Structural Racism and Inequity in the U.S. Aviation Industry: Foundations and Implications (2024)

Chapter: 2 Group-Based Othering

2. GROUP-BASED OTHERING

LEARNING GOALS

This chapter includes three subsections that explain the process of othering, the social constructs that shape the process of othering, and the legacies of group-based othering within aviation.

- Understand the process of othering.

- Recognize how othering is the basis from which processes of racialization emerge.

- Compare present-day othering examples within aviation that involve social markers such as religion, gender, age, disability, and race.

INSIGHT WARM-UP

Historical Context

Philosophical writings helped shape today’s understanding of how self-identity is formed and how social systems produce ideologies of inferiority and superiority. What do you think influences the formation and hierarchies of social groups?

White supremacy is a system of exploitation and oppression that is significant in American history and contemporary American society. The Naturalization Act of 1790 is an early and explicit example of national policy that required immigrants to be “free white persons” of “good character”. What examples of white supremacy are you familiar with?

![]()

Lenses and Ways of Knowing

Scientists broadly understand that racialization is a social process and that racial categories are not an inherent biological identity. Social scientists widely acknowledge that experiences are intersectional and involve interlocking systems of oppression that target socially assigned combinations of identities. Lived experiences are not static, binary, or monolithic across groups.

Present-Day Legacies in Aviation

What do you know about the experiences of airport passengers, airport workers, and airport-adjacent community members with othered identity markers? How could the airport environment support persons with disabilities, persons who speak languages other English, and persons who identify as transgender? Airport passengers and airport workers may interact with facilities that do not meet their basic needs nor offer a dignified travel experience. How do you think the larger social process of othering may have affected the design of the airport? How can services and facilities be improved?

2. GROUP-BASED OTHERING

To understand the origins of inequities in aviation, it is necessary to first ascertain that those who are most negatively impacted by such inequities are those who have been “othered” through aviation planning and policymaking. Scholars credit philosopher Simone De Beauvoir (1949) with the introduction of “the other” as a social construct (Scarth 2004; Brons 2015). The literature has continued to expand in a range of scientific fields, developing further concepts of the other, othering, and otherness (Canales 2000; Brons 2015). A foundational knowledge on the construction of otherness is critical to understand the ways in which individuals in a society categorize themselves and inadvertently categorize others. Edward Said (1978) succinctly put forth that “othering is the invention of difference (an ‘Us versus Them’) to separate a dominant culture or group from a supposedly inferior other” (Said 1978).

In philosopher G.W.F. Hegel’s Master-Slave Dialect (1802) (a critical scholarly text discussing the other), Hegel argues that there is both a psychological dimension and historical dimension to self-identification. Reflecting on the Master-Slave Dialect, philosophy professor Lajos Brons writes that “in its encounter with the other, self-consciousness sees that other as both self and not-self” (Brons, 2015). Alternatively stated, the individual does not see the other as an essential being during the process of othering. Rather, the individual observes the other to define their own self-identity, which includes a process of defining the not-self (the non-essential, exclusionary, negative other). This results in a conceptual distance between what is socially and individually understood as the “self” and what is socially and individually understood as the other. In feminist and post-colonial literature, scholars refer to the process of creating distance between the notion of self and the notion of the other as the process of othering (McLaren 1992; Brons 2015).

The notion of othering is a foundational factor in the ways an individual understands and/or experiences race within society. Throughout history, the process of othering has resulted in the racialization of people based on physical attributes (Barot and Bird 2001). Racialization as a means of othering resulted in beneficial outcomes for those categorized as white at the expense of those who are not categorized as white (Barot and Bird 2001). In fact, inequities as a result of othering begin with racialization (Gans 2017). Developing an understanding of the extent of harm derived from othering based on race will allow insight into other forms of othering. For example, othering focused on identity markers such as religion, gender, age, and ability.

2.1 Process of Othering

The process of othering happens as identities become socially constructed, whereby individuals are marked, sorted, and grouped based on physical and cultural differences that do not fit into widely accepted social norms (in the U.S. context, normal is usually defined as being heterosexual, White, male, Christian). Harm from othering occurs when social and cultural differences are imposed and then used to establish and reinforce systems of oppression. One of the earliest and most apparent categories of marking is skin color (Canales 2000; Krumer-Nevo and Sidi 2012). Social scientists have noted that darker skin has historically been a pervasive determinant of othering. In the United States, “darker skin” is, for the most part, synonymous with being identified as “Black” (the darkest among the spectrum of skin tones) (Jablonski 2021; Eberhardt 2005; Franklin 1969). In addition to darker skin, physical attributes such as hair, facial structure, and body type are also makers that are used to assign Black, as an identity. Historical analysis demonstrates that the understanding of Blackness, and race in general, as a cultural and (later) racial identity, is a socially constructed identity.

The tactic of othering has evolved over time to mark additional variations in skin color (which mainstream discourse in the United States generally refers to as races) and has expanded to mark additional types of differences like disability, gender, dialect, and economic status (Krumer-Nevo and Sidi 2012). This understanding of how the process of othering has evolved over time can be framed as oppression’s origin story–whereby anti-Blackness is so deeply rooted that all other forms of oppression reproduce the tactics and outcomes associated with it (Stoneman and Packer 2020).

2.1.1 Process of Racialization

Racialization is described in the literature as being a process that happens to people as opposed to a biological identity that people are born with (Gonzalez-Sobrino and Goss 2021). Conceptually, racialization describes how people experience the racial identities that were assigned to them at birth, with the acknowledgment that different social contexts produce different racialization processes and outcomes. Social scientists call this a process of social construction (Gonzalez-Sobrino and Goss 2021). It is necessary for airport leaders to understand the relevance of racialization as a process when developing policy and programmatic interventions. Without this understanding, it is unlikely that proposed interventions will be sufficiently responsive to opportunities to fill equity gaps or redress longstanding, systemic oppression.

