On-Bridge Stormwater Treatment Practices: A Guide (2024)

Chapter: 3 Stormwater Treatment Practice Design Options

CHAPTER 3

Stormwater Treatment Practice Design Options

Chapter at a Glance

This chapter focuses on the design of the stormwater treatment practice (referred to as best management practice or BMP in this Guide). BMPs are a core part of an overall stormwater capture and treatment design. While adaptations will be needed for project-specific conditions and objectives, it is possible to standardize a menu of options for BMP design that can be adapted within a range of project-specific constraints. This chapter builds on the problem definition steps presented in Chapter 2. It presents the results of research to develop BMP design options and design parameters and presents a summary to guide the selection of a BMP design.

The purpose of this chapter is to guide a reader in answering the following questions:

- What potential treatment options can meet on-bridge stormwater treatment design objectives? How were these identified?

- How can a non-proprietary BMP be designed to meet design objectives within on-bridge constraints?

- What are the maintenance needs of the proposed BMP conceptual design?

- What role can proprietary products play in on-bridge treatment?

Summary of Research Process and Outcomes

This section provides a high-level overview of the research process and outcomes to develop a proposed BMP design concept. Details of the design development and associated research are provided in NCHRP Web-Only Document 401: Developing a Guide for On-Bridge Stormwater Treatment Practices. Table 2 provides a summary of the research steps and key outcomes.

The following sections provide additional information about the proposed filtration media and BMP design.

Review of Candidate Treatment Processes

Primary Finding

The research effort concluded that a high-rate media filtration system with blended reactive media would be the most viable potential treatment process for an on-bridge environment. This section provides a summary of the research that supported this finding.

Table 2. Summary of research process and primary outcomes.

| Research Step and Primary Activities | Key Outcomes and Rationales |

|---|---|

Treatment process selection

|

|

Candidate filtration media design

|

|

Candidate BMP design

|

|

Laboratory research of key variables

|

|

Sizing analysis

|

|

Case studies

|

|

Supporting Basis

For this study, copper and zinc were identified as the primary target pollutants, with phosphorus and 6PPD-quinone as additional focal pollutants. Stormwater characterization for metals is relatively complex and variable. On average, particulate-bound metals account for around two-thirds of metal mass in stormwater runoff, with metals usually binding to fine particulates. However, there is variability, and in addition to particulate-bound metals, there are also several different chemical species present in the dissolved fraction of stormwater, each with different bioavailability and removal mechanisms. The speciation can vary from site to site and from storm to storm. Additional information on this topic is available in prior NCHRP reports, including NCHRP Report 767: Measuring and Removing Dissolved Metals from Stormwater in Highly Urbanized Areas (Barrett et al. 2014). There are several treatment processes that can effectively remove metals from stormwater. There are also processes that can reduce the toxicity of metals without removing them from runoff. These processes include sedimentation or gravity separation, inert media filtration, sorption, and changes to metal speciation.

Some particle sizes can be separated by sedimentation with adequate settling time. However, due to space constraints, effective sedimentation for fine particulates is not compatible with treating runoff in the bridge deck environment, so sedimentation was not considered further. Hydrodynamic separation (HDS) may be more compatible with bridge deck space constraints. However, analysis of HDS systems in the International BMP Database (Clary et al. 2020) showed very little copper or zinc removal by these types of devices.

Permeable friction course (PFC) is a potential candidate for bridge decks that has been considered as part of previous research on bridge deck runoff (Taylor et al. 2014a). This could complement other treatments by reducing influent loads, which would extend the life of the filter media. However, the purpose of this project was specifically to review additional treatment mechanisms beyond PFC. Therefore, PFC was not considered further.

Smaller particle sizes are easily removed via filtration, which, depending on the filtration media type, can also provide the benefit of good treatment of dissolved pollutants. Therefore, sorptive media filtration is considered the most applicable approach for removing both particulate and dissolved copper and zinc from stormwater runoff in the bridge deck environment. This treatment process also has the potential to impart changes in speciation that can reduce toxicity without changing overall metal mass. Additionally, sorptive media filtration can provide co-benefits for other pollutants beyond copper and zinc, including other heavy metals, total suspended solids (TSS), toxic organic compounds (e.g., polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, 6PPD-quinone), hydrocarbons, whole effluent toxicity, and nutrients.

Sorptive media filtration can be broken into the following separate treatment mechanisms, with some overlap between the two:

- Inert media filtration consisting of cake (surface) filtration and depth filtration, whereby particles are removed primarily via physical mechanisms.

- Media sorption, whereby pollutants are primarily removed via chemical mechanisms.

To balance particulate removal with media bed lifespan, a media filtration system design that promotes depth filtration and straining is more likely to have a longer lifecycle than a design that promotes cake filtration.

Removal of dissolved metals requires some form of sorptive process, which can include ion exchange and/or adsorption. The relative role of each sorptive media component can vary depending on influent characteristics. A combination of media components providing different sorptive mechanisms appears to be desirable, as this provides a robust treatment system that should work across variable influent characteristics and changing seasonal conditions.

Selection of Candidate Media

The research team performed the following steps to select a candidate media blend for testing:

- Determine target media characteristics, including hydraulic properties, physical strength, and removal mechanisms.

- Review of performance data for five existing media blends that have been tested at field scale with real stormwater.

- Adaptation of most suitable existing media blends to materials that have broad nationwide availability and higher media flow rates.

- Testing of the selected media for permeability, clogging, and water quality performance.

These steps are further documented in NCHRP Web-Only Document 401: Developing a Guide for On-Bridge Stormwater Treatment Practices.

NCHRP 25-61 Filtration Media

Through the research process outlined earlier, a proposed filtration media blend was designed and tested. This section provides template material specifications, performance expectations, and key design criteria for the filtration media blend proposed by this project. It also provides guidelines on media blend adaptations that could be made while providing similar treatment performance.

