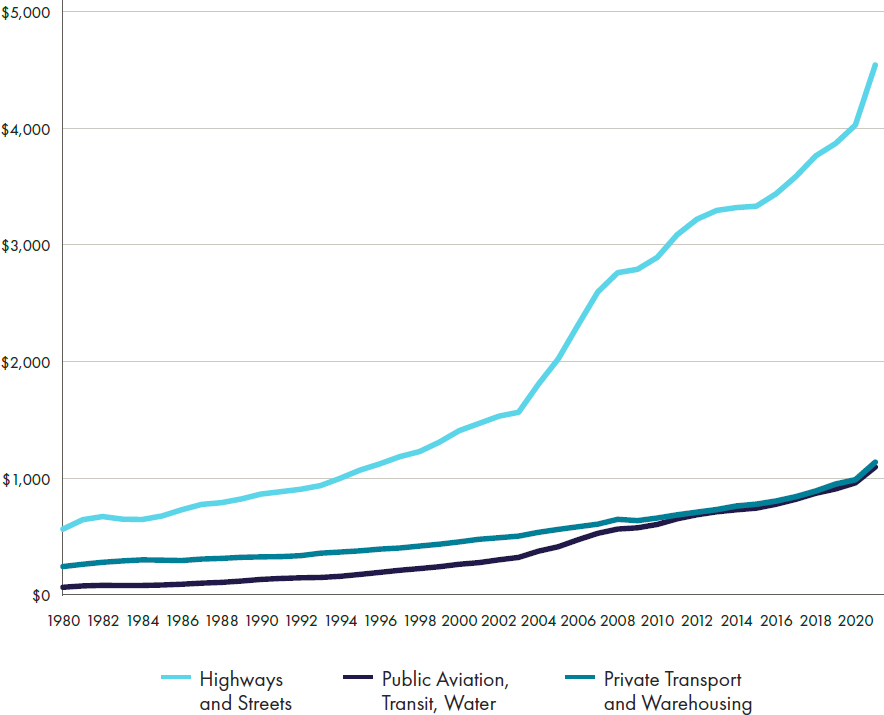

Public infrastructure (primarily highways and streets) had a value of $5.5 trillion in 2021 after adjusting for depreciation, or wear and tear (see Figure 16). Private transportation fixed capital stock (infrastructure and structures) also adjusted for depreciation, was valued at $1.1 trillion.172 The robustness of mechanisms for funding or financing the expansion and upkeep of this $6.6 trillion in assets should be of great interest given their importance for the economy and personal and freight travel. Moreover, the mechanisms for funding and financing different elements of transportation infrastructure system directly affect equity.

SOURCES: Bureau of Economic Analysis. National Data: Fixed Assets Accounts Tables, Table 3.1s for Private Structures and Table 7.5 for Government Fixed Assets. https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/?reqid=10&step=2&isuri=1.

NOTE: 1980 = 1.

SOURCES: Bureau of Economic Analysis. Table 1.1.5 (for GDP), Table 7.5 (for government investment), https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/?ReqID=10&step=2, and Detailed Tables—Investments in Non-Residential Fixed Assets (structures only for private transportation industry).

At a highly aggregate level, growth in government and private industry infrastructure investment since 1980 provides a mixed picture compared to economic growth (see Figure 17). Growth in private investment in structures (both infrastructure and buildings) lagged GDP growth until about 2010. After demand slowly recovered from the “Great Recession” (late 2007 to mid-2009 with slow employment growth for years afterward), private transportation companies do not appear to have been constrained in their ability to reinvest in infrastructure and buildings.

Government investment in transportation infrastructure for airports, transit, and waterways has grown faster than GDP since 2000, which may be due to airport expansions and new rail transit lines.173,174 Although

indicated as government investment in Figure 17, the improvement and expansion of commercial airport facilities are financed through bonds repaid by users and therefore do not draw from state or local tax bases. In contrast, government investment in highways and streets, which is far larger than any other investment in transportation infrastructure, has grown more slowly than GDP since roughly 1990. This slowdown accompanied the completion of most of the Interstate highway system in 1992. It is not clear whether the slower investment growth since then has constrained demand. In recent decades, the U.S. economy has become more service-oriented and less dependent on moving freight for heavy industry. However, as noted in the Infrastructure Systems section, congestion on Interstates and other intercity highways has grown and is projected to worsen. Other analyses indicate that significantly larger investments are needed to maintain the condition and performance of the Interstate highway system, other major highways, and transit in the decades ahead.175,176