The concept of racialization, or racialization theory, emerged alongside debates about the validity of the concepts of biological race and social race. In the 1960s, the theoretical defining of racialization led to a study whereby medical scientists found “that there is more genetic variation within a group socially designated as a race than between so-called groups socially identified as different races,” and “race is not a scientifically reliable measure of human genetic variation” (Ifekwunigwe et al. 2017). To engage with the concept of racialization, one rejects the concept of a biological race (since there is no clear biological evidence to support its existence) and rejects the concept of a social race (since it can perpetuate misunderstandings that a biological race exists), instead deferring to the concept of racialized groups.

“But how should race be defined? Is it a biological or a social concept, for instance? Racial formation theory stipulates that “race” is both biological and social. The biological side is taken to be an illusion, while the social side is taken to be real. However, if “race” is not a biological or a social kind…then the idea of racial formation is misleading. The concept of racialization offers an alternative. By making a distinction between “race” and “racialized group,” the racialization theorist is able to offer separate terms for what is claimed to be real and what is claimed to be an illusion. “Race” can be understood as a biological category, which fails to refer to anything in the world. Racialized groups, on the other hand, are those groups that have been misunderstood to be biological races, and they are very much real.” (Hochman, 2019)

The process of racialization has been widely studied and critiqued. Amid critique of the racialization theory within the racial scholarship community, social scientist Adam Hochman (2019) argued in support of the theory, “racialization is not well understood as the process through which a group is labeled as a race. It is better understood as the process through which a group is understood to constitute a race”

(Hochman 2019). Hochman’s argument supports theoretical grounding that purported, “[racialization is] the processes by which racial meanings are attached to particular issues – often treated as social problems – and [the way] race appears to be the, or often [is, the] key factor in the way [race is] defined and understood” (Murji and Solomos 2005).

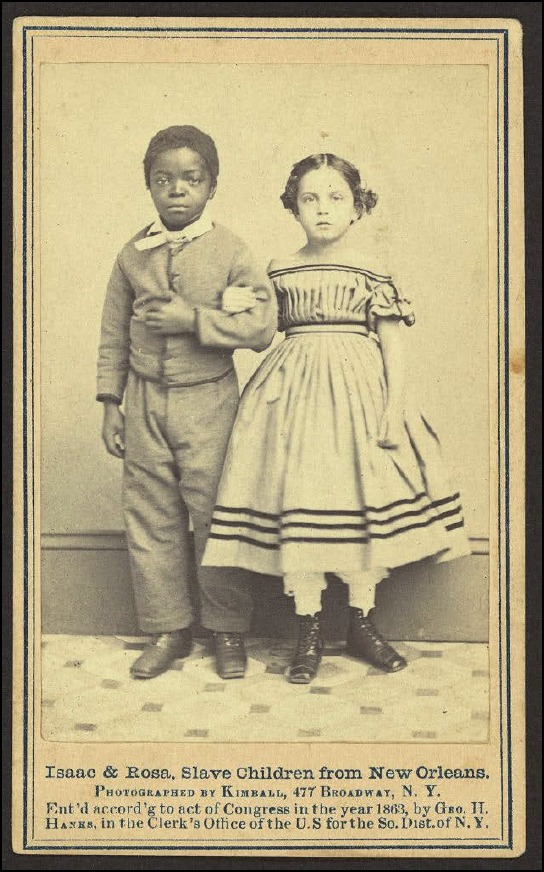

Figure 3 displays a photograph of a full-length portrait of dark-skinned Isaac White and light-skinned Rosina Downs, standing arm-in-arm, facing front. Both children were racialized as Black and were formally enslaved in New Orleans. Abolitionists distributed this photograph to raise money to educate emancipated children and to challenge the viewers perceptions of who is Black. The deliberate juxtaposition of the children’s skin tones also served to galvanize White northerners, some of whom feared that White people could be enslaved. The text on the back of the photograph reads: “The nett [sic] proceeds from the sale of these photographs will be devoted exclusively to the education of colored people in the Department of the Gulf, now under the command of Major-General-Banks.”

Source: Photograph taken by M.H. Kimball circa 1863 in New York, Library of Congress, Public Domain, https://www.loc.gov/item/2010647842/

Racialization (and race) can be challenging to navigate conceptually, particularly because of a common tendency to see race in binary terms: Black and White. Bianca Gonzalez-Sobrino and Devon R. Goss offer a three-part cohesive framing of racialization as both a process and a crisis.

“Race is a social construct and a historical artifact, which when conceptualized, is not a scientifically reliable measure of human genetic variation;”…“Race is also a political tool, a lived social reality, a self-ascribed identity marker, and a dynamic ideology that has an impact as institutional, structural and cultural racism;”…“Conceptions of race are informed by and inform biology, such as the deployment by society of phenotypic markers to differentiate and classify socially defined races or the embodied existence of health disparities among socially defined races.” (Gonzalez-Sobrino and Goss 2021)

The representation of race and racialization matters in contemporary media, including in discussions regarding inequity, which are becoming more commonplace and more contentious (Mihailidis et al. 2021). Specifically, there are concerns about whether media (and institutions more broadly) are meaningfully engaging in equity discourse. For example, some scholars have been critical of institutional efforts to tackle the subject of racial equity because institutional discourse often fails to acknowledge historical facts, which then severely limits opportunities for accountability. Particularly on the matter of race, crucial conversations about equity can be derailed when equity discourse is characterized as being a threat to “American heritage” (Carter and King-Meadows 2019). Such characterizations have become so prevalent that the body of literature describing the dynamic has coalesced around the term replacement theory (Raspail 1975; Chavez 2021). Replacement theory asserts that racialized people and immigrants are an ever-expanding populous that is consuming economic opportunities that would otherwise go to white people in the United States (Bellovary, Armenta, and Reyna 2020). This is further associated with the sentiment that White people are “falling behind” while immigrants and racial minorities are “pulling ahead”.

