On-Bridge Stormwater Treatment Practices: A Guide (2024)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Background

The treatment of stormwater runoff on bridges is a challenge for state departments of transportation (DOTs), primarily due to physical and safety constraints associated with implementing, operating, and maintaining treatment devices. As a result, stormwater runoff from bridges is most often routed to abutments for treatment, addressed through off-site mitigation, or simply not treated. These guidelines follow from NCHRP Report 474: Assessing the Impacts of Bridge Deck Runoff Contaminants in Receiving Waters (Dupuis 2002a and 2002b) and NCHRP Report 778: Bridge Stormwater Runoff Analysis and Treatment Options (Taylor et al. 2014a).

NCHRP Report 474 reviewed scientific and technical literature addressing bridge deck runoff and highway runoff, focusing on the identification and quantification of pollutants in bridge deck runoff and how to identify the impacts of bridge deck runoff pollutants on receiving waters using a weight-of-evidence approach (Dupuis 2002a and 2002b). Although undiluted highway runoff can exceed federal and state ambient water quality criteria, this alone does not automatically result in negative effects on receiving waters. NCHRP Report 474 found no clear link between bridge deck runoff and biological impairment in the receiving water, though it noted that salt from deicing could be a concern (Dupuis 2002a and 2002b). NCHRP Report 474 concluded that long-term untreated bridge deck discharges do not have an adverse impact on aquatic toxicity or sediment quality in the vast majority of cases (Dupuis 2002a and 2002b). Still, in waterways that are subject to total maximum daily load (TMDL) allocations, source water protection requirements for drinking water, or other stringent water quality criteria, treatment of bridge deck stormwater runoff could be required.

NCHRP Report 778 found that wherever possible, the best option for treating bridge deck stormwater is to route it to land or provide offsetting mitigation via a treatment project elsewhere (Taylor et al. 2014a). This report highlighted many of the key constraints that are detailed further in this Guide, including design complexity, operations and maintenance (O&M) complexity, safety and structural risks, limited benefit, and very high cost. However, where off-site mitigation is unacceptable due to water quality restrictions placed on the receiving water body or site-specific conditions making the piping of bridge runoff to bridge ends for off-site treatment infeasible or undesirable, stormwater designers may need to evaluate on-bridge stormwater treatment. NCHRP Report 778 includes a set of spreadsheet-based best management practice (BMP) evaluation tools to evaluate stormwater volume, pollutant load removal, and cost implications for five types of treatment BMPs that could be used for treating stormwater runoff from bridges. Four of the BMPs included in the tool (swales, dry detention basins, bioretention, and media filters) are intended for use at bridge abutments, and one (permeable friction course) is intended for use on the bridge deck. Stormwater treatment designers have very few proven options for effective on-bridge treatment of stormwater and extremely limited experience applying these BMPs on bridges.

Purpose and Scope of This Guide

Before using this Guide, it is important to ask whether there are any other options besides on-bridge BMPs that can meet project objectives. The findings from NCHRP Report 474 (Dupuis 2002a and 2002b) and NCHRP Report 778 (Taylor et al. 2014a) describe the extreme challenges faced and the limited benefits that can be gained from bridge runoff treatment, particularly using on-bridge BMPs. The extensive research and case studies conducted as part of this project have yielded similar findings to NCHRP Report 474 (Dupuis 2002a and 2002b) and NCHRP Report 778 (Taylor et al. 2014a) and further detailed the array of technical, operational, and financial challenges that come with on-bridge stormwater treatment. The research team finds that there are rare cases where on-bridge treatment is feasible. Yet, a design team could spend a large amount of their budget in attempting to find workable solutions, only to arrive back at the conclusion that this is a far inferior solution to other options. If other options have not already been explored, the user should consult the guidance and findings of NCHRP Report 474 (Dupuis 2002a and 2002b) and NCHRP Report 778 (Taylor et al. 2014a) or other applicable local guidance and policy to determine if other options should be explored.