Funding for capital investments in, and maintenance of, public infrastructure depends on available revenues from myriad federal, state, and local revenue sources, which are based on fuel taxes and other fees imposed on users, as well as a variety of public taxes, both general and sales or other tax revenues dedicated to transportation purposes. Financing (forms of borrowing) for capital investments draws on direct charges such as tolls imposed on users as well as future revenues from some of the same sources as those used for funding to repay bond holders and lenders. Roughly 40 percent of total U.S. road and highway funding—more than $100 billion annually—derives from motor fuel taxes paid by highway users.177 Capital investments in Interstates and major intercity highways and transit rely heavily on federal funding. Commercial airports are largely self-financed, but also rely on the federal Airport Improvement Program for new or expanded runways, residential noise mitigation, and other capital expenses. Federal highway and transit capital funding is primarily derived from federal transportation motor vehicle fuel taxes and fees that provide 85 percent of the revenues for the federal Highway Trust Fund (HTF). Aviation and airport funding relies heavily on a variety of user taxes and fees on commercial and general aviation that provide the revenues for the Airport and Aviation Trust Fund.178

Congress has not raised federal highway user fees, which support the HTF, in 30 years, during which time the purchasing power of HTF revenues has sharply eroded. Congressional changes to aviation user fees since the early 1990s have included a decline in the ticket tax paid by commercial aviation users from 10 percent to 7.5 percent, combined with increases to a variety of specific fees for targeted uses.179 Rather than increase user fees to fund capital investment for state highway programs, urban transit, and aviation, since 2010 Congress has increasingly relied on general funds derived from all taxes. The IIJA, which also draws heavily on the General Fund of the Government, will significantly boost federal funding through 2030.

However, these future federal commitments in the IIJA are being funded in part by spending far more than existing general taxes bring in. The 2023 federal budget deficit is projected to reach 98 percent of GDP, double the average for 1973–2022, and is projected to continue to grow through 2033.180 Emerging efforts to constrain federal spending may well put pressure on future federal funding support for transportation infrastructure.

States depend heavily on their own highway user fees for capital investments, primarily fuel taxes, which have declined in recent years due to increased fuel efficiency and will decline even more as the vehicle fleet becomes more electrified. Registration fees on EVs or road user charges (RUCs) may emerge as replacements for fuel taxes. In recognition of the heavy dependence on motor fuel taxes for federal and state highway revenues and threats to these revenues from increasing fuel efficiency, in 2016 Congress provided $95 million for a majority of states to experiment with RUCs to supplement or replace motor fuel taxes.181 RUCs and other forms of tolling have many advantages, such as charging the users who benefit from the facility directly rather than deriving funding from taxes paid by non-users, and RUCs or tolls that vary with congestion also improve traffic flow.182 However, care must be taken to address inequities that RUCs can raise. They currently lack broad public understanding and support, even though both are growing.183 Congestion tolling of new lanes on Interstates and other highways is expanding across the country. Large cities are seeking options to pay for both the capital and operating expenses of transit systems—one example of which is road congestion fees in areas of New York City to help fund the nation’s largest transit system.

The main federal funding program for airport capital improvements—the Airport Improvement Program—has remained flat since 2000 at approximately $3.3 billion. Because of inflation, the buying power of this annual investment at the time of this writing in 2023 was about half what it was in 2002. Congress has not allowed an increase in the Passenger Facility Charge on airplane tickets since 1994, and most existing revenues from this charge are required to pay for past bond issuances. Revenues for Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) operation of air traffic control and the equipment, facilities, and air traffic controllers that it requires have grown,184 but not as fast as demand has increased.

Marine transportation depends on port facilities for transfers from ships and barges to land modes. Other than highway access, the main use of federal funding for coastal ports is for maintaining and deepening harbors and waterways. These ports vary widely in terms of public or private ownership and operation and depend on user fees and some state and local tax revenues for their operational costs. Ports on inland waterways are similarly varied, with funding for locks and dams shared between federal and user fee–based revenues.