There is a vast body of equity-related scholarship, particularly scholarship focused on the processes of racialization. Racialized experiences are informed by systemic and social responses to the identity markers that individuals carry. The ways in which identity markers come to be and are defined are inconsistent and unreliable in terms of factual, measurable realities; yet those identity markers create dominant ideals that inform how society, institutions, and communities are constructed and governed. Racial categories, in many ways, define how one experiences every aspect of their life (Blascovich et al. 1997).

2.1.2 Racialization, Harm, and White Supremacy

The process of racialization has been reproduced and extended by relentless reinforcement of the notion of whiteness as an ideal state of personhood throughout American history. In The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: Racialized Social Democracy and the “White” Problem, scholar George Lipsitz (1995) credits the persistence of whiteness throughout time to cultural practices and political alliances that have shaped white supremacist constructions of the American identity (Lipsitz 1995). The construction of an American identity rooted in whiteness has left a “powerful legacy with enduring effects on the racialization of experience, opportunities, and rewards” (Lipsitz 1995). Scholar George

Lipsitz argues that after slavery ended, covert instances of systemic racism allowed for opportunities that prolonged the “possessive investment of whiteness” and maintained control over racialized people. Lipsitz argues that despite the mass mobilizations against racism as seen in the Civil rights Movement, the “scope” of white supremacy pivoted to counter these forces. Over time a renewal of racism occurs that changes the form of whiteness and white supremacy within the United States. He states, “Whiteness is everywhere in American culture, but it is very hard to see” (Lipsitz, 1995).

White supremacy constructs the notions of othering that inform the experiences of all people whose identities do not align with the normative paradigm that undergirds white supremacy culture (Essed et al. 2018). In I Am Not Your Negro, James Baldwin asserted, “The world is not white. It can’t be. Whiteness is just a metaphor for power” (Peck, Peck, and Strauss 2017). White supremacy is a “system of exploitation and oppression” that maintains power over racialized people by leveraging processes of othering to establish a false sense of homogeneity which purports there are two classes of humanity–white, and everyone else (M. Morris 2016). At the time that aviation technology was first developed, transportation services in the United States practiced overt discrimination and segregation, privileging passengers perceived as White.

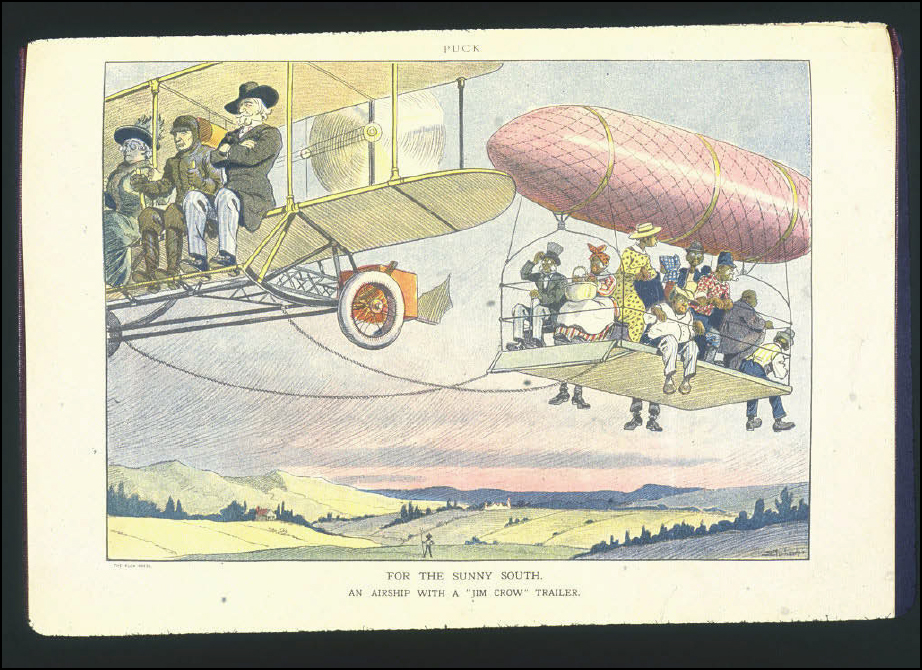

Figure 4 shows an 11 by 14-inch color political cartoon titled For the Sunny South. An Airship with a “Jim Crow” Trailer, which was published in the satirical magazine, Puck, in 1913. As described by Patti Williams at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, this cartoon “depicts an airplane with three well-dressed white passengers towing a “Jim Crow trailer,” crowded with African American passengers which is held aloft by a blimp. The caption was lampooning Jim Crow laws by satirizing the cramped conditions of Jim Crow railroad cars” (P. Williams 2022).

Source: Library of Congress, Public Domain, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2002720354/

Processes of racialization both derive from and reproduce white supremacy culture. While contemporary depictions of white supremacy reduce its ideals to the actions of supremacist hate groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, one of the most notable accounts of the origins of white supremacy points to the historic and ongoing imposition of Eurocentrism and European power, governance structures, and social ideologies around the world (Goldstein 2018). The global expansion of European forces beginning in the 16th century was a violent “conquest, colonization and universal legitimacy of European—and racialized white—power” (Trouillot 2003). An investigation into the meaning and applications of the term white supremacy is one that questions: who is a white supremacist, how does white supremacy manifest, what are the impacts of white supremacy, and who benefits most from white supremacy?

Such inquiries reveal that, as an ideology, white supremacy is a global dynamic that, historically, was intended to preserve many systems of control, including capitalism, meritocracy, monarchy, and exclusion. “White supremacy does not work alone; it is the modality through which many social and political relationships are lived” (S. Hall 1980). To know white supremacy is to know all forms of oppression and discrimination. Today, the cultural force of white supremacy relies on stereotypes (Bonilla-Silva 2001), protection of status quo (E. Wilson 2018), microaggressions (Huber and Solorzano 2020), intimidation tactics (Henderson et al. 2021), and exclusion (Goetz 2021). White supremacy culture is a threat to identity groups that have experienced othering as a result of their perceived differences as low-wealth, transgender, disabled, fat, non-English-speaking, immigrants, unemployed, and youth.