Media Composition and Template Material Specifications

Based on the research, analysis, and prioritization presented earlier in this chapter, this report proposes a filtration media with approximately the following components and volumetric proportions (Table 3). The filtration media should be fully mixed prior to placement in the BMP.

The primary rationales for this blend’s design are:

- This media blend provides multiple treatment processes and has exhibited reliable performance consistent with TAPE enhanced and phosphorus standards in both field studies (up to 14 in/h) and in the laboratory (up to 50 in/h). It also provides high removal for 6PPD-quinone. This blend differs only slightly from what has been tested in both laboratory and field applications in Washington State. A similar blend has received TAPE certifications at 60 in/h (Washington Department of Ecology 2022). Performance is discussed later in this section.

- The media permeability is high, which is expected to provide resistance to clogging and support high filtration flow rates.

- The media blend is composed of materials that are readily available throughout the country.

- Each additive offers a complementary role: Granular activated carbon effectively removes metals in multiple forms and organic pollutants. Coconut coir pith augments the cation exchange capacity of the media. Activated alumina targets soluble phosphorus.

Table 3. Media component suggestions.

| Component | Fraction of media blend by volume |

|---|---|

| Coarse Washed Sand | 60% |

| Coconut Coir Pith | 20% |

| Granular Activated Carbon | 15% |

| Activated Alumina | 5% |

Figure 3. Media components (left to right): sand, coconut coir pith, activated alumina, granular activated carbon.

Template specifications for media components are provided in the remainder of this section. Figure 3 shows pictures of each product individually, based on the materials that were tested as part of this project. Figure 4 shows the blended media.

Washed Coarse Sand Specifications

Washed sand is the primary stormwater filtration media and provides structural support for other media. The particle size distribution of sand should be balanced to provide adequate permeability and resistance to clogging (e.g., a target starting permeability > 200 in/h) while being fine enough for effective particulate filtration. It is also important for the sand to have a similar range of grain sizes to other media components to avoid separation of components. For the prototype media blend, the research team selected and tested a poorly graded sand known as #20/30 sand, which is widely used in water filtration applications.

The particle size distribution of the sand should conform to those for a #20/30 filter sand, as presented in Table 4, or a similar grain size distribution specified by the project designer. Other sands with a predominant grain size between about 0.02 and 0.04 inches and very little material finer than the 50 sieve (0.01 in) would likely provide similar filtration properties. Sand should

Figure 4. Blended filtration media.

Table 4. Proposed particle size distribution requirements for sand media component.

| Sieve Number | Nominal Sieve Opening, inches | Minimum Percent Passing (% by mass) |

Maximum Percent Passing (% by mass) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 0.047 | 95% | 100% |

| 20 | 0.033 | 60% | 90% |

| 30 | 0.023 | 15% | 40% |

| 50 | 0.012 | 0% | 5% |

| 100 | 0.006 | 0% | 2% |

be comprised entirely of mineral aggregate derived from materials that have not been previously used for agricultural purposes to avoid the potential for nutrient leaching. The sand used in the laboratory testing was a silica sand.

Material Availability Assessment: A #20/30 sand is a common gradation used in aquarium filters and water treatment applications and is similar to gradations used in golf course bunkers. Due to these various uses, regional sources are likely available within reasonable proximity to most project sites. The sand used in testing was obtained from Lane Mountain Quarry in Stevens County, WA. Specialty sand typically costs around $100 per cubic yard or about $70 per ton.

Coconut Coir Pith

Coconut coir pith is a fibrous organic media derived from coconut husks and has characteristics similar to those of sphagnum peat. Coir provides some sorption capacity for metals and organic compounds that may be associated with copper and zinc. It degrades extremely slowly, so it is not expected to degrade within likely O&M cycles. Coconut coir pith should conform to the following requirements:

- Be free of stones, stumps, roots, or other similar objects larger than 5 millimeters.

- Be aged for a minimum of 6 months. Coir fibers from ripe coconut (Cocos nucifera) husk shall be freshwater-cured for at least 6 months.

- Be rinsed and washed during production with non-saline waters.

- Be screened to remove coarse fibers during production. Fibers should have an average length between 10 mm and 20 mm. Dust or particles smaller than 1 mm should be screened and removed prior to use in media blends.

- Be decompressed and rehydrated prior to blending.

- Comply with the following analytical limits:

- pH: 6.0–8.5

- Salinity: < 2.0 mmho/cm as electrical conductivity

- Total Carbon: > 35% on a dry weight basis

- Total Nitrogen: < 1.5% on a dry weight basis

- C:N Ratio: > 40

- Organic Fraction, dry weight: > 70%

- Testing of coco coir pith products by members of the research team in Washington and California suggests that these limits can consistently be met.

Material Availability Assessment: The material used in laboratory testing was Botanicare Cocogro (owned by ScottsMiracle-Gro, Inc.), a common, commercially available coconut coir pith. It can be purchased in bales from e-commerce sites. The raw material is sourced from

Sri Lanka and freshwater-processed in the United States. This product has been commonly used in alternative media blends in Washington State and California. It is also a common additive for potting soil in place of sphagnum peat. Coco coir pith typically costs less than $100 per cubic yard or about $200 per ton if expanded.

Granular Activated Carbon

Granular activated carbon (GAC) is a common product used for water treatment applications. GAC should be derived from coconut shell, bituminous coal, or a similar virgin product of a grade used for water treatment applications. Particle size should meet the following limits:

- No more than 5% larger than the #8 mesh (2.36 mm) and no more than 5% smaller than the #30 mesh (0.6 mm). In other words, more than 90% of the material should be between these mesh sizes.

- Coefficient of uniformity < 2.0.

- Total ash content <8% by weight.

GAC used for water treatment applications typically meets additional standards for abrasion, hardness, and density that are less important for stormwater treatment applications where filter backwashing does not occur.