This Guide is predicated on the assumption that all other options for stormwater control from bridges have been exhausted. The primary users of this Guide are bridge and hydraulic designers working at the conceptual or preliminary design phase on a particular bridge that has been identified as requiring on-bridge stormwater treatment. The purpose of this Guide is to support DOT practitioners in:

- Setting objectives for on-bridge stormwater treatment, including minimum thresholds to mitigate risks and determine feasibility,

- Assessing bridge characteristics to determine opportunities and constraints, including identification of fatal flaws that could prohibit further development of an on-bridge option,

- Selecting, siting, sizing, and designing on-bridge BMPs and determining O&M needs to form preliminary design alternatives,

- Making key decisions regarding preliminary design alternatives, including if there is any option that adequately mitigates risks and meets thresholds to be carried forward, and

- Determining the scope of detailed design studies necessary to advance a design.

This Guide is intended to help design teams develop effective designs and mitigate risks where possible; however, it also serves as a resource for design teams to efficiently identify conditions that are fatal flaws so that effort is not wasted in further design development.

As part of scoping this research and this Guide, the investigators and Project Panel worked to define the scope and focus of the Guide to align with this purpose. These are summarized as follows:

- This Guide is focused on circumstances where on-bridge stormwater treatment is required. This could arise from a combination of regulatory requirements, design goals, and physical or operational constraints where the more practical approaches proposed in NCHRP Report 474 (Dupuis 2002a and 2002b) and NCHRP Report 778 (Taylor et al. 2014a) are not applicable or not adequate. This Guide does not cover the decision process of whether on-bridge stormwater treatment is needed or whether other options are available. Readers should refer to NCHRP Report 474 (Dupuis 2002a and 2002b) and NCHRP Report 778 (Taylor et al. 2014a) for additional guidance on those topics.

- On-bridge treatment could be required as part of a new bridge or as a retrofit to treat runoff from an existing bridge. Because existing bridges are far more numerous and more challenging,

- This Guide focuses on the processes of technology selection, preliminary design, alternatives analysis, and feasibility assessment of BMPs. This Guide does not provide detailed design guidance, which was beyond the scope of this research and will inherently be site-specific and DOT-specific.

- While the structural capacity of bridges to bear additional weight is a key consideration and is addressed in general, each bridge is unique. Structural engineers should be engaged early in the design process when considering any on-bridge BMP. This Guide identifies points at which input from structural engineers is needed.

- This Guide is focused on providing non-proprietary stormwater treatment options. The potential role of proprietary technologies is introduced in this Guide as options that DOTs may consider, but the goal of this Guide is to provide options that do not depend on proprietary treatment technologies.

- This Guide covers the BMP itself as well as the broader system of stormwater collection, conveyance, structural support, O&M elements, and other design features necessary to capture and treat stormwater. The overall system is referred to as the on-bridge stormwater treatment system.

- Permeable friction course (PFC) is a potential candidate for bridge decks that has been considered as part of previous research on bridge deck runoff (Taylor et al. 2014a). This could complement other treatments by reducing influent loads and potentially delaying clogging. However, the purpose of this project is specifically to review additional treatment practices beyond PFC. Therefore, PFC is not considered further.

this Guide focuses on retrofits of existing bridges. However, similar concepts could be applied to new bridges.

New Research Conducted

This research built on the findings of NCHRP Report 474 (Dupuis 2002a and 2002b) and NCHRP Report 778 (Taylor et al. 2014a). As part of this effort, the research team performed new research into key areas to help advance practical guidelines:

- Assessment of a broad range of conditions and constraints that exist in the highway bridge environment through a review of constructed bridges and a series of case studies, some of which are included in this Guide.

- Review and selection of treatment technologies, including review of scientific literature, resulting in a candidate filter media to use in on-bridge BMPs.

- Risk-based assessment of stormwater treatment design alternatives and O&M paradigms, resulting in articulation of the design objectives for a stormwater treatment system and development of a prototype BMP.

- Laboratory testing of filter media to determine key parameters for water quality treatment performance and O&M frequency, including extension of these findings to develop design criteria and bridge-specific sizing methods.