The systemic and cultural ideologies of white supremacy have manifested through violent acts (D. L. Brown 2020; Henderson et al. 2021), racial terrorism (B. Smith 2020), white vigilantism (King 2020), social exclusion (Bonds and Inwood 2016), neglected neighborhoods (Goetz 2021), and mass incarceration (Simpson, Steil, and Mehta 2020; B. Smith 2020). The overlapping and complex implications of the pervasiveness of white supremacy necessitates more focused studies and analyses that address the extent to which governance, policies, and legislative processes are impacted.

2.1.3 Critical Race Theory

It is critical for institutions, including transportation agencies, to understand the methodologies and frameworks associated with the study of systemic oppression. Such methodologies and frameworks can be used to advance equity discourse to generate equitable practices and inform an individual’s understanding of resistance to equitable practice. Critical Race Theory (CRT) is a widely debated area of study that, despite the debate, is one of the only bodies of scholarship that can inform a comprehensive understanding of equity as an operational framework. Thus, the theoretical foundations of CRT are necessary for advancing equity discourse within American institutions, including those institutions that aim to integrate equity into transportation planning and land use (Price 2010).

As an academic exploration, CRT seeks to transform the relationships between race, racism, and power to advance the liberation of racialized people (Dunbar 2008; G. Williams 2008). CRT originated in the 1980s through the work of legal scholars who were looking to develop a framework and a legal basis for challenging structural racism (Tate 1997; K. Brown and Jackson 2013). The initial applications of CRT challenged the limitations of how the legal sector considers race. The legal system often relies on finite and rigidly defined notions of racism while disregarding the fluidity and varying ways people experience racism (Martinez 2014). CRT theorists and practitioners pursue individual routes, methods, and ideas for defining racism but converge around the belief that racism is endemic (Brayboy 2021).

The theoretical foundations of CRT derive from a myriad of sociological and scientific fields which have been shown to establish impactful and responsive frameworks for ending racism and oppression (Jones 2002). For example, scholars of Ethnic Studies and oppression challenge binary thinking and advocate for atonement from people who benefit from the systems that created and uphold the impacts of slavery and other forms of oppression (Bell 1995). CRT prioritizes lived experiences by leveraging storytelling, family history, biographies, scenarios, parables, cuentos, chronicles, and narratives as key archival resources (Delgado and Stefancic 2017). With these archival resources, CRT methodologies have interrogated the practice of othering and, ultimately, have documented how the notion of ‘race’ stems from a desire to establish a ruling class (Hylton 2008).

2.1.4 Intersectionality

An intersectional framework is needed to evaluate the power dynamics in airport planning and development, based on historical context and present-day inequalities. Intersectionality is a theory derived from legal scholarship that provides insight into the ways people experience society and the ways society treats people, according to how interlocking systems of oppression show up as socially assigned combinations of identities and social markers (Crenshaw 2017). These experiences create unique modes of discrimination and privilege that are endemic in all systems and structures.

Intersectionality provides a lens to understand how an individual’s multiple socially constructed characteristics (race, gender, and ability) overlap to determine the individual’s access (or lack thereof) to power and privilege (J. D. Roberts et al. 2019). In Between Privilege and Oppression: An Intersectional Analysis of Active Transportation Experiences Among Washington, D.C., Area Youth (2019), scholars argue that within transportation the “power dynamics that flow from race, gender, class, and other systems of subjugation or privilege will generally transcend the boundaries of any given space, place or neighborhood” (J. D. Roberts et al. 2019). Individuals experience transportation-related spaces differently based on their identity in airports, on aircraft, while using transit, in transit stations, etc. Equitable planning and decision-making intend to document, highlight and prioritize the experiences of marginalized identities using an intersectional approach that considers race, gender, nationality, ability, class, employment, language, citizenship status, and educational background.

2.2 Social Constructs that Shape the Process of Othering

“The norm is something that can be applied to both a body one wishes to discipline and a population one wishes to regularize” (Foucault et al. 2003)

Othering refers to the process by which individuals or a group of people deemed “different” in a given society are isolated and/or oppressed (Chavez-Dueñas et al. 2019). The act of othering aims to isolate, exclude, alienate, and violate groups that exist outside of a white, middle- class, secular, gender-conforming, able- bodied, and documented citizen identities (Modood and Thompson 2022). Due to intersectionality, social constructions may produce oppression(s) that overlap based on one’s ability to hold multiple identities at once or different times (Coaston 2019). Furthermore, any one individual may experience a range of oppression such as poverty, racism, ageism, ableism, xenophobia, transphobia, sexism, criminalization, classism, or homophobia at “personal, interpersonal, institutional or cultural levels” (Pizaña 2017). The processes of othering and the social construction of othered identities can impact the mobility, movement, and freedom of those deemed as “other” (Leese and Wittendorp 2017).

The limits of mobility may include targeted practices that aim to maintain norms for race, sex, gender, ability, class, style, employment, language, and more (Leese and Wittendorp 2017).

Below are a few examples of othering that have been shaped by different social constructions related to race, ability, gender, language, and religion.

Othering: Latinx

“Without ceasing to be ‘the others’ in a white nation, Latinx carry one of the most heroic and unknown histories of this century: that of their color, hurt and worked until it is made hope. Hope that cafe [Brown] will be one more color in the rainbow of the races of the world, and it will no longer be the color of humiliation, of contempt, and of forgetting.” (Marcos 2004, 434)

In the United States, Latinx people have been “othered” for differences in race, ethnicity, nationality and immigration status (Chavez-Dueñas et al. 2019). The construction of race and ethnicity has evolved over time, particularly with how Latinx people are categorized. Scholar Ekeoma E. Uzogara (2019) argues that there are “dimensions” of race for Latinxs people: category-based ethnicity and feature-based race (Uzogara 2019). Category-based ethnicity is determined according to how one self-identifies as a member of the “Hispanic/Latinx” category. Feature-based racial identity occurs when others in society categorize Latinx people based on phenotypes (such as skin color) (Uzogara 2019). It is important to note the lived experiences of every Latinx person is not the same and not every Latinx person is impacted equally by racism and/or ethnocentrism (Rosa and Flores 2020). Specifically, the experiences of Afro-Latinx or indigenous Latinx who are visibly darker are the most vulnerable to othering and various forms of discrimination (Adames, Chavez-Dueñas, and Jernigan 2021).