Material Availability Assessment: The material used in laboratory testing is COL-L 60, 8 × 30, GAC procured from Carbon Activated Corp. Carbon Activated Corp has facilities in Texas, New York, Florida, Arizona, and Canada, as well as operations in other countries. Products can be shipped throughout the country. Other GAC supplies sell similar products. GAC typically ranges from $1,000 to $1,500 per cubic yard or about $2,500 to $3,500 per ton.

Activated Alumina

Activated alumina is a highly porous material derived from aluminum oxide. It is typically used in industrial applications. Activated alumina should conform to the requirements in Table 5.

Material Availability Assessment: The material used in laboratory testing is Axens Solutions ActiGuard AAFS50. This product is an iron-enhanced activated alumina. This product has been used in pilot media in Western Washington. Axens is a worldwide company that ships products throughout the country. Activated alumina can be sourced from several suppliers in the United States. Activated alumina typically ranges from $1,000 to $1,500 per cubic yard, or about $2,000 to $3,000 per ton, similar to the price range for GAC.

Estimated Cost of Blended Media

The raw material cost of the blended media is estimated to be approximately $350, plus shipping, blending, and material handling. A unit cost of about $500 per cubic yard (CY) is likely reasonable as a rough planning level estimate but will vary by location.

Table 5. Proposed specifications for activated alumina media component.

| Parameter | Range | Units | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum Oxide (Al2O3) Content | > 92 | % of total dry mass | Vendor analysis |

| Bulk Density | > 760 | kg/m3 | Vendor analysis |

| Particle Size Range | 0.5 - 2 | mm | ASTM D422 |

| Surface Area | > 300 | m2/g | Vendor analysis |

Shredded Wood Mulch Pre-treatment Layer

The researchers suggested a layer of shredded wood mulch on the surface of the media bed to serve as a pre-treatment layer. This configuration was not tested. This approach serves to protect the underlying media from clogging by providing a more highly textured surface. This also supports routine maintenance via raking and replacement of mulch. This approach is common in proprietary media filtration systems (summarized later in this Guide). The City of Bellingham (Washington Department of Ecology 2022) also recently completed testing of a similar media blend and treatment system, which included a 2-inch layer of mulch as the first phase of treatment. Summarizing from specifications provided by the City of Bellingham, mulch should be derived from ground wood. It should not be chipped material or bark dust. It should generally have particle sizes between 0.25 inch and 3 inches.

Results of Testing Performed on Selected Media Blend

Laboratory experiments were performed to confirm the hydraulic and water quality capabilities of the previously described custom media blend. Specifically, column studies were conducted to examine the relationship between solids loading and time to clog, as well as to determine the required depth of media and media filtration rate required to obtain representative water quality effluent characteristics.

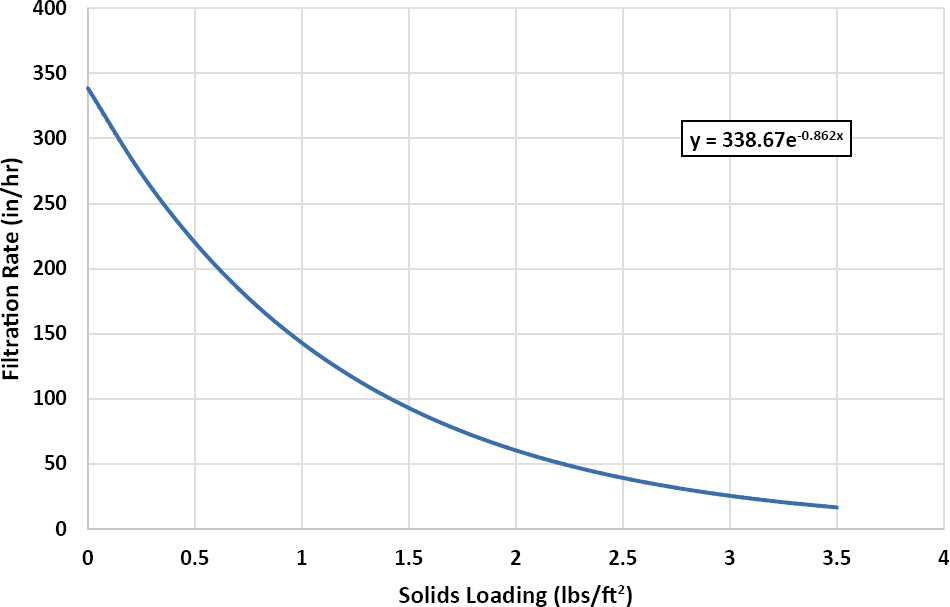

For the permeability and clogging tests, the experimental approach involved running a series of falling head, rigid wall hydraulic conductivity tests with sequential additions of stormwater solids. Changes in permeability with the addition of the solids were used to determine the relationship between solids loading and permeability. Because the source of solids used for these experiments was a hazardous material trap, the experiment did not account for colloidal-size particles or oil and grease. Consequently, the results of the study are considered to be an optimistic estimate of the load that a media bed can receive without clogging if not protected by mulch or another sacrificial layer. Results showed a load to clog of approximately 3.0 to 3.3 lb/ft2 at 25 in/h or 2.2 lb/ft2 at 50 in/h, which is similar to results reported in other literature. Figure 5

shows the measured decline in media filtration rate with increasing solids loading based on the testing done as part of this project.

For the water quality portion of the study, researchers employed a series of column experiments to evaluate the water quality treatment performance of the proposed non-proprietary media blend. The study evaluated pollutant removal performance in a system with a loading rate of 50 in/h and compared removal performance at this higher rate to removal performance at more typical loadings of 14 in/h. The study also took samples at three different media depths (6, 12, and 18 inches) to determine the required media depth to achieve effluent of the desired water quality.

The results of the laboratory testing confirmed the selected media is capable of removing dissolved copper and zinc to TAPE enhanced requirements under the conditions of high loading (up to about 50 in/h media filtration rate). This includes at least 30% removal of dissolved copper and 60% removal of dissolved zinc. The results also confirmed that 18 inches of media depth is necessary to consistently meet effluent water quality goals. The preponderance of data suggests the media has the capacity for dissolved zinc and copper removal for at least one year of runoff. There was some indication that performance will gradually decline over time.