- Refinement of BMP options based on laboratory testing.

- Case study analyses to develop and vet a stepwise design approach and provide examples of how common elements of a stormwater treatment system can be configured to meet site-specific objectives and constraints.

The research process is detailed in NCHRP Web-Only Document 401: Developing a Guide for On-Bridge Stormwater Treatment Practices, which can be accessed on the National Academies website (nap.nationalacademies.org). This Guide is intended to distill the key findings from this research to support DOT users assessing on-bridge treatment at individual bridges.

Template Planning and Design Process

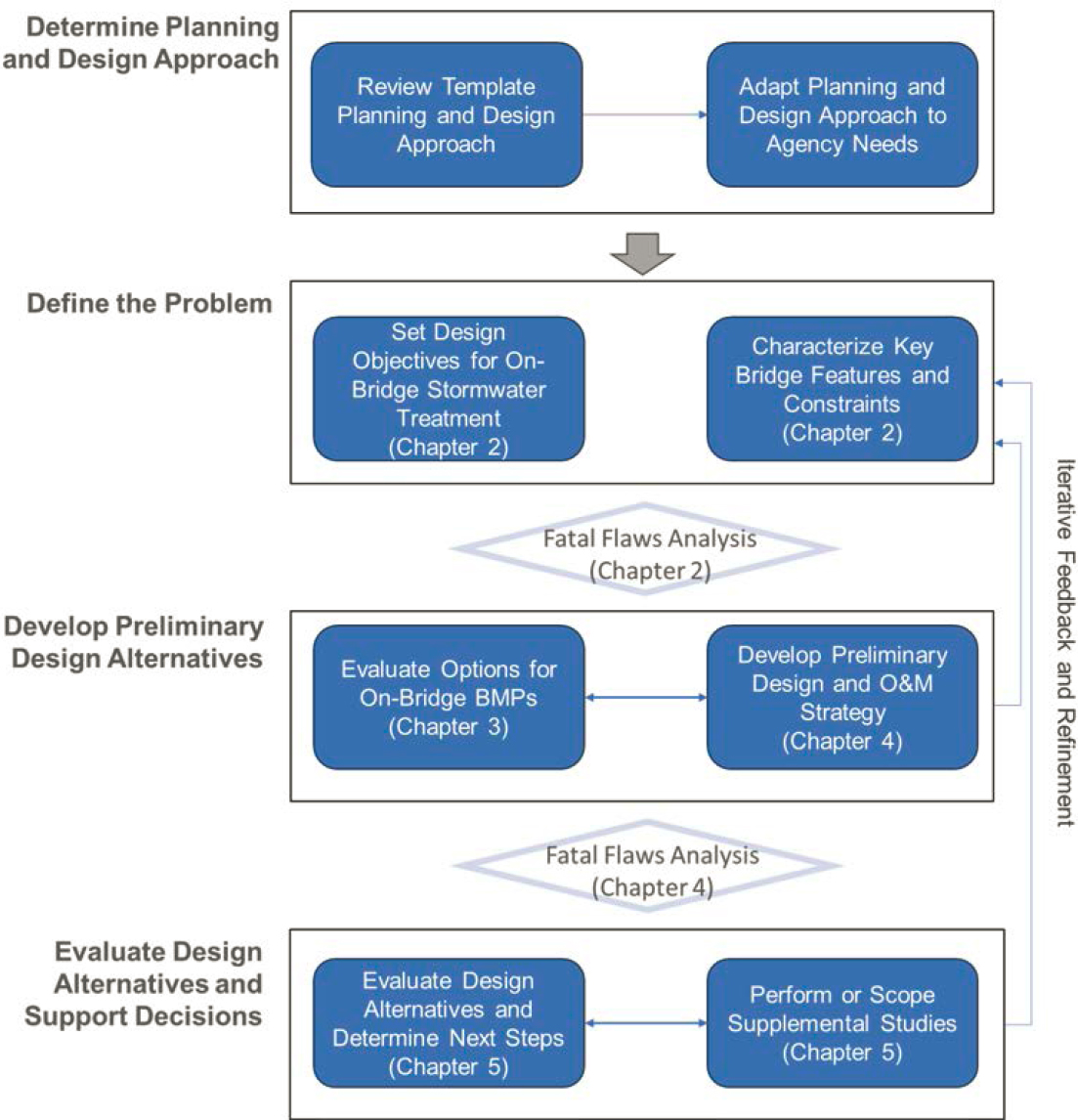

This Guide is organized based on classical phases of the engineering design cycle and is intended to be aligned with typical DOT planning and design processes. Figure 1 provides an overview of the planning and design process to advance a project from initiation through preliminary design and supporting decisions about whether an on-bridge stormwater treatment approach can and should be advanced further.

The problem of trying to incorporate stormwater treatment on bridges includes a variety of diverse conditions and constraints that must be evaluated and considered to arrive at intermediate decisions and the final design. While no two design processes are the same, a systematic approach to design development helps ensure that different disciplines and departments understand coordination needs, necessary information is collected at the appropriate time, and decisions are defensible and transparent. A systematic design approach may also be important in justifying findings of infeasibility to regulators, where applicable.

The adaptation of the template design process is encouraged. The first step in this approach is to review the template planning and design process, including the steps outlined in subsequent chapters, and determine how it can be adapted to a particular DOT and project of interest. Key drivers for adaptation of this process may include:

- Knowledge of key limitations that are believed to be fatal flaws. The process could be adapted to focus evaluation on these areas to reach efficient conclusions and avoid wasted effort.

- DOT preferences about the sequencing of studies and design efforts. For example, how rigorously existing conditions will be studied before preliminary designs are developed.

- Need for more direct linkage to the specific phases of project development that are familiar to the DOT of interest.

- Specific work products that will be prepared to document the outcome of steps.

- Identification of DOT organizational units involved in the design and respective roles.