Similar to othering, ethnocentrism refers to the process of making false assumptions about others’ ways based on an individual’s own limited experience or culture (Sue 2004; Wiarda 1981). In Healing Ethno-Racial Trauma in Latinx Immigrant Communities: Cultivating Hope, Resistance, and Action, scholars refer to “the conundrum of race and ethnicity” which allows Latinx people to be victims of both racism and ethnocentrism (Chavez-Dueñas et al. 2019). The authors support their argument by naming instances throughout United States history where Latinx people have been victim to “ethno-racial” discrimination (Chavez-Dueñas et al. 2019; Baker et al. 2022) such as the lynchings of Mexicans by white mobs (Gómez 2018; Binford and Churchhill 2009) and segregation of Latinxs during the Jim Crow Era (Chavez-Dueñas et al. 2019). The rise of nationalism in the United States (Devadoss 2020) and aggressive enforcement of immigration policies (Chavez-Dueñas et al. 2019; McNamara 2020) are instances of ethnocentrism as a result of othering towards Latinx people (Kagedan 2020).

Othering: Language

Linguistic othering is the process through which people are socially, culturally, and politically marginalized due to their non-English or extra-English language proficiency. There are reports of people who are non-English-speaking or English-speaking with an accent being targeted or harassed within the United States (Lippi-Green 2011). The alienation of those with foreign or non-American accents being scrutinized, teased or discriminated against is also an example of othering (Devadoss 2020). Early manifestations of linguistic othering include the suppression of hundreds of indigenous languages and the prohibition on African languages that were enforced during the conquest that led to the

incorporation of the United States and during the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. Over time, English-only naturalization policies and education policies further reinforced linguistic hierarchies. For example, the Naturalization Act of 1790 (which initially required immigrants to be “free white persons” of “good character” and speak an oath in support of the U.S. Constitution) was first amended in 1906 to add English proficiency as a citizenship requirement.

Linguistic othering yields detrimental outcomes that erode quality of life. People who speak languages other than English, people who have foreign accents, and people who have dialects that are often associated with racialized identities face discrimination in the job market, with limited access to well-paying positions and career advancement opportunities. This discrimination may be overt or subtle, affecting hiring decisions and promotions. Additionally, many essential services, such as healthcare, legal representation, and government assistance, are predominantly available in English. For people who speak languages other than English, this results in limited access to vital resources and information, contributing to disparities in healthcare outcomes and legal protection.

Othering: Religious Attire

Othering associated with religious attire refers to the social, cultural, and political marginalization experienced by individuals due to their religious clothing, such as hijabs, turbans, kippahs, or religious robes. The practice of people wearing head covers and veils for religious purposes is an integral part of multiple religions, faiths, and cultures (Chico 2013). Particularly, in a post 9/11 context, there have been several documented cases of harassment or intimidation towards people wearing religious headwear like hijabs, Niqaby, or burqas (Chen 2010; Cashin 2010). More specifically, women who wear headwear are stereotyped as “oppressed” under their religious influence (Aziz 2012). Common examples of othering based on religious attire include the following:

- Muslim women who wear the hijab often face Islamophobia, including verbal abuse, physical attacks, and employment discrimination. The hijab is sometimes misperceived as a symbol of oppression rather than an expression of faith.

- Sikh men who wear turbans and maintain beards as expressions of their faith have faced hate crimes and discrimination, often being mistaken for Muslim individuals.

- Anti-Semitic incidents sometimes target people wearing kippahs, who are singled out due to their visible religious identity.

The social impacts of othering and discrimination based on religious attire include psychological distress such as anxiety, reduced sense of belonging, and post-traumatic stress. Those experiencing racism as a result of their religious attire may also resort to or be subject to forms of social isolation that could motivate hate crimes while also exacerbating psychological impacts. Finally, by way of discrimination based on religious attire, people are often subject to education and employment discrimination.

2.3 Legacies of Group-Based Othering Within Aviation

Sections 2.3.1 through 2.3.7 include contemporary examples of concepts introduced in Section 2.1 and 2.2. These sections are not meant as a comprehensive account of othering across the history of aviation but intend to provide relevant present-day examples for practitioners to consider.

2.3.1 Profiling and Harassment of Religious Groups

Trauma-inducing events like acts of terrorism have been leveraged to justify the process of racialization (Gotanda 2011). For example, following the coordinated suicide attacks that took place in the United States on September 11, 2001 (also known as 9/11), anti-Muslim sentiment and hate crimes against people who were perceived to be Muslim increased in the United States. Scholars argue that government officials used the post 9/11 rationale to legitimize racial profiling and discrimination of those who appeared to not assimilate into western customs and social norms (Blackwood 2015; Blackwood, Hopkins, and Reicher 2013). Because the attacks were carried out by people who identified as Muslim, racial profiling of Muslims, particularly those of Middle Eastern and South Asian descent, became commonplace in mainstream media and vigilante responses to 9/11.

As Islam is a religion and is not characterized as a race in any standardized social frameworks or census processes, the widespread response to Muslims after 9/11 is an example of othering that shows how the social construction of race can be inconsistent and can contradict widely accepted notions of race altogether. Processes of othering are not about establishing concrete definitions of groups of people, rather these processes intend to create systemic structures of “dominant groups” and “oppressed groups,” strengthening the status quo of cultural hierarchy (Cainkar 2009).

Several scholars have studied the racialization of religion more broadly and find Hinduism, Sikhism, and Judaism are also commonly the subjects of racialized othering (Joshi 2016). The racialization of religion is especially apparent in the context of airports as people who have been racialized by way of their religious beliefs encounter disproportionately extensive security screening and scrutiny among other passengers (Selod 2019).