With respect to phosphorus, high removal of dissolved phosphorus was observed at high concentrations (around 55% removal at influent concentrations of 0.2 mg/L). However, some leaching of dissolved phosphorus was observed when influent concentrations were low (added concentration of approximately 0.03 to 0.10 mg/L at an influent concentration of 0.044 mg/L). Overall, for typical highway runoff water quality, the media is expected to remove total phosphorus at a level reasonably consistent with TAPE phosphorus standards (50% removal of total phosphorus).

Due to the findings of recent research on the toxicity of 6PPD-quinone to some salmonids (Brinkmann et al. 2022; Tian et al. 2022), the removal of 6PPD was also studied, and the media was found to be quite effective. An effluent concentration of 11 ng/L was measured while running the experiment at 63 in/h (influent concentration approximately 250–530 ng/L), which is below the reported LC50 of 95 ng/L for coho salmon (Brinkmann et al. 2022; Tian et al. 2022).

Recently completed testing by the City of Bellingham, Washington, found a similar blend met TAPE phosphorus and TSS treatment standards at 60 in/h (Washington State Department of Ecology 2022). The City of Bellingham system includes a three-phase treatment system, including (1) pre-treatment with shredded mulch, (2) primary treatment with a mix of coarse clean sand (70% by volume), coco coir pith (20% by volume), and high carbon wood ash (similar to GAC, 10% by volume), and (3) a polishing filter consisting of sand (80% by volume), activated alumina (17% by volume), and iron filings (3% by volume). The sand specification is somewhat coarser than the proposed prototype blends, with most sand coarser than the 16 sieve. The initial permeability was about 190 in/h and was restricted to 60 in/h for treatment (Washington State Department of Ecology 2022).

Key Design Parameters for Applying Filtration Media within a BMP Design

Media Filtration Rate

Treatment performance of the selected media blend at 50 in/h meets TAPE benchmarks for dissolved copper and zinc and achieves high level of 6PPD-quinone removal. This supports a design media filtration rate of 50 in/h. Higher rates could be considered, but further increasing the design flow rate would reduce the media bed footprint, and it is likely that clogging would control the sizing of the media bed.

A media filtration rate of 50 in/h corresponds to a provided treatment with a flow rate of 0.00116 cfs (cubic feet per second) per sq ft or 0.51 gpm (gallons per minute) per sq ft.

This is consistent with findings from recently completed testing by the City of Bellingham, WA, on a similar media, which was approved for 60 inches per hour.

Media Bed Depth

For the selected media, data from interim sampling points showed considerable improvement in water quality with each increment of depth through the media bed. The full 18 inches of media depth was needed to consistently meet TAPE benchmarks. For example, testing showed approximately 60 percent removal of dissolved copper at 50 in/h for an 18-inch column but closer to 30 percent removal for a 12-inch column. If treatment system weight is a critical factor, substantial removal could be achieved with 12 inches of media. Testing shows that there would be compromises in treatment performance with a 12-inch media bed; however, if site-specific data is available, designers may be able to use the data to determine if the extra removal efficiency provided by 18 inches of media is needed to achieve treatment goals. In situations where vertical space availability is a critical design parameter, designers may also choose to use a lower design filtration rate and, therefore, a larger footprint to rectify the decreased treatment performance brought forth by the shallower media depth.

Loading to Initial Maintenance

Load to initial maintenance is a measure of the mass of suspended sediment that can pass through one unit surface area of the media filtration bed before the media filtration rate declines below the design rate. For the selected media, under the proposed media filtration rate of 50 in/h and assuming a system that includes a settling chamber for pre-treatment, the suggested load to clog for design purposes is 2.2 lb/sq ft. If the media is allowed to decline to 25 in/h, the allowable load to clog is 3.3 lb/sq ft.

Table 6 presents a comparison with previous clogging studies. What makes an accurate comparison difficult is that there is no standard testing protocol or agreement on what constitutes “clogged.” As one can see in the table below, the final value of permeability as a percent of the

Table 6. Comparison of solids loading for clogging.

| Study | Solids Loading, lbs/ft2 | % of Initial K at Conclusion | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| This Work | 3.3 2.2 |

8% 14% |

Clogged defined at 25 in/h and at 50 in/h |

| Kandra et al. (2014) | 1.2 – 4.3 | 5% | Varied depending on media characteristics |

| Barrett et al. (2013) | 2.5 | 16% | K relatively constant and columns not clogged |

|

Pitt and Clark (2010) Pitt and Colyar (2020) |

2 – 2.5 | 17% | Lab with field verification |

| Fairbaugh (2022) | 1.9 | NA | Water with TSS, organic matter, and motor oil (7 mg/L) |

| Poresky et al. (2019) | 1.9 | 25% | Clogged defined as 50 in/h |

initial value varies substantially. However, agreement between these studies is fairly strong, given the range of variables that can affect the clogging process.

The most similar study was conducted by Kandra et al. (2014), even though the solids used in their experiments contained substantially larger particles than in this study. They found that the rate of clogging varied somewhat by filtration media characteristics, but the dominant factor seemed to be the filtration rate, with the most rapid clogging associated with the highest flow rates.

Biofouling of media beds has been observed as a hydraulic failure mechanism, particularly where seasonal rainfall maintains continuously wet conditions (personal communication, Jim Lenhart). This study included accelerated aging and did not attempt to simulate the full loading conditions found in the highway environment. Therefore, the scope of this study did not support the evaluation of potential biofouling.

It should be noted that the influent to the columns did not include large debris, coarse solids, traction sand, floatable sheens of oil and grease, or other materials that can clog media beds. Pre-treatment via a settling chamber and downturned elbow for floatable material exclusion is typically effective in removing much of these components and reducing the variability of stormwater influent. The results should be applied to designs where pre-treatment is provided.