- Identification of stakeholders that need to be involved in the process.

- Specific criteria that will be used to assess feasibility.

The remainder of this Guide is organized as follows:

Chapter 2: Characterization of the Bridge Environment for Stormwater Treatment, is intended to help a user define and constrain the engineering problem to be solved. This chapter proposes a set of stormwater treatment design objectives adapted to the bridge environment and identifies the primary constraints that inform the design process. It provides guidelines for the assessment activities and information needed to describe existing conditions and determine how these conditions influence project design. This chapter concludes with a decision gate to determine if there are fatal flaws that would prevent the design from proceeding.

Chapter 3: Stormwater Treatment Practice Design Options, guides the user on the selection and design of BMPs in the bridge environment. This chapter focuses specifically on the BMP itself as one element within an overall stormwater capture and treatment design. This chapter describes the proposed filter media and prototype non-proprietary BMP design developed as part of this research project, including key design parameters and O&M needs. This chapter also provides guidelines regarding the potential role of proprietary technologies in an overall bridge deck runoff design.

Chapter 4: Preliminary Design of On-Bridge Stormwater Treatment Systems, describes a step-by-step methodology for developing an overall system to capture, convey, and treat stormwater. This chapter builds on the guidelines in Chapters 2 and 3. This chapter is intended to guide a DOT practitioner in making key decisions, such as where BMPs are sited, how they are sized, and how they will be maintained, and provides preliminary design alternatives for consideration. Within this structure, there is another decision gate where fatal flaws need to be assessed to avoid unnecessary effort on a project that would eventually prove to be infeasible.

Chapter 5: Decision-Making Framework and Supplemental Guidance, proposes a structured decision process for evaluating alternatives, defining key data gaps, and scoping necessary studies to support the selection of a preferred alternative or a determination that no feasible alternatives are available. This is the final step that is within the scope of this research project and Guide.

Appendix: On-Bridge Stormwater Treatment Case Studies, includes project examples showing how on-bridge BMPs have been implemented or designed, as well as hypothetical examples of the preliminary design process applied to real bridges. These studies highlight the diversity of conditions and design approaches that may be encountered in the bridge environment.