Figure 5 displays a photograph of protesters inside a terminal at Chicago O’Hare International Airport on January 28, 2017; one day after President Trump signed an Executive Order (E.O.) that banned travel to the United States for 90 days from predominantly Muslim countries. In the photograph, protesters hold signs indicating support for the refugees and immigrants.

Source: Photo courtesy of Amy Guth, https://www.flickr.com/photos/amyguth/32466287011/in/photostream

2.3.2 Profiling and Harassment of Gender Groups

Airport travel for transgender and nonconforming people can be a hostile experience, particularly when there is a difference between the gender marked on one’s travel documents and one’s perceived gender presentation while passing through airport security (Abini 2014). Understanding lived transportation experiences of LGBTQIA+ people is of critical importance for those responsible for ensuring equitable outcomes in aviation. Compounding factors in all transportation contexts for queer people and other people experiencing oppression can be explained through the theory of intersectionality discussed in Section 2.1.4.

Despite limited peer-reviewed literature depicting the unique experiences of queer people interacting with airports, there are many blogs, websites, and vlogs which share community voices, detail challenges, and offer strategies for LGBTQIA+ people to avoid criminalization and harassment while traveling. For example, a travel research website called Asher & Lyric is dedicated to “[helping] hundreds of thousands of individuals every month stay safe, healthy, and happy at home and while traveling.” The site features research-based safety rankings and travel advice for LGBTQIA+ people who are considering global travel destinations (Fergusson and Fergusson 2022). In a vlog, YouTuber Gigi Gorgeous shared her experience being detained for being transgender when she traveled to Dubai (Loren 2016; Petit 2016).

In addition to safety concerns, other challenges for LGBTQIA+ people navigating within the aviation industry include documentation, security screening, uniforms, and bathrooms.

Documentation/Security Screening

In 2015, Dana Zzyym, an intersex and nonbinary individual, brought a lawsuit against the U.S. State Department for the inability to be issued a passport that reflects their gender identity (Lambda Legal 2021). In April 2022, the State Department added “X” as a third gender identification option on passport application forms to represent “unspecified or another gender identity” (Joe Hernandez 2022). As a result, as of 2022, both airlines and Transportation Security Administration (TSA) are working to update their systems to allow travelers to mark their gender as “X” (Pickett 2022).

Additionally, TSA body scanners and pat-downs may flag transgender people’s bodies and extensions of their bodies, such as prosthetics, as anomalies, resulting in additional screening and questioning. This is because TSA body scanners are based on two models: one cisgender man and one cisgender female, so if a person’s body does not match one of the models it is automatically flagged as an anomaly (Shadel 2021). Advocates have documented and communicated requests to the TSA for updated security screening procedures and personnel training to prevent discrimination and harassment (Lambda Legal 2015). In the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, representing responses from over 27,000 respondents, over 40 percent of respondents who reported going through airport security in the previous year (53 percent of total respondents) experienced an issue while going through security such as use of the wrong pronouns, pat-downs, questions about name and identity, and questions about body parts (James et al. 2016).

Uniforms

Gender-specific appearance standards and uniforms are common in the aviation industry including, but not limited to, positions such as security agents, flight attendants, and pilots. Gendered appearance standards and uniforms have been challenged by gender nonconforming people. A YouTube video details, Ashley Yang’s experience working for the TSA at Los Angeles International Airport as a transgender woman. She was “told she would have to work as a man and comply with the male dress code,” cut her hair, use the men’s bathroom, and pat down male passengers (itlmedia 2011; Leff 2011).

Yang ultimately was fired, challenged her employer in court, and entered into a settlement agreement. In another case, advocates argued on behalf of a nonbinary airline employee that Alaska Airline’s uniform policies represent discrimination based on gender identity, self-image, appearance, behavior, expression and discrimination based on sex (American Civil Liberties Union 2021). In 2021 and 2022, multiple airlines, including Alaska Airlines, announced updated gender identity policies and non-gendered uniform options for employees (Singh 2021; Kunzler 2022; Amati 2022).

Bathrooms

Another challenge experienced by transgender and nonconforming people when interacting in the airport environment is the existence and use of gendered bathrooms. Close to 60 percent of respondents to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey reported that they sometimes or always avoid using public restrooms to avoid confrontations or other issues. Twenty-six percent of respondents reported experiencing denial of access to restrooms, questioning of their presence in a restroom, and/or experiencing verbal harassment, physical attacks, sexual assault when in a restroom. Some airports undergoing bathroom upgrades and redevelopment have recently focused on adding or identifying all-gender inclusive bathrooms to create safe spaces for all passengers (James et al. 2016).

Figure 6 displays a photograph of a wall-mounted bathroom sign at an airport. The text indicates that persons who self-identify as a woman are welcome, which is also communicated in braille. Symbols also indicate facilities are appropriate for wheelchair users and infants.

2.3.3 Sexual Harassment and Assault

Airports exist within an aviation system; airports and airlines influence and affect various components of the passenger experience. Airports may benefit from improving awareness of and considering experiences outside of their immediate jurisdiction to gain a more holistic view of discrimination, sexual misconduct, and harassment or assault that may occur throughout the passenger experience and within the aviation industry workforce. Sexual harassment, assault, and misconduct on aircraft affects both flight attendants and passengers. As industry partners, airports and airlines have a shared interest in preventing this behavior.

Source: Photo courtesy of Gala Korniyenko, The Ohio State University, Public Domain

Flight attendants have endured a history of sexualization and discrimination in the male dominated aviation industry. As recently as the 1970s, flight attendants endured weigh-ins and weight restrictions, strict grooming, and uniform requirements, “no marriage” rules, and early retirement policies. Although airline policies have been updated since, legacies of inequity remain (Regan and Thompson 2018). In 2018, the Association of Flight Attendants-CWA released a survey of over 3,500 flight attendants representing 29 U.S. airlines which documents how pervasive harassment remains in the industry. Almost 70 percent of respondents have experienced sexual harassment in their career as a flight

attendant. In the year prior to the survey, 35 percent of respondents reported verbal sexual harassment from passengers and 18 percent experienced physical sexual harassment from passengers (Association of Flight Attendants 2018).