Media tested in this project was not protected by a layer of mulch that would tend to provide protection and confer a factor of safety on the values above.

Overall, we believe the findings of past studies are all relatively similar, and the findings of this study are generally comparable to previous studies. While there is significant uncertainty in the lifespan of media associated with variability in stormwater characteristics, loading rates, and other factors, the clogging tests performed as part of this study show that this media is similar to prior high-rate media tests with respect to its susceptibility to clogging.

Equivalent Design Adaptations

This research project sought to confirm the proposed media blend at the target flow rate. It did not individually explore the effect of each component or different mix proportions to identify an optimal or uniquely superior blend. It is likely that similar results could be achieved with these or similar media components. Where materials are not readily available locally, DOTs should exercise reasonable judgment to identify alternative source materials. The following guidelines apply to design adaptations:

- Particle size gradations are believed to be important for permeability and clogging. Therefore, particle size gradations should be reasonably similar to the specified ranges. However, minor changes in particle size are acceptable.

- Coco coir pith is contained in some blends to support plant growth. However, this is not a goal in the bridge environment. Therefore, this material could be removed from the mix and replaced with an alternative source of cation exchange capacity.

- Zeolite is a candidate substitute product for coco coir pith. If zeolite is used, it should be clinoptilolite zeolite with a particle size gradation similar to the specified sand. Zeolite was not tested as part of this project. However, zeolite has been used in a similar media blend with good results (Pitt and Clark 2010; Pitt and Colyar 2020).

- A layer of shredded mulch is commonly used on the surface of filtration BMPs to reduce clogging risk and enable simplified removal and replacement of materials on a routine maintenance cycle. This would have a limited effect on treatment performance and is proposed as part of BMP design.

NCHRP 25-61 Prototype BMP Design

This section is intended to guide a DOT practitioner in designing a project-specific BMP based on the prototype developed in this project. This section includes (1) a brief justification for the major design decisions made in developing the proposed prototype BMP design, (2) schematics and descriptions of the key elements and configurations of the prototype BMP, and (3) a discussion of the equivalent design adaptations that can be considered.

The BMP design is referred to as a “prototype” as it has not been actually assembled or field tested. However, the major features of this design (e.g., sump pre-treatment, media filtration, slotted well-screen underdrain, outlet orifice control) have been well-demonstrated in standard BMPs and have a reasonable basis for adaptation to this prototype. Additionally, as a prototype, this design is intended to illustrate the overall configuration of the BMP and enable DOT- and project-specific adaptation based on preferences and project needs.

Conceptual Design Decisions and Rationales

Table 7 summarizes the major conceptual design decisions used in the development of the prototype BMP described in this chapter.

Table 7. Key conceptual design decisions and rationales for prototype BMP design.

| Major Design Decision | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Utilize a simple vertical flow configuration. |

|

| Provide 6 inches of headspace over media. |

|

| Develop a modular design that can be tailored to a given flow rate by adjusting the number of units. |

|

| Utilize flexible and removable connections with conveyance systems and between modules. For conveyance, provide lifting lugs to enable the removal of full modules. |

|

| Incorporate a pre-treatment system that provides pre-settling and a downturned elbow or baffles for oil-water separation. |

|

| Major Design Decision | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Allocate pre-treatment volume of approximately half of the gross volume of the media bed. |

|

| Enable a single point of inflow to each series of treatment units. |

|

| Support media depths of 18 inches. |

|

| Design for full 50 in/h design filtration rate. |

|

| Use loose media in media beds rather than bags or cartridges. |

|

| Include a 2-inch layer of shredded hardwood mulch on the media surface. |

|

| Utilize slotted well-screen pipe embedded in media rather than perforated underdrain in gravel. |

|

| Incorporate a hydraulic control device such as a valve or orifice on underdrains. |

|

| Allow for freeze-thaw expansion of pretreatment sump by avoiding entrapping water. |

|

Prototype Design Schematics

Building on the key design decisions presented in Table 7, the research team developed two prototype BMP conceptual designs: one with a separate forebay module and one with an integrated forebay module. These designs meet most of the design objectives reasonably well. However, these prototypes are intended to be simple enough to be adapted by a design team to the specific needs of a project.

Figure 6 through Figure 8 show a system with an integrated pre-treatment compartment within each module, with Figure 6 showing a profile view of the system, Figure 7 showing an end view, and Figure 8 showing a plan view. Figure 9 shows an adaptation of this design with pre-treatment provided in a separate tank module. This assumes all flow will enter the pre-treatment module and then flow to the remaining filtration modules. The former alternative enables the treatment of smaller drainage areas. The latter alternative could be used where it is suitable to place a larger system treating a larger drainage area. Many other configuration options are possible.

The schematics in Figures 6 through 9 are not to scale. Alternative dimensions and configurations are possible. See the discussion in the “Equivalent Design Adaptations” section in this chapter.

The schematics in Figures 6 through 9 show an example attachment concept. However, this BMP prototype could be mounted anywhere that a horizontal structural rack is provided. Additional access ladders and platforms are not shown for simplicity but will likely be required.

Note that the schematics depicted in Figures 6, 7, 8, and 9 show an example of BMP placement within the bridge environment. However, guidance for placement of the BMP is not the subject of this section of the Guide. See Chapter 4 for guidelines on placement, including the ability to access BMPs for inspection and maintenance.

Equivalent Design Adaptations

As discussed earlier, the prototype design is intended to be adapted to specific project conditions and design team preferences. The following adaptations should have limited effect on performance and O&M:

- Use of alternative horizontal dimensions.

- Use of proprietary media blends that have TAPE Enhanced and Phosphorus General Use Level Designation (GULD) certifications in place of the non-proprietary media described in this chapter (see additional information on proprietary options in “Proprietary Stormwater Treatment Options” in this chapter).

- Use of various materials for the treatment box, including fiberglass, plastic, non-corrosive metal, or other products that do not leach contaminants and meet structural needs.

- Adaptation of pre-treatment dimensions to ensure that a vacuum truck can fit between baffles.

Weight Estimates

Weight estimates depend on the dimensions of the BMP and the materials used. The weight of stormwater treatment systems is a key input to structural analyses and to determining necessary specifications of O&M equipment (e.g., lifting capacity).

The design weight of a BMP should consider both the original design features and the accumulation of water and sediment that may occur at the end of a maintenance cycle. Since sediment load can be highly variable between locations, it is appropriate to assume that the system has completely filled with sediment between maintenance events. When estimating the added weight, the design team should consider the following components:

- Conveyance elements such as pipes and gutters. Assume that conveyance systems are filled with saturated sediment and debris. More information on conveyance systems is provided in Chapter 4.

- Stormwater treatment device and mounting apparatus. Assume that the pre-treatment and headspace of the media is filled with sediment and the pore space of the entire system is saturated.

- Weight of maintenance personnel. Assume that three people will be supported by the treatment system during manual maintenance activities.

For an example unit with dimensions of 4 ft × 6 ft, the total weight would be calculated as follows:

- Stormwater treatment BMP: 7,100 lbs (5,000 lbs at the start of the maintenance cycle, 7,100 lbs at the end of the maintenance cycle)

- Saturated media at 130 lbs/cu ft: 3,000 lbs

- Sump filled with water at 62.4 lbs/cu ft: 1,000 lbs

- Allocation for box: 1,000 lbs

- Additional weight from sediment accumulated in both the sump and treatment media: 2,100 lbs

- Allocation for mounting hardware and frame: 2,000 lbs (to be detailed based on structural analysis)

- Allocation for three maintenance workers: 750 lbs

-

Example conveyance system: 4,700 lbs, distributed over 100-ft span of bridge

- Assume 100 feet of 6″ diameter cast iron piping (22 lbs/ft): 2,200 lbs

- Saturated sediment filling piping at a unit weight of 130 lbs/ft3: 2,500 lbs

In this hypothetical case, each unit of this size would add approximately 14,700 lbs of load. Approximately 10,000 lbs of this load would be at the point of attachment, and approximately 4,700 lbs would be distributed over the 100 ft span of the collection system.

These hypothetical estimates are intended as an example only. Design teams should consider the proposed project-specific design of conveyance, mounting, and stormwater treatment systems when estimating weights for structural analysis.

O&M Requirements

For the design described in this section, the BMP and conveyance system are anticipated to have additional O&M needs compared to routine maintenance of on-bridge drainage systems. These additional O&M needs are described in Table 8.

Proprietary Stormwater Treatment Options

Overview

Space constraints are common in stormwater management applications. Adapting to these constraints has contributed to more than two decades of research and development of proprietary treatment technologies that are adapted to provide effective treatment with a small footprint.

Several proprietary high-rate media filtration technologies have been approved to meet “enhanced” and “phosphorus” treatment criteria at the GULD under TAPE at rates of between 96 and 175 inches per hour. Current media filtration products with GULD for enhanced treatment include:

- Filterra® Bioretention

- Modular Wetlands® Linear Bioretention System for Stormwater

- BioPod® Biofilter (with a box or as loose media)

- StormTree® Tree Filters

- Stormwater Management StormFilter®

- Jellyfish Filter®

These systems have field-scale, third-party testing to meet TAPE enhanced goals. StormFilter® cartridge media filtration systems with Phosphosorb Media have GULD approval for phosphorus treatment and basic treatment. Several other products have similar certifications.

There are two potential uses of proprietary technology for on-bridge treatment:

- Procurement of proprietary filter media from certified technologies to be used in the prototype BMP configuration described in the previous section.

- Procurement of full packaged system, potentially with customer manufacturer adaptations for the bridge environment.

The purpose of this section is to provide an overview of product availability and potential options for a performance-based specification that could be met by multiple vendors. This Guide makes no product recommendations.

Note: NCHRP does not endorse proprietary products. The information on proprietary products presented in this section is intended to serve as a neutral, technically based summary of this class of technologies. This section does not represent an endorsement of specific products or an endorsement of proprietary BMP products in general.

Table 8. Estimated O&M requirements of prototype BMP in addition to routine maintenance of on-bridge drainage systems.

| Activity | Frequency | Equipment or Materials |

|---|---|---|

| Remove accumulated material from the pretreatment unit. |

|

|

| Scrape mulch (if used) or scrape the surface of the media. Replace with like material. |

|

|

| Inspect and tighten fittings as needed. |

|

|

| Clean added collection system elements (pipes, gutter drains). |

|

|

| Detach inflow pipe and reroute water around BMP when jetting drainage system. |

|

|

| Remove full-depth media and replace with new media. |

|

|

| Dispose of spent mulch and media, including waste characterization testing. |

|

|

*This study did not quantify the total life of media. It is likely that clogging will progress to a point where full-depth remediation of media is needed prior to exhausting media treatment capacity. However, with effective pre-treatment, surficial mulch, and regular mulch removal, the intervals for full-depth media replacement can be increased.

Summary of Selected Proprietary Systems

Table 9 summarizes basic attributes of several vendor-provided solutions and summarizes the prototype BMP described in this Guide as a point of comparison.

Table 10 presents technical specification information provided by vendor representatives. This information should be reviewed with the following caveats:

- The research team has not independently evaluated performance claims or price estimates.

- Weights are for standard precast units, which are typically buried. Systems suspended from a bridge deck may need to be substantially reinforced as compared to standard designs.