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Reauthorization Act of 2018 included multiple sections that address sexual misconduct on aircraft. Section 338 addresses that airlines should have policies and procedures related to sexual misconduct. Section 339 gives the FAA the authority to assess a $35,000 civil penalty to individuals for sexually assaulting or threatening to sexually assault any other individual on the aircraft. Section 339B requires U.S. Department of Justice to establish a process for reporting inflight sexual misconduct and abuse to law enforcement (U.S. Department of Transportation, National InFlight Sexual Misconduct Task Force 2020).

The FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 also established the National In-Flight Sexual Misconduct Task Force (Section 339A) which was tasked with researching and publishing a report to compile first-hand accounts of victims of misconduct and assault, review airline practices and policies, and establish recommendations for airlines on training, reporting, and data collection related to sexual misconduct and assault on aircraft. Victims recount that reporting incidents to flight attendants is difficult as the aircraft cabin is often small and there is a lack of privacy. The report recommends that aircraft crew contact law enforcement if misconduct occurs and requests that all allegations be forwarded to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) (U.S. Department of Transportation, National In-Flight Sexual Misconduct Task Force 2020). The FBI encourages the flying public to stay aware of their surroundings and report any sexual assault to flight attendants. The FBI employs airport liaison agents in each of its 56 field offices that respond to onboard crime (FBI Los Angeles 2022).

2.3.4 De-Prioritization of Services for People Using Ambulatory Devices

Airports and aircraft are challenging spaces for people with disabilities to navigate due to airport and aircraft space configurations and constraints. Passengers who use wheelchairs and other ambulatory devices often experience a variety of challenges on their travel journeys. For example, single-aisle aircraft are not required to have a wheelchair accessible bathroom onboard. Often, passengers who rely on wheelchairs do not drink or eat for hours before flying for fear of having to use the restroom (A. Morris and McIntyre 2022). Within the airport itself, Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) compatible bathrooms are required but some people with disabilities require equipment beyond a standard toilet such as a hoist, shower, and adult changing table. Airports are working toward improving accessible and companion care restrooms to offer more equipment and improve the travel experience for people with disabilities and their caregivers (J. Morris 2022).

Personal wheelchairs are too wide for aircraft aisles, so people who use wheelchairs are transferred by airline staff to an airline “aisle chair” to bring them to their seat. Transfers are often uncomfortable and can result in injuries if they go awry. The passenger’s personal wheelchair is then transferred to the cargo hold underneath the aircraft where it many end up damaged in some way (J. Morris 2016). Senator Tammy Duckworth, a double amputee and wheelchair user recounts that, “When an airline damages a wheelchair, it is more than a simple inconvenience—it’s a complete loss of mobility and independence. It was the equivalent of taking my legs away from me again.” She fought for an amendment to the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 that requires monthly reporting on airport mishandling of wheelchairs and scooters through Air Travel Consumer Reports. The reports show that 10,548 wheelchairs or scooters were reported as lost, damaged, delayed or stolen in 2019 alone, which represents the first full year of reported data (H. Sampson 2021).

Upon arrival at their destination, people who use wheelchairs are the last to deplane. Sometimes, if their personal wheelchairs are delayed delivery to the gate, they must sit in the aisle chair for extended periods of time, causing discomfort or sores. Other times, airline staff transfer these individuals to their personal wheelchair or mobility device in the boarding area, in front of other waiting passengers at the gate, the lack of privacy exposing the individual to stares and discomfort. In a New York Times article documenting a typical flight for Charles Brown, a person who relies on a wheelchair and frequent flyer, reports, “It’s frustrating…I’m not going to say ‘embarrassing’ anymore because I’m just over that” (A. Morris and McIntyre 2022).

Air travel would be significantly more accessible for wheelchair users if they could remain in their personal wheelchair or mobility device instead of transferring to an aircraft seat. All other forms of transportation allow for this type of service, but no wheelchair securement systems exist for aircraft. Aircraft have limited doorway and interior space, weight restrictions, and must meet FAA crashworthiness and safety requirements. The National Academy of Science (NAS) published Technical Feasibility of a Wheelchair Securement Concept for Airline Travel, which suggests that preliminarily there do not appear to be unsurmountable design or engineering challenges, but substantial effort would be necessary to demonstrate the change and additional safety assessments are warranted (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2021a).

In 2022, the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) published the Airline Passengers with Disabilities Bill of Rights outlining the fundamental rights of passengers with disabilities and the aviation industry’s responsibility for upholding them (U.S. Department of Transportation 2022c). The USDOT also adopted Disability Policy Priorities in 2022 for enabling safe and accessible air travel. The priorities intend to achieve four goals related to addressing the challenges identified above:

- Allow passengers to stay in their personal wheelchairs on aircraft.

- Decrease number of passengers whose wheelchairs are damaged during air travel and are injured in transfers to/from aircraft.

- Ensure passengers in wheelchairs can access lavatories on aircraft.

- Decrease frequency of incidents where passengers’ civil rights are violated and increase in equal access to quality air transportation service for persons with disabilities (U.S. Department of Transportation 2022d).

ACRP has published multiple guidance resources related to improving the passenger experience for people with disabilities and aging, or mobility challenged adults. Three key publications include ACRP Report 210: Innovative Solutions to Facilitate Accessibility for Airport Travelers with Disabilities (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2020), ACRP Report 177: Enhancing Airport Wayfinding for Aging Travelers and Persons with Disabilities (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2017), and ACRP Research Report 231: Evaluating the Traveler’s Perspective to Improve the Airport Customer Experience (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2021b).