Table 9. Summary of basic attributes of selected proprietary BMP options.

| Treatment Product | Pre-Treatment Technology | Treatment Technology | Routine O&M | TAPE Approvals and Associated Loading Rates1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Filterra® Bioretention www.conteches.com/ |

Sacrificial mulch layer on surface. | High-rate blended filter media; downward flow. | Mulch removal and replacement. | 175 in/h for Basic and Dissolved Metals Treatment 100 in/h for Phosphorus Treatment. |

|

BioPod® Biofilter System https://oldcastleinfrastructure.com/%20brands/biopod |

Sacrificial mulch layer on surface. | High-rate blended filter media; downward flow. | Mulch removal and replacement. | 154 in/h for Basic, Enhanced, and Phosphorus. |

|

StormTree® Tree Filters www.storm-tree.com |

Sacrificial mulch layer on surface. | High-rate blended filter media; downward flow. | Mulch removal and replacement. | 120 in/h for Basic, Enhanced, and Phosphorus. |

|

Modular Wetlands® https://www.conteches.com/stormwatermanagement/biofiltration-solutions/modular-wetlands-linear/ |

Settling chamber and pretreatment media. | High-rate blended filter media; radial horizontal flow. | Vacuum pretreatment chamber; replace pretreatment media cartridge. | 100 in/h for Basic, Enhanced, and Phosphorus Treatment. |

|

Stormwater Management StormFilter® www.conteches.com/StormFilter |

Settling in vault bottom. | Syphon-activated, radial horizontal flow through cartridges. | Cartridge replacement. | 165 in/h for Basic and Phosphorus Treatment. |

|

Jellyfish Filter® www.conteches.com/stormwater-management/filtration/jellyfish-filter/ |

Settling in vault bottom. | Membrane filtration. | Membrane rinsing and periodic replacement. | 0.21 gpm/sf for hi-flow cartridges and 0.11 gpm/sf for draindown cartridges for Basic and Phosphorus Treatment. |

| NCHRP 25-61 Prototype BMP (for comparison) | Settling and oil separation in pre-treatment chamber. Sacrificial mulch layer on media surface. | High-rate blended filter media; downward flow. | Mulch removal. Potential surface scraping. | No TAPE approval. Lab testing showed performance similar to TAPE Enhanced and Phosphorus Treatment at 50 in/h. |

1Washington State Department of Ecology (n.d.) “Emerging stormwater treatment technologies. (TAPE)” https://ecology.wa.gov/Regulations-Permits/Guidance-technical-assistance/Stormwaterpermittee-guidance-resources/Emerging-stormwater-treatment-technologies#tape

2Price ranges are for reference purposes and may vary by location. Unless specified, prices do not include delivery.

Table 10. Summary of technical specifications of selected proprietary BMP options.

| Treatment product | Smallest model | Dimensions of smallest model (LxWxH) (inside dimensions) | Treatment flow rate of smallest model (cfs) | Gross weight of smallest model with media/cartridges1 | Approximate price range (2024)2 | Can products be supplied with custom box material? (e.g., metal, reinforced plastic) | Are treatment components available without the box? (e.g., to be installed in a customer-provided box) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Filterra® www.conteches.com/Filterra |

FT0404 | 4'x4' | 0.065 cfs (Basic and Enhanced) 0.037 cfs (Phosphorus) | Standard 3.5' tall unit ~ 10,000 lbs w/media. Media weight is 2,700 lbs/cy. | $17,000 - $22,000, depending on the configuration of the 4'x4' system. | Contech will consider custom designs if the job has adequate quantity. | Filterra Bioscape includes mulch, media, underdrain (pipe and stone), activation supervision, and Final Site Assessment. Available for larger quantities. Orders over 20 cu yd will be considered. |

|

BioPod® Biofilter System https://oldcastleinfrastructure.com/brands/biopod/ |

BPU-44IB | 4'x4'x4'6" | 0.029 cfs (Basic, Enhanced, and Phosphorus) | ~ 10,000 lbs w/media. Media weight is 2,100 lbs total. | $20,000, delivered to job site (cost based on 4'x4'x4'6" unit). | Not determined. | Replacement media available in super sacks for about $900/CY. Boxless Biopod includes all components (mulch, media, underdrain, drain rock, orifice) minus box available for $150 to $250/sq ft depending on size. |

|

StormTree® Tree Filters https://www.storm-tree.com/ |

4'x6' | ~4'x6'x3' | 0.067 cfs (Basic, Enhanced, and Phosphorus) | 14,000 lbs. | $15,000. | Not determined. | Yes, loose media is available for $180 to $300, depending on region, excluding delivery. |

|

Modular Wetlands® www.conteches.com/ModularWetlands |

MWS-L-4-4-V | 4'x4' | 0.052 cfs | Standard 4' tall unit ~9,900 lbs. Media weight is 1,600 lbs/cy. | $19,000-26,000. | A fiberglass box option has been provided in the past. Contech will consider custom designs if the job has adequate quantity. | Systems may be available as a kit, including media, underdrain, flow conveyance, and control structures. |

|

Stormwater Management StormFilter® www.conteches.com/StormFilter |

SFMH48 Catch basin | 4' manhole with 6' inside height (3 cartridges). Catch basin with 1-4 cartridges. | For three cartridges: 0.055 cfs with 12" cartridges 0.085 cfs with 18" cartridges 0.12 cfs with 27" cartridges | ~10,000 lbs. Phosphosorb cartridge weight varies from 55 to 80 pounds, depending on height. | $18,650-$24,350. | A metal inlet box option has been provided in the past. Contech will consider custom designs if the job has adequate quantity. | Systems may be available as a kit, including media, underdrain, flow conveyance, and control structures. |

|

Jellyfish Filter® www.conteches.com/Jellyfish Filter |

JF4 JFSI0404 - integrated surface inlet | Manhole: 4' manhole x 7'6" to 10'9" Inlet: 4'x4'x6'7" to 9'10" | 0.12 cfs with 15" cartridges 0.45 cfs with 54" cartridges | ~15,000 lbs at 10'9". Dry JF cartridges range from 6 to 22 lbs. | $29,000-$37,200. | Contech will consider a custom design if the job has adequate quantity. | Systems may be available as a kit, including media, underdrain, flow conveyance, and control structures. |

| NCHRP 25-61 Prototype BMP (for comparison) | NA | 4'x6' with 4'x2' pre-treatment and 4'x4' media bed. | 0.018 cfs | Approximately 5,000 lbs for treatment unit at the start of the maintenance cycle. (comparable to estimates described earlier). | Would be determined through bid process. | Yes, design is based on a custom box. | NA |

1Washington State Department of Ecology (n.d.) “Emerging stormwater treatment technologies. (TAPE)” https://ecology.wa.gov/Regulations-Permits/Guidance-technical-assistance/Stormwater-permittee-guidance-resources/Emerging-stormwater-treatment-technologies#tape

2Price ranges are for reference purposes and may vary by location. Unless specified, prices do not include delivery.

- Some vendors have experience providing systems in custom boxes, such as fiberglass or metal boxes, but this is not a standard offering.

- Weights do not include accumulated pollutants or water volume that may be expected during normal operation.

- Larger systems may benefit from significant economies of scale with substantially lower costs per flow-rate treated.

Table 10 also presents similar information for the prototype BMP described in this Guide as a point of comparison.

As shown in Table 9 and Table 10, there is a relatively wide range of vendor-supplied technologies that offer third-party verified treatment within a relatively small footprint. In comparison to the prototype BMP, several observations and comparisons can be made:

- These products are conventionally installed in the ground, so the design has not been optimized for weight or material strength in a free-standing application. Additionally, concrete boxes may be prone to freeze-thaw impacts if placed above ground in cold climates. Therefore, an adjusted design may be needed in many cases.

- When constructed in a concrete box, the weight of vendor-supplied BMPs is generally about 2× greater than the prototype BMP. Weights are all based on the BMP with media but without framing, piping, or sediment accumulation.

- These vendor-supplied systems offer higher flow rates, offering greater treatment rates per surface area of media. Some systems include patented flow configurations such as radial flow to maximize flow rate. For example, the 4′ × 4′ Modular Wetlands® provides a treatment flow rate of 0.052 cfs in a 16-sq ft footprint. In comparison, at a design media flow rate of 50 in/h, the prototype BMP would provide 0.018 cfs of treatment flow rate in a 4′ × 6′ footprint.

- Combining the two observations above, the treatment flow rate per weight is similar when proprietary products are provided in a conventional concrete box. For example, Modular Wetlands® in a standard concrete box has an approximately 3× greater flow rate but weighs approximately 2× more than the proprietary BMP.

Based on these observations, a weight-optimized solution could be achieved when a vendor-supplied BMP is provided in a custom fiberglass or plastic box or if a high-rate proprietary media is provided in the prototype BMP box. These options could potentially provide approximately 3× higher flow rate per unit of weight than the prototype BMP with the proposed non-proprietary media.

Some vendors offer O&M services. All vendors offer replacement media and components. Standard O&M frequencies are not uniformly reported and may vary substantially based on site-specific conditions.

Table 11 summarizes the pros and cons of proprietary products for bridge deck stormwater treatment applications.

Options for Performance-Based Specifications Inclusive of Proprietary BMPs

As summarized earlier in this chapter, there are some compelling reasons to consider proprietary technologies for an on-bridge design. However, incorporating proprietary designs into a design can be challenging without sole-sourcing a specific product. One option is to develop performance-based specifications that can include proprietary BMPs, enabling contractors to choose between a non-proprietary solution or a proprietary solution to meet the performance requirement.

Table 11. Summary of advantages and disadvantages of proprietary BMPs for on-bridge stormwater treatment.

| Primary Advantages | Primary Disadvantages |

|---|---|

|

|

Proprietary Filter Media in Contractor-Supplied Box

In this option, the design and specifications of the treatment box would be consistent with typical DOT design and procurement procedures for custom-designed elements. However, in specifying the filter media to be placed in the box, an option can be provided to procure a proprietary filter media product meeting performance specification.

This could be achieved by defining the baseline specifications for the non-proprietary filter media (as discussed above) and then allowing substitution with an alternate vendor-supplied product meeting the following criteria:

- Unit dry weight less than 100 lb/cu ft dry weight.

- GULD for Enhanced Treatment (dissolved metals) and Phosphorus Treatment at an approved flow rate of at least 50 in/h, or whatever design flow rate is used to size the BMP.

- [Optional] Supplied with necessary proprietary peripheral materials, including compatible mulch, underdrain pipe, and other applicable materials.

- [Optional] Installation observed by manufacturer representative.

If the design team chooses to design the system using a flow rate higher than 50 in/h, then a baseline non-proprietary option could be excluded from the specification, and the specification could call only for a vendor-supplied option meeting the criteria above. Multiple proprietary filter media products have applicable TAPE certifications of 100 in/h or higher.

Packaged System

In this option, the design team would allow flexibility for the entire treatment BMP to be supplied by a product vendor. This would mean that the stormwater capture and conveyance system, supporting structural frame, and maintenance access elements follow conventional design and procurement approaches, but the specific treatment device is not detailed. Rather, a set of performance specifications can be developed that enable multiple equivalent options to be used. These performance specifications would need to define the following:

- Minimum treatment flow rate that must be provided.

- GULD for Enhanced Treatment (dissolved metals) and Phosphorus Treatment at the design flow rate.

- Maximum length, width, and height.

- Maximum weight at the end of the maintenance cycle, assuming full sediment accumulation and media saturation.

- Size and location of incoming pipe penetrations and downstream pipe connections.

- Structural strength of box and ability to be self-supporting when installed on a frame.

- Lifting lugs adequate to lift the system when fully loaded with sediment.

- Minimum required O&M frequency.

- Provisions regarding acceptable materials, such as those driven by cold climate considerations or marine environments.

If these provisions are crafted for the specific BMP locations of interest, then they should be permissive of either the non-proprietary prototype BMP design or a vendor-suppled proprietary BMP. Weight limits could require vendors to supply customized systems with lightweight or reinforced boxes.