Figure 7 displays a photograph of a ceiling-mounted airport wayfinding sign that indicates the location of facilities to care for nursing infants and service animals.

Source: Photo courtesy of Gala Korniyenko, The Ohio State University, Public Domain

2.3.5 Challenges Accommodating non-English Speakers and Wayfinding

People who speak languages other than English and people with limited English proficiency often experience accessibility and wayfinding challenges in airports and on aircraft. According to a survey conducted for ACRP Research Report 161, “one in four international passengers can read only a little English, or none at all.” Many U.S. airports only provide wayfinding signage in English. Customer service representatives and information desks should offer resources or language translation services for limited or non-English-speaking customers. Security checkpoints and U.S. Customs and Border Protection should consider disseminating information in multiple languages or having internet enabled devices available to help translate. Visual communication such as pairing symbols with text on signage assists with comprehension. Airports could also determine the most commonly spoken foreign languages at their airports and their airlines travel destinations to ensure resources are available for those passengers (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016).

Members of Congress recognize these challenges for the traveling public and are working on passage of Senate Bill 3296, TSA Reaching Across Nationalities, Societies, and Languages to Advance Traveler Education Act, which was introduced by Senators Jacky Rosen (D-NV) and John Cornyn (R-TX). The bill intends to “simplify air travel for non-English speakers, international travelers, and those with visual and/or hearing impairments by ensuring TSA signage and materials at airports are available in more languages and in additional forms, which will support travel and tourism in and to the United States” (Office of Jacky Rosen, U.S. Senator for Nevada 2022)

2.3.6 Practices of Exclusion and Tokenism in the Workforce

Due to early and ongoing racial and gender-based discrimination, the aviation industry continues to be coded as a White and cisgendered male industry, prone to the exclusion and tokenism of marginalized people. As reported in the conference proceedings for the ACRP Insight Event Systemic Inequality in the Airport Industry: Exploring the Racial Divide, a main theme in the dialogue was the “recurrence of

personal testimonials that described strategies and decisions that minority-identifying individuals had to address as they navigated the workplace” (McNair 2023). The event panelists frequently referred to their own experiences as the “first” and/or the “only” marginalized identity in an airport workplace. The corresponding emotional labor required to navigate an “othered” experience in the workforce and the pressures to assimilate were regarded as harmful and disruptive to their professional pursuits. In an effort to document the lack of diversity across airport workers, ACRP funded close to $800,000 in 2023 toward research that investigates representation of women and minorities in airport employee populations under ACRP Project 06-09: Equitable Workforce Outcomes: A Study of Women and Minority Representation at Airports. This project is anticipated for publication in spring of 2025.

Although not specific to airports, airline pilots represent a commonly recognized career path within the aviation industry. Pilots are among the least diverse labor pools in the United States. Based on 2020 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data, 94 percent of aircraft pilots and flight engineers in the U.S. identify as white (Thompson 2021). This statistic results from practices of exclusion based on gender and race throughout the history of aviation in the U.S.

Despite the participation of Black people and women as pilots in experimental flight and in aerial performances of the 1910s and 1920s, these groups faced overt discrimination as the aviation industry professionalized. Within the military, Black people were excluded from becoming pilots in the United States until World War II. The Tuskegee Airmen were the first Black fighter pilots in U.S. history and the military remained racially segregated until 1948 (Thompson 2021). Exclusionary and discriminatory practices also reigned in commercial and private airlines until 1964. Marlon DeWitt Green was a retired U.S. Air Force pilot with over 3,000 hours of flight time who was rejected from employment by Continental Airlines because he was racialized as Black. Green challenged Continental Airlines’ discriminatory practices in the legal system, ultimately taking his case up to the U.S. Supreme Court.

“…The only reason he got the flight test with Continental was the fact that he didn’t check the race box on the application form and he didn’t enclose a picture, both of which were required at the time. And so Continental looked at his qualifications, said, ‘Ah, here’s a guy who knows how to fly. Let’s bring him into Denver and give him a flight test.’ And he gets here and he’s, ah, the wrong color. And the fact is that they brought him in so they might as well give him the flight test and they still rejected him.” (Warner 2017)

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously in Green’s favor. The legal win paved the way for David Harris to become the first Black pilot to be hired by a commercial passenger airline in 1964 and Green began flying for Continental Airlines in 1965 (Fikes 2017). Yet, being “the only” remains a common lived experience for racialized people and people with disabilities in the aviation industry. Carole Hopson is a first officer for United Airlines and was once the only Black female pilot in her class. She plans to diversify the industry and increase Black representation, specifically focusing on opportunities and decreasing barriers to entry for Black women in aviation. She runs a nonprofit, the Jet Black Foundation that is focused on enrolling 100 women of color in flight school by 2035 (Brabham 2022).

2.3.7 Monuments of White Supremacy

Airport namesakes can serve as legacies of white supremacy. For example, Benjamin Franklin Stapleton was a prominent member of the Ku Klux Klan and served as mayor of Denver, Colorado from 1923 to 1931 and from 1935 to 1947. Stapleton was instrumental in appointing and facilitating KKK members into city leadership positions during his tenure. Stapleton was also known for his commitment to major public works projects, including the Denver Municipal Airport, which opened in 1929. The airport was renamed Stapleton Airfield in honor of the mayor in 1944, then renamed again (Stapleton International Airport) in 1964 when the airport expanded commercial service offerings.

Stapleton International Airport was eventually replaced by the newly constructed Denver International Airport in 1995 on land annexed from nearby Adams County. After Stapleton airport closed, the Stapleton land area retained the neighborhood name “Stapleton” and was subdivided and zoned to be used for various purposes, including residential neighborhoods. Multiple community groups, such as Rename for All, formed to rename the neighborhood due to concerns over Stapleton’s legacy. After years of attempts, the George Floyd protests in 2020 reinvigorated community efforts to remove Stapleton’s name from municipal place markers. In summer 2020, the community voted to rename itself as “Central Park” (Meltzer 2017; Tabachnik 2020; Swanson 2021).